Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects more than 50% of critically ill patients. The formation of calcitriol, the active vitamin D metabolite, from the main inactive circulating form, 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), occurs primarily in the proximal renal tubules. This results in a theoretical basis for reduction in levels of calcitriol over the course of an AKI. Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in critically ill adults, and has been associated with increased rates of sepsis, longer hospital stays and increased mortality. The primary objective of this study is to perform serial measurements of 25(OH)D and calcitriol (1,25(OH)2D), as well as parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) levels, in critically ill adult patients with and without AKI, and to determine whether patients with AKI have significantly lower vitamin D metabolite concentrations. The secondary objectives are to describe dynamic changes in vitamin D metabolites, PTH and FGF23 during critical illness; to compare vitamin D metabolite concentrations in patients with AKI with and without renal replacement therapy; and to investigate whether there is an association between vitamin D status and outcomes.

Methods and analysis

230 general adult intensive care patients will be recruited. The AKI arm will include 115 critically ill patients with AKI Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome stage II or stage III. The comparison group will include 115 patients who require cardiovascular or respiratory support, but who do not have AKI. Serial measurements of vitamin D metabolites and associated hormones will be taken on prespecified days. Patients will be recruited from two large teaching Trusts in England. Data will be analysed using standard statistical methods.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained. Upon completion, the study team will submit the study report for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and for conference presentation.

Trial registration number

NCT02869919; Pre-results.

Keywords: adult intensive & critical care, vitamin D, acute renal failure

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Measurement of vitamin D concentrations and associated proteins over the course of critical illness in a non-interventional study.

Serial measurements will be undertaken to describe dynamic changes.

Inclusion of a heterogeneous intensive care unit patient cohort, including those receiving renal replacement therapy, with acute kidney injury of any aetiology.

Blood sampling is scheduled once per day on day 0, day 2, day 5 and at critical care discharge. As vitamin D levels have been found to vary over a 24-hour period, this may not fully describe vitamin D status.

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency is common, affecting 25% of the general UK adult population in summer and up to 30%–40% in winter months.1 There is increasing awareness that vitamin D deficiency is associated with a number of important health consequences. The role of vitamin D metabolites in calcium homeostasis and the regulation of bone metabolism is well characterised. In the last decade it has been recognised that vitamin D status also impacts on infectious, immunological, neurological, cardiovascular, endothelial and respiratory disorders.2–5 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, termed 25(OH)D, is the main circulating metabolite of vitamin D and serves as a marker for evaluation of vitamin D status.1 Generally, although not universally, accepted cut-offs for defining vitamin D deficiency and severe deficiency are 25(OH)D levels of 50 nmol/L and 30 nmol/L, respectively.2 5

Intensive care units (ICUs) worldwide have reported vitamin D deficiency rates ranging from 60% to 100%.5 The causes may predate admission, or be a consequence of critical illness, interventions or therapies.5 25(OH)D concentrations of <50 nmol/L are associated with an increased rate of sepsis, a longer length of hospital stay and increased mortality both in-hospital and at 30 days in this population.3 6–9 The role for supplementation remains unclear. The largest randomised controlled study found an in-hospital mortality benefit only in a predefined subgroup of participants with vitamin D concentrations of <30 nmol/L after administration of a high dose of enteral cholecalciferol.10

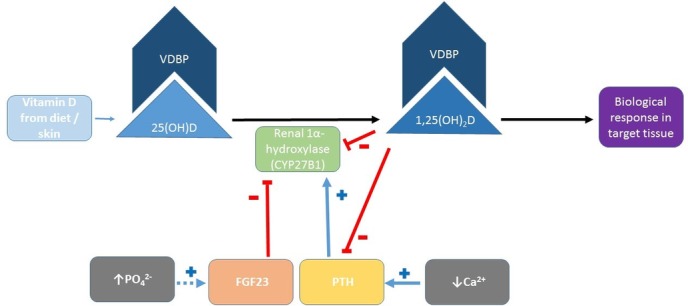

Availability of active vitamin D metabolites at tissue level depends mainly on the relationship between biologically inert 25(OH)D and the active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), as well as the actions of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), and the availability of vitamin D binding protein (VDBP).11 (figure 1) The biotransformation of 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D is regulated by the enzyme 1α-hydroxylase CYP27B1, which is produced primarily, but not exclusively, in the proximal renal tubules.1 Extrarenal autocrine and paracrine production of calcitriol by CYP27B1 is limited by substrate concentration,12 and as such may be diminished in deficiency states. VDBP is a 58 kDa protein produced by hepatic parenchymal cells, which transports vitamin D metabolites to target tissues and serves to increase the circulating half-life of vitamin D metabolites.1

Figure 1.

Outline of the conversion of inactive 25(OH)D to active 1,25(OH)2D by renal CYP27B1, and the influence of FGF23 and PTH. Extrarenal autocrine and paracrine production pathways are not shown. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; Ca2+, calcium; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; PO4 2−, phosphate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; VDBP, vitamin D binding protein.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) affects more than 50% of critically ill patients worldwide and is independently associated with higher mortality, a longer length of hospital stay, and an increased risk of long term complications including bone fractures.13 14 Furthermore, a single episode of AKI increases the long-term risk of recurrence of AKI. Compared with patients who do not have vitamin D deficiency, vitamin D-deficient critical care patients have been observed to have higher rates of AKI and more frequent need for renal replacement therapy (RRT),15 although any possible causal direction of this association remains unclear.

We hypothesise that patients with AKI have higher rates of vitamin D deficiency than those without AKI. If confirmed, our results may serve to inform the design of appropriate intervention trials in this patient group.

Rationale

Patients with AKI may have altered vitamin D metabolism mechanisms for reasons that could include the following:

The kidneys generate the majority of 1α-hydroxylase CYP27B1 and other hydroxylases implicated in vitamin D metabolism, and are responsible for producing and regulating 1,25(OH)2D and vitamin D-dependent proteins.10

FGF23 reduces circulating 1,25(OH)2D levels. Concentrations of FGF23 are elevated in AKI due to increased production by bone and reduced clearance.16 17

Patients with AKI have lower VDBP concentrations than patients without AKI.16

Pre-existing vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in the general population and has been associated with the development of AKI during critical illness.1 6 15

1,25(OH)2D has an elimination half-life of only 4–15 hours.1 Circulating levels may fall over the first days of critical illness if renal or extrarenal production capability is compromised.

Previous studies examining the association between AKI and vitamin D deficiency have been inconclusive. A study including 200 critically ill patients revealed significantly lower 1,25(OH)2D concentrations at the time of AKI diagnosis compared with controls without AKI, but there were no differences in 25(OH)D concentrations. PTH and FGF23 concentrations were not measured and serial measurements were not undertaken.8

A recent meta-analysis highlighted the lack of relevant studies that consider serial measurements of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D alongside other markers of vitamin D metabolism.3 Others have emphasised the importance of conducting intervention studies in the most appropriate cohort. Our aim is to understand the dynamic changes in vitamin D metabolite concentrations that occur over the course of AKI, from which the design of a future interventional study could be informed.

Objectives

The primary objective is to perform serial measurements of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D, PTH, FGF23 and VDBP concentrations in critically ill adult patients with and without AKI, to determine whether patients with AKI have significantly lower vitamin D metabolite concentrations.

The following are the secondary objectives:

to describe the changes of 25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D, PTH and FGF23 levels during critical illness

to compare total and bioavailable (ie, free plus albumin-bound, as opposed to that bound to VDBP; online supplementary appendix 1 18 19) concentrations of 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D in patients with AKI treated with and without RRT

to investigate whether there is an association between total and bioavailable vitamin D metabolite concentrations and outcome in critically ill patients with and without AKI; outcomes reported will be hospital mortality, 30-day mortality and length of stay in ICU and in hospital

to explore the possible statistical interaction between biomarker levels and length of ICU stay.

bmjopen-2017-016486supp001.pdf (199.7KB, pdf)

Methods and analysis

Setting

The study will be conducted in critical care units in two National Health Service hospitals in the UK.

Patient selection

Adult patients admitted to a critical care unit will be screened for the presence of AKI, on the basis of either serum creatinine or urine output, as defined by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO) consensus criteria (table 1).20 The critical care units are mixed medical and surgical.

Table 1.

KDIGO classification of AKI

| Stage | Serum creatinine (Cr) | Urine output |

| I | Rise of Cr by ≥26 µmol/L within 48 hours | <0.5 mL/kg/hour for more than 6 hours |

| Or 50%–99% Cr rise from baseline within 7 days (1.50–1.99 × baseline) | ||

| II | 100%–199% Cr rise from baseline within 7 days (2.00–2.99 × baseline) | <0.5 mL/kg/hour for more than 12 hours |

| III | ≥200% Cr rise from baseline within 7 days (≥3.00 × baseline) | <0.3 mL/kg/hour for 24 hours or anuria for 12 hours |

| Current Cr ≥354 µmol/L, with either rise of Cr by ≥26 µmol/L within 48 hours or ≥50% Cr rise from baseline within 7 days | ||

| Any requirement for renal replacement therapy |

AKI, acute kidney injury; KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome.

The following are the criteria for inclusion into the study: (1) adult patient (18 years or older) admitted to a critical care unit and (2) presence of KDIGO AKI II or III for ≤36 hours (AKI arm), or presence of cardiovascular and/or respiratory failure requiring the use of invasive or non-invasive respiratory support and/or treatment with catecholamines (non-AKI arm), with a requirement anticipated to last for longer than 24 hours.

The following are the exclusion criteria: (1) AKI stage I (as defined by KDIGO criteria), (2) known vitamin D deficiency (recorded value of <50 nmol/L on the hospital’s electronic record system, diagnosis documented on a hospital clinic letter, or evidence of vitamin D supplementation prescribed in primary or secondary care in the last 3 months), (3) known vitamin D supplementation in the last 3 months (either as a single agent or in a combination product, including multivitamins), (4) pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3b–5 (ie, estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL/min/1.73 m2), (5) renal transplant, (6) known hyperparathyroidism, (7) need for total parenteral nutrition (TPN), (8) anticipated life expectancy <48 hours, (9) haemoglobin concentration <70 g/L (unless a decision has been made to administer blood transfusion), and (10) pregnancy.

Sample size calculation

Based on data from Lai et al,8 126 patients with complete data are required to detect a difference of 25 pmol/L in 1,25(OH)2D concentrations between the two arms, with a power of 80% and at a two-tailed significance level of 5% (assuming an SD of 50 in each group). Interim review of the case report forms of a small set of patients highlighted an attrition rate of 40%–50% between the time of eligibility screening and day 5, leading to the requirement to recruit a total of 230 patients to analyse at least 126 with complete data.

Baseline data collection

The following data will be collected: age, gender, ethnicity, weight, height, ideal body weight, place of residence prior to hospitalisation, admission diagnosis, comorbidities (CKD, chronic lung disease, chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease, cancer, chronic liver disease, diabetes, chronic gastrointestinal disease), premorbid serum creatinine concentration, C reactive protein (CRP), albumin, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score on admission, and daily Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. We also plan to collect data on potential confounding factors, including daily nutritional intake, fluid balance, calcium and phosphate supplementation and treatment with extracorporeal therapy (ie, RRT and plasma exchange).

Sampling

On the day of enrolment, day 5 and the day of discharge from the critical care unit, blood will be taken for measurement of 25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D, PTH, FGF23 and VDBP. Samples will be taken in the morning, between 09:00 and 12:00. In a yellow top SST vacutainer, 5.5 mL of blood will be collected, and 4 mL will be collected in a purple top EDTA vacutainer. Samples will be centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min, then aliquots of 0.5 mL serum for 25(OH)D, 1 mL serum for 1,25(OH)2D and 0.5 mL serum for VDBP will be taken from the SST tube, and 1 mL of plasma for PTH and 1 mL of plasma for FGF23 from the EDTA tube. Samples will then be stored at −70°C until analysis. Additional measurements of 1,25(OH)2D and PTH will be made on day 2 (table 2). Calcium and phosphate are measured routinely on a daily basis for all ICU patients as part of preward round bloods, typically taken at 06:00. These results will be recorded.

Table 2.

Sampling schedule

| Serum concentration | Day 0 (day of enrolment) | Day 2 | Day 5 | Day of intensive care unit discharge |

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D | √ | – | √ | √ |

| 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Calcium (Ca) | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Phosphate (P) | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Parathyroid hormone | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Fibroblast growth factor 23 | √ | – | √ | √ |

| Vitamin D binding protein | √ | – | √ | √ |

All samples will be stored in dedicated research freezers until batch analysis.

25(OH)D will be measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, with a coefficient of variation of 7.3% for 25(OH)D2 and of 10.9% for 25(OH)D3. Total 1,25(OH)2D will be measured by radioimmunoassay. FGF23 will be measured using the Immutopics Human FGF23 (C-Term) ELISA assay.21 VDBP will be measured by ELISA assay, using the Quantikine Human Vitamin D BP Immunoassay.22 PTH will be measured using a Roche automated analyser.

Statistical analysis

Multiple comparisons will be performed to determine the difference in vitamin D metabolite concentrations between the two arms. The distribution of the data will be examined and appropriate statistical tests will be applied, accounting for potential confounding factors including age, ethnicity, CRP, calcium concentrations, season, severity of illness at admission using APACHE II scores and pattern of organ failures using SOFA scores. A longitudinal analysis will be presented, covering the time from enrolment to the date of critical care discharge, to describe changes in 25(OH)D, 1,25(OH)2D, FGF23 and PTH concentrations over the course of critical illness. An investigation of possible correlation between vitamin D metabolites and related hormones (PTH and FGF23) on day 0 and day 5 is planned. A subgroup analysis is planned for those participants receiving RRT and in patients with sepsis on the day of enrolment. Association between 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations and hospital and 30-day outcomes will be examined, as well as ICU and hospital length of stay.

An interim analysis is planned after recruitment of 126 participants.

Patients who do not have AKI at enrolment but who go on to develop AKI during the first 5 days will not be included in the analysis for the primary outcome. Results from these patients will be analysed separately.

Discussion

This study aims to describe the dynamic changes in 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D concentrations, and associated hormones, in a general population of critically unwell patients with and without AKI.

The strengths of this project are that (1) we plan to measure 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D together with regulatory hormones and proteins, which will address an existing gap in knowledge. (2) Serial measurements will be undertaken to determine dynamic changes, including an additional measurement of 1,25(OH)2D on day 2. This will serve to provide data on the timing and magnitude of a drop in concentrations of this metabolite, which is predicted based on previous work23 and from the biological basis that 1,25(OH)2D has a circulating half-life of only 4–15 hours.1 (3) The project is adequately powered to provide meaningful data.

We are aware of potential limitations, which we will eliminate as much as possible.

The high attrition rate identified in early work comprises participants who did not have AKI at enrolment, but who went on to develop AKI during the first 5 days of their critical care stay; patients who went on to meet an exclusion criterion such as requirement for TPN; and patients for whom a pre-existing known vitamin D deficiency was identified after enrolment. The sample size was increased to 230 to maintain power to detect a clinically significant difference between arms if one exists. The increase in sample size was approved by a national research ethics committee and the institutional governance department.

We plan to perform serial measurements but will only undertake blood sampling once a day. Blood samples will be collected in the morning (between 09:00 and 12:00) on the days specified in table 2. Previous studies confirmed diurnal variation of 25(OH)D concentrations in intensive care patients over 24 hours with mean within-patient variation of 24.3 nmol/L over a 24-hour period.24 As such, single point in time measures may not be adequate to describe vitamin D status fully.

We plan to enrol patients with AKI independent of underlying aetiology. By not stratifying patients by aetiology of AKI, patients with a wide range of clinical diagnoses will be eligible for inclusion and the results of the study will remain generalisable. Stratification would, nonetheless, have been useful to identify a population who may benefit most from supplementation in a future trial.

Patients prescribed vitamin D supplements in primary care or from secondary or tertiary care clinics at the host institutions can be identified and excluded from the study. However, patients taking vitamin D prescribed by other institutions or those buying over-the-counter supplements cannot be identified in all cases. Medication histories do routinely prompt for this, acknowledging that information from relatives in cases where the patient cannot clarify for themselves may be incomplete.

Limited resources mean measurement of other associated proteins, including alpha Klotho, which is primarily generated by the kidneys and plays a role in bone mineral metabolism, is not possible. Further, the lack of a standardised assay to measure circulating Klotho precludes its measurement within this study.25 It could, however, represent an interesting area for future work.

The equations used to describe levels of bioavailable vitamin D metabolites (ie, free and albumin-bound; online supplementary appendix 1) have not been validated in the critical care population, but have been used in several other studies that included critical care patients.2 3 26 27 The bioavailable vitamin D values reported in this study should be viewed as indicative estimates, as direct assay of free vitamin D metabolites is not possible. While measurement of concentration of VDBP to inform the equations in online supplementary appendix 1 is possible within the available resources, assessment of genotype is not. Lack of this information, which is known to affect the affinity of vitamin D metabolites for VDBP, is a limitation of this work.28

Ethics and dissemination

Full ethical approval was granted by the London — Camberwell St Giles National Research Ethics Committee on 30 March 2016.

Participants will be asked to give their consent to participate in the study. In the event that they are unable to give consent for themselves, a personal consultee (eg, next of kin) will be contacted and informed about the study and asked whether the patient would have any objections to participating in this observational study. They will be asked to sign a personal consultee declaration form. In case a personal consultee is not available, a nominated consultee (a clinician who is not connected to the research study) will be contacted. When the patient regains capacity, they will be informed about the study and asked to give consent to remain in the study. The Research Ethics Committee agreed that the study has the potential to benefit participants lacking capacity without imposing a disproportionate burden on them.

On completion, the study team will submit the study report for publication in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LKC is a coinvestigator of the study and was involved in the design of the study protocol. She wrote the first draft of the manuscript, designed the case report form and is the primary data collector at the lead site. She revised the manuscript in response to suggestions by all authors and the reviewers, and approved and submitted the final draft. KL, SS, NLD, KF, NP, JS, KC, FK and NGK are research coordinators and have a crucial role in the conduct of the study in all participating sites. They were involved in the design of the protocol, revised the manuscript and approved the final draft. JFD and LGF are the lead investigators in one of the participating sites. They made contributions to the study protocol, revised the manuscript and approved the final draft. DH advised on the laboratory measurements of vitamin D and related substances. He contributed to the study protocol and the first draft of the manuscript, revised subsequent drafts and approved the final version. GH is a consultant in clinical chemistry and advised on the laboratory measurements of vitamin D and related hormones. She contributed to the study protocol and the first draft of the manuscript, revised subsequent drafts and approved the final version. MO is the chief investigator of the study. She developed the study and wrote the main study protocol. She is overseeing the project and revised several drafts of the manuscript before approving the final version. All authors approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by research funding from Fresenius Medical Care. The sponsor was not involved in the design of the protocol and has no involvement in the conduct of the study. The results will remain intellectual property of the research team. LKC’s involvement was supported by the Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: London — Camberwell St Giles Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Public Health England. Vitamin D and Health;2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-vitamin-d-and-health-report. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holick MF. Medical Progress vitamin D deficiency. New Engl J Med 2007;357:266–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Haan K, Groeneveld AB, de Geus HR, et al. . Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for infection, Sepsis and mortality in the critically ill: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2014;18:660 10.1186/s13054-014-0660-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, et al. . Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amrein K, Christopher KB, McNally JD. Understanding vitamin D deficiency in intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1961–4. 10.1007/s00134-015-3937-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braun A, Chang D, Mahadevappa K, et al. . Association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and mortality in the critically ill. Crit Care Med 2011;39:671–7. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206ccdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zittermann A, Schleithoff SS, Frisch S, Gotting C, et al. . Circulating calcitriol concentrations and total mortality. Clin Chem 2009;55:1163–70. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.120006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lai L, Qian J, Yang Y, et al. . Is the serum vitamin D level at the time of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury diagnosis associated with prognosis? PLoS One 2013;8:e64964 10.1371/journal.pone.0064964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C, Mullie P, et al. . Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:76–89. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amrein K, Schnedl C, Holl A, et al. . Effect of high-dose vitamin D3 on hospital length of stay in critically ill patients with vitamin D deficiency: the VITdAL-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:1520–30. 10.1001/jama.2014.13204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hiemstra TF. Vitamin D in renal disease. Br J Ren Med 2012;17:23–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E, et al. ; Am J renal physiol. 289, 2005:F8–F28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, et al. . Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1411–23. 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang WJ, Chao CT, Huang YC, et al. . The impact of acute kidney injury with temporary Dialysis on the risk of fracture. J Bone Miner Res 2014;29:676–84. 10.1002/jbmr.2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ala-Kokko TI, Mutt SJ, Nisula S, et al. . Vitamin D deficiency at admission is not associated with 90-day mortality in patients with severe Sepsis or septic shock: observational FINNAKI cohort study. Ann Med 2016;48:67–75. 10.3109/07853890.2015.1134807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leaf DE, Wolf M, Waikar SS, et al. . FGF-23 levels in patients with AKI and risk of adverse outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7:1217–23. 10.2215/CJN.00550112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Christov M, Waikar SS, Pereira RC, et al. . Plasma FGF23 levels increase rapidly after acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2013;84:776–85. 10.1038/ki.2013.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bikle DD, Siiteri PK, Ryzen E, et al. . Serum protein binding of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: a reevaluation by direct measurement of free metabolite levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1985;61:969–75. 10.1210/jcem-61-5-969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bikle DD, Gee E, Halloran B, et al. . Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;63:954–9. 10.1210/jcem-63-4-954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. KDIGO AKI Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Immutopics® Human FGF-23 (C-Term) ELISA KIT 2 nd Generation Enzyme-LinkedImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) for the detection of Human Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Levels inPlasma or Cell Culture Media. Immutopics Inc. San; Clemente, CA. http://www.immutopics.com/pdf/directional-inserts/60-6100r08.pdf (accessed Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22. https://resources.rndsystems.com/pdfs/datasheets/dvdbp0.pdf. Quantikine® ELISA human vitamin D BP immunoassay. Abingdon UK: (accessed Apr 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leaf DE, Waikar SS, Wolf M, et al. . Dysregulated mineral metabolism in patients with acute kidney injury and risk of adverse outcomes. Clin Endocrinol 2013;79:491–8. 10.1111/cen.12172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Venkatesh B, Davidson B, Robinson K, et al. . Do random estimations of vitamin D3 and parathyroid hormone reflect the 24-h profile in the critically ill? Intensive Care Med 2012;38:177–9. 10.1007/s00134-011-2415-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neyra JA, Hu MC, M c H. Potential application of klotho in human chronic kidney disease. Bone 2017;100 http://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bone.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Quraishi SA, Bittner EA, Blum L, et al. . Prospective study of vitamin D status at initiation of care in critically ill surgical patients and risk of 90-day mortality. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1365–71. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quraishi SA, De Pascale G, Needleman JS, et al. . Effect of Cholecalciferol Supplementation on vitamin D status and cathelicidin levels in Sepsis: a randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1928–37. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chun RF, Peercy BE, Adams JS, et al. . Vitamin D binding protein and monocyte response to 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D: analysis by mathematical modeling. PLoS One 2012;7:e30773 10.1371/journal.pone.0030773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016486supp001.pdf (199.7KB, pdf)