Abstract

Objectives

Readmission and death are frequent after a hospitalisation and difficult to predict. While many predictors have been identified, few studies have focused on functional status. We assessed whether performance-based functional impairment at discharge is associated with readmission and death after an acute medical hospitalisation.

Design, setting and participants

We prospectively included patients aged ≥50 years admitted to the Department of General Internal Medicine of a large community hospital. Functional status was assessed shortly before discharge using the Timed Up and Go test performed twice in a standard way by trained physiotherapists and was defined as a test duration ≥15 s. Sensitivity analyses using a cut-off at >10 and >20 s were performed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcome measures were unplanned readmission and death, respectively, within 6 months after discharge.

Results

Within 6 months after discharge, 107/338 (31.7%) patients had an unplanned readmission and 31/338 (9.2%) died. Functional impairment was associated with higher risk of death (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.15 to 5.18), but not with unplanned readmission (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.15). No significant association was found between functional impairment and the total number of unplanned readmissions (adjusted OR 1.59, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.67).

Conclusions

Functional impairment at discharge of an acute medical hospitalisation was associated with higher risk of death, but not of unplanned readmission within 6 months after discharge. Simple performance-based assessment may represent a better prognostic measure for mortality than for readmission.

Keywords: readmission, death, functional status, Timed Up and Go test

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large prospective cohort study evaluating the association of performance-based assessment with readmissions and death in medical inpatients aged ≥50 years.

Long follow-up time of 6 months without loss to follow-up.

Assessment of both readmissions and deaths, separately.

Single-centre study including only medical patients.

Introduction

After an acute care hospitalisation, readmissions are frequent, affecting 14%–22% of the patients within 30 days after hospital discharge, and are associated with significant costs as well for the patients themselves as for the healthcare systems.1–3 Factors that contribute to readmission are manifolds, including multimorbidity, complication of medical treatment, length of hospital stay, number of previous hospitalisations, socioeconomic factors, care coordination, monitoring, follow-up care and/or home support.1 4 5 In this complex equation, patient's functional impairment could intuitively be considered as a potential predictor for readmission, as it may capture overall health status, including cardiorespiratory reserve and risk of falls altogether.6 7

Few studies assessed the association between performance-based functional impairment and readmission.8–16 Although those studies reported mainly a significant association between functional impairment and readmission, they were often limited by a retrospective design, or by focusing on a specific setting such as surgical ward or rehabilitation care facilities or on specific populations such as older adults or patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or myocardial infarction. Functional impairment has also been associated with mortality in several studies in ambulatory care settings,16–25 while the few studies assessing this outcome after a hospitalisation found controversial results.12 14 26

Performance-based functional methods have been shown to perform better than self-reported assessment.27 One of the former is the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, a brief, objective and simple assessment of functional status that does not require any special competence or equipment, allowing a wide use in everyday practice.28 Unlike many tools to assess functional status, the TUG test gives information on both balance and cardiorespiratory capacity, and it was associated with overall health decline.6 It has been also shown not to suffer from ceiling effect limitations and to be related to executive function.29 These characteristics make it a good potential tool to assess the risk of readmission. We therefore hypothesised that the TUG test may be a good predictor of adverse health outcomes, such as readmission.

In summary, although the TUG test has been associated with death and to a lesser extent with readmission, few studies looked at the predictability of the TUG test in a broader population such as general medical inpatients. Our aim was therefore to assess the association of performance-based functional impairment at discharge of an acute medical hospitalisation with unplanned readmission and death in a prospective cohort study including medical patients aged 50 years or older.

Materials and methods

Reporting is in accordance with the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.30

Study design and population

In a prospective cohort study, we included all consecutive patients aged ≥50 years admitted to the Department of General Internal Medicine of a large secondary care hospital in Switzerland (Fribourg Cantonal Hospital, 115 beds, 4400 admissions per year), between April and September 2013. Our exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) discharge the day of admission; (2) discharge to another acute care clinic, a rehabilitation setting, a palliative care clinic or another division of the same hospital; (3) death during the index hospitalisation; and (4) refusal or inability to give informed consent. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and local ethics committee (Commission d’Éthique de Recherche, Direction de la Santé et des Affaires Sociales, Fribourg, Switzerland) approved the study. For this observational cohort without intervention, we did not perform a sample size calculation, and we limited the sample size due to the resources available.

Outcomes

We defined our primary outcome as the first unplanned readmission to any division of any acute care hospital and our secondary outcome as death, both within 6 months after discharge of index hospitalisation. We defined planned readmission as scheduled hospitalisation for investigation (eg, elective bronchoscopy) or for not emergent treatment (eg, planned radiotherapy for oncological treatment). All patients were contacted by phone call 6 months after discharge in order to record our outcomes. If we failed to reach the patient directly, we phoned the general practitioner, a next of kin or the nursing home, depending on each situation. To increase reliability, we additionally checked in the electronic health record for any readmission or death recorded within the network of Fribourg hospitals, which includes the three acute care hospitals of the same region (Fribourg, Riaz and Tavel) and four rehabilitation centres (Billens, Murten, Riaz and Tavel).

Functional status assessment

Patients performed the TUG test before discharge, according to its original description.28 They were instructed to stand up from a chair without using their arms, walk 3 m ahead (distance was marked on the floor), turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down. The duration to complete the test was timed by a stopwatch and recorded in seconds, beginning on the command ‘go’ given to the patient and ending after he/she had sit down and leaned against the back of the chair. The test was performed twice and the shortest time, indicating the best performance, was used for the analyses. Patients were allowed to use routine walking aids if needed (eg, crutches or walker), but they did not receive any physical assistance. Only three different trained physiotherapists performed the TUG test to all the cohort population. Patients who were too debilitated to perform the test were classified as having functional impairment.

We decided to dichotomize the results of the TUG test instead of using it as a continuous variable or in a higher number of categories because we thought that classifying patients at high versus low risk of readmission or death would be more useful to interpret for clinicians. As we found no agreement in the literature for a specific duration to sort out patients with functional impairment,7 we used the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to define the optimal cut-off level associated with our outcomes. For this purpose, we used the point closest to the top left corner of the ROC curve because it represents the best compromise between sensitivity and specificity.31 Functional impairment was defined as a TUG test duration longer than the cut-off level that we identified. The areas under the ROC curves were 0.57 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.64) for 6 month unplanned readmission and 0.63 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.73) for 6 month death. Both ROC curves identified the optimal cut-off level at 15 s. At this cut-off level, the sensitivity was 39.2% and 58.1% for unplanned readmission and death, respectively, and the specificity was 66.1% and 64.1%, respectively.

Covariates

Sociodemographic data, number of hospitalisations during the 6 months before index admission and clinical information were recorded at baseline. Comorbidity was assessed by the Charlson comorbidity index, which attributes a number of points of 1, 2, 3 or 6 to different medical conditions, depending on their severity,32 and multimorbidity was defined as the presence of at least two chronic diseases according to this index. The main diagnoses of index admission were retrieved from medical records and divided into 10 categories, according to the system affected: (1) osteoarticular disease, (2) gastrointestinal disease, (3) infection, (4) neuropsychiatric disease (including dementia, alcohol disorder and intoxication), (5) respiratory disease, (6) oncological disease, (7) endocrine or metabolic disease, (8) renal disease, (9) cardiovascular disease and (10) other.

Data analysis

We presented continuous variables as median with IQR because of their non-normal distribution, and we compared them using non-parametric K-sample test on the equality of medians. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage and compared using Pearson's χ2 test.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the association between functional impairment and unplanned readmission and death, respectively, within 6 months after hospital discharge. Multivariate analysis was adjusted for age and gender. A collinearity diagnostic measurement was performed to detect collinearity between the variables included in the model.33 A link test was used to confirm that the linear approach to model the outcome was correct.34 We used age as a continuous variable because assessing the variable in categories or after cubic or quadratic transformation yielded similar results. Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.35

We performed two sensitivity analyses including eight patients with missing data for the TUG test. We defined the duration of their non-performed TUG test as ≥15 s in the first one (ie, functional impairment) and as <15 s in the second one (ie, no functional impairment). As there was no agreement for a specific cut-off when dichotomizing the TUG test duration,7 although we used a validated method to select it,31 we also performed additional sensitivity analyses with the cut-off set at >10 and>20 s, respectively, as done in previous studies.12 14 22 We finally performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the patients who were too debilitated to perform the test. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed using STATA release 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

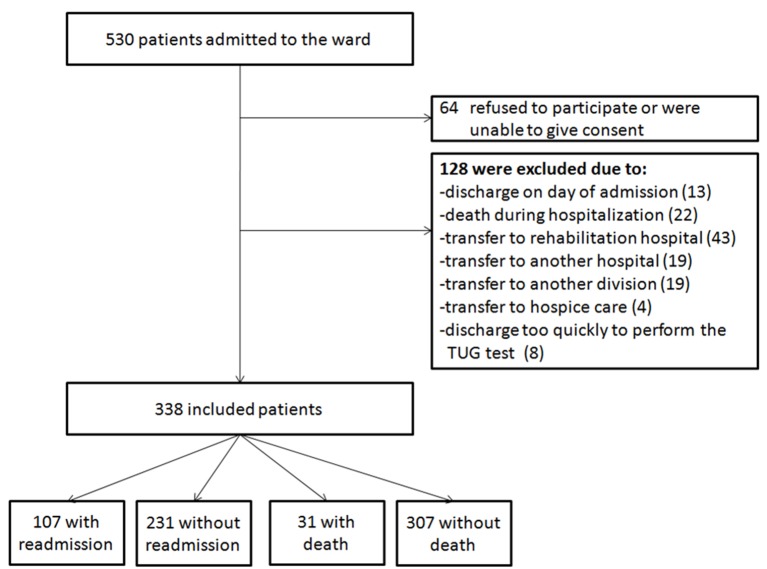

We included 338 patients (figure 1) and had no lost to follow-up, as we managed to get the outcome information per phone call (to the patient or to the general practitioner, a next of kin or the nursing home) for all patients. Median age was 73 (IQR 65–83) years with 168 (49.7%) men. Median Charlson comorbidity index was 5 (IQR 7–9) and 302 (89.4%) of the patients had multimorbidity. Median length of stay for index hospitalisation was 7 (IQR 4–12) days. Within 6 months after discharge, 107 (31.7%) patients had an unplanned readmission and 31 (9.2%) died. Among the 31 patients who died, 23 (74.2%) had been previously readmitted. Patients with functional impairment were older and more likely to be women and to have been admitted to hospital within the 6 months before index admission (p<0.003 for all). They had also a higher Charlson comorbidity index and a longer length of stay (p<0.001 for all). Cardiovascular, infectious and neuropsychiatric diseases were the three most frequent main diagnoses of index hospitalisation, with 91 (27%), 67 (20%) and 65 (19%) cases, respectively.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. TUG, Timed Up and Go.

Association of functional impairment with unplanned readmission and death

Table 1 and table 2 show the baseline characteristics according to the presence or absence of readmission or death, respectively. The median duration of the TUG test was 13 (IQR 10–19) s for patients with an unplanned readmission and 12 (IQR 8–18) s for those without any unplanned readmission (p=0.34). The TUG test duration was significantly longer among patients who died (median (IQR) duration: 17 (11–21) vs 12 (8–18) s, p=0.04). The duration of the TUG test was ≥15 s in 46 (43.0%) of the 107 patients with an unplanned readmission as well as in 18 (58.1%) of the patients who died within 6 months after hospital discharge.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the presence of 6 month readmission.

| Variable | 6 month readmission (n=107) | No 6 month readmission (n=231) |

| Age, years | 72 (64–83) | 74 (64–83) |

| Men | 57 (53.3) | 111 (48.1) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 8 (6–10) | 6 (4–8) |

| Multimorbidity* | 100 (93.5) | 202 (87.5) |

| Previous admission† | 51 (47.7) | 44 (19.1) |

| Duration of TUG test, seconds | 13 (10–19) | 12 (8–18) |

| TUG test duration ≥15 s | 46 (43.0) | 83 (35.9) |

| Hospitalisation characteristics | ||

| Elective | 3 (2.8) | 10 (4.3) |

| Length of stay, days | 9 (5–15) | 6 (4–11) |

| Diagnosis of index admission | ||

| Cardiovascular disease‡ | 25 (23.4) | 66 (28.6) |

| Infection | 20 (18.7) | 47 (20.4) |

| Neuropsychiatric disease§,¶ | 17 (15.9) | 48 (20.8) |

| Oncological disease | 16 (15.0) | 10 (4.3) |

| Respiratory disease§ | 15 (14.0) | 15 (6.5) |

| Other | 4 (3.8) | 12 (5.2) |

| Gastrointestinal disease§ | 2 (1.9) | 16 (6.9) |

| Osteoarticular disease§ | 4 (3.8) | 6 (2.6) |

| Endocrine or metabolic disease | 3 (2.8) | 8 (3.5) |

| Renal disease | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) |

Data are n (% of column) or median (IQR).

*Two or more comorbidities as recorded in the Charlson comorbidity index.

†Hospital admission(s) during the 6 months preceding index admission.

‡Including ischemic/thrombotic disorder, congestive heart failure and arrhythmia.

§Other than infection.

¶Including dementia, alcohol disorder and intoxication.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to the presence of 6 month death.

| Variable | 6 month death (n=31) | No 6 month death (n=331) |

| Age, years | 69 (64–80) | 74 (65–83) |

| Men | 15 (48.4) | 153 (49.8) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 10 (7–12) | 7 (5–9) |

| Multimorbidity* | 28 (90.3) | 274 (89.3) |

| Previous admission† | 17 (54.8) | 78 (25.4) |

| Duration of TUG test, seconds | 17 (11–21) | 12 (8–18) |

| TUG test duration ≥15 s | 18 (58.0) | 111 (36.2)‡ |

| Hospitalisation characteristics | ||

| Elective | 0 (0.0) | 13 (4.2) |

| Length of stay, days | 13 (6–27) | 6 (4–11) |

| Diagnosis of index admission | ||

| Cardiovascular disease‡ | 3 (9.7) | 88 (28.7) |

| Infection | 5 (16.1) | 62 (20.2) |

| Neuropsychiatric disease§, ¶ | 2 (6.5) | 63 (0.5) |

| Oncological disease | 12 (38.7) | 14 (4.6) |

| Respiratory disease§ | 1 (3.2) | 29 (9.5) |

| Other | 2 (6.5) | 14 (4.6) |

| Gastrointestinal disease§ | 4 (12.9) | 14 (4.6) |

| Osteoarticular disease§ | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.3) |

| Endocrine or metabolic disease | 1 (3.2) | 10 (3.3) |

| Renal disease§ | 1 (3.2) | 3 (1.0) |

Data are n (% of column) or median (IQR).

*Two or more comorbidities as recorded in the Charlson comorbidity index.

†Hospital admission(s) during the 6 months preceding index admission.

‡Including ischemic/thrombotic disorder, congestive heart failure and arrhythmia.

§Other than infection.

¶Including dementia, alcohol disorder and intoxication.

Functional impairment was associated with a higher risk of death within 6 months after discharge (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.15 to 5.18), while the risk of unplanned readmission was not significantly increased (OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.15). After adjusting for age and gender, the association was even stronger for death (OR 3.55, 95% CI 1.52 to 8.25), but it remained unchanged for unplanned readmission (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.64). We found no significant association between functional impairment and the absolute total number of unplanned readmissions within 6 months (unadjusted OR 1.34, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.15; adjusted OR 1.59, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.67). P-value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was >0.05 for both adjusted models, indicating good fit. The variance inflation factors and tolerance were near 1.00 for all variables, excluding significant collinearity. The link test confirmed that the linear approach to model the outcomes was correct.

In both sensitivity analyses including the eight patients with missing data for the TUG test, results remained similar, with a significant increased risk of death, but not of readmission: sensitivity analysis defining patients with missing data as functional impaired (TUG test duration ≥15 s): adjusted OR 3.57, 95% 1.57–8.08 for death, adjusted OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.92 for readmission; sensitivity analysis defining patients with missing data as non-functional impaired (TUG test duration <15 s): adjusted OR 2.93, 95% CI 1.31 to 6.56 for death, adjusted OR 1.43, 95% CI 0.86 to 2.37 for readmission. Results were similar in the sensitivity analyses setting the cut-off point at >10 or>20 s, respectively: OR 1.67 (95% CI 0.97 to 2.86) and 1.32 (95% CI 0.74 to 2.35) for readmission and OR 2.69 (95% CI 1.09 to 6.67) and 2.64 (95% CI 1.11 to 6.30) for death, as well as in the sensitivity analysis excluding 12 patients who were too debilitated to perform the TUG test (OR 4.16, 95% CI 1.76 to 9.83 for death; OR 1.50, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.55 for readmission).

Conclusion

In this prospective cohort study, we found that functional impairment, defined as ≥15 s to perform the validated performance-based ‘Timed Up and Go test’ before acute care hospital discharge, was associated with an almost 150% increase in the risk of death within 6 months after hospital discharge. Conversely, functional impairment was not associated with an increased risk of unplanned readmission.

These findings contrast with previous studies in which functional impairment was mostly positively associated with a higher risk of readmission.8–13 Several reasons may explain this difference.

First, we used the TUG test, which has been largely validated as a simple, quick and reliable clinical method to assess functional status,28 36–40 and presents several advantages in comparison with other tools to assess functional status. The TUG test is objective, and its very high inter-rater and test-retest reliability allows better comparability than other tools.28 40 41 Although this measure is very simple, it is actually constituted of several complex sequences (eg, moving from the sitting to the standing position), each of which evaluating multiple aspects needed for adequate functional status, including balance, mobility, cardiorespiratory function and coordination.42 It may therefore capture several factors such as disease severity, independently of the kind of disease, and may as such be a good proxy to predict overall health decline.6 7 Moreover, as opposed to other tools used to assess functional status,43–45 the TUG test does not suffer from ceiling or floor effects in healthy older adults.29 Furthermore, a physiotherapist is not absolutely needed, as it can be performed by nursing personal as well.46 47

Second, we included only patients discharged directly home or to a nursing home, while others focused on patients discharged to a rehabilitation care facility.8 Patients discharged to a rehabilitation clinic may be more functionally impaired and have a higher morbidity level than other patients at discharge from the acute care setting. Conversely, we can suppose that functional status will be improved by the rehabilitation stay, which may consequently lower the following risk of readmission or death. Similarly, other authors evaluated functional status at admission before an elective operation, at the time of discharge from the emergency department or 1 month after discharge.11 15 16 We may suppose that all those patients have a better functional status than our population, as the acute care hospitalisation may affect functional status, limiting comparability with our study.

Third, we focused on medical patients aged 50 years or older, while others studied older adults9–12 15 or patients with a specific disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or myocardial infarction.11 13 Fourth and finally, we included only unplanned readmissions, while many previous studies included elective readmissions in the primary outcome.8 10–14 16 Two other findings in our study support the absence of association between functional impairment and readmission. First, the number of hospitalisations in the 6 months following discharge was not significantly higher in the group of patients with functional impairment. Second, sensitivity analyses using other cut-off points to define functional impairment yielded similar results.

Interestingly, we found a significant association between functional impairment and death within 6 months after hospital discharge. Only few studies looked at this relationship between functional impairment and mortality following discharge.12 14 26 Two of them, which included 135 geriatric and 495 medical inpatients, respectively, were negative,14 26 while another study using the TUG test in 147 geriatric inpatients found an association.12 Our results are consistent with studies performed in ambulatory care settings.16–24 All these findings together support that functional impairment may rather be a predictor for mortality than for readmission.

If confirmed by larger studies in general medical inpatients, our findings may have two main clinical implications. First, it may help to identify high-risk patients who would most likely benefit from interventions that have been shown to improve functional status.10 48 However, further studies are needed to assess if these interventions can improve patients’ outcome also. Second, it may help clinicians to assess the risk of short-term death of their patients and to consequently tailor preventive and therapeutic care to each patient. Some drugs or preventive prescriptions, such as cancer screening, may indeed more harm than benefit to those high-risk patients unlikely to survive long enough to benefit from the intervention. The TUG test may, therefore, represent an easy-to-use and reliable tool for clinicians to improve assessment of patients’ life expectancy. As our results were similar when including or excluding patients who were too debilitated to perform the test, our findings may apply to those patients also, if classified as functionally impaired. Furthermore, our simple model adjusting only for age and gender lets suppose that other variables are not needed to predict the risk of death, which may be useful for clinical implementation.

Our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, our sample was relatively small. Second, the study was conducted in a single centre and included only medical patients, limiting the generalizability of our results; however, except for age, our population was otherwise unselected. Third, we excluded patients who were discharged to a rehabilitation facility because we hypothesised that their functional status at discharge of the acute care setting would not reflect their actual functional status at discharge of the rehabilitation clinic. Our findings may therefore not apply to these patients. Fourth, although we may not exclude residual confounding factors, the aim of our study was to evaluate the performance of the TUG test as a simple overall prediction measure and not as an independent risk factor. Therefore, we adjusted only for age and gender.

Our study has some strengths. First, we studied both readmissions and deaths, separately. Second, it was a prospective study with a long follow-up time of 6 months and no loss to follow-up during this whole period. Third, we included only unplanned readmissions. Fourth, we had no lost to follow-up, very few missing data, and in the sensitivity analyses including patients with missing data, excluding patients unable to perform the test or using other cut-off points to define functional impairment, results remained unchanged.

In conclusion, in this prospective cohort study, functional impairment was associated with an increased risk of death within 6 months after hospital discharge, but not with a significant risk of readmission. Simple performance-based assessment may represent a better prognostic measure for mortality than for readmission.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors had access to the data during the study. CEA takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and is the guarantor. Study concept and design: CEA, JDD, DH and MM. Acquisition of data: CEA, AF and MM. Analysis and interpretation of data: CEA and JDD. Drafting of the manuscript: CEA and JDD. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: DH, AF and MM.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Fribourg Cantonal Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unpublished data from the study.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. Owing to a scripting error, some of the publisher names in the references were replaced with 'BMJ Publishing Group'. This only affected the full text version, not the PDF. We have since corrected these errors and the correct publishers have been inserted into the references.

References

- 1. Donzé J, Aujesky D, Williams D, et al. . Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:632–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donzé J, Lipsitz S, Bates DW, et al. . Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2013;347:f7171 10.1136/bmj.f7171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–28. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Librero J, Peiró S, Ordiñana R. Chronic comorbidity and outcomes of hospital care: length of stay, mortality, and readmission at 30 and 365 days. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. . Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306:1688–98. 10.1001/jama.2011.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roedl KJ, Wilson LS, Fine J. A systematic review and comparison of functional assessments of community-dwelling elderly patients. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2016;28:160–9. 10.1002/2327-6924.12273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beauchet O, Fantino B, Allali G, et al. . Timed up and go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:933–8. 10.1007/s12603-011-0062-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burke RE, Whitfield EA, Hittle D, et al. . Hospital Readmission from Post-Acute Care Facilities: risk factors, timing, and outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:249–55. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tonkikh O, Shadmi E, Flaks-Manov N, et al. . Functional status before and during acute hospitalization and readmission risk identification. J Hosp Med 2016;11:636–41. 10.1002/jhm.2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peel NM, Navanathan S, Hubbard RE. Gait speed as a predictor of outcomes in post-acute transitional care for older people. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014;14:906–10. 10.1111/ggi.12191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson TN, Wu DS, Pointer L, et al. . Simple frailty score predicts postoperative complications across surgical specialties. Am J Surg 2013;206:544–50. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong RY, Miller WC. Adverse outcomes following hospitalization in acutely ill older patients. BMC Geriatr 2008;8:10 10.1186/1471-2318-8-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kon SS, Jones SE, Schofield SJ, et al. . Gait speed and readmission following hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of COPD: a prospective study. Thorax 2015;70:1131–7. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belga S, Majumdar SR, Kahlon S, et al. . Comparing three different measures of frailty in medical inpatients: multicenter prospective cohort study examining 30-day risk of readmission or death. J Hosp Med 2016;11:556–62. 10.1002/jhm.2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walker KJ, Bailey M, Bradshaw SJ, et al. . Timed up and go test is not useful as a discharge risk screening tool. Emerg Med Australas 2006;18:31–6. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00801.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dodson JA, Arnold SV, Gosch KL, et al. . Slow Gait speed and risk of mortality or hospital readmission after myocardial infarction in the translational research investigating underlying disparities in recovery from acute myocardial infarction: patients' Health Status Registry. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:596–601. 10.1111/jgs.14016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, et al. . Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;24:822–30. 10.1681/ASN.2012070702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tice JA, Kanaya A, Hue T, et al. . Risk factors for mortality in middle-aged women. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2469–77. 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bergland A, Jørgensen L, Emaus N, et al. . Mobility as a predictor of all-cause mortality in older men and women: 11.8 year follow-up in the Tromsø study. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:22 10.1186/s12913-016-1950-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antonini TC, de Paz JA, Ribeiro EE, et al. . Impact of functional determinants on 5.5-year mortality in Amazon riparian elderly. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2016;40:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Buyser SL, Petrovic M, Taes YE, et al. . Physical function measurements predict mortality in ambulatory older men. Eur J Clin Invest 2013;43:379–86. 10.1111/eci.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Idland G, Engedal K, Bergland A, et al. . And 13.5-year mortality in elderly women. Scandinavian journal of public health 2013;41:102–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. . Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011;305:50–8. 10.1001/jama.2010.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castro-Rodríguez M, Carnicero JA, Garcia-Garcia FJ, et al. . Frailty as a major factor in the increased risk of death and disability in older people with diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:949–55. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Castro-Rodríguez M, Carnicero JA, Garcia-Garcia FJ, et al. . Frailty as a major factor in the increased risk of death and disability in older people with diabetes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:949–55. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nikolaus T, Bach M, Oster P, et al. . Prospective value of self-report and performance-based tests of functional status for 18-month outcomes in elderly patients. Aging 1996;8:271–6. 10.1007/BF03339578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoeymans N, Wouters ER, Feskens EJ, et al. . Reproducibility of performance-based and self-reported measures of functional status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1997;52:M363–M368. 10.1093/gerona/52A.6.M363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed "Up & Go": a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Properties of the 'timed up and go' test: more than meets the eye. Gerontology 2011;57:203–10. 10.1159/000314963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zweig MH, Campbell G. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) plots: a fundamental evaluation tool in clinical medicine. Clin Chem 1993;39:561–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE. Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. New York: Wiley, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 34. DDamfglmPd P, University of Toronto. Goodness of link tests for generalized linear models. 29: Applied Statistics, 1980:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. . Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128–38. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sebastião E, Sandroff BM, Learmonth YC, et al. . Validity of the timed up and go test as a measure of functional mobility in persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:1072–7. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gautschi OP, Smoll NR, Corniola MV, et al. . Validity and reliability of a measurement of objective functional impairment in lumbar degenerative disc disease: the timed up and go (TUG) test. Neurosurgery 2016;79:270–8. 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berg KO, Maki BE, Williams JI, et al. . Clinical and laboratory measures of postural balance in an elderly population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992;73:1073–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Isles RC, Choy NL, Steer M, et al. . Normal values of balance tests in women aged 20-80. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1367–72. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shumway-Cook A, Brauer S, Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the timed up & go test. Phys Ther 2000;80:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steffen TM, Hacker TA, Mollinger L. Age- and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: six-minute walk test, Berg Balance Scale, timed up & go test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther 2002;82:128–37. 10.1093/ptj/82.2.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Janssen WG, Bussmann HB, Stam HJ. Determinants of the sit-to-stand movement: a review. Phys Ther 2002;82:866–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vereeck L, Wuyts F, Truijen S, et al. . Clinical assessment of balance: normative data, and gender and age effects. Int J Audiol 2008;47:67–75. 10.1080/14992020701689688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boulgarides LK, McGinty SM, Willett JA, et al. . Use of clinical and impairment-based tests to predict falls by community-dwelling older adults. Phys Ther 2003;83:328–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Garland SJ, Stevenson TJ, Ivanova T. Postural responses to unilateral arm perturbation in young, elderly, and hemiplegic subjects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1072–7. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mueller K, Hamilton G, Rodden B, et al. . Functional assessment and intervention by nursing assistants in hospice and palliative care inpatient care settings: a quality improvement pilot study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33:136–43. 10.1177/1049909114555397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Murphy K, Lowe S. Improving fall risk assessment in home care: interdisciplinary use of the timed up and go (TUG). Home Healthc Nurse 2013;31:389–96. 10.1097/NHH.0b013e3182977cdc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gu MO, Conn VS. Meta-analysis of the effects of exercise interventions on functional status in older adults. Res Nurs Health 2008;31:594–603. 10.1002/nur.20290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.