Abstract

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) regulates diverse cellular responses and is crucial for normal organ development and function. On the other hand, RAS exerts deleterious effects promoting cardiovascular and multiple organ damage and contributes to promoting various aging-related diseases and aging-related decline in multiple organ functions. RAS blockade has been shown to prevent the progression of aging-related phenotypes and promote longevity. Wnt signaling pathway also plays a major role in the regulation of mammalian pathophysiology and is essential for organismal survival, and furthermore, it is substantially involved in the promotion of aging process. In this way, both RAS signaling and Wnt signaling have the functions of antagonistic pleiotropy during the process of growth and aging. Our recent study has demonstrated that an anti-aging effect of RAS blockade is associated with down-regulation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway, providing evidence for the hierarchical relationship between RAS signaling and Wnt signaling in promoting aging-related phenotypes. Here, we review how RAS signaling and Wnt signaling regulate the aging process and promote aging-related diseases.

Keywords: AT1 receptor, ARB, Cardiovascular disease, Complement C1q, Skeletal muscle regeneration

Background

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays pleiotropic roles in regulating mammalian pathophysiology. Angiotensin II (Ang II) is a key molecule of RAS and is produced as a result of sequential cleavage of angiotensinogen by renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Ang II exerts diverse pathophysiological effects on binding to Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor [1]. AT1 receptor is a well-known member of the G protein-coupled receptor family, which shares the structure characterized by seven transmembrane-spanning α-helices. Mice have two AT1 receptor isoforms (AT1a and AT1b) which are encoded by separate genes (Agtr1a and Agtr1b), whereas humans have a single AT1 receptor isoform encoded by AGTR1 gene. Mouse Agtr1a gene is a homolog to human AGTR1 gene, and AT1a receptor is the major AT1 receptor isoform in mice. AT1 receptor is activated by binding of Ang II or by mechanical stretch in the absence of Ang II [2, 3].

A decrease in extracellular volume caused by fluid loss or low salt intake stimulates secretion of renin, which leads to production of Ang II and thereby induces systemic vasoconstriction, salt and water retention, and sympathetic nervous activation. These responses restore blood pressure and electrolyte and water balance. In addition to regulation of hemodynamic homeostasis, RAS is essential for normal organ development. Mice deficient in angiotensinogen [4] or in both AT1a and AT1b receptor isoforms [5, 6] showed abnormal phenotypes in the kidney. The administration of ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers (ARBs) is contraindicated during pregnancy due to an increased risk of fetal disorders [7]. Thus, RAS is crucial for both embryogenesis and maintaining homeostasis and apparently beneficial for survival.

On the other hand, RAS has detrimental effects on cardiovascular tissues. AT1 receptor activation evokes diverse G protein-dependent and G protein-independent signaling pathways, leading to cell proliferation, hypertrophic responses, apoptosis, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and tissue inflammation [8]. RAS has been shown to promote the pathophysiological processes of various aging-related disorders, including not only cardiovascular diseases and heart failure but also diabetes, chronic kidney disease, dementia, osteoporosis, and cancer [9]. Recent studies have demonstrated that inhibition of RAS prolongs the physiological aging process and promotes longevity in rodents [10], suggesting the involvement of RAS in the aging process per se.

In addition to AT1 receptor, Ang II type 2 (AT2) receptor is also a functional receptor with high affinity for Ang II [1]. AT2 receptor activation has vasodilatory, anti-proliferative, and anti-inflammatory effects, which counteract the effects of AT1 receptor signaling [1]. Thus, AT2 receptor signaling may provide cardiovascular protection and possibly prevent the progression of aging-related diseases. Ang II is cleaved by ACE2 to form another peptide Ang (1–7). This ACE2-Ang (1–7) axis, acting via another G protein-coupled receptor Mas, is also involved in vasodilatory, anti-fibrotic, and anti-inflammatory properties [11]. While the ACE-Ang II-AT1 receptor axis has been extensively studied, research on the role of ACE2-Ang (1–7)-Mas receptor axis in the aging process has been limited.

Wnt signaling pathway also regulates diverse cellular responses during embryogenesis and is required for normal development and function of organs [12]. On the other hand, canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is also involved in the aging process and promotes aging-related phenotypes [13, 14]. Accordingly, both RAS and Wnt signaling pathway have antagonistic and pleiotropic effects in the physiological process of growth and aging because they are essential and beneficial early in life but deleterious later in life [9].

We have recently reported that RAS blockade prevented the aging-related functional decline in skeletal muscle and that this anti-aging effect of RAS blockade was associated with down-regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [15]. These findings suggest the relationship between RAS signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in promoting aging-related phenotypes. This review focuses on how RAS and Wnt signaling pathway regulate the aging process and how they play roles as possible targets for preventing and treating aging-related diseases.

RAS in aging-related cardiovascular diseases and heart failure

Aging is usually defined as a progressive loss of multiple organ functions with advancing age. It is regulated by a wide variety of factors including genetic backgrounds and environmental stresses. Aging increases the risks of various cardiovascular diseases, such as hypertension, atherosclerotic vascular disease, cardiac remodeling, and congestive heart failure. RAS is widely recognized as a key factor contributing to the pathogenesis throughout the “cardiovascular continuum” [16].

RAS plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of hypertension even at an early stage. Sustained and excessive activation of RAS signaling induces continuous vasoconstriction and promotes vascular hypertrophy and endothelial dysfunction by direct as well as indirect hemodynamic effects, thereby contributing to the accelerated rise of blood pressure [17]. Indeed, the administration of an ARB reduced the development of hypertension in prehypertensive patients [18]. RAS blockade leads to a better outcome on survival in high-risk animals with hypertension. The treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB doubled the life span of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats to 30 months, which was comparable to that of normotensive rats [19, 20]. This life extension effect was associated with preservation of cardiac function as well as endothelial function by the treatment with an ACE inhibitor or ARB [19, 20].

RAS contributes to the promotion of atherosclerotic process. Ang II stimulates activity of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAD(P)H) oxidase which increased ROS formation [21]. Ang II also stimulates the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promotes the recruitment of macrophages and T cells through the generation of adhesion molecules and chemokines [22]. This increased oxidative stress and proinflammatory state leads to the development of endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling [23]. Furthermore, RAS promotes vasoconstriction, alters the composition of extracellular matrix, and enhances migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [24]. Thus, RAS induces diverse cellular responses within the vascular wall, leading to the progression of atherosclerotic cascade.

Persistent and excessive activation of RAS plays a substantial role in pathological cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac remodeling. AT1 receptor activation induces hypertrophic responses in cardiomyocytes and extracellular matrix protein synthesis in cardiac fibroblasts [25]. Ang II infusion induced cardiac hypertrophy independently of blood pressure elevation in rats [26], and cardiac-specific overexpression of AT1 receptor induced cardiac hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and contractile dysfunction in mice [27, 28]. RAS blockade is highly effective in preventing the progression of cardiac remodeling and heart failure. AT1a receptor-deficient mice showed less severe cardiac dysfunction induced by myocardial infarction [29], administration of cardiotoxic agent doxorubicin [30], or genetic disruption of muscle LIM protein (MLP) [31]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that ARBs were the most effective among antihypertensive drugs for reducing left ventricular mass in patients with essential hypertension [32]. In addition, clinical trials have demonstrated that ACE inhibitors or ARBs reduce death and hospitalization in the broad spectrum of patients with heart failure [33].

RAS in other aging-related diseases

It has been demonstrated that RAS is involved in the pathophysiological processes of other aging-related disorders, such as diabetes, chronic kidney disease, dementia, osteoporosis, and cancer [9].

RAS contributes to the pathogenesis of insulin resistance, a notable feature of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus [34]. Ang II-mediated activation of AT1 receptor modulates the effects of insulin signaling [35]. For example, AT1 receptor activation synergistically promotes the proliferative effects of insulin but inhibits its metabolic actions. Also, the direct effect of Ang II on islet contributes to impaired β cell function. Acute infusion of Ang II inhibited the early phase of insulin secretion in rats [36], and RAS blockade improved islet morphology and prevented islet fibrosis in diabetic rats [37]. Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that RAS blockade improves insulin sensitivity and reduces the incident risk of diabetes in high-risk patients [38].

RAS signaling plays a major role in promoting chronic kidney disease. Ang II induces vasoconstriction of the post-glomerular arterioles and increases the glomerular hydrostatic pressure and the ultrafiltration of plasma proteins, thereby contributing to the onset and progression of chronic renal damage [39]. In addition to hemodynamic effects, Ang II exerts non-hemodynamic effects promoting renal tissue injury, through increased generation of ROS, up-regulation of cytokines and adhesion molecules, activation and recruitment of macrophages, and increased synthesis of extracellular matrix proteins [40]. RAS inhibitors provide renal protection and reduce proteinuria and decline of glomerular filtration rate in patients with chronic kidney disease [41, 42].

Recent studies unraveled the possible involvement of RAS in neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease or bone metabolism. ARB treatment decreased the accumulation of β-amyloid proteins in the brain and attenuated the development of cognitive impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [43]. In ovariectomized rats with hypertension, ARB treatment attenuated osteoporosis and suppressed an increase in osteoclast activity [44]. Clinical studies have suggested that antihypertensive treatment with ACE inhibitors was associated with high bone mineral density and reduced the risk of bone fractures [45].

Furthermore, RAS is associated with cancer-related signaling pathways. AT1 receptor is expressed in several human cancer cell lines including pancreatic and prostate cancer cell lines [46, 47] and in a subpopulation of ER-positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer cases [48], and ARB treatment suppressed AT1 receptor-positive cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth. The growth of tumor cells engrafted in AT1a receptor-deficient mice was reduced, accompanied by reduction in tumor-related angiogenesis [49]. Ang II induced the proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells in the spleen in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma, thereby supplying tumor-associated macrophages to promote tumor development [50]. These findings indicate that RAS signaling plays an important role in tumor growth and progression through inducing tumor cell proliferation, tumor-associated angiogenesis, and tumor-associated macrophage expansion.

RAS in physiological aging process

RAS blockade has been shown to suppress the deleterious effects during the physiological aging process in rodents. The administration of an ACE inhibitor or ARB to CF1 mice or Wistar rats led to a prolongation of life span, which was associated with a decrease in cardiac and renal fibrosis [51, 52]. CF1 mice treated with enalapril, but not with propranolol, nifedipine, or hydrochlorothiazide, revealed protection from organ damage associated with aging and prolonged life span, even though these drugs induced similar hypotensive effects [53]. Therefore, RAS inhibitor regulates life span independently of blood pressure-lowering effect. AT1a receptor-deficient mice also exhibited a prolongation of life span, which was accompanied by less cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [10]. The accumulation of oxidative stress caused by ROS substantially contributes to the aging process [54]. The treatment with an ACE inhibitor was associated with a decrease in apoptosis and the suppression of aging-related decrease in mitochondrial number and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in murine cardiomyocytes [51, 55]. AT1a receptor-deficient mice showed less oxidative damage in the heart and kidney and prevention of aging-related loss of mitochondria in the kidney [10]. In addition, genetic disruption of AT1a receptor induced an increase in expression levels of Nampt and Sirt3 in the kidneys of aging mice [10]. In a nutrient-deprived environment, increased expression of Nampt leads to the accumulation of its biosynthetic product nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) in mitochondria, which in turn activates mitochondrial sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) [56]. SIRT3 is a NAD+-dependent deacetylase that protects against stress-mediated cell death. These findings demonstrate that inhibition of RAS promotes longevity, possibly through attenuation of oxidative stress and up-regulation of prosurvival genes.

We have recently reported that AT1a receptor-deficient mice showed less severe aging-related phenotypes in other tissues as well, such as functional decline in skeletal muscle [15]. RAS blockade can prevent aging-related sarcopenia. It has been demonstrated that elderly persons with hypertension taking ACE inhibitors had lower decline in muscle strength and larger muscle mass of the lower extremities than users of other antihypertensive drugs [57, 58]. In aged mice, ARB treatment protected against disuse atrophy of skeletal muscle [59]. One of the hallmarks of aging is a decline in the regenerative capacity of skeletal muscle following injury. ARB treatment led to histological improvement in skeletal muscle regeneration after laceration in mice [60]. ARB inhibited transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling and thereby attenuated TGF-β-mediated impairment of muscle regeneration in mice with myopathy [61]. In addition, Ang II may have direct anti-proliferative effects on satellite cells, which are crucial for skeletal muscle growth and regeneration, via AT1 receptor [62]. We have shown that treatment with an ARB restored skeletal muscle function assessed by treadmill test after cryoinjury in mice [15]. ARB-treated mice showed an increase in satellite cell population, enhanced regeneration of myofibers, and decreased fibrosis in cryoinjured skeletal muscle. Taken together, RAS can be targeted to protect against deleterious effects associated with aging process and promote longevity.

Relationship between RAS and Wnt signaling in aging

Wnt proteins initiate signaling cascade on binding to Frizzled receptor and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) 5/6 coreceptor, which leads to stabilization of cytosolic β-catenin [12, 63]. Then, translocating to nucleus, β-catenin activates target gene transcription. It has been demonstrated that canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is also involved in the aging process. Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity was enhanced in multiple tissues of a klotho-deficient mouse model of accelerated aging [64]. Wnt treatment attenuated skeletal muscle regeneration in young mice, and inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling restored the impairment of muscle regeneration in aged mice [13]. Moreover, Wnt/β-catenin signaling was augmented in skeletal muscle satellite cells exposed to the serum of aged mice, indicating that components of aged serum contributed to the aging-related activation of Wnt signaling [13]. Complement C1q has recently been identified as an activator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling independently of Wnt [14]. C1q activates canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling through binding to Frizzled receptor and inducing C1s-dependent cleavage of LRP6 coreceptor. Macrophages are major cells that secrete C1q [65]. Aging mice have increased serum and tissue levels of C1q and enhanced Wnt signaling activity [14]. C1q treatment stimulated fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis but suppressed satellite cell proliferation in skeletal muscle, and promoted aging-related impairment of skeletal muscle regeneration through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [14]. C1q was secreted from macrophages recruited to the aorta in Ang II-infused mice, and C1q-mediated activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling induced proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and promoted arterial remodeling [66].

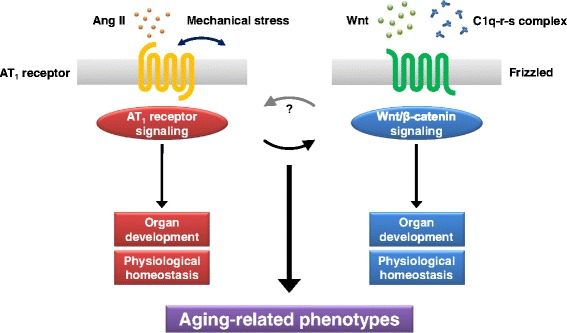

We have demonstrated that serum C1q concentration was increased, and C1q expression and Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity in skeletal muscle were augmented after cryoinjury in mice, but ARB treatment inhibited both the increase in serum C1q level and the activation of C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling in injured muscle [15]. C1q expression in macrophages was reduced by administration of ARB both in culture and in injured muscle. Moreover, these beneficial effects of ARB on skeletal muscle repair after injury were reversed by topical administration of C1q [15]. These findings suggest that RAS blockade prevents aging-related phenotypes through down-regulation of aging-promoting C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and that RAS signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are hierarchically related in promoting the aging process (Fig. 1). We propose that RAS blockade reduces systemic and local levels of C1q through inhibiting C1q synthesis in infiltrated macrophages and thereby enhances proliferation and differentiation of satellite cells, leading to promotion of skeletal muscle repair. Besides selectively inhibiting Ang II-induced activation of AT1 receptor, ARB may enhance Ang II-induced activation of AT2 receptor [67]. Further studies will be required to elucidate whether AT2 receptor activation contributes to down-regulation of C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling and protection against aging.

Fig. 1.

RAS signaling and Wnt signaling in aging process. AT1 receptor is activated upon stimulation by binding of Ang II or mechanical stress, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade is initiated by binding of Wnt proteins or C1q-r-s complex to Frizzled receptor. Both AT1 receptor signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are essential for normal organ development and crucial for regulation of physiological homeostasis. On the other hand, AT1 receptor signaling and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are involved in the aging process, and they are hierarchically related in promoting aging-related phenotypes. AT1 receptor blockade protects against aging-related deleterious effects through down-regulation of aging-promoting C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

Conclusions

RAS is profoundly involved in the progression of various aging-related diseases and the promotion of the aging process. RAS blockade has been shown to protect against aging-related deleterious effects and promote longevity. We have recently shown that this anti-aging effect of RAS blockade was mediated by down-regulation of aging-promoting C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, suggesting the hierarchical relationship between RAS signaling and Wnt signaling in promoting aging-related phenotypes. It is a matter of interest whether blocking RAS signaling or C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling could prevent geriatric frailty and prolong life span in humans. It remains to be elucidated how RAS signaling induces C1q expression in macrophages during the aging process. Further investigations of the relationship between RAS signaling and C1q-Wnt/β-catenin signaling will provide insights into the mechanisms responsible for aging-related functional decline of multiple organs and open up a path toward the development of novel therapeutics against aging-related diseases.

Abbreviations

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; Ang, angiotensin; ARB, angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker; AT1, angiotensin II type 1; LRP, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein; MLP, muscle LIM protein; NAD(P)H, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SIRT, sirtuin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI 26670395 to HA and AMED-CREST, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development to HA and IK) and Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (to HA and IK).

Authors’ contributions

TK and HA wrote the manuscript, and JS and IK helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

HA has received trust research/joint research funding from Shionogi & Co., Ltd., and research funding from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. JS has received research funding from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd. IK has received research funding from Astellas Pharma Inc., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and has affiliations with endowed department sponsored by Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Akazawa H, Yano M, Yabumoto C, Kudo-Sakamoto Y, Komuro I. Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor-induced cell signaling. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19:2988–95. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou Y, Akazawa H, Qin Y, Sano M, Takano H, Minamino T, et al. Mechanical stress activates angiotensin II type 1 receptor without the involvement of angiotensin II. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:499–506. doi: 10.1038/ncb1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasuda N, Miura S, Akazawa H, Tanaka T, Qin Y, Kiya Y, et al. Conformational switch of angiotensin II type 1 receptor underlying mechanical stress-induced activation. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:179–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niimura F, Labosky PA, Kakuchi J, Okubo S, Yoshida H, Oikawa T, et al. Gene targeting in mice reveals a requirement for angiotensin in the development and maintenance of kidney morphology and growth factor regulation. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2947–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI118366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliverio MI, Kim HS, Ito M, Le T, Audoly L, Best CF, et al. Reduced growth, abnormal kidney structure, and type 2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor-mediated blood pressure regulation in mice lacking both AT1A and AT1B receptors for angiotensin II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchida S, Matsusaka T, Chen X, Okubo S, Niimura F, Nishimura H, et al. Murine double nullizygotes of the angiotensin type 1A and 1B receptor genes duplicate severe abnormal phenotypes of angiotensinogen nullizygotes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:755–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper WO, Hernandez-Diaz S, Arbogast PG, Dudley JA, Dyer S, Gideon PS, et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2443–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunyady L, Catt KJ. Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:953–70. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamo T, Akazawa H, Komuro I. Pleiotropic effects of angiotensin II receptor signaling in cardiovascular homeostasis and aging. Int Heart J. 2015;56:249–54. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benigni A, Corna D, Zoja C, Sonzogni A, Latini R, Salio M, et al. Disruption of the Ang II type 1 receptor promotes longevity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:524–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI36703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang F, Yang J, Zhang Y, Dong M, Wang S, Zhang Q, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin 1-7: novel therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:413–26. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, Lee M, Kuo CJ, Keller C, et al. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science. 2007;317:807–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1144090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naito AT, Sumida T, Nomura S, Liu ML, Higo T, Nakagawa A, et al. Complement C1q activates canonical Wnt signaling and promotes aging-related phenotypes. Cell. 2012;149:1298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabumoto C, Akazawa H, Yamamoto R, Yano M, Kudo-Sakamoto Y, Sumida T, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockade promotes repair of skeletal muscle through down-regulation of aging-promoting C1q expression. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14453. doi: 10.1038/srep14453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzau V. The cardiovascular continuum and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade. J Hypertens Suppl. 2005;23:S9–17. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000165623.72310.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folkow B. Physiological aspects of primary hypertension. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:347–504. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julius S, Nesbitt SD, Egan BM, Weber MA, Michelson EL, Kaciroti N, et al. Feasibility of treating prehypertension with an angiotensin-receptor blocker. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1685–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linz W, Jessen T, Becker RH, Schölkens BA, Wiemer G. Long-term ACE inhibition doubles lifespan of hypertensive rats. Circulation. 1997;96:3164–72. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.9.3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linz W, Heitsch H, Schölkens BA, Wiemer G. Long-term angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade with fonsartan doubles lifespan of hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:908–13. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.4.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrido AM, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases and angiotensin II receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrario CM, Strawn WB. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and proinflammatory mediators in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koh KK, Oh PC, Quon MJ. Does reversal of oxidative stress and inflammation provide vascular protection? Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81:649–59. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmieder RE, Hilgers KF, Schlaich MP, Schmidt BM. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet. 2007;369:1208–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Iwao H. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dostal DE, Baker KM. Angiotensin II stimulation of left ventricular hypertrophy in adult rat heart. Mediation by the AT1 receptor. Am J Hypertens. 1992;5:276–80. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.5.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hein L, Stevens ME, Barsh GS, Pratt RE, Kobilka BK, Dzau VJ. Overexpression of angiotensin AT1 receptor transgene in the mouse myocardium produces a lethal phenotype associated with myocyte hyperplasia and heart block. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paradis P, Dali-Youcef N, Paradis FW, Thibault G, Nemer M. Overexpression of angiotensin II type I receptor in cardiomyocytes induces cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harada K, Sugaya T, Murakami K, Yazaki Y, Komuro I. Angiotensin II type 1A receptor knockout mice display less left ventricular remodeling and improved survival after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999;100:2093–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.20.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toko H, Oka T, Zou Y, Sakamoto M, Mizukami M, Sano M, et al. Angiotensin II type 1a receptor mediates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:597–603. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto R, Akazawa H, Ito K, Toko H, Sano M, Yasuda N, et al. Angiotensin II type 1a receptor signals are involved in the progression of heart failure in MLP-deficient mice. Circ J. 2007;71:1958–64. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klingbeil AU, Schneider M, Martus P, Messerli FH, Schmieder RE. A meta-analysis of the effects of treatment on left ventricular mass in essential hypertension. Am J Med. 2003;115:41–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00158-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mielniczuk L, Stevenson LW. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type I receptor blockers in the management of congestive heart failure patients: what have we learned from recent clinical trials? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2005;20:250–5. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000167721.22453.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad A, Quyyumi AA. Renin-angiotensin system and angiotensin receptor blockers in the metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2004;110:1507–12. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141736.76561.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velloso LA, Folli F, Sun XJ, White MF, Saad MJ, Kahn CR. Cross-talk between the insulin and angiotensin signaling systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12490–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlsson PO, Berne C, Jansson L. Angiotensin II and the endocrine pancreas: effects on islet blood flow and insulin secretion in rats. Diabetologia. 1998;41:127–33. doi: 10.1007/s001250050880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tikellis C, Wookey PJ, Candido R, Andrikopoulos S, Thomas MC, Cooper ME. Improved islet morphology after blockade of the renin-angiotensin system in the ZDF rat. Diabetes. 2004;53:989–97. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, O’Keefe JH., Jr Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:821–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Remuzzi G, Bertani T. Pathophysiology of progressive nephropathies. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1448–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Remuzzi G, Perico N, Macia M, Ruggenenti P. The role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;68:S57–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Ho L, Chen L, Zhao Z, Zhao W, Qian X, et al. Valsartan lowers brain β-amyloid protein levels and improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3393–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimizu H, Nakagami H, Osako MK, Hanayama R, Kunugiza Y, Kizawa T, et al. Angiotensin II accelerates osteoporosis by activating osteoclasts. FASEB J. 2008;22:2465–75. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-098954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Treatment with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and calcium-channel blockers is associated with a reduced fracture risk: a nationwide case-control study. J Hypertens. 2006;24:581–9. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000203845.26690.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujimoto Y, Sasaki T, Tsuchida A, Chayama K. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression in human pancreatic cancer and growth inhibition by angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:197–200. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uemura H, Ishiguro H, Nakaigawa N, Nagashima Y, Miyoshi Y, Fujinami K, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blocker shows antiproliferative activity in prostate cancer cells: a possibility of tyrosine kinase inhibitor of growth factor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhodes DR, Ateeq B, Cao Q, Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Laxman B, et al. AGTR1 overexpression defines a subset of breast cancer and confers sensitivity to losartan, an AGTR1 antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:10284–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900351106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Egami K, Murohara T, Shimada T, Sasaki K, Shintani S, Sugaya T, et al. Role of host angiotensin II type 1 receptor in tumor angiogenesis and growth. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:67–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI16645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cortez-Retamozo V, Etzrodt M, Newton A, Ryan R, Pucci F, Sio SW, et al. Angiotensin II drives the production of tumor-promoting macrophages. Immunity. 2013;38:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferder L, Inserra F, Romano L, Ercole L, Pszenny V. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on mitochondrial number in the aging mouse. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C15–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basso N, Cini R, Pietrelli A, Ferder L, Terragno NA, Inserra F. Protective effect of long-term angiotensin II inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1351–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00393.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferder LF, Inserra F, Basso N. Advances in our understanding of aging: role of the renin-angiotensin system. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:189–94. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00139-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–47. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferder L, Romano LA, Ercole LB, Stella I, Inserra F. Biomolecular changes in the aging myocardium: the effect of enalapril. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:1297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang H, Yang T, Baur JA, Perez E, Matsui T, Carmona JJ, et al. Nutrient-sensitive mitochondrial NAD+ levels dictate cell survival. Cell. 2007;130:1095–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Onder G, Penninx BW, Balkrishnan R, Fried LP, Chaves PH, Williamson J, et al. Relation between use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and muscle strength and physical function in older women: an observational study. Lancet. 2002;359:926–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Di Bari M, van de Poll-Franse LV, Onder G, Kritchevsky SB, Newman A, Harris TB, et al. Antihypertensive medications and differences in muscle mass in older persons: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:961–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burks TN, Andres-Mateos E, Marx R, Mejias R, Van Erp C, Simmers JL, et al. Losartan restores skeletal muscle remodeling and protects against disuse atrophy in sarcopenia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:82ra37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bedair HS, Karthikeyan T, Quintero A, Li Y, Huard J. Angiotensin II receptor blockade administered after injury improves muscle regeneration and decreases fibrosis in normal skeletal muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:1548–54. doi: 10.1177/0363546508315470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohn RD, van Erp C, Habashi JP, Soleimani AA, Klein EC, Lisi MT, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-β-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat Med. 2007;13:204–10. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshida T, Galvez S, Tiwari S, Rezk BM, Semprun-Prieto L, Higashi Y, et al. Angiotensin II inhibits satellite cell proliferation and prevents skeletal muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23823–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.449074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;317:803–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petry F, Botto M, Holtappels R, Walport MJ, Loos M. Reconstitution of the complement function in C1q-deficient (C1qa-/-) mice with wild-type bone marrow cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4033–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sumida T, Naito AT, Nomura S, Nakagawa A, Higo T, Hashimoto A, et al. Complement C1q-induced activation of β-catenin signalling causes hypertensive arterial remodelling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu L, Iwai M, Nakagami H, Li Z, Chen R, Suzuki J, et al. Roles of angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation associated with selective angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade with valsartan in the improvement of inflammation-induced vascular injury. Circulation. 2001;104:2716–21. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]