Abstract

Background and Purpose

We compare our institutional outcomes of synchronous primary (SP) lung lesion patients with non-SP patients.

Materials and Methods: From an IRB approved prospective registry of 445 NSCLC patients treated with SBRT (8/2005 8/2012), 26 (5.8%) had SPs by biopsy or PET/CT. SBRT was delivered on a Novalis/BrainLAB platform with daily Exactrac set-up.

Results

There were no significant differences comparing SP vs non-SP groups for age, Charlson score, smoking pack years, and PET SUV (p=ns). 18 (69%) SP patients had at least one lesion biopsied. Ipsilateral and bilateral SPs were seen in 10 (38.4%) and 16 (61.6%) respectively. 77% received 50 Gy / 5 fx. SP vs non-SP median follow up was 12 (range 1.5-49.8) vs 15.2 months. Median survival for SP vs non-SP groups was 20.7 vs 28.4 months (p=0.3). In SP vs non-SP groups, local failure was 4% vs 7.6% (p=ns) and nodal/distant failure was 23% vs 24.6% (p=ns). Patients with ipsilateral and bilateral SPs had a 50% vs 14% distant failure respectively (p=0.037).

Conclusions

After SBRT, there were no differences in survival and patterns of failure for SP vs non-SP patients. Ipsilateral SPs had significantly worse distant failure compared to bilateral SPs.

Keywords: lung cancer, synchronous lesions, SBRT, non-small cell lung cancer

1. Introduction

Patients diagnosed with two synchronous lesions in the lung present a diagnostic quandary; do they represent synchronous primary (SP) tumors or pulmonary metastasis? The correct diagnosis and staging have implications for patient treatment and prognosis [1]. While estimates of this clinical scenario are 5-15% of all new lung cancer diagnoses, improving imaging capabilities and closer follow up in high risk patients will likely increase future incidence. Multiple lung primary lesion criteria initially published in 1975 by Martini and Melamed and later revised by Antakli have helped guide diagnosis and surgical management for SP patients [2, 3]. There have been many published surgical series in the SP population; however, due to a combination of factors including surgical morbidity and undetected metastatic disease, survival outcomes of SP patients have been mixed [2-5].

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has established itself as a safe and effective treatment for medically inoperable early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with local control that compares well to surgery [6-10]. However, there are limited SBRT data for medically inoperable patients presenting with SPs. Sinha et al reported on 10 SP patients treated with SBRT with limited toxicity, excellent local control, and no deaths [11]. While this experience suggested that SBRT can be used safely and effectively in the SP population, other published studies have reported poor survival. For example, Creach et al published on 15 SP patients treated with SBRT confirming limited treatment toxicity but poor overall survival of 27.5% at 2 years [12].

In this study, we present our experience of medically inoperable SP patients treated concurrently to both lung lesions with SBRT. Patterns of failure and outcomes are compared to our institutional medically inoperable non-SP patients.

2. Methods and materials

All patients treated with lung SBRT at our institution are enrolled in an IRB-approved prospective registry. Medically inoperable NSCLC patients treated from August 2005 through August 2012 were included, and patients treated for NSCLC SPs were considered for this analysis. Primary lesions diagnosed over 12 months from each other were excluded. Each primary lesion fulfilled at least one criteria: 1) biopsy confirmation 2) increasing lesion size on serial CT scan with spiculated appearance and hypermetabolism on PET, and/or 3) FDG PET maximum SUV>5. If the risk of pneumothorax in a patient was determined to be excessive clinically, the lesion was not biopsied. Whole body FDG-PET/CT and contrast brain MRI completed staging. Mediastinal staging by endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) was rare and prompted by non-specific hypermetabolism in the nodes seen on PET scanning. In the absence of both PET defined regional nodal disease and distant metastatic disease, patients were treated with SBRT simultaneously to each primary lesion. All SP patients had no more than 2 lesions and had no other active cancer diagnosis. Clinical staging was per AJCC 7th edition as cT3, cT4, or cM1a if the SPs were in the same lobe, same lung, or different lung respectively [13].

Our institutional approach to SBRT has been previously described [14]. Briefly, patients were immobilized and simulated supine with abdominal compression to limit tumor excursion less than 1.0 cm. Patients were planned with BrainScan 5.31 (BrainLAB, Feldkirchen, Germany) and treated on a Novalis system with an ExacTrac stereotactic body positioning system. Target volumes and critical structure definitions were defined per RTOG 0236 [10]. SBRT dose/fractionation was the same for each SP lesion and chosen according to physician preference. All SP patients treated on this study had lesions that required separate PTVs; satellite nodules that were planned with a single PTV were not included in the SP group. If the SPs were anatomically close together, a single isocenter was used. All other patients were planned with 2 different isocenters.

After treatment, routine follow-up included history, physical exam, and CT chest without contrast every 3 months for the first 2 years and every 4-6 months thereafter. Post-treatment PET/CT was only performed to diagnose possible tumor recurrence. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 3.0 was used to evaluate toxicity.

Statistics were generated using JMP Pro 10 (SAS, Cary, NC). Median values with ranges are reported. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to calculate differences between groups for patient and tumor factors, recurrence rates, and patterns of failure. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of completion of SBRT using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test. Correlation between patient/tumor factors and recurrence within the SP group was done using partition analysis. Threshold values presented in our analysis were identified from partition analysis.

To reduce the effect of confounder variables in our outcomes comparison, a matched pair analysis between SP and non-SP patients was conducted. To determine the most significant matching variables for recurrence and survival, univariate and multivariate models were constructed. We selected a 2:1 (non-SP:SP) match as there were more non-SP patients to match and to increase our statistical power by a factor of 1.33. A 2:1 match also provides the same number of tumors in each group.

For analysis of SP patients, clinical staging is reported by AJCC 7th edition criteria (cT3, cT4, cM1a) and tumors are individually staged based on size criteria (T1, T2, T3).

3. Results

Of the 437 NSCLC patients identified in our database, 26 patients (5.9%) with 52 tumors were diagnosed with SPs and 419 patients with 419 tumors were in the non-SP group. No statistical differences were seen in patient and tumor factors between SP and non-SP cohorts (Table 1). Treatment schedules for the two groups are reported in Table 2. Median follow-up for SP and non-SP groups was 12 months (1.5 – 50.4) and 15.2 months (0 – 91) respectively.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics of SP and non-SP groups.

| SP | Non-SP | Matched non-SP | |

| Patients | 26 | 419 | 44 |

| Male | 11 (42%) | 219 (47.6%) | 18 (41%) |

| Caucasian | 81% | 81% | 38 (86%) |

| Median age (y) | 75 (range 50 – 93) |

75 (range 41 – 97) |

75 (range 55 – 88) |

| Median smoking (py) | 40 (range 3 – 86) |

50 (range 0 – 250) |

50 (range 0 – 180) |

| Smoking at time of SBRT | 2 (7.7%) | 76 (18%) | 6 (14%) |

| Median KPS | 80 (range 60 – 100) |

80 (range 40 – 100) |

80 (range 50 – 90) |

| Median Charlson score | 3 (range 0 – 8) |

2 (range 0 – 10) |

3 (range 1 – 9) |

| Median tumor size (cm) | 2.0* (range 0.8 – 7.1) |

2.2 (range 0.0 – 10.0) |

2.25 (range 1.2 – 7.2) |

| Median PET SUV | 6.7* (range 1.0 – 59) |

7.3 (range 1.3 – 35) |

8.62 (range 2.0 – 27.8) |

| cT3 | 5 (19.2%) | ||

| cT4 | 5 (19.2%) | ||

| cM1a | 16 (61.5%) | ||

| Tumors | 52 | 419 | 44 |

| T1 | 36 (69%) | 311 (74%) | 32 (73%) |

| T2 | 15 (29%) | 105 (25%) | 11 (25%) |

| T3 | 1 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (2%) |

Including all SP lesions

Table 2.

SBRT treatment schedules of SP and non-SP groups.

| SP | Non-SP | |

| 50 Gy / 5 fx | 20 (77%) | 188 (44.8%) |

| 60 Gy / 3 fx | 2 (7.7%) | 109 (26%) |

| 30 Gy / 1 fx | 2 (7.7%) | 50 (12%) |

| 48 Gy / 4 fx | 1 (3.8%) | 25 (6%) |

| 60 Gy / 8 fx | 1 (3.8%) | 7 (1.7%) |

| 34 Gy / 1 fx | 0 | 15 (3.6%) |

| 50 Gy / 10 fx | 0 | 19 (4.5%) |

| Other | 0 | 6 (1.4%) |

For SP patients, 18 (69%) had biopsy proven NSCLC of at least one lesion, and three (11.5%) of both lesions. Of the three that had both SPs biopsied, 1 patient had similar histology in both SPs while 2 had different histologies in their respective SPs. The most common histology was adenocarcinoma (9 lesions) followed by squamous cell carcinoma (8), large cell carcinoma (2), NSCLC NOS (1), and adenosquamous carcinoma (1). Five biopsies were not diagnostic and 26 lesions were not biopsied, however these lesions fulfilled PET/CT criteria to treat as malignancy. Nine patients had a previous lung malignancy and 3 patients had a non-lung malignancy (prostate, bladder, and thyroid); all these patients had a no evidence of disease interval greater than 3 years. In the non-SP group, 127 (30%) had a prior history of cancer with 62 (15%) having a prior history of lung cancer with a disease interval greater than 3 years.

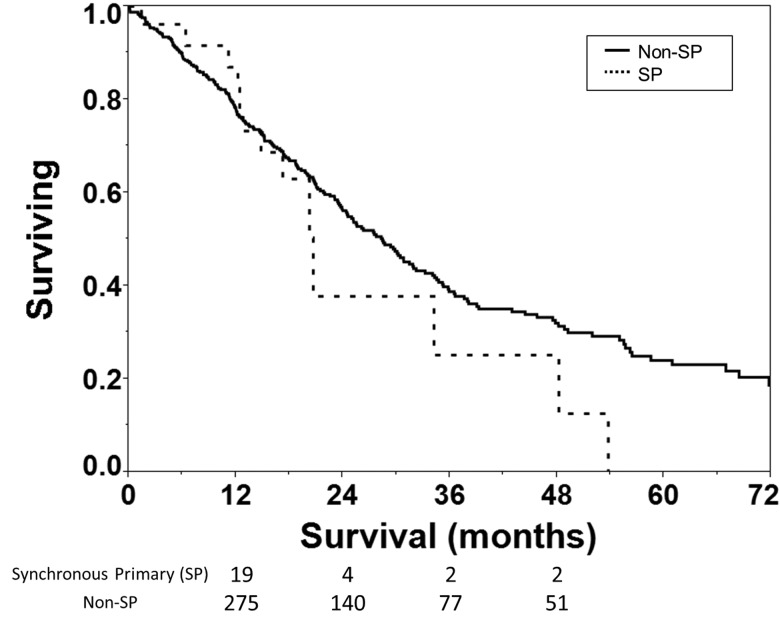

With regard to outcomes, in the SP group, 7 patients (27%) recurred with a median time to failure of 10.3 months. First recurrences were observed in the same lobe, mediastinal nodes, and distantly in 1 (4%), 3 (11%), and 3 (11%) SP patients respectively. By comparison, in the non-SP group, 135 (32.2%) patients recurred. Thirty two non-SP patients (7.6%) had local failures (margin and lobar failures), 34 (8.1%) had regional nodal failures, and 69 (16.5%) had distant failures (Table 4). Median overall survival for SP vs non-SP cohorts was 20.7 months vs 28.4 months and not statistically different (Figure 1 and Table 3; p = 0.3). Mean survival was 26.5 months in the SP group vs 38 months for the non-SP group (p = ns).

Table 4.

Patterns of failure for the SP and non-SP groups

| SP | Non-SP | |

| Total recurrences | 7 (26.9%) | 135 (32.2%) |

| Local failure | 1 (3.9%) | 32 (7.6%) |

| Regional failure | 3 (11.5%) | 34 (8.1%) |

| Distant failure | 3 (11.5%) | 69 (16.5%) |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of medically inoperable NSCLC patients with synchronous primary (SP, dashed) and non-SP (solid). Overall survival is not significantly different by log-rank test (p=0.3). Number of patients at risk is shown below the x-axis.

Table 3.

Median follow up, median survival, and mean survival in months for the SP and non-SP groups.

| SP | Non-SP | |

| Median follow up | 12 | 15.2 |

| Median survival | 20.7 | 28.4 |

| Mean survival | 26.5 | 38 |

The 6 SP patients (23%) that developed regional/distant failure died of metastatic disease. For these 6 patients, the median size of lesions was 1.65 cm (range 1.4 – 7.1 cm) and median SUV was 5.9 (range 3.3 – 16.9). However, there was no correlation between size of lesions or SUV with regional/distant failure or death. Of note, the only patient with biopsy proven SPs with similar histology recurred distantly and died of metastatic disease suggesting that in our similar histology patient, the synchronous lesions may have been metastatic. Other causes of death were CHF or MI in 2 (8%), pulmonary disease in 2 (8%), leukemia in 1 (4%), and unknown cause in 1 (4%).

In the SP group, 10 patients had ipsilateral SPs and 16 had bilateral SPs. On partition analysis, 5 (50%) patients failed in the unilateral SP group while 2 (14%) patients failed in the bilateral SP group (p=0.037). For the 5 patients with unilateral SPs, those who were cT3 and cT4, had a 40% and 60% distant failure respectively (p=ns).

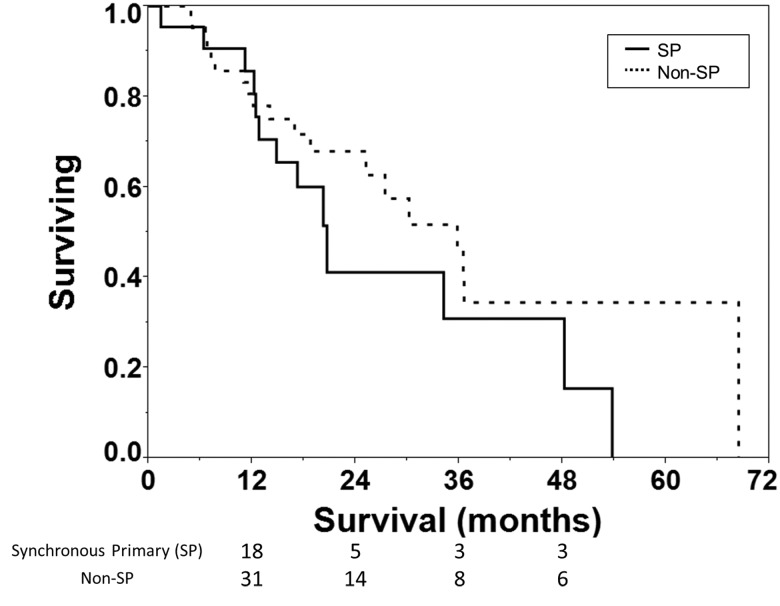

To increase statistical power, a 2:1 non-SP:SP matched pair analysis with a total of 66 patients (44 non-SP : 22 SP) with 88 tumors (44 non-SP : 44 SP). Using both univariate and multivariate models, matching factors that were significantly correlated with failure (p<0.01) were treatment start, Charlson score, and CT diameter of largest lesion. Smoking status was not significant in this analysis. SPs were matched to non-SPs based on these three factors: treatment start (+/- 3 months), Charlson score (+/- 1), and diameter of largest lesion (+/- 0.5 cm). All patients matched within our tolerance for treatment start date and most patients matched for size and Charlson score. Compared to the SP group, the non-SP group matched on 27 patients with 6 having a larger size and 11 having a smaller size beyond the threshold +/- 0.5 cm. For Charlson score, 30 patients matched with 5 having a higher Charlson and 9 having a lower Charlson score beyond the threshold of +/- 1. Overall survival in the matched population for the SP and non-SP patients was not statistically different (p=0.189 on logrank test; Figure 2) with median survival of 20.7 months and 36 months for SP and non-SP groups respectively. The patterns of failure for the two groups were also not statistically different (p=ns; Table 5).

Figure 2.

Survival of synchronous primary (SP, solid) and non-SP (dashed) patients from the matched pair analysis with median survival of 21 vs 36 months respectively. Log-rank test shows this difference is not statistically significant (p=0.189). Number of patients at risk is shown below the x-axis.

Table 5.

Patterns of failure from matched pair analysis showing no significant difference between SP and non-SP using Fisher’s exact test.

| SP | Non-SP | p value | |

| Local failure | 9.1% | 7.3% | 1 |

| Regional failure | 13.6% | 14.7% | 1 |

| Distant failure | 20% | 19.5% | 0.755 |

In the SP group, SBRT was well tolerated with 1 patient (4%) developing grade 3 chest wall pain, 3 (12%) with grade 2 chest wall pain, and 2 (8%) with grade 2 pneumonitis. No patients died of treatment related toxicity. One patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to SBRT due to misdiagnosed metastatic disease; no other patients received chemotherapy as part of their overall SP treatment course. One patient developed a brain metastasis within 1 year after completing SBRT and was treated with stereotactic radiosurgery.

4. Discussion

This study of 26 patients represents a relatively large series of medically inoperable SP patients treated to both lesions concurrently with SBRT. Our results show that using SBRT to treat SPs simultaneously is safe and has low toxicity. Overall survival and patterns of failure are not statistically different comparing SP patients with institutional non-SP patients in both cohort and matched-pair analyses.

The published experience of SBRT in medically inoperable SP patients is relatively new. The Indiana University experience of 10 SP patients had outcomes including 80% no evidence of disease, 100% survival rate with median follow up 18.5 months, and no reported grade 3 or higher toxicity [11]. On the other hand, Creach et al reported on 15 patients with SPs, and found overall survival was extremely poor 27.5% at 2 years after being treated with SBRT [12]. Workup included PET/CT, but brain imaging was not required. A smaller series published by Matthiesen et al showed better overall outcomes with 8 SP patients having 60% survival at 18 months [15]. Mancini et al also reported their SBRT experience with 17 SP patients having a similar survival and local control compared to non-SP patients [16]. Griffioen et al report 2 year survival of 56% in 56 SP patients with limited toxicity [17].

Median survival for Stage IV NSCLC is less than 1 year [18] and our SP group had a median survival of 20.7 months. As metastatic recurrence typically occurs soon after treatment [10], we believe our SP patients most likely did not have pulmonary metastases. Historically, different SP definitions were used. For example in the surgical series by Reinmuth et al, SPs are defined as any new lesion within 2 years of a previous early stage NSCLC [5]. In most studies including this series, SPs are defined as lung lesions diagnosed within 1 year.

Surgical and SBRT experiences of SP patients have both shown no significant survival difference between NSCLC patients with ipsilateral and bilateral SPs [12, 19]. While we found no survival difference between the two groups (p=ns), there was a significant difference in metastatic failure (p=0.037) favoring better distant control in patients with bilateral SPs compared to unilateral SPs. This result is similar to that published by Griffioen et al [17]. From partition analysis of patients that had bilateral lesions, if the sum of the SP diameters was less than 4.1 cm, there was a higher rate of metastatic failure. While a larger burden of disease (ie greater sum of SP diameters) would seem to carry a higher risk of metastatic failure, we speculate that bilateral small tumors may be an early sign of a metastatic process. For ipsilateral tumors, there were less ipsilobar failures compared to non-ipsilobar failures. The numbers of failures within this subgroup was small and further study is needed.

From past surgical series, the Martini/Melamed/Antakli criteria have provided guidance to define an SP; patients need to have at least 2 of the following to be diagnosed an SP: 1) anatomically distinct, 2) associated premalignant lesion, 3) no systemic metastases, 4) no mediastinal spread, and/or 5) different DNA ploidy. Confirming different histology, a scenario encountered in 15% of SP cases [20], would be the diagnostic gold standard, however presented with the same histology, the decision tree is less clear as it could represent two distinct primaries with similar histology or metastases. Staging the mediastinum in published surgical series of SP patients has shown excellent outcomes. For example, Shah et al have suggested assessing N2 nodes by mediastinoscopy [21].

In medically inoperable patients, invasive diagnostic testing is not always recommended due to medical contraindication making clinicians rely primarily on imaging. From PET/CT in our series, 2 patients had enlarged mediastinal nodes without true lymphadenopathy, and 1 patient was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis making it difficult to assess for regional metastatic disease. As these lymph nodes could not be safely biopsied due to medical comorbidities, our clinical judgment indicated these lesions were synchronous and not metastatic. Thus, we recommended SBRT with the caveat that these patients may have an increased risk of failure because of the increased possibility of nodal disease. Only 4 of our most recently treated SP patients had mediastinal staging by EBUS. Presumably, with routine mediastinal staging, outcomes for SP patients may be improved.

For patients in which EBUS or biopsy is not recommended, radiographic criteria are used, but there has been no consensus algorithm. Dijkman et al suggested that DSUV on FDG-PET may aid SP diagnosis in some patients [22]. In our series, on partition analysis, patients with DSUV > 6.9 had 43% chance of failure compared to patients with DSUV < 6.9 with a 21% chance of failure (p=ns). A more robust radiographic criteria is needed in this patient population.

AJCC 7th edition lung cancer staging includes an assessment of synchronous lung lesions in T3, T4, and M1a corresponding, in the absence of nodal disease, to Stage IIB, IIIA, and IV; however, these stratifications imply that patients with SPs do as poorly compared to others in the same stage. While this may have been true in historical surgical series, our series indicates that with adequate workup, we can select an SP population clinically staged cT3, cT4, and cM1a with outcomes closer to early stage NSCLC. This seems especially true for SP patients with bilateral lesions who have significantly less failure compared to SP patients with unilateral lesions in our series. These results suggest that bilateral SPs represent a field cancerization phenomenon while unilateral SPs represent a mix of both metastatic disease and field cancerization. While these findings require confirmation, we suggest that patients with bilateral SPs with no evidence of regional/distant disease be staged according to each of their primary lesions.

While our series represents a large SP experience treated with SBRT, it is nonetheless a small absolute number of patients. Caveats to our analysis include that several tumors did not undergo biopsy; however, many of our patients undergoing SBRT were not eligible for a biopsy due to the perceived risk of potential complications, mainly due to their baseline pulmonary status. Although we could not biopsy all lesions in this study, all patients without pathologic diagnosis had CT scans compatible with NSCLC and the lesions were avid on FDG-PET. Additionally, we found no significant difference in outcomes between patients who did or did not undergo biopsy in our series. It is also possible that some of these lesions that were not biopsied could represent the more indolent adenocarcinoma in-situ; however, because biopsy was medically contraindicated, after staging workup, and clinical judgment including multi-disciplinary tumor board consultation, we treated them as SPs. Referral patterns for both SP and non-SP patients were similar, reducing selection bias in our comparison of SP and non-SP groups.

5. Conclusion

SBRT is safe and effective for the treatment of medically inoperable patients with SPs of the lung. In our series, SP patients have similar survival and failure patterns compared to non-SP patients. Patients with bilateral SPs have a significantly lower rate of metastatic failure compared to patients with unilateral SPs, although this did not affect survival. Additional study and longer follow up is needed to better select appropriate SP patients for SBRT however, following appropriate diagnostic workup, for medically inoperable patients with SPs, we believe SBRT should be recommended.

References

- 1. Dacic S. Dilemmas in lung cancer staging. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012; 136: 1194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975; 70: 606-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Antakli T, Schaefer RF, Rutherford JE, Read RC. Second primary lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 59: 863-6; discussion 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fabian T, Bryant AS, Mouhlas AL, Federico JA, Cerfolio RJ. Survival after resection of synchronous non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011; 142: 547-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reinmuth N, Stumpf A, Stumpf P, Muley T, Kobinger S, Hoffmann H, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with second primary lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Videtic GM, Stephans KL. The role of stereotactic body radiotherapy in the management of non-small cell lung cancer: an emerging standard for the medically inoperable patient? Curr Oncol Rep. 2010; 12: 235-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Videtic GM, Stephans K, Reddy C, Gajdos S, Kolar M, Clouser E, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy-based stereotactic body radiotherapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer: excellent local control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010; 77: 344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoopes DJ, Tann M, Fletcher JW, Forquer JA, Lin PF, SS Lo, et al. FDG-PET and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007; 56: 229-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koto M, Takai Y, Ogawa Y, Matsushita H, Takeda K, Takahashi C, et al. A phase II study on stereotactic body radiotherapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2007; 85: 429-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, Michalski J, Straube W, Bradley J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010; 303: 1070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sinha B, McGarry RC. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for bilateral primary lung cancers: the Indiana University experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006; 66: 1120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Creach KM, Bradley JD, Mahasittiwat P, Robinson CG. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of multiple primary lung cancers. Radiother Oncol. 2012; 104: 19-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Atlas. 7th ed. ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stephans KL, Djemil T, Tendulkar RD, Robinson CG, Reddy CA, Videtic GM. Prediction of chest wall toxicity from lung stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012; 82: 974-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matthiesen C, Thompson JS, La De Fuente Herman T, Ahmad S, Herman T. Use of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable multiple primary lung cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012; 56: 561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mancini BR, Rowe BP, Chang BW, Decker RH. Comparative Analysis of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Multiple Primary Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012; 7: S252-3. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Griffioen GH, Lagerwaard FJ, Haasbeek CJ, Smit EF, Slotman BJ, Senan S. Treatment of multiple primary lung cancers using stereotactic radiotherapy, either with or without surgery. Radiother Oncol. 2013; 107: 403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cetin K, Ettinger DS, Hei YJ, O’Malley CD. Survival by histologic subtype in stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 3: 139-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagai K, Sohara Y, Tsuchiya R, Goya T, Miyaoka E. Prognosis of resected non-small cell lung cancer patients with intrapulmonary metastases. J Thorac Oncol. 2007; 2: 282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Trousse D, Barlesi F, Loundou A, Tasei AM, Doddoli C, Giudicelli R, et al. Synchronous multiple primary lung cancer: an increasing clinical occurrence requiring multidisciplinary management. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007; 133: 1193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shah AA, Barfield ME, Kelsey CR, Onaitis MW, Tong B, Harpole D, et al. Outcomes after surgical management of synchronous bilateral primary lung cancers. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012; 93: 1055-60; discussion 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dijkman BG, Schuurbiers OC, Vriens D, Looijen-Salamon M, Bussink J, Timmer-Bonte JN, et al. The role of (18)F-FDG PET in the differentiation between lung metastases and synchronous second primary lung tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010; 37: 2037-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]