Abstract

Introduction

Many individuals suffer from chronic pain or functional somatic syndromes and face boundaries for diminishing functional limitations by means of biopsychosocial interventions. Serious gaming could complement multidisciplinary interventions through enjoyment and independent accessibility. A study protocol is presented for studying whether, how, for which patients and under what circumstances, serious gaming improves patient health outcomes during regular multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

Methods and analysis

A mixed-methods design is described that prioritises a two-armed naturalistic quasi-experiment. An experimental group is composed of patients who follow serious gaming during an outpatient multidisciplinary programme at two sites of a Dutch rehabilitation centre. Control group patients follow the same programme without serious gaming in two similar sites. Multivariate mixed-modelling analysis is planned for assessing how much variance in 250 patient records of routinely monitored pain intensity, pain coping and cognition, fatigue and psychopathology outcomes is attributable to serious gaming. Embedded qualitative methods include unobtrusive collection and analyses of stakeholder focus group interviews, participant feedback and semistructured patient interviews. Process analyses are carried out by a systematic approach of mixing qualitative and quantitative methods at various stages of the research.

Ethics and dissemination

The Ethics Committee of the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioural Sciences approved the research after reviewing the protocol for the protection of patients’ interests in conformity to the letter and rationale of the applicable laws and research practice (EC 2016.25t). Findings will be presented in research articles and international scientific conferences.

Trial registration number

A prospective research protocol for the naturalistic quasi-experimental outcome evaluation was entered in the Dutch trial register (registration number: NTR6020; Pre-results).

Keywords: Chronic pain, functional somatic syndrome, serious gaming, multidisciplinary rehabilitation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The novelty of the intervention and study methods is a strength.

Using a pragmatic approach to study serious gaming when deployed in a regular healthcare setting enables to understand under what conditions serious gaming will (not) work.

Study limitations come with the naturalistic design, due to pragmatic reasons, that prevents random treatment assignment and stringent diagnostic methods.

Introduction

Background and rationale

Video games are vividly debated to their behavioural and clinical outcomes, which may be negative or positive depending on game content and player attributes.1 2 Serious (health) games primarily target promotion of health benefits.3 A new serious game, called LAKA, aims to facilitate patient learning about living with complex chronic somatic complaints.4 Based on the results of a feasibility study, LAKA is deployed in a regular healthcare setting, as an additional component of outpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation. The current protocol presents an innovative mixed-methods study for gaining insight into the effectiveness of serious gaming as a complementary modality during regular multidisciplinary rehabilitation.

Using a variety of definitions and measures of pain and disability, the worldwide prevalence estimates for chronic pain range between 7% and 64%.5–9 Individuals are in chronic pain (CP) when complaints persist beyond the usual 3 to 6 months of organic recovery.10 Functional somatic syndromes (FSS) are diagnosed in individuals that seek medical help for functional disturbance and chronic somatic symptoms without a satisfactory explanation by organ pathology or disease.11 CP and FSS may have a biological explanation in central nervous system sensitisation.12 13 Predisposition to these disorders is probably determined by a combination of genetic factors and personality characteristics.14 15 Symptom patterns are often precipitated by trauma or social factors.16–18 Maladaptive thoughts, feelings and behaviour are assumed to maintain the symptoms.17 19–21 Regarding treatment, support has been found for a stepped care approach with active biopsychosocial treatment when monodisciplinary treatments are insufficient.17Randomised controlled trials that compared symptoms and functioning after multidisciplinary rehabilitation versus alternative treatments in patients with CP or chronic fatigue syndrome generally reported up to medium-sized differences.22–25 Nonetheless, recent research addresses improvement of biopsychosocial intervention models,26 27 ‘matching’ and ‘blending’ therapeutic strategies and delivery modes28 29 and promotion of patient engagement.30 As such, access, reach, adherence and effectiveness of biopsychosocial interventions may be enhanced.

Serious gaming could be of aid here. Previously investigated strategies are ‘exergaming’ to improve motivation for physical activity,31 ‘brain training games’ against dullness in the remediation of cognitive functions,32 ‘virtual reality’ for safety in graded activity or exposure33 and ‘health behaviour gaming’ for fun while addressing behavioural antecedents.3 In the fields of rehabilitation and pain management, virtual environments have shown promise in reducing acute pain by distraction, or in activity management to restore physical functioning.34 35 Despite of promising results for various monodisciplinary applications of gaming and simulation, no evident application seems to exist for supporting biopsychosocial adjustment processes in patients with CP or FSS.2 3 32–37 Outcome improvement after treatment in patients with CP or FSS may be mediated by changes in aspects of self (beliefs about illness and fear avoidance, catastrophising and psychological flexibility), coping behaviour and affect.38 39 Features that distinguish serious games from traditional modes include covert learning techniques, interactivity, storytelling, sound effects, visuals and ‘debriefings’. They could offer relative benefits for behavioural change processes through distinctive attentional (presence), affective (enjoyment) and metacognitive processes.40–43 Further research into gaming mechanisms is needed42 and may also inform about how biopsychosocial intervention mechanisms could be strengthened.

However, within the outcome evaluation of multidisciplinary interventions several complicating factors arise. These consist of outcome multidimensionality and dependency on implementation in actual healthcare settings.44 45 In other words, characteristics at the levels of organisation, care providers, patients and interventions all affect outcome levels.46 47 Therefore, ideally, multiple sources of information are used to evaluate to what extent, for whom, when and under what circumstances an innovation of multidisciplinary treatment improves outcomes in patients with CP or FSS.48 49 For example, some intervention studies show different outcomes of a computer-delivered therapy when applied in different countries.50 This is also an important issue for the outcomes of serious gaming, which are clearly sensitive to context factors.51 52 Therefore, ‘debriefings’ are suggested as a method for discussing and exploiting game–play experiences and strengthening learning outcomes.53 Previous studies leave uncertainties about how to effectively organise instructional support, that is, via software or delivered by (trained) healthcare staff, via internet or face-to-face, in groups or individually. There is strong consensus that adequately powered clinical trials are needed to determine the effectiveness of serious gaming.2 3 37 Moreover, pragmatic trials and realist evaluation principles are needed to determine how serious gaming relates to patient outcomes depending on how it is deployed in actual healthcare settings.

Study aims

Here we describe the protocol for outcome and process evaluations of complementary serious gaming during regular multidisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with CP or FSS, which holds three study aims. The first aim is to investigate the effectiveness of serious gaming as a treatment complement. We question to what extent multidisciplinary rehabilitation with an additional serious gaming component is more effective than multidisciplinary rehabilitation without serious gaming for symptom reduction and clinically relevant improvement. Primarily, interdependent outcome domains of pain, fatigue and emotional functioning (pain intensity, pain coping and cognition, fatigue complaints and psychological distress) are studied, because they are considered to be relevant and plausible for the intervention and population.27 45 Secondary outcomes are patients’ impression of overall improvement, general subjective health and satisfaction with functioning and treatment.

Second, we aim to understand which innovation, patient, provider and organisation level factors influence the outcomes of serious gaming for patients. Innovation level factors could be design quality and compatibility with user routines. Patient level facilitators or barriers could be demographic, health status and intervention history factors. Serious gaming outcomes could also depend on complex provider behaviour by attitude, skill and/or time constraints. Finally, outcomes of serious gaming could be influenced by its organisation in a clinical setting. Therefore, we pose the question: what are the barriers and facilitators of outcome improvement through serious gaming according to patients, providers and other stakeholders? Furthermore, we question how variation in serious gaming outcomes can be decomposed with plausible patient level differences and/or delivery conditions within the treatment setting (ie, size of a debriefing group).

The third aim concerns how serious gaming contributes to patient outcomes. For this, we explore various serious gaming mechanisms, being the subjective experiences and objective performances in context that may affect health outcomes. In addition, plausible linear effects between mechanisms and patient outcome variables are investigated. Achievement of all three research aims will inform the further development of a valid and practical programme theory of serious gaming outcomes in regular healthcare for patients with CP or FSS.

Methods and analysis

Study design and procedure

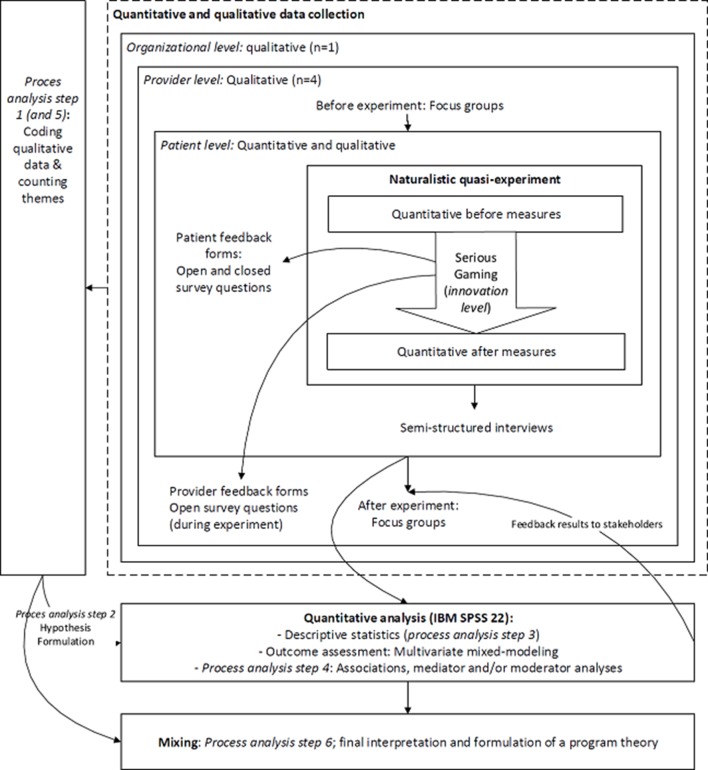

An embedded experimental mixed-methods design is created by an integrated multidisciplinary research team (MV, HV, MJ, AZ, AM) to address all three research aims in a single study (see figure 1). For studying the first research aim, which is to estimate patient level outcome improvement due to serious gaming during regular outpatient rehabilitation, a two-armed naturalistic quasi-experiment is prioritised (displayed at the centre of figure 1). A serious gaming intervention is deployed for usage by all patients, at two sites of a Dutch outpatient rehabilitation clinic. Therefore, an intervention group is constituted of patients who receive the multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme with an additional serious gaming intervention. The control group consists of patients who simultaneously follow the same programme in two similar sites of the same clinic without serious gaming. Codified quantitative data from patient records will be retrieved and analysed to examine between group outcome differences. The protocol for the naturalistic quasi-experiment was entered in the Dutch trial register (NTR6020).

Figure 1.

Overview of the mixed-methods design.

Embedding qualitative methods before, concurrently to and after the quasi-experiment suits our second and third study aims. This mixed-method design is ideal for examining intervention processes, understanding mechanisms related to variables and supporting programme theory development.54 Herein, no intermediate qualitative results are communicated with providers and implementers during the experiment. Data collection started in April 2016 and is planned to end in March 2017, quantitative outcome data will be retrieved when concurrently collected qualitative data are analysed (February 2017).

Recruitment

Sites and professionals

Two intervention sites where serious gaming is deployed participate in the study. For the recruitment of control subjects, two other sites (out of 18 sites as part of the same treatment centre) are selected based on similarity with regard to patient characteristics, facilities, protocols, history, personnel, location in or near a city in the southern Netherlands, and no other research projects planned during the intervention period. The treatment centre provides rehabilitation care covered by health insurance in association with a university medical centre. Professional study participants are local stakeholders of serious gaming, including experts, implementers and providers.

Patients

Patient candidates received an indication of eligibility for outpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation from a rehabilitation physician and completed half of their rehabilitation programme at a participating site. Physician indications of eligibility are followed, which are based on the results of diagnostic surveys, physical and psychological investigations and clinical interviewing. Accordingly, patient participant inclusion criteria are: being between 18 and 67 years of age, reporting the presence of pain for more than 6 months or fatigue complaints or a musculoskeletal disease for more than 3 months, having no (more) indication for another (cost-) effective medical treatment and have concomitant psychosocial problems. Patients are excluded from participation if: psychiatric symptoms are not adequately controlled, there is significant risk of psychological decompensation through a rehabilitation treatment, language or communication problems make it impossible to follow rehabilitation and/or demonstrable inability to change behaviour (due to personality disorders, third party liabilities or otherwise). An information letter, consent form and verbal explanation are provided by local care providers. The recruitment process is monitored to ensure that all candidates are invited.

Interventions

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme

The outpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme includes common biopsychosocial approaches and incorporates a focus on well-being and participation.26 The standardised 16-week programme consists of on average 95 hours of individual or group sessions that are organised in modules and centrally assigned to individual patients based on diagnostic findings. Each patient is treated by a team of two physiotherapists and two registered master’s degree psychologists. Psychotherapeutic techniques include cognitive behavioural therapy and psychodynamic approaches. For all patients, treatment contains rationales, goal setting and feedback, social support, exposure treatment, behavioural repetition and substitution, skills training (in relaxation, social skills and meditation) and identity development techniques. Allocation of physical therapy, cognitive restructuring, eye movement desensitisation and an intensive 2-day well-being course depend on diagnostic findings for physical status, psychopathological symptoms55 and fear avoidance beliefs,56 post-traumatic stress and psychological well-being.

Serious gaming

Theory and change techniques of the serious game LAKA

Developer assumptions for the game LAKA have been documented throughout development and related to conceptual frameworks (see appendix).57 Serious gaming is proposed to promote practice for well-being improvement and for identifying and diminishing distortions and biases of self. This may be helpful for patients with CP or FSS in reducing the burden of their symptoms.58 Based on a review of information about the design rationale, functionality, validity proof (before outcome evaluation) and data protection measures of LAKA, an independent jury awarded three out of five attainable stars for quality (see appendix).59

The serious game LAKA promotes practice through an Avatar model. Before the game starts, participants are invited to identify with an Avatar of their chosen gender and name (table 1). The storyline introduces an Avatar who recently experienced physical and social deterioration, senses an urgency to change and engages in a trip around the world to learn about ‘the art of living’. Player tasks are: to explore and select virtual action plans for ‘encounters’ with non-playing characters, to evaluate their ‘satisfaction’ about chosen actions and to perform skills training in focused attention and open-monitoring meditation exercises.60 Encounter scenarios model uncertain events resulting in varying Avatar states depending on action plans chosen by players. Encounters are increasingly influenced by distant cultural meanings to challenge anticipation of the course of events (eg, depending on the scenario, agreeable responding can result in a pleasant interaction or involvement in a scam). Players receive global feedback on the extent to which chosen actions correspond with a reference model for values (see appendix). Self-reflective elements are interspersed with short casual action and puzzle games, images and information associated with the location of the Avatar. These features are included to vary game play, and can be skipped.

Table 1.

Features, dose and tasks

| Features | Dose (in game frequency) | Tasks |

| Introduction | 1 | —Choose Avatar gender and name —Receive instruction: to identify with the personal Avatar —Introduction to Avatar storyline —Receive task instructions from LAKA (non-playing character with a mentoring role) |

| Encounters (see online supplementary appendix 1) for screenshot and user interface) |

16 | —Select action plans for the Avatar in encounters with non-playing characters (each instance offers five optional action plans, which are modelled after a reference set of values: generosity, moral discipline, patience, enthusiastic perseverance). |

| Mood scenarios | 8 | —Select action plans for the Avatar when subjected to an adverse event. —Given the adverse scenario: think of what your own affective state would be in this situation and bear in mind the depicted emotional state of the Avatar. |

| Reflections | 4 | —Assess satisfaction about selected Avatar actions on a scale of 0–10. —Receive feedback from LAKA on chosen action plans. —Receive feedback about the correspondence between satisfaction rating and LAKA assessment. |

| Attention training | 3 | —Guided (focused attention and open-monitoring) meditation exercises for mental stability. |

| Tours | 16 | —Skip or listen to ‘tour-guide’ voice-overs informing about pictures of the location visited by the Avatar. |

| Loading screens | - | —See where travel destinations are located on a geographical map. |

| Mini games | 8 | —Action games: steering a vehicle (by using tilt mechanism of tablet pc or keyboard arrow controls) to arrive at the next encounter (reference: ‘rocket bird’). —Puzzle: fix a road by connecting parts of the road to arrive at the next encounter (reference: ‘plumber games’). |

| Festive closing | 1 | —Replay of ‘extreme’ responses throughout the game. |

bmjopen-2017-016394supp001.pdf (400.8KB, pdf)

Mode of delivery

In accordance with patient suggestions for optimal reach, the rehabilitation clinic delivers professional assistance and the occasion for playing the serious game LAKA on site, besides downloading and playing on a home computer.4 Suitable rooms with Wi-Fi connection, tablet computers with LAKA installed and headphones are provided. Four 1-hour sessions of serious gaming are planned for one to six patients simultaneously during weeks 9–12 of their rehabilitation programme. The sessions are scheduled in connection with other therapy sessions to ease coordination with daily activities. Staff members are available for consultation on accessing serious gaming (ie, for technical issues and adaptation to special needs). Experienced therapists (one physiotherapist, and three psychologists) facilitate the first session (introduce LAKA and instruct to complete the game independently during sessions 2 and 3) and the fourth session (debriefing). The goal of the debriefings is to discuss experiences of game play, technology acceptance and learning transfer to daily life. For external validity, no specific roles were assigned to other local stakeholders for the delivery of serious gaming (ie, to observe ‘natural’ problem solving by implementers).

Programme theory

The framework of context, mechanism, outcome (CMO) configurations is used to structure ongoing development of a programme theory for serious gaming as a complement during multidisciplinary rehabilitation.61 To illustrate, a patient with an active coping style self-exposed for a short amount of time to unsupported serious gaming during multidisciplinary rehabilitation (context), experienced enjoyment and discrepancy regarding valued self-identities (mechanism) and expected this to contribute to health improvement (outcome).4 Timely building blocks for CMO configurations for serious gaming are deduced from the literature. Besides by symptom categorisation, serious gaming outcomes were interpreted by frameworks of rehabilitation mechanisms as self-improvements (see online supplementary appendix 1).27 45 57 58 62 63 Two comprehensive implementation models are used for the classification of context factors, such as planning and compatibility relative to other treatment components.64 65 Finally, mechanisms of serious gaming are discerned as gaming behaviours (frequency, length and performance of game play) and user experiences of gaming, simulation and information systems. More specifically, subjective mechanisms may involve sense of presence,66 technology acceptance,67 positive and negative affect,68 game-based learning69 and perceived ‘learning transfer’ to daily life.53

Measures

Quantitative data

Outcome and case-mix variables are retrieved from routinely administered clinical patient records after all participants have completed their rehabilitation programme. All patient variables are collected by the clinic through a standardised and secured web-surveying procedure, including facilitation of patients without convenient computer access and promotion of follow-up completion.4 70 Outcomes are monitored at the indication of eligibility (at baseline), after 8 weeks of treatment (intermediate) and again after 16 weeks of treatment (post). Relevant and valid measures were available for assessing the primary outcomes (see table 2). These endpoints include a numerical rating scale for current pain intensity,71 the pain coping and cognitions list,72 fatigue as assessed by the Checklist Individual Strength63 and psychopathological symptoms as measured by the Symptom Checklist.55 Secondary measures focus on clinical relevance, such as patients’ global impression of improvement after treatment.45 Another widely used single item Likert scale rating is used for measuring general health (poor to excellent).73 Finally, numerical rating scale items are available to assess patients’ satisfaction about treatment and functioning (see table 2).

Table 2.

Quantitative outcome measures

| Variables | Measures | Time of measurement |

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Current pain intensity | 1-item Numerical Rating Scale 0–10 | Baseline, intermediate, post-treatment |

| Pain coping and cognition | Pain Coping and Cognitions List | |

| Fatigue | Checklist Individual Strength | |

| Psychopathological symptoms | Symptom Check List | |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Clinically relevant improvement | Patient Global Impression of Change | Intermediate, post-treatment |

| General subjective health | “What do you think of your current health in general?” | |

| Perceived functioning | “Please indicate how satisfied you are with your current level of functioning.” | |

| Treatment satisfaction | Three Likert scale items, that is, “Would you recommend this treatment centre to other rehabilitation patients?” | Post-treatment |

Patient variables are demographic, health status and treatment history information (see table 3).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Variables (measurement) |

| Age | Years of age (calculated from registered date of birth) |

| Gender | % Female |

| Socioeconomic status | Highest education level, source of income (categorical rating items) |

| Coping style | Utrecht Coping List81 (validated questionnaire) |

| Environment | Presence of problems with regard to social life, financial situation, trauma, work situation (categorical rating items) |

| Symptoms | Duration (months; calculated from the date of onset), course (categorical rating item) and pain location (standard physical examination report) |

| Physical status | Body mass index, blood pressure, musculoskeletal conditions (standard physical examination report) |

| Other treatment | (Changes of) presence of medication usage, frequency of healthcare visits, previous visits to health providers (medical specialists, physiotherapists and/or psychologist) (categorical rating items) |

| Treatment (modules) received | Automatic logs of session presence (determined from absence registrations by healthcare providers) |

Intervention mechanisms may cover subjective experiences and objective behaviours of serious gaming (see table 4). Automatic registrations in patient files enable objective assessment of serious gaming frequency, duration, progress and performance. Moreover, a short survey was composed in collaboration with the rehabilitation centre to measure subjective experiences shortly after serious gaming. This survey contains items on perceptions of using a serious game (regarding usefulness, ease of use, trust, enjoyment, goal clarity, challenge and learning4 67 69), the 10-item short form of the positive and negative affect scale,74 the involvement and realism scales from the Igroup Presence Questionnaire66 and (0–10) numerical rating scale item on perceived learning transfer. A reminder was sent to intervention group participants if the survey was not completed within a week after their last gaming session. Finally, a questionnaire on patient values may be used to explore relationships between mechanisms and outcomes of serious gaming.

Table 4.

Quantitative indicators for mechanisms

| Variables | Measures | Respondents | Time of measurement |

| Reach, dose, gaming performance | Data logs: frequency, timing, length, progress and scores of play | Intervention group | During serious gaming (automatic) |

| Acceptability and playability | Selection of UTAUT2* items (perceived usefulness, ease of use, trust, enjoyment) Selection of EGameFlow items (clear goals, challenge, perceived learning) |

Intervention group | Post-serious gaming |

| Positive and negative affect | PANAS-SF | Intervention group | Post-serious gaming |

| Presence (general, involvement and realism) | IGroup Sense of Presence Questionnaire item for general sense of presence and subscales for involvement and realism. | Intervention group | Post-serious gaming |

| Learning transfer | Numerical rating scale (0–10): “Use the following slider to indicate to what extent you expect that the LAKA sessions contribute to your daily life”. | Intervention group | Post-serious gaming |

| Values (expressed in thoughts and behaviour) | Values questionnaire†: 5-point Likert scales, that is, “If I find it necessary, I'll intervene to help or to protect others”. | Intervention and control groups | Baseline, intermediate, post-treatment |

*Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology.

†Psychometric properties are still under investigation. Empirical support for good scale internal consistency and strong associations with psychological well-being in rehabilitating patients were documented in a report for the Dutch Committee on Test Affairs (COTAN).

PANAS-SF, Positive and Negative Affect Scale—Short Form.

Qualitative data

Protocols for focus group and semistructured patient interviews are informed by the CMO building blocks and principles for interviewing in realist evaluation.75 Accordingly, the interviewer starts with an open and explorative style, but may sometimes take an explanatory role to raise discussion about programme theory elements when CMO configurations become better delineated. Providers are expected to be especially knowledgeable about context and mechanisms of serious gaming, while patients may say the most about context and outcomes. Purposive sampling of participants is used until reaching a point of data saturation. All interviews are tape recorded and verbatim transcribed. Transcripts and a summary of findings are sent to participants by e-mail to enable them to check if their views are accurately reflected.

Stakeholder (focus group) interviewing

Four focus group interviews are held, two before and two after the naturalistic experiment, to involve stakeholders in the ongoing development of serious gaming and programme theory. Participant selection and topics are based on actual data needs. Heterogeneous groups of care providers, implementers and experts (in information and communication technology, well-being and serious gaming) are invited for the first and last discussion meetings. The first interview focused on the research goals for an open discussion. The last group interview will focus on programme theory for member checking and refinement. Homogenous groups of provider participants may be invited for the second and third focus groups for more in-depth information. Provider participants are asked to share positive and/or negative feedback about serious gaming via a secured web form. This includes information on the occurrence and management of adverse events and/or unintended effects during serious gaming.

Patient interviewing

Two open interview questions about gaming experience and perceived learning transfer are added to the postgaming survey for intervention group participants. Patient participants with high and low scores on a 1-item numerical rating scale (0–10) for perceived learning transfer are invited for a semistructured interview after their rehabilitation treatment. These interviewees are asked to describe their health outcomes during rehabilitation and to list the three most important reasons why serious gaming did, or did not, contribute positively or negatively to this process. A point of saturation is reached if the three factors (context and/or mechanisms) mentioned are all richly described. Control group interviewees are matched to some of the intervention group interviewees to compare rehabilitation outcome changes for similar cases with versus without serious gaming.

Analysis

Statistical outcome evaluation

Quantitative data will be imported in SPSS V.22, described after statistical inferences and analysed on intention-to-treat basis. All case-mix variables are described for individual study participants, as well as the differences between intervention group and control group participants. Multivariate mixed-linear modelling techniques will be used to evaluate the extent to which serious gaming predicts variance in patient outcome levels between the intermediate and final outcome assessments of the rehabilitation programme. Effective sample size and intraclass coefficients will be calculated to determine dependency on hierarchical patterns in outcome variation by care provider levels. An optimal prediction model will be specified, correcting for potential unbalances between the study groups (at baseline and/or intermediate) and/or important higher level random effects.

Process analyses

A programme theory will be created after a sequence of analysis steps. In each step, analyses will be performed completely by MV and in part by MJ or AZ (independent coding of interviews and rerunning syntax), and discussions will be held involving a third author (HV) to resolve differences and find agreement about the results. First, concurrently collected qualitative data analyses will be performed to identify plausible CMO configurations from the perspectives stakeholders. All qualitative data will be coded in vivo and higher order coded using CMO building blocks to determine configurations. Second, a selection of key CMO configurations will be made based on counts of the number of participants supporting them in their open text responses to the postgaming survey. Hypotheses will contain specific expectations of (linear) relationships implied by the CMOs. If needed, additional provider or site level data (ie, debriefing session group sizes) will be retrieved from clinical administration records. Third, quantitative data will be screened by testing internal consistency in SPSS or data triangulation with qualitative data if possible. Fourth, hypotheses will be tested with available and valid quantitative data. Fifth, data from the last focus group will be coded. Sixth, quantitative and qualitative findings will be mixed for an overall interpretation and drawing final conclusions.

Power calculation

From practical, theoretical and statistical perspectives, a powerful primary outcome assessment was anticipated by focusing on recruiting a sufficient number of individual patients from the four participating treatment facilities. The rehabilitation centre (n=1), intervention sites (n=2), as well as the number of time-points (3), are practically fixed. Analysis of unpublished pilot data suggested that variation in baseline to post-treatment outcome changes between treatment locations might be negligible relative to individual variation within sites (intraclass correlations <0.05).

G*Power was used for sample-size calculations.76 A required sample size of 212 participants was calculated for determining a small to medium effect by means of a multivariate analysis of variance test of global effects. Effect size estimation was based on meta-analysis results for the effects of serious games on cognition, motivation and psychological outcomes.3 The following parameters were inserted: for power (1-Beta)=0.8; effect-size f2(V)=0.0625; type 2 error probability (alpha)=0.05; number of dependent variables=5; and number of groups=2. By the same standards, it was checked if the determined sample size would also be sufficient for independent univariate tests of variance on each of the primary outcomes.

Anticipating some level dependence and/or randomly missing data (pain coping and cognition measures are not filled out by patients reporting 0 pain intensity at baseline), 250 patient participants will be recruited. Assuming 20% treatment and study attrition rates and an average weekly inflow of nine patients starting with their treatment within each of the four facilities, outcome data are available 6 months after recruiting the first patient.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for the mixed-methods protocol was obtained from the psychological ethics committee of Tilburg School of Social and Behavioural Sciences (EC-2016.25t). In the absence of a legal obligation for medical ethics review, independent judgement was provided on the protection of patient rights by conformity to the letter and rationale of the applicable laws and research practice. Patient participants are consented before participation, that is before receiving the additional (5–10 min) survey (intervention group), being invited for a semistructured interview or retrieving their codified data. Participants were protected against harm by regular clinical safety measures throughout. Professional participants are also consented before participation in qualitative data collections. Under supervision of MJ, MV is responsible for safe storage and the accessibility of (codified) research data to all authors. Qualitative and quantitative results will be presented and discussed together in one or more research article(s) and at one or more international scientific conferences. A summary of study results will be provided to the study participants.

Discussion

The novelty of the serious gaming intervention and study methods are strengths of the proposed evaluation but imply limitations as well. LAKA is the first serious game that promotes practice for self-process enhancement under highly prevalent adverse conditions such as CP or FSS. CMO configurations may be identified that are transferable to other populations and settings where similar approaches to behavioural change are beneficial.77 However, internal and external validity are threatened due to divergence from the golden standard procedures of a (cluster) randomised controlled (multicentre) trial. Instead, pragmatic considerations for the deployment of serious gaming during rehabilitation in two sites of a single Dutch centre led treatment allocation, recruitment and data collection methods. Different comparisons with serious gaming (ie, usual care, waiting list or text-based computer-based intervention), more elaborate diagnostic assessment and outcome measurements including role participation and long-term follow-up are precluded. Still, conditional optimisation of quasi-experimental methods is a legitimate strategy for obtaining evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention.78 Apparent confounding factors (ie, differences in usual treatment received) should be controlled for by appropriate methods. By the emergence of practical limitations, study strengths shift towards dealing with questions of process. The realist evaluation principles and mixed-methods used in this study are increasingly accepted in scientific communities as means to compensate for practical limitations and to build programme theories that enhance future predictions of intervention effects across patients and healthcare settings.

Legitimate application of mixed methods is promoted by the protocol in various ways. First, participant recruitment and selection methods for quantitative and qualitative examinations allow a strong representation of patients receiving biopsychosocial treatment in a regular outpatient setting. This differs from studies in which the eligibility of applicants for computer-based intervention depends on motivation and/or ability to use a computer or internet facilities.79 80 Second, perspectives of insiders (patients, healthcare providers and developers) and outsiders (independent experts and members of the research team) will be used. Third, relevant theoretical constructs are specified before quantitative and qualitative data collections to prevent process analysis results being strongly affected by the sequencing of qualitative and quantitative methods. Fourth, predefined steps structure data convergence and switches in epistemological paradigms when qualitative methods are used to propose quantitative results (in advance) and to explain them (afterwards).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: Acknowledged for their role in the development of serious gaming are: Ciran (owner and developer): Alfonsus van Bergen, Jan Jochijms and Jeroen van Bergen. Software developers: Paladin Studios, Marcel Lips. Contributors of intellectual content: Tibetan Institute Yeunten Ling, Karel Michiels and Jac Geurts.

Contributors: MV, HV, AM, and MJ conceived the protocol. MV drafted the work, which was critically revisited by HV, AZ, AM and MJ for important intellectual content. All authors have given their final approval of the version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The work was supported by Ciran in the development of LAKA, allocation of serious gaming and provision of raw quantitative data. Ciran is a foundation that develops and provides a rehabilitation care programme for complex chronic pain and fatigue symptoms in association with Radboud Academic Medical Centre (The Netherlands). Qualitative data collection, data management, data analyses, interpretation of results, writing of the report and publication decisions are authorised by university staff members.

Competing interests: MAPV reports employment by Ciran and is provided time and occasion to conduct independent doctoral research by way of agreement at Tranzo, Scientific Centre for Care and Welfare, Tilburg University. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed and approved by Tranzo in accordance with its policy on objectivity in research. HJMV reports personal fees from Ciran, outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. Owing to a scripting error, some of the publisher names in the references were replaced with 'BMJ Publishing Group'. This only affected the full text version, not the PDF. We have since corrected these errors and the correct publishers have been inserted into the references.

References

- 1. Gentile DA, Anderson CA, Yukawa S, et al. . The effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behaviors: international evidence from correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2009;35:752–63. 10.1177/0146167209333045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Primack BA, Carroll MV, McNamara M, et al. . Role of video games in improving health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:630–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeSmet A, Van Ryckeghem D, Compernolle S, et al. . A meta-analysis of serious digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion. Prev Med 2014;69:95–107. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vugts MA, Joosen MC, van Bergen AH, et al. . Feasibility of applied gaming during interdisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with complex chronic pain and fatigue complaints: a mixed-methods study. JMIR Serious Games 2016;4:e2 10.2196/games.5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. . Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–87. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy J, Roll JM, Schraudner T, et al. . Prevalence of persistent pain in the U.S. adult population: new data from the 2010 national health interview survey. J Pain 2014;15:979–84. 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, et al. . Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010364 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, et al. . Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan: a second survey of people with or without chronic pain. J Orthop Sci 2014;19:339–50. 10.1007/s00776-013-0525-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Häuser W, Wolfe F, Henningsen P, et al. . Untying chronic pain: prevalence and societal burden of chronic pain stages in the general population - a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14:352 10.1186/1471-2458-14-352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, et al. . The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull 2007;133:581–624. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harvey SB, Wessely S. How should functional somatic syndromes be diagnosed? Int J Behav Med 2013;20:239–41. 10.1007/s12529-013-9300-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meeus M, Nijs J. Central sensitization: a biopsychosocial explanation for chronic widespread pain in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:465–73. 10.1007/s10067-006-0433-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011;152:S2–S15. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burri A, Ogata S, Vehof J, et al. . Chronic widespread pain: clinical comorbidities and psychological correlates. Pain 2015;156:1458–64. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burri A, Ogata S, Livshits G, et al. . The Association between chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain, depression and fatigue is genetically mediated. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140289 10.1371/journal.pone.0140289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Macdonald G, Leary MR. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychol Bull 2005;131:202–23. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet 2007;369:946–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60159-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Afari N, Ahumada SM, Wright LJ, et al. . Psychological trauma and functional somatic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2014;76:2 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000;85:317–32. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Galama JM, et al. . The persistence of fatigue in chronic fatigue syndrome and multiple sclerosis: development of a model. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:507–17. 10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00023-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCracken LM, Morley S. The psychological flexibility model: a basis for integration and progress in psychological approaches to chronic pain management. J Pain 2014;15:221–34. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Halliday N, Treanor C, Galvin R, et al. . Effectiveness of multidisciplinary pain Rehabilitation Programs for patients with Fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2015;67:1423–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. . Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. The Cochrane Library 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vos-Vromans DC, Smeets RJ, Huijnen IP, et al. . Multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment versus cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Intern Med 2016;279:268–82. 10.1111/joim.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, et al. . Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008;47:670–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garschagen A, Steegers MA, van Bergen AH, et al. . Is there a need for including Spiritual Care in Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation of chronic pain patients? investigating an Innovative strategy. Pain Pract 2015;15:671–87. 10.1111/papr.12234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. . Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 2016;45:5–31. 10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersson G. Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016;12:157–79. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wentzel J, van der Vaart R, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. . Mixing online and Face-to-Face therapy: how to benefit from Blended Care in Mental Health Care. JMIR Ment Health 2016;3:e9 10.2196/mental.4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol 2014;69:153–66. 10.1037/a0035747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peng W, Lin JH, Crouse J. Is playing exergames really exercising? A meta-analysis of energy expenditure in active video games. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2011;14:681–8. 10.1089/cyber.2010.0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lumsden J, Edwards EA, Lawrence NS, et al. . Gamification of Cognitive Assessment and Cognitive training: a Systematic review of applications and efficacy. JMIR Serious Games 2016;4:e11 10.2196/games.5888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Turner WA, Casey LM. Outcomes associated with virtual reality in psychological interventions: where are we now? Clin Psychol Rev 2014;34:634–44. 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malloy KM, Milling LS. The effectiveness of virtual reality distraction for pain reduction: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:1011–8. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Laver K, George S, Thomas S, et al. . Virtual reality for stroke rehabilitation: an abridged version of a Cochrane review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2015;51:497–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Horne-Moyer HL, Moyer BH, Messer DC, et al. . The use of electronic Games in therapy: a review with clinical implications. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16:1–9. 10.1007/s11920-014-0520-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kharrazi H, Lu AS, Gharghabi F, et al. . A scoping review of Health Game Research: past, present, and future. Games Health J 2012;1:153–64. 10.1089/g4h.2012.0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DasMahapatra P, Chiauzzi E, Pujol LM, et al. . Mediators and moderators of chronic pain outcomes in an online self-management program. Clin J Pain 2015;31:404–13. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Fox JP, et al. . Psychological flexibility and catastrophizing as associated change mechanisms during online acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain. Behav Res Ther 2015;74:50–9. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baranowski T, Buday R, Thompson DI, et al. . Playing for real: video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:e10:74–82. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ryan RM, Rigby CS, Przybylski A. The Motivational Pull of Video Games: a Self-Determination Theory Approach. Motiv Emot 2006;30:344–60. 10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Connolly TM, Boyle EA, MacArthur E, et al. . A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput Educ 2012;59:661–86. 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim B, Park H, Baek Y. Not just fun, but serious strategies: using meta-cognitive strategies in game-based learning. Comput Educ 2009;52:800–10. 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. . Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci 2013;8:22 10.1186/1748-5908-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, et al. . Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 2010;12:e4 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elbert NJ, van Os-Medendorp H, van Renselaar W, et al. . Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ehealth interventions in somatic diseases: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e110 10.2196/jmir.2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berwick DM. The science of improvement. JAMA 2008;299:1182–4. 10.1001/jama.299.10.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Weise C, Kleinstäuber M, Andersson G. Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Tinnitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosom Med 2016;78:501–10. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wouters P, van Oostendorp H. A meta-analytic review of the role of instructional support in game-based learning. Comput Educ 2013;60:412–25. 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.07.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wouters P, van Nimwegen C, van Oostendorp H, et al. . A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. J Educ Psychol 2013;105:249–65. 10.1037/a0031311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crookall D. Serious Games, debriefing, and Simulation/Gaming as a discipline. Simul Gaming 2010;41:898–920. 10.1177/1046878110390784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2007.

- 55. Arrindell WA, Ettema J. SCL-90: handleiding bij een multidimensionele psychopathologie-indicator: Swets test publishers, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Swinkels-Meewisse EJ, Swinkels RA, Verbeek AL, et al. . Psychometric properties of the Tampa Scale for kinesiophobia and the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in acute low back pain. Man Ther 2003;8:29–36. 10.1054/math.2002.0484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vago DR, Silbersweig DA. Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): a framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness. Front Hum Neurosci 2012;6:296 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Morley S. The self in pain. Rev Pain 2010;4:24–7. 10.1177/204946371000400106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Graafland M, Dankbaar M, Mert A, et al. . How to systematically assess serious games applied to health care. JMIR Serious Games 2014;2:e11 10.2196/games.3825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, et al. . Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci 2008;12:163–9. 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation: Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zijlema WL, Stolk RP, Löwe B, et al. . BioSHaRE. How to assess common somatic symptoms in large-scale studies: a systematic review of questionnaires. J Psychosom Res 2013;74:459–68. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.03.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dittner AJ, Wessely SC, Brown RG. The assessment of fatigue: a practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:157–70. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00371-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. . Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust 2004;180:S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lessiter J, Freeman J, Keogh E, et al. . A Cross-Media Presence Questionnaire: the ITC-Sense of presence inventory. Presence 2001;10:282–97. 10.1162/105474601300343612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Venkatesh V, Thong JY, Xu X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS quarterly 2012;36:157–78. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–70. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fu F-L, Su R-C, Yu S-C. EGameFlow: A scale to measure learners’ enjoyment of e-learning games. Comput Educ 2009;52:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004;6:e34 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, et al. . A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain 1994;56:217–26. 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Spinhoven P, Ter Kuile M, Kole-Snijders AM, et al. . Catastrophizing and internal pain control as mediators of outcome in the multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain 2004;8:211–9. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care 1992:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thompson ER. Development and Validation of an internationally reliable Short-Form of the positive and negative Affect schedule (PANAS). J Cross Cult Psychol 2007;38:227–42. 10.1177/0022022106297301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Manzano A. The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation 2016;22:342–60. 10.1177/1356389016638615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Spijkerman MP, Pots WT, Bohlmeijer ET. Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;45:102–14. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:587–92. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chiauzzi E, Pujol LA, Wood M, et al. . painACTION-back pain: a self-management website for people with chronic back pain. Pain Med 2010;11:1044–58. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Veehof MM, et al. . Internet-based guided self-help intervention for chronic pain based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Behav Med 2015;38:66–80. 10.1007/s10865-014-9579-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schreurs PJG, Van de Willige G, Brosschot JF, et al. ; De Utrechtse coping lijst: omgaan met problemen en gebeurtenissen: Pearson, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016394supp001.pdf (400.8KB, pdf)