Abstract

There is a need for new, targeted smoking cessation interventions for smokers living with HIV. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model has been applied effectively to HIV-related health behaviors and was used in this qualitative study to elicit factors that could lead to the development of innovative and successful cessation interventions for this population. Twenty individuals who smoked from two clinics providing care to people living with HIV participated in open-ended interviews, responding to questions covering the domains of the IMB model, as applied to smokers living with HIV. Participants were enrolled from a larger survey cohort to recruit into groups based on the impact of HIV diagnosis on smoking as well as attempting to enroll a mix of demographics characteristics. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded and thematically analyzed using a grounded theory qualitative approach. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was reached. Major themes included: Presence of knowledge deficits regarding HIV-specific health risks of smoking; use of smoking for emotional regulation, where many reported close contacts who smoke and concern with the effect of cessation on their social networks; Use of smoking cessation aids or a telephone-based wellness intervention were acceptable to most. Providing HIV-specific information in cessation advice is of the utmost importance for clinicians caring for smokers living with HIV, as this theme was noted consistently as a potential motivator to quit. Innovative and effective interventions must account for the social aspect of smoking and address other methods of emotional regulation in this population.

Keywords: smoking, tobacco, HIV, AIDS, cessation, behavior

Introduction

Over 40% of people living with HIV in the United States are smokers – over twice the rate in the general population.(Mdodo et al., 2015; Jamal et al., 2016) Negative health consequences of smoking are amplified in the setting of HIV infection.(Reddy et al., 2016; Shirley, Kaner, & Glesby, 2013; Lifson et al., 2010) Less attention has been paid to smoking cessation in this population because of the increased mortality related to HIV/AIDS but improvements in HIV treatment have allowed the focus of care to move towards other chronic conditions influenced by smoking including cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer.(Aberg et al., 2004) In addition to reducing the risk to health related to these conditions, smoking cessation is now known to extend life expectancy and improve quality of life in people living with HIV.(Reddy et al., 2016; Vidrine, Arduino, & Gritz, 2007) However, smokers living with HIV (SLWH) are less likely to receive smoking assessment and intervention than HIV-negative smokers seen in general medical clinics.(Crothers et al., 2007) Many SLWH underestimate the dangers of smoking and may have lower motivation to quit.(Mamary, Bahrs, & Martinez, 2002; Reynolds, Neidig, & Wewers, 2004) Greater understanding of the information, motivation and behavioral skills deficits and strengths related to smoking cessation is needed in order to develop new interventions.

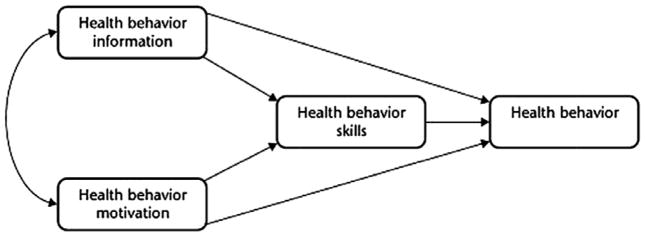

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model posits that the extent to which individuals are well-informed, motivated to act, and have the behavioral skills required for effective action dictates whether they are likely to initiate and maintain health-promoting behaviors and to experience positive health outcomes (Figure 1).(J D Fisher & Fisher, 1992) The IMB model has been previously applied to HIV treatment adherence and other health behaviors.(Jeffrey D Fisher et al., 2011; Jeffrey D Fisher, Cornman, Norton, & Fisher, 2006; Moadel et al., 2012; Rivet Amico, 2011)

Figure 1.

Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model. Note. Modified from original figure from Psychological Bulletin, 111 (3) (1992), pp. 455–474 by J.D. Fisher and W.A. Fisher Copyright 1992 by APA Publishing. Reprinted with permission.

According to the model, information is a fundamental determinant of health behavior when the information is directly relevant to health behavior performance and can be easily enacted within the social context.(Fisher W, Fisher J, 2003) The model also suggests that both personal and social motivation will influence smoking behavior. Both perceived self-efficacy and objective abilities are included in the behavioral skills component of the model. For complex behaviors like smoking, information and motivation work primarily through behavioral skills to impact health promotion behavior. There are multiple behavioral skills related to smoking including securing social support, managing withdrawal symptoms, self-monitoring, self-reinforcement, coping and emotion-regulation skills, managing cessation treatment side effects, using cessation medications as recommended, and increasing self-efficacy for cessation.(2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff, 2008) It is unknown whether these types of cessation-related skills have a similar influence in SLWH as in other populations. In this formative study, we aimed to describe how the IMB model can be applied to smoking behavior among SLWH and explore how it could be used to develop targeted cessation interventions.

Methods

The study was conducted in 2010 at two clinics with a mix of urban and rural patients in Wisconsin. Eligible individuals were those with known HIV infection with pre-existing clinic appointments, current smokers (>1 cigarette/day), able to communicate in English, age ≥18 years, with the ability to provide informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin - Madison Institutional Review Board.

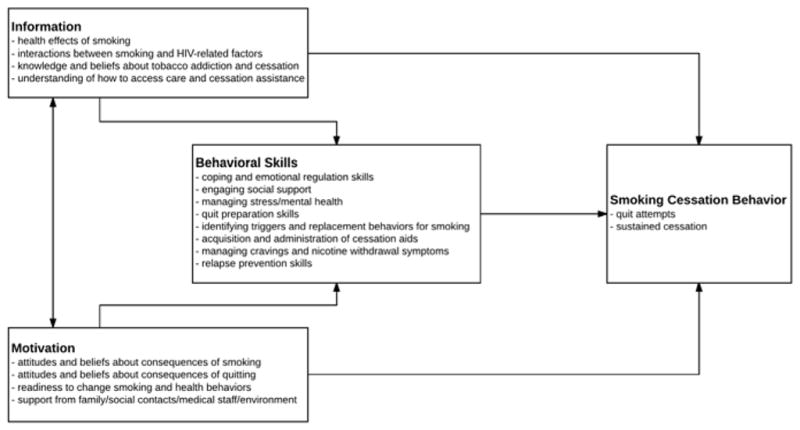

A larger study in these clinics recruited 80 individuals by convenience sampling to complete a survey about factors associated with acceptance of a quit line referral (results not shown). The survey included assessment of knowledge related to the health effects of smoking and HIV, self-efficacy for cessation and behavioral skills related to cessation. Additional information gathered for the larger study included smoking history, nicotine dependence (Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence), demographic characteristics, medical history including most recent HIV viral load, CD4 counts, and antiretroviral therapy, and completed screening assessments for depression (PHQ-8(Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001)) and alcohol use (AUDIT-C(Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998)). Participants for this qualitative study were purposively selected from the larger cohort based on response to how HIV diagnosis affected smoking to create three groups: those who increased, decreased, or did not change smoking exposure in response to HIV diagnosis. Selection attempted to allow representative and diverse demographic characteristics based on age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Data saturation was achieved before the last interview, as determined by staff when further interviews did not elicit new categories or themes. Potential participants were informed that the purpose was not to get them to quit. An experienced research nurse audio recorded interviews with participant knowledge and consent. Interviews lasted approximately 45 minutes. Tapes were identified by a unique study ID, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed to ensure accuracy. The interviewer exerted minimal control over the order and structure of the session to elicit information that was relevant from the participant perspective. The guide covered domains of the IMB model, as applied to SLWH (Table 1, Figure 2) and answers to 35 questions were elicited and recorded, although because of the open-ended nature of the interview, interviewers generally did not have to explicitly ask each question. Participants received a small stipend, mailed to them the day the interview was completed.

Table 1.

Interview Guide Topics

| Smoking-Related IMB Domains | Discussion Topics | Interview Guide Questions |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Sources of Information | Sources of smoking related and HIV-specific smoking related information | Has anyone in your HIV doctor’s clinic given you information about smoking or talked to you about quitting smoking? |

| Has anyone in other medical settings given you information about smoking or talked to you about quitting smoking? | ||

Has anyone at AIDS Network*, ARCW* or elsewhere in the community given you information about smoking or talked to you about quitting smoking?

| ||

| Unmet informational needs | Thinking about smoking and HIV, what would you like to find out more about? | |

| Thinking about treatments to help stop smoking, what would you like to find out more about? | ||

|

| ||

| HIV-Specific Smoking Knowledge | Understanding of possible health risks to HIV-positive people associated with smoking | How do you think smoking affects the health of people with HIV? |

| Understanding of smoking risks in the context of antiretroviral treatment | What have you heard about smoking when you take HIV medications? | |

|

| ||

| Risk Probability Knowledge | Understanding of relative risk of smoking specific to HIV. | How do the risks of smoking differ when someone does or doesn’t have HIV? |

|

| ||

| Heuristics about Smoking Risks and Importance of Quitting | Experiences that increase/decrease perception of risks of smoking | How do you know whether or not smoking is affecting your personal health? |

| Are there times when you feel like smoking is better for you than not smoking? | ||

| Experiences that increase/decrease desire to change smoking behavior | Are there situations related to your HIV that make you want to cut back on your smoking? | |

| Are there situations related to your HIV that make you want to quit smoking? | ||

| Effect of having HIV on smoking | Are there situations related to your HIV that make you want to continue smoking? | |

| How has having HIV affected your smoking? | ||

|

| ||

| Personal Motivation | Motivational barriers and facilitators to cessation | What are the things you like about smoking? |

| What are the things you don’t like about smoking? | ||

| How does the experience of having HIV make it easier or harder for people to think about quitting smoking? | ||

| What would be different in your life if you quit smoking? | ||

| What concerns do you have related to smoking at this time? | ||

|

| ||

| Social Motivation | Perceived positive and negative social support for quitting smoking | Has anyone suggested that you should cut back or quit smoking? Who? |

| Who would be a support if you decided to quit smoking? | ||

| Who would make it more difficult if you decided to quit smoking? | ||

| Social norms for smoking | What do the people who are important to you think about whether you should smoke (probe about family, friends, others)? Has that changed since you were diagnosed with HIV? | |

| What would you guess as the percentage of people who have HIV who also smoke? | ||

|

| ||

| Smoking Cessation Strategies | Context of cessation strategies that have and have not worked | Have you tried to quit smoking after you were diagnosed with HIV? Had you tried to quit before you were diagnosed? (probe for similarities and differences in these experiences, if appropriate) |

| Can you tell me a little about the last time you quit smoking? | ||

| Have you ever used nicotine patches or considered using them? | ||

| Do you think you might be willing to try nicotine patches in the future, if they were available for free? | ||

| Have you ever used a tobacco telephone quit line or received counseling on how to quit smoking? | ||

| Do you think you might be willing to try that in the future, if it were available for free? | ||

| Skills-related barriers to cessation | What do you think would get in the way of your quitting smoking or staying quit? | |

| Strategies to reduce barriers | What do you think would make it easier for you to quit/stay quit? | |

|

| ||

| Self-Efficacy for Cessation | Confidence in skills for quitting smoking | Do you think it would be easier or more difficult for someone with HIV to quit smoking (compared to someone who doesn’t have HIV)? |

| How confident are you that you could quit smoking if you wanted to? | ||

|

| ||

| Intervention Acceptability | Acceptability of program that includes smoking cessation for HIV+ smokers | Would you consider participating in a telephone program about how to live well with HIV, if smoking was one of the topics covered? |

Regional AIDS Service Organization (ASO)

Figure 2.

Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model for Smoking Cessation

QSR N-Vivo 8 software (QSR International, 2008) was used for data management and analyses. Two members of the analytic team formally content-coded all transcripts. Data were analyzed using grounded theory strategies to identify relevant themes.(Strauss A, 1994) New categories and themes that did not appear to fit the conceptual framework were discussed by the coders and modifications made accordingly. Relations and associations among categories were interpreted and decision trails documented. Thematic categories were refined, merged, or subdivided. This process continued iteratively until thematic saturation was achieved, at which time a codebook was developed to include themes, illustrative texts, and node addresses. Half of transcripts were double-coded for comparison. Inter-rater agreement was 87%.

Results

Twenty participants were recruited, including 16 men and 4 women (Table 2). The average age was 42, 80% of participants were of non-Hispanic white race, 75% were taking antiretroviral therapy, 50% smoked 11–20 cigarettes per day, and the average years of smoking was 22. These characteristics were similar to the larger survey study. Main themes by IMB domain are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics

| Sample Population N = 20 |

||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

| Age, years | ||

|

| ||

| 20 – 29 | 2 (10) | |

| 30 – 39 | 6 (30) | |

| 40 – 49 | 7 (35) | |

| ≥ 50 | 5 (25) | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

|

| ||

| Male | 16 (80) | |

| Female | 4 (20) | |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

|

| ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 16 (80) | |

| African American, Non-Hispanic | 4 (20) | |

|

| ||

| Education Level | ||

|

| ||

| Less than HS grad, ≤11 years | 3 (15) | |

| HS grad, = 12 years | 6 (30) | |

| Some College = 13 – 15 years | 7 (35) | |

| College grad or higher ≥ 16 years | 4 (20) | |

|

| ||

| Number of cigarettes/day | ||

|

| ||

| Less than or equal to 10 | 7 (35) | |

| 11 – 20 | 10 (50) | |

| 21 – 30 | 2 (10) | |

| Greater than or equal to 30 | 1 (5) | |

|

| ||

| Currently on ART | ||

|

| ||

| Yes | 15 (75) | |

| No | 5 (25) | |

|

|

||

| M (SD) | Range | |

|

|

||

| Age, years | 42 (10.38) | 22 – 57 |

|

| ||

| Number of years smoked | 22.45 (10.19) | 5 – 40 |

|

| ||

| Quit Months | 17.6 (37.16) | 0 – 144 |

|

| ||

| Viral Load | 35004 (70354.40) | 0 – 219,000 |

|

| ||

| CD4 count | 564 (454.21) | 19 – 1,999 |

HS = High School; ART = Antiretroviral Therapy.

Table 3.

Main Themes by Smoking-Related IMB Domains

| Smoking-Related IMB Domains | Main Themes |

|---|---|

| Sources of Information |

|

| HIV-Specific Smoking Knowledge |

|

| Risk Probability Knowledge |

|

| Heuristics about Smoking Risks and Importance of Quitting |

|

| Personal Motivation |

|

| Social Motivation |

|

| Smoking Cessation Strategies |

|

| Self-Efficacy for Cessation |

|

| Intervention Acceptability |

|

Information

Participants estimated the percent of people with HIV who smoke: one said 15%; 3 responded 30–40%; 6 reported 50–60%; 4 said 60–80%; 1 stated 90%. Most participants (17/20, 85%) said smoking was discussed at their HIV doctor’s office but 80% also commented negatively on this: “they just ask, they don’t try to intervene” “they don’t offer HIV specific information” “they just push drugs to quit.” One individual viewed the interactions positively: “They ask if I’m still smoking, if I need help, if they can provide anything.” Attendance at AIDS Service organizations (ASOs) was low, but of those who did attend, most (7/8, 88%) commented that smoking was not mentioned there: “they’re afraid of driving you away if they ask” “they smoke too.” Smoking was also mentioned at dentist and specialist offices. Other sources of information included coffee houses, HIV− focused magazines and websites, and an alternative healer.

Thirteen participants (65%) stated they had no specific questions about smoking and HIV. Others asked how to find HIV and smoking-specific information, how the effects of smoking are different in those who are HIV+, how smoking affects HIV treatments, and whether smoking impacts lipodystrophy. Three participants asked about the effects of smoking on other health conditions including breast cancer, sinus infections, and “pre-diabetes”. Six articulated questions concerning cessation treatments.

Seven participants believed the effects of smoking with HIV had something to do with a weakened immune system. Six indicated there was no difference in risk: “I think it affects everybody the same … If it’s going to do damage, it’s going to do damage.” Four said they did not know, while one commented that there may be an increase in respiratory problems and another cited cardiac issues.

When queried about the effect of smoking when taking HIV medications, 70% responded that they had not heard anything or did not know anything about this. One mentioned that the medications increased his appetite, so he felt he needed to smoke to maintain his weight. Another felt “Guilt … taking pills to enhance your life … and a substance which can reduce your health...”

Of the 20 participants, nine felt that the initial diagnosis of HIV did not affect their smoking, although two of those went on to describe an indirect effect. “it caused me to drink more … and probably smoke with that.” Three participants described an increase in smoking: “I smoked a lot more from the stress.” Three commented that ongoing stress related to HIV keeps them from quitting, referencing financial stressors, boredom due to being unable to work, and stigma of being HIV-positive. One participant said he cut back initially, “… because I thought maybe the smoking would get you more sick.”, but soon relapsed and one commented that HIV made him think about quitting. Seven individuals reported awareness that their health was affected by smoking when they noticed shortness of breath or coughing, while six others reported they did not see any ill effects. “I think I’m probably in better shape than people that don’t smoke.”

Seven participants reported that having certain illnesses made them want to quit, including thrush, pneumonia, emphysema, and recurrence of breast cancer. Four said there were no situations that made them want to quit. Two were bothered by seeing other smokers cough frequently and two said thinking about the long term effects influenced thoughts of quitting. Frequent doctor appointments made one participant cut back because smoking is banned there.

Regarding reasons to continue smoking, 10 references were made to the emotional regulating effects of smoking, including depression, anxiety, “daily stressors”, stress of chronic illness, and stigma—”there are judgments about your lifestyle that led you to having this.” Nine said there were no situations that made them want to continue smoking, providing explanations such as “it’s just a chemical dependency,” “I just enjoy smoking,” or fear of weight gain.

Motivation

Seventeen individuals mentioned mood regulating effects as motivation to continue smoking. Four continued for social reasons: “I know a whole bunch of smokers. I guess that’s how you make friends.” Three discussed weight regulation and three noted the habit of smoking: “It keeps my hands busy.” Others mentioned the taste, as “a substitute for more harmful addictions,” and as part of a personal identity.

Cost was mentioned by 85% of participants as a motivator to quit. Half referenced the health effects, though these were not HIV-specific. The unpleasant smell of cigarettes on the body, clothing, or the room was noted by eight and the stigma against smokers was noted by several: “if you smoke anywhere within a square mile of an infant, you’re the devil.” Other reasons to quit included dependence (n=3), having to go outside (n=2), dry mouth or throat (n=1), and “losing family to cancer.” (n=1). Five said they did not have concerns related to smoking and health, with statements such as “My doctor is concerned about my pneumonia, but he hasn’t related it to my smoking” and “I don’t have any (concerns). I mean I know it’s bad for me, but …”

Half of participants reported that most people deemed as important in their lives also smoked, while 7 said others close contacts felt they should quit. Six said that although friends would support a quit, it would disrupt the friendships. Five felt they would be more likely to quit if someone close was quitting. Four said no one commented on their smoking, while two others said close contacts were more concerned about other problems—”They know I’m addicted to worse things.” Three said others’ opinions about their smoking had changed since the HIV diagnosis. All participants could identify important contacts who would support a quit, but they had difficulties articulating what would be helpful.

Behavior

Two participants never tried to quit. Ten reported previous use of nicotine patches and nine would use patches in a future quit attempt while seven would not. Concerns included skin irritation (n=3), insufficient craving reduction (n=2), do not satisfy “ritual” of smoking (n=2). Eight participants previously tried nicotine gum; three stated they would be willing to use it in the future, while one would not. The most common complaint was taste (n=3) and two felt it was too easy to “overdose”. Of the two participants who reported nicotine lozenge use, one experienced hiccupping, while the second “felt addicted.” Four individuals had tried non-nicotine prescription cessation medications: two experienced “crazy dreams,” upset stomach, and headache from varenicline; two tried bupropion - one experienced seizures and the other “felt short tempered.” Three stated they would be willing to try pills in the future.

Other behavioral skills related to cessation were cited by eight participants. Four mentioned substitution strategies, such as using food, coffee, or gum in place of cigarettes; three others used a taper strategy. One referenced “having a plan, writing things down.” Three participants had tried counseling, support groups, or quit lines, but stopped: “didn’t want them to know about my failure” and “too inconvenient.” Five would be willing to try this in the future, while 4 would not: “talking to strangers isn’t helpful,” (n=2), “talking on the phone makes me want to smoke,” and “it’s about your own willpower.”

Emotional coping skills for life stressors and for mood changes associated with quitting were commonly mentioned barriers to cessation (n=11). Additional barriers were the social aspects of smoking (n=7), “lack of will power,” (n=4), uncoupling activities associated with smoking (n=4), and side effects or other problems with cessation aids (n=4). Other barriers were “missing the ritual of smoking,” lack of other rewards, weight gain, and difficulty—”It’s too much work … want a quick fix, like a pill.”

Five participants mentioned medications as potential facilitators to a quit attempt. Five others felt new activities could replace smoking in their lives. Nonsmokers in their social network would be perceived as helpful by 3, while another 3 wanted a “nicotine-free cigarette” to satisfy the ritual of smoking. Two each cited more restrictions on smoking, provision of support services, or practicing behaviors such as saying no to offers of cigarettes. One mention each was made of having a quit partner, keeping hands wet or dirty so a cigarette cannot be held, and giving away money. Of the 20 participants, 4 expressed very low confidence in their ability to quit when ready. Most (n=13) expressed a low (n=7) or moderate (n=6) level of confidence. Three participants were extremely confident of success.

A hypothetical telephone program for living well with HIV was described and participants were asked whether they would consider participating if smoking was one of the topics covered. Eight participants said yes, and seven “maybe” or “unsure”, while five would not want to participate. Five said it would be okay to “check in” about smoking even if they were not ready to quit at that time; Seven said no, six said “maybe”, offering qualifiers, such as “it depends on how often.”

Discussion

Smoking is an important modifiable risk factor for people living with HIV. In this study of SLWH, we gained important insight into the level and type of knowledge about HIV-specific risks of smoking and motivation and behavioral skills regarding cessation. One theme related to deficits in awareness of HIV-specific risks of smoking. Most participants did not have independent questions regarding HIV and smoking but when queried further, they could not articulate the negative effects related to smoking well. Our findings add to recent data suggesting SLWH carry misconceptions regarding the specific dangers of cigarette smoking(Pacek, Rass, & Johnson, 2017) or potential dangers of nicotine replacement therapy.(McQueen, Shacham, Sumner, & Overton, 2014) While participants noted that smoking was commonly mentioned at HIV clinic visits, nearly all were critical of how these discussions were conducted. Surprisingly, the criticisms were largely about the lack of information or options offered, suggesting an opportunity for providers to provide more in-depth education that was previously thought to be lesser yield in these patients. These findings add detail to previous results that suggest that SLWH are open to specific and increased levels of education on this topic.(Robinson, Moody-Thomas, & Gruber, 2012)

The most typical stimulus to continue smoking was for emotional regulation, which is a commonly cited reason for the general population as well. Given the higher rates of substance use, depression and other psychosocial issues in smokers and people living with HIV(Burkhalter, Springer, Chhabra, Ostroff, & Rapkin, 2005; Pence, Miller, Whetten, Eron, & Gaynes, 2006; Shirley, Kesari, & Glesby, 2013), these issues must also be addressed when considering a cessation program. Many participants cited a social influence of contacts who smoke, which is a difficult but important barrier to cessation to address. Our results suggest that ASOs may be an untapped venue to promote cessation and the group setting could help address this social barrier. The most frequent reason to quit cited was the high cost of cigarettes, adding to the literature showing that the cost of cigarettes is associated with cessation.(Contreary et al., 2015) An encouraging finding was that most participants had at least one previous quit attempt and most indicated it would be okay to raise the topic of cessation, even if they were not ready to quit at that time, including incorporation of a telephone-based intervention.

Based on our findings, HIV-specific information about the risks of smoking needs to be more available to providers caring for SLWH and providers should routinely provide evidence-based cessation resources to SLWH. Participants were open to a variety of cessation aids, including prescription medications and these should be offered more consistently. In conjunction with pharmacy counseling to minimize risk for adverse events, this represents an underutilized path for cessation in this population.

Findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. While attempts were made to recruit a diverse study group, there were only two recruitment sites, both in Wisconsin, and the majority of participants were of non-Hispanic white race. Therefore, generalizability is potentially limited by demographic characteristics and regional differences. Results may have been influenced by social desirability, although the focus on privacy and information-gathering during this qualitative study may decrease that. In addition, because of the nature of the study design that included a relatively prolonged telephone-based survey, this could have selected for individuals more willing to participate in telephone-based cessation interventions as well.

Our study has a number of strengths. Interviews identified IMB-based strengths and deficits that can be used to develop theory-based interventions for SLWH. The interviews were conducted by telephone, at a time and day chosen by the participant, helping to maximize privacy and ensure that individuals did not feel coerced to participate. These issues are likely important in the study of smoking in SLWH, but also likely in successful cessation programs. Qualitative studies such as this lay the groundwork for interventional work in this area.

In conclusion, few SLWH are provided information regarding the HIV-specific risks of smoking. Cessation programs for SLWH are more likely to be successful if the concerns specific to this population are addressed within that program. Participants responded positively to more education and discussion about cessation, including telephone-based interventions and future studies should evaluate programs with this multifactorial approach.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

The authors wish to thank the patients and clinic staff who made this study possible. We especially appreciate the assistance of Dawn Boh with recruitment.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel Liaisons and Staff. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respiratory Care. 2008;53(9):1217–22. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18807274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Anderson J, Oleske JM, Libman H, Currier JS … HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;39(5):609–29. doi: 10.1086/423390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter J, Springer C, Chhabra R, Ostroff J, Rapkin B. Tobacco use and readiness to quit smoking in low-income HIV-infected persons. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(4):511–522. doi: 10.1080/14622200500186064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9738608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreary KA, Chattopadhyay SK, Hopkins DP, Chaloupka FJ, Forster JL, Grimshaw V … Community Preventive Services Task Force. Economic Impact of Tobacco Price Increases Through Taxation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(5):800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crothers K, Goulet JL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Gibert CL, Butt AA, Braithwaite RS, … Justice AC. Decreased awareness of current smoking among health care providers of HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative veterans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(6):749–54. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0158-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Shuper PA, Trayling C … LifeWindows Team. Computer-based intervention in HIV clinical care setting improves antiretroviral adherence: the LifeWindows Project. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(8):1635–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9926-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Cornman DH, Norton WE, Fisher WA. Involving behavioral scientists, health care providers, and HIV-infected patients as collaborators in theory-based HIV prevention and antiretroviral adherence interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2006;43(Suppl 1) Supplement 1:S10–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248335.90190.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(3):455–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1594721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Fisher JHJ. The Information-Motivation Behavioral Skills Model as a general model of health behavior change: Theoretical approaches to individual-level of change. In. Social Psychological Foundations of Health. 2003:127–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2005–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;65(44):1205–1211. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. http://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6544a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11556941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifson AR, Neuhaus J, Arribas JR, van den Berg-Wolf M, Labriola AM, Read TRH for the I. S. S Group. Smoking-Related Health Risks Among Persons With HIV in the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy Clinical Trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(10):1896–1903. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamary EM, Bahrs D, Martinez S. Cigarette Smoking and the Desire to Quit Among Individuals Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2002;16(1):39–42. doi: 10.1089/108729102753429389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen A, Shacham E, Sumner W, Overton ET. Beliefs, Experience, and Interest in Pharmacotherapy among Smokers with HIV. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(2):284–296. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mdodo R, Frazier EL, Dube SR, Mattson CL, Sutton MY, Brooks JT, … RMG Cigarette Smoking Prevalence Among Adults With HIV Compared With the General Adult Population in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162(5):335. doi: 10.7326/M14-0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Tailored Group Smoking Cessation Intervention for HIV-Infected Smokers. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;61(2):208–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182645679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Rass O, Johnson MW. Knowledge about nicotine among HIV-positive smokers: Implications for tobacco regulatory science policy. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;65:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Miller WC, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Gaynes BN. Prevalence of DSM-IV-Defined Mood, Anxiety, and Substance Use Disorders in an HIV Clinic in the Southeastern United States. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;42(3):298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KP, Parker RA, Losina E, Baggett TP, Paltiel AD, Rigotti NA, … Walensky RP. Impact of Cigarette Smoking and Smoking Cessation on Life Expectancy Among People With HIV: A US-Based Modeling Study. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;214(11):1672–1681. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds NR, Neidig JL, Wewers ME. Illness representation and smoking behavior: a focus group study of HIV-positive men. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC. 2004;15(4):37–47. doi: 10.1177/1055329003261969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivet Amico K. A situated-Information Motivation Behavioral Skills Model of Care Initiation and Maintenance (sIMB-CIM): an IMB model based approach to understanding and intervening in engagement in care for chronic medical conditions. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(7):1071–81. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W, Moody-Thomas S, Gruber D. Patient perspectives on tobacco cessation services for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2012;24(1):71–76. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.582078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley DK, Kaner RJ, Glesby MJ. Effects of Smoking on Non-AIDS-Related Morbidity in HIV-Infected Patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;57(2):275–282. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley DK, Kesari RK, Glesby MJ. Factors Associated with Smoking in HIV-Infected Patients and Potential Barriers to Cessation. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27(11):604–612. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss ACJ. Grounded Theory Methodology. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1994:273–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vidrine DJ, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. The effects of smoking abstinence on symptom burden and quality of life among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(9):659–66. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]