Abstract

Due to the great development of light sources for several applications from displays to lighting, great efforts are devoted to find stable and efficient visible emitting materials. Moreover, the requirement of Si compatibility could enlarge the range of applications inside microelectronic chips. In this scenario, we have studied the emission properties of bismuth doped yttrium oxide thin films grown on crystalline silicon. Under optical pumping at room temperature a stable and strong visible luminescence has been observed. In particular, by the involvement of Bi ions in the two available lattice sites, the emission can be tuned from violet to green by changing the excitation wavelength. Moreover, under electron beam at low accelerating voltages (3 keV) a blue emission with high efficiency and excellent stability has been recorded. The color is generated by the involvement of Bi ions in both the lattice sites. These peculiarities make this material interesting as a luminescent medium for applications in light emitting devices and field emission displays by opening new perspectives for the realization of silicon-technology compatible light sources operating at room temperature.

Introduction

Luminescent thin films are gaining increasing attention as visible emitters for optoelectronic devices, bio imaging, drug delivery, solid state lasers as well as flat panel displays (FPDs)1. Among the display technologies, light emitting devices (LEDs) and field-emission displays (FEDs) have many advantages, such as low power consumption, good compactness, long lifetime, low weight to size ratio, high resolution, quick response, etc.2. However, being FEDs composed by an array of aligned field emitter tips cathodes opposite to a phosphor anode, their development has been limited by the complexity of the device fabrication and by the presence of contaminants released under the high-electron bombardment and related to the used phosphor. Therefore a big part of the scientific community working on FEDs is nowadays focused on the development of novel stable materials emitting in the visible range with high luminance, good chromaticity, long service time, high efficiency at low voltages (<5 keV)2,3. Similarly, for white or tunable LEDs application, many efforts are devoted to developing down-conversion luminescent materials for phosphor-converted LEDs (pc-LEDs) that are competitive in view of the low cost and the simplicity of the control circuit4,5. Different approaches have been already proposed by combining blue chips with yellow YAG phosphors or near UV (NUV) chips with separated red-green-blue (RGB) tricolor phosphors4. The better chromatic flexibility, higher stability and higher efficiency make NUV-based pc-LEDs expected to have great potential applications in the field of solid state lighting. Thus, nowadays a great interest is still generated in the development of new phosphors for blue, green, or red emission upon NUV excitation2–7.

In particular, the choice of activator ions and host materials are subject of investigation. For the first aspect, rare earth (RE) ions have been playing an important role due to the abundant emission colors in the whole visible range owing to their 4 f-4 f transitions, but unfortunately with very small excitation cross sections and thus low luminous efficiency and a poor controllability of emission colors. Thus REs ions exploiting 5d-4 f transitions, such as Eu2+ or Ce3+, have been preferred and recently also transition and post-transition metals have been proposed8,9, owing to their higher excitation cross section and peculiar optical properties. About the hosts, the most commercially available for FEDs are the sulfide-based ones, such as CaSO4:Tb, Na10, but unfortunately they suffer from some limits, such as the quick degradation due to the corrosive sulfide gases produced under high-electron bombardment2. To overcome these drawbacks, many alternative RE-doped nanomaterials11,12, and phosphors3,13, have been proposed, among whom several RE doped oxides, such as Y2SiO5:Ce3+ 14, LiAl5O8:Tb15 and ZnGaO2 16 and nitrides, such as Eu:AlN17, have been studied as possible solution.

In this work, we investigate the optical properties of bismuth doped yttrium oxide thin film, proposing it as a suitable efficient luminescent material for silicon-compatible pc-LEDs and FEDs technologies. Indeed, yttrium oxide is a transparent material that is considered a promising host for down- and up-conversion18–20 and for the realization of reliable luminescent devices, due to its good chemical durability, thermal stability, and low phonon energy. In addition, yttrium oxide thin film has been proven to be a well-adapted host to incorporate high concentration, up to 1022/cm3, of optically active trivalent ions in Y substitutional position20,21. Moreover, both the developed complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (C-MOS) compatible synthesis techniques used to realize good quality yttrium oxide thin films and its demonstrated high thermal stability on silicon22 make this host suitable for fabrication by using mainstream microelectronics large scale manufacture technique. Thus it could permit to enlarge the range of applications inside microelectronic chips. In particular bismuth has been demonstrated to be stabilized in Y2O3 in the optically active 3+ oxidation state21,23,24, that is characterized by permitted optical transitions from its ground state, 6 s2, to the first empty orbitals, thus resulting in a very high excitation cross section, up to 10−17 cm2 21,25, and very short radiative lifetime (~10 ns)24. In addition, since the 6 s electrons are not shielded by outer shells, such as for REs, the intensities and the positions of the emission peaks are strongly dependent on the local field felt by the ions, and therefore by the embedding host. Efficient green-blue emission from Y2O3:Bi3+ powders has been recently demonstrated26,27, while very few works report the optical properties of thin films28,29. Indeed, phosphor thin films have been recently proposed to replace the conventional powder phosphors due to several advantages, such as the lower operation voltage and the endurance to much higher power densities without degradation both for LEDs and FEDs. In addition, although the emission intensities are limited by the light trapping inside the luminescent layers, phosphor thin films also offer other strengths, such as higher contrast and resolution, better thermal stability, superior thermal conductivity, a high degree of uniformity and better adhesion to the substrate compared with the conventional display screen prepared by the direct deposition of phosphor grains2. These advantages make possible to define smaller pixel spot size, which is very important particularly for microdisplays.

Herein in particular, we will show the Y2O3:Bi optical properties under optical and electrical pumping by evidencing the excitation mechanisms of Bi ions and the perspectives of this material for the application in tunable pc-LEDs and in FEDs.

Results and Discussion

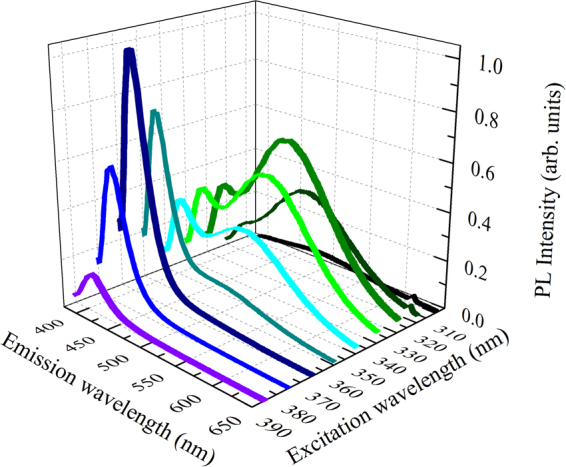

In order to study the optical properties of dissolved Bi ions in Y2O3 host, PL spectra have been firstly recorded by scanning the excitation wavelength, λexc, in the ultraviolet range between 300 nm and 400 nm that potentially can involve all the possible Bi oxidation states. Under these excitation conditions, no PL emission has been observed from the undoped thin film, since Y does not exploit radiative transitions. On the other hand, from the Y2O3:Bi thin film an intense PL emission has been detected in the visible range for all the excitation wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 1. By looking more deeply, the PL shape appears strongly dependent on the excitation wavelength. In particular, under λexc between 370 nm and 400 nm the PL emission is characterized by a peak in the blue region, centered at about 406 nm. By further decreasing λexc the peak intensity at 406 nm decreases, while a further contribution appears in the green region, centered at about 500 nm, whose intensity is increasing up to 330 nm excitation wavelength.

Figure 1.

Photoluminescence from Y2O3:Bi under UV excitation. The RT PL spectra are reported for several excitation wavelengths between 300 nm and 400 nm.

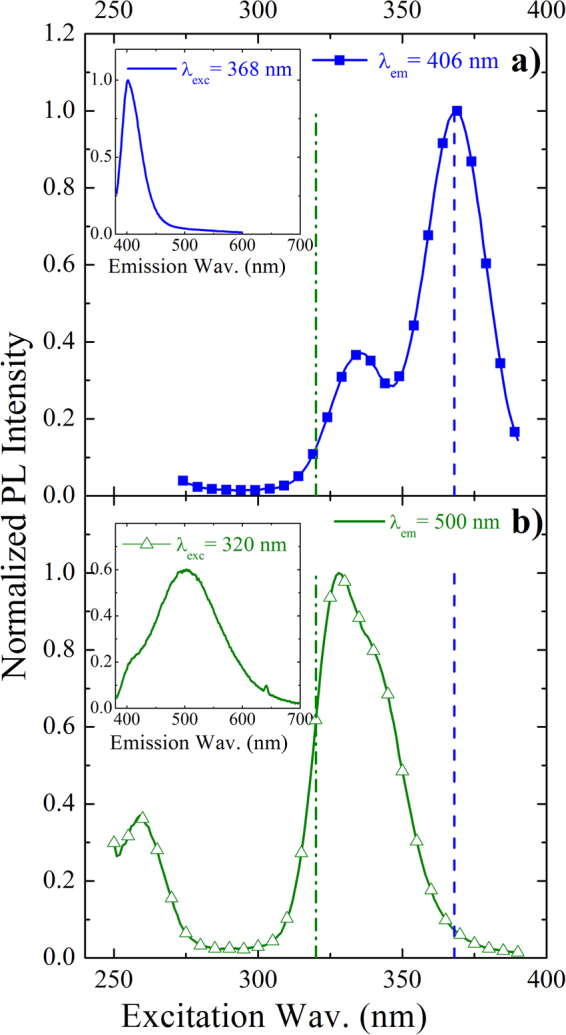

To elucidate the origin of these two features, photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectra have been recorded at 406 nm, reported in Fig. 2(a) as line and closed squares, and at 500 nm, in Fig. 2(b) as line and open triangles.

Figure 2.

Excitation and emission spectra of two Bi sites. RT normalized PLE spectra from Y2O3:Bi recorded at two different emission wavelengths: (a) at 406 nm, related to Bi3+ ions in C2 sites and (b) at 500 nm, related to Bi3+ ions in S6 sites. The relative emission bands of Bi under (a) 368 excitation wavelength and (b) 320 nm excitation wavelength are also shown as insets. The two chosen excitation wavelengths for the inserts are also indicated in the main panels as dashed lines.

The two excitation spectra appear totally different. In particular, for the blue emission the excitation spectrum is composed by the convolution of two peaks at about 334 nm and 368 nm (Fig. 2(a)), while for the green emission the correspondent excitation band seems to be composed by an asymmetric peak at around 330 nm and a further peak at about 258 nm (Fig. 2(b)). The two excitation bands around 350 nm can be attributed to the same transition of Bi3+ ions, 1S0 → 3P1, where the first excited energy level, 3P1, splits differently by depending on the site occupied by Bi3+ ion. Indeed, in our Bi-doped samples, Bi ions are well dispersed in the body centered cubic Y2O3 lattice in substitutional Y positions, as demonstrated by the unchanged XRD spectrum with respect to the undoped sample in ref.30, therefore Bi3+ ion can occupy two cation sites having different symmetries, named C2 (non-centrosymmetric, monoclinic symmetry) and S6 (centrosymmetric, rhombohedral symmetry)23,24. The sites are characterized by a different redistribution of the oxygen vacancies, in particular along the diagonal of the Y2O3 cubic cell for the S6 site and along one of the face diagonals for the C2 site. These different chemical surroundings induce strong variation in the crystalline field felt by the cation, by generating the different spectroscopic properties. In particular, when the emission wavelength is fixed at 406 nm in Fig. 2(a) the two excitation peaks at 334 nm and 368 nm can be associated to the 1S0 → 3P1 transition, where the 3P1 excited state splits in the doublet [3Au, 3Eu] typical of Bi3+ in the S6 site23. Therefore under 368 nm, corresponding to the 1S0 → 3P1(3Eu) transition of Bi3+ in S6 site, the sharp blue emission at 406 nm, FHWM of about 40 nm, in the insert of the same Fig. 2(a), is maximized. This blue emission, associated to the 3P1(3Eu) → 1S0 transition, is Stokes shifted23,24, with respect to the relative excitation band, as expected for the post-transition metals with ns2 electronic configuration. The Stokes shift was calculated to be 2543.36 cm−1 for the S6 site.

When the emission wavelength is fixed at 500 nm, the broad and asymmetric excitation band peaked at 330 nm in Fig. 2(b) can be ascribed to the same transition 1S0 → 3P1, where 3P1 splits in the triplet [3A, 3B, 3B] owing to the presence of the crystalline field and the occurrence of spin-orbit coupling when Bi3+ is in the C2 site. The additional excitation peak in the deep UV, at 258 nm, can be associated to the transition from 1S0 to the higher energy level 1P1, totally permitted by the selection rules24. Thus, when the sample is excited under 320 nm excitation, that is in resonance only with the excitation band of Bi3+ in the C2 site and out of resonance with the one of Bi3+ in the S6 site, the PL emission is characterized by a main broad peak at about 500 nm and with FHWM of about 135 nm, in the insert of Fig. 2(b). It can be associated to the convolution of the Bi3+ 3P1 (3A, 3B, 3B) → 1S0 (1A) transitions of Bi3+ ions in the C2 site. In this case, the broader PL shape and the larger Stoke shift (10120.48 cm−1) are due to the stronger asymmetric nature of the C2 site. Anyway, the Stokes shifts calculated for the S6 and C2 are compatible with those reported for the Y2O3:Bi3+ bulk powders prepared by conventional solid-state methods (2500 and 10000 cm−1 for the S6 and C2, respectively24).

In conclusion, the origin of the blue and green emissions is clearly associable to the same 1S0 → 3P1 Bi3+ transition respectively when Bi3+ ion is in the S6 and C2 site. Moreover, they can be alternatively switched on (or off) by properly varying the excitation wavelength since the respective excitation bands are maximized in different spectral regions. In the narrow region of overlap, between 345 and 355 nm excitation, the two contributions reach equal intensities by determining a broad PL emission ranging from 400 nm to 650 nm with a whole FWHM of 183 nm.

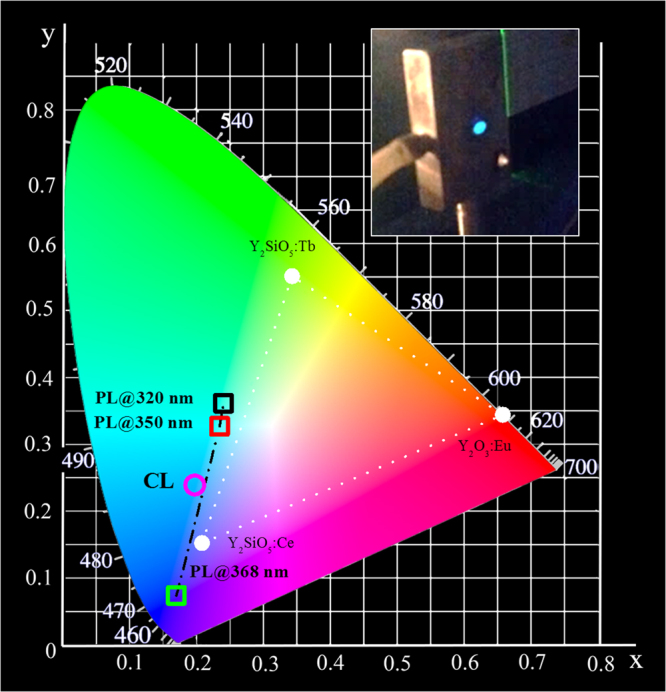

The PL emission from Bi is visible with the naked eye, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3 through a photograph of the Bi-doped sample under optical pumping at 320 nm excitation wavelength (only green light is observable). Under this excitation condition an internal quantum efficiency (IQE), defined as the ratio between the number of photons created and the number of photons absorbed, has been evaluated as the ratio of effective and radiative lifetime. By measuring the time resolved PL and known the radiative lifetime24,31, of Bi3+ in the C2 site, an IQE value of about 35% is obtained under 325 nm excitation. The obtained IQE value appears comparable or higher than the values reported in literature for powder systems, see for example the 4% efficiency reported for green emission of Mg2SnO4:Mn2+ powders8, or the reported value of 35.2% for Eu and Tb codoped silicate thin films32. The same estimation is also obtained by a measurement of the external quantum efficiency (EQE) evaluated as the ratio of the emitted power and the incident power by measuring the emitted power through a calibrated spectrometer. The obtained EQE value is equal to 0.05%. By taking into account the low extraction efficiency of the emitted photons from the planar thin film, due to internal reflection losses at the interface host/air, and the very low effective absorbed pumping power by the system ascribed only to the Bi3+ ions excitation (1S0 → 3P1), we have estimated a similar value of about 35% for IQE.

Figure 3.

Chromaticity coordinates diagram. The calculated coordinates related to the PL emission from Y2O3:Bi thin film under optical excitation at different excitation wavelengths from 300 nm to 400 nm are indicated as a dashed-dot line. In particular the coordinates related to 320 nm, 350 nm and 368 nm excitation wavelengths are highlighted as open squared symbols in the diagram. Instead the chromaticity coordinates under 3 keV electron beam excitation are reported as an open circle. The standard triangle for tricolor FED is also reported in the diagram: it consists of the three CIE chromaticity coordinate points of Y2O3:Eu, Y2SiO5:Tb, Y2SiO5:Ce34,35. In the insert a photograph of our Bi doped sample under 320 nm excitation.

In order to obtain the true color of the broad emission from the Y2O3:Bi sample, the color gamut of our light source was evaluated. This is an important index for determining the colors that a display could present, as determined by the location of the Commission International de l’Eclairage (CIE) coordinates of phosphors33. Figure 3 reports the calculated chromaticity coordinates diagram for the Y2O3:Bi with the tricolor gamut triangle used as reference for oxide-based FEDs34,35. The values obtained under optical pumping for the excitation wavelengths varying between 300 nm and 400 nm are highlighted with a black dashed-dot line. For example, under the 320 nm and the 368 nm excitation wavelengths, that selectively excite C2 or S6 sites, coordinates of (0.2403, 0.3594) and of (0.1725, 0.0736) have been obtained, respectively. Therefore, it is possible to tune the PL emission in a continuous way from the green to the violet by just tuning the excitation source, thus suggesting this material suitable as a switchable blue/green emitter for pc-LEDs. Moreover, the chromaticity coordinates associated to the PL emission obtained under 368 nm are very close to the ones of the pure blue (0.1666, 0.0089). It demonstrates higher color purity of our sample than the commercially available blue phosphor such as Y2SiO5:Ce35, reported in the diagram in Fig. 3.

To understand the potentialities of this luminescent thin films in FEDs, the emission under electron beam excitation was further investigated by cathodoluminescence (CL) measurements and compared with the PL properties. The electrons energy was chosen in order to center the electron scattering distribution (as evaluated by Monte Carlo simulations36,37), to the Bi3+ distribution profile in the film. The penetration depth, L, of the electron beam was also evaluated in a first approximation2 by the following formula

| 1 |

where A is the atomic or molecular weight of the material (225.78 for the undoped Y2O3 and 228.34 for Y2O3:Bi), ρ is the density (5.01 g/cm3 for Y2O3), Z is the atomic number (102.9) and E is the excitation voltage. Due to the fact that low voltage phosphors are currently required by the FEDs technology2, the beam acceleration energy was kept fixed at 3 keV. The estimated penetration depth for this energy was about 35 nm and the electron scattering distribution has been simulated to reach 92 nm in depth.

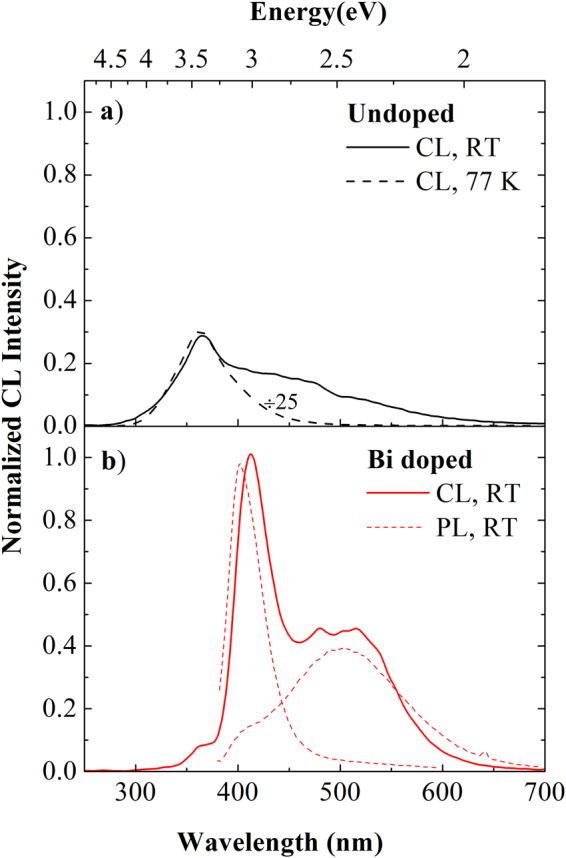

Figure 4 shows the comparison between the CL spectra from the undoped and Y2O3:Bi samples under 3 keV electron beam excitation. Differently from the optical excitation, an emission comes also from the undoped sample, as shown in Fig. 4(a): it is composed by a main peak at 363 nm overlapped with a less intense broad band in the visible range extended down to 600 nm. The nature of the main peak at 363 nm was clarified thanks to the CL measurements at low temperature: its intensity strongly increases, by a factor of 25, by decreasing the temperature up to 77 K without suffering from position shifts, while the visible band, that is kept unchanged, is almost not appreciable. The peculiar behavior of the emission at 363 nm can be ascribed to self-trapped excitons (STE)38,39. Indeed, in a variety of wide-bandgap non-semiconducting materials with sufficiently strong exciton–phonon interactions, the self-trapping of free excitons associated to lattice defects can occur. Radiative recombination of STE represents an intrinsic luminescence process, characterized by a broad emission spectrum40,41, that occurs when the excitation energies overcome the matrix band gap. The STE excitation condition are thus obtained under electron excitation and not under the investigated optical UV excitation.

Figure 4.

Emission spectra under electron beam excitation. CL spectra (a) of undoped Y2O3 thin film at RT and at 77 K and (b) of Bi doped Y2O3 thin film at RT under electron beam excitation at 3 keV and 5 nA. The intensities reported in the two panels are directly comparable. Figure 4 (b) reports also the PL emission spectra from Bi ions in the two sites from the same sample at RT.

Instead concerning the emission band extended down to 600 nm, the lower intensity as well as the co-presence of many not-well resolved bands did not allow us to unambiguously identify their origin. However, a broad emission falling in the visible range has been already observed, as in other inorganic oxides37,42, from bulk or powders Y2O3 38,43, but the origin was not fully discussed. Only a few works claim that it can be de-convoluted in a broad band at around 428 nm (2.9 eV), related to anion sublattice radiative de-excitation (O2+ + h+ + e− → O2− + e− → (O2−)∗ → O2− + hν43), and in higher-lying wavelengths bands ascribed to the radiative recombination of the excited donor−acceptor Y3+−O2− pairs, that contribute with different bands corresponding to various Y−O distance43. From the other side, we cannot exclude the further contribution from a few nanometers-thick interfacial silicon oxide layer formed after the annealing treatment, since it is well known that also SiOx layer exploits radiative transitions coming from defects in the same wavelength range44, such as for instance twofold coordinated silicon centers (at about 468 nm), carbon contaminants (at about 520 nm) and the Non Bridging Oxygen Hole Center (at 633 nm).

When the Bi-doped sample is excited under the same conditions at RT, a totally different CL spectrum is observed as reported in Fig. 4(b). The yttrium oxide STE contribution appears very low and the spectrum is mainly composed by a sharp emission peaked at 412 nm and by a broader contribution at around 500 nm. These two features well match the Bi3+ emission bands already observed under optical pumping (reported as dashed lines); in particular the sharp peak corresponds to the Bi3+ emission in the S6 lattice sites, while the broad visible band can be decomposed by a broad band peaked at about 512 nm corresponding to the Bi3+ emission in the C2 sites and a weaker contribution related to the radiative defect centers from the host and the interfacial silica layer, already observed in the undoped sample. Thus, under electrical pumping we observe luminescence from Bi in both lattice sites. The slight peaks shift (<10 nm) in the Bi3+ CL with respect to the PL could be ascribed to the presence of charge effects and local oxidation mechanisms45–47 that can lead to a shift of the 3P1 shell, since the energy position is strongly dependent on the ion environment. This mechanism is possible only under electron beam excitation, due to the much higher energy involved, 3 keV, with respect to the 3.8 eV of the exciting photons.

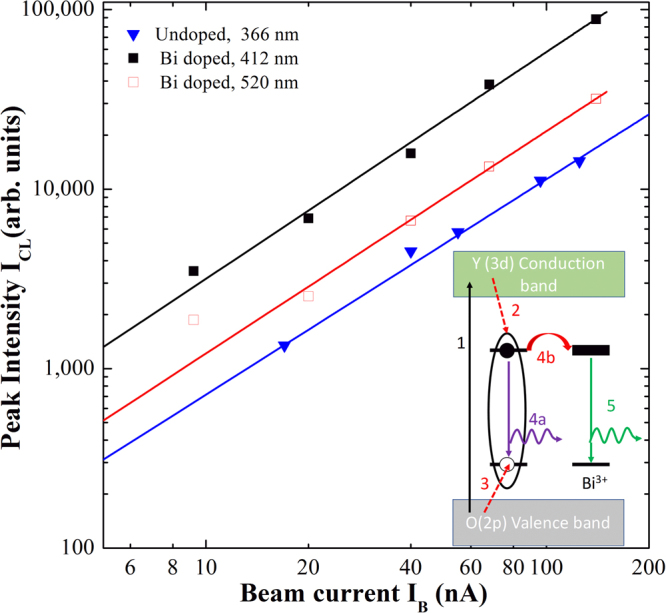

The CL emission was verified to be stable also after several hours of excitation conditions. To go further in testing the potentialities of Y2O3:Bi as a possible visible emitter in FEDs, we have investigated the dependence of the CL emission on the electron beam current (IB) in the range between 9 nA and 110 nA. Both for undoped and doped samples the emission shapes appear unchanged in all the investigated range. Therefore in Fig. 5 we have plotted the peak CL intensity at 366 nm for the undoped, corresponding to the STE emission, and at 412 nm and at 520 nm for the Bi-doped samples, corresponding respectively to the S6 and C2 site, as a function of the beam current.

Figure 5.

Cathodoluminescence – beam current relationship for undoped and doped samples. RT CL peak intensity versus beam current, recorded at 366 nm from undoped Y2O3 and at 412 nm and 520 nm from the doped film at RT under electron beam irradiation at 3 keV. The fits are also reported as continuous lines. A schematic of the proposed excitation mechanisms is reported as inset, starting from the above-gap excitation through highly energetic electrons (1), creation of the STE (2–3), STE emission (4a) or ET in presence of Bi (4b) and finally Bi emission (5).

Figure 5 shows that the CL intensity increases with the electron beam current for undoped and Bi doped sample. The dependence of CL intensity (ICL) on electron current density (j) can be described by a power law ICL ∝ jm 42, where the value m can give some information concerning the process involved in the excitation and de-excitation mechanisms as well as the nature of the involved emitting centers. By keeping constant the excited area during the CL measurements, it was possible to study the ICL dependence versus the beam current IB. We performed a fit of the experimental data in the log−log scale and the m values were extracted for both samples. The fits are reported in Fig. 5 as continuous lines, as well as the obtained m values. In details, a value of 1.20 ± 0.02 was obtained for the undoped sample and of 1.24 ± 0.02 and 1.26 ± 0.02 for the two emission peaks from the doped sample. The superlinear CL dependence on the current density has been demonstrated to be typical of recombination channels related to free and bound excitons48. Therefore, the obtained m value of 1.20 for the undoped Y2O3 further supports the occurrence of STE emission even at RT. Another interesting point is that under electronic excitation similar values are obtained also for the Bi emission at 412 nm and 520 nm in the doped sample, differently from the optical pumping where a simple linear dependence has been obtained (not shown). This behavior suggests also in this case the involvement of STE in the Bi excitation mechanisms. This claim is also supported by the strong reduction of the STE peak intensity observed when Bi is introduced. Indeed, in this respect we can suppose that an energy transfer (ET) process from the yttrium oxide STE to the Bi3+ ions in both sites occurs. This ET could be made possible by the large spectral overlap between the exciton emission band peaked at 363 nm (see Fig. 4) and the broad Bi excitation bands peaked at 330 nm and 368 nm for the C2 and S6 sites, respectively (see in Fig. 2(a) and (b)), as already suggested for Eu:Y2O3 39 and for RE-doped semiconductors41.

An evaluation of the cathodoluminescence efficiency was carried out following the methods by Shea and Walko49. This method allows an evaluation of the CL efficiency, considering the material properties and the electron excitation parameters, and it is comparable to the EQE. The CL efficiency with a beam current of 20 nA is 0.06% and 0.004% in the case of the Bi doped and the undoped material, respectively. Eventually, the chromaticity coordinates of the Y2O3:Bi light source under electron beam irradiation have been calculated and reported by a circle in Fig. 3 in comparison with the ones obtained under optical pumping. Color coordinates of (0.1972, 0.2377), corresponding to a light blue emission, have been obtained. These coordinates are outside those of the traditional FED tricolor gamut34,35, and they could be interesting to enlarge the FEDs color gamut when combined with RGB tricolor phosphors.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have discussed the emission properties of Bi-doped yttrium oxide thin films on c-Si. In particular, we have demonstrated that under optical pumping Y2O3:Bi exhibits a stable and strong visible luminescence at RT which can be tuned from violet to green by changing the excitation wavelength, due to the involvement of Bi ions in the two available lattice sites. Internal quantum efficiency of about 35% has been evaluated. Those data suggest the suitability of Bi-doped Y2O3 thin films as luminescent material for pc-LEDs, acting as a tunable violet-green light source or a pure blue source. Moreover, under electronic beam a light blue emission is obtained, being the convolution of the green and blue light from Bi in the two lattice sites, permitting to enrich the standard color gamut of FEDs. Bi excitation mechanisms have been explained as an energy transfer process between the Y2O3 STE and Bi ions, as evidenced by the superlinear CL behavior with the beam current. These results, together with the high emission efficiency under low accelerating voltages (3 keV) and the excellent stability, suggest the suitability of Bi-doped Y2O3 thin films as a pure light blue source in FEDs, and opening new perspectives for the realization of CMOS-compatible light sources operating at room temperature.

Materials and Methods

Materials synthesis

Undoped Y2O3 thin films were deposited on 5″ c-Si wafers by radio-frequency magnetron sputtering. The substrate was heated at 400 °C during the synthesis process and the power applied to the Y2O3 target was fixed at 500 W. We obtained a polycrystalline stoichiometric yttrium oxide film, 120 nm thick, as verified by Rutherford Back-scattering Spectrometry (RBS) and X-ray diffraction analyses (XRD). More details can be found in ref.20. Bi ions were then introduced by ion implantation at 270 keV, that results in a Bi profile spread over a thickness of about 80 nm and peaked at about 35 nm below the surface, as measured by RBS. The Bi dose was kept fixed at 2 × 1015 at/cm3 and the respective average Bi concentration was evaluated to be 3 × 1020 Bi/cm3. The undoped and as-implanted samples were then annealed at 800 °C for 30 min in oxygen atmosphere to recover eventual oxygen deficiencies and remove defects left over by the implantation process. The stoichiometry and dopant distribution were unchanged after annealing treatment. Also the polycrystalline structure was preserved. In particular, the body centered cubic crystalline structure of Y2O3 was identified by XRD30, that excludes the formation of crystalline Bi2O3, by demonstrating the good dispersion of Bi in the Y2O3 lattice in substitutional Y positions.

Optical Characterization

The optical properties of all the annealed undoped Y2O3 and Y2O3:Bi thin films have been analyzed by photoluminescence (PL) and photoluminescence excitation (PLE) spectroscopy at room temperature (RT), performed by a Horiba Fluorolog spectrofluorimeter equipped with a 400 W Xe lamp. The excitation wavelength was varied between 300 nm and 550 nm with a scan step of 1 nm, while the luminescence was detected by a Hamamatsu Photomultiplier.

Cathodoluminescence (CL) properties have been investigated using a commercial Oxford CL system, fitted onto a Cambridge S360 standard tungsten gun scanning electron microscope. The CL system is equipped with a 1800 line/mm grating and a multialkali photomultiplier sensitive in the range 350–830 nm. The spectroscopic CL analyses are carried out with an accelerating voltage of 3 kV at room temperature and at low temperature (liquid nitrogen, 77 K). The spectral resolution is 5 nm.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Italian Ministry for Education, University and Research (MIUR) through the PON project “Bio-nanotech Research and Innovation Tower” (BRIT) is acknowledged. The authors want to thank G. Franzò and S. Boninelli for useful discussions, S. Scalese and D. D’angelo for the equipment for EQE measurements, and C. Percolla, S. Tatì and G. Pantè for expert technical assistance.

Author Contributions

A.S. realized the Bi-doped yttrium oxide thin films and performed all the structural and optical characterizations; she contributed to data interpretation and wrote the paper. R.R. supervised the PL and PLE measurements and participated to data interpretation. F.F. and F.R. performed the CL measurements. F.F. contributed to the CL interpretation and to writing the paper. F.P. contributed to supervise the experiments, the data interpretation and the paper writing. M.M. conceived and supervised the project, interpreted data and wrote the paper. All authors participated to data discussion, reviewed the manuscript and approved its submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee, J., Liu, D., Wu, S. Field Emission Displays. Introduction to Flat Panel Displays, 233−254 (John Wiley & Sons: London, 2008).

- 2.Li G, Lin J. Recent progress in low-voltage cathodoluminescent materials: synthesis, improvement and emission properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:7099–7131. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00109E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Wang Q, Wang X, Ding X, Wang Y. Luminescence properties of Eu2+-doped BaSi2O5 as an efficient green phosphor for light-emitting devices and wide color gamut field emission displays. New J. Chem. 2016;40:8549. doi: 10.1039/C6NJ01831A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pust P, Schmidt PJ, Schnick W. A revolution in lighting. Nat. Mat. 2015;14:454–458. doi: 10.1038/nmat4270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Wang X, Huang J, Shi J, Gong M. Near UV-based LED fabricated with Ba5SiO4(F,Cl)6:Eu2+ as blue- and green-emitting phosphor. Opt. Mater. 2009;32:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2009.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JS, et al. White-light generation through ultraviolet-emitting diode and white-emitting phosphor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;85:3696–3698. doi: 10.1063/1.1808501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin Y, et al. Tunable blue-green color emitting phosphors Sr3YNa(PO4)3F:Eu2+, Tb3+ based on energy transfer for near-UV white LEDs. J. Lumin. 2017;185:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li G, et al. Cyan-emitting Ti4+- and Mn2+-coactivated Mg2SnO4 as a potential phosphor to enlarge the color gamut for field emission display. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:6477–6479. doi: 10.1039/c1jm00057h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu XM, Lin J. Enhanced luminescence of gadolinium niobates by Bi3+ doping for field emission displays. J. Lumin. 2007;122–123:700–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2006.01.264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakshmanan AR, et al. A quantum-splitting phosphor exploiting the energy transfer from anion excitons to Tb3+ in CaSO4: Tb, Na. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007;17:212–218. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200600010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li GG, et al. Electrospinning Derived One-Dimensional LaOCl: Ln3+ (Ln = Eu/Sm, Tb, Tm) Nanofibers, Nanotubes and Microbelts with Multicolor-Tunable Emission Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010;20:3446–3456. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201001114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal Y, et al. High-Performance Stable Field Emission with Ultralow Turn on Voltage from rGO Conformal Coated TiO2 Nanotubes 3D Arrays. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11612. doi: 10.1038/srep11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long Q, Wang C, Li Y, Ding J, Wang Y. Synthesis and investigation of photo/cathodoluminescence properties of a novel green emission phosphor Sr8ZnLu(PO4)7:Eu2+ J. Alloy. Compd. 2016;671:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.01.249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coetsee E, Swart HC, Terblans JJ. Cathodoluminescence degradation of Y2SiO5: Ce thin films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. 2007;25:1226–1230. doi: 10.1116/1.2429676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitale SS, et al. Cathodoluminescent properties and surface characterization of bluish-white LiAl5O8:Tb phosphor. J. Appl. Phys. 2011;109:013105. doi: 10.1063/1.3530607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang SH, Yokoyama M. Enhanced luminance of ZnGa2O4 phosphor by In2O3 doping. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A. 2001;19:2463–2467. doi: 10.1116/1.1387076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirosaki N, et al. Blue-emitting AlN: Eu2+ nitride phosphor for field emission displays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91:061101. doi: 10.1063/1.2767182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li R, et al. Monodisperse and hollow structured Y2O3:Ln3+ (Ln = Eu, Dy, Er, Tm) nanospheres: A facile synthesis and multicolor-tunable luminescence properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2014;617:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.08.118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robindro Singh L, et al. Luminescence study on Eu 3+ doped Y2O3 nanoparticles: particle size, concentration and core–shell formation effects. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:055201. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/05/055201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo Savio R, Miritello M, Cardile P, Priolo F. Concentration dependence of the Er3+ visible and infrared luminescence in Y2−xErxO3 thin films on Si. J. Appl. Phys. 2009;106:043512. doi: 10.1063/1.3195077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scarangella A, Reitano R, Franzò G, Priolo F, Miritello M. Enhancement of Er optical efficiency through bismuth sensitization in yttrium oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;107:041908. doi: 10.1063/1.4927833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evangelou EK, Wiemer C, Fanciulli M, Sethu M, Cranton W. Electrical and structural characteristics of yttrium oxide films deposited by rf-magnetron sputtering on n-Si. J. Appl. Phys. 2003;94:318–325. doi: 10.1063/1.1580644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobsohn LG, et al. Y2O3:Bi nanophosphor: Solution combustion synthesis, structure, and luminescence. J. Appl. Phys. 2008;104:124303. doi: 10.1063/1.3042223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Craats AM, Blasse G. The quenching of bismuth(III) luminescence in yttrium oxide (Y2O3) Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995;243:559–563. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(95)00897-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber MJ, Monchamp RR. Luminescence of Bi4Ge3O12: Spectral and decay properties. J. Appl. Phys. 1973;44:5495–5499. doi: 10.1063/1.1662183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Back M, et al. Energy Transfer in Bi-and Er-Codoped Y2O3 Nanocrystals: An Effective System for Rare Earth Fluorescence Enhancement. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:30071–30078. doi: 10.1021/jp5080016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jafer RM, et al. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and luminescent properties of Y2O3:Bi3+ phosphor. Appl. Surf. Science. 2015;332:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jafer RM, Swart HC, Yousif A, Coetsee E. The effect of different substrate temperatures on the structure and luminescence properties of Y2O3:Bi3+ thin films. Solid State Sci. 2016;53:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2016.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S-I, Kim S-I, Chang SK, Kim Y-H. Fabrication and characterization of Bi-doped Y2O3 phosphor thin films by RF magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Films. 2016;600:83–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2016.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scarangella, A., Reitano, R., Franzò, G., Priolo, F. & Miritello, M. Efficient energy transfer from Bi to Er ions in Y2O3 thin films. J. Lumin.191, 92–96 (2017).

- 31.Babin V, et al. Luminescence and excited state dynamics of Bi3+ centers in Y2O3. J. Lumin. 2015;167:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2015.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao D, Seo S-J, Bae B-S. Full-Color Mesophase Silicate Thin Film Phosphors Incorporated with Rare Earth Ions and Photosensitizers. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:3473–3479. doi: 10.1002/adma.200602562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitai, A. Luminescent materials and application (John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2008).

- 34.Xu X, et al. High luminescent Li2CaSiO4:Eu 2+ cyan phosphor film for wide color gamut field emission display. Opt. Express. 2012;20:17701–17710. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.017701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, et al. High luminescent Li2CaSiO4:Eu 2+ cyan phosphor film for wide color gamut field emission display. Opt. Express. 2012;20:17701–17710. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.017701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brillson LJ. Applications of Depth-resolved Cathodoluminescence Spectroscopy. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2012;45:183001. doi: 10.1088/0022-3727/45/18/183001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabbri F, et al. Depth-resolved cathodoluminescence spectroscopy of silicon supersaturated with sulfur. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013;102:31909. doi: 10.1063/1.4788743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bordun, O. M., Bordun, I. M. & Novosad, S. S. Luminescence centers in Y2O3. J. App. Spectrosc. 62, 1060–1063 (1995).

- 39.Engelsen, D. D. et al. Ultraviolet and blue cathodoluminescence from cubic Y2O3 and Y2O3:Eu3+ generated in a transmission electron microscope. J. Mater. Chem. C4, 7026–7034 (2016).

- 40.Pelant, I. & Valenta, J. Luminescence of excitons in Luminescence Spectroscopy of Semiconductors. (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 41.Braud, A. Excitation Mechanisms of RE Ions in Semiconductors in Rare Earth Doped III-Nitrides for Optoelectronic and Spintronic Applications. (Springer 2010).

- 42.Yacobi, B. G. & Holt, D. B. Cathodoluminescence. Cathodoluminescence Microscopy of Inorganic Solids. 73–82 (Springer−Verlag: New York, 1990).

- 43.Bordun OM. Influence of oxygen vacancies on the luminescence spectra of Y2O3 thin films. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2002;69:430. doi: 10.1023/A:1019763518857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salh, R. Defect Related Luminescence in Silicon Dioxide Network: a Review, Crystalline Silicon - Properties and Uses. 136–172 (ed. Sukumar Basu, InTech, 2011).

- 45.Mikhail, P., Hulliger, J. & Ramseyer, K. Cathodoluminescence and Photoluminescence of Smn+ (n = 2, 3) in Oxide Environments. Solid State Commun.112, 483–488 (1999).

- 46.Wang, X., Liu, Z., Stevens-Kalceff, M. A. & Riesen, H. A Facile Method for the Preparation of Eu2+-doped Nanocrystalline BaFCl. Mater. Res. Bull.48, 3691–3694 (2013).

- 47.Bellocchi, G., Fabbri, F., Miritello, M., Iacona, F. & Franzò, G. Multicolor Depth-Resolved Cathodoluminescence from Eu-Doped SiOC Thin Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces7, 18201–18205 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Phillips, M. R., Telg, H., Kucheyev, S. O., Gelhausen, O. & Toth M. Cathodoluminescence Efficiency Dependence on Excitation Density in n-Type Gallium Nitride. Microsc. Microanal.9, 144–151 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Shea, L. E. & Walko, R. J. Development of standards for characterization of cathodoluminescence efficiency. Proceedings of SPIE3636, 105 (1999).