Abstract

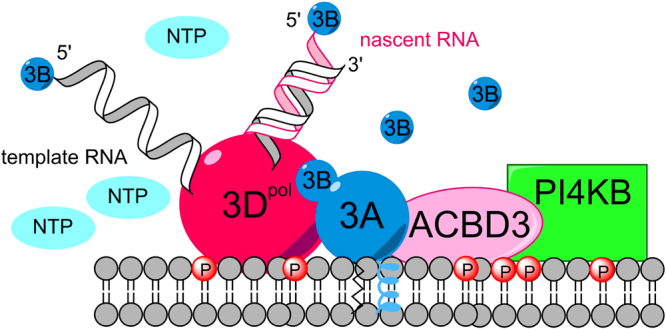

Most single stranded plus RNA viruses hijack phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases (PI4Ks) to generate membranes highly enriched in phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P). These membranous compartments known as webs, replication factories or replication organelles are essential for viral replication because they provide protection from the innate intracellular immune response while serving as platforms for viral replication. Using purified recombinant proteins and biomimetic model membranes we show that the nonstructural viral 3A protein is sufficient to promote membrane hyper-phosphorylation given the proper intracellular cofactors (PI4KB and ACBD3). However, our bio-mimetic in vitro reconstitution assay revealed that rather than the presence of PI4P specifically, negative charge alone is sufficient for the recruitment of 3Dpol enzymes to the surface of the lipid bilayer. Additionally, we show that membrane tethered viral 3B protein (also known as Vpg) works in combination with the negative charge to increase the efficiency of membrane recruitment of 3Dpol.

Introduction

Space in the capsids of small viruses is limited and small viruses do not encode every enzymatic activity required for their replication. Single stranded plus RNA (+RNA) viruses replicate at replication organelles (also known as replication factories or membranous webs) which provide an optimal replication environment and also protection from innate immunity1. Membranous webs are highly enriched in the signaling lipid PI4P (phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate), yet +RNA viruses do not encode phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases (PI4Ks). Instead, they hijack a human enzyme, either PI4KA or PI4KB (also called PI4K IIIα or PI4K IIIβ)2–7. The other two human PI4K isoforms, PI4K2A and PI4K2B (also known as PI4K IIα or PI4K IIβ), are palmitoylated proteins8, and this posttranslational modification possibly renders them a more difficult target for viruses to recruit. It is also possible that the different subcellular localization of different PI4K enzymes is the reason why PI4KB and PI4KA are hijacked by viruses and PI4K2A and PI4K2B are not9. However, although the subcellular localization of PI4K2A and PI4KB is similar (both are mainly Golgi localized), only PI4KB has been reported to be hijacked by viruses. In addition, although the subcellular localization of PI4KA and PI4KB is different (plasma membrane vs Golgi) both enzymes are used by HCV (the preference depends on the HCV genotype).

PI4Ks have been characterized extensively because they are essential host factors for many + RNA viruses9. Crystal structures of all PI4K isoforms except PI4KA are available10–12, their complexes with binding partners Rab11, ACBD3 and 14-3-3 were structurally characterized10,13–15 and potent and extremely selective inhibitors that exert antiviral activity have been developed16–19. PI4Ks are hijacked by viruses either directly or indirectly. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) uses a direct mechanism: its nonstructural NS5A protein directly binds and recruits PI4KA3. Similarly, the nonstructural 3A protein from the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV, genus Cardiovirus) interacts directly with PI4KA20. In contrast, most picornaviruses use an indirect mechanism with several variations among different members of the Picornaviridae family. ACBD3 (acyl-CoA-binding domain-containing protein-3) was recently shown to form a strong complex with PI4KB, activating its lipid kinase activity13,21. Nonstructural 3A proteins from several enteroviruses including poliovirus (PV) and coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) can interact with both guanine nucleotide exchange factor-1 (GBF1)22,23 and ACBD3 simultaneously5,24. Distinct, nonstructural 3A proteins from kobuviruses such as Aichi virus use nearly all their residues to interact with ACBD35,24,25. In addition, genetic ablation of ACBD3 prevents the recruitment of PI4KB to Aichi virus replication sites21. It is important to mention that the picornavirus proteins arise from proteolytical processing of the viral polyprotein in such a way that various stable intermediates such as 3AB or 3CD are generated and that only membrane anchored 3AB is a substrate for the viral 3CD and 3 C protease26 and also that the membrane composition plays a regulatory role27. The poliovirus 3AB protein was previously suggested to anchor the RNA replication complex to the membrane28 through the C-terminal hydrophobic part of the 3A protein29 and the 3AB fusion protein was also previously shown to activate the poliovirus 3Dpol enzyme30. The 3B protein (also known as VPg from viral protein genome linked) arises from the 3AB precursor by cleavage by the proteinase 3CDpro and serves as a primer for the 3Dpol enzyme31.

The reason membranous webs are highly enriched in PI4P is still poorly understood. Picornaviral polymerases are active on their own (without any protein co-factor although a primer, which is the 3B protein in vivo but can be both 3B or nucleic acid in vitro must be present). However, upon assembly of the replication complex their processivity is believed to significantly increase, more details can be found in recent review by OB Peersen32. Another intriguing feature of PI4P is that it can be exchanged for other lipids such as cholesterol33–35 or phosphatidylserine (PS)36 against concentration gradients because PI4P hydrolysis at the target membrane generates energy37. Indeed, production of PI4P to modify the cholesterol content of membranous webs was demonstrated for the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV)20. Another possible function of PI4P could be direct recruitment of viral effector proteins to the replication sites. PI4P binding proteins are well described in several pathogenic bacteria such as the SidC and SidM proteins from Legionella38. 3Dpol could be such a viral factor. If 3Dpol could bind PI4P it would be recruited to replication sites in a PI4P-dependent manner. This mechanism was reported for poliovirus (PV), and PI4P-mediated 3Dpol recruitment was proposed as a mechanism for picornaviral and flaviviral replication39. However, whether PI4P hyper-production is sufficient to recruit the polymerase to the surface of the lipid bilayer is not clear.

Here we sought to directly test the hypothesis that 3Dpol RNA polymerase is recruited to hyper-phosphorylated membranes using a clearly defined in vitro system. We reconstituted the initial generation of membranous web using purified recombinant proteins of the human Aichi virus and the biomimetic giant unilamellar vesicle (GUV) system. GUVs are very large vesicles comparable in size to human cells making them ideal for confocal microscopy. GUVs can also be filled with a sucrose solution which makes them heavier than the surrounding buffer, and as a result they do not move but instead sit at the bottom of the chamber where they are imaged. Additionally, GUVs can be prepared from almost any lipid mixture such that their lipid composition resembles that of the specific organelle they are mimicking (here, we use a mixture resembling the Golgi and viral replication organelles). For these reasons GUVs are used to reconstitute and thereby, gain molecular insight into biologically important processes that involve membranes. For instance, the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) complex catalyzes membrane scission40–42 and GUVs were used to understand this reaction in vitro 43. GUVs were also used to elucidate the mechanism of assembly and ESCRT recruitment by HIV Gag44,45, the clathrin assembly on the surface of GUVs46, and the function of Endophilin-A2 in endocytosis47. Additional examples and practical applications can be found in a recent book on model membranes48.

We chose the human Aichi virus as a model organism because the interaction of its nonstructural 3A protein with host ACBD3 is well described49,50 and reported to be required for the recruitment of PI4KB to the viral replication sites in vivo 21. We demonstrate that the 3A protein is sufficient to facilitate membrane PI-phosphorylation when the appropriate cellular cofactors (ACBD3 and PI4KB) are available. However, although PI4P production alone did not lead to efficient membrane recruitment of 3Dpol, the situation changed when membrane-tethered 3B protein was present. We demonstrate that not only the negatively charged PI4P but another negatively charged lipid, such as PS, can cooperate with membrane-anchored 3B to recruit the 3Dpol enzyme.

Results

3A efficiently recruits ACBD3 to model membranes

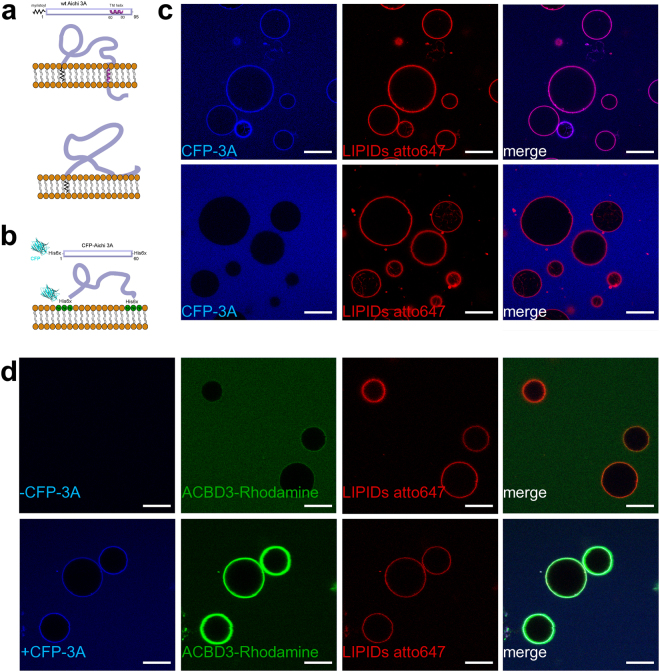

In order to faciliate the recruitment of ACBD3 to model membranes, we engineered a biomimetic recombinant 3A viral protein. The 3A protein is myristoylated at the N-terminal glycine residue24 and also contains a hydrophobic region that every algorithm tested (CCTOP, HMMTOP, MemBrain, Memsat, Octopus, Philius, Phobius, Pro, Prodiv, Scampi, ScampiMsa, and TMHMM) predicts as a transmembrane helix that could anchor 3A protein in the lipid bilayer (Fig. 1A upper panel). This is also supported by our all-atom molecular dynamics simulations of the 3A:GOLD domain complex on the surface of the lipid bilayer49. Alternatively, it was suggested for the poliovirus 3AB protein that this hydrophobic region is semi-buried in the lipid bilayer51 as depicted in the lower panel of Fig. 1A. We fused CFP and a 6xHis tag to the N-terminus of the 3A protein and we replaced the transmembrane helix with another 6xHis tag. The resulting CFP-His6-3A-His6, is tethered by both its N-terminus and C-terminus to a Ni2+ containing membrane in a similar fashion to that of the wild type protein (Fig. 1B). A pilot experiment revealed that the CFP-His6-3A-His6 could be tethered to artificial membranes that contain a nickel cation-bound lipid such as the DGS-NTA(Ni) (Fig. 1C, upper panel) but not to control membranes (Fig. 1C, lower panel).

Figure 1.

Aichi virus 3A protein on the membrane. (A) Schematic representation of the wild type 3A protein. The two possible topologies of the wild type 3A protein are shown. Upper panel – the C-terminal hydrophobic stretch is depicted as a transmembrane helix. Lower panel – the C-terminal hydrophobic stretch is depicted as semi-buried in the lipid bilayer. (B) Schematic representation of the mCerulean - 3A fusion protein (named CFP-3A). CFP-3A contains two 6xHis tags; one between the CFP and its N-terminus and one at the C-terminus. These two His tags can be used to attach the CFP-3A protein to a membrane containing DGS-NTA(Ni) (a lipid that has Ni2+ bound to its headgroup). (C) CFP-3A bound to GUVs. Upper panel: 250 nM CFP-3A was added to GUVs containing 5% of DGS-NTA(Ni) and ATTO647N-DOPE (0.1 mol %). Lower panel: as above but DGS-NTA(Ni) was replaced by POPC. The CFP-3A signal is in blue and the ATTO647 signal in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm. (D) Aichi virus 3A protein efficiently recruits ACBD3 to the membrane. Rhodamine labeled ACBD3 (250 nM) was incubated with GUVs without 3A protein (upper panel) or with 3A protein (250 nM, lower panel). The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the ACBD3-rhodamine signal is in green, and ATTO647 labeled lipids in in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm.

ACBD3 is a Golgi resident scaffolding protein52 that has been reported to interact with 3A proteins from several +RNA viruses including the Aichi virus5,21,24,25,53. We sought to directly test this interaction in vitro and in the context of a membrane. Recombinant ACBD3 labeled with rhodamine was only weakly localized to the membrane at 250 nM concentration (Fig. 1D, upper panel). However, when membranes harbored viral 3A protein, ACBD3 was efficiently recruited to these membranes (Fig. 1D, lower panel).

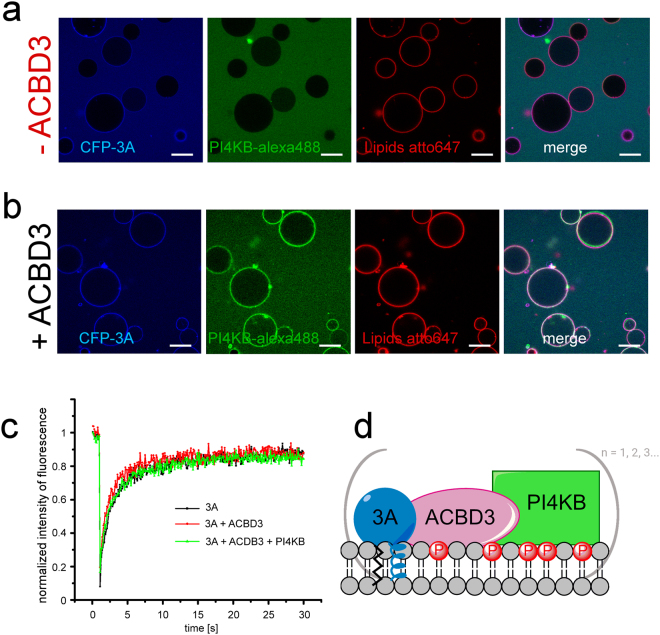

3A, ACBD3, and PI4KB form a protein complex on model membranes

PI4KB is a lipid kinase that must be recruited to membranes to function properly. The interaction of ACBD3 with PI4KB was previously found to have a dissociation constant of 320 nM, and ACBD3 can recruit PI4KB to membranes when ACBD3 is artificially tethered to the membrane surface13. We therefore sought to test if 3A recruited ACBD3 was capable of further recruiting PI4KB to form a larger 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB complex on the membrane. PI4KB is efficiently recruited to model membranes decorated with CFP-3A and ACBD3 (Fig. 2A,B). Next we aimed to elucidate if 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB forms oligomers on the surface of the lipid bilayer. We used fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in which large protein clusters would show significantly slower fluorescence recovery than individual protein complexes54. We compared the FRAP of the CFP-3A, CFP-3A:ACBD3, and CFP-3A:ACBD3:PI4KB (Fig. 2C) and found no statistically significant differences. Based on the fast FRAP we assume that the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex forms a heterotrimer or smaller oligomers on the surface of the membrane but not large assemblies such as lattices that cannot exhibit fast FRAP (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Aichi virus 3A protein recruits the PI4KB kinase via ACBD3. (A) 3A protein does not recruit PI4KB directly to GUVs. 250 nM CFP-3A and PI4KB labeled by Alexa488 were added to GUVs containing 5% of DGS-NTA(Ni) and ATTO647N-DOPE (0.1 mol %). The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the PI4KB-Alexa488 signal is in green and the ATTO647 signal is in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) PI4KB is recruited to membranes when ACBD3 is present. CFP-3A, Alexa488 labeled PI4KB and unlabeled ACBD3 (250 nM each) were added to GUVs containing 5% DGS-NTA(Ni) and ATTO647N-DOPE (0.1 mol %). The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the PI4KB-Alexa488 signal in green and the ATTO647 signal is in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) FRAP analysis of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex. A small cross-section of a GUV membrane was intensively bleached by a 405 nm laser and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of CFP-3A was measured. (D) Schematic representation of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex.

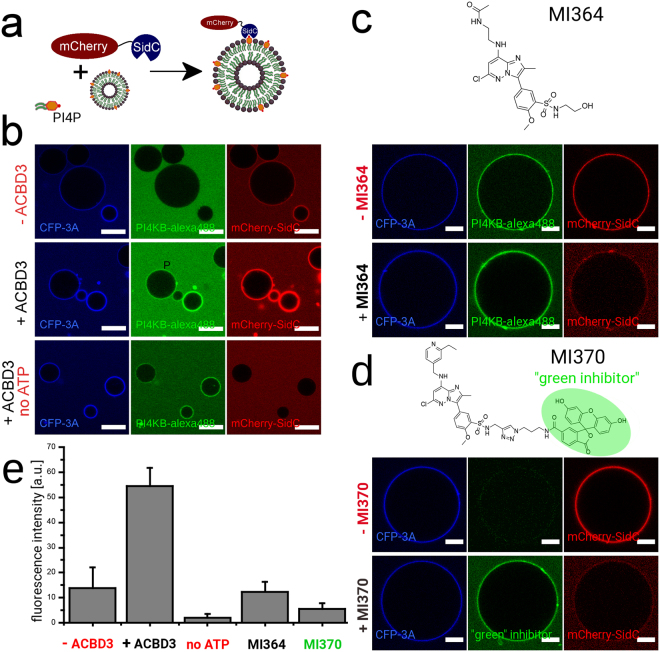

PI4KB is highly active as part of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex

Only membrane-tethered ACBD3 activates the PI4KB enzyme13. It is likely that viruses use their 3A protein to tether the ACBD3 protein to the membrane in order to activate PI4KB21. The 3A protein is perfectly suited for this job because it is membrane tethered and tightly binds ACBD3. To test this hypothesis in vitro we used a SidC fluorescent PI4P biosensor (PI4P binding domain of SidC from Legionella pneumonia fused to mCherry)38 to detect the relative amount of PI4P synthesized on the surface of GUVs (Fig. 3A). GUVs were first decorated with the viral CFP-3A protein and then incubated with PI4KB alone or with ACBD3 and PI4KB (Fig. 3B upper and middle panels). The control consisted of a mixture of all proteins but was devoid of ATP (Fig. 3B lower panel). The efficiency of membrane phosphorylation (the conversion of PI to PI4P) was determined from the biosensor’s fluorescent signal on the surface of the membrane. Background levels of PI4KB lipid phosphorylation in the presence of only the 3A protein decorated GUVs were measured (Fig. 3B upper panel, Fig. 3C). However, the observed efficiency of the reaction in the presence of ACBD3 was far higher as judged by the bio-sensor recruitment (Fig. 3B middle panel). In the absence of ATP, no membrane phosphorylation was observed even when all the proteins were present (Fig. 3B lower panel), documenting the specificity of the system. As an additional control we performed the phosphorylation reaction in the presence of the specific PI4KB inhibitor MI364 (compound 23 in our recent publication55) and, as expected, we observed only limited recruitment of the mCherry-SidC biosensor to the GUVs (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, we performed an analogous experiment using unlabeled PI4KB and a fluorescent PI4KB inhibitor (compound 3 in our recent publication56). Again, we observed only limited recruitment of the mCherry-SidC biosensor. However, in this setting the fluorescent inhibitor could be used to visualize unlabeled PI4KB on the surface of the GUVs (Fig. 3D). Quantification of the fluorescence intensity revealed that the apparent activity of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex was roughly 4-fold higher than that of the PI4KB kinase alone in this system (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

PI4KB is activated in the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex. (A) Scheme of the experiment. A PI4P binding domain from the Legionella pneumonia SidC protein that binds to PI4P with nanomolar affinity was fused to mCherry and used as a fluorescent PI4P biosensor. (B) Production of PI4P on the surface of GUVs. Upper panel: GUVs decorated with the viral 3A-CFP protein (250 nM) were incubated with Alexa488 labeled PI4KB (250 nM) and SidC-mCherry (100 nM) and imaged using a confocal microscope. Middle panel: As above but also ACBD3 (250 nM) was also added. Lower panel: As the middle panel but no ATP was added. The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the PI4KB-Alexa488 signal in green and the mCherry-SidC signal is in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) Inhibition by the compound MI364. On the top is the chemical structure of MI364. On the bottom is a representative image of GUVs phosphorylated by Alexa488 labeled PI4KB (upper panel: without MI364, lower panel: with 5 µM MI364). The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the PI4KB-Alexa488 signal in green and the mCherry-SidC signal is in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Inhibition by the fluorescent compound MI370. On the top is the chemical structure of MI370 (the fluorescent part in highlighted in green). On the bottom is a representative image of GUVs phosphorylated by unlabeled PI4KB (upper panel: without MI370, lower panel: with 5 µM MI370). The CFP-3A signal is in blue, the MI370 signal in green and the mCherry-SidC signal is in red. Representative image of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 10 µm. (E) Quantification of PI4P production. Quantification of the intensity of fluorescence of the SidC-mCherry PI4P biosensor on the surface of GUVs was. Standard deviations are based on three independent experiments.

PI4P and Aichi 3Dpol membrane recruitment

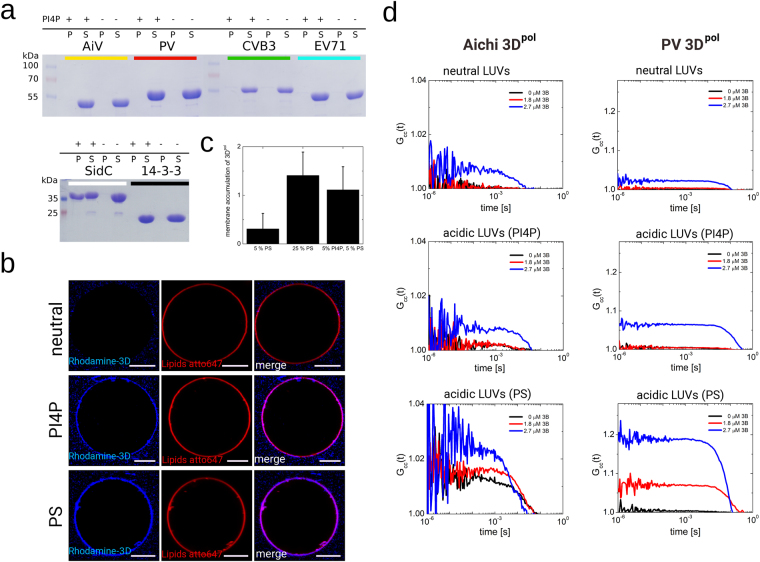

The reconstitution of ACBD3 recruitment to model membranes by viral 3A, and the subsequent recruitment of the lipid kinase PI4KB made possible the analysis of the membranes binding properties of 3Dpol. We used our in vitro GUV system to test PI4P mediated 3Dpol recruitment because this mechanism was suggested previously39. As shown above, the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB complex efficiently phosphorylates GUVs to make PI4P (Fig. 3). However, we did not observe 3Dpol membranes recruitment even though the mCherry-SidC nanomolar PI4P binder biosensor was recruited (SI Fig. 1A). Similarly, 3Dpol failed to bind GUVs prepared with synthetic PI4P (SI Fig. 1B). We reasoned that the 3Dpol:PI4P interaction might be weak, or that the Aichi 3Dpol is unique among 3Dpol enzymes in that it does not bind PI4P. Therefore, we tested several different 3Dpol enzymes (Aichi virus, PV, CVB3, EV71) in a liposome pulldown assay. However, no PI4P-mediated liposome binding of any of the polymerases was detected using this method (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

3Dpol enzymes efficiently bind acidic membranes only in the presence of membrane-tethered 3B. (A) Recombinant 3Dpol enzymes from several +RNA viruses bind PI4P poorly in a liposome pulldown assay. 3Dpol from the Aichi virus (AiV), Polio virus (PV), Coxsackie virus B3 (CVB3) and Enterovirus 71 (EV71) show no binding to PI4P liposomes at 60 µM concentration. SidC was used as a positive control and 14-3-3ζ protein as a negative control. Liposomes were centrifuged and the pellets (denoted P) and supernatants (denoted S) were analyzed using SDS PAGE. For the full length gels see the SI Fig. 2. (B) GUV recruitment assay. GUVs of different composition were used. Upper panel – neutral membrane (5% PS), middle panel – PI4P acidic membrane (5% PS + 5% PI4P), lower panel – PS acidic membrane. Aichi 3Dpol fluorescence signal in blue (left), membrane in red (middle) and merged image (right). A typical result of three independent experiments. Scale bar = 20 µm. (C) Quantification of Aichi 3Dpol binding to membranes of different composition. Composition dependent membrane accumulation of CFP-3Dpol: excess of the fluorescence signal of CFP in the GUV pixels relative to the signal of unbound CFP-3Dpol. The error bars indicate a 95% confidence interval. (D) Cros-scorrelation curves of CFP – 3Dpol and LUVs. FCS curves representing temporal cross-correlation of the CFP-3Dpol (Aichi 3Dpol on the left panel and PV 3Dpol on the right panel) and ATTO647N-DOPE labelled LUVs at various membrane lipid compositions (neutral, enriched by PI4P, and enriched by PS; see SI Table 1). The curves show the cooperative effect of the 3B peptide on 3Dpol membrane recruitment. The concentration of the Aichi or PV 3B peptide (attached to the membrane surface by His-tag – 18:1 DGS-NTA(Ni) interaction) was 0 µM (black), 1.8 µM (red), and 2.7 µM (blue).

Pulldown assays are not sensitive and a weak but biologically relevant interaction could be overlooked. Therefore, we performed a more sensitive experiment. GUVs were incubated with fluorescently (rhodamine) labeled Aichi 3Dpol at nanomolar concentration, which facilitates efficient binding due to the vast excess of lipids. In addition, the fluorescence image was taken using a low scanner speed (50 µs per pixel) to ensure a higher signal-to-noise ratio (Fig. 4B). We used GUVs with PI4P and two sets of controls: neutral GUVs in which PI4P was replaced with the neutral lipid PC and an acidic membrane where PI4P was replaced with the negatively charged PS lipid (we used four molecules of PS for every molecule of PI4P to create a highly acidic membrane without the PI4P lipid). We observed that 3Dpol does not bind to neutral GUVs (Fig. 4B upper panel). However, 3Dpol did bind the PI4P-containing GUVs (Fig. 4B middle panel) suggesting that the 3Dpol enzyme is, indeed, capable of binding PI4P containing membranes albeit with low affinity. Surprisingly, the 3Dpol enzyme could also bind PS-containing acidic GUVs (Fig. 4B lower panel). Quantification of membrane binding revealed that 3Dpol enzyme binds acidic GUVs without a preference for specific acidic lipids (Fig. 4C).

However, the extent of 3Dpol recruitment by model acidic membranes seems too low to support efficient viral replication within the host cell. The only other reported binding partner of any 3Dpol enzyme (besides the RNA) is the small 3B protein that serves as a primer. A portion of 3B in the infected cell exists as a membrane tethered 3AB fusion protein. Thus, we used our in vitro system to test whether membrane-tethered 3B and the acidic membrane can cooperate to recruit 3Dpol enzymes. We could not use GUVs for this experiment because the reported dissociation constants between 3B and 3D are in the tens of micromolar range and it is not possible to use micromolar lipid concentrations in the case of GUVs. We instead used large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs). Aichi and poliovirus (PV) 3Dpol enzymes were incubated with LUVs in the presence of increasing concentrations of membrane-tethered 3B proteins, and the temporal fluorescence cross-correlation function between the CFP labeled 3Dpol and ATTO647N labeled LUVs was measured. In this analysis, the higher the cross-correlation the higher the binding (Fig. 4D, SI Fig. 4). We observed negligible binding of Aichi 3Dpol to neutral membranes at all 3B concentrations tested (0–2.7 µM) and small PV 3Dpol binding to neutral membranes at high membrane-tethered 3B concentrations. However, 3Dpol binding to acidic membranes (PI4P or PS) increased with increasing concentrations of membrane tethered 3B.

Discussion

PI4P production is essential for many + RNA viruses, however, + RNA viruses do not encode PI4K enzymes and must hijack human enzymes. Many viruses including the Aichi virus converged on hijacking the PI4KB enzyme through the interaction with the ACBD3 protein. We recently showed that ACBD3 is a sub-micromolar binder of PI4KB and that ACBD3 can recruit the PI4KB enzyme to any membrane both in vitro and in vivo 13. Because the viral 3A protein is a transmembrane protein that tightly binds the GOLD domain of ACBD349, it can recruit ACBD3 and thus the PI4KB to any target membrane. Soon after formation of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex, the membranes become hyper-phosphorylated, which is a key step in the biogenesis of replication organelles - a complex process that is not fully understood. It is initiated after polyprotein synthesis followed by stepwise proteolytic cleavage by viral proteases. These cleavage events produce intermediate as well as final cleavage products that together with host factors initiate replication complex formation. One of them is the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex.

Here we reconstituted in vitro the formation of the 3A:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex and membrane phosphorylation. We first prepared fluorescently labeled Aichi 3A protein and tethered it to the surface of GUVs to mimic infected cells (Fig. 1). As expected, the membrane-tethered 3A protein was able to recruit ACBD3 and subsequently the PI4KB kinase to the model membranes. Thus, our in vitro reconstitution experiments show that the small 3A protein is sufficient to recruit and activate PI4KB through interaction with ACBD3. This is an elegant mechanism – a protein less than 100 amino acids is all that is needed for the membrane hyper-phosphorylation – a key step of replication organelles formation. Congruently, when our manuscript was under review another study was published that also shows that viral 3A protein can activate PI4KB through the ACBD3 protein50.

The next key step in replication factory biogenesis is the recruitment of the viral 3Dpol enzyme. It was suggested that the 3Dpol enzyme binds directly to the PI4P lipid39. Therefore, we decided to reconstitute 3Dpol recruitment using our in vitro system. We did not observe 3Dpol recruitment to membranes under conditions in which the nanomolar PI4P reported was clearly recruited (SI Fig. 1). However, we did observe 3Dpol recruitment to PI4P rich membranes using a more sensitive technique (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, 3Dpol was also recruited to negative charged PS-containing membranes but not to neutral membranes (Fig. 4B). We repeated all experiments using the poliovirus 3Dpol enzyme to rule out the possibility that this mechanism is specific for the Aichi 3Dpol enzyme. Similar results were obtained, indicating that the 3B protein is crucial in recruitment of the 3Dpol enzymes. The PV 3B protein could somewhat recruit to neutral membranes while the Aichi 3B protein could not, but recruitment was more efficient in the context of negatively charged membranes. It is also worth mentioning, that we observed a somewhat lower cooperativity effect of the poliovirus 3B and 3Dpol proteins at the negatively charged membranes as documented by the lower amplitude of the cross-correlation function (SI Fig. 3). However, poliovirus 3Dpol is known to be able to form multimers57,58 and the avidity effect probably more than compensates. Interestingly, the PS lipid was significantly better in recruitment of the Aichi 3Dpol enzyme while in the case of the PV 3Dpol PS performed only slightly better than PI4P (Fig. 4D) which further supports our hypothesis that PI4P is not specifically recognized by picornaviral 3Dpol enzymes.

Many human and animal +RNA viruses including poliovirus (PV), Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), rhinovirus, norovirus, and HCV target the ER, Golgi or TGN membranes highly enriched in PI4P and cholesterol59. However, the observed interaction of 3Dpol enzymes with a properly (negatively) charged cholesterol rich model membrane is rather weak. Importantly, 3Dpol is a part of a relatively stable precursor protein that could affect its membrane recruitment in infected cells. The 3 CDpro precursor protein of poliovirus is stable enough to be analyzed by protein crystallography60. The putative function of 3Dpol in the 3 CDpro protein is to modulate the proteolytic activity of the 3C protease domain and RNA binding of the 3CDpro protein32. It is important to emphasize that the picornaviral 3CDpro has no polymerase activity. It only becomes active upon proteolytic cleavage of the link between the 3C and 3D proteins32.

As with most polymerases, 3Dpol requires a primer. While in vitro it can initiate RNA synthesis using an RNA or DNA primer in vivo the viral 3B protein is always used as a primer and the first step is uridylylation of its tyrosine side chain61. The viral 3B protein is partially present as a membrane-tethered 3AB fusion protein and it was previously suggested to serve as a tether for 3Dpol in vivo 28,62. In our in vitro system, the membrane tethered 3B protein increased the efficiency of 3Dpol recruitment (Fig. 4D, SI Fig. 4). We conclude that negative charge and the membrane-tethered 3B protein work in combination to recruit 3Dpol enzymes. We thus propose that two protein complexes-3A:ACBD3:PI4KB (Fig. 2D) and 3Dpol:3AB:ACBD3:PI4KB (Fig. 5) - are in a dynamic equilibrium in infected cells. While both are PI-phosphorylation competent only the latter also participates in RNA synthesis.

Figure 5.

Schematic model of the 3Dpol:3AB:ACBD3:PI4KB protein complex.

Concluding Remarks

In vitro reconstitution is a powerful tool for testing biological hypotheses. The hypothesis that the non-structural 3A protein is the only viral protein needed to hyper-phosphorylate membranes when the cellular co-factors are present was proven in our in vitro system. However, our bio-mimetic GUV system reconstitution revealed that negative charged lipids and not necessarily PI4P are responsible for recruitment of the 3Dpol enzyme to the surface of the lipid bilayer. Moreover, our studies also revealed that the 3B protein works in combination with the negative charge to efficiently recruit the 3Dpol enzyme.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, Protein Expression and Purification

ACBD3, PI4KB (with deleted disordered loop 424–521 to increase stability and to facilitate bacterial expression), and mCherry-SidC (PI4P binding domains only, amino acid residues 613–742) were expressed as described previously15. AiV, EV 71, CVB3 3Dpol were cloned into the pRSFD vector with a His6-GB1 purification/solubility tag at the N-terminus followed by a TEV protease cleavage site. PV 3Dpol was expressed from the plasmid pCG1. This plasmid contains a ubiquitin tag at the N-terminus and His6 purification tag at the C-terminus of the PV 3Dpol. To remove the ubiquitin tag and generate PV 3Dpol with a native N-terminus, the PV 3Dpol was co-expressed with ubiquitin protease in E. coli and further purified as previously described63. CFP-3A protein was cloned into a pRSFD vector with a His6 purification tag at the N-terminus followed by a TEV cleavage site and a mCerulean fluorescent protein (CFP) to produce final protein His6-TEV-CFP-His-Aichi 3A (residues 1–58)-His6. CFP-3Dpol proteins were cloned into pRSFD vector with a His6 purification tag at the N-terminus followed by a TEV cleavage site and mCerulean fluorescent protein to produce the final protein His6-TEV-CFP-3Dpol. These proteins were purified using standard protocols in our laboratory64,65. Briefly, the proteins were expressed in BL21 Stars cells grown in autoinduction media at 18 °C overnight. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 3 mM βME, 10% glycerol) and nickel affinity purification was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Machery-Nagel). The His6 and His6-GB1 tags were removed by the TEV protease. The CFP-3A protein was prone to degradation, however, degradation products were removed by anion exchange chromatography. Finally, proteins were purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) in SEC buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 3 mM βME or 0.2 mM TCEP if the protein was meant to be labeled), concentrated to 3–10 mg/ml, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until needed.

Protein labeling with fluorescent dyes

ACBD3, 3Dpol and PI4KB were labeled on native cysteine residues as described previously13. Briefly, a 3-fold molar excess of rhodamine or Alexa488 maleimide derivatives (Molecular Probes) was incubated with pure recombinant proteins at 4 °C overnight. The reaction was quenched by adding a large molar excess of βME and the proteins were purified again on SEC. Labeling efficiency was estimated spectroscopically to be 116% for PI4KB labeled with Alexa488, 250% for 3Dpol labeled with rhodamine and 181% for ACBD3 labeled with rhodamine.

Giant Unilamellar Vesicle Preparation and Imaging

Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) were composed of POPC (54.9 mol %), POPS (5 or 10 mol %), PI4P (0 or 5 mol %) cholesterol (20 mol %), PI (10 mol %), DGS-NTA(Ni) (0 or 5 mol %) (Avanti Polar lipids), and ATTO647N-DOPE (0.1 mol %). Membrane composition for each experiment is also summarized in SI Table 1. When changing the concentration of the lipid mixture (e.g. to contain or not to contain PI4P or DGS-NTA(Ni)), charged lipids were always replaced with charged lipids (POPS for PI4P) and non-polar lipids with non-polar lipids (DGS-NTA(Ni) for POPC) to keep the net charge the same throughout all the experiments. GUVs were prepared by electroformation in a homemade teflon chamber as described previously66. Briefly, 50 µg of the lipid mixture in 10 µl volume was spread onto each ITO coated glass (5 × 5 cm) and dried under vacuum overnight. Later the glasses were placed in the teflon chamber separated by 1 mm thick spacers and 5 ml of 600 mM sucrose preheated to 60° was added and AC current (10 Hz, maximum amplitude 1 V) was applied for one hour in an incubator warmed to 60°. Then the chamber was allowed to cool down to room temperature and the GUVs were transferred with a glass pipette to a glass test tube. For imaging 100 µl of the GUVs were mixed with 100 µl of isotonic buffer (90 mM Tris pH 8, 20 mM MgCl2, 40 mM Imidazole, 565 mM NaCl, 3 mM βME) in a BSA coated 4-chamber glass bottom dish (In Vitro Scientific). GUVs were imaged using the filterless Zeiss LSM780 confocal system. To avoid bleed-through only mCerulean (CFP) tagged proteins (excitation 405 nm, emission 465–571 nm) and ATTO647-tagged lipids (excitation 633 nm, emission 645–759 nm) were excited simultaneously. Alexa488 (excitation 488, emission 508–578 nm), Rhodamine (excitation 561 nm, emission 565–585 nm) and mCherry (excitation 561 nm, emission 604–621 nm) fluorophores were excited separately. Images were processed using the ZEN 2012 software (Zeiss) and ImageJ67.

Liposome (MLVs and LUVs) preparation

To prepare MLVs (multilamellar large vesicles) 1 mg of lipids composed of POPC (60 mol %), POPS (10 mol %), PI4P (10 mol %), and cholesterol (20 mol %) was mixed in chloroform. The chloroform was evaporated over a stream of dry nitrogen and the lipids were further dried under vacuum for at least three hours. Then the lipid film was rehydrated with 1 mL of liposome buffer (10 mM Tris pH = 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM βME) and vortexed intensively. To obtain LUVs (large unilamellar vesicles) the turbid solution containing MLVs was extruded 21 times using 100 nm filters in the extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc, Alabaster, AL, U.S.A.).

Liposome pulldown assay

Liposome pulldown assays were performed as described previously68. Briefly, MLVs with and without PI4P were prepared as described above. The liposomes were incubated with: AiV, PV, CVB3 and EV71 3Dpol enzymes (final protein concentration 60 μM and final lipid concentration 0.5 mg/ml) in a total volume of 60 μl. SidC (KD towards PI4P = 70 nM38) was used as a positive control (15 μM) and 14-3-3ζ (30 μM) was used as a negative control. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 20 min on ice. The mixtures were then centrifuged (22000 g, 10 min). The supernatant was removed and the pellet re-suspended in 60 μl of liposome buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM βME) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Control liposomes with no PI4P were used to confirm that binding was due to PI4P.

Fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCCS)

The FCCS experiments were carried out at LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with an LSM upgrade kit (Picoquant, Berlin, Germany) enabling Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) acquisition. CFP and ATTO647N was excited by a 405 nm laser at 20 MHz repetition frequency, and by a 633 nm continuous-wave laser, respectively. A 40x/1.2 water objective was used together with a pinhole in the detection plain. Behind the pinhole, light was guided to the detectors (tau-SPADs, Picoquant), in front of which the emission filters (482/35, and 650/50) were placed. The collected data were correlated using a home-written script in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) according to the algorithm described in69. To avoid detector crosstalk, the red channel fluorescence signal was split according to its TCSPC pattern (exponential for the signal generated by the pulsed laser and flat for the 633 nm continuous wave laser) into two contributions and only the signal assigned to the flat TCSPC profile was correlated. Details of data processing are given in Gregor and Enderlein70.

50 µL of LUVs were mixed with 1 µL of CFP-3Dpol (100 nM), 0–20 µL of 3B-His (18 µM), and the LUV buffer, so that the final volume was 100 µL, the concentration of CFP-3Dpol was 1 nM, and the concentration of 3B-His ranged from 0 to 2.7 µM. The FCS experiment was carried out 15–20 minutes after mixing.

The lipid composition of LUVs is summarized in SI Table 1. Briefly: (POPC (64.99-x-y %), POPS (x%), PI4P (y%), PI (10%), cholesterol (20%), DGS-NTA(Ni) (5%), ATTO647N-DOPE (0.01%), where x = 0 and y = 0 for neutral membranes, x = 10 and y = 5 for acidic, PI4P-containing membranes, and x = 25% and y = 0% for acidic, highly charged membranes.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation grant number 15–21030Y. The Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic (RVO: 61388963) is also acknowledged. We are grateful to Prof. Joseph DeRisi (UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA) for sharing the synthetic Aichi virus genome, to Prof. Carolyn Machamer (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) for sharing the ACBD3 encoding plasmid and to Prof. O. Peersen (Colorado State University) for sharing the pCG1 expression plasmid. We are also grateful to Dr. Edward Curtis for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

A.D., J.H. and M.K. performed experiments. E.B. designed and supervised the project. E.B. wrote the manuscript, all authors contributed to data analysis and commented on the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Anna Dubankova and Jana Humpolickova contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-017-17621-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.den Boon JA, Ahlquist P. Organelle-like membrane compartmentalization of positive-strand RNA virus replication factories. Annual review of microbiology. 2010;64:241–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger KL, et al. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902693106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger KL, Kelly SM, Jordan TX, Tartell MA, Randall G. Hepatitis C virus stimulates the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha-dependent phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate production that is essential for its replication. Journal of virology. 2011;85:8870–8883. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00059-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arita M, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta is a target of enviroxime-like compounds for antipoliovirus activity. Journal of virology. 2011;85:2364–2372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02249-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki J, Ishikawa K, Arita M, Taniguchi K. ACBD3-mediated recruitment of PI4KB to picornavirus RNA replication sites. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:754–766. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiss S, et al. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell host & microbe. 2011;9:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dornan GL, McPhail JA, Burke JE. Type III phosphatidylinositol 4 kinases: structure, function, regulation, signalling and involvement in disease. Biochemical Society transactions. 2016;44:260–266. doi: 10.1042/BST20150219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boura E, Nencka R. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases: Function, structure, and inhibition. Experimental cell research. 2015;337:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altan-Bonnet N, Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases: hostages harnessed to build panviral replication platforms. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2012;37:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke JE, et al. Structures of PI4KIIIbeta complexes show simultaneous recruitment of Rab11 and its effectors. Science. 2014;344:1035–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1253397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumlova A, et al. The crystal structure of the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIalpha. EMBO reports. 2014;15:1085–1092. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klima M, et al. The high-resolution crystal structure of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIbeta and the crystal structure of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIalpha containing a nucleoside analogue provide a structural basis for isoform-specific inhibitor design. Acta crystallographica. Section D, Biological crystallography. 2015;71:1555–1563. doi: 10.1107/S1399004715009505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klima M, et al. Structural insights and in vitro reconstitution of membrane targeting and activation of human PI4KB by the ACBD3 protein. Scientific reports. 2016;6:23641. doi: 10.1038/srep23641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenreichova A, Klima M, Boura E. Crystal structures of a yeast 14-3-3 protein from Lachancea thermotolerans in the unliganded form and bound to a human lipid kinase PI4KB-derived peptide reveal high evolutionary conservation. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2016;72:799–803. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X16015053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalupska, D. et al. Structural analysis of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIbeta (PI4KB) - 14-3-3 protein complex reveals internal flexibility and explains 14-3-3 mediated protection from degradation in vitro. Journal of structural biology, 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.08.006 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lamarche MJ, et al. Anti-hepatitis C virus activity and toxicity of type III phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase beta inhibitors. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2012;56:5149–5156. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00946-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raubo P, et al. Discovery of potent, selective small molecule inhibitors of alpha-subtype of type III phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase (PI4KIIIalpha) Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2015;25:3189–3193. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mejdrova I, et al. Highly Selective Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIbeta Inhibitors and Structural Insight into Their Mode of Action. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2015;58:3767–3793. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutaganira FU, et al. Design and Structural Characterization of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Phosphatidylinositol 4 Kinase IIIbeta. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2016;59:1830–1839. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorobantu, C. M. et al. Modulation of the Host Lipid Landscape to Promote RNA Virus Replication: The Picornavirus Encephalomyocarditis Virus Converges on the Pathway Used by Hepatitis C Virus. PLoS pathogens11, doi:ARTN e100518510.1371/journal.ppat.1005185 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ishikawa-Sasaki K, Sasaki J, Taniguchi K. A complex comprising phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIbeta, ACBD3, and Aichi virus proteins enhances phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate synthesis and is critical for formation of the viral replication complex. Journal of virology. 2014;88:6586–6598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00208-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wessels E, et al. A viral protein that blocks Arf1-mediated COP-I assembly by inhibiting the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Developmental cell. 2006;11:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wessels E, et al. Molecular determinants of the interaction between coxsackievirus protein 3A and guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Journal of virology. 2007;81:5238–5245. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02680-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greninger AL, Knudsen GM, Betegon M, Burlingame AL, Derisi JL. The 3A protein from multiple picornaviruses utilizes the golgi adaptor protein ACBD3 to recruit PI4KIIIbeta. Journal of virology. 2012;86:3605–3616. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06778-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greninger AL, Knudsen GM, Betegon M, Burlingame AL, DeRisi JL. ACBD3 interaction with TBC1 domain 22 protein is differentially affected by enteroviral and kobuviral 3A protein binding. mBio. 2013;4:e00098–00013. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00098-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lama J, Paul AV, Harris KS, Wimmer E. Properties of purified recombinant poliovirus protein 3aB as substrate for viral proteinases and as co-factor for RNA polymerase 3Dpol. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arita M. Mechanism of Poliovirus Resistance to Host Phosphatidylinositol-4 Kinase III beta Inhibitor. ACS Infect Dis. 2016;2:140–148. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyle JM, et al. Similar structural basis for membrane localization and protein priming by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:16324–16331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita K, et al. Membrane topography of the hydrophobic anchor sequence of poliovirus 3A and 3AB proteins and the functional effect of 3A/3AB membrane association upon RNA replication. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5185–5199. doi: 10.1021/bi6024758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plotch SJ, Palant O. Poliovirus protein 3AB forms a complex with and stimulates the activity of the viral RNA polymerase, 3Dpol. Journal of virology. 1995;69:7169–7179. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7169-7179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paul AV, van Boom JH, Filippov D, Wimmer E. Protein-primed RNA synthesis by purified poliovirus RNA polymerase. Nature. 1998;393:280–284. doi: 10.1038/30529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peersen OB. Picornaviral polymerase structure, function, and fidelity modulation. Virus research. 2017;234:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong J, Yang H, Yang H, Eom SH, Im YJ. Structure of Osh3 reveals a conserved mode of phosphoinositide binding in oxysterol-binding proteins. Structure. 2013;21:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita M. Phosphatidylinositol-4 kinase III beta and oxysterol-binding protein accumulate unesterified cholesterol on poliovirus-induced membrane structure. Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58:239–256. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roulin PS, et al. Rhinovirus uses a phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate/cholesterol counter-current for the formation of replication compartments at the ER-Golgi interface. Cell host & microbe. 2014;16:677–690. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung J, et al. Intracellular Transport. PI4P/phosphatidylserine countertransport at ORP5- and ORP8-mediated ER-plasma membrane contacts. Science. 2015;349:428–432. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser von Filseck J, Vanni S, Mesmin B, Antonny B, Drin G. A phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate powered exchange mechanism to create a lipid gradient between membranes. Nature communications. 2015;6:6671. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dolinsky S, et al. The Legionella longbeachae Icm/Dot substrate SidC selectively binds phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate with nanomolar affinity and promotes pathogen vacuole-endoplasmic reticulum interactions. Infection and immunity. 2014;82:4021–4033. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01685-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu NY, et al. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell. 2010;141:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurley JH, Boura E, Carlson LA, Rozycki B. Membrane budding. Cell. 2010;143:875–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCullough J, Colf LA, Sundquist WI. Membrane fission reactions of the mammalian ESCRT pathway. Annual review of biochemistry. 2013;82:663–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072909-101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rozycki B, Boura E, Hurley JH, Hummer G. Membrane-elasticity model of Coatless vesicle budding induced by ESCRT complexes. PLoS computational biology. 2012;8:e1002736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wollert T, Wunder C, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hurley JH. Membrane scission by the ESCRT-III complex. Nature. 2009;458:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature07836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson LA, Hurley JH. In vitro reconstitution of the ordered assembly of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport at membrane-bound HIV-1 Gag clusters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:16928–16933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211759109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson, L. A., Bai, Y., Keane, S. C., Doudna, J. A. & Hurley, J. H. Reconstitution of selective HIV-1 RNA packaging in vitro by membrane-bound Gag assemblies. eLife5, 10.7554/eLife.14663 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Saleem M, et al. A balance between membrane elasticity and polymerization energy sets the shape of spherical clathrin coats. Nature communications. 2015;6:6249. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renard HF, et al. Endophilin-A2 functions in membrane scission in clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nature. 2015;517:493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature14064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pabst, G., Kucerka, N., Nieh, M. P. & Katsaras, J. Liposomes, Lipid Bilayers and ModelMembranes From Basic Research to Application Preface. Liposomes, Lipid Bilayers and Model Membranes: From Basic Research to Application, Ix–X, 10.1201/b16617 (2014).

- 49.Klima M, et al. Kobuviral Non-structural 3A Proteins Act as Molecular Harnesses to Hijack the Host ACBD3 Protein. Structure. 2017;25:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McPhail JA, Ottosen EH, Jenkins ML, Burke JE. The Molecular Basis of Aichi Virus 3A Protein Activation of Phosphatidylinositol 4 Kinase IIIbeta, PI4KB, through ACBD3. Structure. 2017;25:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Ptacek JB, Kirkegaard K, Bullitt E. Double-membraned liposomes sculpted by poliovirus 3AB protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:27287–27298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.498899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan J, Liu J, Culty M, Papadopoulos V. Acyl-coenzyme A binding domain containing 3 (ACBD3; PAP7; GCP60): an emerging signaling molecule. Progress in lipid research. 2010;49:218–234. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teoule F, et al. The Golgi protein ACBD3, an interactor for poliovirus protein 3A, modulates poliovirus replication. Journal of virology. 2013;87:11031–11046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00304-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wollert T, Hurley JH. Molecular mechanism of multivesicular body biogenesis by ESCRT complexes. Nature. 2010;464:864–869. doi: 10.1038/nature08849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mejdrova I, et al. Rational Design of Novel Highly Potent and Selective Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIbeta (PI4KB) Inhibitors as Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agents and Tools for Chemical Biology. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2017;60:100–118. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Humpolickova J, Mejdrova I, Matousova M, Nencka R, Boura E. Fluorescent Inhibitors as Tools To Characterize Enzymes: Case Study of the Lipid Kinase Phosphatidylinositol 4-Kinase IIIbeta (PI4KB) Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2017;60:119–127. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spagnolo JF, Rossignol E, Bullitt E, Kirkegaard K. Enzymatic and nonenzymatic functions of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases within oligomeric arrays. Rna. 2010;16:382–393. doi: 10.1261/rna.1955410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pathak HB, Arnold JJ, Wiegand PN, Hargittai MR, Cameron CE. Picornavirus genome replication: assembly and organization of the VPg uridylylation ribonucleoprotein (initiation) complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:16202–16213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610608200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altan-Bonnet N. Lipid Tales of Viral Replication and Transmission. Trends in cell biology. 2017;27:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marcotte LL, et al. Crystal structure of poliovirus 3CD protein: virally encoded protease and precursor to the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Journal of virology. 2007;81:3583–3596. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02306-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paul AV, Rieder E, Kim DW, van Boom JH, Wimmer E. Identification of an RNA hairpin in poliovirus RNA that serves as the primary template in the in vitro uridylylation of VPg. Journal of virology. 2000;74:10359–10370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.22.10359-10370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hope DA, Diamond SE, Kirkegaard K. Genetic dissection of interaction between poliovirus 3D polymerase and viral protein 3AB. Journal of virology. 1997;71:9490–9498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9490-9498.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong P, Kortus MG, Nix JC, Davis RE, Peersen OB. Structures of coxsackievirus, rhinovirus, and poliovirus polymerase elongation complexes solved by engineering RNA mediated crystal contacts. PloS one. 2013;8:e60272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nemecek D, et al. Subunit folds and maturation pathway of a dsRNA virus capsid. Structure. 2013;21:1374–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rezabkova L, et al. 14-3-3 protein interacts with and affects the structure of RGS domain of regulator of G protein signaling 3 (RGS3) Journal of structural biology. 2010;170:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boura E, Ivanov V, Carlson LA, Mizuuchi K, Hurley JH. Endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) complexes induce phase-separated microdomains in supported lipid bilayers. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:28144–28151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schindelin J, Rueden CT, Hiner MC, Eliceiri KW. The ImageJ ecosystem: An open platform for biomedical image analysis. Molecular reproduction and development. 2015;82:518–529. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boura E, Hurley JH. Structural basis for membrane targeting by the MVB12-associated beta-prism domain of the human ESCRT-I MVB12 subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:1901–1906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117597109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wahl M, Gregor I, Patting M, Enderlein J. Fast calculation of fluorescence correlation data with asynchronous time-correlated single-photon counting. Optics express. 2003;11:3583–3591. doi: 10.1364/OE.11.003583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gregor I, Enderlein J. Time-resolved methods in biophysics. 3. Fluorescence lifetime correlation spectroscopy. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2007;6:13–18. doi: 10.1039/B610310C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.