Abstract

New Findings

-

What is the central question of this study?

Can we experimentally replicate atrial pro‐arrhythmic phenotypes associated with important chronic clinical conditions, including physical inactivity, obesity, diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, compromising mitochondrial function, and clarify their electrophysiological basis?

-

What is the main finding and its importance?

Electrocardiographic and intracellular cardiomyocyte recording at progressively incremented pacing rates demonstrated age‐dependent atrial arrhythmic phenotypes in Langendorff‐perfused murine Pgc1β −/− hearts for the first time. We attributed these to compromised action potential conduction and excitation wavefronts, whilst excluding alterations in recovery properties or temporal electrophysiological instabilities, clarifying these pro‐arrhythmic changes in chronic metabolic disease.

Atrial arrhythmias, most commonly manifesting as atrial fibrillation, represent a major clinical problem. The incidence of atrial fibrillation increases with both age and conditions associated with energetic dysfunction. Atrial arrhythmic phenotypes were compared in young (12–16 week) and aged (>52 week) wild‐type (WT) and peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 beta (Ppargc1b)‐deficient (Pgc1β −/−) Langendorff‐perfused hearts, previously used to model mitochondrial energetic disorder. Electrophysiological explorations were performed using simultaneous whole‐heart ECG and intracellular atrial action potential (AP) recordings. Two stimulation protocols were used: an S1S2 protocol, which imposed extrasystolic stimuli at successively decremented intervals following regular pulse trains; and a regular pacing protocol at successively incremented frequencies. Aged Pgc1β −/− hearts showed greater atrial arrhythmogenicity, presenting as atrial tachycardia and ectopic activity. Maximal rates of AP depolarization (dV/dt max) were reduced in Pgc1β −/− hearts. Action potential latencies were increased by the Pgc1β −/− genotype, with an added interactive effect of age. In contrast, AP durations to 90% recovery (APD90) were shorter in Pgc1β −/− hearts despite similar atrial effective recovery periods amongst the different groups. These findings accompanied paradoxical decreases in the incidence and duration of alternans in the aged and Pgc1β −/− hearts. Limiting slopes of restitution curves of APD90 against diastolic interval were correspondingly reduced interactively by Pgc1β −/− genotype and age. In contrast, reduced AP wavelengths were associated with Pgc1β −/− genotype, both independently and interacting with age, through the basic cycle lengths explored, with the aged Pgc1β −/− hearts showing the shortest wavelengths. These findings thus implicate AP wavelength in possible mechanisms for the atrial arrhythmic changes reported here.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor‐γ coactivator‐1 (PGC‐1), atria, action potential, cardiac arrhythmia

Introduction

Arrhythmogenesis is a complex physiological phenomenon of dysregulated cardiac electrical activity, with both short‐ and long‐term consequences. The complex embryological origins and anatomical structure of the atria make them particularly vulnerable to arrhythmic syndromes. Atrial fibrillation (AF) is of particular clinical importance, affecting 1–3% of individuals in Western countries (Friberg & Bergfeldt, 2013). The processes underpinning its induction and maintenance remain incompletely explained, but involve complex interactions between altered cardiac electrical properties and functional changes in the atria, which occur over the short and long term. It has been suggested that AF is a self‐perpetuating process, triggered initially by focal ectopic activity arising in the pulmonary veins that drive cumulative electrical and structural remodelling processes, themselves generating arrhythmic substrate (Haïssaguerre et al. 1998).

These changes are exacerbated by several interacting upstream factors, with ageing and metabolic disease central to a number of these. There is a pronounced increase in the prevalence of AF with age, from ∼4% of individuals aged 60–70 years to nearly 20% of individuals ≥80 years (Zoni‐Berisso et al. 2014). Likewise, metabolic factors may explain ∼60% of current upward trends in incidences of AF (Miyasaka et al. 2006). Metabolic disease and obesity have been implicated as risk factors, themselves age dependent, for ventricular arrhythmias (Adabag et al. 2015). Likewise, the risk of AF increases with physical inactivity (Mozaffarian et al. 2008), obesity (Tedrow et al. 2010), diabetes mellitus (Nichols et al. 2009) and metabolic syndrome (Watanabe et al. 2008). Amelioration of metabolic disease improves both risk profiles and responses to therapy (Tedrow et al. 2010). Furthermore, it has been shown that manipulation of key components of cellular energy production pathways suppresses arrhythmia in known arrhythmogenic models (Liu et al. 2009).

Mitochondrial function may be integral to relationships between ageing, metabolism and arrhythmia. Mitochondria provide >95% of the ATP required for Ca2+ homeostasis and maintenance of transmembrane ionic gradients in addition to cardiac muscle contraction (Barth & Tomaselli, 2009). Abnormal mitochondrial structure and function have been reported in animal models of AF (Ausma et al. 1997). Analysis of mitochondria from cardiomyocytes of human AF patients demonstrates increased DNA damage (Tsuboi et al. 2001; Lin et al. 2003), structural abnormalities (Bukowska et al. 2008) and impaired function (Lin et al. 2003). Furthermore, a number of targeted mitochondrial DNA mutations accumulate with age and show increased incidences in AF (Lai et al. 2003). Mitochondrial dysfunction also results in generation of reactive oxygen species, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of human AF (Korantzopoulos et al. 2007). Experiments producing acute mitochondrial impairment through ischaemia–reperfusion correspondingly demonstrate pro‐arrhythmic regional heterogeneities in ventricular action potential duration (APD) and arrhythmogenesis suppressed by pharmacological manipulations of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Akar et al. 2005; see also Brown et al. 2010). These pro‐arrhythmic changes were successfully suppressed by pharmacological manipulations of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Akar et al. 2005). Further work demonstrated that stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane potential also inhibits arrhythmias in other settings (Brown et al. 2010).

However, few experiments have explored the effects of chronic age‐dependent energetic deficiency arising from ageing and mitochondrial dysfunction on the generation of atrial arrhythmias or determined their underlying electrophysiological abnormalities. The present study used a peroxisome proliferative activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 beta (Ppargc1b; hereafter Pgc1β)‐deficient (Pgc1β −/−) model (Mouse Genome Informatics identification: MGI:2444934 (http://www.informatics.jax.org/)) that has been used previously to study the biochemical consequences of metabolic energetic deficiency. This family of transcriptional coactivators provides central regulators of cellular and mitochondrial function controlling key metabolic pathways, including fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation. It occurs abundantly in energetically active tissue, such as the heart (Lin et al. 2005). Reduced Pgc1 levels and impaired mitochondrial function occur in diabetes mellitus, the metabolic syndrome, ageing and heart failure (Garnier et al. 2003; Leone & Kelly, 2011). Despite normal baseline function, Pgc1β‐deficient mice demonstrate compromised heart rate responses with adrenergic stimulation (Lelliott et al. 2006). Their ex vivo Langendorff‐perfused hearts show ventricular arrhythmic tendencies, abnormal diastolic Ca2+ transients and altered ion channel expression (Gurung et al. 2011). However, neither their atrial arrhythmic phenotypes nor their accompanying electrophysiological changes have been explored.

The present study complements previous reports in murine hearts carrying genetic abnormalities in specific ion channels modelling ventricular arrhythmic conditions (Huang, 2017). The arrhythmic substrate in these different exemplars was variously identified with altered action potential (AP) initiation and conduction (Martin et al. 2011; Ning et al. 2016), AP recovery (Sabir et al. 2007b) and arrhythmic triggers (Thomas et al. 2007; Goddard et al. 2008). The present experiments, likewise, looked for the presence of arrhythmic phenotypes provoked by the imposition of extrasystolic S2 stimuli at differing S1S2 intervals following trains of regular S1 pacing as well as steady‐state pacing at progressively decreased basic cycle lengths (BCLs). The findings were then matched to results from simultaneous determinations of AP activation and recovery, as well as temporal instabilities in the form of AP alternans (Matthews et al. 2010), APD–diastolic interval (DI) restitution relationships (Kim et al. 2002; Matthews et al. 2012) and spatiotemporal indicators of AP wavelength. This study represents the first to make such measurements in murine atria. Studies in human AF have reported increased slopes in restitution plots of APD–DI, intervening between full AP recovery and the peak of the subsequent AP. However, these studies did not look for accompanying alternans (Kim et al. 2002). However, the present findings do support previous reports associating AF with paradoxical suppression of APD alternans in a vagally mediated canine AF model (Lu et al. 2011).

Methods

Animals and ethical approval

This research was regulated under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012 following ethical review by the University of Cambridge Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (Home Office PPL no. 70/8726), and followed recommendations provided by the Physiological Society (Grundy, 2015). Mice were housed in an animal facility with 12 h–12 h light–dark cycles at a temperature maintained at 21°C. Animals were fed sterile chow (RM3 Maintenance Diet; SDS, Witham, UK) and had free access to water, bedding and environmental stimuli. The C57/B6 mice strain was used as the background for both wild‐type (WT) and Pgc1β −/− mice, generated using a triple LoxP targeting vector as previously described (Lelliott et al. 2006). Four experimental groups were studied: young WT (n = 20), young Pgc1β −/− (n = 23), aged WT (n = 22) and aged Pgc1β −/− (n = 22). All young mice were aged between 12 and 16 weeks and aged mice >52 weeks. Mice were administered 200 IU of unfractionated heparin (Sigma‐Aldrich, Poole, UK) in the intraperitoneal space before being killed by cervical dislocation [Schedule 1; Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986]. No recovery, anaesthetic or surgical procedures were required.

Buffering media

Experimental solutions were based on a Krebs–Henseleit (KH) solution of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 119; NaHCO3, 25; KCl, 4.0; KH2PO4, 1.2; MgCl2, 1.0; CaCl2, 1.8; glucose, 10; and sodium pyruvate, 2.0; pH adjusted to 7.4 and bubbled with 95% O2–5% CO2 (British Oxygen Company, Manchester, UK). Chemical agents were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (Poole, UK) unless otherwise indicated. Before perfusion of isolated Langendorff‐perfused hearts with plain KH solution, perfusion was initiated in the presence of 20 μm blebbistatin (Selleckchem, Newmarket, UK) to reduce movement and allow stable impalements.

Whole‐heart intracellular microelectrode recordings

Animals were killed for rapid sternectomy and cardiectomy. Hearts were cannulated and secured as previously described (Zhang et al. 2011; Matthews et al. 2012; Ning et al. 2016). No obvious macroscopic defects were observed in any heart. Hearts were then mounted on a horizontal Langendorff apparatus that was electrically insulated and incorporated into an intracellular rig within a Faraday cage, incorporating a light microscope (objective ×5, eyepiece ×5; W. Watson and Sons Limited, London, UK), organ bath, custom‐built microelectrode amplifier and head stage.

To facilitate impalement of the left atrium, hearts were mounted in a standard anatomical position to allow pacing from the right atrium (RA) and access to the left atrium (LA). The left atrium was displaced posteriorly and held in place with three A1 insect pins. The positions of the recording and stimulating electrodes were controlled by two precision micromanipulators (Prior Scientific Instruments, Cambridge, UK). In all experiments, the stimulating electrode was consistently positioned at the posterior aspect of the RA, and recordings were made from the central region of the LA, minimizing variability in distances between the respective electrodes, so that alterations in AP latencies therefore provided indications of corresponding conduction velocity changes. Hearts were perfused with plain KH solution (flow rate of 2.05 ml min−1) to allow establishment of a regular intrinsic rhythm. Preparations with an intrinsic rate of <5 Hz or which did not display 1:1 atrioventricular conduction for >10 min postperfusion were not used for experimentation. Perfusion with KH containing 20 μm blebbistatin was then commenced until motion was adequately minimized before resumption of perfusion with plain KH solution.

A microelectrode (tip resistance 15–25 MΩ) was pulled by a custom‐built microelectrode puller from a glass pipette (1.2 mm o.d., 0.69 mm i.d.; Harvard Apparatus, Cambourne, UK), filled with 3 m KCl and then inserted into a right‐angled microelectrode holder (Harvard Apparatus). The recorded signal from the microelectrode was passed through a head stage for preamplification forming part of a high‐input impedance direct‐current microelectrode amplifier system (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK) before bandpass filtering (between 0 and 2 kHz) and analog‐to‐digital conversion at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz (1401; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). A successful impalement was identified by the abrupt appearance of a resting membrane potential more negative than −70 mV and regular APs with a stable waveform. A Ag/AgCl electrode in contact with the bath solution was used as the reference electrode for all measurements.

Whole‐heart ECG recordings

Correlation between electrical signals at the level of the whole organ and intracellular voltage recordings was permitted by simultaneous ECG recordings from the Langendorff‐perfused hearts. Two unipolar ECG electrodes were placed at fixed positions adjacent to the heart in the organ bath that corresponded to the standard three‐lead ECG co‐ordinates. The recorded signals were passed through head stages for preamplification before amplification (Neurolog NL104 amplifier), bandpass filtering (between 5 and 500 Hz; NL 125/6 filter; Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and digitization at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz (1401; Cambridge Electronic Design).

Pacing protocols

Hearts were stimulated at an amplitude of twice diastolic threshold voltage plus 0.5 mV. Hearts underwent two separate pacing protocols during each experiment. First, a standardized S1S2 protocol was used to determine the atrial effective refractory period (AERP) from the ECG recordings. This delivered successive trains of eight S1 stimuli separated by an interval of 125 ms, followed by a solitary extrasystolic stimulus (S2) initially delivered 89 ms after the preceding S1 stimulus. This pattern of stimulation was repeated with the S1S2 interval decremented by 1 ms for each successive cycle until failure of stimulus capture. Incremental pacing protocols then began after achieving stable microelectrode impalement. These consisted of cycles of regular pacing, each of 100 stimulations. They began with a BCL of 130 ms that was then decremented by 5 ms for each subsequent cycle. These were repeated until the heart entered into 2:1 block or sustained arrhythmia.

Data and statistical analysis

Data captured by the Spike2 software package (Cambridge Electronic Design) was analysed using a custom‐written program using the python programming language. Alternans was defined as an occurrence of alternating beat‐to‐beat changes in the value of a parameter such that the direction of the change oscillates for at least 12 successive action potentials. Statistical analysis was carried out using the R programming language (R Core Team, 2015) and plots with the grammar of graphics package (Wickham, 2009). All data are expressed as means ± SD, and a P value of < 0.05 was taken to be significant. Different experimental groups were compared with a two‐factor ANOVA. F values that were significant for interactive effects prompted post hoc testing with Tukey's honest significant difference testing. If single comparisons were made, Student's two‐tailed t test was used to compare significance. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. Kaplan–Meier estimates were compared with the log rank test.

Results

Aged Pgc1β −/− hearts develop a pro‐arrhythmic phenotype

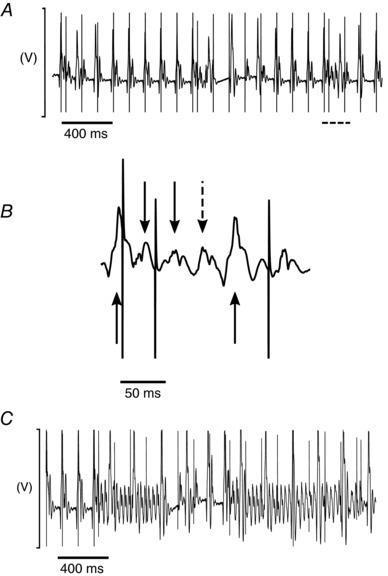

Electrocardiographic recordings were first made through the S1S2 protocol. Extrasystolic (S2) stimuli were interposed at successively shorter intervals following trains of eight regular (S1) stimuli applied at a 125 ms basic cycle length. This explored for the presence and the frequency of arrhythmic phenotypes in the intact ex vivo Langendorff‐perfused hearts. Figure 1 shows typical ECG recordings from aged Pgc1β −/− hearts at a slow time base during an S1S2 stimulation protocol. These include episodes of premature atrial complexes following successive S2 stimuli and a short run of atrial tachycardia captured during a typical stimulus train at the end of an S1S2 protocol (Fig. 1 A). On an expanded time base, these could be characterized by spontaneous atrial P waves (dashed arrow) in contrast to the paced P waves (continuous downward‐pointing arrows) following imposed pacing spikes (Fig. 1 B, arrowed) between successive ventricular complexes (upward‐pointing arrows). Some protocols also elicited runs of atrial tachycardia (Fig. 1 C). The S1S2 interval at the onset of failure of stimulus capture made it possible to determine the AERP corresponding to the specific (8 Hz) pacing rate. A comparison of AERPs obtained from the S1S2 protocol in young WT (24.8 ± 5.8 ms), aged WT (28.8 ± 6.1 ms), young Pgc1β −/− (29.3 ± 3.8 ms) and aged Pgc1β −/− hearts (30.1 ± 8.9 ms) demonstrated no significant differences between groups and provided indications of the extent to which BCLs could be decreased in the succeeding incremental pacing experiments.

Figure 1. Electrocardiographic features of pro‐arrhythmic phenotypes in Pgc‐1β −/− atria.

A, typical ECG recordings from S1S2 protocols, demonstrating premature atrial complexes; dashed section is shown in B, with an expanded time base. Continuous downward‐pointing arrows denote atrial complexes as a result of stimulation. The dashed arrow indicates a premature atrial complex with no preceding stimulation spike. Continuous upward‐pointing arrows denote ventricular complexes. C illustrates atrial tachycardia in response to an S2 stimulus.

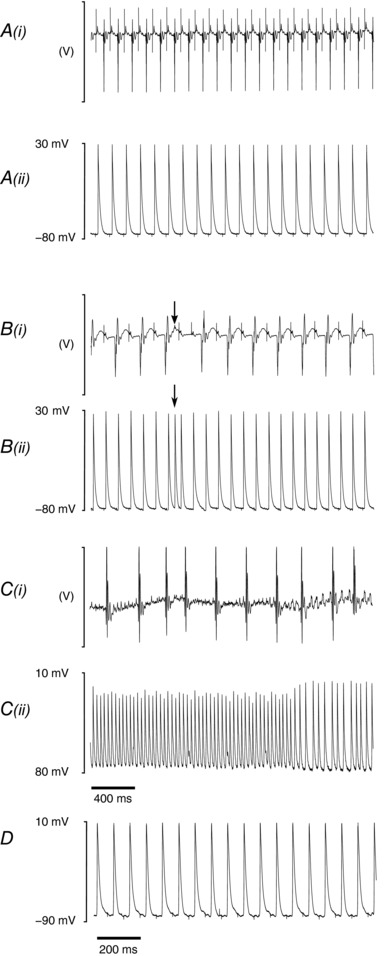

We then performed simultaneous whole‐heart ECG recordings and intracellular AP measurements from single cardiomyocytes after achieving stable microelectrode impalements, with consistent stimulating and recording electrode positions. The intracellular AP recordings provided accurate measurements of AP characteristics related to AP initiation, activation and recovery. These included maximal AP upstroke rates (dV/dt max), AP latencies, defined as the time interval between the pacing spike of each AP and the maximal deflection, or peak, of the AP, AP durations at 90% recovery (APD90), and resting membrane potentials (RMPs). The measurements of dV/dt max and RMPs would not have been available with the monophasic action potential electrode methods used on previous occasions (Sabir et al. 2007a, 2008a). The incremental pacing protocols applied cycles of 100 regular pacing stimuli at successively decremented BCLs. Figure 2 illustrates results of the subsequent incremental pacing procedure comparing ECG (i) and intracellular traces (ii) in conditions of regular activity (Fig. 2 A) and occurrences of premature atrial complexes (Fig. 2 B), atrial fibrillation (Fig. 2 C) and APD90 alternans (Fig. 2 D) in an aged Pgc1β−/− heart. Individual hearts subjected to incremental pacing could therefore display phenotypes that differed from the results of extrasystolic (S2) stimuli.

Figure 2. Electrocardiographic and intracellular recordings during incremental pacing.

A, typical recordings from incremental pacing protocols illustrating steady‐state ECG recordings (i) from a wild‐type (WT) heart as well as the corresponding intracellular action potential (AP) recordings (ii). Ectopic activity (arrow) from an aged Pgc1β −/− heart is shown in B, with the corresponding ECG (i) and intracellular AP recordings (ii). C, evidence of atrial fibrillation in the ECG (i) recording of an aged Pgc1β −/− heart, with concurrent intracellular AP recording (ii). D illustrates AP duration alternans in an AP recording from a young WT heart.

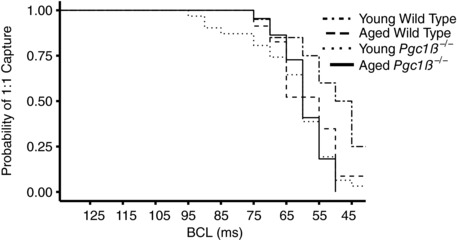

The cycles of incremental pacing continued with decreasing BCLs until the onset of either 2:1 capture or arrhythmia was reached. Kaplan–Meier curves plotting the probability of 1:1 capture of the groups as a function of BCL (Fig. 3) demonstrated a progressive reduction in the number of hearts continuing to show 1:1 capture at BCLs shorter than ∼70 ms. This would reflect their refractory properties at the steady‐state pacing frequencies close to this cut‐off. The statistical analysis to follow will therefore analyse data for parameters at BCLs no shorter than ∼50 ms. A log rank test confirmed that the survival curves were in fact significantly different (P = 0.0028). Young WT hearts showed fall‐offs at shorter BCLs than in the remaining groups and thus could be paced at higher frequencies than the other hearts, including aged WT hearts.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier plot of probability of 1:1 capture as basic cycle length (BCL) is varied for each experimental group.

Table 1 summarizes the incidences of arrhythmic phenomena, whether in the form of atrial tachycardia or ectopic atrial deflections, through both pulse protocols. These together suggested a more marked pro‐arrhythmic phenotype in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts than in the remaining groups. With the S1S2 pulse protocol, the incidence of ectopic deflections was similar between groups, but the incidence of atrial tachycardias was greater in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts than in young WT, aged WT or young Pgc1β −/− hearts, which all showed similar incidences of atrial tachycardias (P = 0.043). Hearts displaying arrhythmias with extrasystolic (S2) provocation often failed to show arrhythmias on incremental pacing, and a relatively small number (three) of hearts showed arrhythmia amongst the experimental groups. The incremental pacing protocol thus resulted in few incidences of atrial tachycardia. Nevertheless, incidences of ectopic deflections were then greater in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts than in young WT, aged WT and young Pgc1β −/− hearts (P = 0.041).

Table 1.

Incidences of atrial arrhythmic events during programmed electrical stimulation and incremental pacing in young and aged wild‐type (WT) and Pgc1β −/− hearts

| S1S2 protocol | Incremental pacing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | Atrial tachycardia | Ectopic events | Atrial tachycardia | Ectopic events |

| Young WT | 3/20 | 8/20 | 0/20 | 2/20 |

| Aged WT | 4/23 | 8/23 | 1/23 | 4/23 |

| Young Pgc1β −/− | 5/23 | 13/23 | 1/23 | 4/23 |

| Aged Pgc1β −/− | 11/22* | 8/22 | 1/22 | 10/22* |

Data are represented as arrhythmic over total number studied. * P < 0.05 on Fisher exact testing.

Altered atrial AP characteristics in young and aged Pgc1β −/− hearts

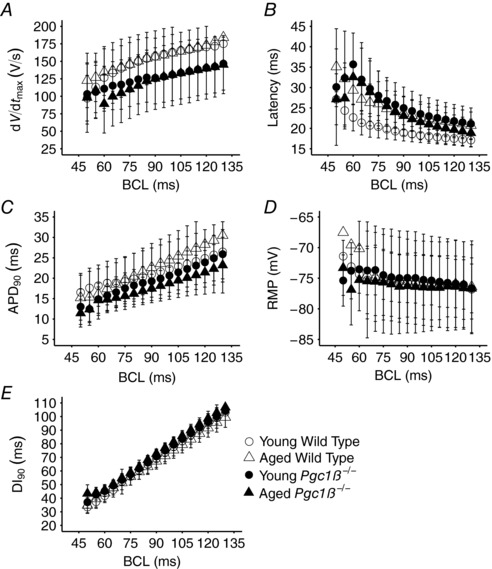

Figure 4 summarizes the activation and recovery characteristics of APs obtained through the incremental pacing procedures. It illustrates the corresponding alterations in dV/dt max (Fig. 4 A), AP latencies (Fig. 4 B), APD90 (Fig. 4 C), RMP (Fig. 4 D) and diastolic intervals intervening between the attainment of 90% of AP recovery and the peak of the subsequent action potential (DI90; Fig. 4 E) with alterations in BCL in young and aged Pgc1β −/− and WT hearts. These parameters varied in a approximately linear manner with BCL, and their overall magnitudes could be compared by the areas beneath their curves. These are summarized in Table 2 which, in addition to showing results from the individual experimental groups of young and aged WT and Pgc1β −/− hearts, also provides the results of grouping all aged, young as well as WT and Pgc1β −/− atria for the statistical analysis. Two‐way ANOVA demonstrated that the Pgc1β −/− hearts displayed decreased dV/dt max (P = 0.000020) and lower APD90 values (P = 0.00018) compared with WT hearts; there were no variations in RMP between groups. Genotype and age exerted significant interacting effects on DI90 and AP latency values (P = 0.0081, P = 0.043, respectively). Post hoc tests did not reveal further statistically significant differences.

Figure 4. Dependence of maximal rate of action potential depolarization (dV/dt max; A), AP latency (B), AP durations to 90% recovery (APD90; C), resting membrane potential (RMP; D) and diastolic interval (DI90; E) on basic cycle length (BCL) in young and aged WT and Pgc1β −/− hearts.

Number of replicates: young WT, n = 20; young Pgc1β −/−, n = 23; aged WT, n = 22; and aged Pgc1β −/−, n = 22.

Table 2.

Areas under the curves of action potential (AP) parameters with respect to basic cycle length

| Parameter | WT | Young WT | Aged WT | Pgc1β −/− | Young Pgc1β −/− | Aged Pgc1β −/− | Young | Aged |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dV/dt max (mV) | 11,765.1 ± 2574.6**** | 12,049.22 ± 2824.5 | 11,518.04 ± 2831.4 | 8979.36 ± 3014.5**** | 8945.29 ± 2891.4 | 9027.37 ± 3225.0 | 10,162.52 ± 3198.7 | 10,300.38 ± 3050.0 |

| APD90 (ms2) | 1702.79 ± 497.9*** | 1703.66 ± 537.3 | 1702.03 ± 474.4 | 1364.53 ± 309.4*** | 1396.49 ± 314.0 | 1319.49 ± 292.9 | 1516.95 ± 423.2 | 1515.01 ± 437.7 |

| DI90 (ms2) | 5292.48 ± 607.2†† | 5486.3 ± 596.2 | 5123.95 ± 578.4 | 5300.77 ± 610.9†† | 5160.93 ± 546.1 | 5497.81 ± 474.8 | 5288.52 ± 645.4†† | 5306.73 ± 557.8†† |

| AP Latency (ms2) | 1721.39 ± 374.3† | 1638.49 ± 318.2 | 1793.47 ± 408.8 | 1831.90 ± 342.3† | 1890.34 ± 376.0 | 1753.00 ± 252.0 | 1779.43 ± 366.2† | 1774.65 ± 347.5† |

| RMP (mV ms) | −5374.71 ± 623.4 | −5492.91 ± 715.0 | −5271.93 ± 530.6 | 5226.35 ± 748.0 | −5075.36 ± 800.2 | −5439.1 ± 563.9 | −5239.11 ± 797.5 | −5353.66 ± 547.0 |

Each symbol represents statistical results from ANOVA. *** P < 0.001 and **** P < 0.0001 for independent effects of genotype. † P < 0.05 and †† P < 0.01 for interacting effects of genotype and age. Number of replicates: young WT, n = 20; young Pgc1β −/−, n = 23; aged WT, n = 22; and aged Pgc1β −/−, n = 22. AP, action potential; dV/dt max, maximum AP upstroke rate; APD90, time to 90% AP recovery; DI90, diastolic interval from 90% AP recovery; RMP, resting membrane potential.

Reduced temporal heterogeneities in atrial AP characteristics in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts

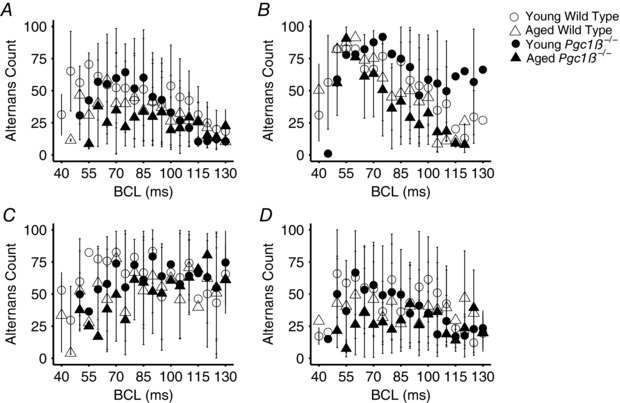

Instabilities in characteristics of successive APs, often taking the form of episodes of alternans, presage major ventricular arrhythmias in clinical situations. They have been described in experimental conditions as alternating variations in temporal properties of AP excitation and/or recovery that occur with varying heart rates in analyses of pro‐arrhythmic tendencies associated with ventricular arrhythmogenesis (Sabir et al. 2007a, 2008a). We sought to analyse whether such phenomena are important in atrial arrhythmogenesis. Figure 5 summarizes the incidences of such alternans in the activation parameters dV/dt max (Fig. 5 A) and AP latency (Fig. 5 B) and the recovery parameters APD90 (Fig. 5 C) and RMP (Fig. 5 D) in young and aged WT and Pgc1β −/− hearts through the incremental pacing protocol. Overall incidences of alternans were assessed by summing the individual incidence of alternans at each BCL. The different groups showed similar distributions in the occurrence of alternans at different BCLs. However, statistical comparisons of the overall incidences of alternans throughout the entire range of BCLs indicated that Pgc1β −/− hearts have reduced incidences and durations of alternans episodes.

Figure 5. Incidence of alternans out of 100 beats at each BCL in the activation variables of maximal rate of AP depolarization, dV/dt max (A) and AP latency (B), and the recovery variables of APD90 (C) and RMP (D) in young WT (open circles), young Pgc1β −/− (filled circles), old WT (open triangles) and Pgc1β −/− hearts (filled triangles).

Number of replicates: young WT, n = 20; young Pgc1β −/−, n = 23; aged WT, n = 22; and aged Pgc1β −/−, n = 22.

Thus, two‐way ANOVA demonstrated that there were no significant effects of genotype on the incidence of alternans in dV/dt max, APD90, AP latency or RMP. Ageing independently reduced the incidence of alternans in aged compared with young hearts (dV/dt max 24 ± 19.9 versus 39 ± 19.7 beats, P = 0.0013; APD90, 37 ± 19.9 versus 50 ± 19.7 beats, P = 0.0051; AP latency, 53 ± 19.9 versus 68 ± 19.7 beats, P = 0.00045; and RMP, 30 ± 13.2 versus 40 ± 13.1 beats; P = 0.0011). Age and genotype exerted interacting effects on the incidence of AP latency alternans (P = 0.032). Post hoc testing demonstrated less AP latency alternans in aged than young Pgc1β −/− hearts (47 ± 23.5 versus 71 ± 14.4 beats, P = 0.00041) and in aged Pgc1β −/− than young WT hearts (47 ± 23.5 versus 64 ± 22.4 beats, P = 0.036).

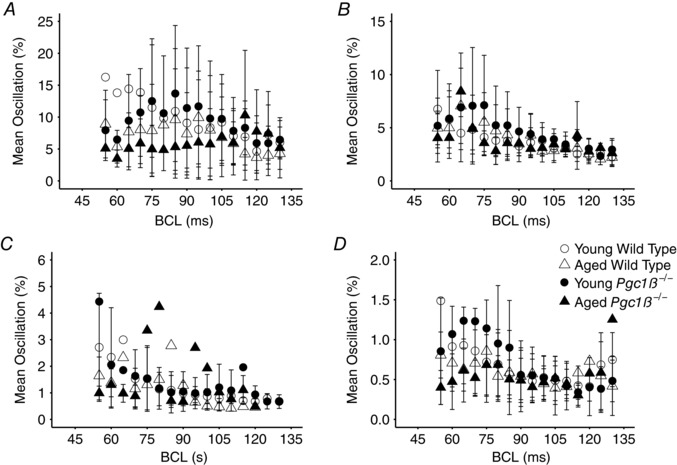

Likewise, two‐way ANOVA demonstrated that the magnitude of dV/dt max, APD90 and RMP (although not AP latency) alternans, reflected in the areas under the respective curves, was smaller in aged than young hearts (P = 0.037, P = 0.038, P = 0.052 and P = 0.066, respectively; Fig. 6). There were no effects of genotype or interacting effects of genotype and age together on the overall magnitudes of oscillation. The total numbers of episodes of APD90, AP latency or RMP alternans were indistinguishable between groups, whilst Pgc1β −/− hearts showed fewer episodes of dV/dt max alternans than WT hearts (8.54 ± 5.0 versus 13.37 ± 9.5 episodes of alternans, P = 0.0021) and aged hearts fewer episodes of dV/dt max alternans than young hearts (9.24 ± 7.5 versus 12 ± 7.5 episodes of alternans, P = 0.030).

Figure 6. Magnitude of alternans as a percentage of the previous beat at each BCL for dV/dt max (A), AP latency (B), APD90 (C) and RMP (D).

Number of replicates: young WT, n = 20; young Pgc1β −/−, n = 23; aged WT, n = 22; and aged Pgc1β −/−, n = 22.

Maximal durations of individual episodes of dV/dt max, AP latency, APD90 or RMP alternans were all shorter in aged than young hearts (dV/dt max, 44 ± 66.3 versus 139 ± 177.0 beats, P = 0.0015; AP latency, 140 ± 126.0 versus 352 ± 183.6, P = 2.7 × 10−8; APD90, 247 ± 325.0 versus 390 ± 393.4 beats, P = 0.049; and RMP, 64 ± 66.3 versus 136 ± 131.1 beats, P = 0.0011). Although they were affected by interacting effects of age and genotype (P = 0.036), post hoc testing demonstrated that these maximal durations were shorter in both aged Pgc1β −/− and aged WT hearts than young Pgc1β −/− hearts (98 ± 79.7 versus 379 ± 167.8 beats, P < 0.00001, and 180 ± 150.0 versus 379 ± 167.8 beats, P = 0.00029, respectively). Furthermore, aged Pgc1β −/− hearts also showed shorter maximal durations of AP latency alternans than young WT hearts (98 ± 79.7 versus 311 ± 210.2 beats, P = 0.00061).

Finally, alternans simultaneously involving different AP characteristics could involve alternating high/low AP latencies or reduced/increased dV/dt max coinciding with or, in the more pro‐arrhythmic pattern, occurring out of phase with higher/lower APD90 values. However, reduced frequencies of simultaneous dV/dt max and APD90 alternans occurred in aged compared with young hearts (14.91 ± 16.1 versus 27.74 ± 19.9%, P = 0.00043) and Pgc1β −/− compared with WT hearts (17.77 ± 2.57 versus 26.59 ± 3.23%, P = 0.024). Reduced and similar proportions of out‐of‐phase alternans occurred in Pgc1β −/− hearts compared with WT hearts (7.83 ± 9.3 versus 19.30 ± 30.0%; P = 0.010) and aged compared with young hearts, respectively (P = 0.070). Likewise, reduced frequencies of simultaneous APD90 and AP latency alternans occurred in aged compared with young hearts (25.67 ± 16.5 versus 45.53 ± 15.9%, P = 0.082 × 10−5), which showed fewer beats of the more pro‐arrhythmic alternans pattern (132 ± 152.6 versus 334 ± 262.3 beats; P = 0.00017).

Spatiotemporal representations of AP excitation in Pgc1β −/− and WT hearts

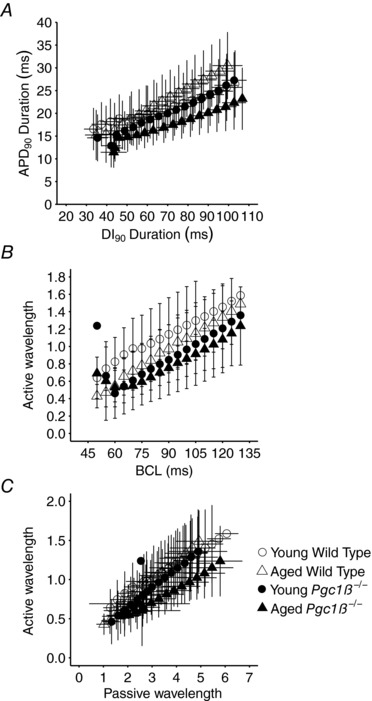

Previous reports in murine ventricles correlated variations in the dependence of AP recovery upon BCL with instabilities in the form of alternans. Restitution curves of APD90 against BCL, or diastolic intervals (DI90) from 90% action potential recovery (Sabir et al. 2008a,b), then associated pro‐arrhythmic instabilities with increasing limiting slopes in APD90 versus DI90 plots with shortening DI90 (Matthews et al. 2012). Attainment of unity gradient presaged waxing AP alternans and arrhythmia. In contrast, results in Fig. 7 A implicated neither genotype (two‐way ANOVA: P = 0.12) nor age (P = 0.15) in independently influencing these limiting slopes. These factors did interact (P = 0.0001), but this gave reduced slopes in aged Pgc1β−/− atria (Tukey's tests: aged Pgc1β −/− versus aged WT, P = 0.001; aged WT versus young WT, P = 0.001), consistent with the observed paradoxically decreased incidences and durations of alternans in aged and Pgc1β −/− hearts and contrasting with their increased arrhythmogenic properties.

Figure 7. Restitution plots of APD90 against DI90 (A) and of active AP wavelength (B) and passive wavelength (C) observed at different BCLs through the incremental pacing procedure in young and old WT and Pgc1β −/− hearts.

Number of replicates: young WT, n = 20; young Pgc1β −/−, n = 23; aged WT, n = 22; and aged Pgc1β −/−, n = 22.

In contrast, analysis of spatial representations of action potential activation, as opposed to the temporal characteristics of AP recovery considered above, replicated the arrhythmic phenotypes in terms of the accompanying electrophysiological abnormalities particularly in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts. Here, the AP travelling waves were represented in terms of wavelengths of excited tissue undergoing APs (λ) and resting wavelengths (λ0) of the succeeding tissues that had completed their subsequent AP recovery. These λ and λ0 terms were obtained by multiplying 1/(AP latency), reflecting conduction velocity, by the corresponding APD90 or DI90 values, respectively (Matthews et al. 2013b). These were then compared in young and aged WT and Pgc1β −/− atria through the different BCLs examined. Areas under plots of λ against BCL (Fig. 7 B) then demonstrated that the Pgc1β −/− as opposed to the WT genotype, but not age, independently (two‐way ANOVA: P = 0.6 × 10−4 and 0.14, respectively) reduced λ. Additional, interacting effects (P = 0.048) through the range of explored BCLs, were reflected in the shorter λ values in both young (Tukey's test: P = 0.0001) and aged Pgc1β −/− (Tukey's test: P = 0.0008) compared with young WT atria. Likewise, λ values from the experimental groups all declined and converged with declining λ0 and with shortening BCL, as previously reported (Matthews et al. 2013a; Ning et al. 2016b; Fig. 7 C). Nevertheless, λ values in aged Pgc1β −/− hearts consistently fell below those in remaining groups (n = 14 points, sign test, P < 0.01). Accordingly, areas beneath the curves reflected significantly greater λ at the longer (85–130 ms; two‐way ANOVA: P = 0.042) but not the shorter (<85 ms) BCLs, resulting from interacting effects of age and Pgc1β −/− genotype (Matthews et al. 2013a; Ning et al. 2016b).

Discussion

Both age and energetic dysfunction are known risk factors for atrial fibrillation (Go et al. 2001; Menezes et al. 2013). The experimental basis for this effect was studied in young and aged Pgc1‐deficient hearts used in previous biochemical studies of mitochondrial dysfunction. Pgc1 upregulates mitochondrial function and cellular energy homeostasis (Lin et al. 2005; Finck & Kelly, 2006), acting on genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and electron transport (Arany et al. 2005). Both ageing WT (Froehlich et al. 1978; Lakatta & Sollott, 2002; Hatch et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2015) and energetically deficient Pgc1β −/− hearts show abnormalities in a range of cellular mechanisms with potential electrophysiological consequences for arrhythmia. Their increased production of reactive oxygen species (Grivennikova et al. 2010) modifies maximal voltage‐dependent Na+ and K+ current (Wang et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2010), sarcolemmal KATP channel function, Na+ and Ca2+ channel inactivation, and late Na+ current and ryanodine receptor function (Huang, 2017). The associated ATP/ADP depletion opens sarcolemmal ATP‐sensitive K+ channels (sarcKATP; Akar & O'Rourke, 2011). Additional abnormalities in Ca2+ homeostasis and delayed after‐depolarization events potentially initiate pro‐arrhythmic triggering activity (Gurung et al. 2011). These mechanisms could in turn potentially alter cell–cell coupling (Smyth et al. 2010), AP conduction (Liu et al. 2010), repolarization and refractoriness (Wang et al. 2004), as well as predispose to alternans and Ca2+‐mediated pro‐arrhythmic triggering phenomena (Terentyev et al. 2008).

Recent studies have reported both compromised heart rate responses to adrenergic stimulation (Lelliott et al. 2006) and pro‐arrhythmic ventricular phenotypes in intact perfused murine Pgc1β −/− hearts (Gurung et al. 2011). However, the corresponding atrial electrophysiological AP or arrhythmic phenotypes have not been investigated. In the present study, we applied cellular electrophysiological recordings in cardiomyocytes within intact, normally functioning Langendorff‐perfused hearts as opposed to isolated cardiomyocytes. We thereby determined steady‐state arrhythmic and related restitution properties of murine atrial tissue for the first time.

Our experimental approach permitted simultaneous study of atrial arrhythmic properties of the whole heart and electrophysiological properties of single atrial cells. Aged Pgc1β −/− hearts demonstrated a significantly greater incidence of arrhythmogenic phenotypes compared with all the remaining groups. The stimulation procedures that applied extrasystolic S2 stimuli resulted in a higher incidence of atrial tachycardias, whereas those applying incremental increases in steady heart rates resulted in a higher incidence of ectopic atrial events. The latter suggests that atrial cardiomyocytes have a greater capacity for rapid pacing without producing pro‐arrhythmic phenomena.

The association of the arrhythmic phenotype with alterations in the corresponding AP characteristics was then examined. Of the measured AP parameters, resting membrane potentials remained uniform throughout all experimental groups, consistent with clinical findings in atrial fibrillation (Bosch et al. 1999). The statistically most noticeable alterations involved compromised AP activation, which has been implicated in arrhythmic substrate on previous occasions (Huang et al. 2012; King et al. 2013a; Huang, 2017). Thus, Pgc1β −/− atria displayed decreased dV/dt max compared with WT atria, in the absence of statistical effects of age or interactions between age and genotype. The dV/dt max correlates with peak Na+ current, which in turn markedly influences AP conduction velocity to an extent dependent upon the conductivity between cells (Hunter et al. 1975; Hondeghem & Katzung, 1977; Usher‐Smith et al. 2006; Fraser et al. 2011). Although young and aged Pgc1β −/− atria did not demonstrate significant differences in dV/dt max, AP latency measurements reflecting conduction velocity were influenced by interactions between age and genotype. They therefore account for the more marked pro‐arrhythmic phenotype in the aged than the young Pgc1β −/− atria.

These findings are compatible with hypotheses relating reduced dV/dt max and increased AP latency to decreased peak Na+ current in the conditions of age‐dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in Pgc1β −/− hearts (Hondeghem & Katzung, 1977; Usher‐Smith et al. 2006; Fraser et al. 2011). Established reports associate metabolic insufficiency with reduced Na+ channel function in a number of circumstances. First, in addition to reduced provision of ATP, disrupted mitochondrial activity increases production of reactive oxygen species (Manning et al. 1984; Fosset et al. 1988; Faivre & Findlay, 1990) and perturbs cytosolic NAD+/NADH. Both factors are implicated in altered Na+ channel function in metabolically stressed cardiomyocytes (Liu et al. 2009) and are rescued by the mitochondrial reactive oxygen species scavenger mitoTEMPO (Liu et al. 2010).

Second, Pgc1β −/− cardiomyocytes show altered Ca2+ homeostasis manifest in abnormal diastolic Ca2+ transients (Gurung et al. 2011). Other murine models show an altered Ca2+ homeostasis implicated in slowed AP conduction accompanying reduced dV/dt max (Zhang et al. 2013). These were attributed to compromised Na+ currents resulting from (i) reduced NaV1.5 expression (Ning et al. 2016) and/or (ii) acute effects upon NaV1.5 function (King et al. 2013b,c). These observations were reported in RyR2‐P2328S/P2328S cardiomyocytes, which likewise show abnormal Ca2+‐handling phenotypes (Gurung et al. 2011). They also follow acute manipulations in Ca2+ homeostasis by caffeine or Epac‐mediated RyR2 agonism or cyclopiazonic acid‐mediated Ca2+‐ATPase antagonism (King et al. 2013b; Li et al. 2017). Patch‐clamped WT cardiomyocytes likewise show acutely reduced or increased Na+ current and dV/dt max, with respective increases in, or sequestration of, the pipette [Ca2+] (Casini et al. 2009).

Comparison of the present findings of reduced dV/dt max and increased AP latency in cardiomyocytes in intact tissue with the normal or even enhanced Na+ currents in Pgc1β −/− cardiomyocytes subject to patch‐clamping involving Ca2+ chelation by intrapipette BAPTA (Gurung et al. 2011) are compatible with a mechanism of action involving the latter, acute effects, of altered Ca2+ homeostasis upon membrane excitability. This could involve Ca2+–Nav1.5 interactions involving direct Ca2+–NaV1.5 binding at an EF hand motif close to the NaV1.5 C‐terminal (Wingo et al. 2004) or indirect Ca2+ binding involving additional ‘IQ’ domain binding sites for Ca2+–calmodulin in the NaV1.5 C‐terminal region (Mori et al. 2000; Wagner et al. 2011; Grandi & Herren, 2014). If so, these findings in a model for metabolic disturbance provide a further example of potentially important effects of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis on arrhythmic substrate through altering AP propagation as a result of acute effects upon Na+ channel function.

The electrophysiological alterations of atrial cardiomyocytes presented in this study led to investigations to distinguish mechanisms for the resulting arrhythmic substrate at the tissue level (Martin et al. 2012), relating these to previous reports from monogenic murine arrhythmic models. First, arrhythmic syndromes primarily attributed to repolarization abnormalities have been exemplified by murine Scn5a+/∆KPQ hearts. Arrhythmic substrate was there associated with altered relationships between APD90 and effective refractory period with varying diastolic interval (DI90; Nolasco & Dahlen, 1968; Sabir et al. 2008a; Matthews et al. 2010, 2012) increasing the steepness of restitution curve plots of APD90 against DI90 at short BCLs. The consequent APD90 instabilities would increase frequencies and amplitudes of alternans, culminating in arrhythmic substrate (Huang, 2017).

However, the present findings did not implicate such alternans in the arrhythmic instability in aged Pgc1β −/− atria. Atrial alternans was observed in AP trains during incremental steady‐state pacing. However, its incidence was not increased by age or Pgc1β −/− genotype. Indeed, aged atria showed decreased incidences of alternans compared with young hearts. The Pgc1β −/− and aged atria showed fewer episodes of alternans than WT and young atria, respectively. Furthermore, it was the restitution curves of aged Pgc1β −/− hearts that showed the most reduced limiting slopes. These findings parallel previous reports in the vagally induced model of canine AF that likewise showed paradoxically less alternans and a flatter restitution slope than in the non‐arrhythmic control state (Lu et al. 2011). Atrial Pgc1β −/− cardiomyocytes thus showed greater capacity to follow rapid pacing without producing pro‐arrhythmic alternans phenomena. This would be compatible with their shorter APDs reflecting more rapid AP recoveries, despite their more prolonged activation processes.

Second, other arrhythmic syndromes have been contrastingly attributed to altered AP conduction, exemplified by murine Scn5a +/− hearts (Martin et al. 2012). This modifies the spatial extent and homogeneity of the travelling waves of AP excitation, or the quiescence that follows it. These were quantified by active wavelengths (λ) derived from conduction velocity [reflected by 1/(AP latency)] and APD terms (given by APD90; Matthews et al. 2013), and resting wavelengths (λ0) comprising DI90 and AP latency terms (Matthews et al. 2013; Ning et al. 2016). Larger λ values reduce likelihoods that areas of depolarization and repolarization coincide at tissue heterogeneities, increasing the safety factor that ensures continued undisrupted propagation of the travelling wave (Weiss et al. 2005). Conversely, decreased λ values increase such likelihoods and those of the consequent wave break‐ups into multiple wavelets, scroll‐waves (Davidenko et al. 1995; Zaitsev et al. 2000; Pandit & Jalife, 2013) and further wavebreaks disrupting the AP conduction pathways (Spector, 2013). Clinical observations correspondingly associate short AP wavelengths with AF inducibility and maintenance (Hwang et al. 2015), particularly in AF patients (Padeletti et al. 1995).

The present analysis indeed demonstrated that in plots of λ against either BCL or λ0, Pgc1β −/− and, particularly, aged Pgc1β −/− atria consistently gave shorter λ in direct parallel with their pro‐arrhythmic phenotype. Altered AP conduction with its consequences for its spatiotemporal properties thus constitutes a potential mechanism for the atrial arrhythmic changes associated with age and energetic compromise reported here.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

C.L.‐H.H., H.V. and S.A. were involved in conception and design of the work, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. J.A.F. was involved in conception and design and drafting the work. K.J. was involved in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

We thank the Wellcome Trust (105727/Z/14/Z), Medical Research Council (MR/M001288/1), British Heart Foundation (PG/14/79/31102 and PG/15/12/31280), Isaac Newton Trust–Wellcome Trust ISSF–University of Cambridge Joint Research Grants Scheme, Sudden Arrhythmic Death Syndrome (SADS) UK society, and the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/2014/SKK01/PERDANA/02/1; Ministry of Education, Malaysia) for their generous support.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paul Frost and Vicky Johnson for their technical assistance.

Edited by: Ming Lei

References

- Adabag S, Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Chen LY, Sotoodehnia N, Siscovick D, Deo R, Konety S, Alonso A & Folsom AR (2015). Obesity related risk of sudden cardiac death in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Heart 101, 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar FG, Aon MA, Tomaselli GF, O'Rourke B & Tomaselli G (2005). The mitochondrial origin of postischemic arrhythmias. J Clin Invest 115, 3527–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar FG & O'Rourke B (2011). Mitochondria are sources of metabolic sink and arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther 131, 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z, He H, Lin J, Hoyer K, Handschin C, Toka O, Ahmad F, Matsui T, Chin S, Wu PH, Rybkin II, Shelton JM, Manieri M, Cinti S, Schoen FJ, Bassel‐Duby R, Rosenzweig A, Ingwall JS & Spiegelman BM (2005). Transcriptional coactivator PGC‐1α controls the energy state and contractile function of cardiac muscle. Cell Metab 1, 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausma J, Wijffels M, Thoné F, Wouters L, Allessie M & Borgers M (1997). Structural changes of atrial myocardium due to sustained atrial fibrillation in the goat. Circulation 96, 3157–3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AS & Tomaselli GF (2009). Cardiac metabolism and arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2, 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch RF, Zeng X, Grammer JB, Popovic K, Mewis C & Kuhlka V (1999). Ionic mechanisms of electrical remodeling in human atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 44, 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Aon MA, Frasier CR, Sloan RC, Maloney AH, Anderson EJ & O'Rourke B (2010). Cardiac arrhythmias induced by glutathione oxidation can be inhibited by preventing mitochondrial depolarization. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48, 673–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowska A, Schild L, Keilhoff G, Hirte D, Neumann M, Gardemann A, Neumann KH, Röhl FW, Huth C, Goette A & Lendeckel U (2008). Mitochondrial dysfunction and redox signaling in atrial tachyarrhythmia. Exp Biol Med 233, 558–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casini S, Verkerk AO, van Borren MMGJ, van Ginneken ACG, Veldkamp MW, de Bakker JMT & Tan HL (2009). Intracellular calcium modulation of voltage‐gated sodium channels in ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 81, 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidenko JM, Salomonsz R, Pertsov AM, Baxter WT & Jalife J (1995). Effects of pacing on stationary reentrant activity. Theoretical and experimental study. Circ Res 77, 1166–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre JF & Findlay I (1990). Action potential duration and activation of ATP‐sensitive potassium current in isolated guinea‐pig ventricular myocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1029, 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finck BN & Kelly DP (2006). PGC‐1 coactivators: inducible regulators of energy metabolism in health and disease. J Clin Invest 116, 615–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosset M, De Weille JR, Green RD, Schmid‐Antomarchi H & Lazdunski M (1988). Antidiabetic sulfonylureas control action potential properties in heart cells via high affinity receptors that are linked to ATP‐dependent K+ channels. J Biol Chem 263, 7933–7936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JA, Huang CLH & Pedersen TH (2011). Relationships between resting conductances, excitability, and t‐system ionic homeostasis in skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol 138, 95–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg L & Bergfeldt L (2013). Atrial fibrillation prevalence revisited. J Intern Med 274, 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich JP, Lakatta EG, Beard E, Spurgeon HA, Weisfeldt ML & Gerstenblith G (1978). Studies of sarcoplasmic reticulum function and contraction duration in young adult and aged rat myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 10, 427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier A, Fortin D, Deloménie C, Momken I, Veksler V & Ventura‐Clapier R (2003). Depressed mitochondrial transcription factors and oxidative capacity in rat failing cardiac and skeletal muscles. J Physiol 551, 491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV & Singer DE (2001). Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 285, 2370–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard CA, Ghais NS, Zhang Y, Williams AJ, Colledge WH, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2008). Physiological consequences of the P2328S mutation in the ryanodine receptor (RyR2) gene in genetically modified murine hearts. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 194, 123–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi E, Herren AW (2014). CaMKII‐dependent regulation of cardiac Na+ homeostasis. Front Pharmacol 5, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikova VG, Kareyeva AV & Vinogradov AD (2010). What are the sources of hydrogen peroxide production by heart mitochondria? Biochim Biophys Acta 1797, 939–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy D (2015). Principles and standards for reporting animal experiments in The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology . J Physiol 593, 2547–2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung IS, Medina‐Gomez G, Kis A, Baker M, Velagapudi V, Neogi SG, Campbell M, Rodriguez‐Cuenca S, Lelliott C, McFarlane I, Oresic M, Grace AA, Vidal‐Puig A & Huang CLH (2011). Deletion of the metabolic transcriptional coactivator PGC1β induces cardiac arrhythmia. Cardiovasc Res 92, 29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P & Clementi J (1998). Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med 339, 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch F, Lancaster MK & Jones SA (2011). Aging is a primary risk factor for cardiac arrhythmias: disruption of intracellular Ca2+ regulation as a key suspect. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 9, 1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM & Katzung BG (1977). Time‐ and voltage‐dependent interactions of antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta 472, 373–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CLH (2017). Murine electrophysiological models of cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev 97, 283–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL‐H, Lei L, Matthews GDK, Zhang Y & Lei M (2012). Pathophysiological mechanisms of sino‐atrial dysfunction and ventricular conduction disease associated with SCN5A deficiency: insights from mouse models. Front Physiol 3, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter PJ, McNaughton PA & Noble D (1975). Analytical models of propagation in excitable cells. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 30, 99–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang M, Park J, Lee YS, Park JH, Choi SH, Shim EB & Pak HN (2015). Fibrillation number based on wavelength and critical mass in patients who underwent radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 62, 673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Kim YH, Hwang GS, Pak HN, Lee SC, Shim WJ, Oh DJ & Ro YM (2002). Action potential duration restitution kinetics in human atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 39, 1329–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Huang CLH & Fraser JA (2013a). Determinants of myocardial conduction velocity: implications for arrhythmogenesis. Front Physiol 4, 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Wickramarachchi C, Kua K, Du Y, Jeevaratnam K, Matthews HR, Grace AA, Huang CLH & Fraser JA (2013b). Loss of Nav1.5 expression and function in murine atria containing the RyR2‐P2328S gain‐of‐function mutation. Cardiovasc Res 99, 751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J, Zhang Y, Lei M, Grace A, Huang CLH & Fraser J (2013c). Atrial arrhythmia, triggering events and conduction abnormalities in isolated murine RyR2‐P2328S hearts. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 207, 308–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis TM, Galaris D & Goudevenos JA (2007). The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 115, 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai LP, Tsai CC, Su MJ, Lin JL, Chen YS, Tseng YZ & Huang SKS (2003). Atrial fibrillation is associated with accumulation of aging‐related common type mitochondrial DNA deletion mutation in human atrial tissue. Chest 123, 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG & Sollott SJ (2002). Perspectives on mammalian cardiovascular aging: humans to molecules. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 132, 699–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelliott CJ, Medina‐Gomez G, Petrovic N, Kis A, Feldmann HM, Bjursell M, Parker N, Curtis K, Campbell M, Hu P, Zhang D, Litwin SE, Zaha VG, Fountain KT, Boudina S, Jimenez‐Linan M, Blount M, Lopez M, Meirhaeghe A, Bohlooly‐Y M, Storlien L, Strömstedt M, Snaith M, Oresic M, Abel ED, Cannon B & Vidal‐Puig A (2006). Ablation of PGC‐1β results in defective mitochondrial activity, thermogenesis, hepatic function, and cardiac performance. PLoS Biol 4, e369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone TC & Kelly DP (2011). Transcriptional control of cardiac fuel metabolism and mitochondrial function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 76, 175–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hothi S, Salvage S, Jeevaratnam K, Grace A & Huang C, 2017. Arrhythmic effects of Epac‐mediated ryanodine receptor activation in Langendorff‐perfused murine hearts are associated with reduced conduction velocity. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 44, 686–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Handschin C & Spiegelman BM (2005). Metabolic control through the PGC‐1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab 1, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PH, Lee SH, Su CP & Wei YH (2003). Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA in atrial muscle of patients with atrial fibrillation. Free Radic Biol Med 35, 1310–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Liu H & Dudley SC (2010). Reactive oxygen species originating from mitochondria regulate the cardiac sodium channel. Circ Res 107, 967–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Sanyal S, Gao G, Gurung IS, Zhu X, Gaconnet G, Kerchner LJ, Shang LL, Huang CLH, Grace A, London B & Dudley SC (2009). Cardiac Na+ current regulation by pyridine nucleotides. Circ Res 105, 737–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Cui B, He B, Hu X, Wu W, Wu L, Huang C, Po SS & Jiang H (2011). Distinct restitution properties in vagally mediated atrial fibrillation and six‐hour rapid pacing‐induced atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res 89, 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AS, Coltart DJ & Hearse DJ (1984). Ischemia and reperfusion‐induced arrhythmias in the rat. Effects of xanthine oxidase inhibition with allopurinol. Circ Res 55, 545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Guzadhur L, Grace AA, Lei M & Huang CLH (2011). Mapping of reentrant spontaneous polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in a Scn5a+/− mouse model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300, H1853–H1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CA, Matthews GDK & Huang CLH (2012). Sudden cardiac death and inherited channelopathy: the basic electrophysiology of the myocyte and myocardium in ion channel disease. Heart 98, 536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews GDK, Guzadhur L, Grace A & Huang CLH (2012). Nonlinearity between action potential alternans and restitution, which both predict ventricular arrhythmic properties in Scn5a +/− and wild‐type murine hearts. J Appl Physiol 112, 1847–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews GDK, Guzadhur L, Sabir IV, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2013). Action potential wavelength restitution predicts alternans and arrhythmia in murine Scn5a +/− hearts. J Physiol 591, 4167–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews GDK, Martin CA, Grace AA, Zhang Y & Huang CLH (2010). Regional variations in action potential alternans in isolated murine Scn5a +/− hearts during dynamic pacing. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 200, 129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes AR, Lavie CJ, Dinicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe J, Morin DP, Khatib S, Abi‐Samra FM, Messerli FH & Milani RV (2013). Cardiometabolic risk factors and atrial fibrillation. Rev Cardiovasc Med 14, e73–e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB & Tsang TSM (2006). Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation 114, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Konno T, Ozawa T, Murata M, Imoto K & Nagayama K (2000). Novel interaction of the voltage‐dependent sodium channel (VDSC) with calmodulin: does VDSC acquire calmodulin‐mediated Ca2+‐sensitivity? Biochemistry 39, 1316–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Furberg CD, Psaty BM & Siscovick D (2008). Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Circulation 118, 800–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols GA, Reinier K & Chugh SS (2009). Independent contribution of diabetes to increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation. Diabetes Care 32, 1851–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning F, Luo L, Ahmad S, Valli H, Jeevaratnam K, Wang T, Guzadhur L, Yang D, Fraser JA, Huang CLH, Ma A & Salvage SC (2016). The RyR2‐P2328S mutation downregulates Nav1.5 producing arrhythmic substrate in murine ventricles. Pflugers Arch 468, 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolasco JB & Dahlen RW (1968). A graphic method for the study of alternation in cardiac action potentials. J Appl Physiol 25, 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padeletti L, Michelucci A, Giovannini T, Porciani M, Bamoshmoosh M, Mezzani A, Chelucci A, Pieragnoli P & Gensini G (1995). Wavelength index at three atrial sites in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 18, 1266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit SV & Jalife J (2013). Rotors and the dynamics of cardiac fibrillation. Circ Res 112, 849–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. ISBN: 3‐900051‐07‐0. Available online at http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Sabir IN, Fraser JA, Cass TR, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2007a). A quantitative analysis of the effect of cycle length on arrhythmogenicity in hypokalaemic Langendorff‐perfused murine hearts. Pflugers Arch 454, 925–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir IN, Fraser JA, Killeen MJ, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2007b). The contribution of refractoriness to arrhythmic substrate in hypokalemic Langendorff‐perfused murine hearts. Pflugers Arch 454, 209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir IN, Li LM, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2008a). Restitution analysis of alternans and its relationship to arrhythmogenicity in hypokalaemic Langendorff‐perfused murine hearts. Pflugers Arch 455, 653–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir IN, Li LM, Jones VJ, Goddard CA, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2008b). Criteria for arrhythmogenicity in genetically‐modified Langendorff‐perfused murine hearts modelling the congenital long QT syndrome type 3 and the Brugada syndrome. Pflugers Arch 455, 637–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JW, Hong TT, Gao D, Vogan JM, Jensen BC, Fong TS, Simpson PC, Stainier DYR, Chi NC & Shaw RM (2010). Limited forward trafficking of connexin 43 reduces cell‐cell coupling in stressed human and mouse myocardium. J Clin Invest 120, 266–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector P (2013). Principles of cardiac electric propagation and their implications for re‐entrant arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 6, 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedrow UB, Conen D, Ridker PM, Cook NR, Koplan BA, Manson JE, Buring JE & Albert CM (2010). The long‐ and short‐term impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (women's health study). J Am Coll Cardiol 55, 2319–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terentyev D, Gyorke I, Belevych AE, Terentyeva R, Sridhar A, Nishijima Y, de Blanco EC, Khanna S, Sen CK, Cardounel AJ, Carnes CA & Györke S (2008). Redox modification of ryanodine receptors contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in chronic heart failure. Circ Res 103, 1466–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G, Gurung IS, Killeen MJ, Hakim P, Goddard CA, Mahaut‐Smith MP, Colledge WH, Grace AA & Huang CLH (2007). Effects of L‐type Ca2+ channel antagonism on ventricular arrhythmogenesis in murine hearts containing a modification in the Scn5a gene modelling human long QT syndrome 3. J Physiol 578, 85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi M, Hisatome I, Morisaki T, Tanaka M, Tomikura Y, Takeda S, Shimoyama M, Ohtahara A, Ogino K, Igawa O, Shigemasa C, Ohgi S & Nanba E (2001). Mitochondrial DNA deletion associated with the reduction of adenine nucleotides in human atrium and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Clin Invest 31, 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usher‐Smith JA, Xu W, Fraser JA & Huang CLH (2006). Alterations in calcium homeostasis reduce membrane excitability in amphibian skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch 453, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Ruff HM, Weber SL, Bellmann S, Sowa T, Schulte T, Anderson ME, Grandi E, Bers DM, Backs J, Belardinelli L & Maier LS (2011). Reactive oxygen species‐activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIδ is required for late I Na augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ Res 108, 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang H, Zhang Y, Gao H, Nattel S & Wang Z (2004). Impairment of HERG K+ channel function by tumor necrosis factor‐α: role of reactive oxygen species as a mediator. J BiolChem 279, 13289–13292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Tanabe N, Watanabe T, Darbar D, Roden DM, Sasaki S & Aizawa Y (2008). Metabolic syndrome and risk of development of atrial fibrillation: the Niigata preventive medicine study. Circulation 117, 1255–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JN, Qu Z, Chen PS, Lin SF, Karagueuzian HS, Hayashi H, Garfinkel A & Karma A (2005). The dynamics of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation 112, 1232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H (2009). ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer‐Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wingo TL, Shah VN, Anderson ME, Lybrand TP, Chazin WJ & Balser JR (2004). An EF‐hand in the sodium channel couples intracellular calcium to cardiac excitability. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Yang Z, Wu C, Li W & Xu H (2015). [Electrophysiological properties and mechanism of aging for the susceptibility of left atrium to arrhythmogenesis in rabbits]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 95, 2302–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev AV, Berenfeld O, Mironov SF, Jalife J & Pertsov AM (2000). Distribution of excitation frequencies on the epicardial and endocardial surfaces of fibrillating ventricular wall of the sheep heart. Circ Res 86, 408–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Fraser JA, Jeevaratnam K, Hao X, Hothi SS, Grace AA, Lei M & Huang CL‐H (2011). Acute atrial arrhythmogenicity and altered Ca2+ homeostasis in murine RyR2‐P2328S hearts. Cardiovasc Res 89, 794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wu J, Jeevaratnam K, King JH, Guzadhur L, Ren X, Grace AA, Lei M, Huang CLH & Fraser JA (2013). Conduction slowing contributes to spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in intrinsically active murine RyR2‐P2328S hearts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 24, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoni‐Berisso M, Lercari F, Carazza T & Domenicucci S (2014). Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: European perspective. Clin Epidemiol 6, 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]