Abstract

Objective: Aggression is among the most common indications for referral to child and adolescent mental health services and is often challenging to treat. Understanding the biological underpinnings of aggression could help optimize treatment efficacy. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), specifically the α7 nAChR, encoded by the gene CHRNA7, have been implicated in aggressive behaviors in animal models as well as humans. Copy number variants (CNVs) of CHRNA7 are found in individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders, often with comorbid aggression. In this study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of CHRNA7 CNVs among individuals treated with risperidone, predominantly for irritability and aggression.

Methods: Risperidone-treated children and adolescents were assessed for CHRNA7 copy number state using droplet digital PCR and genomic quantitative PCR. Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical data, including the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), were collected and compared across individuals with and without the CHRNA7 deletion.

Results: Of 218 individuals (90% males, mean age: 12.3 ± 2.3 years), 7 (3.2%) were found to carry a CHRNA7 deletion and one proband carried a CHRNA7 duplication (0.46%). T-scores for rule breaking, aggression, and externalizing behavior factors of the CBCL were higher in the deletion group, despite taking 58% higher dose of risperidone.

Conclusions: CHRNA7 loss may contribute to a phenotype of severe aggression. Given the high prevalence of the deletion among risperidone-treated youth, future studies should examine the therapeutic potential of α7 nAChR-targeting drugs to target aggression associated with CHRNA7 deletions.

Keywords: : CHRNA7, 15q13.3 microdeletion, aggression, disruptive behaviors, risperidone

Introduction

Maladaptive aggressive and disruptive behavior (referred to as aggression, hereafter) is one of the most common indications for referrals to mental health services. It is observed across a wide range of disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), psychotic disorders, and mood disorders (Jensen et al. 2007; Farmer and Aman 2011; Zahrt and Melzer-Lange 2011). Practice guidelines recommend psychotherapeutic interventions as a first-line intervention, followed by the use of psychotropics for severe or persistent aggression (Jensen et al. 2007; Steiner and Remsing 2007). Given the challenges in successfully treating chronic aggression (Jensen et al. 2007), understanding its biological underpinnings could help optimize treatment efficacy.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are a family of complex ligand-gated ion channels in the brain (α1–α7, α9, and β2–β4), each with slightly different pharmacological, kinetic, and signaling properties (Shen and Yakel 2009). They have been implicated in aggression in both humans and animal models. In fact, nicotine withdrawal has been found to worsen aggression in humans, whereas transdermal nicotine administration improves it in individuals with severe dementia or ASD (Picciotto et al. 2015). In particular, the α7 nAChR, encoded by the gene Chrna7, has been identified as a modulator of aggressive behavior in mice, although other pathways are certainly implicated (Lewis et al. 2015; Picciotto et al. 2015). In humans and mice, CHRNA7 (Chrna7 in mice) is highly expressed in the brain, particularly in the hippocampus along with other areas implicated in aggression, including the amygdala (Lewis et al. 2015). In addition, treatment with α7 nAChR agonists reduces physical aggression in mice, again highlighting its role in modulating aggression (Lewis et al. 2015).

CHRNA7 is located at chromosome 15q13.3, a highly unstable region of the genome with an inherent propensity for copy number variants (CNVs). Thus, it is included in recurrent 15q13.3 CNVs that result in a wide range of neuropsychiatric phenotypes in humans, including aggression (Gillentine and Schaaf 2015). This is particularly true for those carrying heterozygous deletions, termed 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome (OMIM 612001), where up to half of the probands described in the literature have exhibited aggression (Miller et al. 2009; Shinawi et al. 2009; van Bon et al. 2009; Vu et al. 2011). This offers a unique potential therapeutic opportunity given that nAChR agonists and positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) have been evaluated in humans (Cubells et al. 2011; Olincy et al. 2016; Gee et al. 2017). In fact, galantamine, a nonspecific nAChR PAM and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, has been found effective for mitigation of aggression in a Case Report of a proband with a 15q13.3 deletion and rage outbursts (Cubells et al. 2011).

To determine the extent to which CHRNA7 contributes to non-syndromic aggression, we performed droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) to assess the copy number state of CHRNA7 in a cohort of risperidone-treated children and adolescents. Additionally, clinical characteristics were compared across those with and without CHRNA7 deletions.

Methods

Participants

Data from four studies were combined to maximize sample size (n = 218) (Calarge et al., 2014; Calarge et al. 2015a, 2015b; Calarge and Schlechte 2017). Three studies included children and adolescents who had been taking risperidone for at least 6 or 12 months. The fourth consisted of a prospective observational study that included six children who had initiated treatment with risperidone within the prior month (Bahr et al. 2015). In all four studies, chronic medical or neurological conditions, and concurrent treatment with more than one antipsychotic medication led to exclusion. Notably, participants with ID were also excluded, except from one study, which enrolled a total of seven participants, three of whom had ID (none found to have the CHRNA7 deletion). All studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Board. After study description, written consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians and assent was obtained from the participants.

At study entry, demographic and clinical data were collected (Bahr et al. 2015). The medical and pharmacy records were reviewed to document all psychotropic treatments. A best estimate diagnosis, following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR, Association, 2000), was generated based on a review of the psychiatric record, supplemented by a standardized interview of the parent using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (Shaffer et al. 2000), the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach et al. 2001), and a clinical interview conducted by a child psychiatrist (C.A.C.). CBCL raw scores were converted to normalized T-scores, with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 (Achenbach et al. 2001).

Droplet digital PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes using the Purgene Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or from saliva using the prepIT L2P Kit (DNA Genotek, Ottowa, ON). DNA samples were assayed for CHRNA7 CNVs using ddPCR. No other genetic variants were assessed, other than RPP30, used as a reference control given its stable copy number among humans. Controls with known CHRNA7 copy number state (one copy [deletion], two copies [copy neutral], or three copies [duplication]) were assessed by chromosomal microarray (CMA) analysis and multiplex ligation probe analysis as described previously, and used as positive and negative controls (Ziats et al. 2016; Gillentine et al. 2017).

Fifty nanograms of DNA from each subject was used in duplicate in the ddPCR reaction. First, DNA was digested with HaeIII for 1 hour at 37°C. Digested DNA, PrimePCR ddPCR copy number assay for the reference gene with a HEX fluorophore (RPP30, dHsaCPE5038241; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), PrimePCR ddPCR copy number assay for CHRNA7 with a FAM fluorophore (dHsaCP1000530; Bio-Rad), 2X ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) (Bio-Rad), and up to 20 μL of water were mixed in a Deepwell 96-well plate (Eppendorf). Importantly, the CHRNA7 assay spanned an exon–intron junction at exon 2 that is not shared with the human-specific fusion gene, CHRFAM7A, which shares exons 5–10 with CHRNA7. Plates were sealed using the PX1 PCR Plate Sealer (Bio-Rad). Droplets were generated using the QX200 AutoDG Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) with Droplet Generation Oil for Probes (Bio-Rad). PCR was performed using a C1000 touch thermocycler (Bio-Rad) with the following cycle: 95°C 10 minutes; 94°C 30 seconds, 60°C 1 minute (40 cycles); 98°C 10 minutes; 4°C forever.

Droplets were analyzed using the QX200 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad) and the QuantaSoft software (Bio-Rad). In the QuantaSoft software, the fraction of PCR-positive (i.e., fluorescence from the control and CHRNA7 probe) was determined for known control samples, and a Poisson distribution was used to determine the CHRNA7 concentration. This was then compared with the unknown samples to call them as deletions, duplications, or copy neutral.

Genomic quantitative PCR

Identified deletions or duplications were confirmed with an orthogonal method using genomic quantitative PCR (qPCR). PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (IDT, Coralville, IA), control probe (RPPH1; IDT) or CHRNA7 probe (IDT), 10 ng of sample DNA, and up to 20 μL of water were added to 96-well plates in duplicate (Bio-Rad). qPCR was run using the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) with the following cycle: 95°C 3 minutes; 95°C 15 seconds; 60°C 1 minute (35 cycles); 4°C forever. Copy number was compared with controls with known CHRNA7 copy number.

Statistical analysis

Body mass index (BMI) was computed as weight/height2 (kg/m2) and age–sex-specific weight, height, and BMI Z-scores were generated based on the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention normative data (Ogden et al. 2002). One child was removed from statistical analysis due to a confirmed CHRNA7 duplication. The participants were split in two groups based on the presence of CHRNA7 deletion. Comparisons between the two groups were conducted using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Welch's t-test for continuous ones. Using published data, the prevalence of 15q13.3 deletions among presumably healthy control individuals was determined to be 0.02% (Malhotra and Sebat 2012). Regression models were utilized to determine differences in risperidone or methylphenidate-equivalent (MPH) doses, adjusting for relevant covariates. All calculations were performed using SAS v9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Genetics

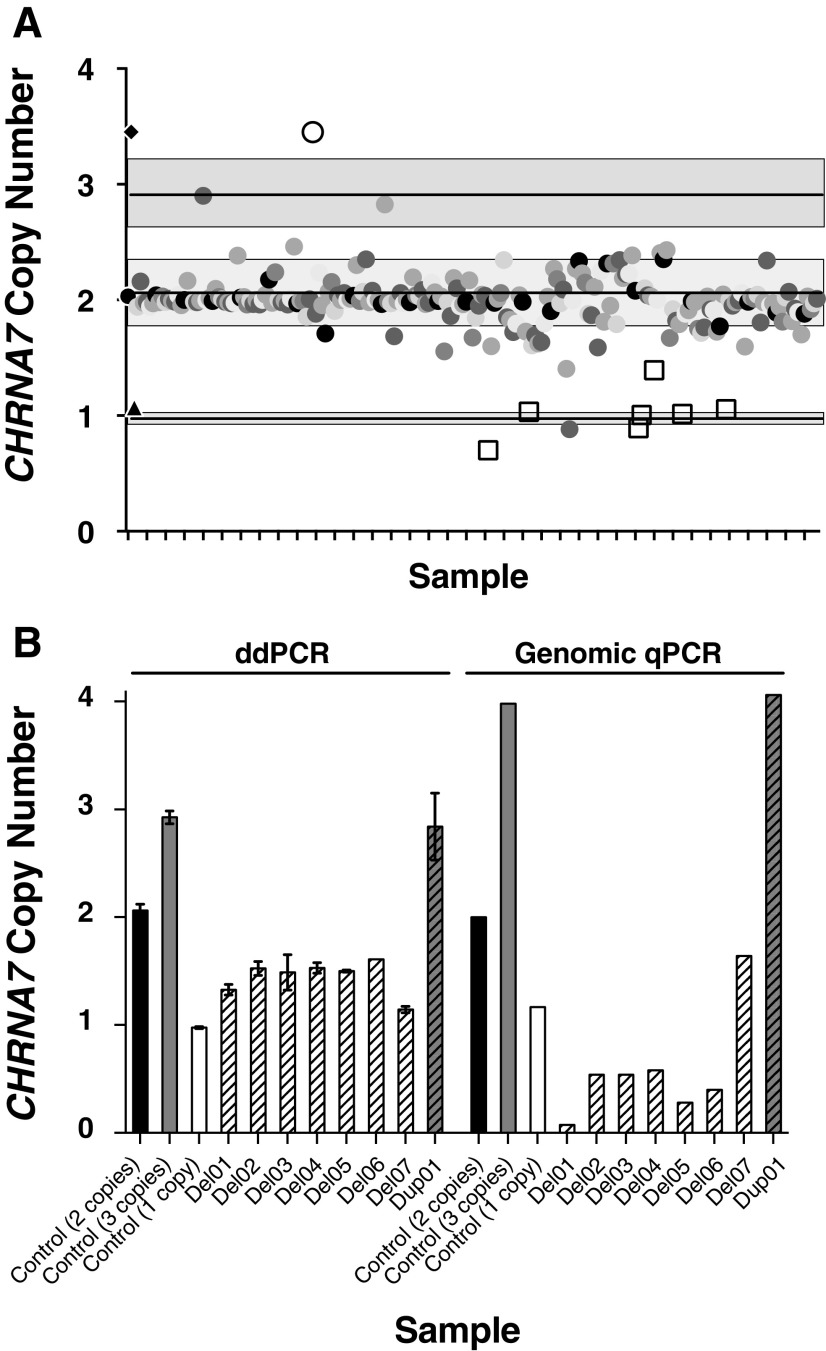

Utilizing ddPCR, samples from 218 individuals were genotyped for CHRNA7 CNVs (Fig. 1A). Four DNA samples were determined to represent CHRNA7 duplications by the ddPCR assay, but three of them were not replicated by genomic qPCR, due to poor quality of the DNA samples. The only proband with genomic qPCR-confirmed duplication had a diagnosis of ADHD and ASD. The rate of duplications in our sample (1/218, 0.46%) is similar to what has been reported in “normal” control populations (0.55%–0.62%) (Gillentine et al. 2017). In addition, 7 of the 218 probands (3.2%) were found to have CHRNA7 deletions, all confirmed using genomic qPCR (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

ddPCR and genomic qPCR genotyping of CHRNA7 copy number. (A) ddPCR results of all aggression samples. Two standard deviations are shown in the grey boxes. Controls for copy neutral (circle), duplication (diamond), and deletion (triangle) are indicated on the Y-axis indicate with lines indicating control copy number. Samples confirmed to be deletions or duplication by genomic qPCR are shown in open squares and open circle, respectively. (B) Samples that were genotyped as CHRNA7 gain or loss by ddPCR and genomic qPCR. Controls are shown in solid colors (black: copy neutral; grey: duplication; white: deletion) and samples are shown with patterned bars in their appropriate color (grey: duplication; white: deletion).

Clinical and anthropometric data

The clinical and demographic data are described in Table 1. Notably, the anthropometric measures in the two groups were different numerically, although not statistically, due to the small number of participants with the deletion. After adjusting for duration of risperidone treatment, weight Z-score remained nonsignificantly different between the two groups (β = −0.51, standard error [SE] = 0.41, p = 0.2216, and Cohen's d = 0.47).

Table 1.

Demographic and Anthropometric Characteristics of 217 Probands (Mean ± Standard Deviation, Unless Noted Otherwise)

| Entire sample, n = 217 | CHRNA7 copy neutral, n = 210 | CHRNA7 deletion, n = 7 | Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 12.3 ± 2.8 | 12.5 ± 3.7 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| Male, n (%) | 195 (80) | 189 (90) | 6 (86) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Weight Z-score | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | ||||

| At risperidone initiationa | 0.11 ± 1.04a | 0.13 ± 1.04 | −0.25 ± 1.13 | NS | |

| At study entry | 0.50 ± 1.09 | 0.52 ± 1.09 | 0.00 ± 0.91 | NS | |

| Changeb | 0.48 ± 0.75 | 0.49 ± 0.76 | 0.26 ± 0.52 | NS | |

| Height Z-score at study entry | 0.13 ± 0.99 | 0.14 ± 0.99 | −0.16 ± 1.05 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| BMI Z-score at study entry | 0.52 ± 1.08 | 0.53 ± 1.08 | 0.07 ± 0.72 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

Does not include CHRNA7 duplication.

Collected from the medical record if measured within a month before or 3 days after risperidone was initiated (n = 162).

Change in weight Z-score between the onset of risperidone treatment and study entry (n = 162).

BMI, body mass index; NS, not significant.

Psychiatric data

As shown in Table 2, the CHRNA7 deletion group exhibited significantly more psychosis (p = 0.032). Additional clinical details of the CHRNA7 deletion probands are outlined in Table 3.

Table 2.

Psychiatric Characteristics of the 217 Probands (Mean ± Standard Deviation, Unless Noted Otherwise)

| Entire sample, n = 217 | CHRNA7 copy neutral, n = 210 | CHRNA7 deletion, n = 7 | Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical diagnoses, n (%) | |||||

| ADHD | 202 (92.6) | 195 (92.4) | 6 (85.7) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Disruptive behavior disorder | 203 (93.1) | 197 (93.4) | 5 (71.4) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| ASD | 42 (19.2) | 40 (18.9) | 1 (14.3) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Depressive disorder | 11 (5) | 9 (4.2) | 1 (14.3) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (0.46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Anxiety disorder | 61 (27.9) | 59 (27.9) | 1 (14.3) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Tic disorder | 41 (18.8) | 39 (18.5) | 1 (14.3) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| Psychotic disorder | 1 (0.46) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | Fisher's exact | 0.0323 |

| Pharmacology, n (%) | |||||

| MPH use | 164 (77.7) | 159 (75.3) | 5 (71.4) | Fisher's exact | NS |

| MPH dose, mg/kg | 1.31 ± 0.71 | 1.31 ± 0.69 | 1.51 ± 1.49 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| Indication for risperidone, n (%)a | |||||

| Aggression/irritability | 185 (86) | 180 (86.5) | 5 (71.4) | Fischer's exact | NS |

| Other | 30 (14) | 28 (13.4) | 2 (28.5) | Fischer's exact | NS |

| Risperidone Tx duration, years | 3.08 ± 2.2 | 3.11 ± 2.23 | 2.28 ± 2.26 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| Risperidone dose, mg/kg | 0.034 ± 0.02 | 0.034 ± 0.02 | 0.046 ± 0.01 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| Risperidone dose, per day (mg/kg) | 1.51 ± 1.09 | 1.49 ± 1.05 | 2.21 ± 1.85 | Welch's t-test (two-tailed) | NS |

| Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 114 (52.3) | 109 (52) | 4 (57.1) | Fisher's exact | NS |

Does not include CHRNA7 duplication.

Data missing for two participants.

Three participants with missing information.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; MPH, methylphenidate-equivalent; NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Additional Clinical Details of CHRNA7 Deletion Probands

| Proband | Family Hx | Suicidal tendencies | Psychosis | Law enforcement involvement | Admitted or institutionalized | Pregnancy complications | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Del01 | Father: ADHD, Tourette's Syndrome, potential for SZ, alcoholism | No | Suspecteda | Yes | No | None | OCD, Nocturnal enuresis, chews hair |

| Del02 | Father: Tourette's syndrome | No | No | No | No | Mother smoked cigarettes during pregnancy | None |

| Del03 | Father: anger problems, Family history of seizure disorder, ADHD, learning problems | No | No | No | Yes | Mother smoked cigarettes during pregnancy, Maternal infection during pregnancy | Math LD, sleep problems, conflicted home environment |

| Del04 | Mother: depression, Father: depression, suicidal tendencies | Yes | Yesa | Yes | Yes | Mother used marijuana during pregnancy | Sleep problems, homicidal tendencies |

| Del05 | Paternal uncle: seizures, SZ, ID | No | No | No | No | Mother smoked cigarettes during pregnancy | Cardiac issues, concern about ASD |

| Del06 | None | Yes | Yesab | No | Yes | None | |

| Del07 | None | No | No | No | No | Mother hospitalized for stress during pregnancy | Nocturnal enuresis |

Hallucinations.

Potential schizophrenia.

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; Del, CHRNA7 deletion; ID, intellectual disability; LD, learning disability; OCD, obsessive compulsive disorder; SZ, schizophrenia.

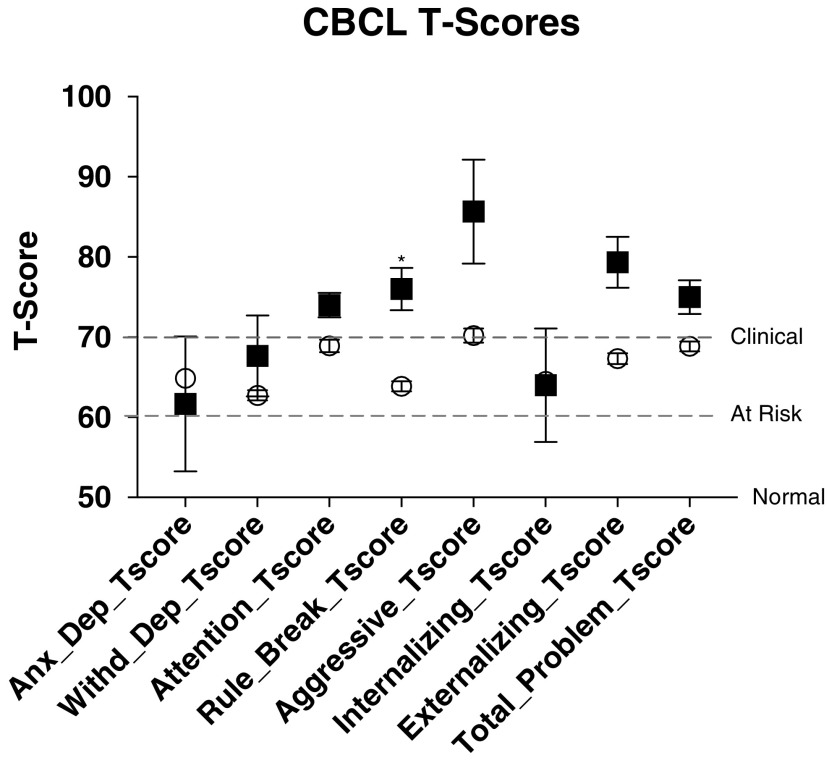

As shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/cap), CHRNA7 deletion probands had significantly higher T-scores for rule breaking, aggression, and externalizing behaviors. All of the probands carrying CHRNA7 deletions were in the “clinical” range, compared with the “at risk” range for those without CHRNA7 deletions. The significant differences remained significant after accounting for age, sex, and weight-adjusted dose of risperidone and psychostimulants (β = 10.1, SE = 4.5, Cohen's d = 1.32, p = 0.0265 for rule breaking, β = 13.7, SE = 6.4, Cohen's d = 1.26, p = 0.0340 for aggression, and β = 10.2, SE = 5.0, Cohen's d = 1.21, p = 0.0422 for externalizing behaviors).

FIG. 2.

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) measurements. T-scores of 50 are “normal,” 60–70 “at risk,” and 70+ “clinical,” as indicated by the dashed lines. CHRNA7 deletion probands (squares) all have significantly increased rule breaking and higher scores for aggression and externalizing behaviors, all in the clinical range. *p < 0.05.

Treatment data

There was no difference between the two groups in several variables related to treatment (Table 2). However, after adjusting for age (p = 0.0146), sex (p = 0.0955), and daily dose of psychostimulants (p = 0.0188), the daily dose of risperidone was 58% higher, although not significantly, for CHRNA7 deletion probands when compared with copy neutral probands (least squares [LS] means: 1.96 mg vs. 1.24 mg, Cohen's d = 0.69, p = 0.0742). This was not the case for the daily dose of psychostimulants (p = 0.5989), after adjusting for age (p < 0.0001), sex (p = 0.4305), and daily dose of risperidone (p = 0.0009).

In one of the studies, participants returned for follow-up 15 months after completing the initial visit. Three CHRNA7 deletion probands returned for a follow-up and all were still taking risperidone. In contrast, among those with copy neutral CHRNA7 who returned (n = 86), 79.1% were still taking risperidone or another antipsychotic (p = 0.5033).

Discussion

We utilized ddPCR to assess the copy number state of CHRNA7 in a cohort of children and adolescents who were treated with risperidone, primarily to target aggression. We hypothesized that CHRNA7 CNVs would be enriched in this population, as there is both murine and human evidence suggesting that the α7 nAChR is implicated in aggressive behavior. We found that 3.2% of our cohort carried CHRNA7 deletions, showing remarkable enrichment in this population as compared with what has been reported in control cohorts (0.02%) (p < 0.0001, Fisher's exact test) (Malhotra and Sebat 2012). The individuals with CHRNA7 deletions had more severe externalizing symptoms compared with the rest of the cohort. Furthermore, individuals with CHRNA7 deletions had a higher prevalence of psychosis than the rest of the cohort, although there may be an underrepresentation of such phenotypes in this cohort due to the limited age range.

Individual chromosomal abnormalities, such as 15q13.3 deletions and duplications, are rare, each accounting for a small portion of neuropsychiatric phenotypes. A number of studies, using CMA databases, have described the range of neurobehavioral traits that result from the CHRNA7 deletions (Hoppman-Chaney et al. 2013; Lowther et al. 2015; Ziats et al. 2016). However, few studies have examined how an individual copy number change contributes to one phenotype.

For CHRNA7 CNVs in particular, enrichment has been found in ADHD (0.6% CHRNA7 duplications) (Williams et al. 2010, 2012), idiopathic generalized epilepsy (1% CHRNA7 deletions and 1% CHRNA7 duplications) (Helbig et al. 2009), and schizophrenia (International Schizophrenia Consortium, 2008). To date, CHRNA7 CNVs have not been found to account for more than 1% of any phenotypic group. For ADHD, CHRNA7 duplications are among the strongest risk factors for the disorder, with an odds ratio of 2.22. In this study, our odds ratio for aggressive behaviors is 183.9 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 69.78–473.4) when considering the prevalence of these deletions among presumably healthy control populations (0.02%) (Malhotra and Sebat 2012), which supports the hypothesis of an extremely high risk for development of aggression with CHRNA7 deletions.

Both children and adolescents with and without CHRNA7 deletions exhibited an elevated level of symptoms, as would be expected in a population treated with antipsychotics. However, probands with CHRNA7 deletions had higher T-scores for the rule breaking and aggression factors of the CBCL, compared with the copy neutral probands (Zahrt and Melzer-Lange 2011). Notwithstanding the fact that pretreatment assessment of symptom severity was not available, this finding is consistent with the contention that CHRNA7 deletions are associated with more significant aggression. This finding is also consistent with the observation that in the one prospective study, where participants returned 1.5 years later, all deletion participants were still receiving risperidone compared with 79% of those without the deletion (Calarge et al. 2015b). Indeed, the deletion probands had anecdotal reports of quite severe aggression, including homicidal threats, serious physical aggression toward others (such as attempting to choke siblings, injuring peers, and biting or assaulting teachers), and involvement with law enforcement. The higher T-scores could also reflect a suboptimal response to treatment, consistent with the observation that the deletion probands received an average dose of risperidone 58% higher than the other group.

Aggression has been noted in probands with 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome previously, but the increased CBCL scores indicate that loss of CHRNA7 may result in being prone toward an aggressive phenotype, possibly of the premeditated instrumental subtype (Nelson and Trainor 2007). Previous work genotyping individuals with intermittent explosive disorder, which consists of reactive–impulsive aggression, supports our findings, given that none was found to carry CHRNA7 deletions (Vu et al. 2011). However, given the variable phenotypic expression of these CNVs, there may be a spectrum of aggressive behaviors.

Psychosis diagnoses were increased in CHRNA7 deletion probands, which was due to one case of schizophrenia in the deletion group but none in the other group. This is consistent with the phenotypes associated with 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome, which includes schizophrenia in 13.6% of probands with the typical 1.5 Mb deletions (Gillentine and Schaaf 2015). Importantly, additional CHRNA7 deletion probands in our study endorsed mild levels of psychotic experiences (e.g., hallucinations), failing to meet diagnostic cutoffs (Table 3). Given their age, our participants have not yet reached the period of highest risk for the onset of psychotic disorders. Thus, the prevalence of schizophrenia in our deletion probands may be underestimated.

With regard to treatment, the CHRNA7 deletion probands had, on average, a 58% higher daily dose of risperidone compared with the non-CHRNA7 deletion probands. As noted earlier, this might reflect a more limited response to risperidone, perhaps related to the pathophysiology underlying their aggression. This would also be consistent with the need to remain on risperidone at follow-up. Several α7 nAChR-targeting drugs have been tested in humans with positive results, although not all have yet been licensed for human use by the Food and Drug Administration (Cubells et al. 2011; Olincy et al. 2016; Gee et al. 2017). Compounds, such as 3-(2,4-dimethoxybenzylidene)anabaseine, an α7 nAChR partial agonist, have been examined in schizophrenia and ASD (Cubells et al. 2011; Olincy et al. 2016). Additionally, type I PAMs, like AVL-3288 (Gee et al. 2017), and type II PAMs, like JNJ39393406, have begun to be tested in small human cohorts.

For 15q13.3 deletions specifically, galantamine has yielded encouraging results in a proband diagnosed with schizophrenia and secondary aggression (Cubells et al. 2011). As such, future effort should aim to investigate the efficacy of α7 nAChR-targeting compounds in patients with aggression and CHRNA7 deletions. Of course, one particular challenge is the potential for receptor desensitization hindering long-term efficacy. However, for the α7 nAChR-targeting compounds that have gone through Phases 1 and 2 clinical trials, it has been noted that the concentration of the drug required for cognitive improvements is very low: lower than those required to activate the α7 nAChR alone and lower than the amount that would desensitize the receptors (Bertrand et al. 2015). Of note, with the development of PAMs for clinical use, this will likely be less of an issue, as these alter the kinetics of the channels differently than agonists.

In large clinical trials, it has also been observed that there is mixed efficacy for some tested α7 nAChR-targeting compounds for certain primary outcomes, including cognition, in schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. However, these are studies based on phenotypes, not genotypes, so it is not surprising that not all individuals respond the same, as there are multiple cellular pathways contributing to the pathology. While there is no perfect compound as of yet, there is active investigation of α7 nAChR-targeting compounds, which may be beneficial for probands with aggressive behaviors carrying 15q13.3 deletions in the future.

Aggression is a multifactorial, complex phenotype. However, in some cases, hereditary factors, such as CHRNA7 deletions, might play a more prominent role in the expression of aggression. Nevertheless, other environmental factors may still exercise an important influence. In fact, several of our probands had been exposed to trauma, including neglect and parental drug use and incarceration. Notably, it has been observed that probands with CHRNA7 deletions are often adopted (Ziats et al. 2016). This highlights the role of gene x environment correlations, and not merely gene x environment interactions, on the clinical phenotype.

Despite being the first to examine the prevalence of CHRNA7 deletions in antipsychotic-treated youth, using high-throughput ddPCR, this study has several limitations. First, while ddPCR allows for rapid CNV testing for a specific region, it does not explore additional CNVs that may be present, or other genetic variation that may be found in an individual. Of note, fewer than 10% of reported individuals with 15q13.3 CNVs have additional CNVs (Gillentine and Schaaf 2015). Of those that do have an additional CNV, only a minority have a secondary CNV of known clinical significance, which typically are not known to be associated with any neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Previous studies have utilized clinical CMA databases, which have enrichment for probands with neurocognitive phenotypes, and obtaining deep clinical data for all these probands is not feasible. Our limited sample size significantly constrained the statistical power of our study. However, unlike larger genetic databases, this cohort was very well characterized clinically.

With a larger sample size, it is also plausible that we would identify additional CHRNA7 duplications, of which we only found one. These are the most common CNVs identified by clinical CMA and have been found to be enriched in both ADHD and epilepsy populations (Gillentine and Schaaf 2015; Gillentine et al. 2017). By taking a phenotype–genotype approach, we can better understand the variations in phenotypes between deletions and duplications of CHRNA7, which could lead to a better understanding of the differing pathophysiology of these reciprocal copy number changes.

In this study, we report a high risk for aggressive behaviors with CHRNA7 deletions, with our odds ratio based on published data of 0.02% healthy controls carrying these losses (Malhotra and Sebat 2012). It is important to note that many of the phenotypes associated with these CNVs, including aggression, may be underdiagnosed in the population. Indeed, it has been found that 10.5% of carriers of CNVs in the normal population actually have undiagnosed ID, and another 33.5% carrying deletions did not graduate high school (Männik et al. 2015). Included in Männik et al.'s (2015) study were individuals carrying 15q13.3 deletions. Thus, it is conceivable that control populations that have not been deeply phenotyped include individuals with borderline clinical behaviors or simply undiagnosed neuropsychiatric disease. It is likely that CHRNA7 deletions could be an even higher risk than we report for developing aggressive behaviors.

Conclusions

In summary, we have identified CHRNA7 deletions in a considerable proportion (3.2%) of a cohort (n = 218) treated with risperidone, predominantly for aggressive behavior. This translates into an odds ratio of 183.9 (95% CI: 69.78–473.4) when considering the rate of these CNVs in control populations. CHRNA7 deletions have been implicated in a wide range of neuropsychiatric disorders, and this study is the first to highlight the aggressive behaviors often observed in affected individuals. Furthermore, we identified clinical differences among individuals treated with risperidone dependent on their CHRNA7 copy number, with those having a heterozygous loss showing increased externalizing problems. Future studies should evaluate the therapeutic potential of α7 nAChR-specific PAMs and/or agonists in this population.

Clinical Significance

CHRNA7 encodes for α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR). In a cohort of probands treated with risperidone primarily for aggression and/or irritability, 3.2% carried CHRNA7 deletions. This implicates nAChR in aggressive behaviors, opening the possibility for individualized pharmacological interventions given that compounds that target this receptor are currently available. This may have beneficial effects among a wide range of psychiatric disorders, where aggression is prevalent. Furthermore, this may have implications for how to address severe aggression in the clinic. While the findings from this study should be replicated in an independent cohort, it may be reasonable to utilize testing for CHRNA7 deletions or genome-wide chromosomal microarray (CMA) analysis in probands with aggression requiring antipsychotics. CMA analysis is currently a first-tier test for patients with intellectual disability/developmental delay, autism spectrum disorder, and multiple congenital abnormalities as per the American College of Human Genetics (ACMG) guidelines, and this group of clinical indications may be expanded as more neuropsychiatric phenotypes have a pathogenomic mechanism identified. As our findings await replication, it would have to be decided by the treating physician in discussion with the affected patient and family whether genetic testing for a clinical indication of aggression should be considered, and how this may be helpful in the respective clinical, emotional, psychological, and potentially therapeutic context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the participants and their families as well as the research team members.

Disclosures

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Ivanova MY, Rescorla LA: Manual for the ASEBA Brief Problem Monitor™ (BPM). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Bahr SM, Tyler BC, Wooldridge N, Butcher BD, Burns TL, Teesch LM, Oltman CL, Azcarate-Peril MA, Kirby JR, Calarge CA: Use of the second-generation antipsychotic, risperidone, and secondary weight gain are associated with an altered gut microbiota in children. Transl Psychiatry 5:e652, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand D, Lee C-HLH, Flood D, Marger F, Donnelly-Roberts D: Therapeutic potential of α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 67:1025–1073, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarge C, Burns T, Schlechte J, Zemel B: Longitudinal examination of the skeletal effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risperidone in boys. J Clin Psychiatry 76:607–613, 2015a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarge C, Nicol G, Schlechte J, Burns T: Cardiometabolic outcomes in children and adolescents following discontinuation of long-term risperidone treatment. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 24:120–129, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarge C, Schlechte J: Bone Mass in Boys with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 47:1749–1755, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarge C, Schlechte J, Burns T, Zemel B: The effect of psychostimulants on skeletal health in boys co-treated with risperidone. J Pediatrics 166:1449.e1–1454.e1, 2015b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubells J, Deoreo E, Harvey P, Garlow S, Garber K, Adam M, Martin C: Pharmaco-genetically guided treatment of recurrent rage outbursts in an adult male with 15q13.3 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 155:805–810, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer C, Aman M: Aggressive behavior in a sample of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spect Dis 5:317–323, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Gee K, Olincy A, Kanner R, Johnson L, Hogenkamp D, Harris J, Tran M, Edmonds S, Sauer W, Yoshimura R, Johnstone T, Freedman R: First in human trial of a type I positive allosteric modulator of alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Pharmacokinetics, safety, and evidence for neurocognitive effect of AVL-3288. J Psychopharmacol 31:434–441, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillentine MA, Berry LN, Goin-Kochel RP, Ali MA, Ge J, Guffey D, Rosenfeld JA, Hannig V, Bader P, Proud M, Shinawi M, Graham BH, Lin A, Lalani SR, Reynolds J, Chen M, Grebe T, Minard CG, Stankiewicz P, Beaudet AL, Schaaf CP: The cognitive and behavioral phenotypes of individuals with CHRNA7 duplications. J Autism Dev Disord 47:549–562, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillentine MA, Schaaf CP: The human clinical phenotypes of altered CHRNA7 copy number. Biochem Pharmacol 97:352–362, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig I, Mefford HC, Sharp AJ, Guipponi M, Fichera M, Franke A, Muhle H, de Kovel C, Baker C, von Spiczak S, Kron KL, Steinich I, Kleefuss-Lie AA, Leu C, Gaus V, Schmitz B, Klein KM, Reif PS, Rosenow F, Weber Y, Lerche H, Zimprich F, Urak L, Fuchs K, Feucht M, Genton P, Thomas P, Visscher F, de Haan G-JJ, Møller RS, Hjalgrim H, Luciano D, Wittig M, Nothnagel M, Elger CE, Nürnberg P, Romano C, Malafosse A, Koeleman BP, Lindhout D, Stephani U, Schreiber S, Eichler EE, Sander T: 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nat Genet 41:160–162, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppman-Chaney N, Wain K, Seger P, Superneau D, Hodge J: Identification of single gene deletions at 15q13.3: Further evidence that CHRNA7 causes the 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome phenotype. Clin Genet 83:345–351, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Schizophrenia Consortium: Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature 455:237–241, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen P, Youngstrom E, Steiner H, Findling R, Meyer R, Malone R, Carlson G, Coccaro E, Aman M, Blair J, Dougherty D, Ferris C, Flynn L, Green E, Hoagwood K, Hutchinson J, Laughren T, Leve L, Novins D, Vitiello B: Consensus report on impulsive aggression as a symptom across diagnostic categories in child psychiatry implications for medication studies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:309–322, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AS, Mineur YS, Smith PH, Cahuzac EL, Picciotto MR: Modulation of aggressive behavior in mice by nicotinic receptor subtypes. Biochem Pharmacol 97:488–497, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowther C, Costain G, Stavropoulos D, Melvin R, Silversides C, Andrade D, So J, Faghfoury H, Lionel A, Marshall C, Scherer S, Bassett A: Delineating the 15q13.3 microdeletion phenotype: A case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Genet Med 17:149–157, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra D, Sebat J: CNVs: Harbingers of a rare variant revolution in psychiatric genetics. Cell 148:1223–1241, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Männik K, Mägi R, Macé A, Cole B, Guyatt AL, Shihab HA, Maillard AM, Alavere H, Kolk A, Reigo A, Mihailov E, Leitsalu L, Ferreira A-MM, Nõukas M, Teumer A, Salvi E, Cusi D, McGue M, Iacono WG, Gaunt TR, Beckmann JS, Jacquemont S, Kutalik Z, Pankratz N, Timpson N, Metspalu A, Reymond A: Copy number variations and cognitive phenotypes in unselected populations. JAMA 313:2044–2054, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Shen Y, Weiss LA, Korn J, Anselm I, Bridgemohan C, Cox GF, Dickinson H, Gentile J, Harris DJ, Hegde V, Hundley R, Khwaja O, Kothare S, Luedke C, Nasir R, Poduri A, Prasad K, Raffalli P, Reinhard A, Smith SE, Sobeih MM, Soul JS, Stoler J, Takeoka M, Tan WH, Thakuria J, Wolff R, Yusupov R, Gusella JF, Daly MJ, Wu BL: Microdeletion/duplication at 15q13.2q13.3 among individuals with features of autism and other neuropsychiatric disorders. J Med Genet 46:242–248, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Trainor B: Neural mechanisms of aggression. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:536–546, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, Grummer-Strawn LM, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics 109:45–60, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olincy A, Blakeley-Smith A, Johnson L, Kem WR, Freedman R: Brief report: Initial trial of alpha7-nicotinic receptor stimulation in two adult patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 46:3812–3817, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Lewis AS, van Schalkwyk GI, Mineur YS: Mood and anxiety regulation by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: A potential pathway to modulate aggression and related behavioral states. Neuropharmacology 96:235–243, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME: NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:28–38, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen JX, Yakel JL: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated calcium signaling in the nervous system. Acta Pharmacol Sin 30:673–680, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinawi M, Schaaf CP, Bhatt SS, Xia Z, Patel A, Cheung SW, Lanpher B, Nagl S, Herding HS, Nevinny-Stickel C, Immken LL, Patel GS, German JR, Beaudet AL, Stankiewicz P: A small recurrent deletion within 15q13.3 is associated with a range of neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Nat Genet 41:1269–1271, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Remsing L: Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:126–141, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bon BW, Mefford HC, Menten B, Koolen DA, Sharp AJ, Nillesen WM, Innis JW, de Ravel TJ, Mercer CL, Fichera M, Stewart H, Connell LE, Ounap K, Lachlan K, Castle B, Van der Aa N, van Ravenswaaij C, Nobrega MA, Serra-Juhé C, Simonic I, de Leeuw N, Pfundt R, Bongers EM, Baker C, Finnemore P, Huang S, Maloney VK, Crolla JA, van Kalmthout M, Elia M, Vandeweyer G, Fryns JP, Janssens S, Foulds N, Reitano S, Smith K, Parkel S, Loeys B, Woods CG, Oostra A, Speleman F, Pereira AC, Kurg A, Willatt L, Knight SJ, Vermeesch JR, Romano C, Barber JC, Mortier G, Pérez-Jurado LA, Kooy F, Brunner HG, Eichler EE, Kleefstra T, de Vries BB: Further delineation of the 15q13 microdeletion and duplication syndromes: A clinical spectrum varying from non-pathogenic to a severe outcome. J Med Genet 46:511–523, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TH, Coccaro EF, Eichler EE, Girirajan S: Genomic architecture of aggression: Rare copy number variants in intermittent explosive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 156B:808–816, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Franke B, Mick E, Anney RJ, Freitag CM, Gill M, Thapar A, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Holmans P, Kent L, Middleton F, Zhang-James Y, Liu L, Meyer J, Nguyen TT, Romanos J, Romanos M, Seitz C, Renner TJ, Walitza S, Warnke A, Palmason H, Buitelaar J, Rommelse N, Vasquez AA, Hawi Z, Langley K, Sergeant J, Steinhausen H-CC, Roeyers H, Biederman J, Zaharieva I, Hakonarson H, Elia J, Lionel AC, Crosbie J, Marshall CR, Schachar R, Scherer SW, Todorov A, Smalley SL, Loo S, Nelson S, Shtir C, Asherson P, Reif A, Lesch K-PP, Faraone SV: Genome-wide analysis of copy number variants in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The role of rare variants and duplications at 15q13.3. Am J Psychiatry 169:195–204, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Zaharieva I, Martin A, Langley K, Mantripragada K, Fossdal R, Stefansson H, Stefansson K, Magnusson P, Gudmundsson OO, Gustafsson O, Holmans P, Owen MJ, O'Donovan M, Thapar A: Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A genome-wide analysis. Lancet 376:1401–1408, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahrt DM, Melzer-Lange MD: Aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev 32:325–332, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziats MN, Goin-Kochel RP, Berry LN, Ali M, Ge J, Guffey D, Rosenfeld JA, Bader P, Gambello MJ, Wolf V, Penney LS, Miller R, Lebel RR, Kane J, Bachman K, Troxell R, Clark G, Minard CG, Stankiewicz P, Beaudet A, Schaaf CP: The complex behavioral phenotype of 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med 18:1111–1118, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.