Abstract

Autoimmunity appears to play a role in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) pathology. Although the chemokine CCL20 has been involved in autoimmune diseases, its relationship with the pathogenesis of AAA is unclear. We investigated CCL20 expression in AAA and evaluated it as a potential biomarker for AAA. CCL20 was measured in plasma of AAA patients (n = 96), atherosclerotic disease (AD) patients (n = 28) and controls (n = 45). AAA presence was associated with higher plasma levels of CCL20 after adjustments for confounders in the linear regression analysis. Diagnostic performance of plasma CCL20 was assessed by ROC curve analysis, AUC 0.768 (CI:0.678–0.858; p<0.001). Classification and regression tree analysis classified patients into two CCL20 plasma level groups. The high-CCL20 group had a higher number of AAA than the low-CCL20 group (91% vs 54.3%, p< 0.001). mRNA of CCL20 and its receptor CCR6 were higher in AAA (n = 89) than in control aortas (n = 17, p<0.001). A positive correlation was found between both mRNA in controls (R = 0674; p = 0.003), but not in AAA. Immunohistochemistry showed that CCR6 and CCL20 colocalized in the media and endothelial cells. Infiltrating leukocytes immunostained for both proteins but only colocalized in some of them. Our data shows that CCL20 is increased in AAA and circulating CCL20 is a high sensitive biomarker of AAA

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a progressive focal dilatation and weakening of the abdominal aorta, being the most common arterial aneurysm. AAA affects a high percentage of the aged population in industrialized countries. AAA is a complex multifactorial disease with genetic and environmental risk factors1. The disease is progressive, with growth and even rupture2. Mortality from ruptured AAA is as high as 90%3 and currently open surgery or endovascular repair are the unique available treatment for.

AAA is characterized by chronic inflammation, apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells and neovascularisation. Extracellular matrix degradation, microcalcification and oxidative stress are biological processes that contribute to the degeneration of the aorta. The concept of autoimmunity should be taken into account in the AAA pathogenesis and progression, although the precise cause of autoimmunity is not known and the sequence of pathological events and their direct contribution to AAA still remain unexplained (reviewed in4,5).

The identification of specific AAA biomarkers that detect high risk patients and monitor disease progression is a challenge. Several serum biomarkers of inflammatory and proteolytic activity have been investigated in patients with AAA including MMPs, interleukins, CRP and other potential mediators such as TNF-α and TIMP-1 that may contribute to connective tissue degradation and collagen and elastin degeneration. However, measurement of plasma concentrations of these biomarkers has not been demonstrated to be of value predicting clinical risk, probably reflecting a lack of sensitivity6,7. Proteomic studies have been useful to find new candidate biomarkers8 but ultimately plasma concentration could represent the activity of the entire vasculature rather than that of small areas of focal vascular injury. This circumstance coupled with the fact that atherosclerosis in most cases co-exists with AAA, limits the sensitivity and specificity of currently proposed AAA biomarkers. Further, identification of new biomarkers could help to find out new pathways involved in the pathophysiology of AAA and thus to discover new targets for pharmacological intervention. Therefore, it is essential to find new, more specific biomarkers for early detection of the disease and risk stratification.

The C-C chemokine CCL20 (chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20) is a chemokine expressed mainly in the lymphatic tissue, lung and liver9–11 produced by cells related with inflammation and autoimmune response such as endothelial cells, neutrophils, natural killer (NK), Th17 cells and B cells among others11–19. It is well established that CCL20 contributes to inflammatory cell recruitment20. This chemokine selectively signals through its receptor CCR6 (C-C chemokine receptor type 6) that was originally described in both lymphoid and not lymphoid tissues11 and is expressed by several leukocyte subsets, including immature dendritic cells (iDC), B cells, T cells (proinflammatory Th17 cells, regulatory Treg cells), NKT cells and neutrophils11,21,22. CCR6 is a key mediator in iDC recruitment during adaptive immune responses23. The involvement of CCL20/CCR6 axis in the autoimmune response is sustained by its relation with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and other autoimmune pathologies17,24–26. However, to date, the exact role of the CCL20/CCR6 axis in the dynamics of the immune system has yet to be elucidated, despite evidence points to a regulatory role in the balance of activation and suppression of immune and autoimmune responses17,24.

The possible contribution of CCL20 to AAA development and progression is currently uncertain. It has been reported an increase in CCL20 levels in plasma samples from AAA patients compared with normal subjects, but the limited number of patients included in this study does not allow to draw definitive conclusions27. In view of the foregoing, we have assessed CCL20 expression in AAA patients and compared its prognostic ability with other proteins, which are already postulated as AAA biomarkers.

Results

Assessment of plasma levels of pro-inflammatory proteins in AAA and atherosclerotic patients

To study plasma levels of CCL20, 96 patients consecutively admitted to the Angiology and Vascular Surgery Service of our hospital from January 2012 to December 2015 with AAA were included. Also, 28 patients admitted during the same period with diagnosis of ischemic pathology of either lower limbs or carotid territory were included (AD).

Table 1 shows the demographic data of patients included in this study. There were significant differences in the percentage of women, diabetics, patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), patients with brain vascular disease (BVD), and antiplatelet drug users between both groups of patients. In order to assess whether these variables were confounders, we first analysed them in each group separately. None of these variables influenced statistically CCL20 plasma levels in either group of patients. Afterwards, multiple linear regression analysis was performed in all patients, using plasma levels of CCL20 (logarithmic transformation to normalize the distribution) as the dependent variable and the presence of AAA, sex, diabetes, PAD, BVD and antiplatelet treatment as independent variables. In this case only the presence or absence of AAA significantly influenced the levels of CCL20 (LOG [CCL20] = −0.993 + (0.574 ∗ sex) − (0.292 ∗ diabetes) − (0.118 ∗ PAD) − (0.437 ∗ BVD) + (0.0582 ∗ Anti-platelet) + (1.107 ∗ AAA presence); N = 124, R = 0.439; P of Coefficients: Constant = 0.021, Sex = 0.131, Diabetes = 0.270, PAD = 0.609, BVD = 0.171, Anti-platelet = 0.817 and AAA presence < 0.001). None of these parameters were then taken into account as confounding variables. In addition to CCL20, we analysed plasma levels of other 15 proteins in AAA and AD patients. Plasma levels data did not fit a normal distribution in any case. Results in Table 2 show that there were no statistically significant differences between both groups of patients regarding plasma levels of IL1-β, RANTES, VEGF, MPO, IL-8, soluble ICAM and IP-10. Levels of CCL20, TNFα, MMP-9, IL-2, IGFBP-1, soluble Fractalkine, IL-10, soluble TWEAK were significantly higher in patients with AAA, whereas plasma levels of MMP-2 were significantly higher in AD patients.

Table 1.

Demographics of individuals included in the plasma levels study.

| AAA | AD | p | Blood donors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 96 | 28 | — | 45 |

| Age (years) | 73.2 ± 7.2 | 71.6 ± 10.3 | 0.499 | 63.0 ± 2.9 |

| Women | 4.2 | 28.6 | <0.001 | 13.3 |

| Aortic diameter (mm) | 64.7 ± 12.2 | — | — | — |

| Dyslipidemia | 52.1 | 46.4 | 0.752 | 2.2 |

| HTN | 79.2 | 89.3 | 0.350 | 31.1 |

| Diabetes | 20.8 | 46.4 | 0.014 | 2.2 |

| Smokers | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.804 | 13.3 |

| PAD | 43.8 | 75.0 | 0.007 | 0.0 |

| BVD | 9.4 | 39.3 | <0.001 | 0.0 |

| IHD | 28.1 | 32.1 | 0.862 | 0.0 |

| COPD | 16.7 | 7.1 | 0.335 | 0.0 |

| Antiplatelet users | 62.5 | 96.4 | 0.001 | 0.0 |

| Statin users | 72.9 | 85.7 | 0.254 | 15.6 |

| NSAID users | 1.04 | 0.0 | 0.509 | 0.0 |

| Corticoid users | 2.1 | 10.7 | 0.137 | 0.0 |

| Immuno-supressors users | 3.1 | 3.6 | 0.633 | 0.0 |

Nominal variables are presented as %. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. p, refers comparison AAA vs AD. BVD, brain-vascular disease; COPD, chronic occlusive pulmonary disease; HTN, chronic hypertension; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Table 2.

Plasma levels of proteins associated with immunoinflammatory response.

| Protein | Protein levels (pg/mL) | Ratio | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAA n = 96 | AD n = 28 | |||||||

| Median | 25% | 75% | Median | 25% | 75% | |||

| CCL20 | 3.16 | 0.22 | 6.84 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.94 | 28.73 | <0.001 |

| TNFα | 7.06 | 1.475 | 13.677 | 1.41 | 0.69 | 2.635 | 5.01 | <0.001 |

| MMP-9 | 49955 | 29082 | 71751 | 15705 | 12138.5 | 26944 | 3.18 | <0.001 |

| IL-2 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 2.16 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 1.92 | 0.004 |

| IGFBP-1 | 3.21 | 2.055 | 8.455 | 2.14 | 1.33 | 4.72 | 1.50 | 0.016 |

| Fractalkine | 37.15 | 26.108 | 63.995 | 25.915 | 14.535 | 35.555 | 1.43 | <0.001 |

| IL-10 | 2.03 | 0.97 | 8.742 | 1.52 | 0.74 | 2.32 | 1.34 | 0.002 |

| TWEAK | 0.58 | 0.422 | 0.957 | 0.465 | 0.35 | 0.585 | 1.25 | 0.007 |

| MMP-2 | 62221 | 45878.25 | 77264.5 | 84112 | 66031.5 | 106996 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| VEGF | 88.47 | 5.912 | 244.965 | 31.23 | 1.835 | 219.51 | 2.83 | n.s. |

| IL1-β | 0.63 | 0.255 | 2.002 | 0.32 | 0.225 | 0.51 | 1.97 | n.s. |

| RANTES | 9776 | 4498.75 | 17181.25 | 7912.5 | 5733.5 | 13704 | 1.24 | n.s. |

| MPO | 14211.9 | 10603.3 | 22032.8 | 14109.9 | 10312.626 | 19054.9 | 1.01 | n.s. |

| IP-10 | 483.09 | 372.102 | 644.22 | 478.725 | 378.285 | 1019 | 1.01 | n.s. |

| IL-8 | 3.35 | 2.115 | 6.345 | 3.395 | 2.28 | 5.35 | 0.99 | n.s. |

| ICAM | 81204 | 58957 | 144202.25 | 88842.5 | 74749 | 106742 | 0.91 | n.s. |

Plasma levels of proteins associated with inmunoimmflamatory response were determined in aneurysmal patients (AAA) and patients with atherosclerotic disease (AD). Data did not fit a normal distribution and are expressed as the median with 25 and 75 percentiles. Ratio: median AAA/median AD.

We then performed a multiple logistic regression analysis considering occurrence of AAA as depending dichotomous variable. We included in the study those proteins that were increased in AAA more than two-fold in terms of the median, namely CCL20, TNFα and MMP-9 (see Table 2). There was a statistically correlation between plasma levels of CCL20 and TNFα (R = 0.369, p = 2.5·10−4, n = 95) and MMP-9 (R = 0.351, p = 4.9·10−4). We then included plasma levels of CCL20, TNFα and MMP-9 as independent variables. Results of the analysis produces the function Logit P = −0.791 + 1.736 ∗ log [CCL20] + 0.0239 ∗ log [TNF] + 0.368 ∗ log [MMP9] (brackets indicate plasma concentration in pg/mL). Details of the Logistic Regression Equation were: [CCL20] coefficient: Wald statistics 6.550 (p = 0.01) and an odds ratio of 5.7 (CI 1.5–21.5); [TNFα] coefficient: Wald statistics 0.00087 (p = 0.976) and an odds ratio of 1.024 (CI 0.21–5.03); for [MMP-9] coefficient: Wald statistics 0.337 and an odds ratio of 1,45 (CI 0.42–5.01). Consequently CCL20 was the only protein later considered in the study.

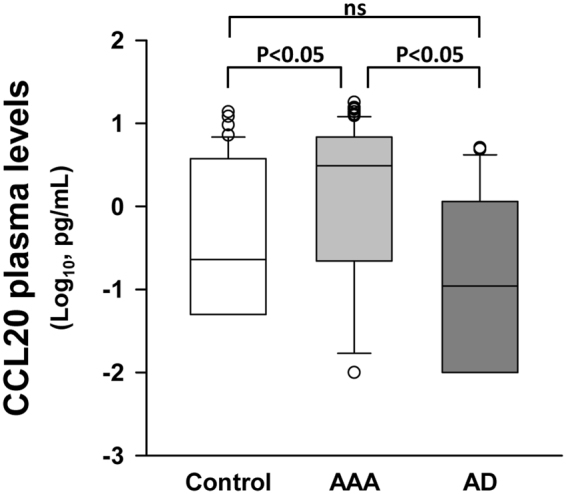

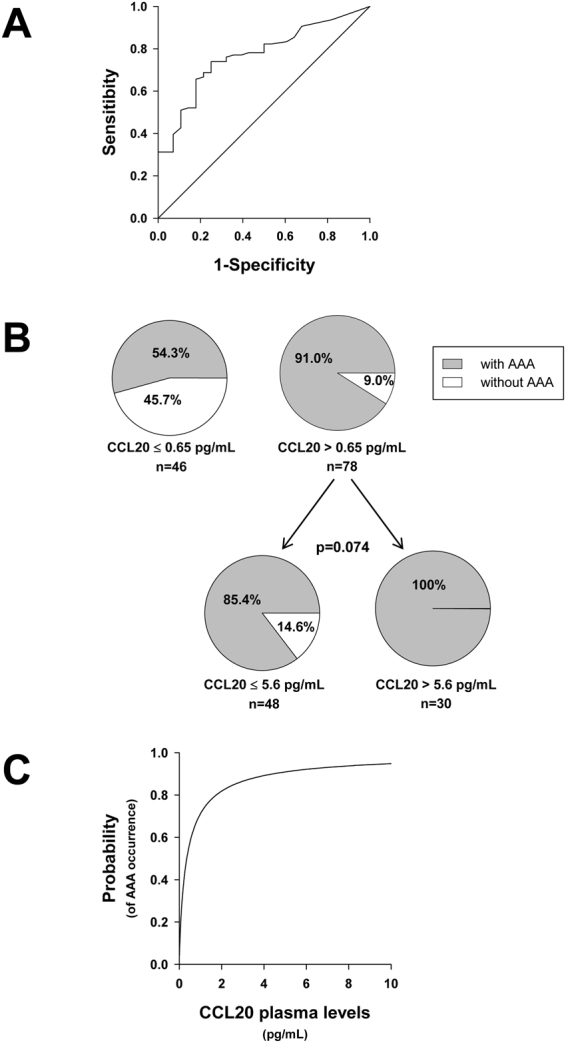

Enhanced CCL20 expression in plasma of AAA patients

Figure 1 shows that CCL20 plasma levels of AAA patients were significantly higher than those of AD and healthy individuals (control). Interestingly, there were no statistically significant differences in CCL20 plasma levels between AD patients and healthy individuals. In view of these results, we analysed CCL20 levels through the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve including AAA and AD patients. The area under the curve (AUC) for CCL20 was 0.768 (CI 0.678–0.858; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Using AAA condition as the dependent variable, we performed classification and regression tree (CART) analysis and patients were classified into two categories, low (≤0.65 pg/mL) and high (>0.65 pg/mL) plasma level of CCL20 (Fig. 2B). The low plasma CCL20 group included 54.3% of AAA patients while the high CCL20 group was constituted by a significantly higher percentage of AAA patients (91%, p < 0.001). In turn, CART analysis divided the high CCL20 group into two categories ≤ 5.6 pg/mL and >5.6 pg/mL (Fig. 2B). Although the difference in the percentage of patients with AAA did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.074), it is noteworthy that the 100% of patients with CCL20 levels >5.6 pg/mL had AAA. Logistic regression analysis, considering [CCL20] as independent variable and occurrence of AAA as the dependent dichotomous variable, yields the following equation Logit P = 0.901 + 2.006 ∗ log10 [CCL20] ([CCL20] coefficient p < 0.001). Calculating the probability of having AAA for the two cut-offs we obtained 62.8% for 0.65 pg/mL and 91.7% for 5.6 pg/mL. The graph showing the calculated probability of AAA occurrence as a function of CCL20 plasma concentration is depicted in Fig. 2C.

Figure 1.

CCL20 plasma concentration in healthy subjects (n = 45), abdominal aortic aneurysm patients (AAA, n = 96) and patients with atherosclerotic disease and without AAA (AD, n = 28). No group fit normal distribution; ns, means no significant differences (p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

(A) Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve for CCL20 plasma levels in abdominal aortic aneurysm patients (AAA, n = 96). The area under the curve was 0.768 (CI 0.678–0.858; p < 0.001). (B) CART analysis classification regarding CCL20 plasma levels as independent variable and using AAA condition as the dependent variable; including all patients in the statistics. (C) Calculated probability from the equation Logit P = 0.901 + 2.006 ∗ log10 [CCL20] obtained in the Logistic Regression Analysis, considering CCL20 plasma concentration ([CCL20]) as independent variable and occurrence of AAA as the dependent dichotomous variable ([CCL20] coefficient p < 0.001).

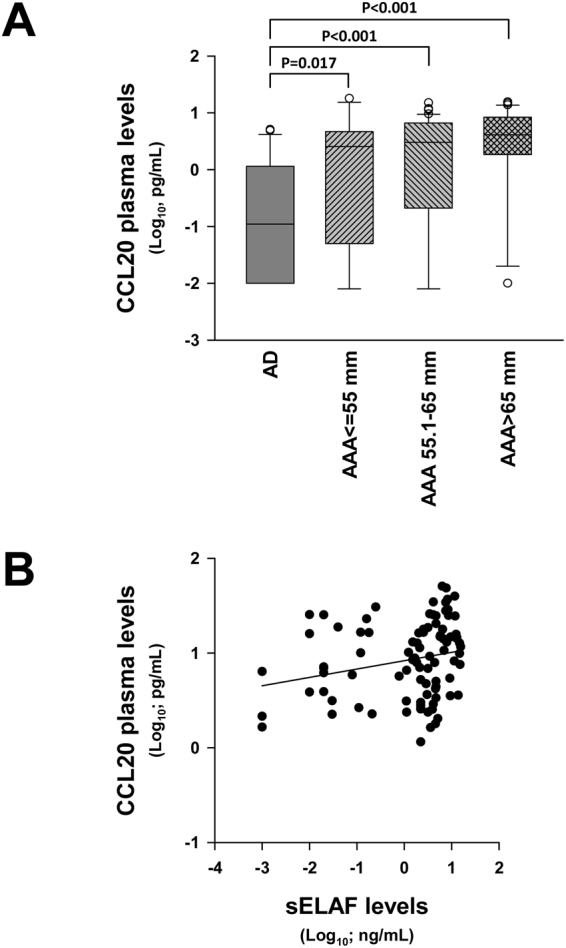

We found no correlation between plasma levels of CCL20 with maximum aneurysm diameter (MD) (not shown). Patients were stratified into three groups according to the MD (MD ≤ 55 mm, 55 < MD ≤ 65 mm and MD >65 mm) and there were no significant differences among the three groups with regards to CCL20 plasma concentration. However, it is noteworthy that even the group of MD ≤ 55 mm had significantly higher level of CCL20 than AD patients (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) CCL20 plasma concentration in abdominal aortic aneurysm patients stratified by MD (AAA) and patients with atherosclerotic disease without AAA (AD). No group fit normal distribution. (B) Statistical correlation of between CCL20 and sELAF in AAA samples.

Since plasma levels of soluble elastin fragments (sELAF) were associated with vascular wall deterioration, we analysed their plasma levels in AAA and AD patients. No significant differences were found in sELAF plasma levels between AAA and AD or correlation between them and MD (data nor shown). However, AAA patients exhibited a poor but significant correlation between CCL20 and sELAF plasma levels (Fig. 3B). When AAA patients were stratified by MD in the same manner as CCL20, no significant differences were observed among the three groups ≤ 55 mm, 55.1–65 mm and > 65 mm regarding sELAF.

CCL20 expression in AAA tissues

Thereafter we quantified CCL20 local expression in AAA aorta tissue samples in terms of mRNA compared with normal aorta. The demographic data of the individuals included in mRNA analysis are shown in Table 3. There were significant differences in age, percentage of women, patients with dyslipemia, hypertension, PAD, ischemic heart disease, antiplatelet drug users and statin users between both groups. The influence of age on the CCL20 local mRNA levels was explored by multiple linear regression analysis after logarithmic transformation of CCL20 mRNA levels. Log10 of CCL20 was considered dependent variable and age and age2 as independent variables. No dependence of CCL20 local expression on age was observed in any of the groups, AAA or normal aorta (AAA: log10 CCL20 = −3.119 + 0.101 ∗ age −0.000758 ∗ age2, age coefficient p = 0.549, age2 coefficient p = 0.523, R = 0.099; Controls: Log10 CCL20 = −1.292 + 0.0297 ∗ age − 0.000326 ∗ age2, age coefficient p = 0.777, age2 coefficient p = 0.739, R = 0.124). No differences in CCL20 local mRNA levels between positive and negative individuals for women, dyslipemia, hypertension, PAD, ischemic heart disease, antiplatelet drug user and statin user in neither normal aorta nor AAA groups were also found. Then, none of these parameters were taken into account as confounding variables for the statistics.

Table 3.

Demographics of individuals included in the local mRNA levels study.

| AAA | Normal Aorta | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 89 | 17 | — |

| Age (years) | 71.0 ± 6.6 | 57.5 ± 15.9 | <0.001 |

| Women | 5.6 | 58.8 | <0.001 |

| Aortic diameter (mm) | 65.0 ± 13.0 | — | — |

| Dyslipidemia | 60.7 | 17.6 | 0.003 |

| HTN | 71.9 | 17.6 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 23.6 | 11.8 | 0.447 |

| Smokers | 27.0 | 11.8 | 0.305 |

| PAD | 49.4 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| BVD | 7.9 | 11.8 | 0.957 |

| IHD | 24.7 | 0.0 | 0.048 |

| COPD | 19.1 | 0.0 | 0.108 |

| Antiplatelet users | 59.6 | 11.8 | <0.001 |

| Statin users | 68.5 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| NSAID users | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.843 |

| Corticoid users | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.843 |

| Immuno-supressors users | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.843 |

Nominal variables are presented as %. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. Due to the nature of normal aorta samples some of the clinical characteristics are not always recorded and infra-evaluation of them is probable. BVD, brain-vascular disease; COPD, chronic occlusive pulmonary disease; HTN, chronic hypertension; IHD, ischemic heart disease; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

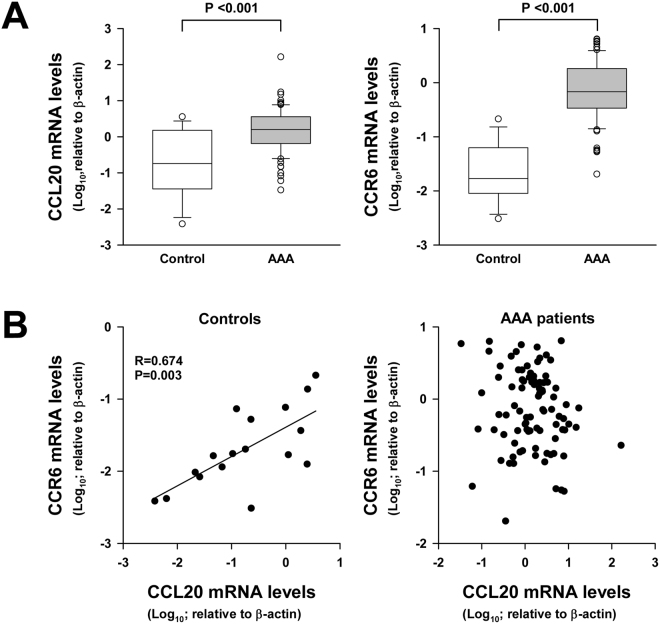

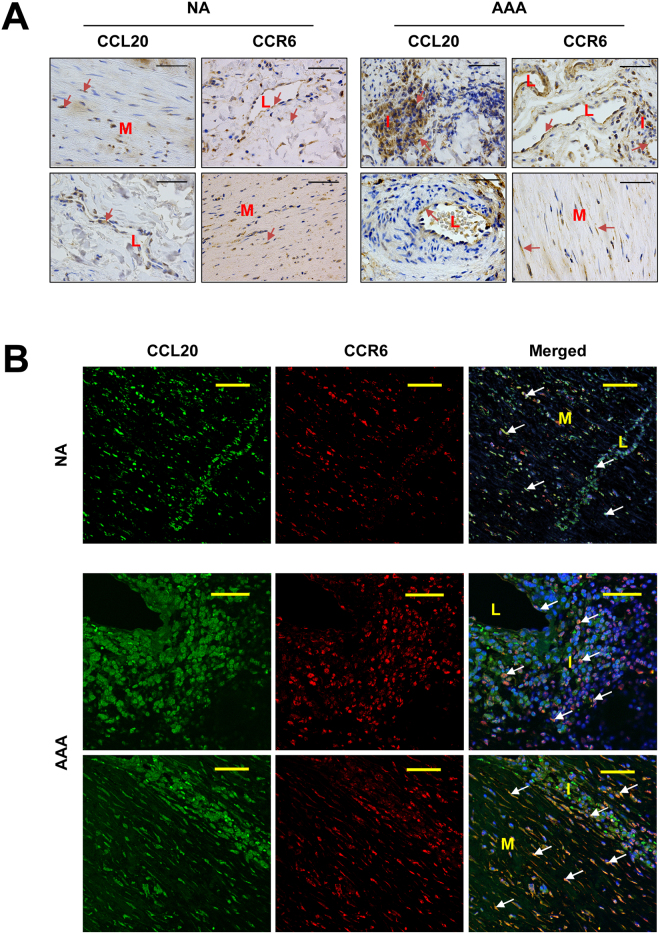

Results depicted in Fig. 4A show that expression of both CCL20 and its receptor CCR6 were significantly higher in AAA samples than in normal aorta. Nevertheless, there was not statistical correlation between CCL20 and CCR6 mRNA expression in AAA samples. In contrast, there was a significant correlation between CCL20 and CCR6 local expression in normal aorta samples (R = 0674; p = 0.003, Fig. 4B). Immunohistochemical studies showed that CCR6 and CCL20 were widely expressed in normal aorta, in the medial layer and endothelial cells from the microvasculature in which they were often co-expressed (Fig. 5A and B). Further, in aneurysmatic samples CCL20 and CCR6 were also abundantly expressed by infiltrating leukocytes. However, and consistently with correlation studies, such co-expression did not occur in all infiltrating leukocytes and only few cells were clearly positive for both proteins (Fig. 5B).

Figure 4.

(A) CCL20 and its receptor (CCR6) transcription levels in normal aorta from healthy donors (control, n = 17) and abdominal aortic aneurysm lesions (AAA, n = 89). No group fit normal distribution. (B) Statistical correlation between CCL20 and its receptor transcription levels in normal aortas (control) and AAA samples.

Figure 5.

(A) Representative immunohistochemistry images of CCL20 and its receptor (CCR6) in normal aorta (NA) and in AAA samples. Arrows show some immunostained cells. (B) Representative immunofluorescent double staining for CCL20 and CCR6 in normal aorta (NA) and in AAA samples. Arrows show double immunostained cells. Bars are 50 µm; L, indicates the light of microvessels; I, indicates leukocyte infiltration areas; and M, indicates media layer.

Discussion

AAA is a multifactorial disease with genetic and environmental risk factors. AAA is an immuno-inflammatory disease associated with atherosclerosis5 and, like other autoimmune pathologies, AAA progressively degenerates until the destruction of normal tissue. CCL20 has been associated with several autoimmune diseases17,24–26 and this fact led us to investigate the association between CCL20 and AAA.

Here, we comparatively investigated the expression of the CCL20/CCR6 system in AAA as well as in non-AAA atherosclerotic patients and healthy individuals. Our results show that circulating CCL20 is significantly increased in AAA when compared with healthy individuals. Most importantly, CCL20 is also increased when compared with individuals with atherosclerotic vascular pathology without AAA. It should be highlighted that this is a unique feature of CCL20, not observed for other cytokines also increased in the AAA, suggesting that CCL20 is particularly relevant in patients suffering from AAA.

We must point out that unlike other authors27, we found no statistical correlation between the aortic diameter and plasma levels of any of the cytokine tested (results not shown) in aneurysmatic patients. One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be that when we analyzed the statistical correlations of MD and plasma levels, only patients with AAA were taken into account. Particularly, we did not find a statistical correlation between the aortic maximum diameter and plasma levels of CCL20. If we assume that the aortic diameter somehow represents the chronology of AAA and considering that CCL20 is significantly higher even in patients with the smallest diameter, our results suggest that CCL20 is increased from the early stages of the disease. The lack of correlation between plasma concentration of CCL20 and the aortic diameter is not surprising since, in our view, plasma levels of a chemokine reflect a systemic immune situation while the aortic diameter might reflect the evolution of the injury. A priori, there is no reason in our view, to suppose a correlation between systemic levels of a protein involved in the immune response measured in a particular moment with the degree of evolution of a related injury. Presumably, the extent of injury depends on how long tissue states under inflammatory condition rather than at a given time concentration of a specific immune mediator in that tissue and still less likely on its plasma levels. Indeed, some inflammatory mediators reach a maximum in patients with intermediate MD and then decreases at higher MD28–31. Another issue is the relationship of plasma levels with the rate of progression of the injury that is probably strictly related to the intensity of the immune response. In this regard we have not measured the AAA growth rate, which is a limitation of the present study. However, we found a significant correlation between CCL20 and sELAF, which is related to the degradation of the vascular wall and exhibit pro-inflammatory activity32.

In addition, we observed that CCL20 levels are a sensitive marker for AAA, CCL20 high levels are associated with AAA presence. The statistical study shows that plasma concentrations above 5.6 pg/mL imply a likelihood of AAA higher than 90%.

Both atherosclerosis and AAA are diseases characterized by a great inflammatory infiltrate. However, our results reveal that significant differences exist regarding factors involved in the recruitment of immune-inflammatory cells to the aortic wall and their local activation between these two disorders.

We also report a significant CCL20/CCR6 up-regulation in AAA tissues compared to normal aortic tissues. It is noteworthy that in normal aortas local CCL20 expression correlates with the expression of its receptor CCR6, which is not the case in AAA samples. Immunohistochemical studies revealed that both proteins were expressed by vascular cells, while only part of the massive inflammatory infiltrate in AAA samples co-expresses CCL20 and its receptor. This could explain why correlation between CCL20 and its receptor could only be observed in normal aorta.

In summary, we showed that plasma concentration of CCL20 was significantly higher in patients with AAA when compared with healthy individuals and, more importantly, with patients having atherosclerotic pathology without AAA. The statistical analysis shows that CCL20 plasma levels predict with high sensitivity the presence of AAA. CCL20 was also overexpressed in patients with AAA in terms of local transcript levels compared with healthy individuals. The role and the nature of the immune-mediated mechanisms in AAA have recently started to be addressed4,5. The present study shows an association of CCL20 with AAA, but the role of CCL20 in the pathogenesis and progression of AAA still remains uncertain. To asses this point, further research is needed.

Material and Methods

Patients

The study was approved by the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau Ethics Committee (13/103/1491), and patients gave written informed consent prior to surgery. The study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical outcomes were taken from the clinical database.

We defined two groups of patients as follows, patients with AAA and patients with atherosclerotic disease without AAA (AD). Inclusion criteria of AAA group were patients undergoing elective open or endovascular repair for atherosclerotic AAA. Exclusion criteria were patients with pseudoaneurysms, or infectious or inflammatory aneurysms. When possible an infrarenal aorta biopsy was taken during the intervention. All AAA patients underwent surgery at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. AD group was constituted by patients admitted during the same period in our centre with ischemic pathology diagnosis of either lower limbs or carotid territory. Patients with aortic or peripheral aneurismal pathology were excluded from this group. Blood was collected before anaesthesia in the operating room. A sample of 10 mL of peripheral blood was collected from the individuals in heparin-containing tubes. It was centrifuged immediately and plasma aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C until CCL20 analysis.

Tissue samples

Biopsies were systematically performed on the anterolateral wall of the remaining mid-infrarenal aortic wall after the exclusion and prosthetic replacement of AAA, at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. Intraluminal thrombi, if present, were separated before the aorta biopsy was taken. Normal aortas (Controls) were obtained from healthy aorta from multiorgan donors and samples were also taken from the mid-portion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta at organ harvest. Biopsies were processed immediately, a portion of each sample was placed in RNAlater solution (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and stored for 24 hours at 4 °C before long-term storage at −80 °C until further processing for RNA isolation.

Risk factors

The definition of the risk factors used in this study were: diabetes mellitus: glycated haemoglobin >5.8% or use of oral antidiabetic drugs or insulin; arterial hypertension: systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg or use of antihypertensive medication; dyslipidemia: a total cholesterol >6.2 mmol/L, LDL cholesterol >4.13 mmol/L, HDL cholesterol < 1 mmol/L or triglycerides >1.65 mmol/L; smoking was categorized into 2 groups: smokers: smokers and ex-smokers stopped smoking < 1 year, and non-smokers: never-smoked and ex-smokers stopped smoking >1 year; COPD: FEV1/FVC < 0.7, brain-vascular disease: history of stroke, transient ischemic attack or major neurological deficit; ischemic heart disease: history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris or previous coronary intervention; peripheral artery disease: including any stage of Fontaine classification or previous revascularization intervention or ischemic amputation.

RNA extraction and mRNA analysis

Tissues were homogenized in the FastPrep-24 homogenizer and Lysing Matrix D tubes (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared by reverse transcribing 1 µg RNA with the High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit with random hexamers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). mRNA levels of CCL20 and CCR6 were studied by real-time PCR in an ABI Prism 7900HT using pre-designed validated assays (TaqMan Gene Expression Assays; Applied Biosystems) and universal thermal cycling parameters. Relative expression was expressed as transcript/β-actin ratios.

Plasma measurements

CCL20, IL1-β, RANTES, VEGF, MPO, IL-8, soluble ICAM, IP-10, CCL20, TNFα, MMP-9, IL-2, IGFBP-1, soluble Fractalkine, IL-10 and soluble TWEAK protein levels in plasma were analyzed in a Luminex using xMAP® technology (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), and sELAF levels were analyzed using ELISA (MyBiosource, San Diego, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies were performed using a goat polyclonal antibody against human CCL20 (diluted 1:100) and a mouse monoclonal anti human CCR6 (diluted 1:200) both from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Three-micrometer sections of paraffin-embedded tissue samples were stained in a Dako Autostainer Link 48 using the Dako EnVision Flex Kit. Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen.

Double immunofluorescence

For co-localization studies, double immunofluorescence staining was performed. After deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval, blocking for unspecific binding was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. A mixture of two primary antibodies, CCL20 and CCR6, in 1% BSA was then applied for 1 hour at room temperature, After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with a mixture of two secondary antibodies in 1% BSA for 1 hr at room temperature in dark (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated rabbit-antigoat IgG (H + L) and biotinylated horse-antimouse IgG (H + L) both diluted 1/250, Invitrogen, Life Technologies Co, Eugene, OR) followed by 45 minutes incubation with Streptavidin protein Alexa Fluor 594. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 for 10 minutes. As a negative control, sections were incubated omitting primary antibodies. Samples were then mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies Co). Images were obtained using an SP5 Leica confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

SPSS and Sigma-Plot software were used for statistical analysis. To evaluate the statistical differences in the demographic variables between two groups the t-test was used for those continuous variables that fit a normal distribution and Mann-Whitney U test for those continuous variables that did not have a normal distribution. To observe differences in the demographic dichotomous variables between two groups we used z-test. Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks was used to compare CCL20 levels in more than two groups since they did not fit normal distribution. Spearman Rank Order Correlation was used for correlation between variables. Multiple linear regression was used to study the association of CCL20 plasma levels with quantitative demographic variables and multiple logistic regression was used to study the likelihood of the occurrence of AAA as a function of CCL20 plasma levels. We used ROC curves to evaluate capacity of CCL20 to discriminate between AAA and AD patients. Continuous value parameters were analyzed using a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis, considering AAA condition as a dependent variable. The CART analysis split the continuous data into segments that were as heterogeneous as possible, according to the dependent variable. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Sonia Alcolea for her technical support. This study was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), SAF2013-46707-R and SAF2015-64767-R and from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, PI15/01016 and CIBERCV. The study was co-founded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Supported by CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author Contributions

B.S. collected human samples, analyzed data and provided intellectual input. T.G.-M. performed plasma measurements and the immunohistochemical studies, analyzed data and provided intellectual input. C.R., J.M.-G. edited and contributed to the discussion of the paper and provided intellectual input. J.-R.E. collected human samples, critically revised the intellectual content. L.V. concept and design the study, performed the statistics analysis and interpretation of data and wrote/edit the paper. M.C. performed RNA studies, design the study, analysis and interpretation of data and wrote/edit the paper. All authors read and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnston KW, et al. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms, Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13:452. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.26737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stather PW, et al. Meta-analysis and meta-regression análisis of biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1358–1372. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moxon JV, et al. Diagnosis and monitoring of abdominal aortic aneurysm: current status and future prospects. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:512–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuivaniemi H, Platsoucas CD, Tilson MD., III Aortic aneurysms: an immune disease with a strong genetic component. Circulation. 2008;117:242–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuivaniemi H, Ryer EJ, Elmore JR, Tromp G. Understanding the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:975–987. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1074861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urbonavicius S, et al. Potential circulating biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion and rupture—a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golledge J, Tsao PS, Dalman RL, Norman PE. Circulating markers of abdominal aortic aneurysm presence and progression. Circulation. 2008;118:2382–2392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bylund D, Henriksson AE. Proteomic approaches to identify circulating biomarkers in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;5:140–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hromas R, et al. Cloning and characterization of exodus, a novel beta-chemokine. Blood. 1997;89:3315–3322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hieshima K, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine liver and activationregulated chemokine (LARC) expressed in liver. Chemotactic activity for lymphocytes and gene localization on chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5846–5853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schutyser E, Struyf S, Van Damme J. The CC chemokine CCL20 and its receptor CCR6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:409–426. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hromas R, et al. Isolation and characterization of Exodus-2, a novel C-C chemokine with a unique 37-amino acid carboxyl-terminal extension. J Immunol. 1997;159:2554–2558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meissner A, et al. CC chemokine ligand 20 partially controls adhesion of naive B cells to activated endothelial cells under shear stress. Blood. 2003;102:2724–2727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriehuber E, et al. Isolation and characterization of dermal lymphatic and blood endothelial cells reveal stable and functionally specialized cell lineages. J Exp Med. 2001;194:797–808. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scapini P, et al. Neutrophils produce biologically active macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha (MIP-3alpha)/CCL20 and MIP-3beta/CCL19. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1981–1988. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<1981::AID-IMMU1981>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella M, et al. A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature. 2009;457:722–725. doi: 10.1038/nature07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamazaki T, et al. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:8391–8401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowman EP, et al. Developmental switches in chemokine response profiles during B cell differentiation and maturation. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1303–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu Y, et al. CC-chemokine receptor 6 and its ligand macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha might be involved in the amplification of local necroinflammatory response in the liver. Hepatology. 2001;34:311–319. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caux C, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell recruitment by chemokines. Transplantation. 2002;15:S7–11. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200201151-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Connett JM, Kunkel SL. CCR6 as a mediator of immunity in the lung and gut. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee AY, Eri R, Lyons AB, Grimm MC, Korner HCC. Chemokine Ligand 20 and Its Cognate Receptor CCR6 in Mucosal T Cell Immunology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Odd Couple or Axis of Evil? Front Immunol. 2013;4:194. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dieu MC, et al. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188:373–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comerford I, et al. An immune paradox: how can the same chemokine axis regulate both immune tolerance and activation?: CCR6/CCL20: a chemokine axis balancing immunological tolerance and inflammation in autoimmune disease. Bioessays. 2010;32:1067–1076. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stahl EA, et al. BIRAC Consortium; YEAR Consortium. Genomewide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:508–514. doi: 10.1038/ng.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedrick MN, Lonsdorf AS, Hwang ST, Farber JM. CCR6 as a possible therapeutic target in psoriasis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:911–922. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.504716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos-Mozo P, et al. Plasma profiling by a protein array approach identifies IGFBP-1 as a novel biomarker of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freestone T, et al. Inflammation and matrix metalloproteinases in the enlarging abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1145–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.15.8.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMillan WD, et al. The relationship between MMP-9 expression and aortic diameter. Circulation. 1997;96:2228–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.7.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camacho M, et al. Microvascular COX-2/mPGES-1/EP-4 axis in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:3506–3515. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M042481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dilmé JF, et al. Influence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Levels of Matrix Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48:374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duca L. el al. Matrix ageing and vascular impacts: focus on elastin fragmentation. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:2998–308. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]