Abstract

Objective:

To compare the short term anti-schizophrenic efficacy and side effect profile of aripiprazole with risperidone.

Methodology:

The study was a non-randomized, naturalistic, rater blinded, prospective, 8-12 weeks, comparative trial between the risperidone and aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia. Patients already getting treatment with aripiprazole (10 to 30 mg/day) or risperidone (3 to 8mg/day) were recruited. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), Simpson Angus Scale (SAS), Udvalg for Klinske Undersogelser (UKU) Scale, Clinical Global Impression-severity scales were administered by principal investigator on the day of recruitment. Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI, waist, hip, waist circumference) blood pressure and pulse rate were measured on day 1 and during follow up. All tests except MINI plus were administered again after 8-12weeks.

Results:

Both aripiprazole and risperidone treated patients have shown significant improvement on positive and negative symptoms but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Mean improvement in patient rated improvement scale score showed a trend towards significance favoring aripiprazole. Common adverse events (seen in ≥ 5% of patients) as assessed by the UKU Scale occurred more frequently in the risperidone group than in the aripiprazole group. Drug induced extra pyramidal symptoms were more common in risperidone treated patients. Aripiprazole showed less treatment emerged weight gain.

Conclusion:

Aripiprazole is equally efficacious and better tolerated than risperidone in patients with schizophrenia over a short-term period of eight weeks. Aripiprazole showed better patient satisfaction and side effect profile.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, aripiprazole, risperidone, anti-psychotics, dopamine stabilizer

1. INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a chronic disabling disease that often results in drastically impaired quality of life and can deprive patients of active, satisfying participation in social activities and work. It can have far-reaching effects on personality, cognition and global functioning and is characterized by positive symptoms (such as delusions and hallucinations), negative symptoms (such as lack of motivation, poverty of speech and social withdrawal) and cognitive symptoms.

Treatment with antipsychotic drugs is the cornerstone of schizophrenia treatment [1]. A dose dependent effect of antipsychotic treatment in the level of disability in schizophrenia patients is explained. Treatment with antipsychotic is associated with less disability, whereas being off treatment is associated with three times more disability [2].

Atypical antipsychotics have replaced conventional antipsychotics as first line drugs in the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia [3]. Despite the ability of dopamine antagonists to reduce psychosis and delay symptom exacerbations, the long-term outcome of schizophrenia has remained poor. During the 1950–1960s, two major changes occurred in the way schizophrenia was treated. The first was a shift in treatment focus from long-term custodial to community based care. The second change was the introduction of efficacious pharmacotherapy. However, there is doubtful evidence that these two major revolutions altered the outcome of schizophrenia during the twentieth century. Changing methodologies during this period make before and after antipsychotic drug therapy comparisons difficult, but schizophrenia remains a chronic illness with substantial functional impairments for most cases [4].

The majority of currently approved pharmacological agents for the treatment of schizophrenia target psychotic symptoms as their primary effects [5]. Currently, guidelines for the management of schizophrenia advocate long-term treatment with antipsychotic drugs. These exert their therapeutic effect primarily through antagonism of dopamine receptors [6]. Older drugs, such as haloperidol and the phenothiazines, are generally effective but produce extra pyramidal symptoms in up to 75% of patients and have little influence on primary negative symptoms. Additionally, approximately 40% of patients show only a partial response to treatment [7]. The newer atypical antipsychotics, for example risperidone and olanzapine, antagonize serotonin 5-HT2A as well as dopamine D2 receptors, and their lower propensity to produce extra pyramidal symptoms places them as first line alternatives to older drugs. With some of the atypical agents, however, other unwanted effects such as weight gain and QT prolongation can be problematic [5][8].

The search for agents with improved tolerability profiles has produced a new class of drugs termed ‘dopamine-serotonin system stabilizers’, which have a novel pharmacological profile [9]. In dopamine-rich environments, aripiprazole is likely to have antagonist effects on dopaminergic transmission, whereas relative agonist activity is more prominent in dopamine-depleted environments [7]. This dopamine stabilization effect may be of particular therapeutic value in schizophrenia as it offers the potential to alleviate side effects caused by the blockade of dopamine receptors. This new drug profile focuses on aripiprazole, the first of these atypical antipsychotics. Aripiprazole has been investigated in many clinical trials for the treatment of acute relapsing and stable chronic schizophrenia [10].

1.1. Efficacy of Aripiprazole in Schizophrenia

Aripiprazole showed statistically significant improvement in positive and negative symptoms (PANSS SCORE) of schizophrenia in multicentre, double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial in adolescents [11]. Significant benefits are observed in open label trial in the treatment of first episode schizophrenia [12]. In a systematic review of RCTs (N=4125 patients) aripiprazole was compared with placebo, haloperidol, perphenazine, olanzapine and risperidone. More patient allocated to aripiprazole completed studies with fewer relapses compared to placebo [13].

Partial responders to clozapine there is a slight difference in the PANSS and CGI scores after the aripiprazole addition [14].

Intramuscular aripiprazole is equally efficacious to intramuscular haloperidol [15]. In a long term (52 weeks) efficacy and safety study, aripiprazole was found to be far better than haloperidol in terms of lower discontinuation rate, improvement in negative symptom, depressive symptoms but similar improvements on positive symptoms [16].

Neurocognition and its influencing factors in the treatment of schizophrenia is studied comparing aripiprazole with other atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone) results showed that all the molecules compared are efficacious but quetiapine seemed to achieve the most favorable cognitive improvement [17].

In a nutshell, Cochrane review of clinical randomized trials comparing aripiprazole with placebo, typical and atypical antipsychotics drugs for schizophrenia, concluded that Aripiprazole is significantly better than placebo in efficacy; compared with other antipsychotics; there were no significant benefits for aripiprazole with regard to global state, mental status and quality of life but aripiprazole had a significantly better side effect profile. Aripiprazole may be effective for the treatment of schizophrenia, but it does not differ greatly from typical and atypical antipsychotics with respect to treatment response and efficacy [19]. In comparison with atypical antipsychotics, aripiprazole has less risk for increasing serum prolactin, weight gain and prolongation of QTc interval [19].

1.2. Role of Risperidone in Schizophrenia

Many studies compared efficacy and side effect profile of risperidone with typical antipsychotics. Risperidone showed better performance in terms of efficacy on PANSS Score, with a favorable result on adverse events on abnormal movements. Majority of the studies were comparisons with haloperidol; very few studies compared risperidone with other first generation antipsychotics which is a draw back because haloperidol has more propensity of having drug induced movement disorders [20]. When Risperidone was compared with amisulpride no significant difference was found between the two compounds [21]. Olanzapine seemed more acceptable than risperidone when numbers of patients leaving the study early due to any reason were compared. There was a non-significant trend for an increased acceptability of olanzapine in the longer term when all patient discontinuations were considered. Those taking olanzapine reported fewer extra pyramidal side effects in the medium term, reported fewer new episodes of Parkinsonism and received less antiparkinsonian medication. There was a non-significant trend for risperidone to cause less weight gain than olanzapine in both the medium term and longer term [21].

In summary, review suggests that there is little to choose between risperidone and other atypical antipsychotics when the short and medium term outcomes measured in the available studies are compared [21]. In head to head comparison studies of antipsychotics, 42 reports identified by the authors, 33 were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. In 90.0% of the studies, the reported overall outcome was in favor of the sponsor‘s drug. This pattern resulted in contradictory conclusions across studies when the findings of studies of the same drugs but with different sponsors were compared. Potential sources of bias occurred in the areas of doses and dose escalation, study entry criteria and study populations, statistics and methods, and reporting of results and wording of findings [22].

1.3. Need for Current Study

The review of articles regarding efficacy and side effect profile of two atypical antipsychotics, aripiprazole and risperidone showed that second generation antipsychotics are a heterogeneous group of drugs with varied efficacy and side effect profile. There were very few head to head comparison trials between atypical antipsychotics. Many RCTs comparing aripiprazole with risperidone gave conflicting results, and may have been subjected to bias as most of the studies were sponsored by manufacturers of aripiprazole. Finally, there are very few head to head comparison studies of aripiprazole with risperidone in Indian populations.

1.4. Aims and Objectives

To compare the short term anti-schizophrenic efficacy and side effect profile of aripiprazole with risperidone.

1.5. Hypothesis

Short term anti-schizophrenic efficacy of aripiprazole is lower compared to that of risperidone.

1.6. Methodology

The study was a non-randomized, naturalistic, rater blinded, prospective, 8 weeks, comparative trial between risperidone and aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia. Approval was gained from the institutional review board and ethics committee. Either patient or their caregiver gave informed, written consent.

Patients satisfying Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision criteria for schizophrenia and already getting treatment with aripiprazole (10 to 30 mg/day) or risperidone (3 to 8mg/day) from outpatient and inpatient facilities of the department of psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore; a tertiary level teaching institute were recruited in the study.

Recruitment of patients was continued till we got not less than 15 patients each in risperidone and aripiprazole group. Sample size calculation was not done. Patients above 16 completed years of age are selected for study. Patients who were on oral antipsychotics within eight days and were on depot antipsychotics within two months prior to recruitment are excluded from study. Patients getting any psychotropic drugs (except trihexyphenidyl or benzodiazepines) other than risperidone or aripiprazole are not included. For assessment following instruments were used. 1. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus. The M.I.N.I. was designed as a brief structured interview for the major Axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10.Has acceptably high validation and reliability scores. This is used here to confirm the diagnosis and detect any co-morbid conditions. 2. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) which is designed to assess the occurrence of dyskinesias in patients receiving neuroleptic treatment. AIMS is easy to use in routine clinical settings which measures the abnormal movements under four headings orofacial movements, extremity movements, trunk movements and global judgment. 3. Simpson Angus Extrapyramidal Rating Scale (SAS) is designed for assessing parkinsonian and related extrapyramidal side effects. 4. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a strictly operationalized, comprehensive and standardized scale for the assessment of psychiatric symptomatology in schizophrenia. The instrument is shown to have good reliability and criterion validity. PANSS has been used extensively in various researches, particularly drug trials. Primary investigator was trained in administering the scale using teaching videos. We did inter-rater reliability; Pearson correlation was 0.9 (p=0.002). 5. Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement and Clinical Global Impressions-Severity [23] scales are used to assess the severity of symptoms in psychiatric patients. On repetition, it can evaluate response to treatment. Udvalg for Klinske Undersogelser (UKU) Scale [24] is developed to provide a comprehensive side effect rating scale with well-defined and operationalized items to assess the side effects of psycho pharmacological medications. UKU is designed for use in both clinical trials and routine clinical practice. Rating is independent of whether the symptom is regarded as being drug-induced.

1.7. Procedure

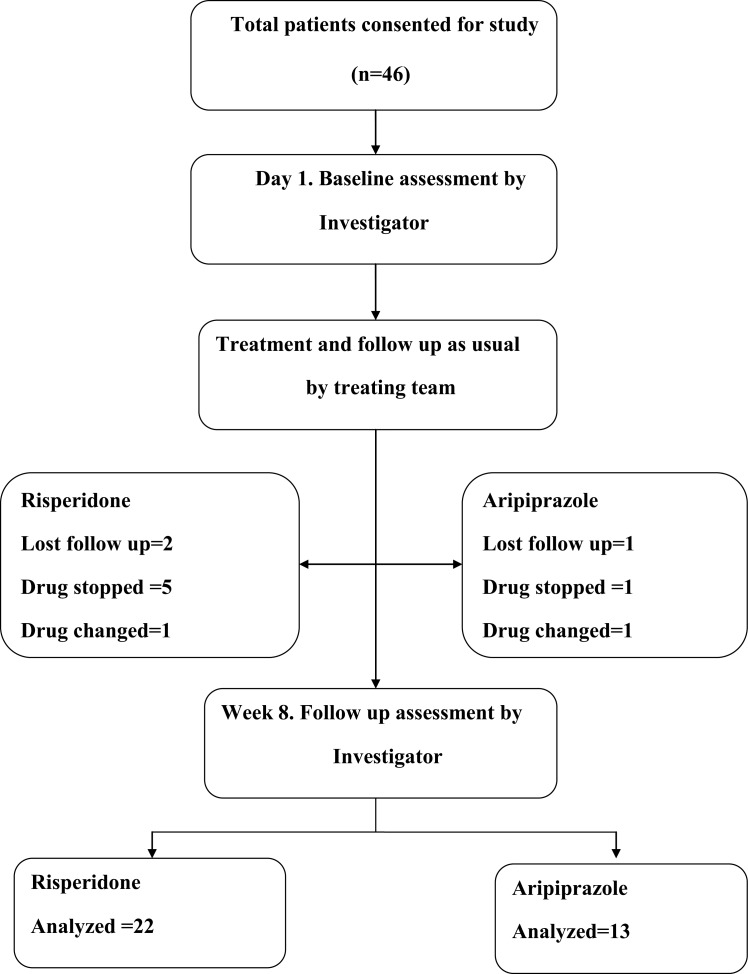

Patients fulfilling the above inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited. Patients were recruited after obtaining written informed consent from the patient and / or family member. The choice and dosage of drugs were decided by the treating team throughout the study period and were not interfered with for the purpose of the study. Diagnosis was confirmed by MINI plus. Socio-demographic details were recorded. Patients who developed symptoms requiring additional modality of treatment (e.g. ECT for suicidal ideas or catatonia, antidepressants for associated depressive symptoms) during the study period were noted and analyzed as outcome measures. Patients with co-morbid substance dependence syndromes (except nicotine) were excluded. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), [25] Simpson Angus Scale (SAS), [26] Clinical Global Impression-severity [27][28] scales were administered by the principal investigator on the day of recruitment. Anthropometric measurements (height, weight, BMI, waist, hip, waist circumference) blood pressure and pulse rate were measured on day 1 and during follow up. All tests except MINI plus were administered again after 8+/-2weeks. Also both clinician and patient rated global improvement. The principal investigator was trained to administer scales using teaching videos. The principal investigator was blinded to the drugs received by the patients. The frequency and dosages of trihexyphenidyl and benzodiazepines were noted. For patients with varying doses of risperidone or aripiprazole during the study period, average daily doses were calculated. The flow chart in Fig. (5) shows the details of participants through each stage of this study.

Fig. (5).

Flow diagram of participants through each stage of a randomized trial of this study.

1.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 13.0 software for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic and clinical data of the sample. Chi-square test for discrete variables and independent sample t-test for continuous variables were used to compare baseline socio-demographic and clinical profiles. Scores on PANSS, AIMS, and SAS Scales across assessment points were analyzed using two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA). Side effects on UKU Scale [29] were compared using Mann-Whitney U Test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

1.9. Results

The flow chart shows the details of participants through each stage of the study (Fig. 5). Total 46 patients consented for study (risperidone =30, aripiprazole=16). Eleven patients dropped out from the study (risperidone group =8, aripiprazole group =3) Table 2 shows the comparison between those who completed study and those lost for follow up. Older patients were over represented in the group that was lost for follow-up. More patients coming from rural areas completed the study. Otherwise, these groups were comparable. At the time of recruitment, all patients were off-medications for at least eight days or drug naïve. In both groups, patients were followed up to an average of 56 days. There was no difference between the groups in total days of follow up.

Table 2.

Comparisons of completers Vs those who were lost for follow up.

| Variables | Completed follow-up (n=35) | Lost follow-up (n=11) | t/X2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risperidone# | 22(73.3) | 8(26.7) | 0.359 | 0.549 |

| Aripiprazole# | 13(81.2) | 3(18.8) | ||

| Baseline* PANSS | 71.55(28.64) | 74.37(22.49) | 37.756 | 0.481 |

| Female# | 14(40) | 2(18.2) | 1.756 | 0.185 |

| Age* | 29.09(7.56) | 34.91(7.48) | -2.23 | 0.031 |

| Illness duration in months* | 41.57(38.05) | 65.45(59.42) | -1.576 | 0.122 |

| Rural domicile# | 25(71.4) | 4(36.4) | 4.417 | 0.036 |

| Drug naïve# | 19(54.3) | 6(54.5) | 0.000 | 0.988 |

*All values in cells are mean (SD) #All values in cells are mean (%).

1.10. Socio-Demographic and Clinical Profile at Baseline

Table 1 shows socio-demographic and clinical variables of the patients in the two groups. Both groups were comparable with respect to sociodemographic profile including age, gender, place of origin, education, occupation, duration of illness, family history of psychiatric disorder/hypertension/ diabetes mellitus. Both group had comparable severity in terms of total PANSS, negative, positive, general psycho- pathology subscale scores of PANSS and CGI-S. Significantly more patents in risperidone group were drug naïve (66.7% vs.31.2%; p=0.022).

1.11. Efficacy Parameters

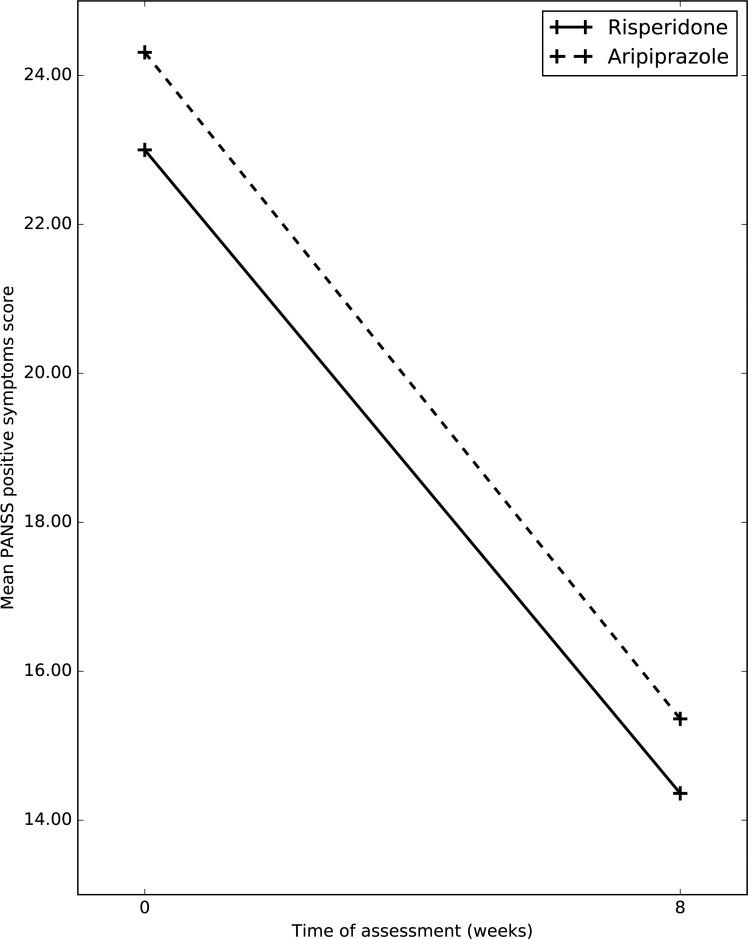

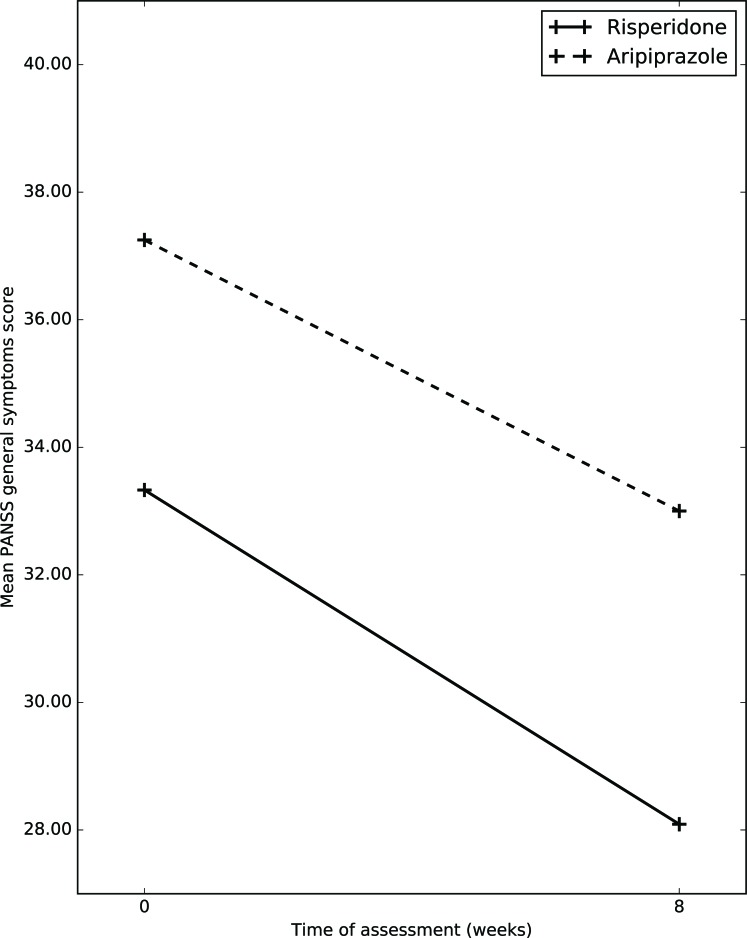

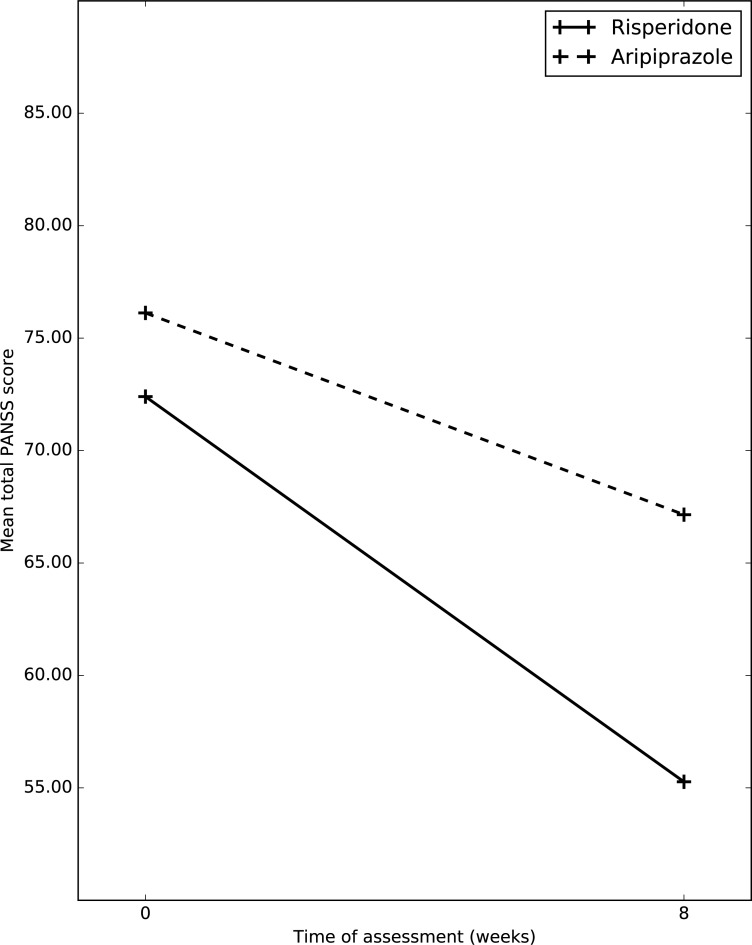

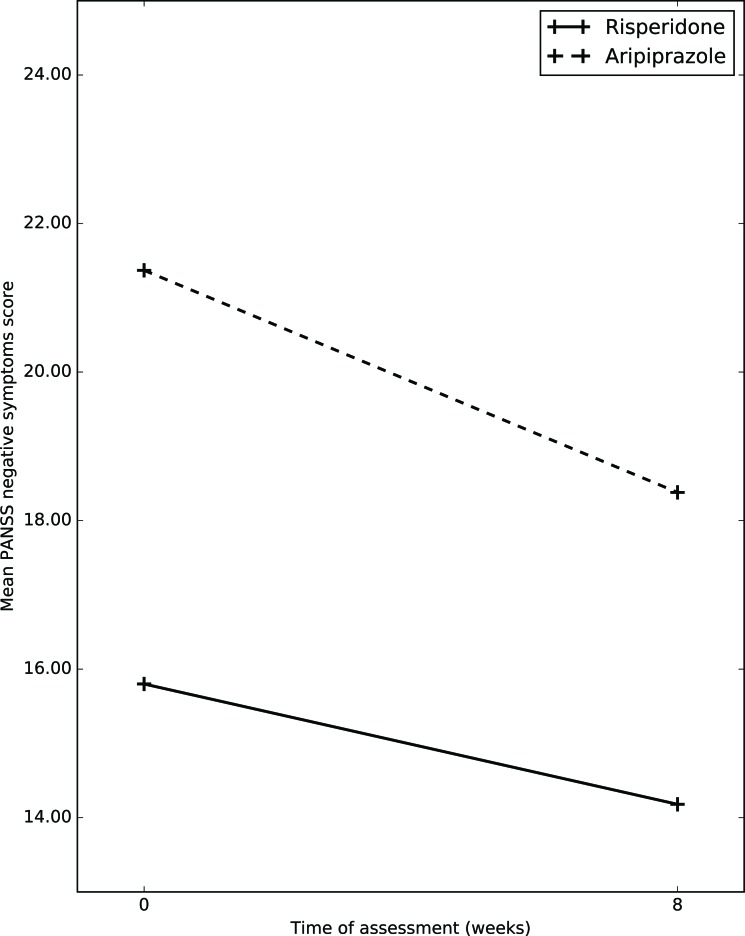

1.11.1. Efficacy on PANSS Scale (Table 3, Figs. 1-4)

Table 3.

Efficacy parameters.

| Scale | Assessment | Risperidone (n=22) | Aripiprazole (n=13) | F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive symptoms | Baseline | 23.00(6.53) | 24.31(6.92) | 54.04* | 0.853 | 0.313 |

| Follow up | 14.36(6.54) | 15.36(6.18) | ||||

| Negative symptoms | Baseline | 15.80(7.65) | 21.37(8.98) | 7.41* | 4.548* | 1.029 |

| Follow up | 14.18(6.44) | 18.38(7.07) | ||||

| General symptoms | Baseline | 33.33(7.27) | 37.25(10.55) | 6.51* | 3.196 | 0.116 |

| Follow up | 28.09(12.23) | 33.00(10.55) | ||||

| Total PANSS | Baseline | 72.40(17.44) | 76.12(33.16) | 22.23* | 3.390# | 0.000 |

| Follow up | 55.27(17.63) | 67.15(20.67) | ||||

| CGI-S | Baseline | 4.67(1.00) | 3.47(1.27) | 43.03* | 0.503 | 0.016 |

| Follow up | 4.50(1.31) | 3.23(1.23) |

*p<0.05, # p<0.1; F1=Occasion Effect; F2=Group Effect; F3=Group x Occasion Effect.

Fig. (1).

Changes in mean PANSS positive symptoms score between the two groups.

Fig. (4).

Changes in mean PANSS general symptoms score between the two groups.

1.11.1.1. Positive Symptoms

Mean total positive symptoms subscale score on PANSS in risperidone group at baseline was 23(6.53); whereas at week 8, it was 14.36(6.54). Mean total positive symptoms subscale score on PANSS in aripiprazole group at baseline was 24.31(6.92); whereas at week 8, it was 15.36(6.18) After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both group over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in PANSS positive scores, (p=0.000); whereas between groups no significant difference was noticed (p=0.579).

1.11.1.2. Negative Symptoms

Mean total negative symptoms subscale score on PANSS in risperidone group at baseline was 15.8(7.65); whereas at week 8, it was 14.18(6.44) Mean total negative symptoms subscale score on PANSS in aripiprazole group at baseline was 21.37(8.98); whereas at week 8, it was 18.38(7.07). After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both group over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in PANSS negative subscale scores, (p=0.010); whereas between groups no significant difference was noticed (p=0.318).

1.11.1.3. General Psychopathology

Mean total general psychopathology subscale score on PANSS in risperidone group at baseline was 33.33(7.27); whereas at week 8, it was 28.09(12.23) Mean total general psychopathology symptom subscale score on PANSS in aripiprazole group at baseline was 37.25(10.55) whereas at week 8, it was 33(10.55) After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both group over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in PANSS general psycho- pathology subscale scores, (p=0.016); whereas between groups no significant difference was noticed (p=0.736).

1.11.1.4. Total PANSS Score

All values in cells are mean (SD).

Mean total PANSS score in risperidone group at baseline was 72.40(17.44); whereas at week 8, it was 55.27(17.63) Mean total PANSS score in aripiprazole group at baseline was 76.12(33.16); whereas at week 8, it was 67.15(20.67) After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both group over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in total PANSS score, (p=0.000); whereas between groups no significant difference was noticed, (p=0.999) ANCOVA was conducted to assess the group difference using baseline total PANSS scores as co-variate and final total PANSS scores as outcome variable. The result was not significant (p=0.3).

1.11.2. Efficacy on CGI Scale

1.11.2.1. Clinical Global Impression- Severity Scale (Table 4)

Table 4.

Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events reported by ≥5% of patients assessed using UKU Scale.

| Adverse Events |

Risperidone

(n=21) n (%) |

Aripiprazole

(n=13) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Asthenia * | 11(45.9) | 0 |

| Sedation | 7(29.2) | 1(7.7) |

| Falling memory | 2(8.3) | 0 |

| Increased duration of sleep | 6(25) | 1(7.7) |

| Reduced duration of sleep | 2(8.4) | 1(7.7) |

| Rigidity | 2(8.4) | 0 |

| Hypokinesia* | 9(37.5) | 0 |

| Hyperkinesias | 0 | 1(7.7) |

| Tremor | 4(16.7) | 0 |

| Akathisia | 1(4.2) | 1(7.7) |

| Accommodation disturbance | 2(8.4) | 0 |

| Increased salivation | 2(8.4) | 0 |

| Constipation | 1(4.2) | 1(7.7) |

| Orthostatic dizziness* | 4(16.7) | 0 |

| Rash | 2(8.4) | 0 |

| Diminished sexual desire* | 4(16.7) | 0 |

| Head ache | 4(16.7) | 1(7.7) |

*p≤0.05.

Mean Clinical Global Impression – Severity score in risperidone group at baseline was 4.76(1.00); whereas at week 8, it was 4.50(1.31) Mean CGI-S score in aripiprazole group at baseline was 3.47(1.27); whereas at week 8, it was 3.23(1.23) After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both group over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in total PANSS score, (p=0.000); whereas between groups no significant difference was noticed, (p=0.937).

1.11.2.2. Clinician Global Improvement Scale

Mean improvement in clinician rated improvement scale score in risperidone was 4.95(3.45) and that of aripiprazole group was 5.61(2.81). When compared these values using independent sample t-test; there was no clinically significant difference between the group (p= 0.540).

1.11.2.3. Patient Global Improvement Scale

Mean improvement in patient rated improvement scale score in risperidonewas 5.00(4.05) and that of aripiprazole group was 7.07(2.98). When compared these values using independent sample t-test; there showed a trend towards significance favoring aripiprazole, (p=0.089).

1.12. Adverse Events

1.12.1. UKU Scale

The most common adverse events (seen in ≥ 5% of patients) as assessed by the UKU Scale are shown in Table 4. Asthenia, (45.9% vs. 0%; p=0.003) hypokinesia, (37.5% vs. 0%; p=0.008) orthostatic dizziness, (16.7% vs. 0%; p=0.082) diminished sexual desire (16.7% vs. 0%; p=0.02) occurred more frequently in the risperidone group than in the aripiprazole group. Two patients who were started on risperidone stopped medication because of severe skin rash. Other treatment-emergent adverse events occurred at comparable frequencies in both treatment groups.

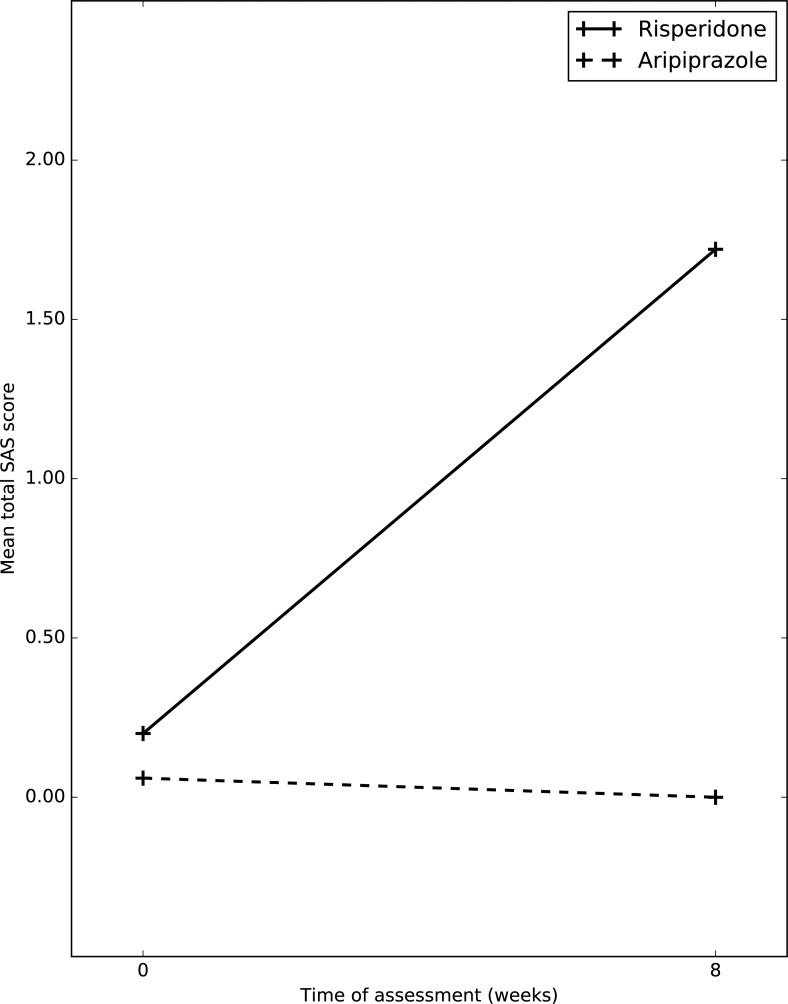

1.12.2. Simpson Angus Scale

Table 5, Fig. 6 shows changes in the mean total SAS scores. Aripiprazole was clearly superior compared to risperidone. After application of RMANOVA, it was shown that, in both groups over a period of 8 weeks there was significant improvement in total SAS score, (p=0.024); comparing between groups there was significant difference noticed, (p=0.014).

1.12.3. Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale

Both risperidone and aripiprazole group did not show significant change in mean total AIMS score during eight week follow up period (p=0.130).

1.12.4. Anthropometry (Weight, BMI, waist, waist circum- ference, hip circumference)

Table 6 shows mean change in weight, BMI, waist, waist circumference, hip measurements. A mean change was observed in BMI, (20.78 to 22.33 vs. 20.73 to 21.06, p=0.05) waist, (75.01 to 76.38 vs. 75.28 to 74.38). Results clearly favor the aripiprazole group (p=0.02).

1.12.5. Need for Antiparkinsonian Medication

Table 7 shows use of Trihexyphenidyl in both groups. 100% of risperidone group received antiparkinsonian medication vs. 18% in aripiprazole group (p=0.000).

1.13. Discussion

This study is a rater blinded naturalistic 6-8 weeks prospective study comparing the short term efficacy and side effect profile of aripiprazole with risperidone in patients with schizophrenia. 46 patients participated in the study: 30 in risperidone group and 16 in aripiprazole group. The most important finding of this study was that aripiprazole had similar short-term efficacy compared to risperidone. Moreover, aripiprazole emerged as a better drug in terms of side effect profile as assessed by UKU, AIMS, SAS scales and anthropometric measurements. The efficacy was evident across a range of parameters including total PANSS scores, sub-scores on PANSS, CGI-S and CGI-I. Patient rated global improvement scale showed a trend towards significance (p=0.08) favoring aripiprazole. Additionally, even after controlling for baseline PANSS scores, there was no group difference with respect to improvement in total PANSS scores.

Our results are consistent with some studies [19][30] but differ from few other studies [31]. The efficacy of aripiprazole has been evaluated in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in short and long- term trials [12][13][16][32]. Aripiprazole was effective in treating both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in short-term studies [12][32c][32d]. Our study finding is similar to the finding in a short term RCT [30] which showed aripiprazole is equally efficacious compared to risperidone.

Aripiprazole demonstrated superiority with respect to the following important adverse events (AEs): asthenia, hypokinesia, orthostatic dizziness which is consistent with findings from most studies [30][32d]. Both self-reported and objective measures for extra-pyramidal symptoms (EPS) showed that aripiprazole did better than risperidone, (p=0.014). In fact, EPS and abnormal movements remained unchanged or improved slightly with aripiprazole, while they worsened with risperidone. This is consistent with findings from numerous controlled trials which have reported that the rate of aripiprazole-induced extra pyramidal side effects was reported similar to placebo and needed less antiparkinsonian medication [16][33]. Considering that antipsychotic-induced movement disorders are among the most common AEs encountered during antipsychotic treatment and that they are commonly implicated in poor treatment compliance [4], this finding has important implications for long-term treatment and outcome in patients with schizophrenia.

In our study, all patients in risperidone received anti- parkinsonian medication. This finding needs to be interpreted by keeping in mind that most of patients in the risperidone group were started on Trihexyphenidyl prophylactically. This is a routine practice among psychiatrists in our centre based on the following considerations: risperidone is associated with significant EPS at relatively higher doses and that majority of the patients are treated on out-patient basis. Moreover, patients are called for follow-up after a gap of 6-8 weeks once the treatment is started. Even with this action, patients on risperidone needed further increase in THP dosage during their next follow up visit. In contrast only few patients on aripiprazole needed antiparkinsonian medications (p=0.00). Additionally, even with higher dosage of THP; risperidone group showed higher scores on SAS (p=0.014). Weight gain (p=0.06), waist measurement (p=0.02) and BMI (p=0.05) With respect to these, aripiprazole did remarkably well. Weight gain is a common side-effect of antipsychotics, particularly atypical agents [4]. In our study mean change was favorable to the aripiprazole group. Increases in body weight can have serious implications for general health (including increased risk of metabolic syndrome, cardio- vascular disorders and mortality) and are associated with decreased treatment adherence [34]. Our results are consistent with numerous earlier studies that have reported minimal increases in bodyweight in recipients of aripiprazole 15–30 mg/day recipients both in short [30][32g] as well as in long-term [16] clinical trials. Sexual side effects: Even here, aripiprazole did remarkably well (p=0.02). This finding is an extremely important one that could have ramifications in domains such as treatment adherence and quality of life. In a community based study [35] on sexual dysfunction and prolactin level comparing aripiprazole and standard of care (SOC = olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone); aripiprazole had potential to reduce sexual side effects. The ability of aripiprazole to reduce prolactin level [35] may have resulted in this particular finding. In contrast, risperidone is associated with considerable hyperprolactinemia [34]. Two patients in the risperidone group discontinued treatment due to skin rash. The two drugs did not differ with respect to the following adverse effects: headache, sedation, insomnia, akathesia and constipation demonstrated that aripiprazole was superior to risperidone. Differences in the mechanism of action of these two drugs and their neurobiological correlates may partly explain the differences in efficacy as well as side effect profiles. Risperidone is a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist. Blockade of dopamine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway is thought to mediate antipsychotic efficacy, in particular the ability to decrease positive symptoms [36]. However, D2 receptor blockade in the mesocortical, nigrostriatal, and tuberoinfundibular pathways is correlated with a increased liability for extra pyramidal symptoms (EPS) and hyperprolactinemia unwanted side effects of antipsychotic therapy [36b].

Aripiprazole has a partial agonist action at the D2 receptor. Partial agonist action has unique functional and clinical consequences; it reduces D2 hyperactivity in mesolimbic dopamine neurons to a degree that is sufficient to exert an antipsychotic action on positive symptoms, even though they do not completely shut down the D2 receptor. At the same time, it reduces dopamine activity in the nigrostriatal system to a degree that is insufficient to produce EPS [36b]. David Mamo, et al. [37] reported that at clinically effective doses (10–30 mg/day) aripiprazole exerts more than 80% striatal dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia. Correspondingly, higher striatal D2 occupancy (>90%) was associated with the development of extra pyramidal side effects (dystonia, parkinsonism). Aripiprazole was distinguished by a low serotonin 5-HT2:D2 affinity ratio [52% (SD=18) versus 87% (SD=4), respectively] and a low 5-HT1A receptor occupancy (mean=16%). Authors have implied that aripiprazole’s partial D2 agonist properties accounted for a low propensity for extra pyramidal side effects.

1.14. Methodological Considerations

This was a rater blinded study. Rater bias can be avoided by this study design. Such an occurrence would have important implications for the interpretation of trials in psychiatry, since even in double-blind studies, blindness can often not be fully maintained, as different drugs tend to have different side-effect profiles subjecting the findings of the trials to observer biases. With respect to our study, we hypothesized that aripiprazole may be less efficacious when compared to risperidone. Hence there was no scope for observer bias. This was a naturalistic study because the investigator followed up patients who were already started on risperidone or aripiprazole by the respective treating team. Moreover, all clinical decisions were taken by the respective treating teams e.g. which antipsychotic to be started, dosage, need for other medication etc. We did not recruit patients exclusively for the purpose of the study. In this sense, we believe that our results can be generalized more closely to real life clinical practice. Although this was not a randomized control design, all base line sociodemographic and clinical profile were comparable across groups. (Even though aripiprazole patients had more PANSS scores on baseline, they were not statistically significant) Patients were not blinded to drugs that they were getting. This is unlikely to bias the results as patients in our setting rarely read details of the medications that they take. At the time of recruitment, all patients were off-treatment at least for a period of 8 days (30.55%) some were never treated (69.44%). Hence our patients were drug naïve with respect to their current episodes. Dosages of the study drugs were not fixed and those who received concomitant medications were not excluded from study. Both groups received adequate therapeutic [19, 38] doses (mean dose-risperidone=5.53, aripiprazole =18.43) which were decided by the treating team based on clinical situations. This gave the opportunity to know that how many patients on each group needed increase or decrease in dosage as well as the need for concomitant medications. Drug compliance was assessed from the history given by the patients’ family members. Although sophisticated instruments were not used, this information is very reliable and valid as they form an inseparable part of the patient-care. Standardized instruments were used. (PANSS, CGI, SAS, AIMS, UKU). These scales helped for a comprehensive and objective assessment of psychopathology as well as side effect profile. Most of the studies discussed earlier did not use standardized scales to measure AEs. The principal investigator was trained to administer PANSS Scale using teaching videos. The inter-rater reliability (five videos) for the rater was found to be good (Pearson correlation=0.986; p=0.002) Sample size was small. This may have contributed to the type-II error. But, looking at the mean values of the results, whatever differences that may have emerged by taking larger sample sizes would not have made clinical meaning.

Limitations

This study was not a double blind randomized control trial. Sample size calculation was not done. Sample size was small. This may have contributed to the type-II error. Patients selected from a clinic contribute to selection bias and may be difficult to generalize to larger general population. Study was done in tertiary center at a South Indian state which caters more of people at that locality and nearby states.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it appears that aripiprazole is equally efficacious and better tolerated than risperidone in patients with schizophrenia over a short-term period of eight weeks. Aripiprazole also had better patient satisfaction.

Implication of this Study

In the background of recent controversies/inconsistencies in the psychopharmacologic literature, aripiprazole may be considered as a first line antipsychotic agent.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Rights

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Fig. (2).

Changes in mean PANSS negative symptoms score between the two groups.

Fig. (3).

Changes in mean total PANSS score between the two groups.

Fig. (6).

Changes in mean total SAS score between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed study.

| Variables | Risperidone (n=22) | Aripiprazole (n=13) | t/X2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years* | 29.41(8.62) | 28.54(5.59) | 0.325 | 0.747 |

| Female# | 9(40.9) | 5(38.5) | 0.020 | 0.885 |

| Rural# | 16(72.7) | 9(69.2) | 0.049 | 0.825 |

| Education in years* | 9.45(4.91) | 9.54(5.71) | 0.046 | 0.995 |

| Unemployed# | 12(54.5) | 7(53.8) | 0.216 | 0.995 |

| Illness Duration in months* | 38(33.72) | 47.62(45.28) | -0.717 | 0.478 |

| Family history Psychiatric disorders HTN DM |

10(45.5) 5(22.7) 5(22.7) |

3(23.1) 3(23.1) 5(38.5) |

1.75 0.991 0.001 |

0.186 0.319 0.981 |

| Total PANSS* | 72.42(17.44) | 76.12(33.16) | -0.502 | 0.619 |

| CGI-S* | 4.67(1.00) | 3.47(1.27) | 0.768 | 0.447 |

| Drug naïve # | 20(66.7) | 5(31.2) | 5.275 | 0.022 |

*All values in cells are mean (SD) #All values in cells are mean (%).

Table 5.

Changes in mean total SAS score between the two groups.

| Scale | Assessment | Risperidone n=21 | Aripiprazole n=13 | F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAS Total score |

Baseline | 0.20 (0.92) | 0.06 (0.25) | 5.618* | 6.471* | 6.758* |

| Follow up | 1.72 (2.36) | 0.00 |

*p<0.05; F1=Occasion Effect; F2=Group Effect; F3=Group x Occasion Effect.

Table 6.

Comparison of mean change in anthropometric measurements.

| Measurements | Assessments | Risperidone (n=21) | Aripiprazole (n=13) | F1 | F2 | F3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | Baseline | 55.06(11.88) | 56.15(13.05) | 27.691* | 0.065 | 3.726 |

| Follow up | 57.47(12.28) | 55.50(11.96) | ||||

| BMI | Baseline | 20.78(4.30) | 20.73(4.23) | 26.538* | 0.308 | 3.954* |

| Follow up | 22.33(4.77) | 21.06(3.84) | ||||

| Waist | Baseline | 75.01(10.86) | 75.28(9.50) | 5.901* | 0.130 | 5.269* |

| Follow up | 76.38(11.46) | 74.38(78.60) | ||||

| Waist circumference | Baseline | 83.18(22.22) | 81.28(13.09) | 15.416* | 0.540 | 3.257 |

| Follow up | 87.50(25.43) | 81.15(12.95) | ||||

| Hip | Baseline | 92.65(20.73) | 91.37(11.11) | 5.3* | 0.339 | 0.120 |

| Follow up | 95.28(24.14) | 91.00(11.51) |

*p<0.05; F1=Occasion Effect; F2=Group Effect; F3=Group x Occasion Effect.

Table 7.

Requirement of antiparkinsonian medication.

| THP Used | Risperidone (n=30) | Aripiprazole (n=16) | ×2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | 0 (100%) | 13 (81.2%) | 34.192 | 0.000 |

| 2mg | 25 (83.3%) | 3 (18.8%) | ||

| 4mg | 3 (10%) | 0 | ||

| 6mg | 2 (6.7%) | 0 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

Footnotes

Study was done part of academic training during the primary investigator’s post graduate course. No external funding received. No conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Citrome L., Volavka J. Atypical antipsychotics: revolutionary or incremental advance? 2002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Thirthalli J., Venkatesh B.K., Naveen M.N., Venkatasubramanian G., Arunachala U., Kishore K.K., Gangadhar B.N. Do antipsychotics limit disability in schizophrenia? A naturalistic comparative study in the community. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2010;52(1):37–41. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58893. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.58893]. [PMID: 20174516]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Excellence N.I. Guidance on the use of newer (atypical) antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia . 2002.

- 4.Casey D.E. Barriers to progress--the impact of tolerability problems. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(Suppl. 1):S15–S19. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200101001-00004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200101001-00004]. [PMID: 11252523]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell M., Young P.I., Bateman D.N., Smith J.M., Thomas S.H. The use of atypical antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999;47(1):13–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00849.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00849.x]. [PMID: 10073734]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehman A.F., Lieberman J.A., Dixon L.B., McGlashan T.H., Miller A.L., Perkins D.O., Kreyenbuhl J. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161((2)(Suppl.)):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burris K.D., Molski T.F., Xu C., Ryan E., Tottori K., Kikuchi T., Yocca F.D., Molinoff P.B. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302(1):381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1124/jpet.102.033175]. [PMID: 12065741]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1997;154(4) Suppl.:1–63. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.1. [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1176/ajp.154.4.1]. [PMID: 9090368]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter W.T., Koenig J.I. The evolution of drug development in schizophrenia: past issues and future opportunities. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2061–2079. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGavin J.K., Goa K.L. Aripiprazole. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(11):779–786. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216110-00008. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200216110-00008]. [PMID: 12383035]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Findling R.L., Robb A., Nyilas M., Forbes R.A., Jin N., Ivanova S., Marcus R., McQuade R.D., Iwamoto T., Carson W.H. A multiple-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral aripiprazole for treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1432–1441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07061035. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07061035]. [PMID: 18765484]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.Y., Ham B.J., Kang R.H., Paik J.W., Hahn S.W., Lee M.S., Lee M.S. Trial of aripiprazole in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2010;64(1):38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02039.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.02039.x]. [PMID: 20416024]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Sayeh H.G., Morganti C., Adams C.E. Aripiprazole for schizophrenia. Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;189(2):102–108. doi: 10.1192/bjp.189.2.102. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.189.2.102]. [PMID: 16880478]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanachev A., Ansermot N., Crettol Wavre S., Nowotka U., Stamatopoulou M. E., Conus P., Eap C. B. Addition of aripiprazole to the clozapine may be useful in reducing anxiety in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. . Case Reports in Psychiatry, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Andrezina R., Marcus R.N., Oren D.A., Manos G., Stock E., Carson W.H., McQuade R.D. Intramuscular aripiprazole or haloperidol and transition to oral therapy in patients with agitation associated with schizophrenia: sub-analysis of a double-blind study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006;22(11):2209–2219. doi: 10.1185/030079906X148445. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1185/030079906X148445]. [PMID: 17076982]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasper S., Lerman M.N., McQuade R.D., Saha A., Carson W.H., Ali M., Archibald D., Ingenito G., Marcus R., Pigott T. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6(4):325–337. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703003651. [http://dx.doi. org/10.1017/S1461145703003651]. [PMID: 14609439]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedel M., Schennach-Wolff R., Musil R., Dehning S., Cerovecki A., Opgen-Rhein M., Matz J., Seemuller F., Obermeier M., Engel R.R., Muller N., Moller H.J., Spellmann I. Neurocognition and its influencing factors in the treatment of schizophrenia-effects of aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(2):116–125. doi: 10.1002/hup.1101. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hup.1101]. [PMID: 20196179]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travis M.J., Burns T., Dursun S., Fahy T., Frangou S., Gray R., Haddad P.M., Hunter R., Taylor D.M., Young A.H. Aripiprazole in schizophrenia: consensus guidelines. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2005;59(4):485–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00498.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00498.x]. [PMID: 15853869]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Sayeh H.G., Morganti C. Aripiprazole for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006;(2):CD004578. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004578.pub3. [PMID: 16625607]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter R.H., Joy C.B., Kennedy E., Gilbody S.M., Song F. Risperidone versus typical antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003;(2):CD000440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000440. [PMID: 12804396]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbody S.M., Bagnall A.M., Duggan L., Tuunainen A. Risperidone versus other atypical antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2000;(3):CD002306. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002306. [PMID: 10908551]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heres S., Davis J., Maino K., Jetzinger E., Kissling W., Leucht S. Why olanzapine beats risperidone, risperidone beats quetiapine, and quetiapine beats olanzapine: an exploratory analysis of head-to-head comparison studies of second-generation antipsychotics. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014;16(3):185–199. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.185. [PMID: 16449469]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Association A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th text revision ed. 2000. pp. 553–557. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G.C. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–33. [PMID: 9881538]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munetz M.R., Benjamin S. How to examine patients using the abnormal involuntary movement scale. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(11):1172–1177. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.11.1172. [PMID: 2906320]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson G.M., Angus J.W. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [http:// dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x]. [PMID: 4917967]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/13.2.261]. [PMID: 3616518]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guy W. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. 1976.

- 29.Lingjaerde O., Ahlfors U., Bech P. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotrophic drugs and a cross sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic treatment patients. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1987;76:81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447. 1987.tb10566.x]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potkin S.G., Saha A.R., Kujawa M.J., Carson W.H., Ali M., Stock E., Stringfellow J., Ingenito G., Marder S.R. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):681–690. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.681. [http://dx. doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.681]. [PMID: 12860772]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCue R.E., Waheed R., Urcuyo L., Orendain G., Joseph M.D., Charles R., Hasan S.M. Comparative effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics and haloperidol in acute schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;189(5):433–440. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.019307. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.019307]. [PMID: 17077434]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dratcu L., Olowu P., Hawramy M., Konstantinidou C. Aripiprazole in the acute treatment of male patients with schizophrenia: effectiveness, acceptability, and risks in the inner-city hospital setting. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2006;2(2):191–197. doi: 10.2147/nedt.2006.2.2.191. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/nedt.2006.2.2.191]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kim C.Y., Chung S., Lee J-N., Kwon J.S., Kim D.H., Kim C.E., Jeong B., Jeon Y-W., Lee M-S., Jun T-Y., Jung H.Y. A 12-week, naturalistic switch study of the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole in stable outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(4):181–188. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832c25d7. PMID: 19412463[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832c25d7]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; de Oliveira I.R., Elkis H., Gattaz W.F., Chaves A., de Sena E.P., de Matos E., Souza F.G., Campos J.A., Bueno J.R., Silva J.A., LouzA M.R., de Abreu P.B. Aripiprazole for patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an open-label, randomized, study versus haloperidol. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(2):93–102. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900000249. PMID: 19451828[http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ S1092852900000249]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Daniel D.G., Currier G.W., Zimbroff D.L., Allen M.H., Oren D., Manos G., McQuade R., Pikalov A.A., III, Crandall D.T. Efficacy and safety of oral aripiprazole compared with haloperidol in patients transitioning from acute treatment with intramuscular formulations. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2007;13(3):170–177. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000271658.86845.81. PMID: 19238124[http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.pra.0000271658.86845.81]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kinon B.J., Stauffer V.L., Kollack-Walker S., Chen L., Sniadecki J. Olanzapine versus aripiprazole for the treatment of agitation in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(6):601–607. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818aaf6c. PMID: 17522560[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818 aaf6c]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fleischhacker W.W., McQuade R.D., Marcus R.N., Archibald D., Swanink R., Carson W.H. A double-blind, randomized comparative study of aripiprazole and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;65(6):510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.033. PMID: 19011427[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.033]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kane J.M., Osuntokun O., Kryzhanovskaya L.A., Xu W., Stauffer V.L., Watson S.B., Breier A. A 28-week, randomized, double-blind study of olanzapine versus aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70(4):572–581. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04421. PMID: 18986646[http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04421]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kerwin R., Millet B., Herman E., Banki C.M., Lublin H., Pans M., Hanssens L., L ?(tm)Italien G., McQuade R.D., Beuzen J-N. A multicentre, randomized, naturalistic, open-label study between aripiprazole and standard of care in the management of community-treated schizophrenic patients Schizophrenia Trial of Aripiprazole: (STAR) study. Eur. Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.002. PMID: 19323965[http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.002]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chrzanowski W.K., Marcus R.N., Torbeyns A., Nyilas M., McQuade R.D. Effectiveness of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic, stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2006;189(2):259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0564-3. PMID: 17555947[http:// dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0564-3]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zimbroff D., Warrington L., Loebel A., Yang R., Siu C. Comparison of ziprasidone and aripiprazole in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, 4-week study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(6):363–370. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32816f7779. PMID: 17058105[http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0b013e32816f7779]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Leucht S., Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., Corves C., Hunger H., Schmid F., Asenjo Lobos C., Schwarz S., Davis J.M. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):152–163. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030368. PMID: 17917555[http:// dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030368]. [PMID: 19015230]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kane J.M., Carson W.H., Saha A.R., McQuade R.D., Ingenito G.G., Zimbroff D.L., Ali M.W. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):763–771. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0903. [http://dx.doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v63n0903]. [PMID: 12363115]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sussman N. Review of atypical antipsychotics and weight gain. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl. 23):5–12. [PMID: 11603886]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanssens L., L ?(tm)Italien G., Loze J-Y., Marcus R.N., Pans M., Kerselaers W. The effect of antipsychotic medication on sexual function and serum prolactin levels in community-treated schizophrenic patients: results from the Schizophrenia Trial of Aripiprazole (STAR) study ( NCT00237913). BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):95. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-95. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-95]. [PMID: 19102734]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halbreich U., Kinon B.J., Gilmore J.A., Kahn L.S. Elevated prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia: mechanisms and related adverse effects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(Suppl. 1):53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00112-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(02) 00112-9]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shim J-C., Shin J-G., Kelly D.L., Jung D-U., Seo Y-S., Liu K-H., Shon J-H., Conley R.R. Adjunctive treatment with a dopamine partial agonist, aripiprazole, for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: a placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1404–1410. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071075. PMID: 12504072[http://dx.doi. org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071075]. [PMID: 17728426]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolan R., Fletcher P., Frith C., Friston K., Frackowiak R., Grasby P. Dopaminergic modulation of impaired cognitive activation in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Vogt B.A., Pandya D.N., Rosene D.L. Cingulate cortex of the rhesus monkey: I. Cytoarchitecture and thalamic afferents. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;262(2):256–270. doi: 10.1002/cne.902620207. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ cne.902620207]. [PMID: 3624554]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]