Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors represent a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that arise from neuroendocrine cells and secrete various peptides and bioamines. While gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors, commonly called carcinoids, account for about 2/3 of all neuroendocrine tumors, they are relatively rare. Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors originate from intestinal enterochromaffin cells and represent about 1/4 of small intestine neoplasms. They can be asymptomatic or cause nonspecific symptoms, which usually leads to a delayed diagnosis. Imaging modalities can aid diagnosis and surgery remains the mainstay of treatment. We present a case of a jejunal neuroendocrine tumor that caused nonspecific symptoms for about 1 year before manifesting with acute mesenteric ischemia. Abdominal X-rays revealed pneumatosis intestinalis and an abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography confirmed the diagnosis. The patient was submitted to segmental enterectomy. Histopathological study demonstrated a neuroendocrine tumor with perineural and arterial infiltration and lymph node metastasis. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient denied any adjuvant treatment.

Keywords: Small intestine, Carcinoid, Enterochromaffin cells, Jejunum, Enterectomy, Pneumatosis intestinalis

Core tip: The current case report underlines the indolent clinical course with nonspecific symptoms of a small intestine carcinoid that finally caused acute intestinal ischemia. This case also emphasizes the importance of simple imaging modalities, such as X-rays and the abdominal sonography, in the work-up of a patient with intestinal ischemia.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), commonly called carcinoids, are relatively quite rare, only representing approximately 0.5% of all human cancers. Their incidence is reported to be 1-2 cases per 100000 individuals per year[1]. The increased incidence of these tumors being reported in recent years can probably be explained by increased awareness and increased detection through new imaging techniques. While small intestine NETs are in general rare tumors, the ileum represents the commonest NET site of the human body[1]. Patients with NETs of the small intestine can manifest symptoms due to the local effect of the primary tumor, enlarging metastases or, indirectly, from secretion of hormones. These tumors tend to grow slowly, which explains their long and indolent course; this slow growth, in combination with their nonspecific symptoms, results in a high level of misdiagnosis[1,2]. When a GI NET is suspected, initial imaging is with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and then somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with SPECT/CT are the standard approaches. In all other instances, the imaging modalities used would depend on the patient’s symptomatology[3-7]. While the diagnosis of intestinal ischemia is usually established using contrast enhanced CT, and simple X-ray and abdominal ultrasound only sometimes aid the diagnosis, the present report underlines the importance of using simple imaging modalities, such as X-rays and abdominal sonography, in the work-up of a patient with intestinal ischemia originating from a midgut carcinoid. In localized disease, surgery is the mainstay of treatment[8-10]. In locally advanced and metastatic disease, new treatment modalities, such as octreotide and interferon, have led to longer survival rates[11].

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old female presented to our emergency department with worsening abdominal pain, vomiting and symptoms of intestinal obstruction. The initial disease onset was one year prior to presentation in the emergency department, with episodes of crampy and paroxysmal abdominal pain, which led her to seek medical treatment. A previous abdominal computed tomography demonstrated distal small bowel thickening, but no further workup was performed due to clinical improvement.

Clinical examination revealed a diffuse abdominal tenderness, and laboratory exams showed severe leukocytosis with neutrophilia (WBC = 20000/mm3) and increased CRP (4.7 mg/dL). Arterial blood gas revealed mild metabolic acidosis (pH: 7.32, PaO2: 87 mmHg, PaCO2: 37 mmHg, bicarbonate: 19 mmol/L, lactate: 2.3 mmol/L) and normal coagulation tests (PT: 13.1 s, INR: 1.07, APTT: 28.3 s). All other biochemical tests were within the normal limits.

Abdominal X-ray demonstrated a dilated small bowel loop with intestinal pneumatosis (Figure 1). This was also confirmed in an ultrasound exam, during which the affected loop was found to be slightly thickened, with no peristalsis and with intraluminal content and intestinal wall pneumatosis (Figure 2). The intramural gas pattern, along with the presence of fluid in the Douglas pouch, raised the suspicion of mesenteric ischemia. The abdominal CT angiography demonstrated a small bowel loop with wall thickening, pneumatosis, dilatation of the lumen and adjacent mesenteric fat inflammation (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Plain abdominal X-ray depicts slightly dilated small bowel loop with pattern of intramural pearls of air (black arrows).

Figure 2.

Sonographic features show dilated small bowel loop with absent peristalsis. Also depicted are increased intraluminal secretions within the ischemic small bowel segment (white arrow), slight mural thickening and intramural gas (black arrows).

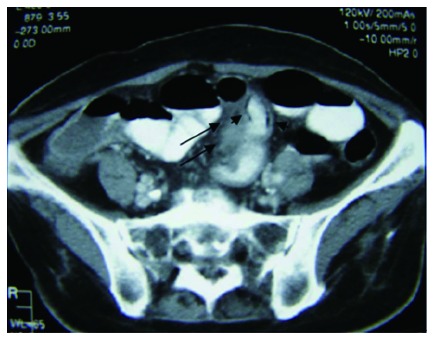

Figure 3.

Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography demonstrates intestinal pneumatosis (long black arrow).

Figure 4.

Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography demonstrates a homogeneous thickened soft tissue mass at the small bowel mesentery (long black arrows), as well as intestinal pneumatosis (small black arrows).

Based on the radiologic and clinical findings, the patient was submitted to exploratory laparotomy due to the possibility of mesenteric ischemia. During surgery, the small bowel was thickened and dilated and gross areas of ischemic bowel were present with full thickness necrosis (Figure 5). A segmental enterectomy was performed. Ligation of the mesentery revealed several enlarged lymph nodes adjacent to the jejunal mesenteric arterial branches. Approximately 1m of the jejunum was resected and a side-to-side anastomosis was performed. There was no evidence of other metastatic disease.

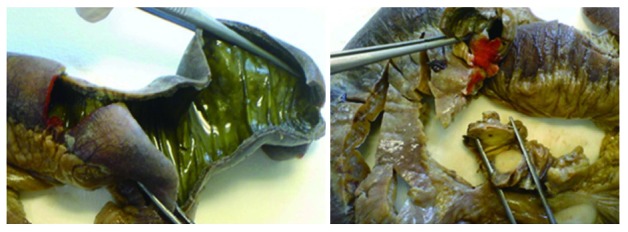

Figure 5.

Intraoperative findings.

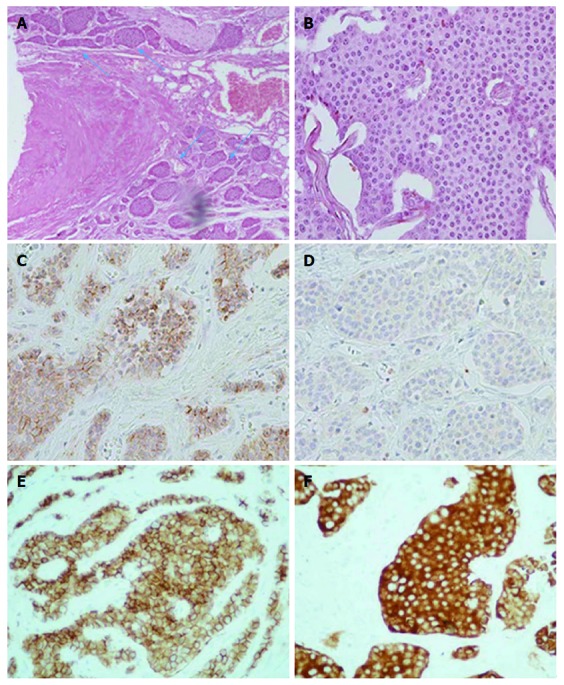

Histopathological study of the specimen revealed areas of ischemia with destroyed mucosa and two neoplastic foci of well-differentiated low-grade neuroendocrine tumors that infiltrated the muscularis propria and the adjacent fat tissue (Figure 6). The surgical margins were free, but vascular and perineural invasion was noted (Figure 7A). Interestingly, infiltration of the peripheral mesenteric artery was identified. Three out of twenty lymph nodes were infiltrated (Figure 6). Immunohistological stains for chromogranin A (Figure 7C), CD56 (figure 7E) and synaptophysin (Figure 7F) were positive and stains for ki 67 showed less than 1% proliferation (Figure 7D). The mitotic rate was < 2 per 10 high power fields (HPF).

Figure 6.

Gross pathology specimen of resected small bowel, showing ischemic bowel and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes.

Figure 7.

Histopathological findings. A: Vascular and perineural invasion of tumor cells (blue arrows), medium magnification (100 ×); B: Tumor cells with characteristic nuclear appearance, high magnification (400 ×); C: Immunohistochemical staining reveals strong positivity for chromogranin A marker, high magnification (400 ×); D: Less than 1% of tumor cells reveal positivity for proliferative marker Ki-67, high magnification (400 ×); E: Immunohistochemical staining reveals strong positivity for CD56 marker, high magnification (400 ×); F: Immunohistochemical staining reveals strong positivity for synaptophysin marker, high magnification (400 ×).

The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged on the 20th day. A whole-body pet octreotide scan and oncology consultation was recommended, but the patient denied any adjuvant treatments.

DISCUSSION

Nets consist of a heterogeneous tumor group which originate from neuroendocrine cells and secrete various bioamines and peptides[12]. The incidence of NETs has increased from 1.9 to 5.2 per 100000 people per year over the last three decades. Because of the slow growth pattern of NETs, along with their incidence, their prevalence is increased. The GI tract is the primary location of about 67% of NETs. These are also called GI NETs or carcinoids. Small intestine neuroendocrine tumors arise from intestinal enterochromaffin cells and can be recognized by typical tumor cell serotonin immunoreactivity. They account for 1/4 of all small intestine neoplasms and present at a mean age of 65 years with a slight male predominance[1,2,9,12]. Due to the absence of specific clinical manifestations except for the carcinoid syndrome, along with the absence of specific blood biomarkers, there is usually a notable delay in the establishment of the correct diagnosis[9,12]. Similarly, in our case, the patient suffered from atypical episodes of abdominal pain and loss of weight a year before she irreversibly deteriorated and presented to the emergency department.

Mesenteric metastases occur in high frequency and mainly concern the regional mesenteric and paraaortic lymph nodes. In a recent large series of patients with small intestine NET, mesenteric metastases presented on 93% of operated patients at operation, whereas 61% also had liver metastases[9,12]. When the liver is involved, carcinoid syndrome may develop. In this case, a constellation of symptoms manifests, including flushing, diarrhea, bronchoconstriction and cardiac disease. These symptoms result from the non-inactivation, by monoamine oxidase in the liver, of serotonin and other vasoactive substances which are secreted by the tumor cells. Thus, these substances reach the systemic circulation by escaping the liver metabolization[13]. In our patient, liver disease was not present, which contributed to the elusive course of the disease.

The usual clinical manifestations of carcinoid tumors in the small intestine vary, but commonly include postprandial and colicky pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, obstruction and loss of appetite. However, a high percentage of cases may be asymptomatic[9]. Similarly, our patient presented weight loss and mild abdominal pain with no specific characteristics. The disease can also manifest catastrophically as a carcinoid abdominal crisis. In this case, the protruded symptoms are those of intestinal ischemia as a result of obstruction of the mesenteric artery due to infiltrated paraaortic lymph nodes or the development of elastic vascular sclerosis provoked by tumor-produced hormones[14,15]. However, in our case, the mesenteric lymph nodes adjacent to the arterial jejunal branches provoked intestinal ischemia with no other evidence of a carcinoid abdominal crisis. The elastic tissue infiltration probably led to chronic obstruction of the jejunal arteries and the deterioration of mesenteric circulation led to ischemia. Elastic vascular sclerosis and tumor vascular infiltration were identified in the pathologic examination of the specimen, thus proving the pathophysiology of ischemia. The pathogenesis of elastic sclerosis is related to a desmoplastic reaction associated with hormones produced by the carcinoid tumor and consists of the formation of an elastic tissue layer on the endothelium of the vasculature, diminishing its diameter[16-18]. In our case, the hormones produced by the carcinoid were not sufficient to develop a carcinoid clinical syndrome, but they were probably the cause of a severe desmoplastic reaction. However, because of the urgency of the case, we did not measure the hormones.

The establishment of a diagnosis is usually challenging. It demands a great level of suspicion, and usually the final diagnosis is only settled after a long course of expensive and futile laboratory and imaging examinations. Depending on the prominent symptoms, the work-up series differs. In the case of gastrointestinal bleeding, the used imaging modalities are endoscopy of the gastrointestinal tract, red blood scintigraphy and computed tomography[19]. In the case of intestinal obstruction, the primary used imaging modalities are computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In the event of mesenteric ischemia, the standard approach is CT angiography[20]. In the current case, abdominal X-rays and ultrasound raised the suspicion of mesenteric ischemia, which was confirmed subsequently by CT angiography; however, the small intestine carcinoid was not depicted. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (octreoscan) can detect suspected neuroendocrine tumors and their metastases. It has 90% sensitivity and is very efficient for the identification of extra-abdominal tumor spread and can even demonstrate bone metastases better than bone isotope scan. It is also useful for staging neuroendocrine tumors, evaluating recurrence, determining somatostatin-receptor status and selecting patients with metastatic tumors for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT)[21-23]. Finally, PET with the serotonin precursor 5-Hydroxytryptophan labelled with 11C or 68Ga with the highest sensitivity in identifying GI NETs and has been used increasingly to diagnose GI NETs, stage the disease and monitor the effects of therapy. FDG-PET imaging can be utilized to detect both intermediate-grade and high-grade poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (ki > 15%), but it will not visualize low-grade well-differentiated lesions[4].

Surgery represents the mainstay of treatment for localized tumors and can be curative as it provides a 5-year survival rate from 80% to 100% in resectable tumors. So far, surgical treatment is the only curative option[8-10]. Apart from the indisputable value of surgical extirpation of the tumor, which is mandatory even in cases of metastatic disease, somatostatin analogs (lanreotide and octreotide) are the backbone of medical treatment for most functioning NETs, as their use may by stabilizing tumor growth and alleviating symptoms improve the quality of life. For the majority of patients with well-differentiated advanced midgut NETs, somatostatin analogs are appropriate for first-line systemic medical treatment and are very well tolerated[24]. IFNa has the potential also to control hormonal symptoms and inhibit tumor growth, but its usage is limited by its toxicity. Most guidelines suggest that IFNa should be given as second-line agent in patients with tumor progression or refractory carcinoid syndrome on somatostatin analogs [25]. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy is actually an internal radiation therapy that depends on delivering therapeutic doses of radiation inside tumor cells. Radiolabeled somatostatin analogues, which have high affinity to somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sstr2), are preferred in therapeutic use. Any tumor should be potentially treated if sstr2 overexpression is documented and confirmed on diagnostic somatostatin receptor imaging or histopathologically[22-24].

Recently, systemic chemotherapy agents and new molecular-targeted agents, such as everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, and sunitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, have been approved for the treatment of well-differentiated pancreatic NETs, but their roles are not clear in GI NETs. These drugs are currently being evaluated in ongoing clinical trials[26,27]. The responses to these treatments should be evaluated by both imaging, including CT and MRI, and biochemical markers, mainly chromogranin A which is a stable marker that more importantly can be measured during long-term treatment of both non-functioning and functioning tumors[28,29].

During treatment with biological therapy or cytotoxic agents or PRRT, patients with malignant NETs should be followed every 3 mo in order to evaluate response to treatment. Patients who were submitted to curative surgery are usually followed at 3 to 6 mo intervals for > 5 years with biochemical testing performed every 3 mo and imaging every 6 mo[30,31].

The establishment of guidelines and the new therapeutic modalities concerning the management of NETs has contributed significantly to the improvement of the quality of life and survival of many patients with malignant NETs. Thus, patients with NETs today exhibit a median survival at centers of excellence of more than 16 years [31].

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 70-year-old female with acute abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction with a 1-year medical history of nonspecific paroxysmal abdominal pain.

Clinical diagnosis

Clinical examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness.

Differential diagnosis

Intestinal obstruction due to colonic tumor or acute mesenteric ischemia.

Laboratory diagnosis

Severe leukocytosis with increased CRP and mild metabolic acidosis.

Imaging diagnosis

Abdominal X-ray, abdominal ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed intestinal pneumatosis, which was compatible with the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia.

Pathological diagnosis

Small bowel ischemia and two neoplastic foci of well-differentiated low-grade neuroendocrine tumor.

Treatment

Segmental enterectomy and side-to-side anastomosis

Related reports

A high percentage of small bowel neuroendocrine tumors may be asymptomatic and the clinical symptoms vary and are nonspecific. They can manifest as a carcinoid abdominal crisis, where the protruded symptoms are those of intestinal ischemia as a result of obstruction of the mesenteric artery due to the development of elastic vascular sclerosis provoked by tumor-produced hormones or due to the infiltration of paraaortic lymph nodes.

Term explanation

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors were previously and are still commonly called carcinoids.

Experiences and lessons

Small bowel neuroendocrine tumors are highly misdiagnosed because they can be asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms, but they can also manifest as acute abdomen. In most cases of intestinal ischemia, the diagnosis is established using contrast-enhanced CT; simple X-rays and abdominal ultrasound can establish the diagnosis in some cases. Therefore, simple imaging modalities should not go unnoticed, as they can aid diagnosis.

Peer-review

This paper reported a rare case of midgut neuroendocrine tumor presenting with acute intestinal ischemia. It provided sufficient data.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed consent statement: The patient provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest.

Peer-review started: September 3, 2017

First decision: September 21, 2017

Article in press: October 26, 2017

P- Reviewer: Armellini E, Cui J, Katada K, Naito Y, Shafik AN S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

Ioannis Mantzoros, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece. iorestis@auth.gr.

Natalia Antigoni Savvala, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Orestis Ioannidis, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Styliani Parpoudi, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Lydia Loutzidou, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Despoina Kyriakidou, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Angeliki Cheva, Department of Pathology, General Hospital “G. Papanikolaou”, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Vasileios Intzos, Department of Radiology, General Hospital “G. Papanikolaou”, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

Konstantinos Tsalis, Fourth Surgical Department, Faculty of Health Science, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, “G. Papanikolaou” General Hospital, Thessaloniki 57010, Greece.

References

- 1.Landerholm K, Zar N, Andersson RE, Falkmer SE, Järhult J. Survival and prognostic factors in patients with small bowel carcinoid tumour. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1617–1624. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Wayne JD, Ko CY, Bennett CL, Talamonti MS. Small bowel cancer in the United States: changes in epidemiology, treatment, and survival over the last 20 years. Ann Surg. 2009;249:63–71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulier B, Pringot J, Gielen I, Maldague P, Broze B, Ramboux A, Clausse M. Carcinoid tumor of the small intestine: MDCT findings with pathologic correlation. JBR-BTR. 2007;90:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganeshan D, Bhosale P, Yang T, Kundra V. Imaging features of carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:773–786. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mrevlje Z, Stabuc B. Pitfalls in diagnosing small bowel carcinoid tumors. J BUON. 2006;11:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Zhang GB, Yan L, Wei XE, Zhang YZ, Li WB. CT and enhanced CT in diagnosis of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s00261-011-9836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pusceddu S, Femia D, Lo Russo G, Ortolani S, Milione M, Maccauro M, Vernieri C, Prinzi N, Concas L, Leuzzi L, et al. Update on medical treatment of small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16:969–976. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2016.1207534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich AC, Kim MK. Surgical Intervention and Racial Differences in Small Intestinal Carcinoid Tumors. Gastroenterology. 2010;138 Suppl 1:S632. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunitake H, Hodin R. The Management of Small Bowel Tumors. In , Cameron JL, Cameron AM. Current Surgical Therapy. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. pp. 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farley HA, Pommier RF. Surgical Treatment of Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2016;30:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavel M, Kidd M, Modlin I. Systemic therapeutic options for carcinoid. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:84–99. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung DC. The Enigma of Carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:14–15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Öberg K. Carcinoid Syndrome. In: ameson JL, De Groot LJ, editors. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Kjell. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. pp. 2615–2627. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeal JE. Mechanism of obstruction in carcinoid tumors of the small intestine. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971;56:452–458. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.4.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ormandy SJ, Parks RW, Madhavan KK. Small bowel carcinoid tumour presenting with intestinal ischaemia. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54:42–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yener O. Intestinal ischaemia associated with carcinoid tumor: a case report with review of the pathogenesis. Prague Med Rep. 2013;114:43–47. doi: 10.14712/23362936.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deVries H, Wijffels RT, Willemse PH, Verschueren RC, Kema IP, Karrenbeld A, Prins TR, deVries EG. Abdominal angina in patients with a midgut carcinoid, a sign of severe pathology. World J Surg. 2005;29:1139–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7825-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey JN, Denyer ME, DaCosta P. Intestinal infarction caused by carcinoid associated elastic vascular sclerosis: early presentation of a small ileal carcinoid tumour. Gut. 1989;30:691–694. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.5.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreis DJ Jr, Guerra JJ Jr, Saltz M, Santiesteban R, Byers P. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to carcinoid tumors of the small intestine. JAMA. 1986;255:234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonekamp D, Raman SP, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Role of computed tomography angiography in detection and staging of small bowel carcinoid tumors. World J Radiol. 2015;7:220–235. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i9.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergsma H, van Vliet EI, Teunissen JJ, Kam BL, de Herder WW, Peeters RP, Krenning EP, Kwekkeboom DJ. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) for GEP-NETs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:867–881. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodei L, Kidd M, Paganelli G, Grana CM, Drozdov I, Cremonesi M, Lepensky C, Kwekkeboom DJ, Baum RP, Krenning EP, et al. Long-term tolerability of PRRT in 807 patients with neuroendocrine tumours: the value and limitations of clinical factors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:5–19. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2893-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sowa-Staszczak A, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Tomaszuk M. PRRT as neoadjuvant treatment in NET. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;194:479–485. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27994-2_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) [Web site] Rock-ville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). [cited; 2017. Guideline summary: Somatostatin analogues for the management of neuroendocrine tu-mours; p. Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.guideline.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carcinoid Tumors After Failure of Somatostatin Analogs: a Randomized Phase III of Octreotide Lutate Peptid Receptor Radionu-clide Therapy (PRRT) Versus Interferon α-2b. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Web site]. [cited 2017 Aug 13] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT01860742.

- 26.Öberg K. Biotherapies for GEP-NETs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:833–841. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Öberg K. Universal everolimus for malignant neuroendocrine tumours? Lancet. 2016;387:924–926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korse CM, Taal BG, de Groot CA, Bakker RH, Bonfrer JM. Chromogranin-A and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: an excellent pair of biomarkers for diagnostics in patients with neuroendocrine tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4293–4299. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rorstad O. Prognostic indicators for carcinoid neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:151–160. doi: 10.1002/jso.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Öberg K, Knigge U, Kwekkeboom D, Perren A; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine gastro-entero-pancreatic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 7:vii124–vii130. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delle Fave G, Kwekkeboom DJ, Van Cutsem E, Rindi G, Kos-Kudla B, Knigge U, Sasano H, Tomassetti P, Salazar R, Ruszniewski P; Barcelona Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with gastroduodenal neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:74–87. doi: 10.1159/000335595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]