Abstract

Objectives

Interpretation of CIs in randomised clinical trials (RCTs) with treatment effects that are not statistically significant can distinguish between results that are ‘negative’ (the data are not consistent with a clinically meaningful treatment effect) or ‘inconclusive’ (the data remain consistent with the possibility of a clinically meaningful treatment effect). This interpretation is important to ensure that potentially beneficial treatments are not prematurely abandoned in future research or clinical practice based on invalid conclusions.

Design

Systematic review of RCT reports published in 2014 in Annals of Internal Medicine, New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, JAMA Internal Medicine and The Lancet (n=247).

Results

85 of 99 articles with statistically non-significant results reported CIs for the treatment effect. Only 17 of those 99 articles interpreted the CI. Of the 22 articles in which CIs indicated an inconclusive result, only four acknowledged that the study could not rule out a clinically meaningful treatment effect.

Conclusions

Interpretation of CIs is important but occurs infrequently in study reports of trials with treatment effects that are not statistically significant. Increased author interpretation of CIs could improve application of RCT results. Reporting recommendations are provided.

Keywords: clinical trials, clinical trial interpretation, reporting

Strength and limitations of this study.

Systematic review, including randomised clinical trials published in six high-impact medical journals.

Recommendations for reporting and interpreting CIs are provided.

Our interpretation of the CIs was based on the author-specified clinically relevant treatment effect or the treatment effect used in the sample size calculation. We did not attempt to evaluate the validity of these interpretations.

Introduction

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of medical treatments. However, when a statistically significant treatment effect is not demonstrated (ie, the p value for the primary analysis is not less than or equal to the prespecified significance level), the estimate of the treatment effect and the p value alone does not allow the reader of an RCT report to distinguish between the following two possibilities: (1) the treatment does not have a clinically meaningful effect or (2) the study is unable to rule out a clinically meaningful treatment effect with a high degree of confidence (ie, the results of the trial would best be described as ‘inconclusive’).1–6 However, trials for which the effect of treatment on the primary outcome variable is not statistically significant have often been called ‘negative’ and presented as though they support the conclusion that the experimental treatment lacks efficacy.3 This can result in premature abandonment of potentially beneficial treatments clinically and in future research programmes.

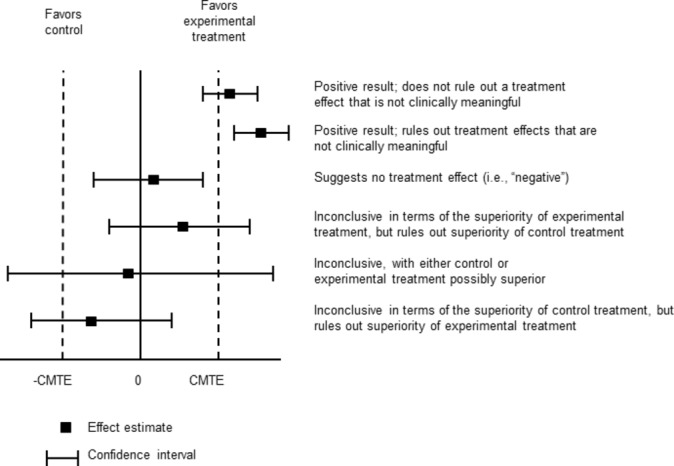

For decades, biostatisticians and others have encouraged the use of CIs as a means to present the range of treatment effects consistent with the observed data and to evaluate whether RCT results that are not statistically significant suggest that the experimental treatment is ineffective or instead that the trial results are inconclusive (figure 1).1–6 Inconclusive results should not be used to inform clinical practice or treatment guidelines.

Figure 1.

Using CIs to interpret results of randomised clinical trials. Note that a value of zero indicates no treatment effect in this case; in other cases such as when the treatment effect is quantified using, for example, an OR, HR or relative risk, a value of 1 would indicate no treatment effect. Adapted from Senn.23 CMTE, clinically meaningful treatment effect.

Previous reviews have assessed CI reporting in publications of preclinical and clinical studies within specific medical specialties.7–14 To our knowledge, no reviews have examined CI reporting and interpretation in RCTs published in high-impact general medical journals.

Methods

Data sources and searches

RCTs published in 2014 in Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal, Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), JAMA Internal Medicine, The Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine were identified using PubMed (online supplementary appendix 1). The year 2014 was selected to evaluate the most recent reporting practices at the time the project was initiated. Relevant articles were identified following PRISMA guidelines.

bmjopen-2017-017288supp001.pdf (136.8KB, pdf)

Study selection

Selected articles were primary reports of RCTs that compared the efficacy of at least two treatments (one of which could be a placebo, active comparator or a wait-list control) using frequentist inferential methods. Trials not evaluating treatments were excluded (eg, comparison of two cancer screening techniques or the effect of two imaging techniques on surgical decision-making). Trials using a non-inferiority or super superiority design were excluded because CIs are interpreted differently for these trials than for standard superiority trials. Dose-finding studies, studies declared to be exploratory in nature, studies focused on safety and cluster-randomised studies were also excluded. Two authors (RAK and JSG) independently screened all identified articles to determine whether they met the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A coding manual was developed to evaluate the frequency with which CIs were reported for the treatment effects in RCTs (online supplementary appendix 2). In the subset of articles that reported results that were not statistically significant for the primary outcome measure, coders were asked to evaluate whether the CI for the treatment effect indicated that the data were consistent with the absence of a clinically relevant treatment effect or that the results were inconclusive (ie, the coders compared the CI for the treatment effect with a clinically relevant treatment effect declared by the authors at any point in the manuscript or the treatment effect specified in the sample size calculation if no clinically relevant treatment effect was described by the authors). A treatment effect was considered not statistically significant if the associated p value was greater than 0.05 unless a different significance criterion was specified by the authors. Articles were excluded from this subset if they reported results that were both significant and non-significant for the primary outcome measure (ie, when multiple analyses were reported for the primary outcome measure). Articles were, however, included in this subset even if they reported a statistically significant treatment effect in a subgroup analysis or in analyses that were identified as sensitivity analyses because these analyses were considered secondary.

bmjopen-2017-017288supp002.pdf (215.2KB, pdf)

For the comparison of the CI with the author-declared clinically meaningful treatment effect or the effect size used in the sample size calculation, the coders considered the primary analysis if one was identified. If a primary analysis was not identified, the coders considered the first analysis of a primary outcome measure that was reported by the authors. Coders also recorded whether the authors used the CI to interpret any results that were not statistically significant. The coding manual was pretested and modified for clarity and content by JSG and RAK in five rounds of three articles each using RCTs published in 2013 that otherwise met the eligibility criteria.

In some cases, the absolute or relative differences in event rates to be detected between groups were reported in the sample size calculation and the results concerning the treatment effect were presented as either a hazard ratio (HR), odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR). In these cases, JSG attempted to convert the information provided in the sample size calculation to either the HR, OR or RR, as appropriate, using some combination of the following: absolute risk reduction (p0–p1), RR reduction ((p0–p1)/p0), assumed event rate in the control group (p0) and assumed event rate in the treatment group (p1). The following formulas were used: HR=ln(1–p1)/ln(1–p0), OR=(p1(1–p0))/(p0(1–p1)) and RR=p1/p0. Such calculations were used to determine ratios representing the clinically relevant treatment effect for 26 articles. Note that the HR calculation yields an estimate that assumes an exponential distribution for the event times.

The data were extracted from each article independently by two authors (RAK coded all articles and JSG and JGK each coded approximately half). RAK reviewed the data for discrepancies and fixed obvious oversights. JSG reviewed any discrepancies due to interpretation and made the final decision on their resolution. JSG also reviewed the final data relating to interpretation of CIs in all of the relevant articles to ensure accuracy.

Results

Trial characteristics

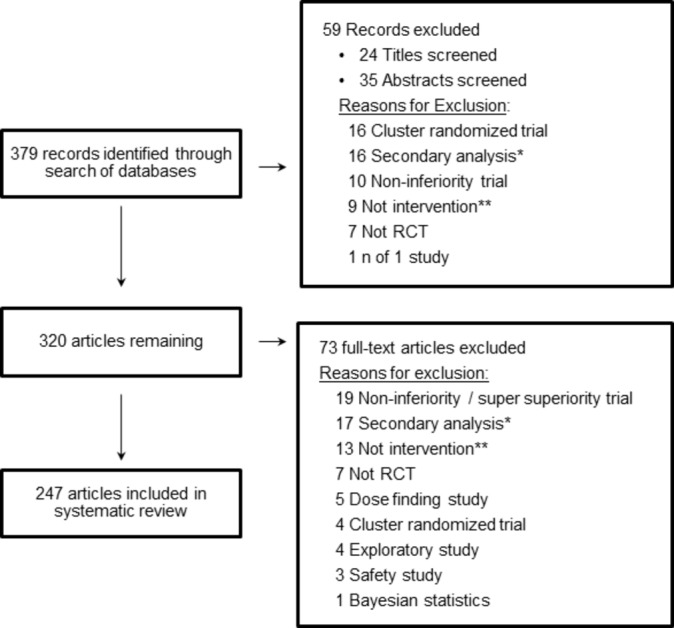

The final sample included 247 articles (figure 2). Trial characteristics are presented in table 1. The articles covered a range of medical specialties; the most common were cardiovascular (22%), infectious disease (15%) and cancer (13%). A little over half of the trials were sponsored, at least in part, by industry (54%).

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram randomised clinical trial (RCT). *Secondary analysis of data from a previously reported trial. **RCT examines efficacy of something other than a medical or lifestyle intervention (eg, a cancer screening method or a diagnostic decision-making tool).

Table 1.

Trial characteristics

| Characteristic | All articles (n=247) | Articles reporting a treatment effect (TE) that was not statistically significant, the CI of the TE and a value for the TE that the authors considered to be clinically meaningful (n=78) |

| Journal | ||

| New England Journal of Medicine | 105 (43%) | 31 (40%) |

| JAMA | 61 (25%) | 22 (28%) |

| The Lancet | 50 (20%) | 11 (14%) |

| British Medical Journal | 13 (5%) | 8 (10%) |

| JAMA Internal Medicine | 11 (4%) | 1 (1%) |

| Annals of Internal Medicine | 7 (3%) | 5 (6%) |

| Design | ||

| Parallel group | 245 (99%) | 78 (100%) |

| Cross-over | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Number randomised | 480 (224–1195) | 730 (311–1880) |

| Medical specialty | ||

| Cardiovascular | 55 (22%) | 23 (29%) |

| Infectious disease | 38 (15%) | 12 (15%) |

| Cancer | 31 (13%) | 4 (5%) |

| Neurology (including pain) | 22 (9%) | 7 (9%) |

| Pulmonary | 13 (5%) | 6 (8%) |

| Psychiatry | 12 (5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Other* | 76 (31%) | 25 (32%) |

| Type of intervention | ||

| Treatment | 183 (74%) | 52 (67%) |

| Prevention | 64 (26%) | 26 (33%) |

| Sponsor | ||

| Industry | 134 (54%) | 36 (46%) |

| Other | 113 (46%) | 42 (54%) |

Values are n (%) or median (IQR).

*Other includes areas represented by fewer than 10 trials including urology, orthopaedics, diabetes, immune disorders and so on.

CI reporting

Of the 247 included articles, 99 did not report any statistically significant treatment effects on the primary outcome measure. Of those 99, 85 (86%) reported the CI for the treatment effect. Of the 14 articles that did not report the CI for the treatment effect, 6 (42%) reported the CI for the parameter estimate (eg, mean, event rate) for each group separately. The percentage of articles that reported a CI for the treatment effect in the whole sample (n=247) was similar (85%).

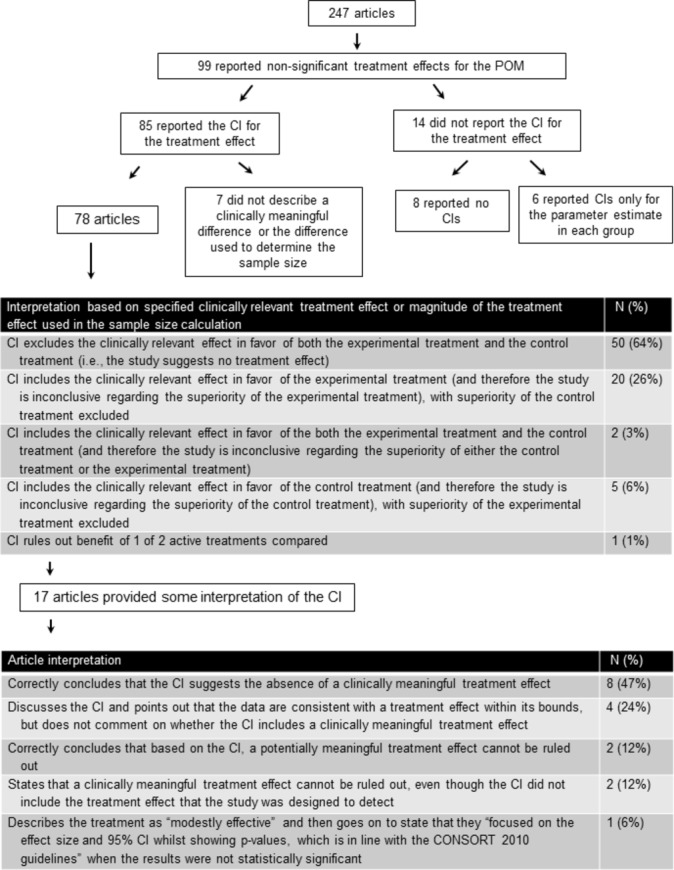

Within the 85 articles mentioned above, an additional 7 articles did not report the magnitude of the treatment effect used to estimate the sample size of the study or specify what they would consider to be a clinically relevant treatment effect, leaving 78 articles for whcih we could interpret the CIs. Of those 78 articles, 18 specified a clinically relevant treatment effect (six identified this as a minimal clinically meaningful or important treatment effect; 12 identified this as a clinically meaningful, relevant, significant, important or worthwhile treatment effect) and in the other 60 articles, we interpreted the trial results based on the treatment effect used to estimate the sample size. We interpreted the non-significant results most commonly as falling into two categories: (1) the CI excluded the treatment effect used for the sample size calculation or the author-specified clinically relevant effect (ie, the data were consistent with no clinically relevant treatment effect) (n=50, 64%) and (2) the CI included the treatment effect used for the sample size calculation or the author-specified clinically relevant effect in favour of the experimental treatment only (ie, the data could not rule out a clinically meaningful effect of the experimental treatment) (n=20, 26%) (figures 1 and 3).

Figure 3.

CI reporting and interpretation. POM, primary outcome measure.

Of the 99 articles, 82 (83%) with statistically non-significant results did not provide any interpretation of the treatment effect using CIs. The number of articles that provided an interpretation of the CI for each journal is provided in online supplementary table 1. In the 17 (17%) articles that did provide an interpretation of the treatment effect using CIs, the interpretations were of five types: (1) consistent with our interpretation, the authors stated that the CI suggested the absence of a clinically meaningful effect (n=8); (2) the authors highlighted the possible treatment effects that were consistent with the CI, but did not speculate on whether those effect sizes were clinically meaningful (n=4); (3) similar to our conclusions, the authors concluded that based on the CI, a clinically meaningful treatment effect could not be ruled out (n=2); (4) the authors conservatively stated that they could not rule out clinically meaningful treatment effects even though the CI excluded the effect size that the trial was designed to detect (n=2) and (5) the authors described the treatment as ‘modestly effective’ and then went on to state that they ‘focused on the effect size and 95% CI while showing p values, which is in line with the CONSORT 2010 guidelines’ when the results were not statistically significant (n=1). We interpreted this trial’s results to be inconclusive (figure 3).

bmjopen-2017-017288supp003.pdf (157.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

Consistent with widespread recommendations,1–6 we found that the 85% of articles reporting RCTs published in six high-impact medical journals in 2014 reported the CIs for the treatment effect. The percentage of articles that reported CIs in our review was higher than the percentage of articles that reported CIs in previous reviews of RCTs in specialty journals (85% in our review versus 5% to 66% in previous reviews).7–14 This increase could be due to the earlier publication periods covered by the previous reviews (ie, 1990–2008). It could also be due to the fact that the six journals included in our review require adherence to the CONSORT guidelines,15 which promote transparent reporting, for publication of RCTs. Regardless of whether the increased reporting of CIs that we observed is in fact due to an effect of time or of the specific journals selected, our results suggest that relatively high-quality reporting is possible when required by guidelines, reviewers and/or editors.

Although reporting CIs provides the reader the ability to make a judgement regarding whether the results are ‘negative’ or ‘inconclusive’, such interpretations require an understanding of CIs and knowledge of what should be considered a minimal clinically meaningful treatment effect with respect to the outcome variable used in the trial. Because it cannot be assumed that all readers and stakeholders will have this expertise or necessarily agree on this point, best reporting practices should include careful interpretation of the CIs and their implications for the conclusions of the trial.

The percentage of articles in our sample that interpreted CIs was much lower than the percentage that simply reported them. Only 17 of the 99 articles that reported analyses of a primary outcome measure that were not statistically significant used a CI to (1) highlight the range of values of the treatment effect that were consistent with the data or (2) discuss whether the trial results were inconclusive or were consistent with the absence of a clinically meaningful treatment effect. Additionally, although the CIs of 22 articles included the treatment effect used for the sample size calculation or the author-specified clinically relevant treatment effect, only 4 of these articles stated that the study could not rule out a clinically meaningful treatment effect. Our data suggest that many authors do not discuss that the results of their trial can be considered inconclusive on the basis of the CIs they report, perhaps because they believe that doing so might decrease the perceived importance of the RCT. Acknowledging that the study cannot rule out a clinically meaningful effect is important to ensure that clinicians, policy-makers and payers do not inappropriately use the trial results as evidence to suggest that the treatment is ineffective.

It must be acknowledged, of course, that the magnitude of a treatment effect that would be considered clinically meaningful can differ depending on many factors, including the setting of the trial and perspective of the reader.16–19 For example, if a treatment has very few side effects or no treatments currently exist for the condition, the minimal clinically meaningful treatment effect is likely to be relatively small compared with a treatment with greater safety risk. This may be especially true from an individual patient’s perspective. On the other hand, the minimal clinically meaningful treatment effect may be larger from a funder or researcher’s perspective when considering whether to support or pursue a line of research. It is important that these potential differences in perspective are acknowledged when interpreting CIs and that the authors present the rationale for the minimal clinically meaningful treatment effect that they used to interpret the results of the trial.

Another method that is sometimes used to interpret the results of RCTs is to present a post hoc power calculation. As many authors have correctly argued, however, such a calculation is irrelevant to trial interpretation.20–22 Encouragingly, only three of the included articles with treatment effects on the primary outcome measures that were not statistically significant reported a post hoc power calculation. Three other articles stated that the trials had adequate power without any apparent justification. Post hoc power calculations should be avoided and interpretations regarding whether a trial is ‘negative’ or ‘inconclusive’ would be better based on CIs.

Interestingly, 8% of the 247 included articles reported a CI for the parameter of interest for each separate treatment group (eg, mean or event rate), but not for the between-group treatment effect. It is important to emphasise that CIs for the parameters of individual treatment groups are not informative with respect to evaluating whether the results of a trial with a statistically non-significant treatment effect are ‘negative’ as opposed to ‘inconclusive’.

A limitation of our review is that we based our interpretation of the CIs reported in the studies with statistically non-significant treatment effects on the author-specified clinically relevant treatment effect or the magnitude of the treatment effect used in the sample size calculation. We did not attempt to evaluate the validity of these values as being of clinical importance because our intention was to evaluate the frequency with which authors used CIs in the interpretation of trial results and whether these interpretations were consistent with their assumptions regarding clinically meaningful treatment effects. Furthermore, the treatment effects used to determine the sample size of a trial are not necessarily what one would consider to be the minimal clinically meaningful treatment effect that investigators might still be pleased to demonstrate.23 For example, investigators may justify the sample size using a larger effect than would be considered minimally clinically meaningful if an effect of this magnitude were anticipated based on existing data.

It would have been interesting to determine whether the articles that concluded that the trials were ‘negative’ without consideration of CIs actually reported CIs that did not exclude the clinically relevant treatment effect. Unfortunately, we were unable to categorise articles as claiming that the trial was ‘negative’ because authors often had contradictory statements throughout the discussion regarding whether the ‘negative’ conclusion was definitive. These inconsistencies highlight the importance of using CIs to interpret whether a trial with a treatment effect that is not statistically significant is ‘negative’ or ‘inconclusive’.

In conclusion, the majority of the trials we reviewed reported the CI for the treatment effect, demonstrating relatively high-quality, transparent reporting of RCT results. In contrast, a substantially smaller percentage of articles reporting analyses of the primary outcome measure that were not statistically significant discussed the implications of the CIs of the treatment effect when interpreting the results of their study. We encourage all authors and reviewers to prioritise interpretation of RCT findings using CIs, especially when the CIs indicate that the data cannot rule out a clinically meaningful treatment effect (box 1). We also encourage readers to consider the CIs when applying the results of RCTs with non-significant results to their clinical practice or research programme.

Box 1. CI reporting recommendations for RCTs with statistically non-significant results.

Report CIs for the treatment effect.

Discuss interpretation of the CI regarding the magnitude of effects that can be ruled out with reasonable confidence.

Discuss whether the results suggest a ‘negative’ or ‘inconclusive’ result.

Acknowledge any uncertainty regarding what is considered a clinically meaningful treatment effect on the outcome measure used in the trial.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Stephen Senn for his thoughtful review and comments on our manuscript. This article was reviewed and approved by the Executive Committee of the ACTTION public–private partnership with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JSG contributed to the design of the review and coding. She performed the analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and incorporated coauthor revisions. RHD, MPM, SRE, RAG, JDM and DCT contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the results and provided feedback on the manuscript. RAK, JC and JGK contributed to coding for the systematic review and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: Financial support for this project was provided by the Analgesic, Anaesthetic and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks (ACTTION) public–private partnership, which has received research contracts, grants or other revenue from the FDA, multiple pharmaceutical and device companies and other sources.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the FDA or the pharmaceutical and device companies that provided unrestricted grants to support the activities of the ACTTION public–private partnership should be inferred.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Alderson P. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ 2004;328:476–7. 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ 1995;311:485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Freiman JA, Chalmers TC, Smith H, et al. . The importance of beta, the type II error and sample size in the design and interpretation of the randomized control trial. survey of 71 "negative" trials. N Engl J Med 1978;299:690–4. 10.1056/NEJM197809282991304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gardner MJ, Altman DG. CIs rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J 1986;292:746–50. 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rothman KJ. A show of confidence. N Engl J Med 1978;299:1362–3. 10.1056/NEJM197812142992410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simon R. Confidence intervals for reporting results of clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 1986;105:429–35. 10.7326/0003-4819-105-3-429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anttila H, Malmivaara A, Kunz R, et al. . Quality of reporting of randomized, controlled trials in cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2006;117:2222–30. 10.1542/peds.2005-1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fan FF, Xu Q, Sun Q, et al. . Assessment of the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials on treatment of coronary heart disease with traditional chinese medicine from the chinese journal of integrated traditional and western medicine: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e86360 10.1371/journal.pone.0086360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kiehna EN, Starke RM, Pouratian N, et al. . Standards for reporting randomized controlled trials in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg 2011;114:280–5. 10.3171/2010.8.JNS091770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kloukos D, Papageorgiou SN, Fleming PS, et al. . Reporting of statistical results in prosthodontic and implantology journals: p values or confidence intervals? Int J Prosthodont 2014;27:427–32. 10.11607/ijp.4011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Naunheim MR, Walcott BP, Nahed BV, et al. . The quality of randomized controlled trial reporting in spine literature. Spine 2011;36:1326–30. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f2aef0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Polychronopoulou A, Pandis N, Eliades T. Appropriateness of reporting statistical results in orthodontics: the dominance of P values over confidence intervals. Eur J Orthod 2011;33:22–5. 10.1093/ejo/cjq025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Urbanic JJ, Lee WR. Confidence intervals and survival estimates: a systematic review of 3 oncology journals. Am J Clin Oncol 2006;29:405–7. 10.1097/01.coc.0000227525.96972.2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang P, Xu Q, Sun Q, et al. . Assessment of the reporting quality of randomized controlled trials on the treatment of diabetes mellitus with traditional chinese medicine: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e70586 10.1371/journal.pone.0070586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, et al. . Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: immpact recommendations. Pain 2009;146:238–44. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guyatt GH, Juniper EF, Walter SD, et al. . Interpreting treatment effects in randomised trials. BMJ 1998;316:690–3. 10.1136/bmj.316.7132.690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kraemer HC, Morgan GA, Leech NL, et al. . Measures of clinical significance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:1524–9. 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruyssen-Witrand A, Tubach F, Ravaud P. Systematic review reveals heterogeneity in definition of a clinically relevant difference in pain. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:463–70. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodman SN, Berlin JA. The use of predicted confidence intervals when planning experiments and the misuse of power when interpreting results. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:200–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-121-3-199408010-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenland S. Nonsignificance plus high power does not imply support for the null over the alternative. Ann Epidemiol 2012;22:364–8. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. An abuse of power: ther pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat 2001;55:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Senn SJ. Statistical issues in Drug Development. 2nd edition West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017288supp001.pdf (136.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017288supp002.pdf (215.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017288supp003.pdf (157.8KB, pdf)