Abstract

Purpose

To assess the efficacy and toxicity of sorafenib as front-line therapy in patients with stage IIIB (pleural effusion) or IV NSCLC.

Methods

Patients received sorafenib 400 mg twice daily by mouth continuously, and were evaluated every 2 weeks during the first 8 weeks. Patients who manifest clinical progression during this period proceed to receive standard of care. The primary endpoint was confirmed objective tumor response. A two-stage Fleming design was utilized such that if at most one confirmed partial (PR) or complete response (CR) was observed in the first 20 patients (Stage 1), the treatment would be considered ineffective and further enrollment would be discontinued.

Results

Only 1 PR was observed in the first 20 patients. By the time of study closure, 5 additional patients who were already being screened for study inclusion were enrolled. Of the 25 patients, [15 females, 10 males; 4 stage IIIB, 21 stage IV; median age 67(45-85)] there were 3 (12%) PRs; and 6 (24%) stable disease (SD) observed. The median time-to-progression and progression-free survival was 2.8 months. Seven (28%) patients remained progression-free at 24 weeks. No grade 3 or higher hematologic adverse events were observed. Thirteen (52%) patients had a grade 3 non-hematologic adverse event with fatigue (20%), diarrhea (8%), and dyspnea (8%) being the most common.

Conclusion

Sorafenib is not effective as front-line therapy in the general unselected NSCLC population. The “window of opportunity” design is feasible for estimating the activity of novel compounds.

Introduction

Lung cancer is currently the leading cause of cancer mortality in the US and throughout the world.1 In 2008, it is estimated that 215,250 individuals will be diagnosed with lung cancer in the US.1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprises over 75% of lung cancers and has been particularly difficult to treat effectively. Curative resection is possible in only 30% of patients at diagnosis, with metastatic disease developing in 50% of patients within 5 years.2

Increased understanding of lung cancer at the molecular level has allowed the development of novel targeted therapies for this disease,3 and the use of these agents in NSCLC continues to grow. A wide variety of prognostic factors that predict response to targeted agents are being investigated for NSCLC, and include tumor suppressor genes (p53 and Rb), growth factor receptors (epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR]), and dominant oncogenes (Ras).4 Angiogenesis has also been implicated in growth and metastatic processes in various malignancies including lung cancer, whereby inhibition of vascular endothelial.growth factor receptor (VEGFR) signaling has demonstrated clinical benefit.5-7

Sorafenib (Nexavar®; BAY 43-9006) is a multi-kinase inhibitor of Raf-1, wild-type B-Raf, oncogenic b-raf V599E, VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR-β, c-Kit, Flt-3, and RET in vitro.8,9 Sorafenib inhibited the growth of a variety of tumor xenograft models driven by upregulation of Raf/MEK/ERK signaling.8 Sorafenib also blocked tumor proliferation and angiogenesis,8 and promoted apoptosis in several cancer cell lines including NSCLC.10 Tolerability and preliminary efficacy of sorafenib were investigated in four dose-escalation Phase I trials in patients with treatment-refractory, advanced solid tumors.11-14 The optimum dose established was sorafenib 400 mg twice daily (bid), given in an uninterrupted schedule.11-14 Clinical activity with significant partial responses or prolonged disease stability was demonstrated in patients with hepatocellular and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) .12,13,14 Sorafenib also demonstrated anti-tumor activity and tolerability in Phase I combination trials, with no clinically relevant drug interactions seen with concomitant administration of interferon-α2,15 carboplatin/paclitaxel,16 gemcitabine,17 or oxaliplatin.18

Sorafenib (400 mg bid) monotherapy was further evaluated in a Phase II randomized discontinuation trial in advanced RCC patients, which demonstrated a significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) versus placebo.19 Sorafenib induced disease restabilization in patients whose tumors progressed on placebo and whom were crossed over to sorafenib.19 This was confirmed in a Phase III trial (Treatment Approaches in Renal cancer Global Evaluation Trial [TARGETs]) involving patients with clear-cell RCC.20 Sorafenib significantly prolonged PFS 2-fold versus placebo, and was generally well tolerated. Ten percent of patients receiving sorafenib had partial responses, and 78% of patients had stable disease versus 2% and 55% on placebo (p< 0.001 and p<0.01, respectively). Sorafenib has thus been approved in several countries worldwide for the treatment of RCC. It has also been granted orphan drug status in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) by the FDA and European Commission based on superior PFS and overall survival compared to placebo.21,22

It had been assumed that the efficacy of novel agents in NSCLC will be more accurately determined if these agents were tested in the front-line setting due to emergence of mutations arising from exposure to various therapies, thus conferring treatment resistance over time.23 Based on this assumption we designed a front-line “window-of-opportunity” study. Patients with previously untreated NSCLC received single-agent sorafenib, and were closely monitored, with intent to introduce platinum-based chemotherapy at the initial sign of progression.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Patients with histologic or cytologic evidence of measurable metastatic or stage IIIB (with malignant pleural effusion) NSCLC with no prior chemotherapy were eligible for this study. Eligibility criteria also included age ≥ 18 years; ECOG performance status ≤ 2; prior radiation was not to encompass more than 30% bone marrow reserve, could not be of target lesions and should have been completed at least 4 weeks prior to study enrollment; life expectancy of at least 12 weeks; adequate bone marrow (platelets ≥ 100,000/μL, absolute neutrophil count > 1,500/μL, hemoglobin ≥ 10 g/dL), hepatic (total bilirubin ≤ 2. times the upper limit of normal, aspartate transaminase ≤ 3 times normal) and renal (serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal) function. Patients with brain metastases, those receiving therapeutic anticoagulation and those with bleeding diatheses were excluded. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards, and all patients were required to give written informed consent under Federal and institutional guidelines.

Experimental treatment

This was a Phase II, open-label, “window of-opportunity” study of sorafenib as front-line treatment for advanced NSCLC. Patients received sorafenib dosed at 400 mg BID continuously, with a cycle defined as 4 weeks. Patients were evaluated every 2 weeks during the first 2 cycles, with those who manifest clinical progression (.e.g. worsening symptoms, physical examination or test abnormalities, etc) proceeding to receive standard chemotherapy.

Clinical Care of Patients

Complete patient histories, physical examinations, complete blood cell counts, serum electrolytes, chemistries and urinalysis were performed at baseline and prior to each cycle of treatment. Home blood pressure monitoring was performed to evaluate the incidence and severity of hypertension. Laboratory studies were repeated weekly together with evaluation for clinical progression. Unless there was evidence of clinical progression, radiologic studies (CT, MRI) were performed at baseline and after every two cycles of therapy to assess tumor response. Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 3 (CTCAEv3.0) was used for adverse event monitoring and reporting. Criteria for discontinuation from study included: CTC grade 3/4 drug-related toxicity requiring a treatment delay ≥ 2 weeks, progressive disease, withdrawal of consent, or change in patient's condition that made further treatment inappropriate.

Statistical Design

A two-stage phase II study based on a Fleming design was conducted to assess the antitumor efficacy of this regimen. The primary endpoint was confirmed tumor response rate (RR). A treatment success was defined as either a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) observed on 2 consecutive evaluations greater than 4 weeks apart. This trial was designed to test the null hypothesis that the true treatment success rate was at most 5% against the alternative that it was at least 20% using a sample size of 42 pts with a significance level of 0.10 and power of 90%. To test this hypothesis, 20 patients were to be entered for stage 1 enrollment. If at most one success was observed, the treatment would be considered ineffective in this patient population and enrollment would be discontinued. If at least 4 confirmed responses were observed, the regimen would be considered promising and the trial results published. If 2 or 3 successes were observed in stage 1, we were to proceed to stage 2. During stage 2, we were to enter an additional 22 patients. If 4 or fewer confirmed responses were observed for the entire cohort, this regimen was to be deemed ineffective for this patient population. If at least 5 confirmed responses were observed, this regimen was to be deemed promising and recommended for further testing.

Survival time was defined as the time from registration to death due to any cause. Time-to-progression was defined as the time from registration to the date of first documented disease progression. If a patient died without documentation of disease progression, the patient was considered to have had tumor progression at the time of death, unless there was sufficient documented evidence to conclude otherwise.

Tumor response was collected on this trial using the RECIST criteria.24 Confirmed tumor RR is computed as the number of confirmed CR or PR divided by the total number of evaluable patients. Exact binomial confidence intervals for the true treatment success rate were constructed.25. The distribution of time-to-progression and overall survival time was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier Method.26 The duration of response was defined as beginning from the time the measurement criteria for a CR/PR were first met until documentation of disease progression for those patients who had objectively responding (CR or PR) disease. The duration of stable disease was calculated as the time from the first assessment of stable disease to documentation of disease progression. Adverse event data was collected on this trial using version 3.0 of the Common Toxicity Criteria. The maximum grade for each type of adverse event was recorded over the course of treatment and summarized for analysis. All adverse events were included in analysis regardless of treatment attribution.

Since this was a single arm trial, the observed overall survival of this cohort of patients was compared to a predicted survival estimate for a similar cohort of patients, where the predicted survival probabilities for each patient were calculated using the prognostic model based on an underlying Cox Proportional Hazards model previously described by the NCCTG lung group.27 Pretreatment performance status, hemoglobin levels and absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) were used to predict the survival probability of each patient at each unique observed failure time. Since ANC values were collected in this trial rather than white blood cell counts (WBC) the model described by the NCCTG lung group 27 was rerun to incorporate baseline ANC values rather than WBC. Body Mass Index was not included in the model as this was not collected for this trial. The probabilities at each failure time were then averaged across patients to obtain the predicted survival curve. The observed survival was then visually compared with the predicted survival in an effort to understand the impact of this regimen compared to the survival of patients with similar prognostic factors who received systemic therapy on previous NCCTG trials.

Results

A total of 25 patients were enrolled on this trial between December 2004 and June 2005. Although there was a discontinuation of enrollment between the first and second stages of this trial, 5 additional patients from multiple sites had, given consent and been registered for the study prior to release of study suspension memo after the initial 20 evaluable patients were accrued, and thus a total of 25 patients were allowed to be enrolled prior to the efficacy evaluation. Four patients remain alive with a median follow-up of 40 months (range 15.7 – 40.9 months). All patients were deemed eligible and were evaluable for all study endpoints. The median age was 67 years (range 45 – 85). Sixty percent of patients were female, 92% white, 48% had a performance status of 0, and 84% presented with stage IV disease. Fifty-two percent of patients had adenocarcinoma, 20% squamous cell, 20% other NSCLC (not otherwise specified), 4% bronchioalveolar, 4% unidentified (1 patient with NSCLC of unverified histologic subtype). See Table 1 for a summary of baseline characteristics. Smoking status was not collected for this trial. The median number of treatment cycles received was 3, with a range from 1 to 26. Twenty-two of the 25 participants (88%) went off treatment due to disease progression; 1 patient went off study treatment due to refusal to receive further therapy, 1 patient died on study, and 1 patient discontinued study treatment due to unresolved psychiatric issues.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range): | 67 | (45-85) |

|

| ||

| Gender: | ||

| Female | 15 | (60.0) |

| Male | 10 | (40.0) |

|

| ||

| Race: | ||

| White | 23 | (92.0) |

| Asian | 1 | (4.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | (4.0) |

|

| ||

| Performance Score: | ||

| 0 | 12 | (48.0) |

| 1 | 10 | (40.0) |

| 2 | 3 | (12.0) |

|

| ||

| Lung Stage: | ||

| IIIB w/pleural effusion | 4 | (16.0) |

| IV | 21 | (84.0) |

|

| ||

| Histology: | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 13 | (52.0) |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 5 | (20.0) |

| NSCLC, not otherwise specified† | 6 | (24.0) |

| Bronchioalveolar Carcinoma | 1 | (4.0) |

|

| ||

| Coumadin: | ||

| Yes | 1 | (4.0) |

| No | 24 | (96.0) |

|

| ||

| Median ANC (×109/L) (range): | 5.7 | (2.2-19.8) |

|

| ||

| Median Hgb (g/dL) (range): | 12.8 | (11.0-17.5) |

|

| ||

| Median INR Part I* (range): | 10.7 | (1.0-46.2) |

|

| ||

| Median INR Part II* (range): | 1.0 | (0.8-1.2) |

International Normalized Ratio: _ . _ : _ . _

Includes one patient with NSCLC but histologic subtype unverified

Adverse Events

Adverse events reported on this trial were generally mild with no reported grade 3+ hematologic events. At least 1 grade 3+ non-hematologic event during the course of the trial was reported in 13 (52%) patients. The most common (events reported in 5% or more of patients) grade 3 events reported included fatigue (20%), diarrhea (8%) and dyspnea (8%). A grade 4 pulmonary hemorrhage was reported in one patient with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a large cavitary left upper lobe mass. This patient was hospitalized due to grade 3 dyspnea a week prior to the hemorrhagic event. No pulmonary embolism was found though post-obstructive pneumonia was diagnosed and subsequent treatment was rendered accordingly. The day after hospital discharge, patient had grade 5 hypoxia and grade 4 pulmonary hemorrhage judged most likely related to tumor erosion into the pulmonary vasculature by the treating physician. However, contribution from study treatment cannot be totally excluded. See Tables 2 and 3 for more detail on reported adverse events. All adverse events are included regardless of treatment attribution.

Table 2. All Severe (Grade 3+) Adverse Events.

| Adverse Event | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Fatigue | 5 | (20.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 2 | (8.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Dyspnea | 2 | (8.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hypoxia | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (4.0) |

| Pulmonary Hemorrhage | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Acne | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Anorexia | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Anxiety | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Cough | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Depression | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hand/Foot Skin Reaction | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hemorrhoids | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hyponatremia | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Neuro – Motor | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Neuro – Sensory | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain – Bone | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain – Rectal | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Psychosis Aggravated | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Tachycardia – Supraventricular | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

Table 3. Adverse Events Occurring in 10% or More of Patients.

| Body System | Adverse Event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Constitutional Symptoms | Fatigue | 8 | (32.0) | 7 | (28.0) | 5 | (20.0) |

| Weight Loss | 12 | (48.0) | 4 | (16.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Fever | 4 | (16.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Gastrointestinal | Anorexia | 11 | (44.0) | 4 | (16.0) | 1 | (4.0) |

| Diarrhea | 8 | (32.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 2 | (8.0) | |

| Nausea | 8 | (32.0) | 4 | (16.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Mucositis/Stomatitis (Functional/Symptomatic) – Oral Cavity | 6 | (24.0) | 3 | (12.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Mucositis/Stomatitis (Clinical Exam) – Oral Cavity | 9 | (36.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Vomiting | 4 | (16.0) | 3 | (12.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Dermatology/Skin | Acne NOS | 9 | (36.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 1 | (4.0) |

| Hand/Foot Skin Reaction | 7 | (28.0) | 3 | (12.0) | 1 | (4.0) | |

| Alopecia | 3 | (12.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension | 7 | (28.0) | 4 | (16.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Pain – Chest | 1 | (4.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Hematology | Anemia | 7 | (28.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Neutropenia | 3 | (12.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 | (20.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Leukopenia | 4 | (16.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Metabolic/Laboratory | Alk Phosphatase | 5 | (20.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 | (8.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Hypocalcemia | 3 | (12.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Pulmonary | Cough | 2 | (8.0) | 3 | (12.0) | 1 | (4.0) |

| Dyspnea | 2 | (8.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 2 | (8.0) | |

| Hepatic | SGOT (AST) | 5 | (20.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| SGPT (ALT) | 3 | (12.0) | 2 | (8.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Neurology | Neuro – Sensory | 2 | (8.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 1 | (4.0) |

| Dizziness | 2 | (8.0) | 1 | (4.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

Efficacy

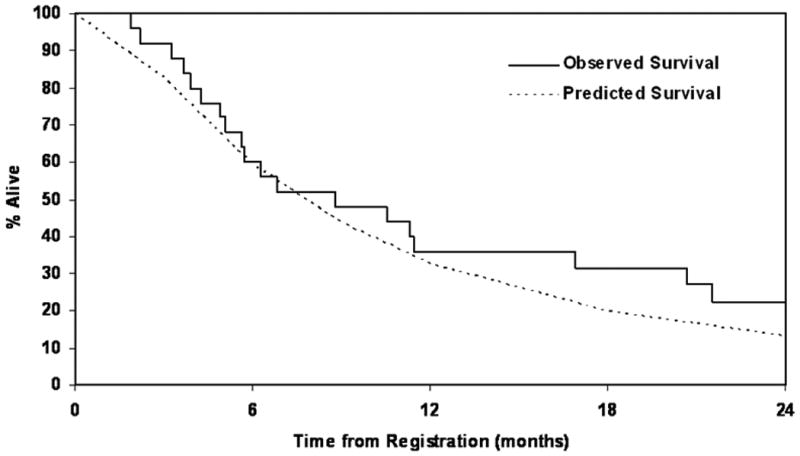

Only 1 partial response was observed in the first 20 patients, thus the study did not meet the first stage efficacy criteria. A total of 3 PRs (12% RR, 95% CI: 2.6-31.2%)) and 6 SD (24%, 95% CI: 9.4-45.1%)) were observed in the 25 pts. The median duration of response for these 3 PR patients was 2.7 months with a range of 2.5 – 15.7 months. The median duration of stable disease for the 6 SD pts was 7.5 months with a range of 1.5 – 23.9 months. Progression-free status at 24 weeks was also evaluated in addition to response, with 7 patients (28%, Exact CI: 12.1% - 49.4%) remaining progression-free at 24 weeks. The median time-to-progression and overall survival was 2.8 months (95% CI=1.8 – 4.6 months) and 8.8 months (95% CI=5.1 – 16.9 months), respectively. The estimates for PFS were identical to time-to-progression (due to classification as disease progression at the time of death). See Figure 1 for Kaplan Meier overall survival curve for the entire cohort as well as the predicted survival curve. The observed overall survival of patients was comparable to the predicted survival for this cohort. The Kaplan Meier curve for time to progression is given in Figure 2. While there are no survival differences according to histology, interpretation of subset analysis is limited by the small population of patients.

Figure 1. Observed Overall Survival Using the Kaplan Meier Method and the Predicted Overall Survival Based on a Prognostic Cox Model Adjusted for Baseline Patient Characteristics.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Plot for Time to Progression.

Data on subsequent treatment upon disease progression was not standardly collected on this trial, and was available on nine (36%) patients: 3 patients did not receive further therapy, 2 patients received only radiation therapy, and 4 patients received systemic therapy (two received platinum-based combination, one received docetaxel, and one received erlotinib).

Discussion

NSCLC, which to date is a relatively chemoresistant malignancy, is the leading cause of cancer death throughout the world, largely because approximately 50% of lung cancer cases present in the advanced stages. Although there have been increased systemic therapy options for NSCLC over the years, the clinical outcome is still dismal. The median survival of patients with advanced disease receiving the best triplet therapy is approximately 12 months and response rates range from 35 to 50%.28,29

The clinical efficacy of targeted agents such as erlotinib and gefitinib has demonstrated an approximately 10% response rate as monotherapy in patients with previously treated, chemotherapy-refractory advanced NSCLC.30, 31 Antitumor activity in second and third-line settings may be limited, evidently by known redundancies within the network of cross-signaling pathways as well as by the emergence of pleiotropic mechanisms of resistance due to genetic instability in cancer cells. Related to this is the less recognized but documented effect of chemotherapy exposure in altering expression patterns of potential drug targets.32-34 To address this issue, the “window-of-opportunity” design has been suggested as an alternative design to test the true efficacy of a new agent in a particular disease prior to any therapy. Opponents of this approach raise ethical concerns with the use of an agent with unknown efficacy when an accepted standard therapy is available. We demonstrated that when the study is carefully designed to closely monitor patients, this approach is feasible and ethical.

In this study, sorafenib as a single agent achieved a response rate of 12% in the 25 patients. While these results did not meet the protocol-defined pre-specified criteria for success, they do document activity of sorafenib as a single agent in NSCLC. This response rate is in contrast to the lack of objective response (response rate 0%) documented in one single-arm second-line study of sorafenib in NSCLC,35 suggesting that indeed, cross-trial differences aside, there is a distinct possibility of a higher response rate when sorafenib is used as front-line therapy. A similar conclusion can be reached when comparing our results with the report by Schiller et al wherein sorafenib was tested in a phase II randomized discontinuation design (versus placebo) in heavily pre-treated NSCLC patients (patients must have received at least two prior chemotherapy regimens).36 Among 342 patients who received sorafenib during the run-in phase, 2% had a partial PR. Among the 83 patients who had stable disease after 8 weeks of monotherapy and subsequently randomized to either placebo or sorafenib therapy for another 8 weeks, 3% and 2% of patients in the placebo and sorafenib group, respectively had a PR, whereas another 6% in the placebo group sustained a PR upon cross-over.36 This study met its endpoint of disease stabilization at 8 weeks following randomization compared to placebo (47% versus 19%, p<0.01).

Overall survival of the patients in our study was comparable to the predicted survival for this cohort, based on a previously published NCCTG prognostic model.27 The influence of second line therapy on the OS estimates is unclear as subsequent treatment information was not systematically collected and thus unavailable for 64% of the patients in this trial. While this implies that sorafenib followed by chemotherapy is unlikely to improve survival compared to chemotherapy alone, a notable observation is that the 24-week PFS with sorafenib therapy is comparable to that seen in similar population of patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy27, 37, suggesting the likelihood of benefit in a select group of patients in various settings, such as in ‘maintenance’ therapy after first-line platinum-based combination chemotherapy regimen. Whether our observation of prolonged PFS in certain patients may be attributed to underlying tumor biology itself or the interaction with drug treatment cannot be ascertained. Because of the small sample size which precluded a valid interpretation of correlative data, no biomarkers were evaluated. This is a limitation of the study.

Results from a randomized phase III study (ESCAPE) of first-line carboplatin and paclitaxel with our without sorafenib in advanced NSCLC have been recently reported.38 The study was terminated after a planned interim analysis of the 926 patients enrolled showed no difference in response rate, PFS or its primary endpoint of OS. In a subset analysis, patients with tumors of squamous cell histology who received sorafenib in combination with chemotherapy had worse overall survival than patients receiving chemotherapy alone (8.9 vs 13.6 months, HR 1.85). Other VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as cediranib, motesanib, etc., multi-kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib and dual EGFR/VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as vandetanib, have been studied as single-agent therapies or in combination with chemotherapy. An apparent recurring theme that emerged is the finding of worse clinical outcomes in patients with squamous cell histology in some of the chemotherapy combination studies. This has led to temporary suspension of several phase III studies (e.g. MONET1, NEXUS), with subsequent study enrollment limited to patients whose tumors were nonsquamous in histologic type. On a contrary note, the phase III study of cediranib in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel revealed that response rate and PFS was improved upon addition of cediranib but the dose of 30mg once daily was poorly tolerated. Analysis did not reveal increased risk of pulmonary bleeding in patients with squamous histology and there was no evidence of interaction of efficacy outcomes with histologic subtype.39

In conclusion, while this study failed to meet its efficacy endpoint, the “window – of – opportunity” design was helpful in documenting clinical activity of sorafenib in NSCLC. Based on the lack of benefit and in fact, evidence of poorer survival with sorafenib when combined with paclitaxel/carboplatin in squamous cell lung cancer,38 it is possible that exclusion of squamous cell lung cancer patients from sorafenib studies of NSCLC may reveal a more robust clinical efficacy profile. However, we acknowledge that this is speculative and that the impact of histology on the outcomes could not be reliably evaluated in this trial due to the small sample size. Further studies of sorafenib along this line, as well as rational combinations with other targeted agents are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patients and their families as well as Ms Raquel Ostby for expert secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

This study was conducted as a collaborative trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic and was supported in part by Public Health Service grants CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-37417, CA-35103, CA-52352, CA-35415, CA-35113, CA-63848, CA-35195 and CA-35101. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institute of Health.

Additional participating institutions include: Medcenter One Health Systems, Bismarck, ND 58506 (John T. Reynolds, M.D.); Metro-Minnesota Community Clinical Oncology Program, St. Louis Park, MN 55416 (Patrick J. Flynn, M.D.); Cedar Rapids Oncology Project CCOP, Cedar Rapids, IA 52403 (Martin Wiesenfeld, M.D.); Illinois Oncology Research Assn. CCOP, Peoria, IL 61615-7818 (John W. Kugler, M.D.); Altru Health Systems, Grand Forks, ND 58201 (Todor Dentchev, M.D.); Iowa Oncology Research Association CCOP, Des Moines, IA 50309-1014 (Roscoe F. Morton, M.D.); Michigan Cancer Research Consortium, Ann Arbor, MI 58106 (Philip J. Stella, M.D.); Rapid City Regional Oncology Group, Rapid City, SD 57709 (Richard C. Tenglin, M.D.); Toledo Community Hospital Oncology Program CCOP, Toledo, OH 43623 (Paul L. Schaefer, M.D.)

Pharmaceutical Research Support: Bayer Pharmaceuticals

Previous Presentations: (Abstract): Adjei AA, Molina JR, Hillman SL, Luyun RF, Reuter NF, Rowland Jr KM, Jett JR, Mandrekar SJ, Schild SE. A front-line window of opportunity phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol. 25, No. 18S (June 20, Supplement) 2007: 7547.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Statistics 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fossella FV, Lee JS, Hong WK. Management strategies for recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dy GK, Adjei AA. Systemic cancer therapy: evolution over the last 60 years. Cancer. 2008;113:1857–1887. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scagliotti GV, Masiero P, Pozzi E. Biological prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1995;1(suppl 12):S13–S25. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00417-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkman J. Antiangiogenic gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;95(16):9064–9066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18(1):4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2542–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral anti-tumor activity and targets the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7099–7109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlomagno F, Anaganti S, Guida T, et al. BAY 43-9006 inhibition of oncogenic RET mutants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:326–334. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj069. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu C, Bruzek LM, Meng XW, et al. The role of Mcl-1 downregulation in the proapoptotic activity of the multi kinase inhibitor BAY 43-9006. Oncogene. 2005;24:6861–6869. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore M, Hirte HW, Siu L, et al. Phase I study to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel Raf kinase and VEGFR inhibitor BAY 43-9006, administered for 28 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1688–1694. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awada A, Hendlisz A, Gil T, et al. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetics of BAY 43-9006 administered for 21 days on/7 days off in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1855–1861. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43-9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:965–972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JW, Eder JP, Ryan D, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of the dual action Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, BAY 43-9006, in patients with advanced, refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5472–5480. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escudier B, Lassau N, Angevin E, et al. Phase I trial of sorafenib in combination with IFN alpha-2a in patients with unresectable and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1801–1809. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flaherty KT, Brose M, Schuchter LM, et al. Sorafenib combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel for metastatic melanoma: PFS and response versus B-Raf status. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:iii33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siu LL, Awada A, Takimoto CH, et al. Phase I/II trial of sorafenib and gemcitabine in advanced solid tumors and in advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:144–151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kupsch P, Henning BF, Passarge K, et al. Results of a Phase I trial of sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) in combination with oxaliplatin in patients with refractory solid tumors, including colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2005;5:188–196. doi: 10.3816/ccc.2005.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratain MJ, Eisen T, Satdler WM, et al. Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(16):2505–2512. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldie JH, Coldman AJ. The genetic origin of drug resistance in neoplasims: implications for systemic therapy. Cancer Res. 1984;44(9):3643–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duffy D, Santner T. Confidence intervals for a binomial parameter based on multistage tests. Biometrics. 1987;43:81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandrekar S, Schild SE, Hillman S, et al. A prognostic model for advanced stage nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:781–792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirker R, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, et al. FLEX: randomized, multicenter, phase III study of cetuximab in combination with cisplatin/vinorelbine (CV) versus CV alone in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15S) abstr 3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossi G, Cavazza A, Marchioni A, et al. Kit expression in small-cell carcinomas of the lung: effects of chemotherapy. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:1041–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000089780.30006.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujita K, Miyamoto T, okada Y, et al. Expression pattern of sonic hedgehog and effect of topical mitomycin C on its expression in human ocular surface neoplasms. Jpn J ophthalmol. 2008;52(30):190–194. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasbridge SA, Gillett CE, Seymour AM, et al. The effects of chemotherapy on morphology, cellular proliferation, apoptosis and oncoprotein expression in primary breast carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1994;70(2):335–341. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenschein GR, Jr, Gatzemeier U, et al. Phase II, multicenter, uncontrolled trial of single-agent sorafenib in patients with relapsed or refractory, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4274–4280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiller JH, Lee JW, Hanna NH, et al. A randomized discontinuation phase II study of sorafenib versus placebo in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have failed at least two prior chemotherapy regimens: E2501. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15S) abstr 8014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Socinski MA, Saleh MN, Trent DF, et al. A randomized phase II trial of two dose schedules of carboplatin/paclitaxel/cetuximab in stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1068–1073. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scagliotti G, Novello S, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III trial study of carboplatin and paclitaxel alone or with sorafenib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 28(11):1835–1842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goss GD, Arnold A, Shepherd FA, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with either daily oral cediranib or placebo in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCIC clinical trials group BR24 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):49–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]