Abstract

Aims

1) To describe open source legal datasets, created for research use, that capture the key provisions of U.S. state medical marijuana laws. The data document how state lawmakers have regulated a medicine that remains, under federal law, a Schedule I illegal drug with no legitimate medical use. 2) To demonstrate the variability that exists across states in rules governing patient access, product safety, and dispensary practice.

Methods

Two legal researchers collected and coded state laws governing marijuana patients, product safety, and dispensaries in effect on February 1, 2017, creating three empirical legal datasets. We used summary tables to identify the variation in specific statutory provisions specified in each state’s medical marijuana law as it existed on February 1, 2017. We compared aspects of these laws to the traditional Federal approach to regulating medicine. Full datasets, codebooks and protocols are available through the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (http://www.pdaps.org/; http://www.webcitation.org/6qv5CZNaZ).

Results

Twenty-eight states (including the District of Columbia) have authorized medical marijuana. Twenty-seven specify qualifying diseases, which differ across states. All states protect patient privacy; only 14 protect patients against discrimination. Eighteen states have mandatory product safety testing before any sale. While the majority have package/label regulations, states have a wide range of specific requirements. Most regulate dispensaries, with considerable variation in specific provisions such as permitted product supply sources, number of dispensaries per state and restricting proximity to various types of location.

Conclusions

The federal ban in the USA on marijuana has resulted in a patchwork of regulatory strategies that are not uniformly consistent with the approach usually taken by the Federal government and whose effectiveness remains unknown.

Keywords: Medical Cannabis, Marijuana Law, regulation, legal epidemiology

Introduction

As of February 1, 2017, twenty years after California(1) became the first U.S. state authorizing medical marijuana (MM), 27 states and the District of Columbia have MM laws, enacted through ballot initiatives or legislation, or both. Many of these laws have evolved in response to local experience and the federal government’s changing and often uncertain policy on MM.(2) While the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970 continues to classify marijuana as a Schedule I drug with no acceptable medical use and high potential for abuse,(3, 4) the Obama administration adopted a position of non-interference,(5) and Congress has prohibited the Department of Justice from interfering with states implementing medical marijuana laws.(6, 7) It is uncertain whether the Trump Administration will maintain this non-interference policy. Regardless, federal law has important effects beyond the risks of prosecution.

MM proponents contend that federal MM prohibition reduces clinicians’ treatment options and patients’ access to MM, hinders research efforts to rigorously evaluate MM, runs counter to high levels of clinician and public support for legalizing MM (8–10) and ignores evidence of its therapeutic benefit for treating certain health conditions.(11–14) Less discussed has been the unusual regulatory vacuum the federal legal status creates for MM. Unlike other medicines, MM has not gone through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval process, and is not subject to the associated rules on drug efficacy testing, safety monitoring, labeling and marketing. The therapeutic use of marijuana is not subject to the strictures that apply to other scheduled medicines covered by the CSA, such as the requirement of a federal prescribing license and rules on supply chain security and accountability. While patient information, including prescriptions, is covered by federal patient privacy rules,(15) not all MM is provided as under prescription and it is unclear if this federal privacy protection applies to an illegal drug. Patients using MM are not protected from discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act, which does not prohibit discrimination based on current use of illegal use of drugs.(16)

In the absence of the usual federal regulations of controlled medicines, states are left to develop their own substitutes – or not. States traditionally regulate the marketing and use of legal drugs – tobacco and alcohol – that can cause harm to users and others. Perhaps because of this experience, and concerns about federal interference, early state MM laws typically covered matters that they had already dealt with in the realms of tobacco and alcohol (e.g. restrictions on use by minors, and restrictions on advertising).(2) As patients’ needs for a clearly defined dose of an uncontaminated product became more apparent, and the federal non-interference policy took shape, state MM laws began to explicitly address FDA-type issues like source and product safety.(2, 17) In this new area of health policy, states are again serving as “laboratories of democracy,”(18) but scientists evaluating these laws has focused on spillover effects of MM on recreational use and its harms (19–30), rather than on the ability of states to effectively regulate marijuana as a medicine.

There is tremendous interest in understanding the impact of these laws on the community. To assess impact, however, one must first have a clear understanding of what the law actually purports to allow or enable. Second, one must have a clear understanding of how the written law is being implemented or interpreted by the agents empowered by the law as well, and obeyed by those subject to it. Finally, one must have good measurement of an outcome that is meaningfully influenced by the law. This paper provides unprecedented clarity on the first step – the law as it is written -- by providing the first detailed scientific mapping of specific provisions of MM laws on the books at a particular point in time. As the discussion of medical and recreational marijuana laws have become blurred, previous analyses of the impacts of medical marijuana laws remain limited in their consideration of dimensions of these laws.(31–33) With few exceptions, (19, 22) studies of MM laws have grouped states as MM vs. non-MM, (20, 21, 23–30) ignoring the potentially important legal differences among MM states that can influence how the medical marijuana market operates, its size, and the likelihood that spillover effects to the nonmedical market occur.

This study sheds new light by providing greater detail of the variation that exists in terms of the laws on the books across the 50 states and Washington D.C., as they pertain to patient protections and requirements, product safety, and dispensary regulation. It shows how these states approaches compare to the standard Federal approach, identifying the degree to which particular states adopted a true “medical” approach to their law. It therefore lays the groundwork for studies evaluating implementation, compliance and evaluating the potential impacts of these laws on medical access, nonmedical use, benefits and harm.

Methods

Two legal researchers at the Public Health Law Research national program office of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation systematically collected and redundantly coded state MM laws effective on January 1, 2014 to create three empirical legal datasets: rules for patients, product safety and dispensaries. A third legal researcher oversaw the research and implemented quality control protocols. The datasets were subsequently extended back to July 1, 2009 and updated to 2017 by legal researchers of the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (PDAPS), using the same methods. This study presents cross-sectional analyses of laws in effect on February 1, 2017.

State laws were included if they established comprehensive MM programs permitting the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes without restriction based on tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) level. THC is the psychoactive component of cannabis. Included programs remove criminal penalties for the use of MM by patients diagnosed with a qualifying disease as determined by state law. States with laws allowing limited use of MM -- such as authorizing of cannabidiol (CBD, the plant extract and non-psychoactive extract component of cannabis), hemp extract or low-THC cannabis preparations -- were coded as not authorizing use of MM.

State laws were identified using key word searches and table-of-contents review on Westlaw and LexisAcademic, HeinOnline, and state-specific legislative websites. Redundant research, and comparison with secondary sources (the website http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/ and the National Conference of State Legislatures) were used to verify that all relevant laws and regulations were collected. The legal researchers analyzed samples of the collected legal texts to define a list of variables and create coding schemes, under the guidance of an expert in MM policy (R.P.). Using an iterative process designed to produce stable, accurate and reproducible observations, (34, 35) statutes and regulations were redundantly coded by the legal researchers in batches of ten states using MonQcle™ policy surveillance software (http://www.Monqcle.com/; http://www.webcitation.org/6qv5N1u0I). Coding was compared by the supervisor at the end of each batch, and a divergence rate was calculated (total # of divergent codes/total records coded by one coder). The team then met and the discrepancies were discussed and attributed to coder error, ambiguous coding questions or ambiguous legal texts. Corrections, question revisions and coding conventions were made as necessary and recorded in the research protocols. Once a coding batch achieved a discrepancy rate of <5%, only 20% of records were redundantly coded in succeeding batches. Researchers conducted a final statistical quality check (SQC) of a randomly selected set of variables based on an expected error rate of 20%. The SQC error rates were: 2.6% (rules for qualifying patients), 2.25% (product safety) and 1.42% (dispensaries). Full longitudinal datasets, codebooks and protocols describing the methods in detail are available on the PDAPS website (http://www.pdaps.org/; http://www.webcitation.org/6qv5CZNaZ). A fourth dataset, not included in this study, contains state-level laws regulating marijuana care givers and is also available on the PDAPS website.

Results

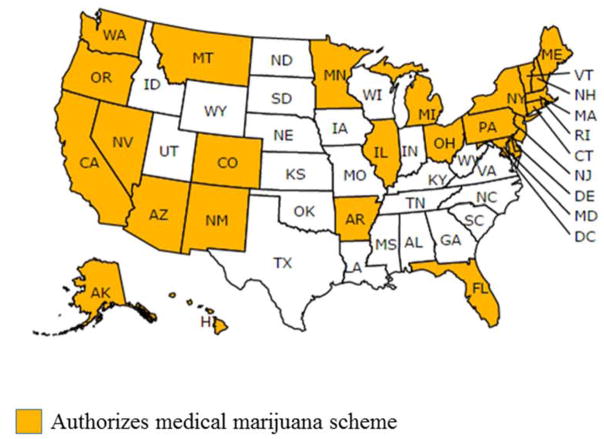

As of February 1st, 2017, lawmakers in 27 states and Washington, D.C (55% of states) have legalized MM use in comprehensive programs (Figure 1). (We will include Washington, D.C. within the count of “states” for the remainder of this article, and the denominator for the percentages reported will be 28, the number of states that have legalized MM.) MM states are clustered in the northeast, east north central and western United States. Florida and Arkansas are the only southern states that have legalized MM. Legislators in several southern states have passed laws allowing for low THC and high CBD strains of marijuana to be used for medicinal purposes, but these laws do not meet our definition of a comprehensive MM scheme. State MM laws address patient registration; qualifying diseases and symptoms; patient privacy and discrimination protections; cultivation; use restrictions; product testing; distribution site features; waste protocols; packaging/labeling requirements; dispensary density and zoning restrictions; dispensary product supply sources; and, dispensary stock amount limits. Details of current laws addressing each of these dimensions are included in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Comprehensive Medical Marijuana Laws in Effect as of February 1, 2017

Table 1.

Regulating Medicine: Federal vs. state policy strategies

| Regulation | Federal | State |

|---|---|---|

| Drug indication | FDA approval; off-label use permitted | Requires qualifying disease/symptom to be eligible for MM (27 states, 96%) |

| Drug efficacy | Animal and human clinical trials required for FDA approval | N/A |

| Drug safety | Animal toxicity testing, mandatory safety reporting to FDA during all phases of human testing and post-approval safety monitoring period | Mandates product safety testing for all MM products prior to sale (18 states, 64%) |

| Patient privacy | HIPAA | All states protect MM patient privacy to some degree |

| Patient discrimination protection | Americans with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination based on physical impairment | Explicitly protects MM patients from discrimination (14 states, 50%) |

| Restricted use locations | N/A | Prohibits MM use in specified locations/facilities/situations (26 states, 93%) |

| Grounds for denying treatment | N/A | States explicitly authorize permit revocation (24 states, 86%) |

| Site safety features | Controlled Substances Act addressing supply chain security | Explicit site structural requirements (24 states, 86%) |

| Product dispensary restrictions | Controlled Substances Act addressing supply chain, storage and reporting of purchases and sales | Number of dispensaries per state (18 states, 64%), location (21 states, 75%), stock amount (11 states, 39%) |

| Product supply source | FDA secure supply chain regulations under Controlled Substances Act | Regulates dispensary supply source (25 states, 89%) |

| Product labeling | Requires adherence to FDA label requirements | Explicitly regulates MM product labels (23 states, 82%) |

| Product packaging | FDA packaging regulations | Explicit package requirements and/or restrictions (21 states, 75%) |

| Medical waste (unused medicine) | Controlled Substances Act regulating disposal of unused medication | Explicit waste protocols (21 states, 75%) |

Patient Registration and Civil Rights Laws

Although not a common element of early laws adopted before 2009, when the U.S. Department of Justice first articulated explicit guidelines for limited federal toleration of state MM laws (36), by February 2017 all states except Florida require MM patient registration. Florida’s law requires the Department of Health to set up a registration system as part of its implementation of the scheme. Twenty-four states (86%) explicitly authorize permit revocation. Grounds for revocation include any failure to adhere to the MM law (16 states, 57%); fraud (12 states, 43%), for-profit sale (11 states, 39%), distribution to non-MM user (11 states, 39%), failure to update registration (10 states, 36%), and physician voiding of the MM prescription (10 states, 36%). All states except Washington D.C. have listed specific diseases qualifying for MM. Qualifying disease diagnoses vary across states (Table 3), and 22 states (79%) have a procedure for adding additional qualifying diseases through patient/public/physician petition(s), physician prescription, public hearings, or health department approval. Fifteen states (54%) permit patients to cultivate MM. MM laws in all states protect patient privacy, but only 14 (50%) protect patients against discrimination in employment, parental rights, property rights and/or education. Eight (29%) states authorize non-resident MM participants registered in other states to use MM.

Table 3.

Qualifying conditions for MM by state effective February 1, 2017

| State | Arthritis | PTSD | Cancer | Glaucoma | HIV | AIDS | Hepatitis C | Epilepsy | Multiple Sclerosis | Crohn’s disease | Alzheimer’s disease | Anorexia | Hospice Patients | Cachexia | Parkinson’s disease | Tourette Syndrome | ALS | Huntington’s disease | Inflammatory bowel disease | Muscular Dystrophy | Traumatic brain injury | Wasting Syndrome | Pain | Severe nausea | Seizures | Severe muscle spasms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AK | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| AR | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| AZ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| CA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| CO | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| CT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| DC* | Not Applicable | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DE | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| FL | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| HI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| IL | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| MA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| MD | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| ME | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| MI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| MN | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| MT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| NH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| NJ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| NM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| NV | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| NY | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| OH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| OR | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| PA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| RI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| VT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| WA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

DC authorize the use of MM for any illness or symptom in which a physician recommends marijuana will provide relief.

All states except Ohio and Florida place limitations on the location of MM use. Twenty-three (82%) states prohibit use in public places generally or in “plain view.” Five states (18%) specifically prohibit use on public beaches, eight (29%) in public parks and fifteen (54%) on public transit. Montana bans use at places of worship. Eleven states (39%) prohibit use in the workplace. Places where children congregate are precluded in many states: schools (22 states, 79%); childcare facilities (5 states, 18%); and youth centers (11 states, 39%). Five states (18%) bar any use in the presence of a minor. Other restricted locations include correctional facilities (20 states, 71%) and licensed drug treatment facilities (4 states, 14%). Five states (18%) limit use in health-care facilities.

Product Safety, Labeling and Packaging

Most states have laws requiring some form of product safety testing (22 states, 79%), which can include contaminant and/or pesticide testing and/or cannabinoid profiling. Eighteen (64%) states require some type of testing of all MM products before they may be sold. The remaining four (14%) states only require testing at the request of the state regulatory agency following complaint or reason to believe contamination has occurred. In the absence of federal guidance, standards for testing can and do differ. It should also be noted that this is safety testing of the product itself. No states have tested, nor require tests on, the safety of MM in vivo, despite a limited evidence base on how MM is metabolized, how it interacts with other medicines or whether it poses higher risks for certain patient populations.(12, 13)

Nearly all MM states have product labeling requirements (23 states, 82%), but there is little consistency in the labeling requirements themselves. Labeling rules in state law include listing the amount of usable marijuana (20 states, 71%), product potency (20 states, 71%), dispensary identification (17 states, 61%), strain of marijuana (9 states, 32%), ingredients for edibles (12 states, 43%), warning for medical use only (12 states, 43%), warning to abstain from operating machinery (11 states, 39%), health risks (10 states, 36%), proof of contaminant testing (7 states, 25%), lack of FDA approval (6 states, 21%), compliance with other federal or state law(s) (7 states, 25%), and instructions for use (6 states, 21%).

Twenty-one (75%) states regulate MM packaging, but, as with labeling, the rules vary. Requirements include tamper-proof packaging (14 states, 50%), child-proof (or child-resistant) packaging (15 states, 54%), opaque packaging (9 states, 32%), compliance with federal or state laws (6 states, 21%), plain packaging (5 states, 18%) and re-closable packaging (4 states, 14%). Nineteen (68%) states have product packaging (trade dress) restrictions, including anything typically designed to attract minors (14 states, 50%), “false or misleading” statements (13 states, 46%), cartoons (11 states, 40%), depictions of minors (8 states, 29%), pictures of marijuana (6 states, 21%), packaging that resembles that of candy (6 states, 21%), and/or anything prohibited by state health or safety code (Maine). Details related to the implementation and enforcement of these regulations, such as specification of a responsible agency, rules regarding the frequency/conduct of compliance checks, and penalties for violators, are not consistently addressed within these statutes.

Dispensary and Other Distribution Site Regulations

Twenty-five (89%) states regulate the operation of dispensaries, including product source (25 states, 89%) and stocking levels (11 states, 39%). Authorized sources include self-cultivation (15 states, 54%), other dispensaries (9 states, 32%), licensed cultivators (10 states, 36%), caregivers (5 states, 18%), and qualified patients (4 states, 14%). Eleven (39%) states set stock amount limits. Stock limits are computed on quantity of usable marijuana (8 states, 29%), number of mature plants (6 states, 21%), number of immature plants (5 states, 14%), and/or number of plants regardless of maturity (Hawaii and Massachusetts).

Dispensary location is also commonly regulated or designated for local regulation. Twenty (71%) states permit local zoning restrictions on dispensaries, and 18 (64%) states limit the total number of dispensaries allowed to operate within the state. Twenty-one (75%) states have restriction on dispensary location. The most common location restrictions for dispensaries were based on proximity to schools (20 states, 71%) and daycare facilities (11 states, 39%). Other facilities triggering dispensary location restrictions included churches (6 states, 21%), colleges (Colorado), recreational centers (District of Columbia, Nevada, and Washington), group care homes (Illinois), drug-treatment facilities (Colorado) and other dispensaries (Oregon). Departments assigned regulatory oversight over dispensaries include health departments (AZ, DC, DE, HI, MA, ME, MN, NJ, NH, NM, NY, NV, OR, PA, RI), Consumer Protection (CA, CT), Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (MI), Revenue (CO), Public Safety (VT), and Board of Pharmacy (OH).

Twenty-four (86%) states have explicit structural requirements for dispensaries and/or other facilities in the MM supply chain, such as cultivation and distribution sites. Related both to safety and security, these include maintaining a security system (21 states, 75%), using secure, locked spaces accessible only to cardholders and/or authorized employees (18 states, 64%), hand washing stations (10 states, 36%) and/or ventilation systems (6 states, 21%). Twenty-one (75%) states have waste disposal regulations. These include requirements to keep a record of waste disposal (19 states, 68%), destroy waste (16 states, 57%), transfer waste to law enforcement (5 states, 18%) or deliver waste to a state agency (Connecticut).

Discussion

State MM laws allow the therapeutic use of a drug that has not been tested for safety and efficacy under FDA rules. Unlike FDA-approved medications, there is no assurance of national standardization in the doses and ingredients, or that the products have been manufactured in safe conditions. Patients being treated with FDA-approved prescription drugs in conventional healthcare settings enjoy some protection under federal law of their privacy and from discrimination based on their use of a drug to treat a disability. To prevent counterfeiting and diversion, controlled medicines are strictly tracked from factory to pharmacy, and physicians who prescribe controlled substances are required to have a special license to do so. None of these taken-for-granted national regulatory assurances apply to MM. The federal refusal to adjust the scheduling of marijuana has resulted in a state patchwork quilt of differing and even conflicting rules to fill the gap.

States are also legislating to address the risk of social side effects from MM sale and use, such as traffic accidents due to “drugged driving,” increased emergency room visits and improper youth access.(37–41) Legislators are drawing on regulatory models developed to control alcohol and tobacco.(42) As with state plugging of federal regulatory gaps, there is little consistency in the detailed requirements or the assignment of monitoring and enforcement authority. Whether and how the laws are actually enforced was not evaluated here, but implementation studies are an important next step for researchers.

More than half the states have decided that marijuana should be available for therapeutic purposes. The link between MM and a political movement to reduce or eliminate legal restrictions on recreational marijuana is beyond the scope of this study. We can say that all eight states that have adopted legalization policies as of January 2017 were states that previously allowed medical marijuana(43) and had decriminalization policies in place for non-medical use.(2)

State MM laws, whatever their impetus, have tried to varying degrees address the regulatory hole created by the inability of the FDA to regulate this medication nationally. Serious deficiencies in this state efforts would add to the rationale for federal rescheduling and the integration of marijuana into the standard controlled substances and pharmaceutical regulatory framework. If, on the other hand, states are able to successfully manage the safe use and distribution of a new pharmaceutical product, critics of federal oversight of the pharmaceutical industry would have an interesting case study to ponder.

The best approach to protecting patients and the public from the risks associated with MM is still unknown, as research is only now documenting in detail the differences across states in their regulatory approaches. Work is also ongoing to document important local-level regulatory variation. More work is needed to document the extent to which the variation in laws on the books translates into meaningful implementation and practice variation. Certainly the U.S. marijuana decriminalization literature has clearly demonstrated that differences in laws on the books do not necessarily translate into meaningful differences in arrests.(44)

With knowledge of the legal differences, and whether they translate into real differences in enforcement, it will then be possible to truly understand the impact of these laws on outcomes.

There is an extraordinary policy experiment underway with little acknowledgement of the regulatory variation that exists across and even within states. The data presented here captures the variation in state MM law at a detailed level, focusing on particular domains relevant for medical access. We ignore in this paper general areas of these laws that have evolved outside of the need for patient access in 2017, such as cultivation, as the evolution of other state laws (namely legalization) now shape the state-federal conflicts in this space. The substantial variation over time and across jurisdictions in MM dimensions reported here provides an opportunity for rigorous quasi-experimental studies to test state policy approaches to date and illuminate the policy choices ahead. The current diversity of state regulatory strategies provides an ideal opportunity to assess correlations with desired and undesired outcomes; the evaluation of these laws is the logical next step in this line of research, including assessments of how they are implemented and whether these differences across states translate into changes in both behavior and health outcomes.

Our data also provide the material needed for the construction of a medical marijuana policy index. A valid composite indicator of these laws (as has been devised in the alcohol domain, for example (45)) can only be created when we have some sense of the relative importance of specific dimensions of the policy. While researchers have begun to consider specific elements of medical marijuana laws (e.g. dispensary or home cultivation) they have yet to consider other elements of these laws that work in the tobacco/alcohol field suggest may be relevant when looking for public health effects (e.g. taxation, outlet density, bans). Future research on specific policy components measured in our data can be used to validate the components of an index.

Limitations

The study does not include state laws that permit use of only of CBD oil or low THC marijuana preparations for therapeutic purposes. As of March 1, 2017, 16 states that do not have a comprehensive MM program have passed laws permitting the use of low THC/high CBD products for medical reasons in limited situations.(46) This study only observed the law as written in statutes and regulations. Actual practice may differ from the law on the books. For example, police may not actually enforce restrictions on places of use, or regulatory agencies may lack staff to monitor compliance with packaging rules. Finally, state-level mapping cannot capture more specific requirements that may be imposed at the county or municipal level.

Conclusion

Federal scheduling of marijuana as a drug with no therapeutic use has resulted in a patchwork of state laws and hampered research efforts, resulting in a “medicine” without well-tested efficacy, standardized dosing, safety standards, or clear clinical guidelines. MM states have enacted a myriad of laws that mimic some aspects of federal prescription drug and controlled substances laws; they have drawn on regulatory strategies used to deal with the externalities of alcohol and tobacco; and, in some cases, have enacted regulations that go beyond those traditionally applied to medicines (i.e. patient registration, qualifying diagnoses and registration revocation). Only rigorous evaluation research, which the data presented here were created to facilitate, can determine which, if any, of the regulatory strategies states have adopted are succeeding in governing MM as a safe and effective medicine the use of which is compatible with the public’s health and safety.

Table 2.

Patient, product safety and dispensary laws by state effective February 1, 2017

| State | Patient | Product Safety | Dispensary | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Requires qualifying diagnosis | Requires patient registration | Requires risk-benefit disclosure | Permits registration revocation | Permits patient cultivation | Protects patient privacy | Protects against discrimination | Requires safety testing for all MM | Requires site safety features | Regulates product packaging | Regulates product labeling | Specifies MM waste protocol | Limits dispensary density | Restricts dispensary locations | Permits local zoning | Regulates product supply source(s) | Limits dispensary stock amount | |

| AK* | X | X | X | X | X | Not Applicable | |||||||||||

| AR | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| AZ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| CA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| CO | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| CT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| DC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| DE | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| FL* | X | X | Not Applicable | ||||||||||||||

| HI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| IL | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MD | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| ME | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| MI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| MN | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| MT* | X | X | X | X | X | X | Not Applicable | ||||||||||

| NH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| NJ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| NM | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| NV | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| NY | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| OH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| OR | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| PA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| RI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| VT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| WA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

AK, FL, MT, do not regulate MM dispensaries

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (contract # HHSN271201500081C) and the Public Health Law Research and Policy Surveillance Programs of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundations. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and not the funding agencies. The authors thank Heidi Grunwald, PhD, for her assistance in statistical quality control process, and the following legal researchers who have contributed to datasets or updates: Elizabeth Platt, Sterling Johnson, Caitlin Davie, Alexander Frazer, Lindsay Cloud, Andrew Kunka and Nicolas Wilhelm.

Footnotes

Declarations of competing interests: None

References

- 1.Vitiello M. Proposition 215: De facto legalization of pot and the shortcomings of direct democracy. U Mich JL Reform. 1997–1998;31(3):707–76. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacula RL, Smart R. Medical Marijuana and Marijuana Legalization. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2017;13(1):397–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. United States Drug Enforcement Administration; 2016. [cited 2016 June 1]; Available from: http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml; http://www.webcitation.org/6qv4MVD5s. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum S. Gonzales v. Raich: Implications for Public Health Policy. Law and the Public’s Health. 2005;120:680–2. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole JM. Memorandum. Washington, D.C: United States Department of Justice; 2013. Aug 29, Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act of 2015. S 538 113th Cong. 2015.

- 7.Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act of 2016. (2016);S. 542, 114th Cong.

- 8.Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, Kleiman M. Marijuana legalization : what everyone needs to know. 2. p. xvi.p. 284. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annas G. Medical Marijuana, Physicians, and State Law. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):983–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler JN, Colbert JA. Clinical decisions. Medicinal use of marijuana--polling results. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):e30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde1305159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch ME, Ware MA. Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: An Updated Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2015;10(2):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s11481-015-9600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Academy of Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids : the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, Bronstein J, Youssof S, Gronseth G, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1556–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (“HIPAA”), Pub. L. No. Pub. L. 104–191(August 21, 1996, 1996).

- 16.Rendall R. Medical Marijuana and the ADA- Removing Barriers to Employment for Disabled Individuals. Health Matrix: The Journal of Law-Medicine. 2012;22(1):315–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams AR, Olfson M, Kim JH, Martins SS, Kleber HD. Older, Less Regulated Medical Marijuana Programs Have Much Greater Enrollment Rates Than Newer ‘Medicalized’ Programs. Health Affairs. 2016;35(3):480–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferraiolo K. State Policy Innovation and the Federalism Implications of Direct Democracy. Publius: The Journal of Federalism. 2007;38(3):488–514. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Cummings JR. The effect of medical marijuana laws on adolescent and adult use of marijuana, alcohol, and other substances. J Health Econ. 2015;42:64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mark Anderson D, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical Marijuana Laws and Teen Marijuana Use. American Law and Economics Review. 2015;17(2):495–528. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasin DS, Wall M, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, et al. Medical marijuana laws and adolescent marijuana use in the USA from 1991 to 2014: results from annual, repeated cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):601–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sevigny EL, Pacula RL, Heaton P. The effects of medical marijuana laws on potency. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(2):308–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris RG, TenEyck M, Barnes JC, Kovandzic TV. The effect of medical marijuana laws on crime: evidence from state panel data, 1990–2006. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masten SV, Guenzburger GV. Changes in driver cannabinoid prevalence in 12 U.S. states after implementing medical marijuana laws. Journal of Safety Research. 2014;50(0):35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu YW. The effects of medical marijuana laws on illegal marijuana use. J Health Econ. 2014;38:43–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choo EK, Benz M, Zaller N, Warren O, Rising KL, McConnell KJ. The impact of state medical marijuana legislation on adolescent marijuana use. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(2):160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynne-Landsman SD, Livingston MD, Wagenaar AC. Effects of state medical marijuana laws on adolescent marijuana use. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1500–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI. Medical marijuana laws, traffic fatalities, and alcohol consumption. Journal of Law and Economics. 2013;56(2):333–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cerda M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1–3):22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011. Epub 2011/11/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachhuber MA, Saloner B, Cunningham CO, Barry CL. Medical cannabis laws and opioid analgesic overdose mortality in the united states, 1999–2010. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(10):1668–73. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pacula RL, Hunt P, Boustead A. Words Can Be Deceiving: A Review of Variation Among Legally Effective Medical Marijuana Laws in the United States. J Drug Policy Anal. 2014;7(1):1–19. doi: 10.1515/jdpa-2014-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pacula RL, Powell D, Heaton P, Sevigny EL. Assessing the Effects of Medical Marijuana Laws on Marijuana Use: The Devil is in the Details. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2015;34(1):7–31. doi: 10.1002/pam.21804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritter A, Livingston M, Chalmers J, Berends L, Reuter P. Comparative policy analysis for alcohol and drugs: Current state of the field. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2016;31:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krippendorff K. Validity in Content Analysis. In: Mochmann E, editor. Computerstrategien fuer die kommunikationsanalyse. Frankfurt: Campus-Verlag; 1980. pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson E, Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC. Measuring Statutory Law and Regulations for Empirical Research. In: Wagenaar A, Burris S, editors. Public Health Law Research: Theory and Methods. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. pp. 237–60. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogden DW. Investigations and Prosecutions in States Authorizing the Medical Use of Marijuana. Washington, DC: United States Department of Justice; 2009. Oct 19, Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monte AA, Zane RD, Heard KJ. THe implications of marijuana legalization in colorado. JAMA. 2015;313(3):241–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larkin PJ., Jr Medical or recreational marijuana and drugged driving. Am Crim L Rev. 2015;52:453–1659. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salomonsen-Sautel S, Min S-J, Sakai JT, Thurstone C, Hopfer C. Trends in fatal motor vehicle crashes before and after marijuana commercialization in Colorado. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;140:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caplan G. Medical marijuana: A study of unintended consequences. McGeorge L Rev. 2012;43:127. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(7):630–3. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, Chaloupka FJ, Caulkins JP. Developing Public Health Regulations for Marijuana: Lessons From Alcohol and Tobacco. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(6):1021–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kilmer B, Pacula RL. Understanding and learning from the diversification of cannabis supply laws. Addiction. 2016 doi: 10.1111/add.13623. n/a-n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pacula R, MacCoun R, Reuter P, Chriqui JF, Kilmer B, Harris K, et al. What does it mean to decriminalize cannabis? A cross-national empirical examination. In: Lindgren B, Grossman M, editors. Substance Use: Individual Behavior, Social Interactions, Markets and Politics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 347–70. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, Nguyen T, Oussayef N, Heeren TC, et al. A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Conference of State Legislatures. State Medical Marijuana Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2017 [updated March 1, 2017; cited 2017 March 14]; Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx; http://www.webcitation.org/6qv4nUpXN.