Abstract

Objectives

Less is known about the respiratory health of general farming and non-framing populations. A longitudinal Saskatchewan Rural Health Study (SRHS) was conducted to explore the association between individual and contextual factors with respiratory health outcomes in these populations. Hence, the objectives are to: (i) describe the updated methodology of longitudinal SRHS—an extension of baseline survey methodology published earlier; (ii) compare baseline characteristics and the prevalences of respiratory health outcomes between drops-outs and completers; and (iii) summarize key findings based on baseline survey data.

Results

The SRHS was a prospective cohort study conducted in two phases: baseline survey in 2010 and a follow-up in 2014. Each survey consisted of two components, self-administered questionnaire and clinical assessments. At baseline, 8261 participants (≥ 18 years) (4624 households) and at follow-up, 4867 participants (2797 households) completed the questionnaires. Clinical assessments on lung functions and/or allergies were conducted among a sub-group of participants from both the surveys. To date, we published 15 peer-reviewed manuscripts and 40 abstracts in conference proceedings. Findings from the study will improve the knowledge of respiratory disease etiology and assist in the development and targeting of prevention programs for rural populations in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-017-3047-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rural, Small town, Respiratory, Asthma, Chronic bronchitis, Longitudinal, Farming, Non-farming

Introduction

The longitudinal Saskatchewan Rural Health Study (SRHS) was conducted in 2010 and 2014 in the province of Saskatchewan, Canada. Its primary aim was to explore the hypothesis that individual (cigarette smoke, obesity) and contextual factors (socio-economic, access to health services), are associated with respiratory outcomes of asthma, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung function, after controlling for principal covariates (age, gender). Evidence about adverse respiratory effects in agricultural populations including asthma, reductions in lung function, acute inflammatory responses, and other respiratory symptoms has mainly been derived from studies of swine and poultry workers [1–16]. Studies of grain elevator workers have also demonstrated similar detrimental respiratory effects [17–20]. Although inferences may be drawn from these selected worker populations, less is known about the respiratory status of more general farming and non-farming populations [21].

In response to these gaps in knowledge, we had the opportunity to conduct a longitudinal, population-based study to assess possible determinants of respiratory health among rural farming and non-farming people in the province of Saskatchewan. The SRHS [21] was designed using population health framework (PHF) to address observed gaps in the literature regarding respiratory health of farm and non-farm populations [22]. This theory guided the systematic exploration of how individual and contextual risk factors influence respiratory health outcomes in such contexts. The overall purpose of the SRHS was to examine rural environments, defined broadly, as determinants of respiratory health outcomes in rural people. It had two core objectives: to estimate the strengths of relationships between various determinants and respiratory health outcomes in farmers and small town dwellers, and to conduct a prospective cohort evaluation of respiratory health outcomes in farmers and small town dwellers. However, the objective of this report is to: (i) describe the updated methodology of longitudinal SRHS—an extension of baseline survey methodology published earlier; (ii) compare baseline characteristics and the prevalences of respiratory health outcomes between drops-outs and completers; and (iii) summarize key findings based on baseline survey data.

Main text

The SRHS involved a prospective cohort conducted in two phases: the baseline survey and a 4-year follow-up survey. Prior to the commencement of baseline survey, a pilot study was conducted to optimize the content and administration of the baseline questionnaire [23]. Pilot project responses guided us to modify several questions in the baseline survey questionnaire.

The rural municipal and small town councils provided the taxation lists to the project manager, which were used to compile a registry of mailing addresses [21]. We sampled a population of 11,982 tax paying households to create a database of study population based on sample size calculations and assuming 30% response rate [24]. To maximize the response rates for both baseline and follow-up surveys, we adopted a modified version of the Dillman total design method for mail and telephone surveys [25] in the administration of questionnaires. Dillman’s method comprises of a series of mail contacts with the prospective study participants. In both surveys: (i) study packages contained a letter of invitation, an information pamphlet, and the questionnaire so that recruitment and data collection occurred simultaneously; (ii) these study packages were addressed personally and sent via first class mail to all households; and (iii) a key informant in each household was asked to provide household level information and then to complete a section for each adult living in the household.

Questionnaire development

Our study and questionnaire instrument were based on the theoretical framework of Health Canada’s Population Health Framework. It’s mentioned in our earlier manuscript [21] that “A panel consisting of the SRHS research team and two community members (one from a RM and one from a small town) developed the study questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to include key measures required to test the population health framework (PHF)” [21]. Some questions were modified in context of the rural populations. Questions in the instruments (household and individual questionnaires) were adopted from our previous work with rural populations, and from other researchers’ questionnaires (for example income question and access to health care related questions from Statistics Canada survey questionnaires; excessive daytime questions from Epworth Sleepiness Scale questionnaire; and Occupational history related questions from the Cross-Canada study of pesticides and health etc.)

Study design for adult baseline survey

For the baseline survey the study design is explained in detail in our earlier publication entitled ‘The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study: an application of a population health framework to understand respiratory health outcomes’ [21]. Briefly, SRHS baseline component consisted of three stages, which consisted of: recruitment of populations in rural municipalities (RMs) and small towns (stage 1); self-administration of mailed out household and individual questionnaires to the target populations in order to assess contextual and individual factors listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 (stage 2); and obtaining clinical assessments (anthropometric measures, lung function measurements, and allergy testing-see Additional file 1: Table S1) on a sub-population that completed the questionnaires (stage 3).

Study design for adult follow-up survey

Those who participated in the baseline were followed-up after 4 years and data on individual and contextual factors listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 were collected via mailed-out self-administered questionnaires. Clinical assessments (see Additional file 1: Table S1) were obtained by contacting all those participants who participated in the clinical component of the baseline survey. In order to maintain a high retention rate for the follow-up study, in the interim we remained in touch with the study participants via regular local newsletters/newspapers, and presented results at local council meetings, and other communications with the rural media.

Clinical assessments at baseline and follow-up surveys

Those who responded positively to the final question (‘would you be willing to be contacted about having breathing and/or allergy tests at a nearby location?’) on the baseline questionnaire were sent a letter of invitation to participate in a clinical assessment. Those who participated in the baseline clinical assessments were contacted and followed-up after 4 years. At both surveys, clinical measurements included the measurement of height, weight, blood pressure, forced expired volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC ratio, and maximum mid-expiratory flow rate (FEF25–75) and allergy skin prick tests for six allergens. Sensormedics (Anaheim, CA) dry rolling seal spirometers were used for pulmonary function testing [5, 8] and measurements were taken according to standards of the American Thoracic Society criteria [26]. The protocol used to obtain these measurements is described in detail elsewhere [21].

Study populations

The study populations consisted of the Farm Cohort and the Small Town Cohort recruited from the four quadrants [Northwest (NW), Northeast (NE), Southwest (SW), and Southeast (SE)] of Saskatchewan [21]. Thirty-two rural municipalities (9 from the NW, 8 from each of the NE and SW, and 7 from SE) and 15 small towns (6 from the NW, 2 from the NE, 4 from SW, and 3 from SE) participated in the phase 1—baseline survey. Questionnaires were mailed to 11,004 households in 2010 [21]. Phase 2—follow-up survey was conducted in 2014 and consisted of mailed questionnaires and clinical assessments of individuals who participated in the phase 1—baseline survey. In the follow-up survey, an initial mailing was administered to 4624 households, of which 4454 were deemed eligible (170 letters were returned to the sender).

Response rates for baseline and follow-up surveys

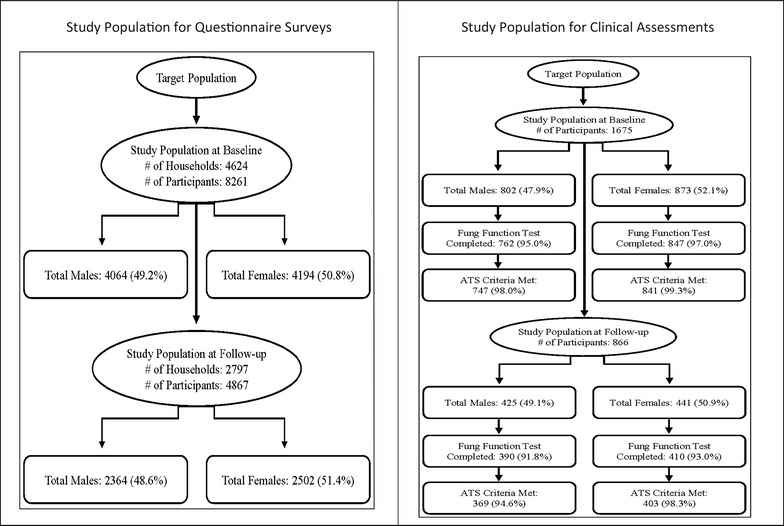

The response rates for both surveys are provided in Table 1. The response rate of baseline mail-out questionnaire survey was 42%. We obtained completed questionnaires from 4624 households including information about 8261 individuals, 18 years and older (see Fig. 1). In the follow-up survey, questionnaires were returned from 2797 households comprised of 4867 individuals. Of these, 4741 individuals had participated at both time points. There were 126 new individuals who did not participate in the baseline survey but were included at follow-up (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Response rates for the Saskatchewan Rural Health Study in the 2010 baseline and 2014 follow-up surveys

| Baseline (2010) | Follow-up (2014) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small town (n = 15) | RM (n = 32) | Small town (n = 15) | RM (n = 32) | |

| Household addresses (ratepayers) baseline: n = 11,004 Follow-up: n = 4454 |

5318 | 5683 | 2124 | 2330 |

| Household returned surveys, n (%) | 2800 (52.7) | 2910 (51.2) | 1487 (70.0) | 1662 (71.3) |

| No response, n (%) | 2518 (47.3) | 2773 (48.8) | 637 (30.0) | 668 (28.7) |

| Response rate (based on household addresses) n (%) Baseline: n = 4624a Follow-up: n = 2797 |

2242 (42.2) | 2380 (41.9) | 1279 (60.2) | 1518 (65.1) |

| Persons participating Baseline: n = 8261b Follow-up: n = 4741 |

3785 | 4472 | 2050 | 2691 |

| Age (mean + SE) | 56.3 + 0.28 | 55.9 + 0.22 | 61.4 ± 0.3 | 61.0 ± 0.3 |

| Male:female ratio | 1774/2007 | 2292/2179 | 930/1120 | 1375/1316 |

| Clinical assessments Baseline: n = 1675 Follow-up: n = 885 |

||||

| Lung function, n (%) | 679 (40.4) | 930 (55.3) | 356 (40.2) | 460 (52.0) |

| Allergy test, n (%) | 686 (40.8) | 929 (55.3) | – | – |

| Both, n (%) | 653 (38.8) | 896 (53.3) | – | – |

aTwo households were not identified in baseline

bFour individuals were not identified by town/RM

–, data not collected

Fig. 1.

Saskatchewan Rural Health Study: derivation of sample for questionnaire and clinical assessments. Study population for questionnaire and clinical assessments

Response rates for clinical assessments

At baseline, 1675 individuals (802 males and 873 females) gave consent to participate in the clinical assessment component. Of these, 1609 (762 males and 847 females) completed the lung function testing and 1565 (738 males and 827 females) lung function tests met the ATS criteria [26]. Individuals who gave consent to participate in the clinical assessment component at baseline were contacted in 2014 asking their willingness to participate in the clinical component again. Eight hundred sixty-six individuals agreed to participate in lung function testing at the follow-up survey. Of these, 800 (390 males and 410 females) completed the lung function testing and 772 (369 males and 403 females) lung function tests met the ATS criteria (see Fig. 1).

Comparison of completers vs. drop-outs

There were 4741 people who participated in both surveys (completers) and 3520 who did not participate in the follow-up survey (drop-outs). For the clinical component, 800 of the respondents completed the clinical testing at baseline and follow-up survey and 809 drop-outs did not participate in clinical testing in the follow-up survey. A comparison of baseline characteristics of completers and drop-outs is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between completers (who participated in both surveys) vs. drop-outs (who participated only in the baseline survey)

| Completers (n = 4741) | Drop-outs (n = 3520) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadranta | 0.23 | ||

| Southwest | 854 (18.0) | 684 (19.5) | |

| Southeast | 1016 (21.4) | 776 (22.1) | |

| Northeast | 1391 (29.3) | 1009 (28.7) | |

| Northwest | 1480 (31.2) | 1047 (29.8) | |

| Rural municipalitya, n (%) | 0.0001 | ||

| Town | 2050 (43.2) | 1735 (49.4) | |

| RM | 2691 (56.8) | 1781 (50.7) | |

| Location of homea, n (%) | 0.0001 | ||

| Farm | 2127 (45.1) | 1318 (37.8) | |

| Non-farm | 2593 (54.9) | 2170 (62.2) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.21 | ||

| Male | 2305 (48.6) | 1759 (50.0) | |

| Female | 2436 (51.4) | 1758 (50.0) | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.0001 | ||

| 18–45 | 893 (18.8) | 1051 (29.9) | |

| 46–55 | 1261 (26.6) | 787 (22.4) | |

| 56–65 | 1273 (26.9) | 675 (19.2) | |

| > 65 | 1314 (27.7) | 1004 (28.6) | |

| Mean ± S.E. | 57.0 ± 0.2 | 55.4 ± 0.5 | 0.002 |

| Socio-economic status | |||

| Income, n (%) | 0.0001 | ||

| Money left at end of montha | |||

| Some money | 2653 (61.7) | 1774 (56.4) | |

| Just enough money | 900 (20.9) | 695 (22.1) | |

| Not enough money | 749 (17.4) | 679 (21.6) | |

| Lowest income | 134 (3.3) | 190 (6.5) | 0.0001 |

| Lowest middle income | 624 (15.4) | 592 (20.3) | |

| Upper middle income | 1437 (35.3) | 868 (29.8) | |

| Highest income | 1871 (46.0) | 1261 (43.3) | |

| Educationa, n (%) | 0.0001 | ||

| ≤ grade 12 | 2716 (57.9) | 2225 (64.2) | |

| > grade 12 | 1979 (42.2) | 1239 (35.8) | |

| Respiratory health outcomes, n (%) | |||

| Cougha | 677 (14.4) | 558 (16.1) | 0.04 |

| Wheeze | 1886 (39.8) | 1471 (41.8) | 0.07 |

| Asthma | 386 (8.1) | 329 (9.4) | 0.05 |

| Chronic bronchitisa | 281 (6.0) | 202 (5.9) | 0.82 |

| COPDa | 91 (1.9) | 99 (2.9) | 0.006 |

| Lung function (mean ± S.E.) | |||

| Male | N = 577 | N = 185 | |

| FVC | 4.73 ± 0.04 | 4.67 ± 0.07 | 0.44 |

| FEV1 | 3.59 ± 0.03 | 3.53 ± 0.06 | 0.42 |

| FEV1/FVC*100 | 75.81 ± 0.31 | 75.36 ± 0.6 | 0.49 |

| FEF25–75 | 3.13 ± 0.05 | 3.07 ± 0.09 | 0.53 |

| Female | N = 644 | N = 203 | |

| FVC | 3.40 ± 0.03 | 3.43 ± 0.05 | 0.55 |

| FEV1 | 2.66 ± 0.02 | 2.67 ± 0.04 | 0.75 |

| FEV1/FVC*100 | 78.02 ± 0.2 | 77.6 ± 0.5 | 0.44 |

| FEF25–75 | 2.52 ± 0.04 | 2.52 ± 0.07 | 0.99 |

p values are reported from Chi square test (categorical variable) and t-test (continuous variable)

aTotal are not adding up to n because there are some missing values

Drop-outs were most likely to have the following characteristics relative to responders: town dwellers, lower socio-economic status in terms of income and education, and higher reported diagnoses of cough, wheeze, asthma, or COPD. No statistically significant differences for lung function values were observed between the two groups.

Main findings from baseline survey data

Major findings included associations of rural environments with chronic bronchitis, asthma, and decreased lung function. We also collected information on other chronic conditions (secondary outcomes) such as diabetes, mental health, excessive daytime sleepiness etc. We are currently analyzing longitudinal data collected at two time points. Important findings from the pilot study [23, 27] and baseline survey data [21, 28–39] are summarized in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Results based on baseline data have been presented at local, national and international scientific conferences. Forty abstracts have been published in conference proceedings. Two publications from the pilot study and 13 from the baseline survey have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Objectives and important finding of these manuscripts are summarized in Additional file 2: Table S2. Baseline survey data resulted in two MSc theses [40, 41] based on the adult data. Analyses of longitudinal data are ongoing.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the SRHS is the largest community based study of health in rural populations that has ever been conducted in Canada. We have successfully used Health Canada’s PHF [22] in other population-based epidemiological studies conducted by our research team. The PHF has been used in other two longitudinal studies: (i) the Saskatchewan Farm Injury Cohort Study [24] and (ii) the first nations lung health project [42]. The findings of baseline survey have provided important information about respiratory disease etiology. We have established a baseline for the prevalence of CB and asthma among rural farm and non-farm residents in Saskatchewan against which future developments in control of this disease can be measured. We can use this knowledge of respiratory disease etiology for the development and targeting of prevention and intervention programs for rural population of Saskatchewan.

Limitations

Strengths and limitations of the SRHS were mentioned in our methodology paper based on baseline survey [21]. There are weaknesses associated with the SRHS and its longitudinal design. As is the case for most designs of this type, it was expensive, time-consuming, and had challenges associated with missing-data due to attrition [43]. Complex methods will be required to analyze longitudinal data that would account for two-layers of complexities: within-household correlation (multiple individuals from the same household) and within-subject correlation (due to repeated observations) and these will be accounted for by using generalized estimating equations (GEE) [43] and robust variance estimation approaches. Additional complications due to missing data in longitudinal studies can be handled via GEE only if missing data are missing completely at random. Several statistical approaches to handle missing data with missing at random or missing not at random mechanisms have been proposed in the recent years [43].

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Questionnaire and clinical information collected at the baseline and follow-up surveys. Protocol.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Objectives and major findings of the manuscripts (based on pilot and baseline studies) published in peer-reviewed journals. Objectives and major findings.

Authors’ contributions

PP, WP, CPK, DR, JL, SK, BJ, NK and JD contributed to grant writing, development of study design, questionnaire development, and study coordination. JD and PP are the co-principal investigators of the SRHS study. CPK is the biostatistician and she supervised every stage of data entry and data cleaning. PP and CPK supervised statistical analyses. MR and KA conducted the statistical analyses for the current manuscript. PP prepared the manuscript and JD, WP, JL, DR, SK, BJ, NK and CPK significantly contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Team consists of: James Dosman, MD (Designated Principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK Canada); Punam Pahwa, Ph.D. (Co-Principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); John Gordon, Ph.D. (Co-Principal Investigator, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Yue Chen, Ph.D. (University of Ottawa, Ottawa Canada); Roland Dyck, MD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Louise Hagel (Project Manager, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon SK Canada); Bonnie Janzen, Ph.D. (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Chandima Karunanayake, Ph.D. (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Shelley Kirychuk, Ph.D. (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Niels Koehncke, MD (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Joshua Lawson, Ph.D., (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); William Pickett, Ph.D. (Queen’s University, Kingston ON Canada); Roger Pitblado, Ph.D. (Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury ON Canada); Donna Rennie, RN, Ph.D., (University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon SK Canada); Ambikaipakan Senthilselvan, Ph.D. (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada). We are grateful for the contributions of all the participants who donated their time to complete and return the survey.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Currently the data from the SRHS are not publically available. Anyone interested about the data can contact Dr. James Dosman (james.dosman@usask.ca) or Dr. Punam Pahwa (pup165@mail.usask.ca) for further details.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Before conducting the survey, a Certificate of Approval was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan’s Biomedical Research Ethics Board and conducting the in-person administration of questionnaires and clinical assessments, informed written consent from all participants was obtained.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research “Saskatchewan Rural Health Study”, Canadian Institutes of Health Research MOP-187209-POP-CCAA-11829.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- ATS

American Thoracic Society

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- GIS

geographic information system

- RM

rural municipalities

- SEHS

Saskatchewan Rural Health Study

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13104-017-3047-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Punam Pahwa, Phone: 1 (306) 966-8300, Email: pup165@mail.usask.ca.

Masud Rana, Email: masud.rana@usask.ca.

William Pickett, Email: pickettw@queensu.ca.

Chandima P. Karunanayake, Email: cpk646@mail.usask.ca

Khalid Amin, Email: khalid.amin@usask.ca.

Donna Rennie, Email: donna.rennie@usask.ca.

Josh Lawson, Email: josh.lawson@usask.ca.

Shelley Kirychuk, Email: shelley.kirychuk@usask.ca.

Bonnie Janzen, Email: bonnie.janzen@usask.ca.

Niels Koehncke, Email: niels.koehncke@usask.ca.

James Dosman, Email: james.dosman@usask.ca.

References

- 1.Dosman JA, Senthilselvan A, Kirychuk SP, et al. Positive human health effects of wearing a respirator in a swine barn. Chest. 2000;118(3):852–860. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cormier Y, Duchaine C, Israël-Assayag E, Bédard G, Laviolette M, Dosman J. Effects of repeated swine building exposures on normal naive subjects. Eur Respir J. 1997;10(7):1516–1522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10071516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA, Kirychuk SP, et al. Accelerated lung function decline in swine confinement workers. Chest. 1997;111(6):1733–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirychuk SP. Predictors of longitudinal changes in pulmonary function among swine confinement workers. Can Respir J. 1998;5(6):472–8. http://www.mendeley.com/research/predictors-longitudinal-changes-pulmonary-function-among-swine-confinement-workers/. Accessed Mar 14 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Senthilselvan A, Chénard L, Ulmer K, Gibson-Burlinguette N, Leuschen C, Dosman JA. Excess respiratory symptoms in full-time male and female workers in large-scale swine operations. Chest. 2007;131(4):1197–1204. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senthilselvan A, Zhang Y, Dosman JA, et al. Positive human health effects of dust suppression with canola oil in swine barns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2 Pt 1):410–417. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9612069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirychuk SP, Senthilselvan A, Dosman JA, et al. Respiratory symptoms and lung function in poultry confinement workers in western Canada. Can Respir J. 2003;10(7):375–80. http://www.mendeley.com/catalog/respiratory-symptoms-lung-function-poultry-confinement-workers-western-canada/. Accessed Mar 14 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Chénard L, Senthilselvan A, Grover VK, et al. Lung function and farm size predict healthy worker effect in swine farmers. Chest. 2007;131(1):245–254. doi: 10.1378/chest.05-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duchaine C, Grimard Y, Cormier Y. Influence of building maintenance, environmental factors, and seasons on airborne contaminants of swine confinement buildings. AIHAJ. 2000;61(1):56–63. doi: 10.1202/0002-8894(2000)061<0056:IOBMEF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson BM, Palmberg L, Malmberg PO, Larsson K. Effect of exposure to swine dust on levels of IL-8 in airway lavage fluid. Thorax. 1997;52(7):638–642. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.7.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Malmberg P, Ek A, Larsson K, Palmberg L. Swine dust induces cytokine secretion from human epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115(1):6–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garshick E, Schenker MB, Dosman JA. Occupationally induced airways obstruction. Med Clin N Am. 1996;80(4):851–878. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(05)70470-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charavaryamath C, Singh B. Pulmonary effects of exposure to pig barn air. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2006;1(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsson KA, Eklund AG, Hansson LO, Isaksson BM, Malmberg PO. Swine dust causes intense airways inflammation in healthy subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(4):973–977. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.4.7921472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz DA, Donham KJ, Olenchock SA, et al. Determinants of longitudinal changes in spirometric function among swine confinement operators and farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(1):47–53. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosman JA, Lawson JA, Kirychuk SP, Cormier Y, Biem J, Koehncke N. Three new cases of apparent occupational asthma in swine confinement facility employees. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(6):1281–1282. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00096006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moira CY, Enarson DA, Kennedy SM. The impact of grain dust on respiratory health. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(2 Pt 1):476–487. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pahwa P, Senthilselvan A, McDuffie HH, Dosman JA. Longitudinal decline in lung function measurements among Saskatchewan grain workers. Can Respir J. 2003;10(3):135–141. doi: 10.1155/2003/914753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pahwa P, McDuffie HH, Dosman JA. Longitudinal changes in prevalence of respiratory symptoms among Canadian grain elevator workers. Chest. 2006;129(6):1605–1613. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pahwa P, Senthilselvan A, McDuffie HH, Dosman JA. Longitudinal estimates of pulmonary function decline in grain workers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(3):656–662. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pahwa P, Karunanayake CP, Hagel L, et al. The Saskatchewan rural health study: an application of a population health framework to understand respiratory health outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):400. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canada Health. Stretigies for population health: investing in the health of Canadians. Ottawa. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pahwa P, Karunanayake C, Hagel L, et al. Self-selection bias in an epidemiological study of respiratory health of a rural population. J Agromed. 2012;17(3):316–325. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.686381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickett W, Day L, Hagel L, Brison RJ, Marlenga BL, Pahwa P, Koehncke N, Crowe T, Snodgrass P, Dosman J. The Saskatchewan farm injury cohort: rationale and methodology. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(5):567–575. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J. ATS/ERS task force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pahwa P, Karunanayake CP, Hagel L, Gjevre J, Rennie D, Lawson J, Dosman JA. Prevalence of high epworth sleepiness scale in a rural population. Can Respir J. 2012;19(2):e10–e14. doi: 10.1155/2012/287309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pahwa P, Karunanayake C, Willson PJ, et al. Prevalence of chronic bronchitis in farm and nonfarm rural residents in Saskatchewan. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(12):1481–1490. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182636e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyck R, Karunanayake C, Pahwa P, Hagel L, Lawson J, Rennie D, Dosman J, The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group. Prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidities of diabetes among adults in rural Saskatchewan: the influence of farm residence and agriculture-related exposures. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13:7. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Gjevre JA, Pahwa P, Karunanayake CP, Hagel L, Rennie DC, Lawson J, Dyck R, Dosman JA, The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Team Excessive daytime sleepiness amongst rural residents in Saskatchewan. Can Respir J. 2014;21(4):227–233. doi: 10.1155/2014/921541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janzen B, Karunanayake C, Pahwa P, Dyck R, Rennie D, Lawson J, Pickett W, Bryce R, Hagel L, Zhao G, Dosman J, on behalf of the Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group Exploring diversity in socioeconomic inequalities in health among rural dwelling Canadians. J Rural Health. 2015;31(2):186–198. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karunanayake CP, Rennie DC, Hagel L, Lawson J, Janzen B, Pickett W, Dosman JA, Pahwa P, The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group Access to specialist care in rural Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan rural health study. Healthcare. 2015;3:84–99. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karunanayake CP, Hagel L, Rennie DC, Lawson JA, Dosman JA, Pahwa P, The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group Prevalence and risk factors of respiratory symptoms in rural population. J Agromed. 2015;20(3):310–317. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2015.1042613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rennie DC, Karunanayake CP, Chen Y, Lawson JA, Hagel L, Senthilselvan A, Pahwa P, Dosman JA, The Saskatchewan Rural Cohort Study Group Protective effect of farm residency on asthma and hay fever in women. J Asthma. 2016;53(1):2–10. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1058394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Rennie DC, Karunanayake CP, Janzen B, Hagel L, Pickett W, Dyck R, Lawson J, Dosman JA, Pahwa P, The Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group. Income adequacy and education associated with the prevalence of obesity in rural Saskatchewan. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:700. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/15/700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Sharma M, Lawson JA, Kanthan R, Karunanayake C, Hagel L, Rennie D, Dosman JA, Pahwa P. Factors associated with the prevalence of prostate cancer in rural Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan Rural Health Study. J Rural Health. 2016;32(2):125–135. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rennie DC, Lawson JA, Karunanayake CP, Pahwa P, Chen Y, Chu L, Dosman JA, Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group Farm exposure and atopy in men and women: the Saskatchewan rural health study. J Agromed. 2015;20(3):302–309. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2015.1042612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karunanayake CP, Dosman JA, Hagel L, Rennie DC, Lawson JA, Pahwa P, Saskatchewan Rural Health Study Group. Reference values of pulmonary function tests for rural Canadians. Int J Respir Pulm Med. 2015; 2:021. http://clinmedjournals.org/articles/ijrpm/ijrpm-2-021.pdf.

- 39.Janzen B, Karunanayake C, Rennie D, Pickett W, Lawson J, Kirychuk S, Hagel L, Senthilselvan A, Koehncke N, Dosman J, Pahwa P. Gender differences in the association of individual and contextual exposures with lung function in a rural Canadian population. Lung; 2016. 10.1007/s00408-016-9950-8. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00408-016-9950-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Rai M. Factors contributing to the prevalence of prostate cancer in rural Saskatchewan: the Saskatchewan rural health study. M.Sc thesis, University of Saskatchewan; 2013. https://ecommons.usask.ca/handle/10388/ETD-2013-09-1246. Accessed Nov 23 2016.

- 41.Zhao G. Socioeconomic position, gender and hypertension in a rural Canadian population. MSc Thesis, University of Saskatchewan; 2015. https://ecommons.usask.ca/handle/10388/ETD-2014-12-1852. Accessed Nov 23 2016.

- 42.Pahwa P, Abonyi S, Karunanayake C, Rennie DC, Janzen B, Kirychuk S, Lawson JA, Katapally T, McMullin K, Seeseequasis J, Naytowhow A, Hagel L, Dyck R, Fenton M, Senthilselvan A, Ramsden V, King M, Koehncke N, Marchildon G, McBain L, Smith-Windsor T, Smylie J, Episkenew J, Dosman JA. A community-based participatory research methodology to address, redress, and reassess disparities in respiratory health among First Nations. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:199. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1137-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molenberghs G, Fitzmaurice G, Kenward MG, Tsiatis A, Verbeke G. Handbook of missing data methodology. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Handbooks of Modern Statistical Methods; 2014.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Questionnaire and clinical information collected at the baseline and follow-up surveys. Protocol.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Objectives and major findings of the manuscripts (based on pilot and baseline studies) published in peer-reviewed journals. Objectives and major findings.

Data Availability Statement

Currently the data from the SRHS are not publically available. Anyone interested about the data can contact Dr. James Dosman (james.dosman@usask.ca) or Dr. Punam Pahwa (pup165@mail.usask.ca) for further details.