Abstract

Calcified amorphous tumor (CAT) is a rare, non-neoplastic tumor involving calcium deposition in amorphous materials. Although its etiology is unknown, cases have frequently been reported in patients with hemodialysis for chronic kidney disease. We herein describe a case of cardiac CAT in a 64-year-old woman who had been on hemodialysis for diabetic nephropathy for 20 years, and the findings of the present patient, in association with the findings of previous case reports, suggest that end-stage renal disease seems to play an important role in the onset of CAT, especially in CAT formation at the mitral annulus, which appears to differ from CAT occurring at other sites.

Keywords: calcification, chronic renal failure, cardiac mass

Introduction

Calcified amorphous tumor (CAT) is a pseudoneoplastic intracavitary mass comprising nodular calcium deposition, which was originally described in 1997 (1). CAT is differentiated from other tumors, such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, hamartoma of mature cardiac myocytes, mesothelial monocytic incidental cardiac excrescences, lipomatous hypertrophy of the atrial septum, thrombus and vegetation (2). Although its etiology remains unclear, several cases of CAT involving patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and hemodialysis have been reported (3-7). We herein report a case of a hanging CAT which developed near the mitral valve in a patient on hemodialysis for chronic renal failure due to diabetes mellitus, and we also review previous reports of CAT to evaluate the incidence of ESRD in CAT.

Case Report

A 64-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO). She had been on hemodialysis for diabetic nephropathy for 20 years. She had undergone percutaneous coronary stent implantation into segment 1 of the right coronary artery because of angina pectoris 12 years earlier. She had also undergone surgery for a right femoral neck fracture 15 years earlier and for lumbar spondylosis 14 years earlier. No symptoms were present.

On admission, her body temperature was 36.3℃, blood pressure was 138/62 mmHg, and heart rate was 57 beats/min. Physical examination revealed a systolic murmur (Levine grade II) at the 3rd left sternal border and pulses in the left dorsal pedal and posterior tibial arteries were not palpable.

Laboratory data showed increased serum levels of creatinine (1.96 mg/dL) and intact parathyroid hormone (238.4 pg/mL). Other findings for serum biochemistry were normal, including: calcium, 9.1 mg/dL; phosphate, 2.4 mg/dL; prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), 1.07; activated partial prothrombin time, 30.7 seconds; D-dimer, 1.2 μg/mL, and C-reactive protein, 0.07 mg/dL. Electrocardiography showed a sinus heart rhythm, left axis deviation, Q waves in II, III, aVF, negative T waves in V3-6, and poor R progression in V1-4. Chest radiography demonstrated normal lung fields and a cardiothoracic ratio of 48%.

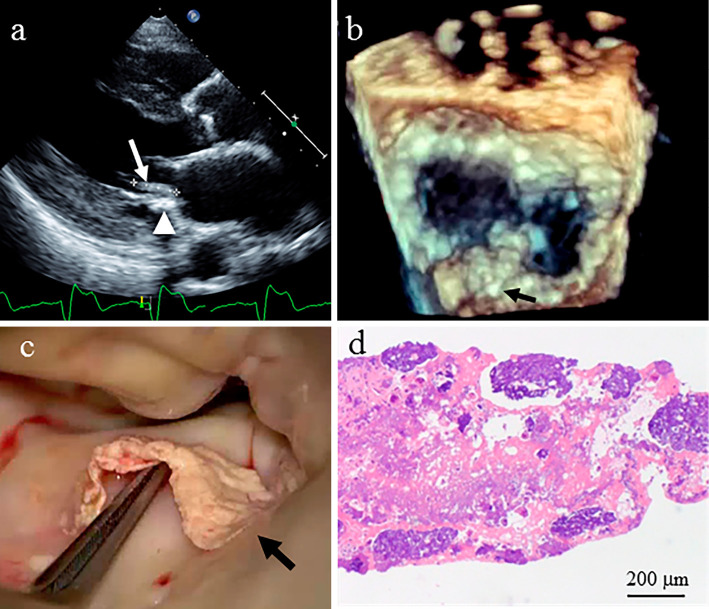

Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography showed a mobile hyperechoic mass measuring 15 mm in length on the posterior leaflet (P2 region) of the mitral valve, with mild mitral regurgitation and marked mitral annular calcification (Figure a and b). Mild aortic stenosis was seen with a calcified aortic valve. However, the mass had not been observed during previous transthoracic echocardiography which had been performed three years before this presentation.

Figure.

a) Transthoracic echocardiography showed a mobile hyperechoic mass measuring 15 mm in length (arrow) on the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve, along with marked mitral annular calcification (arrowhead). b) Three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography shows a mobile hyperechoic mass measuring 15 mm in length on the posterior leaflet (P2 region) of the mitral valve (arrow). c) Intra-operatively, a very thin, calcified mass measuring 15 mm in length is noted on the basal area of the P2 region of the mitral valve. d) A histopathological examination of the specimen reveals focal calcification and the degeneration of fibrin (amorphous materials).

Thrombus and cardiac tumors including calcified amorphous tumor and cardiac myxoma were suspected, because she showed no signs or symptoms of infective endocarditis. Endovascular treatment for ASO was postponed and resection of the mass was performed because of the risk of embolism. Intraoperatively, a very thin calcified mass measuring 15 mm in length on the basal area of the P2 region of the mitral valve was easily removed (Figure c). A histopathological examination of the specimen revealed focal calcification and fibrin degeneration (Figure d). Postoperatively, this patient was discharged without any postoperative complications or problems.

Discussion

The pathologic features of CAT are a nodular calcified mass encapsulated by a rim of dense fibrous connective tissue adherent to the endocardium, the deposition of calcium surrounded by eosinophilic, amorphous material, collagen and chronic inflammatory cells (1). Although the etiology of CAT is uncertain, those pathologic features suggest that CAT involves an organized, calcified mural thrombus (1,8,9) and several factors seem to be linked with CAT, including endothelial damage, stasis, a hypercoagulable state, abnormal calcification metabolism, and chronic inflammation (1,8,10,11). The causes of hypercoagulability include atrial fibrillation, trauma, antiphospholipid syndrome, and malignancy, as well as genetic hematologic diseases, such as protein C and protein S deficiencies (8,12).

The present patient with CAT was receiving hemodialysis for chronic renal failure due to diabetes mellitus. Hemodialysis is also related to hypercoagulability (13), and chronic kidney disease can lead to metabolic bone disease and ectopic calcification, including vascular calcification via the disruption of calcium homeostasis and alterations of the calcium regulatory mechanisms including parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, fibrosis growth factor-23/Klotho, calcium-sensing receptor and Ca2+-phosphate product (14).

We then conducted a literature search for reports of CAT and investigated case backgrounds using the term “calcified amorphous tumor” in PubMed and Igaku Chuo Zasshi, Japan's largest medical-literature database. Fifty-three cases of CAT have been reported (1,3-12,15-38). The total of 54 patients, including our own, showed the following characteristics: mean age, 57±17 years (range, 17-85 years); 22 men, 32 women; 21 Americans, 18 Japanese, 8 non-Japanese Asians (4 Indians, 2 Koreans, one Turkish, one Iranian), and 7 European (2 English, 1 Spanish, 1 Portuguese, 1 Albanian, 1 Belgian, and 1 Greek). Seventeen of those 54 patients had ESRD (16 patients on hemodialysis, 1 patient on peritoneal dialysis), including 13 of 18 Japanese, 1 of 21 Americans, and 3 of 7 Europeans.

The sites of CAT are shown in Table, and CAT was most frequently observed at the mitral annulus, followed by the right ventricle (Table). The data in Table were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test, or the chi-square test. CAT at the mitral annulus was significantly more frequent in patients with ESRD (8/17) than in patients without ESRD (6/37; p=0.0163, chi-square test for independence). On the other hand, CAT presented most frequently at the right atrium and ventricle in non-ERSD patients (Table), and the frequency of CAT in the right ventricle was higher in non-ESRD than in ESRD (p=0.0234, Fisher's exact probability test). ERSD thus appears related to CAT at the annulus of the atrioventricular valve, although the precise mechanisms remain unknown. Moreover, six of eight ESRD patients with CAT at the mitral annulus obviously had mitral annular calcification (MAC). Further study is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the formation of CAT.

Table.

Comparison of Site of Calcified Amorphous Tumor between Patients with and without End-stage Renal Disease.

| CAT sites | All | ESRD | Non ESRD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=54 | n=17 | n=37 | ||

| Age (years) | 57 ± 17 | 60 ± 10 | 55 ± 20 | 0.6861 |

| Sex (male) | 22 | 10 (59%) | 12 (32%) | 0.1172 |

| Mitral annulus | 14 | 8 (47%) | 6 (16%) | 0.0163 |

| Tricuspid annulus | 1 | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.3469 |

| Left atrium | 4 | 2 (12%) | 2 (5%) | 0.3735 |

| Left ventricle | 9 | 3 (18%) | 6 (16%) | 0.5899 |

| Right atrium | 10 | 1 (6%) | 9 (24%) | 0.1029 |

| Right ventricle | 9 | 0 (0%) | 9 (24%) | 0.0234 |

| Aortic valve | 2 | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) | 0.4654 |

| Mitral valve | 4 | 2 (12%) | 2 (5%) | 0.3735 |

| Tricuspid valve | 1 | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0.6852 |

CAT: calcified amorphous tumor, ESRD: end-stage renal disease

Finally, periodic postoperative follow-up with cardiac imaging studies is needed because cardiac CAT may recur and increase in size following surgical excision (39), and even in ERSD patients, CAT should be differentiated from other tumors including lipomatous hamartoma (40).

In conclusion, ESRD seems to play an important role in MAC-related CAT formation, which appears to differ from CAT occurring at other sites.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Reynolds C, Tazelaar HD, Edwards WD. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart (cardiac CAT). Hum Pathol 28: 601-606, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller DV, Tazelaar HD. Cardiovascular pseudoneoplasms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134: 362-368, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morishima A, Sasahashi N, Ueyama K. Calcified amorphous tumors with excision in hemodialysis patients: report of 2 cases. Kyobu Geka 59: 851-854, 2006. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kubota H, Fujioka Y, Yoshino H, et al. Cardiac swinging calcified amorphous tumors in end-stage renal failure patients. Ann Thorac Surg 90: 1692-1694, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawata T, Konishi H, Amano A, Daida H. Wavering calcified amorphous tumour of the heart in a haemodialysis patient. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 16: 219-220, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanaka A, Mizuno M, Suzuki Y, et al. Calcified amorphous tumor in the left atrium in a patient on long-term peritoneal dialysis. Intern Med 54: 481-485, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seo H, Fujii H, Aoyama T, Sasako Y. Cardiac calcified amorphous tumor in a hemodialysis patient. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 24: 461-463, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fealey ME, Edwards WD, Reynolds CA, Pellikka PA, Dearani JA. Recurrent cardiac calcified amorphous tumor: the CAT had a kitten. Cardiovasc Pathol 16: 115-118, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaowalit N, Dearani JA, Edwards WD, Pellikka PA. Calcified right ventricular mass and pulmonary embolism in a previously healthy young woman. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 18: 275-277, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yasui H, Takahama H, Kanzaki H, et al. Time-course changes of cardiac-specific inflammation in a patient with left ventricular calcified amorphous tumor. Circ J 79: 2069-2071, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vlasseros I, Katsi V, Tousoulis D, et al. Visual loss due to cardiac calcified amorphous tumor: a case report and brief review of the literature. Int J Cardiol 152: e56-e57, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hussain N, Rahman N, Rehman A. Calcified amorphous tumors (CATs) of the heart. Cardiovasc Pathol 23: 369-371, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ambühl PM, Wüthrich RP, Korte W, Schmid L, Krapf R. Plasma hypercoagulability in haemodialysis patients: impact of dialysis and anticoagulation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 12: 2355-2364, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tejwani V, Qian Q. Calcium regulation and bone mineral metabolism in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 5: 1913-1936, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewin M, Nazarian S, Marine JE, Yuh DD, Argani P, Halushka MK. Fatal outcome of a calcified amorphous tumor of the heart (cardiac CAT). Cardiovasc Pathol 15: 299-302, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gutiérrez-Barrios A, Muriel-Cueto P, Lancho-Novillo C, Sancho-Jaldón M. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart. Rev Esp Cardiol 61: 892-893, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Habib A, Friedman PA, Cooper LT, Suleiman M, Asirvatham SJ. Cardiac calcified amorphous tumor in a patient presenting for ventricular tachycardia ablation: intracardiac echocardiogram diagnosis and management. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 29: 175-178, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flynn A, Mukherjee G. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 52: 444-446, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vaideeswar P, Karunamurthy A, Patwardhan AM, Hira P, Raut AR. Cardiac calcified amorphous tumor. J Card Surg 25: 32-35, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gupta R, Hote M, Ray R. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart in an adult female: a case report. J Med Case Rep 4: 278, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greaney L, Chaubey S, Pomplun S, St Joseph E, Monaghan M, Wendler O. Calcified amorphous tumour of the heart: presentation of a rare case operated using minimal access cardiac surgery. BMJ Case Rep 2011: (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hyun YK, Cho YH, Lee B, Park HB. Unusual presentation chronic pulmonary embolism due to calcified right ventricular mass. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 19: 91-94, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sousa JS, Tanamati C, Marcial MB, Stolf NA. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart: case report. Rev Bras Cir Cardiovasc 26: 500-503, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishigawa K, Takiuchi H, Kubo Y, Masaki H, Tanemoto K. Calcified amorphous tumor: three-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 20: 355, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fujiwara M, Watanabe H, Iino T, et al. Two cases of calcified amorphous tumor mimicking mitral valve vegetation. Circulation 125: e432-e434, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamamoto M, Nishimori H, Wariishi S, et al. Cardiac calcified amorphous tumor stuck in the aortic valve that mimicked a chameleon's tongue: report of a case. Surg Today 44: 1751-1753, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nazli Y, Colak N, Atar IA, et al. Sudden unilateral vision loss arising from calcified amorphous tumor of the left ventricle. Tex Heart Inst J 40: 453-458, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shikata N, Muroo N, Nakashima H, et al. A case of rapidly progressing calcified amorphous tumor on the mitral valve. J Cardial Jpn Ed 6: 77-80, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi EK, Ro JY, Ayala AG. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart: case report and review of the literature. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 10: 38-40, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mohamedali B, Tatooles A, Zelinger A. Calcified amorphous tumor of the left ventricular outflow tract. Ann Thorac Surg 97: 1053-1055, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sakao T, Ishida N, Kajiwara S, et al. Calcified amorphous tumor of the right atrium after open heart surgery; report of a case. Kyobu Geka 67: 1183-1185, 2014. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Suh JH, Kwon JB, Park K, Park CB. Calcified amorphous tumor in left atrium presenting with cerebral infarction. J Thorac Dis 6: 1311-1314, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rehman A, Heng EE, Cheema FH. Calcified amorphous tumour of right ventricle. Lancet 383: 815, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sabzi F, Karim H, Eizadi B, Faraji R, Javid N. Calcified amorphous tumor of the heart with purple digit. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 6: 261-264, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Prifti E, Kajo E, Krakulli K, Ikonomi M. Surgical excision of a giant calcified amorphous tumour of the right ventricle and right pulmonary artery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 21: 805-807, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kinoshita M, Okayama H, Kawamura G, et al. A calcified amorphous tumor that developed on both sides of the atrioventricular valve annulus. 13: 148-150, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Hemptinne Q, Bar JP, de Cannière D, Unger P. Swinging cardiac calcified amorphous tumour arising from a calcified mitral annulus in a patient with normal renal function. BMJ Case Rep 2015: (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Teoh JK, Steeds RP. Cardiac calcified amorphous tumour. Echo Res Pract 2: I9-I10, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fealey ME, Edwards WD, Reynolds CA, Pellikka PA, Dearani JA. Recurrent cardiac calcific amorphous tumor: the CAT had a kitten. Cardiovasc Pathol 16: 115-118, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Torii Y, Yamada H, Matsukuma S, et al. Left ventricular lipomatous hamartoma mimicking a calcified amorphous tumor. Circulation 133: e408-e410, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]