Abstract

Background

Two large-scale prostate cancer screening trials with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) have given conflicting results in terms of the efficacy of such screening. One of those trials, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial, previously reported outcomes through 13 years of follow-up. Here we present updated findings from PLCO.

Methods

PLCO randomized subjects from 1993–2001 to an intervention or control arm. Intervention arm men received annual PSA tests for six years and digital rectal exam for four years. We used linkage with the National Death Index (NDI) to extend mortality follow-up to a maximum of 19 years from randomization.

Results

38,340 and 38,343 men were randomized to the intervention and control arms, respectively. Median (25th/75th) follow-up time was 14.8 years (12.7/16.5) in the intervention and 14.7 years (12.6/16.4) in the control arm. 255 (intervention arm) versus 244 (control arm) deaths from prostate cancer were observed, for a rate-ratio (RR) of 1.04 (95% CI: 0.87–1.24). The RR for all-cause mortality was 0.977 (95% CI: 0.950,1.004). An estimated 86% of control versus 99% of intervention arm men received any PSA testing during the trial, with estimated yearly screening phase PSA testing rates of 46% (control) versus 84% (intervention).

Conclusion

Extended follow-up of PLCO over a median of 15 years continues to indicate no reduction in prostate cancer mortality for the intervention compared to control arms. Due to the high rate of control arm PSA testing, this finding can be viewed as showing no benefit of organized over opportunistic screening.

Keywords: digital rectal exam (DRE) prostate cancer, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), randomized trial, screening

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in U.S. men1. In addition to improvements in treatment and efforts at primary prevention of prostate cancer, another potential tool to reduce the burden of prostate cancer mortality is early detection. Although screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) had been ongoing for over 25 years, it is still not clear whether such screening reduces prostate cancer mortality, and if so, whether the benefits outweigh the established harms2,3. Due to its frequently indolent nature, and the difficulty in distinguishing indolent from potentially fatal prostate cancer, the harms of prostate cancer screening in the form of overdiagnosed and overtreated cases are considerable, as are the financial and medical resource costs. As such, prostate cancer screening has a high bar in terms of the magnitude of mortality reduction required to make screening worthwhile.

This uncertainty about the utility of prostate cancer screening persists even as two large-scale randomized trials of prostate cancer screening have reported their findings. The most recent analysis reported from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), with follow-up through 13 years, showed a prostate cancer mortality rate ratio (RR) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.69–0.91); a prior analysis through a median of 11 years follow-up showed similar findings (RR=0.79, 95% CI: 0.68–0.91)4,5. In contrast, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial did not show any difference between screening and usual care; through up to 13 years of follow-up the prostate cancer mortality RR was 1.09 (95% CI: 0.87–1.36)6.

The conflicting results of the trials, and the fact that, even accepting the rate ratio reported from the ERSPC, it is not clear whether the harms of screening outweigh the benefits, led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to give prostate cancer screening a D recommendation, i.e., recommend against screening, for the general U.S. population3.

In the current analysis, we update the mortality results of the PLCO trial, with follow-up extended to up to 19 years from randomization. In addition to providing a more stable estimate of the risk ratio based on more prostate cancer deaths, this updated analysis will also allow for examination of the longer-term effects of prostate cancer screening, which is especially relevant given the natural history of the disease.

Methods

The design and methods of the PLCO Trial have been described6,7. Briefly, randomization at ten U.S. screening centers of subjects age 55–74 to either an intervention or control arm occurred from 1993–2001. The primary exclusion criteria were a history of a PLCO cancer, current cancer treatment, and beginning in 1995, having had more than one PSA blood test in the prior three years. At study entry, participants completed a self-administered baseline questionnaire that included demographics, general risk factors, and screening and medical histories.

Screening Examinations

Men in the intervention arm received a PSA blood test and DRE at baseline (T0), an annual DRE for three more years (T1–T3) and, generally, an annual PSA for five more years (T1–T5). Men randomized prior to May, 1994, only received PSA for T1–T3 and those randomized from June 1994 to May 1995 received PSA only at T1–T3 and T5. Participants also received chest radiographs annually for four years and flexible sigmoidoscopy at baseline and year three or five. PSA results were classified as abnormal if they were greater than 4 ng/m. DRE results were considered abnormal if there was nodularity or induration of the prostate, or if the examiner judged other criteria to be suspicious for cancer, including asymmetry.

Participants and their physicians were notified in writing of any suspicious abnormality on screening. The diagnostic process following a positive screen was managed by participants’ primary care physicians, and was not dictated by the trial.

Ascertainment of Study End-points

The primary trial endpoint for the prostate component of PLCO was prostate cancer-specific mortality; secondary endpoints included prostate cancer incidence, cancer stage and Gleason grade, survival, harms of screening, contamination and compliance, and all-cause mortality.

The original analysis period for the PLCO prostate component was from randomization through 13 years of follow-up or December 31st, 2009, whichever came first6. Trial endpoints for this period have been described in previous publications. For this original period, incident cancers and deaths were primarily ascertained through a mailed annual study update questionnaire (ASU). Incident cancers reported on the ASU were verified by obtaining medical records and utilizing a standardized abstracting process. Next of kin notified the trial of deaths, which were verified by obtaining death certificates; National Death Index (NDI) searches were also used. The underlying cause of death was determined in a uniform and unbiased manner from medical records and the death certificate using a blinded endpoint verification process conducted by an independent death review committee8.

As has been previously described, going forward from the original analysis period, a structural change in the operation of PLCO affected the way cancer incidence and mortality endpoints were ascertained9. Briefly, beginning in mid-2011, PLCO subjects were re-consented with 3 possible options: active follow-up through a central coordinating center, passive follow-up implemented at the screening centers, and refusal of further follow-up. Active participants were eligible for linkages to NDI and state cancer registries and also could be contacted directly to fill out questionnaires or for future specimen collections. Passive participants did not have their personally identifiable information (PII) transferred to the central coordinating center but could still be passively followed through NDI and state cancer registries by their local screening centers; those deceased at the time of re-consent were considered passive participants. Finally, refusers had no further active or passive follow-up.

All active and passive subjects were linked to the NDI, with complete death information through the end of 2012. For these subjects, the end-of-follow-up for mortality for this analysis was December 31st, 2012 or date of death, whichever came first. For refusers, because they had to actively refuse and thus were known to be alive at their refusal date (which ranged from mid-2011 until mid-2012 at nine centers and 2014 at one center), their end of follow-up was their refusal date or December 31, 2012, whichever came first.

For the extended analysis, the trial ascertained deaths primarily through the NDI, so medical records were not available to perform endpoint verification. Therefore, for deaths occurring after the original cutoff (Dec 31st, 2009), the underlying cause of death from the NDI was used to determine whether deaths were from prostate cancer or not; for deaths before that date, the endpoint-verified classifications used in the original report were also used here. Alternative analyses were performed to assess the effect of using only death certificate (or NDI) information instead of the endpoint-verified classifications for the originally reported deaths. In computing all-cause mortality, deaths from lung and colorectal cancer were excluded because trial participants were screened for those cancers and extended mortality follow-up for them is ongoing.

Only mortality outcomes are reported on here. Linkage with cancer registries to ascertain incident prostate cancers is ongoing, so complete incidence data for the period after Dec31st, 2009 are not currently available. For those prostate cancers reported from the original analysis period, 4250 in the intervention and 3815 in the control arm, we computed the proportion of total prostate cancer deaths in the extended analysis that derived from these cases6.

A secondary trial endpoint was assessing non-protocol use of PLCO screening tests. Use of PSA testing outside of the trial protocol was assessed through periodic surveys of a sample of trial participants. Surveys were performed for study years 0–5 in the control arm only and study years 6–17 in both arms. The survey consisted of a self-administered health status questionnaire (HSQ) that inquired about the use of various preventative health procedures, including the PLCO screening tests. For the control arm, the survey asked whether the respondent ever had the test in question, and if so, when the most recent test was (within the past year, 1–2 years ago, 2–3 years ago, more than 3 years ago), and the reason for the most recent test (“because of a specific health problem”, “follow-up of a previous health problem” and “as part of a routine health check-up”). For the intervention arm, the survey asked whether the respondent ever had the test in question since the date of their last PLCO screen with that test, with the follow-up questions (timing and reason) referring only to tests after that date. The surveys were customized so that a subject’s actual last PLCO screening dates were pre-written on the form; if they had no PLCO screens then the phrase “since their last PLCO screen” was omitted.

Statistical Methods

Mortality rates from prostate cancer were defined as deaths from prostate cancer during the follow-up period divided by the person years (PY) of follow-up. The rate-ratio (RR) of the intervention to control arm was computed as the ratio of the rates in the two arms. The 95% confidence interval for the RR was calculated assuming a Poisson distribution of events and using the profile likelihood method; p-values were computed based on the normal approximation to the Poisson10. We also utilized Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for prostate cancer death associated with being randomized to the intervention as compared to control arm; subjects not known to have died of prostate cancer were censored at the end of their follow-up11.

For various study periods, we computed HSQ survey rates for having PSA tests in the past year for screening, PSA tests in the past year for any reason, PSA tests in the past 3 years for any reason and PSA tests ever for any reason. Note it was not possible to estimate the proportion ever receiving a PSA test for screening because the reason for testing question only related to subjects’ most recent test. For the intervention arm, since the survey questions only referred to tests taken after the last PLCO protocol test, the computed rates were adjusted to account for PLCO protocol PSA tests taken within the relevant time period (for PSA tests in the past 3 years) or at any time (for PSA tests ever). Also, as noted previously, for the screening period the survey excluded so-called “baseline contaminated subjects”, i.e., those who responded on the baseline questionnaire as having received 2 or more PSA tests in the prior 3 years. These were previously assumed, in calculating contamination rates, to have had screening PSA tests every year during the screening phase. A similar adjustment was performed here, so the displayed rate reflects a weighted average of the survey rates for those without baseline contamination (90%) and the assumed rates for those with baseline contamination.

Results

A total of 38,340 and 38,343 men were randomized to the intervention and control arms, respectively. The demographics and medical history of subjects were similar across arms (Table 1). A total of 88.5% were non-Hispanic white and 35% were age 65 or over at randomization.

Table 1.

Demographics of PLCO population

| Intervention (N=38340) | Control (N=38343) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55–59 | 12387 (32.3) | 12372 (32.3) |

| 60–64 | 12012 (31.3) | 12015 (31.3) | |

| 65–69 | 8877 (23.2) | 8885 (23.2) | |

| 70–74 | 5064 (13.2) | 5071 (13.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 33043 (86.2) | 32136 (83.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1713 (4.5) | 1657 (4.3) | |

| Hispanic | 816 (2.1) | 787 (2.1) | |

| Asian | 1532 (4.0) | 1477 (3.9) | |

| Am Indian/Alaska Native | 92 (0.2) | 96 (0.3) | |

| Education | < High School | 3101 (8.3) | 2994 (8.3) |

| High School | 11347 (30.4) | 11185 (30.9) | |

| Some College | 7643 (20.4) | 7424 (20.5) | |

| College Graduate | 7037 (18.8) | 6876 (19.0) | |

| Post-graduate Study | 8257 (22.1) | 7780 (21.5) | |

| Family history of prostate cancer | 2737 (7.5) | 2589 (7.3) | |

| PSA test within the past 3 years | Once | 13252 (38.8) | 13135 (39.5) |

| More than once | 3588 (10.5) | 3760 (11.3) |

Note: Percentages exclude unknowns except for age.

With respect to transfer status to centralized follow-up, the proportion of refusers was 8.4% in the intervention versus 11.3% in the usual care arm (p <0.001). Median follow-up time was similar for refusers (14.9 years intervention and 14.8 years control) and active/passive participants (median 14.8 years intervention and 14.7 years usual care); note that by definition refusers had to survive at least until the transition time to centralized follow-up whereas passive participants could have died earlier. Overall, follow-up time was a median (25th/75th) of 14.8 years (12.7/16.5) in the intervention arm versus 14.7 years (12.6/16.4) in the control arm. The maximum follow-up was 19.1 years in each arm.

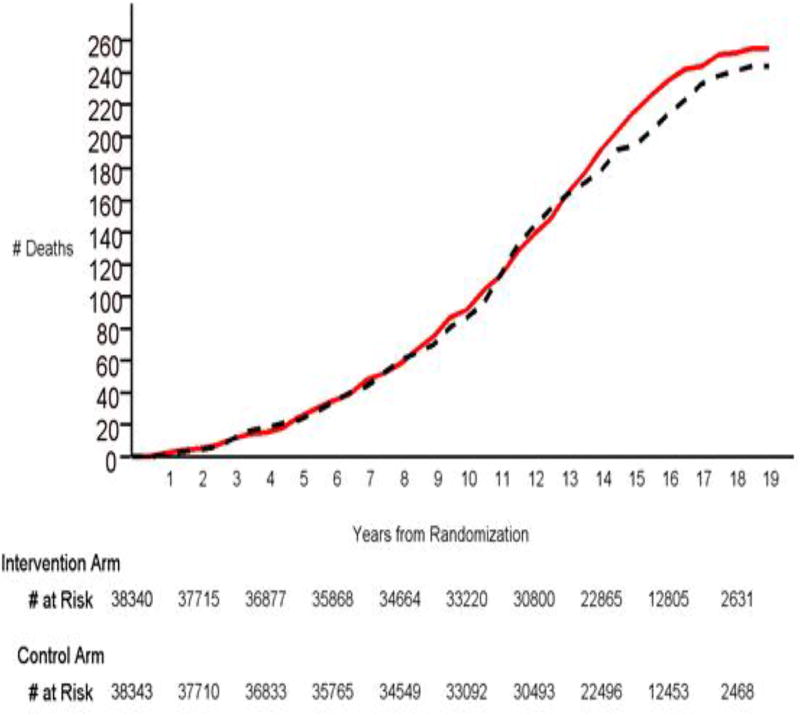

Prostate cancer deaths by arm are shown in Table 2. A total of 255 prostate cancer deaths (rate 47.8 per 100,000 PY) were observed in the intervention versus 244 (rate 46.0 per 100,000 PY) in the control arm. The rate ratio (RR) was 1.04 in favor of the control arm (95% CI: 0.87–1.24). Proportional hazards modeling shows that the HR was essentially identical to the RR, with similar confidence interval and p-value (Table 2). Figure 1 displays cumulative prostate cancer deaths by study time. RRs and HRs varied little by cumulative study time period. RRs were 1.07 (95% CI: 0.78–1.48), 0.99 (95% CI: 0.77–1.29) and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.81–1.25) for study periods 0–8 years, 0–10 years, and 0–12 years, respectively; HRs were similar (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prostate cancer and all-cause mortality by arm

| Intervention | Control | Rate Ratio (95% CI) [p-value] |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) [p-value] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person Years | 533014 | 529860 | |||

| Cause of death | Time Period | Number Deaths (rate per 105 PY) | Number Deaths (rate per 105 PY) | ||

| Prostate Cancer | All | 255 (47.8) | 244 (46.0) | 1.04 (0.87–1.24) [0.67] | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) [0.72] |

| Years 0–8 | 75 (22.8) | 70 (21.3) | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) [0.68] | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) [0.69] | |

| Years 0–10 | 113 (28.6) | 114 (28.9) | 0.99 (0.77–1.29) [0.93] | 0.99 (0.76–1.28) [0.99] | |

| Years 0–12 | 165 (36.2) | 164 (36.1) | 1.003 (0.81–1.25) [0.98] | 1.001 (0.80–1.25) [0.99] | |

| All-cause* | All | 9212 (1728.3) | 9375 (1769.3) | 0.977 (0.950,1.004) [0.11] | 0.973 (0.945– 1.001) [0.06] |

- Excluding colorectal cancer and lung cancer

Figure 1.

Deaths from prostate cancer by arm and years from randomization. Red solid line is intervention arm, black dotted line is control arm. Numbers still at risk at selected time points are listed below the graph.

For the newly determined deaths (occurring after December 31, 2009), endpoint verification was not performed due to lack of medical records collected. We examined the potential impact of this by re-performing the analysis using only death certificate or NDI underlying cause data for all deaths. The RR increased slightly to 1.06 (95% CI: 0.89–1.26) and the HR increased slightly to 1.05 in favor of the control arm (95% CI:0.88 – 1.26).

The previously reported analysis of cases occurring through the end of 2009 and within 13 years of randomization, for which median follow-up for the cohort was 11.9 years, showed a total of 4250 intervention and 3815 control arm prostate cancer cases. Of these, 2539 (60%) intervention arm and 1996 (52%) control arm cases were diagnosed during the screening phase (first 6 trial years); the incidence RR during the screening phase was 1.27 (95% CI: 1.20–1.35). Of the currently reported 255 intervention arm prostate cancer deaths, 88.6% came from these previously reported 4250 cases and 61.6% came from the 2539 screening phase cases. Comparable figures for the control arm (244 currently reported prostate cancer deaths) were 88.9% and 58.6%.

All-cause mortality rates were 1728 and 1769 (per 100,000 PY) in the intervention and control arms, respectively (Table 2). The HR was 0.973 (95% CI: 0.945–1.001), which was borderline statistically significant in favor of the intervention arm (p=0.06); the RR was similar (RR=0.977; 95% CI: 0.950–1.004), although the p-value was slightly higher (p=0.11). Table 3 shows the distribution of all-cause mortality. The proportions from the various causes of deaths were generally similar across arms.

Table 3.

Causes of death by arm

| Intervention | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Cause of Death | N(%) | N(%) |

| Prostate Cancer | 255 (2.8) | 244 (2.6) |

| Other Cancer (excluding lung & colorectal cancer) | 1933 (21.0) | 1882 (20.1) |

| Ischemic Heart Disease | 1699 (18.4) | 1650 (17.6) |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 454 (4.9) | 513 (5.5) |

| Other Circulatory Disease | 1317 (14.3) | 1364 (14.6) |

| Respiratory Disease | 1028 (11.2) | 1069 (11.4) |

| Digestive Disease | 302 (3.3) | 303 (3.2) |

| Infectious Disease | 187 (2.0) | 175 (1.9) |

| Endocrine & Metabolic | 334 (3.6) | 371 (4.0) |

| Nervous System | 438 (4.8) | 470 (5.0) |

| Accidental | 463 (5.0) | 482 (5.1) |

| Other | 802 (8.7) | 852 (9.1) |

| Total (excluding lung & CRC) | 9212 | 9375 |

Table 4 shows the results of the HSQ surveys on non-protocol PSA testing. For the entire post-screening period, rates were similar across arms for testing within the past year, both for screening (45.0% and 45.9% for intervention and control arm, respectively) and for any reason (52.5% and 54.6% for the intervention and control arm, respectively). These rates varied little over study time periods in the post-screening phase (table 4). These corresponding rates during the screening phase in the control arm were slightly lower (40.1% and 47.3% for screening and testing for any reason, respectively). Ever PSA testing rates during the post-screening phase were 99% for the intervention arm and 86% for the control arm.

Table 4.

PSA testing rates from HSQ surveys

| Time Period | Trial Arm | Total surveyed1 |

PSA Test within past year for screening |

PSA Test within past year for any purpose |

PSA Test within past 3 years for any purpose2 |

PSA Test ever for any purpose2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Year 0–53 | Control | 2214 | 46.0 | 52.5 | 67.9 | 78.9 |

| Study Year 6–9 | Intervention | 861 | 47.6 | 54.4 | 88.9 | 98.8 |

| Control | 1068 | 45.6 | 54.6 | 78.4 | 83.6 | |

| Study Year 10–13 | Intervention | 702 | 43.7 | 53.1 | 73.7 | 98.9 |

| Control | 807 | 47.5 | 56.4 | 80.2 | 88.1 | |

| Study Year 14–17 | Intervention | 294 | 40.5 | 45.6 | 71.1 | 99.3 |

| Control | 339 | 43.1 | 50.2 | 76.4 | 87.9 | |

| All post-screening study years (6–17) | Intervention | 1857 | 45.0 | 52.5 | 80.3 | 98.9 |

| Control | 2214 | 45.9 | 54.6 | 78.7 | 85.9 |

Total surveyed excludes unknowns and those with prior prostate cancer diagnosis. Percentages exclude both groups.

For intervention arm, rates include PLCO protocol screening tests taken in the relevant time period (for tests within the past 3 years) or at any time (for PSA tests ever). Note the intervention arm HSQ survey only asks about PSA tests taken outside of the PLCO protocol.

Adjusted to included “baseline contaminated” subjects. See text for details.

In the intervention arm, compliance rates for PSA screening were 89.4%, 87.2%, 86.4%, 85.1%, 78.4% and 78.3% for study years 0–5 (average, 84.1%). By protocol, 80.0% of intervention arm men were scheduled to receive all 6 PSA tests, 16.4% were scheduled to receive 5 PSA tests and 3.6% were scheduled to receive 4 PSA tests, based on their randomization date. A total of 93.6% of intervention arm men received at least one protocol PSA screen.

Discussion

In this extended follow-up of the prostate component of the PLCO trial, median follow-up increased by about three years, maximum follow-up increased by six years, and prostate cancer deaths increased by 65% from the prior analysis. The risk ratio (intervention arm compared to usual care) for prostate cancer mortality remained slightly above one, with a value of 1.04 (95% CI: 0.87–1.24), down from 1.09 in the prior analysis (the lower 95% confidence limit remained unchanged at 0.87).

With a median follow-up of almost 15 years, the majority of deaths from prostate cancer (around 60% in each arm) still occurred in cases diagnosed during the screening phase of the trial (first 6 years). This indicates the need for long-term follow-up, perhaps even longer than 15 years, to fully capture the potential mortality effects of PSA screening.

As with any null trial, statistical power is a critical issue. The original power analysis performed near the start of the trial showed a 90% power for a 20% mortality reduction across arms12. This power value was based on estimated event rates (for control arm prostate cancer deaths), predicted compliance and contamination rates, and an estimated “true” mortality effect of screening with perfect compliance and no contamination. A revised analysis, based in part on longer follow-up (13 years instead of 10) showed similar 90% power assuming a 38% contamination rate (specifically, 38% of control arm men received yearly screening) and 90% compliance (averaged over screening rounds) and the same true mortality effect (of 27%)13. A common critique of the PLCO prostate trial has been that the original (and revised) power estimate was too high, based both on higher levels of contamination and lower numbers of events than predicted. With extended follow-up and about 65% more prostate cancer deaths in the current analysis, the second factor has been mitigated to some extent.

With respect to contamination, using the original trial definition (screening PSA test in the past year), the rate reported here of 46% in the screening phase is only modestly higher than the above 38%. However, the effect on power of non-yearly testing during the screening phase, reflected, for example, in the 67.9% rate of receiving PSA testing in the past 3 years, and the effect of high, even if equal across arms, control arm screening in the post-screening phase is not clear. The model used for the above power computations assumed no control arm PSA testing outside of the 38% receiving yearly screening, and no post-screening phase testing in either arm12. More complex modeling is needed to assess the effect on trial power of the observed pattern of non-protocol control (and intervention) arm use of PSA. The average 84% compliance rate for PSA screening in the intervention arm is substantially greater than the 46% comparable screening phase control arm rate, and the prostate cancer incidence risk-ratio of 1.27 during that phase clearly shows more screening in the intervention than control arm during that period. On the other hand, with most control arm men (86%) receiving some PSA testing during the trial, and with almost half receiving annual screening, the dilution of power due to contamination is likely to have been substantial.

Given the high control arm use of PSA testing, PLCO has often been described as a trial of organized screening versus “opportunistic” screening. Viewed in this light, the assumed reduction in prostate cancer mortality in the intervention compared to control arm would be considerably less than the 27% true mortality reduction referred to above, since both arms would be receiving some screening, but there would be, by definition, no “contamination”. The actual power of the trial is the same, whichever way the trial is regarded, but in this interpretation the power is reduced because the postulated expected mortality reduction between arms is lowered. Therefore, the trial can be viewed as showing no mortality benefit of organized versus opportunistic screening, with somewhat low power due to an expected modest difference in prostate cancer mortality between arms.

In addition to power, another important consideration for null trials is the width of the confidence interval on the primary endpoint. With this extended follow-up, the lower 95% CI for the mortality relative risk was unchanged from the prior analysis, at 0.87. Even though the width of the entire confidence interval was narrowed due to the larger number of events, the point estimate was decreased towards 1.0, resulting in an unchanged lower 95% CI. It is important to interpret this lower limit correctly. Due to the high contamination rate, it should not be considered as the lower 95% bound on the “true” mortality effect (as defined above) of prostate screening. Rather, under the interpretation of PLCO as a trial of an organized screening program versus “opportunistic screening”, the lower 95% bound should be interpreted in that context. In other words, organized screening compared to opportunistic screening could give a mortality benefit as high as 13% (or a harm as much as 24%).

An analysis by non-PLCO investigators suggested that a higher percentage of PLCO control arm than intervention arm men received any PSA tests14. This is not correct, as the analysis neglected to take into account the fact that the HSQ survey data for the intervention arm only concerned non-PLCO protocol PSA tests15. As seen here, and reported elsewhere, the true rate of ever-PSA testing was 99% in the intervention arm, and 86% in the control arm15.

Recently, the results of the PROTECT trial, which compared curative treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) to active monitoring in men with screen detected localized prostate cancer, were reported16. Deaths from prostate cancer over a median 10 years of follow-up were very low in each arm, at most 1.5%, and no significant difference was observed between the active monitoring and curative treatment arms. The incidence of metastases was statistically significantly higher in the active monitoring arm, although the overall rate (6%) was low. Since the efficacy of screening is premised on the assumption that earlier treatment leads to reduced prostate cancer deaths, the PROTECT results raise provocative questions as to the timing and magnitude of any effect of screening on prostate cancer mortality.

An intriguing finding was the borderline significant reduction in all-cause mortality in the intervention arm (p-value of 0.06 and 0.11 for the risk ratio and hazard ratio, respectively). This borderline association was also reported in a prior analysis of PLCO with follow-up through 13 years6. It is possible that the increased contact with medical professionals brought on by screening, and not just for prostate cancer but for lung and colorectal cancer as well, might have resulted in decreased mortality. However, this is more likely a chance finding, especially given the fact that examination of the causes of death shows no clear pattern by trial arm.

Conclusion

Extended follow-up of the PLCO trial through up to 19 years continues to show no prostate cancer mortality benefit of screening with PSA and DRE for the intervention compared to the control arm. Due to the high rate of control arm PSA testing, this finding can be viewed as showing no benefit of organized over opportunistic screening with PSA.

Acknowledgments

Funding: funded in part through NCI contract HHSN261201100008C (Andriole, Grubb, Crawford); other authors are NIH employees.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Cancer Statistics Review. [Accessed July 5th, 2016]; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/

- 2.Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:762–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer VA U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:120–134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–2035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Prostate-Cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. New Engl J Med. 2012;384:2027–2035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, et al. Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: Mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andriole GL, Grubb RL, Buys SS, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate cancer screening trial. New Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller AB, Feld R, Fontana R, et al. Changes in and impact of the death review process in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Reviews Recent Clinical Trials. 2015;10:206–211. doi: 10.2174/1574887110666150730120752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black A, Huang W, Wright P, et al. PLCO: Evolution of an epidemiologic resource and opportunities for future studies. Reviews Recent Clinical Trials. 2015;10:238–245. doi: 10.2174/157488711003150928130654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy SA, Van Der Vaart AW. On profile likelihood. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:449–465. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J Royal Stat Society, Series B. 34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prorok PC, Andriole GL, Bresalier R, et al. Design of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin. Trials. 2000;21(6S):273S–309S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinsky PF, Black A, Kramer BS, et al. Assessing contamination and compliance in the prostate component of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Clinical Trials. 2010;7:303–311. doi: 10.1177/1740774510374091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoag J, Mittal S, Hu JC. Reevaluating PSA testing rates in the PLCO Trial. New England J Med. 2016;374:1795–1796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinsky P, Prorok P. Re: Reevaluating PSA testing rates in the PLCO Trial. New England J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1607379. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. New Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]