Abstract

Bacterial secondary metabolites possess a wide range of biologically active compounds including antibacterial and antioxidants. In this study, a Gram-positive novel marine Actinobacteria was isolated from sea sediment which showed 84% 16S rRNA gene sequence (KT588655) similarity with Streptomyces variabilis (EU841661) and designated as Streptomyces variabilis RD-5. The genus Streptomyces is considered as a promising source of bioactive secondary metabolites. The isolated novel bacterial strain was characterized by antibacterial characteristics and antioxidant activities. The BIOLOG based analysis suggested that S. variabilis RD-5 utilized a wide range of substrates compared to the reference strain. The result is further supported by statistical analysis such as AWCD (average well color development), heat-map and PCA (principal component analysis). The whole cell fatty acid profiling showed the dominance of iso/anteiso branched C15–C17 long chain fatty acids. The identified strain S. variabilis RD-5 exhibited a broad spectrum of antibacterial activities for the Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli NCIM 2065, Shigella boydii NCIM, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas sp. NCIM 2200 and Salmonella enteritidis NCIM), and Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2920 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96). Extract of S. variabilis strain RD-5 showed 82.86 and 89% of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging and metal chelating activity, respectively, at 5.0 mg/mL. While H2O2 scavenging activity was 74.5% at 0.05 mg/mL concentration. Furthermore, polyketide synthases (PKSs types I and II), an enzyme complex that produces polyketides, the encoding gene(s) detected in the strain RD-5 which may probably involve for the synthesis of antibacterial compound(s). In conclusion, a novel bacterial strain of Actinobacteria, isolated from the unexplored sea sediment of Alang, Gulf of Khambhat (Gujarat), India showed promising antibacterial activities. However, fractionation and further characterization of active compounds from S. variabilis RD-5 are needed for their optimum utilization toward antibacterial purposes.

Keywords: Actinobacteria, antibacterial, antioxidant, biolog, marine bacteria, novel strain, polyketide synthases, sea sediment

Introduction

More than 70% of the surface of the earth planet covers by the sea which contains exceptional diversity which is more than 95% of the whole biosphere (Qasim, 1999). It was observed that the living diversity is higher in some marine ecosystems, such as the deep sea and coral reefs, than the tropical rainforests (Edwards et al., 2006). The ocean is the habitat of several groups of life-forms which live in a complex environment with extreme variations in pressure, salinity, light, and temperature (Munn, 2004). Recently, it was proven that the ocean floor possesses many unique forms of Actinobacteria (Fenical and Jensen, 2006). Actinobacteria are widely distributed in intertidal zones, mangroves, seawaters, animals, plants, sponges, and in ocean sediments (Goodfellow and Williams, 1983; Castillo et al., 2005; Jensen and Mafnas, 2006; Ramesh and Mathivanan, 2009; Sun et al., 2010; Xiao et al., 2011; Rao and Rao, 2013). Actinobacteria from the marine environment are considered as a promising source of pharmaceutically important compounds because of a different kind of unique adaptation characteristics (Fenical and Jensen, 2006; Jose and Jha, 2017).

Actinobacteria are Gram-positive bacteria with filamentous structure. These are considered the most economical and biotechnological important prokaryotes which produce several secondary metabolites with significant biological activities. Out of these Actinobacteria, Streptomyces is an important industrial group of organisms that widely explored for the wide range of biologically active compounds (Berdy, 2005). Actinobacteria comprise of G + C rich microorganisms (Embley and Stackebrandt, 1994), live in varying habitats and well established for the synthesis of bioactive secondary metabolites (Sengupta et al., 2015). Actinobacteria inhabiting marine environment (such as sea sediments, etc.) gain much attention (Lane and Moore, 2011) because they are considered more challenging to culture compared to their terrestrial relatives. They have special growth requirements and media composition. Furthermore, several Actinobacteria genera produce novel secondary metabolites with several bioactivities (Jensen et al., 2005). The recent grasp of the fact that marine environment can be a potential source for the novel isolates with novel natural products encourages intensive search and efforts from several groups. Nearly seventy five percent of all the known industrial antibiotics (Kieser et al., 2000) and numerous economically important compounds (Okami and Hotta, 1988) were obtained from the streptomyces’s. Actinobacteria have also ability to synthesize antiviral (Sacramento et al., 2004), antifungal (Zarandi et al., 2009), antitumor (Hong et al., 2009), insecticidal (Pimentel-Elardo et al., 2010), antioxidants (Janardhan et al., 2014), anti-inflammatory (Renner et al., 1999), anti-biofouling (Xu et al., 2010), immunosuppressive (Mann, 2001), anti-parasite (Pimentel-Elardo et al., 2010), plant growth promoting and herbicidal compounds (Sousa et al., 2008), enzyme inhibitors (Hong et al., 2009) and industrially important enzymes. Advance molecular tools such as metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metaproteomics can be employed directly for the extraction of DNA, RNA, and protein from environment samples (Mincer et al., 2005). Simultaneously, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified products were cloned and sequenced for identifying new Actinobacteria present in the environment samples (Monciardini et al., 2002; Riedlinger et al., 2004). Selective primer is now available to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from the specific Actinobacteria (Monciardini et al., 2002). Metabolic bioactive compounds obtained from marine or territorial Actinobacteria are commonly synthesized by enzymes polyketide synthases (PKS) or non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS). The PKS is categorized into three different groups such as types I, II, and III. Both NRPS peptides and PKS-type I are encoded by a number of modules which are multifunctional in nature (Ayuso-Sacido and Genilloud, 2005; Smith and Sherman, 2008). They form a series of biosynthesis reaction including acyl (PKS-I) or peptidyl (NRPS) chain initiation, elongation, and termination (Walsh, 2008). PKS-II molecules which are non-modular, complex of several single module proteins and their group of enzymatic activity act in an iterative manner to produce a polyketide (Gallo et al., 2013). The core PKS module comprises of a ketoacyl-synthase (KSα), a chain elongation factor (KSβ), and an acyl-carrier protein (Walsh, 2004; Das and Khosla, 2009). The PKS-III types are homodimer enzymes and act on the acyl-CoA without involving any acyl-carrier proteins (Shen, 2003). In continues searching potential bioactive, molecular methods will help for analyzing and comparing the genetic variations within these genes, in the normal laboratory condition strain’s specialized metabolites is not routinely produced which are useful for screening for molecule production is remains mostly a trial-and-error approach (Metsa-Ketela et al., 1999; Ayuso-Sacido and Genilloud, 2005; Gontang et al., 2010).

Extensive study has been done on various coastal areas of India for isolation and cultivation of Actinobacteria. However, the coast of Gujarat and especially, Gulf of Khambhat is relatively unexplored so far. Therefore, the present study was aimed to investigate the novel marine Actinobacteria using molecular methods and phylogenetic comparisons of the isolates. Furthermore, the isolated bacterial strain was functionally characterized by antibacterial and antioxidant activities. The present study provides a useful insight of bacteria inhabiting sea sediment of Arabian Sea. The isolated bacterial strain can be utilized further for the developing novel antibacterial compounds.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture Characterization of Marine Actinobacteria

The sea sediment samples (25 g) were collected from coastal areas of Gulf of Khambhat, Gujarat, India near a ship scraping industries (21°24′35.85″N, 72°11′54.1″E). Samples were transported to the laboratory under cool and control conditions, and immediately processed for the isolation of marine Actinobacteria (through serial dilution method) from sediment samples using modified Gause’s Synthetic Agar medium (Ye et al., 2009). In brief, 0.5 g sea sediment was suspended in 9.5 ml of sterile saline solution (0.9% NaCl). The suspended solution was serially diluted up to 10-10 in saline solution. About 100 μl diluted solution (10-3 to 10-10) was spread individually on modified Gause’s Synthetic Agar medium containing 0.01% (w/v) potassium dichromate to prevent the early growth of other bacteria and fungus. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 4–7 days, and Actinobacteria were preliminarily screened based on traditional morphology.

BIOLOG Assay of Selected Actinobacteria Isolates

The isolated bacteria were categorized by GEN III MicroPlate test assay performed with a Biolog system. The test panel comprises of 71 carbon sources with 23 chemical sensitivity assays and thus provides a “Phenotypic Fingerprint” of the tested microorganism. The Biolog system dissects and analyses the ability of a cell to metabolize all major substrates. Furthermore, other important physiological properties such as salt, pH, reducing power, chemical sensitivity and lactic acid tolerance were also determined. Overnight grown bacterial suspensions were mixed with 0.85% saline solution (5 mL) and IF-a was adjusted for 90–98% transmittance (T90) with a Biolog turbidimeter. Into each well of Biolog microplate, about 100 μL bacterial suspension was dispensed and incubated at 30°C. The developed color is compared with the Biolog species library to identify the bacterial isolates.

Average Well Color Development Assay

BIOLOG plates are commonly used for the analysis of microbial community function and micro-organism may be identified by the specific phenotype color fingerprint. The average well color development (AWCD) quantification of individual plate or individual well is performed by continuous monitoring of OD absorbance at 590 nm. The measured data was expressed as AWCD in response to incubation time (Garland and Mills, 1991).

Chemotaxonomic Identification

Chemotaxonomic identification of isolates was done by fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) analysis using gas chromatography coupled with Sherlock microbial identification system (MIS). The MIS gives the data output includes fatty acids composition and sample chromatographic run. The software computes “Sim index” which congregates values of samples FAME with the library and gives a Euclidian distance (ED).

Molecular Identification

Isolate RD-5 was grown in 50 mL of Gause’s Synthetic broth containing NaCl (4%, w/v) for 7 days. The mycelia were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and genomic DNA was extracted using phenol-chloroform extraction method (Hopwood et al., 1985). DNA quality and concentration were measured using a Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer.

The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using genomic DNA and universal bacterial primers (Table 1). The 50 μL PCR mixture was contained; 1–2 μL DNA template, 0.5 μL 20 μM of each primer, 5 μL of 10X buffer, 5 μL of dNTPs (2.5 mM), 0.5 μL Taq DNA (5 units/μL), and 41.5 mL ddH2O. PCR was done in MyCyclerT-100 (Bio-Rad, United States) using the optimized conditions (Yousuf et al., 2012, 2014a,b; Keshri et al., 2013; Keshri et al., 2015). The amplified products were analyzed on a 1.0% agarose gel, purified (QIAquick PCR Purification Kit, Qiagen, Germany) and sent to M/s Macrogen, S. Korea for the sequencing services. The 16S rRNA gene sequence was aligned using BioEdit software, compared with gene sequences available in the databases (NCBI + DDBJ + EMBL) and deposited in GenBank with an accession number KT588655. The putative phylogenetic affiliation was determined using the naïve Bayesian rRNA classifier and RDP-II database with the 95% confidence (Wang et al., 2007; Cole et al., 2009).

Table 1.

List of primers used for amplification of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and PKS-1gene fragments and 16S rRNA.

| Primer Name | DNA sequences (5′–3′) | Name of product | Target size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27F 1492R | 5′- AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG -3′ 5′- ACCTTGTTACGACTT -3′ | 16S rRNA | 1.5 Kb | Lane, 1991 |

| K1F M6R | 5′-TSAAGTCSAACATCGGBCA-3′ 5′-CGCAGGTTSCSGTACCAGTA-3′ | Type-I polyketide synthases (PKS-I) | 1.4 Kb | Ayuso-Sacido and Genilloud, 2005 |

| KSαF KSαR | 5′-TSGCSTGCTTGGAYGCSATC-3′ 5′-TGGAANCCGCCGAABCCTCT-3′ | Ketosynthase gene (PKS-II) | 700 bp | Metsa-Ketela et al., 1999 |

Bioactivity from Marine Actinobacteria

Primary Screening of Marine Actinobacteria for Antibacterial Activity

The isolated and purified Actinobacteria isolates were screened for antibacterial activity by cross streak method (Balagurunathan and Subramanian, 2001) using Mueller-Hinton agar (Himedia, India) against eight different pathogenic bacteria; Gram-negative (Escherichia coli NCIM 2065, Shigella boydii NCIM, Klebsiella pneumonia, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas sp. NCIM 2200, Salmonella enteritidis NCIM, and two Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus subtilis NCIM 2920 and Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 96). Plates containing well grown RD-5 strain was cross streaked with pathogenic bacteria at 90° angles and incubated at 37°C overnight. Antagonism was observed by noting the absence or presence of pathogenic bacterial growth.

Optimization of Growth Conditions for the Production of Bioactive Compounds

The promising strain RD 5 was cultured in six different media; starch casein agar, yeast malt extract agar (ISP2), glycerol asparagine agar (ISP5), inorganic salt agar (ISP-4), tyrosine agar (ISP-7) and gause’ synthetic agar (GSA) and incubated at 30°C for 7–9 days. The cell mass was measured by the dry weight of cell biomass after 24 h interval and compound production was measured using well diffusion method at 24 h interval for 9 days. The experiments were repeated three times for each assay.

Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivity Assay

The most promising isolate (RD-5) was grown in the optimized gause’s synthetic broth (GSB) media for the isolation of the active compounds. The selected isolate was inoculated in GSB medium and incubated for 7 days in shaking condition at 180 rpm at 30°C. Culture media was harvested every 24 h, centrifuged for 15 min at 8,000 rpm and collected supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of ethyl acetate followed by extraction with separating funnel (Ismail et al., 2009). The crude extract was obtained by removing the solvent using rotary evaporator. The dried crude extract was dissolved in methanol, and stock concentration was prepared as 100 mg/mL. The crude extracts (3 to 7 mg) were used for the bioactivity against different pathogenic bacteria using well diffusion method with Mueller Hinton agar (Nandhini and Selvam, 2011). Methanol used as a control and the bioactivity of extracts was noted based on the zone of inhibition. Furthermore, the bacterial extract was evaluated for the different antioxidant and radicals scavenging activity.

DPPH Radicals Scavenging Assay

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of the bacterial extract was determined using method reported by (Bersuder et al., 1998) using different concentrations of melanin (0.05–5.0 mg/mL). In test tubes, different concentration of melanin was taken, and volume was made up to 2 mL with distilled water. About 2 mL of 0.002% DPPH solution was added to each tube, mixed and incubated for 30 min in the dark. Reduction of DPPH radical was quantified at 517 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated as:

Where, Ac and As were the absorbance of the control and sample, respectively. The experiment was conducted in triplicates.

Hydrogen Peroxide Radical Scavenging Activity

A solution of hydrogen peroxide (40 mmol/L) was prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). To 4 mL of bacterial extract of different range of concentrations (0.05–5.0 mg/mL), 0.6 mL of H2O2 solution was added. The absorbance was measured at 230 nm by the UV-visible spectrometer and percentage inhibition of H2O2 scavenging activity was calculated (Keser et al., 2012; Mishra et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2016).

Where Ac and As were the absorbance of control and test samples, respectively. The experiment was conducted in triplicates.

Metal Chelating Activity

The ferrous ions chelating activity of the bacterial extract was analyzed (Dinis et al., 1994). Different concentration of extract (0.05–5.0 mg/mL) was made up with final volume 0.5 mL and mixed with 0.05 mL of 2 mM FeCl2. About 0.2 mL ferrozine solution (5 mM) was added to the reaction mix, shaken vigorously and kept for 10 min at room temperature. The absorbance of the reaction mix was estimated at 562 nm and percentage inhibition of ferrozine-Fe2+ complex formations was calculated:

Where Ac and As were the absorbance of control and test samples, respectively.

Cloning of PKS-I and PKS-II Genes

Two set of degenerative primers were designed to amplify internal fragment of KSα and PKS-I biosynthetic genes fragments from RD-5 strain (Table 1). PCR was done in 25 μl volume that contained 1X Taq buffer, 2.5 μL of dNTPs (2.5 mM), 20 pM primers (forward and reverse), 0.05 U of Taq DNA polymerase enzyme (Sigma, United States) and 10–15 ng genomic DNA. PCR was carried out with denaturation of the templete DNA at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 58°C for 120 s, for the KS of PKS-II domain while 55°C for 2 min was used for the amplification of K1F/M6R PKS-I gene and finally extension at 72°C for 4 min. Amplified PCR products were analyzed on 1% agarose gel, purified, cloned into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, United States) and transformed to E. coli DH5α. Recombinant plasmid DNA was extracted using alkaline lysis method and confirmed by PCR with vector-specific primers M13F and M13R. Both cloned genes fragments, PKS-1 and PKS-II were sequenced from M/s Macrogen Inc, South Korea and deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers MG459176 and MG459177, respectively.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The 16S rRNA gene sequences (KT588655) were subjected to BLASTn for the comparision with the other 16S rRNA gene sequences exist in GenBank and closest relative 16S ribosomal RNA sequences were retrieved from NCBI database (Zhang et al., 2000). Sequence alignment was performed with cluster W (Altschul et al., 1997), phylogenetic trees were constructed (using Mega ver. 6) with the neighbor-joining method and a bootstrap value of 1000 replicates (Tamura et al., 2013). The resultant sequence of both PKS-I and PKS-II genes fragment was also analyzed with BLASTx search and protein sequence were retrieve from NCBI, aligned and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining tree-making algorithm.

Statistical Analysis

Average well color development (AWCD), diversity richness (R), and Shannon evenness (E) were calculated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) of each strain based on color development with every 24 h. The cluster analysis was used to evaluate the most utilized substrate for each strain. The AWCD data was standardized to remove inoculum density effects. Ordination methods were used for principal component analysis (PCA) of the data taken at 96 h. The method categeorised samples on scatter plots of two or more axes and the most closest micro-organism come together (Randerson, 1993; Podani, 2000). For the comparision of numerical responses in the 95 substrates, PCA plot reduced the multivariate data set (variables or individuals) and exhibited any changes in the variation of the data.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of Actinobacterial Strains

A total of 11 different strains of Actinobacteria were isolated from Gulf of Khambhat, Alang, Bhavnagar, Gujarat. The distinctly different isolates based on their morphological and pigmentation were purified by repeated streak method on Gause’s Synthetic Agar medium and preserved at 4°C as on slant. All the isolates were screened with preliminary cross streak assay. Out of them, Isolate RD-5 was found novel, additionally exhibits potent activity against pathogenic bacteria.

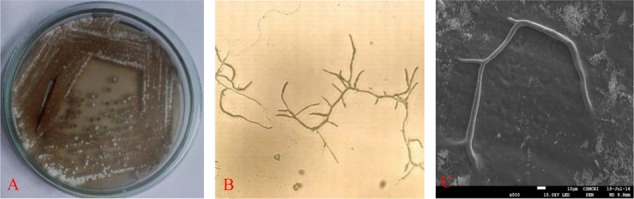

Selected strain was aerobic, Gram-positive and the colonies are dry, powdery, fuzzy with a concentric ring on agar surface which showed secondary metabolite production with diffusible brownish pigment were initially identified as Actinobacteria (Figure 1A). Microscopic examination of the strain was undertaken under a compound microscope. The short branched vegetative hyphae and aerial mycelia were sparse with a patchy distribution (Figures 1B,C).

FIGURE 1.

Isolated colonies on (A) gause’ synthetic agar (GSA) medium, (B) microscopy and (C) SEM image of RD-5.

Characterization of Microbial Strain(s) from the Selected Cultures Based on BIOLOG

All Actinobacteria were examined using Biolog System to obtain their metabolic profiles or biotyping. Biolog System analysis is based on carbon (C) utilization patterns of the Actinobacteria toward different carbon source. The ability to use a wide range of carbon source may indicate that the Actinobacteria were able to survive in the different environment in nature. Metabolic profiles resulted from Biolog GENE III System analysis indicated the 11 Actinobacteria were differentiated into different strains. As shown in (Supplementary Table S1) the eleven strains of Actinobacteria (RD-1 to RD-9 and RD 15 and RD 16) have the different capability to metabolize 95 carbon sources from GENE III microplates. The 95 carbon sources are categorized as polymers, sugar and sugar derivatives, carboxylic acids and methyl esters, carboxylic acids and methyl esters, alcohol, nucleosides and nucleotides and sugar phosphates. Of the 95 carbon sources, only 75 can be utilized by the all eleven strains of Actinobacteria. Strain RD-5 was one from the eleven colonies, showing significantly higher in carbon sources activity with 90 substrates followed by Strain RD-6 and RD-9 using 89 followed by RD-4, and RD-16 using 88 RD-15, RD-8 and RD-1, RD-2 and RD-7 and RD-3 with 87, 86, 82, and 81, respectively.

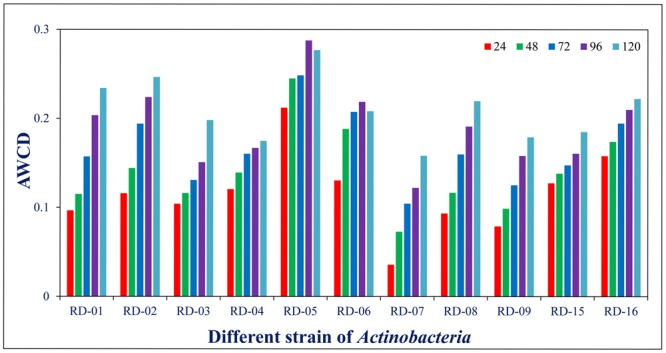

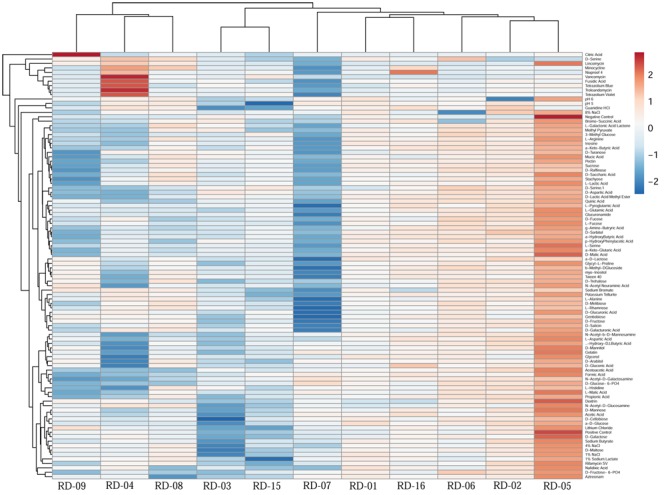

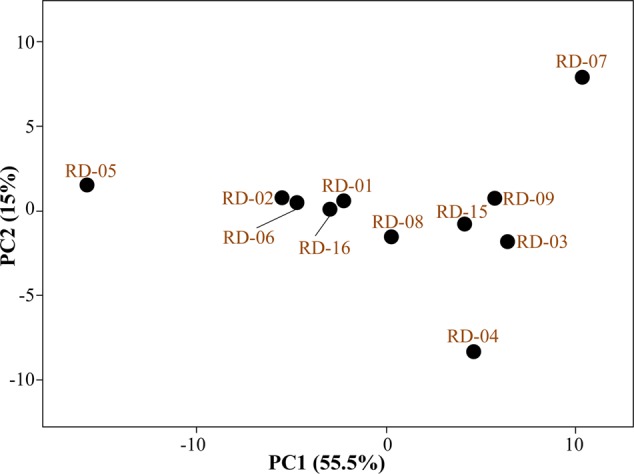

Monitoring Color Development in BIOLOGTM GENE III Plates with Other Reference Strain of Actinobacteria

Normalized value of AWCD further evidence that different strain cluster (Figure 2). In the hierarchical clustering with the complete linkage, RD-5 shows the most of the substrate is utilized in 96 h, but other strain is less used the substrate (Figure 3). PCA of ordinance methods scatter plot of each strain in BIOLOG allow the sample to be represented two or more axis PC1 (55.5%) second one PC2 (15%) RD-5 was scatter in PC2 axis (Figure 4).

FIGURE 2.

Average well color development (AWCD) of metabolized substrates in BIOLOG GENE III in every 24 h.

FIGURE 3.

This cluster heat map was generated using the http://biit.cs.ut.ee/clustvis/ online program package with Euclidean distance as the similarity measure and hierarchical clustering with complete linkage.

FIGURE 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of all 11 strain of Actinobacteria.

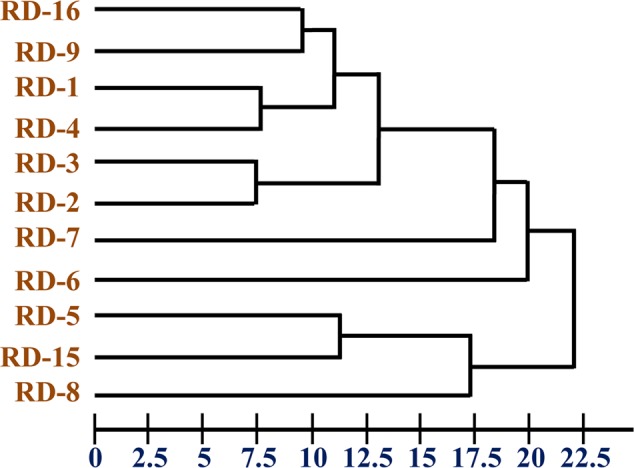

FAME Analysis

The chemotaxonomic study of the potential isolate RD-5 revealed that it belongs to the Actinobacteria. Saturated iso/anteiso- branched fatty acids with C15–C17 long chain was detected as major cellular fatty acids. The cluster analysis of FAME profile showed correlation among organisms by Euclidian distance. Cluster containing isolates identified was delineated at 22.5 ED (Figure 5) were closely matched those of Streptomyces, but considerable differences were recorded among the eleven strains.

FIGURE 5.

Dendrogram of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profiles novel strain RD-5 with reference strain.

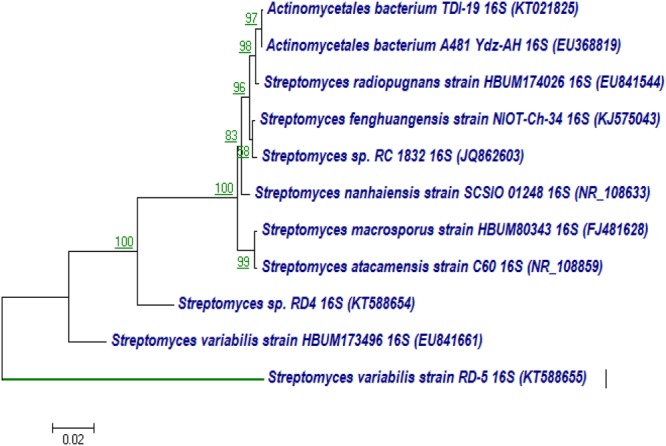

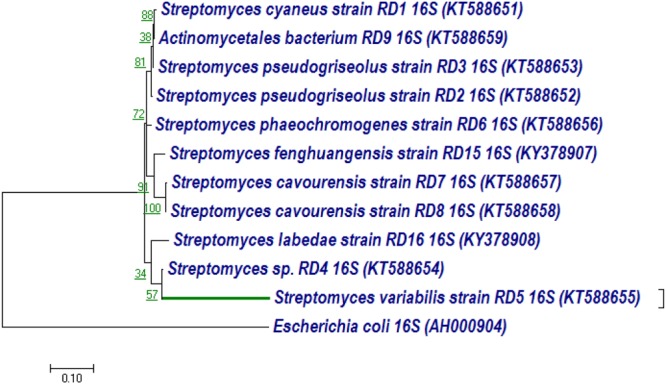

Phylogenetic Analysis of 16S rRNA

The 16S rRNA gene of RD-5 was amplified and sequenced (KT588655). The partial 16S rRNA gene sequence of RD-5 covered a stretch of 1382 bp having an average 54.8% G+C content. Nucleotides were subjected to BLASTn analysis (Table 2) which showed the 84% similarity with Streptomyces variabilis. The nucleotide sequences of the type strain were retrieved from the NCBI, and a phylogeny was studied (Figure 6). The phylogenetic position of the strain was within a cluster that contains Streptomyces fenghuangensis (KJ575043), Actinomycetales bacterium (KT021825), and Streptomyces sp. RD-4 (KT588654). Streptomyces sp. RD-5 was posed with as single branch and shared with 99% Query cover and 82% sequence identity with a closed group. Another phylogenetic tree was constructed with the reference strain, and out-group were taken E. coli, and it does not show any similarity match with reference strain (Figure 7).

Table 2.

The BLASTn results, of 16S rRNA according to the NCBI database.

| Description | Accession number | Maximum query cover | Maximum score | Total score | Maximum identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces variabilis strain RD-5 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KT588655.1 | 100% | 2553 | 2553 | 100% |

| Streptomyces variabilis strain HBUM173496 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | EU841661.1 | 99% | 1299 | 1299 | 84% |

| Streptomyces variabilis strain 173634 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | EU570414.1 | 99% | 1085 | 1085 | 81% |

| Streptomyces variabilis strain 173500 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | EU570413.1 | 99% | 1055 | 1055 | 81% |

| Streptomyces sp. RD4 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KT588654.1 | 99% | 1168 | 1168 | 82% |

| Streptomyces fenghuangensis strain NIOT-Ch-34 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KJ575043.1 | 99% | 1142 | 1142 | 82% |

| Streptomyces radiopugnans strain HBUM174024 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | EU841699.1 | 99% | 1127 | 1127 | 82% |

| Streptomyces nanhaiensis strain JA 24 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | KJ947850.1 | 94% | 1050 | 1050 | 81% |

| Streptomyces atacamensis strain C60 16S ribosomal RNA gene, partial sequence | NR_108859.1 | 99% | 1092 | 1092 | 81% |

FIGURE 6.

Neighbor-joining tree based on nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences showing relationships between strain RD-5 and closely related members of the genus Streptomyces. Numbers at nodes indicate levels of bootstrap support based on a neighbor-joining analysis of 1000 resampled datasets; only values above 50% are given. Bar, 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide position.

FIGURE 7.

Neighbor-joining tree based on nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences showing relationships between strain RD-5 and closely related members of the genus Streptomyces as reference strain with out-group Escherichia coli. Numbers at nodes indicate levels of bootstrap support based on a neighbor-joining analysis of 1000 resampled datasets; only values above 50% are given. Bar, 0.10 substitutions per nucleotide position.

These 16S rRNA sequences were also classified in Rdp Naive Bayesian rRNA Classifier Version 2.11 database with >1200 Nucleotide and Confidence threshold is 95% it shows domain Bacteria unclassified_Actinomycetales at the genus level.

Bioactivity from Marine Actinobacteria

Primary Screening of Antibacterial Activity

Isolated different marine Actinobacteria were primarily screened with the cross streak method for bioactivity against pathogenic bacteria. On the basis of maximum inhibition of pathogenic strain, RD-5 was selected for the further screening.

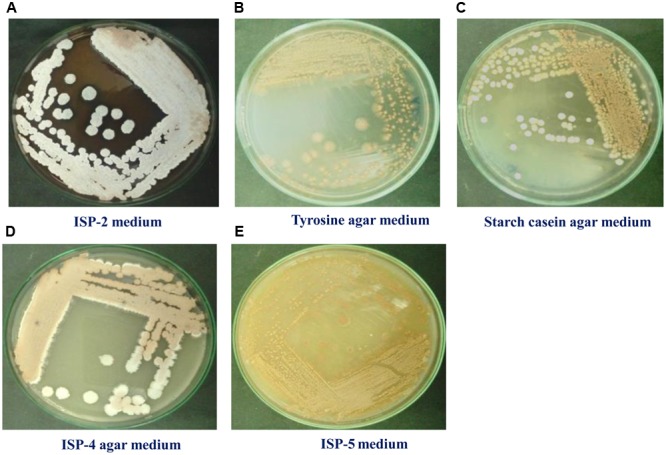

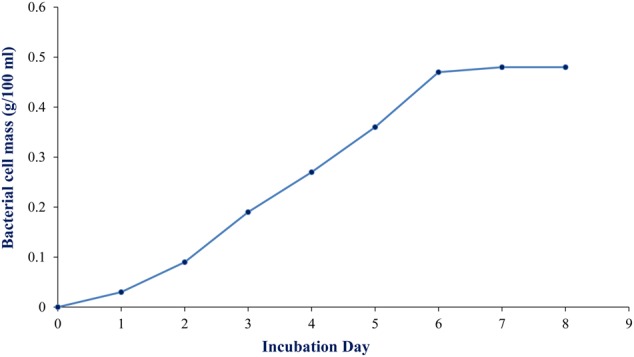

Culture Media Study and Optimization of Cell Growth and Production of the Compound

To maximize the antibacterial production as well as cell mass, strain RD-5 was cultured in five different media, out of six different media, GSA medium supposed to maximize the cell mass as (Table 3 and Figure 8) well as the production of antibacterial activity. The growth curve for strain RD-5 and the antibacterial activity produced in the GSA medium was measured every 24 h of the interval (Figure 9). Strain RD-5 showed the first phase of growth 72 h post inoculation. The second phase occurred during 168 h, and thereafter stationary phase occurred. This strain produced compounds after around 72 h and production increased depending on cell growth. The compounds produced were maximized at the end of the second phase. Shigella boydii and Klebsiella pneumonia showed maximum antibacterial activity from an extract of RD-5 which was 27 mm in both. While the response of Pseudomonas sp. was less compared to other pathogenic strains (19 mm).

Table 3.

Cultural characteristics of Streptomyces variabilis RD-5 on different media.

| Medium | Growth | Aerial mycelium | Substrate mycelium | Pigment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch casein agar | Moderate | Brownish white | Brownish white | None |

| Yeast malt extract agar (ISP2) | Good | White | Brownish white | Yellow |

| Inorganic salt agar (ISP-4) | Good | Brownish white | Brownish white | Yellow |

| Glycerol asparagine agar (ISP5) | Good | Slight orange | Light brown | Light yellow |

| Tyrosine agar (ISP-7) | Moderate | Light brown | Brownish white | None |

FIGURE 8.

Growth of RD-5 in different media such as (A) ISP-2 medium, (B) Tyrosine agar medium, (C) Starch casein agar medium, (D) ISP-4 agar medium and (E) ISP-5 medium.

FIGURE 9.

Growth curve of RD-5 at the indicated times, mycelial pellets were harvested for growth determination by biomass measurement.

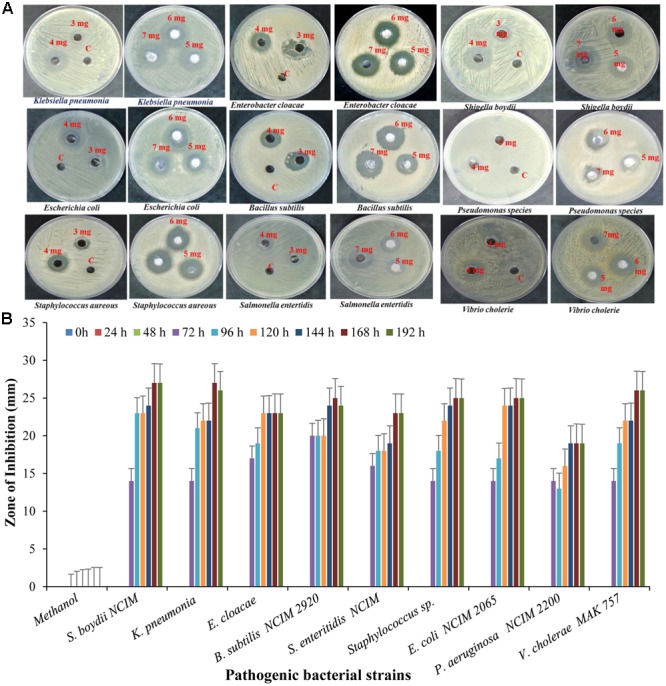

Secondary Screening of Antibacterial Compound

The bioactive compounds were extracted from the fermented broth using ethyl acetate solvent, and concentrated crude extract which was used as test compound was carried out by agar well diffusion method. The antibacterial activity of crude extract at concentration of 5 mg/well was assayed against pathogenic strain Shigella boydii (13 mm), Klebsiella pneumonia (24 mm), Enterobacter cloacae (16 mm), Bacillus pumilus (22 mm), Salmonella enteritidis (14 mm), Staphylococcus sp. (16 mm), E. coli (15 mm), Pseudomonas sp. (17 mm) (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Antibacterial activity of crude extract against different pathogenic strain with (A) different concentration and (B) different time interval.

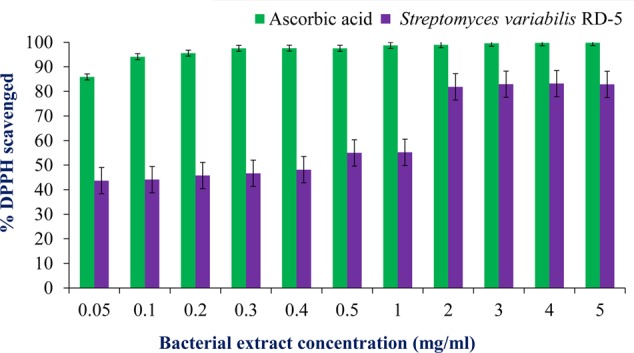

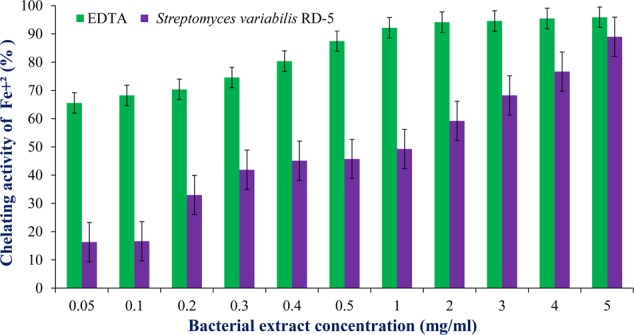

Antioxidant and Scavenging Activity

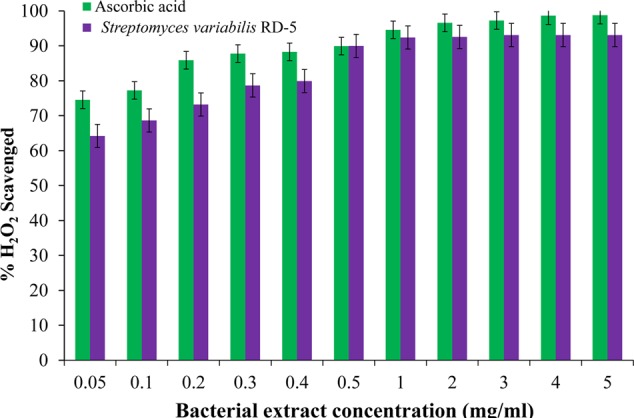

DPPH is a stable free radical having absorption maxima at 517 nm. The results of DPPH radical scavenging activity of ethyl acetate extract of S. variabilis is depicted in (Figure 11). Bacterial extract showed 43.67–82.86% DPPH free radical scavenging activity at 0.05–5.0 mg/mL as compared to ascorbic acid which showed 86% activity at 0.05 mg/mL concentration. The activity of the extract was increased with an increase in concentration and reached to around 55% at 1.0 mg/mL concentration against 98% of ascorbic acid. Further, increase in concentration marginally influenced activity. It was observed that extract of S. variabilis showed maximum activity at 2 mg/mL concentration after that slight difference was observed. The activity of the extract increased up to 2.0 mg/mL concentration, a further increase in concentration did not influence activity. Metal chelating activity of extracts of various Actinobacteria ranged from 16% as compared to Na-EDTA which showed 65% activity at 0.05 mg/mL concentration (Figure 12). With an increase in concentration of extract, the activity increased to 16–89% at 0.05–5 mg/mL while in case of Na-EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL, at concentration yielded 87.5% metal chelating activity. Here, S. variabilis exhibited maximum activity at 5 mg/mL concentration. H2O2 scavenging activity of extracts ranged from 64% as compared to ascorbic acid exhibiting 74.5% activity at 0.05 mg/mL concentration (Figure 13). As far as H2O2 scavenging activity is concerned, extract of S. variabilis exhibited activity almost at par with that of ascorbic acid.

FIGURE 11.

Antioxidant activity of bacterial extract with different concentration.

FIGURE 12.

Chelating activity of bacterial extract with different concentration.

FIGURE 13.

H2O2 scavenged activity of bacterial extract with different concentration.

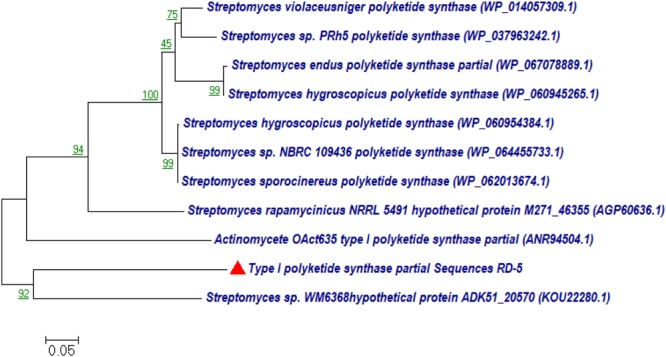

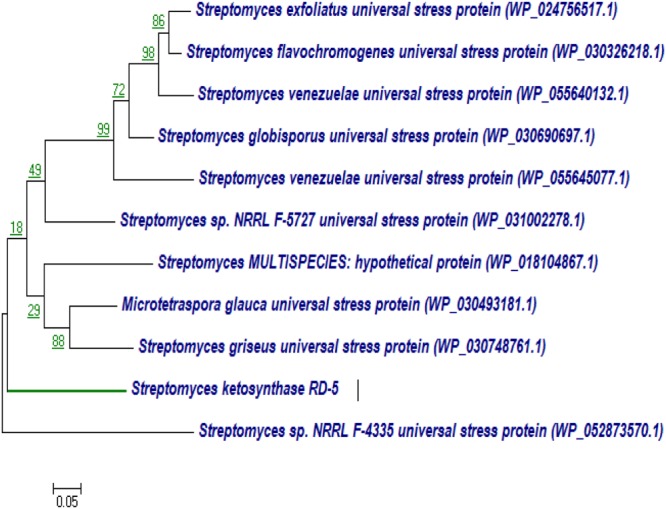

Phylogenetic Analysis PKS-I and PKS-II Genes

BLASTx analysis of PKS-I and PKS-II amino acid biosynthetic genes of strain RD-5 showed the 99–92% of query cover and 54–52% sequences identity with their closest matches (Tables 4, 5). The phylogenetic tree was inferred by maximum likelihood method using the amino acid sequences of both PKS-I and PKS-II of RD-5 novel strain. PKS-I gene sequences showed the maximum identity with S. hygroscopicus, Streptomyces sp. NBRC 109436, S. atratus, S. melanosporofaciens, and S. atratus with 59–56% identity (Figure 14). The PKS-II gene sequences showed the maximum identity of 71–49% with previously reported sequences. Amino acid search analysis showed similarity with universal stress and hypothetical proteins from Streptomyces sp. NRRL F-5727 (WP_031002278.1), S. globisporus (WP_030690697.1), S. exfoliates (WP_024756517.1), S. laurentii (BAU87338.1), and Streptomyces sp. CcalMP-8W (WP_018491225.1) (Figure 15).

Table 4.

The BLASTx results, of PKS-I according to the NCBI database.

| Description | Accession no. | Maximum query cover | Maximum score | Total score | Maximum identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyketide synthase (Streptomyces hygroscopicus) | WP_060954384.1 | 99% | 419 | 809 | 56% |

| Polyketide synthase (Streptomyces sp.) NBRC 109436 | WP_064455733.1 | 418 | 813 | 56% | |

| Polyketide synthase 12 (Streptomyces atratus) | SFY45126.1 | 99% | 414 | 709 | 59% |

| Type I polyketide synthase (Streptomyces caatingaensis) | WP_053161268.1 | 99% | 381 | 424 | 55% |

| type I polyketide synthase (Streptomyces auratus) AGR0001 | EJJ02441.1 | 99% | 381 | 514 | 54% |

| Type I polyketide synthase 3 (Streptomyces sp.) | APD71668.1 | 99% | 379 | 1103 | 53% |

| Beta-ketoacyl synthase (Streptomyces hygroscopicus) | WP_078638584.1 | 99% | 392 | 685 | 54% |

| Polyketide synthase 12 (Streptomyces melanosporofaciens) | SED16442.1 | 99% | 408 | 813 | 55% |

| Polyketide synthase (Streptomyces violaceusniger) | WP_014057309.1 | 99% | 408 | 817 | 56% |

| Polyketide synthase (Streptomyces hygroscopicus) | WP_078646099.1 | 99% | 407 | 808 | 55% |

Table 5.

The BLASTx results, of PKS-II according to the NCBI database.

| Description | Accession number | Maximum query cover | Maximum score | Total score | Maximum identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces sp.) WM6368 | WP_053703232.1 | 96% | 159 | 159 | 58% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces sp.) 3211 | WP_079403829.1 | 96% | 157 | 157 | 58% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces sp. H021) | WP_053631949.1 | 96% | 155 | 155 | 57% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces virginiae) | WP_030895366.1 | 96% | 155 | 155 | 57% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces globisporus) | WP_030690697.1 | 92% | 188 | 188 | 66 |

| Universal stress protein (Microtetraspora glauca) | WP_030493181.1 | 92% | 184 | 184 | 70% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces flavochromogenes) | WP_030326218.1 | 92% | 173 | 173 | 62% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces venezuelae) | WP_055640132.1 | 92% | 171 | 171 | 92% |

| Universal stress protein (Streptomyces griseus) | WP_030748761.1 | 92% | 169 | 169 | 68% |

| MULTISPECIES: universal stress protein (Streptomyces) | WP_030648525.1 | 92% | 168 | 168 | 63% |

FIGURE 14.

Representative neighbor-joining tree of PKS-I amino acid sequences. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions that occur per site.

FIGURE 15.

Representative neighbor-joining tree of PKS-II amino acid sequences. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions that occur per site.

Discussion

Adaptations of marine bacteria have developed prodigious metabolic and physiological ability to survive in the extreme conditions that allows them to produce different kind of metabolites, which could not be produced by the terrestrial ones. Actinobacteria are well established for producing secondary metabolites with novel antibiotics which are of immense importance to prevent multi-drug resistant pathogens. The Actinobacteria produce spores which generally resist desiccation and show to some extent higher resistance toward environmental fluctuation to adopt the harsh condition comparative to others microbes (Hopwood and Wright, 1973).

In the present study, total 11 different isolates were screened, out of them, one promising marine Actinobacteria strain, identified as S. variabilis RD-5 showed the novelty with antagonistic properties. The phylogenetic position of the S. variabilis RD-5 suggested that isolated strain from coastal areas of Gulf of Khambhat have a potential diverse arrangement with novelty which can be useful for many of the applications and can be explored broadly.

Culture medium, GCA, found to be the best for isolation of marine Actinobacteria S. variabilis RD-5. The strain showed optimum growth at 30°C on GSA and ISP-2 media. A retarded growth was also showen on Tyrosine agar medium and ISP-5 medium. S. variabilis RD-5 was characterized morphologically and microscopically which confirmed its identity as Streptomyces genus (Williams et al., 1989; Manfio et al., 1995).

BIOLOG analysis suggested higher AWCS in RD-5 compared to others reference strains of Actinobacteria. BIOLOG assay further showed that strain S. variabilis RD-5 utilized a wide range of substrates. The cluster and PC analyses showed substrate utilization pattern similar to other Actinobacteria community (Figures 5, 6). The cluster analysis and PCA showed the comparability of both experiments and further confirmed the overlap metabolic fingerprints among the different strains of Actinobacteria.

The16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis revealed that RD-5 is a novel strain, having identity below 85% as shown by RDP-II classifier. Phylogenetic analysis showed that RD-5 strain was closely related to novel Actinobacteria bacterium such as TDI19 (KT021825), S. radiopugnans strain HBUM174026 (EU841544), Streptomyces sp. RC 1832 (JQ862603), S. nanhaiensis strain SCSIO 01248 (NR_108633), isolated from different geographical location including deep-sea sediment (Tian et al., 2012).

PCR amplification and identification of these biosynthetic genes was very important for assessing its potential for both culturable and unculturable microorganism (Minowa et al., 2007). Large numbers of biologically active compounds are identifying which is encoded by a set of genes, in which PKS-I and PKS-II are responsible for the biosynthesis of the active metabolite (Ayuso-Sacido and Genilloud, 2005). The presence of types I and II PKS gene in S. variabilis RD-5 showed a direct correlation with the identified bioactive compound, which is polyketide in nature.

The extracted compound of S. variabilis RD-5 was found the most active against pathogenic bacteria, and thus it can play an important role in clinical appliances. Extracellular enzymes play a key role in the recycling of organic carbon and nitrogen compounds in biotechnology. The strain RD-5 exhibited highest antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumonia. The result showed that secondary metabolite active compounds containing antibacterial activities were extracellular and it could be extracted, quantified and further explored for the discovery of new drugs (Passari et al., 2015). To best of our knowledge, this is the first report of S. variabilis RD-5 having strong antimicrobial activity against bacteria. From the results, we concluded that the results of morphological, biochemical characteristics and polyphasic approach; the isolate S. variabilis RD-5 was the member of Actinobacteria, which secretes bioactivity with novel characteristics.

The crude extract was tested and found good antioxidant properties which can be useful for further research development to make it the industrially important. The radical scavenging activity of the extract was concentration dependent, and gradual increase of concentration increased the activity which was supported by the report of Kumaqai et al. (1993). The DPPH free radical scavenging assay was extensively used to measure antioxidant capacity. Antioxidants react with DPPH and reduce the DPPH molecules equal to the number of freely available hydroxyl groups (Matthäus, 2002). The DPPH scavenging activity depends on the degree of due to its ability to donate hydrogen proton. With the same concentration, the isolate was capable of reducing Fe3+ ions which indicated the presence of active compounds in the solvent extracts (Kekuda et al., 2010). S. variabilis RD-5 is potential sources of antioxidants, which reflects by high hydrogen peroxide activity, is useful in preventing the progress of various oxidative stress-related disorders (Poongodi et al., 2012). Hydrogen peroxide has ability to cross cell membrane easily and also reacts with metal ions (Fe2+ and/or Cu2+) to produce ROS (reactive oxygen species) such as hydroxyl free radical which have toxic effects (Swant et al., 2009). Thus, the present study suggests that the Actinobacterial extract of RD-5 can act as better antioxidant agents for removing H2O2.

According to a report of Thenmozhi and Kannabiran (2012), ethyl acetate extract of Streptomyces species VITSTK7, isolated from marine environment of the Bay of Bengal, exhibited 43.2% DPPH scavenging activity and 51% metal chelating activity at 10 mg/mL concentration. Similarly, Karthik et al. (2013) reported antioxidant activity of three marine Actinobacteria isolated from marine sediments of Nicobar Islands whereas phenolic compounds extracted from Streptomyces sp. LK-3 exhibited 76% DPPH scavenging activity at 100 μg/mL. Two phenolic compounds from Streptomyces sp. JBIR-94 and JBIR-125 showed DPPH scavenging activity with an IC value of 11.4 and 35.1 μM, respectively. Sowndhararajan and Kang (2013) studied free radical scavenging potential of culture filtrate of Streptomyces sp. AM-S1 isolated from forest humus soil in Gyeongsan, South Korea where ethyl acetate extract exhibited higher activity as compared to the lyophilised cell-free supernatant. According to Rao and Rao (2013), the extracts of Actinobacteria isolated from mangrove soil of Vishakhapatnam region showed 46–70% DPPH scavenging activity and 68–78% FRAP activity at 20 μg/mL concentration. Karthik et al. (2014) reported an extracellular protease produced by a marine Streptomyces sp. MAB 18 which exhibited antioxidant activity. Nocardiopsis alba isolated from mangrove soil collected from Andhra Pradesh, India, exhibited antioxidant activity. The potential fraction obtained by chromatography showed antioxidant activity at par with standard ascorbic acid (Janardhan et al., 2014). Nagaseshu et al. (2016) reported antioxidant activity of methanol extracts of Actinobacteria isolated from marine sediment collected from Kakinada coast. They also correlated the antioxidant activity of the extract which cytotoxic and antiproliferative activities.

The results of FAME of carbon chain length C15–C17 is consistent with the long carbon chain with saturated fatty acids which is used to produce phospholipids for Streptomyces cell membranes. Possibly S. variabilis RD-5 makes a triglyceride lyase which breaks bonds present between the carbon atoms, in resultant the FAMEs were generated (Lu et al., 2013). Further elucidation of genome sequences of strain RD-5 should be helpful for the investigation how the FAMEs were generated.

Conclusion

Adaptation of marine microorganism has developed prodigious physiological and metabolic capacities to survive in a harsh condition that triggered them to synthesize different metabolites, which could not be produced by the terrestrial ones. In the present study, S. variabilis RD-5 was isolated from Gulf of Khambhat, Alang, Bhavnagar, and screened for its ability to produce the bioactive compound. The extracted compounds show good antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Extracellular enzymes play a key role in recycling of organic carbon and nitrogen compounds in biotechnology.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KM and AM. Performed the experiments: RD and RK. Analyzed the data: RD, RK, and AM. Secured the funds to support this research: KM and BJ. Wrote the paper: RD and RK.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

CSIR-CSMCRI Communication No.: PRIS- 103/2017. This study was supported by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR; www.csir.res.in) and the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES; Sanction No. MoES/16/06/2013-RDEAS), Government of India, New Delhi. The authors are thankfully acknowledged Director, CSMCRI for his kind support and facility provided in this institute.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02420/full#supplementary-material

References

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso-Sacido A., Genilloud O. (2005). New PCR primers for the screening of NRPS and PKS-I systems in actinomycetes: detection and distribution of these biosynthetic gene sequences in major taxonomic groups. Microb. Ecol. 49 10–24. 10.1007/s00248-004-0249-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagurunathan R., Subramanian A. (2001). Antagonistic streptomycetes from marine sediments. Adv. Biosci. 20 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Berdy J. (2005). Bioactive microbial metabolites. J. Antibiot. 58 1–26. 10.1038/ja.2005.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersuder P., Hole M., Smith G. (1998). Antioxidants from a heated histidine-glucose model system. I: investigation of the antioxidant role of histidine and isolation of antioxidants by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 75 181–187. 10.1007/s11746-998-0030-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo U., Myera S., Brown L., Strobel G., Hess W. M., Hanks J. (2005). Scanning electron microscopy of some endophytic streptomycetes in snakevine-Kennedia nigricans. Scanning 27 305–311. 10.1002/sca.4950270606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. R., Wang Q., Cardenas E., Fish J., Chai B., Farris R. J., et al. (2009). The ribosomal database project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 141–145. 10.1093/nar/gkn879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Khosla C. (2009). In vivo and in vitro analysis of the hedamycin polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 16 1197–1207. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinis T. C. P., Madeira V. M. C., Almeida L. M. (1994). Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5- aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 315 161–169. 10.1006/abbi.1994.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. A., Rodriguez-Brito B., Wegley L., Haynes M., Breitbart M., Peterson D. M. (2006). Using pyrosequencing to shed light on deep mine microbial ecology. BMC Genomics 7:57. 10.1186/1471-2164-7-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley T. M., Stackebrandt E. (1994). The molecular phylogen and systematics of the actinomycetes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48 257–289. 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.001353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenical W., Jensen P. R. (2006). Developing a new resource for drug discovery: marine actinomycetes bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2 666–673. 10.1038/nchembio841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo A., Ferrara M., Perrone G. (2013). Phylogenetic study of polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases involved in the biosynthesis of mycotoxins. Toxins 5 717–742. 10.3390/toxins5040717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland J. L., Mills A. L. (1991). Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community-level sole-carbon-source utilization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57 2351–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontang E. A., Gaudencio S. P., Fenical W., Jensen P. R. (2010). Sequence-based analysis of secondary-metabolite biosynthesis in marine actinobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 2487–2499. 10.1128/AEM.02852-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow M., Williams S. T. (1983). Ecology of actinomycetes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37 189–216. 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.001201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong K., Gao A. H., Xie Q. Y., Gao H., Zhuang L., Lin H. P., et al. (2009). Actinomycetes for marine drug discovery isolated from mangrove soils and plants in China. Mar. Drugs 7 24–44. 10.3390/md7010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood D. A., Bibb M. J., Chater K. F., Kieser T., Bruton C. J., Kieser H. M., et al. (1985). Genetic Manipulation of Streptomyces: A Laboratory Manual. Norwich: John Innes Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood D. A., Wright H. M. A. (1973). Plasmid of Streptomyces coelicolor carrying a chromosomal locus and its inter-specific transfer. J. Gen. Microbiol. 79 331–342. 10.1099/00221287-79-2-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail S., Fouad M., Quotaiba A., Shahidi B. (2009). Comparative UV- spectra fermented cultural extract of antifungal active streptomyces isolates recovered from different ecology. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 3 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Janardhan A., Kumar A. P., Viswanath B., Saigopal D. V. R., Narasimha G. (2014). Production of bioactive compounds by Actinomycetes and their antioxidant properties. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2014:217030. 10.1155/2014/217030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. L., Bohonak A. J., Kelley S. T. (2005). Isolation by distance, web service. BMC Genet. 6:13. 10.1186/1471-2156-6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P. R., Mafnas C. (2006). Biogeography of the marine actinomycetes Salinispora. Environ. Microbiol. 8 1881–1888. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose P. A., Jha B. (2017). Intertidal marine sediment harbours actinobacteria with promising bioactive and biosynthetic potential. Sci. Rep. 7:10041. 10.1038/s41598-017-09672-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthik L., Kumar G., Keswani T., Bhattacharyya A., Chandar S. S., Rao K. B. (2014). Protease inhibitors from marine Actinobacteria as a potential source for antimalarial compound. PLOS ONE 9:e90972. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthik L., Kumar G., Rao K. V. B. (2013). Antioxidant activity of newly discovered lineage of marine actinobacteria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 6 325–332. 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60065-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekuda P. T. R., Shobha K. S., Onkarappa R. (2010). Studies on antioxidant and anthelmintic activity of two Streptomyces species isolated from Western Ghat soil of Agumbe, Karnataka. J. Pharm. Res. 3 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Keser S., Celik S., Turkoglu S., Yilmaz O., Turkoglu I. (2012). Hydrogen peroxide radical scavenging and total antioxidant activity of Hawthorn. Chem. J. 2 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Keshri J., Mishra A., Jha B. (2013). Microbial population index and community structure in saline–alkaline soil using gene targeted metagenomics. Microbiol. Res. 168 165–173. 10.1016/j.micres.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshri J., Yousuf B., Mishra A., Jha B. (2015). The abundance of functional genes, cbbL, nifH, amoA and apsA, and bacterial community structure of intertidal soil from Arabian Sea. Microbiol. Res. 175 57–66. 10.1016/j.micres.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieser T., Bibb M. J., Butner M. J., Charter K. F., Hopwood D. A. (2000). “Preparation and analysis of the genomic and plasmid DNA,” in Practical Streptomyces Genetics ed. Kieser T. (Norwich: The John Innes Foundation; ) 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaqai A., Fukui S., Tanaka M., Ikemoto K., Moriquchi S., Nabeshima S. (1993). PC-766B a new macrolide antibiotic produced by Nocardia brasiliensis II. Isolation, physico-chemical properties and structures elucidation. J. Antibiot. 46 1139–1144. 10.7164/antibiotics.46.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane A. L., Moore B. S. (2011). A sea of biosynthesis: marine natural products meet the molecular age. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28 411–428. 10.1039/c0np90032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. J. (1991). “16S/23S rRNA sequencing,” in Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics eds Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M. (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; ) 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Wang J., Deng Z., Wu H., Deng Q., Tan H., et al. (2013). Isolation and characterization of fatty acid methyl ester (FAME)-producing Streptomyces sp. S161 from sheep (Ovis aries) faeces. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 57 200–205. 10.1111/lam.12096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfio G. P., Zakrzewska-Czerwinska J., Atalan E., Goodfellow M. (1995). Towards minimal standards for the description of Streptomyces species. Biotechnologia 8 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mann J. (2001). Natural products as immune suppressive agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18 417–430. 10.1039/B001720P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus B. (2002). Antioxidant activity of extracts obtained from residues of different oilseeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 3444–3452. 10.1021/jf011440s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metsa-Ketela M., Salo V., Halo L., Hautala A., Hakala J., Mantsala P., et al. (1999). An efficient approach for screening minimal PKS genes from Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180 1–6. 10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00453-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincer T. J., Fenical W., Jensen P. R. (2005). Culture-dependent and culture-independent diversity within the obligate marine actinomycete genus Salinispora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 7019–7028. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7019-7028.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minowa Y., Araki M., Kanehisa M. (2007). Comprehensive analysis of distinctive polyketide and nonribosomal peptide structural motifs encoded in microbial genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 368 1500–1517. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A., Patel M. K., Jha B. (2015). Non-targeted metabolomics and scavenging activity of reactive oxygen species reveal the potential of Salicornia brachiata as a functional food. J. Funct. Foods 13 21–31. 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monciardini P., Sosio M., Cavaletti L., Chiocchini C., Donadio S. (2002). New PCR primers for the selective amplification of 16S rDNA from different groups of actinomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42 419–429. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn C. B. (2004). “Symbiotic associations,” in Marine Microbiology; Ecology and Applications ed. Watts A. (Trowbridge: Cromwell Press; ) 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaseshu P., Gayatridevi V., Kumar A. B., Kumari S., Mohan M. G., Malla R. (2016). Antioxidant and antiproliferative potentials of marine actinomycetes. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 8 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Nandhini S. U., Selvam M. M. (2011). Antibacterial Activity of The Streptomycetes Isolated from Marine Soil Sample. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 362–365. 10.1109/GTEC.2011.6167694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okami Y., Hotta K. (1988). “Search and discovery of new antibiotics,” in Actinomycetes in Biotechnology eds Goodfellow M., Williams S. T., Mordaski M. (London: Academic Press; ) 33–67. 10.1016/B978-0-12-289673-6.50007-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Passari A. K., Mishra V. K., Gupta V. K., Yadav M. K., Saikia R., Singh B. P. (2015). In vitro and in vivo plant growth promoting activities and DNA fingerprinting of antagonistic endophytic actinomycetes associates with medicinal plants. PLOS ONE 10:e0139468. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. K., Mishra A., Jha B. (2016). Non-targeted metabolite profiling and scavenging activity unveil the nutraceutical potential of psyllium (Plantago ovata Forsk). Front. Plant Sci. 7:431. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel-Elardo S. M., Kozytskam S., Bugni T. S., Ireland C. M., Moll H., Hentschel U. (2010). Antiparasitic compounds from Streptomyces sp. strains isolated from Mediterranean sponges. Mar. Drugs 8 373–380. 10.3390/md8020373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podani J. (2000). Introduction to the Exploration of Multivariate Biological Data. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Poongodi S., Karuppiah V., Sivakumar K., Kannan L. (2012). Marine actinobacteria of the coral reef environment of the Gulf of Mannar Biosphere Reserve, India: a search for antioxidant property. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 4 316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Qasim S. Z. (1999). The Indian Ocean: Images and Realities. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH; 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh S., Mathivanan N. (2009). Screening of marine actinomycetes isolated from the Bay of Bengal, India for antimicrobial activity and industrial enzymes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25 2103–2111. 10.1007/s11274-009-0113-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Randerson P. F. (1993). “Ordination,” in Biological Data Analysis: A Practical Approach ed. Fry J. C. (Oxford: Oxford University Press; ) 173–217. [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. V. R., Rao T. R. (2013). Molecular characterization and its antioxidant activity of a newly isolated Streptomyces coelicoflavus BC 01 from mangrove soil. J. Young Pharm. 5 121–126. 10.1016/j.jyp.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M. K., Shen Y. C., Cheng X. C., Jensen P. R., Frankmoelle W., Kauffman C. A., et al. (1999). Cyclomarins A-C, new anti-inflammatory cyclic peptides produced by a marine bacterium (Streptomyces sp.). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 11273–11276. 10.1021/ja992482o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riedlinger J., Reicke A., Zahner H., Krismer B., Bull A. T., Maldonado L. A., et al. (2004). Abyssomicins, inhibitors of para-aminobenzoic acid pathway produced by the marine Verrucosispora strain AB-18-032. J. Antibiot. 57 271–279. 10.7164/antibiotics.57.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacramento D. R., Coelho R. R. R., Wigg M. D., Linhares L. F. T. L., Santos M. G. M., Semedo L. T. A. S., et al. (2004). Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of an actinomycete (Streptomyces sp.) isolated from a Brazilian tropical forest soil. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20 225–229. 10.1023/B:WIBI.0000023824.20673.2f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Pramanik A., Ghosh A., Bhattacharyya M. (2015). Antimicrobial activities of actinomycetes isolated from unexplored regions of Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem. BMC Microbiol. 15:170. 10.1186/s12866-015-0495-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen B. (2003). Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7 285–295. 10.1016/S1367-5931(03)00020-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. L., Sherman D. H. (2008). An enzyme assembly line. Science 321 1304–1305. 10.1126/science.1163785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa C. S., Soares A. C. F., Garrido M. S. (2008). Characterization of streptomycetes with potential to promote plant growth and biocontrol. Sci. Agric. 65 50–55. 10.1590/S0103-90162008000100007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowndhararajan K., Kang S. C. (2013). Evaluation of in vitro free radical scavenging potential of Streptomyces sp. AM-S1 culture filtrate. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 20 227–233. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Dai S., Jiang S., Wang G., Liu G., Wu H., et al. (2010). Culture-dependent and culture independent diversity of Actinobacteria associated with the marine sponge Hymeniacidon perleve from the South China Sea. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 98 65–75. 10.1007/s10482-010-9430-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swant O., Kadam V. J., Ghosh R. (2009). In vitro free radical scavenging and antioxidant activity of Adiantum lunulatum. J. Herb. Med. Taxicol. 3 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thenmozhi M., Kannabiran K. (2012). Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of marine actinomycetes Streptomyces sp VITSTK7. Oxid. Antioxid. Med. Sci. 1 51–57. 10.5455/oams.270412.or.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X. P., Long L. J., Wang F. Z., Xu Y., Li J., Zhang J., et al. (2012). Streptomyces nanhaiensis sp. nov., a marine streptomycete isolated from a deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 62 864–868. 10.1099/ijs.0.031591-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. T. (2004). Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: modularity and versatility. Science 303 1805–1810. 10.1126/science.1094318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. T. (2008). The chemical versatility of natural-product assembly lines. Acc. Chem. Res. 41 4–10. 10.1021/ar7000414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Auler A. S., Edwards R. L., Cheng H., Ito E., Wang Y., et al. (2007). Millennial-scale precipitation changes in southern Brazil over the past 90000 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34 1–5. 10.1029/2007GL031149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. T., Goodfellow M., Alderson G. (1989). “Genus Streptomyces Waksman and Henrici 1943, 339AL,” in Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology Vol. 4 eds Williams S. T., Sharpe M. E., Holt J. G. (Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; ) 2453–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J., Luo Y., Xie S., Xu J. (2011). Serinicoccus profundi sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from deep-sea sediment and emended description of the genus Serinicoccus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61 16–19. 10.1099/ijs.0.019976-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., He H., Schulz S., Liu X., Fusetani N., Xiong H., et al. (2010). Potent antifouling compounds produced by marine Streptomyces. Bioresour. Technol. 101 1331–1336. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L., Zhou Q., Liu C., Luo X., Na G., Xi T. (2009). Identification and fermentation optimization of a marine-derived Streptomyces griseorubens with anti-tumor activity. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 38 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf B., Keshri J., Mishra A., Jha B. (2012). Application of targeted metagenomics to explore abundance and diversity of CO2-fixing bacterial community using cbbL gene from the rhizosphere of Arachis hypogaea. Gene 506 18–24. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf B., Kumar R., Mishra A., Jha B. (2014a). Unravelling the carbon and sulphur metabolism in coastal soil ecosystems using comparative cultivation-independent genome-level characterisation of microbial communities. PLOS ONE 9:e107025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf B., Kumar R., Mishra A., Jha B. (2014b). Differential distribution and abundance of diazotrophic bacterial communities across different soil niches using a gene-targeted clone library approach. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 360 117–125. 10.1111/1574-6968.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarandi M. E., Bonjar G. H. S., Dehkaei F. P., Moosavi S. A. A., Farokhi P. R., Aghighi S. (2009). Biological control of rice blast (Magnaporthe oryzae) by use of Streptomyces sindeneusis isolate 263 in greenhouse. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 6 194–199. 10.3844/ajassp.2009.194.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. S., Gavin M., Dahiya A., Postigo A. A., Ma D., Luo R., et al. (2000). Exit from G1 and S phase of the cell cycle is regulated by repressor complexes containing HDAC-Rb-hSWI/SNF and Rb-hSWI/SNF. Cell 101 79–89. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80625-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.