Abstract

Objectives

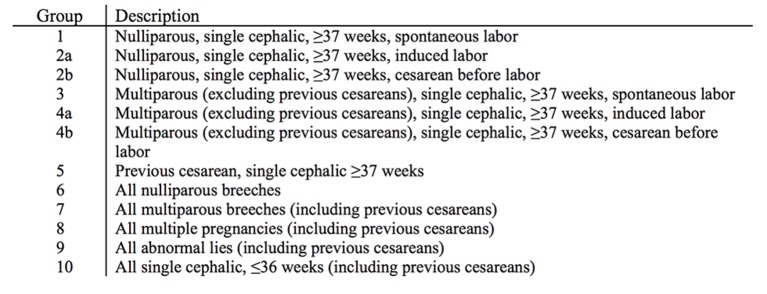

Internationally, the 10-Group Classification System (TGCS) has been used to report caesarean section rates, but analysis of other outcomes is also recommended. We now aim to present the TGCS as a method to assess outcomes of labour and delivery using routine collection of perinatal information.

Design

This research is a methodological study to describe the use of the TGCS.

Setting

Stavanger University Hospital (SUH), Norway, National Maternity Hospital Dublin, Ireland and Slovenian National Perinatal Database (SLO), Slovenia.

Participants

9848 women from SUH, Norway, 9250 women from National Maternity Hospital Dublin, Ireland and 106 167 women, from SLO, Slovenia.

Main outcome measures

All women were classified according to the TGCS within which caesarean section, oxytocin augmentation, epidural analgesia, operative vaginal deliveries, episiotomy, sphincter rupture, postpartum haemorrhage, blood transfusion, maternal age >35 years, body mass index >30, Apgar score, umbilical cord pH, hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy, antepartum and perinatal deaths were incorporated.

Results

There were significant differences in the sizes of the groups of women and the incidences of events and outcomes within the TGCS between the three perinatal databases.

Conclusions

The TGCS is a standardised objective classification system where events and outcomes of labour and delivery can be incorporated. Obstetric core events and outcomes should be agreed and defined to set standards of care. This method provides continuous and available observations from delivery wards, possibly used for further interpretation, questions and international comparisons. The definition of quality may vary in different units and can only be ascertained when all the necessary information is available and considered together.

Keywords: Caesareansection, quality of care, labouroutcome, neonatal outcome, the 10-Group Classification System, core outcome

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study proposes the use of an available method which may elaborate potential trends in delivery units and thus guide labour and delivery management.

Events and outcomes of labour are incorporated in the 10-Group Classification System (TGCS) from three different populations in Europe.

The TGCS is limited by unclear definitions of some of the outcomes used and encourage the importance of an agreed set of obstetric core outcomes.

Comparing obstetric outcomes using the TGCS do not adjust for risk factors.

The design as a quantitative descriptive study limits the ability to explore causes of the different frequencies of outcomes and events observed.

Introduction

Safety, consistency and quality in labour and delivery are key priorities for all labour and delivery units. It is difficult to determine what quality in labour and delivery is, but attempts to develop important outcomes are taking place.1–4 An agreed classification system, incorporating key outcomes that are objective, measurable and relevant to clinical practice, is required to assess consistency and quality of care.

Clinical practice and guidelines do vary internationally and occasionally also nationally. However, agreeing on a standard classification for assessment of quality of care should be less contentious. It is essential that providers and users of maternity care are aware of events and outcomes in their units and in addition having the ability to compare their results objectively over time and to other units. Only then can assessment of the quality of care take place.5 6 The emphasis on evidence-based medicine should be supported by prospective databases combined with a multidisciplinary quality audit programme. Acceptance and commitment to this philosophy will provide insight about labour and delivery and importantly ensuring that we are providing safe and quality care.7

The 10-Group Classification System (TGCS) was first described in 2001 and originally popularised as a method to assess caesarean section rates.8 The intention, however, was to introduce a generic perinatal classification to assess all perinatal events and outcomes of which caesarean section is only one. The way the 10 groups are structured make them relevant to all clinicians and women themselves and can provide a common language and starting point for any discussion on safety, quality of care and perinatal audit.9 The TGCS is endorsed by the WHO and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and increasingly used by labour and delivery units to report their caesarean section rates.10–18 The WHO and FIGO also recommend that other events and outcomes surrounding labour and delivery are analysed in relation to caesarean section using this classification.

This paper classifies data from three perinatal databases in different countries and explores the usefulness of the TGCS as a method to assess the quality of care. It also discusses the challenges that occur even using a standard classification system.

Methods

Data related to pregnancies and deliveries were prospectively collected in Stavanger University Hospital (SUH), Norway (2010–2011), National Maternity Hospital Dublin (NMH), Ireland (2011) and Slovenian National Perinatal Database (SLO), Slovenia (2007–2011). The study population included 9848 women in SUH, 9250 women in NMH and 106 167 women in SLO. All women were classified according to the TGCS (figure 1). The NMH had a complete TGCS registration initially. A complete registration was also confirmed at SUH and SLO after crosschecking of data. Caesarean section was defined as after spontaneous onset, induction or pre-labour. Prepregnancy body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. Episiotomies were either lateral or mediolateral and perineal tears affecting the external or the external and internal sphincter were classified as obstetric anal sphincter injuries. The attending midwife or obstetrician visually estimated blood loss and postpartum haemorrhage >1000 mL were registered at SUH and NMH, and postpartum haemorrhage >500 mL in SLO.

Figure 1.

The 10-Group Classification System.

Perinatal deaths included all intrauterine deaths after 22 weeks gestational age and within the first week after delivery. Hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy was classified using the Sarnat or modified Sarnat definition as grade I (mild), grade II (moderate) and grade III (severe). All data are presented as descriptive statistic and any comparisons between groups and hospitals described in the manuscript do not represent statistically significant differences.

Stavanger University Hospital

SUH has a catchment population of approximately 320 000 and is the regional maternity unit in the west of Norway. It has a tradition of low obstetrical intervention rates. Women with one previous caesarean were encouraged to deliver vaginally. Information related to pregnancies and deliveries was prospectively collected and recorded in an electronic obstetrical journal system (Natus).

The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics classified the study as a quality assurance study of routinely recorded data (REK Vest 2012/1522) and the local committee for data protection (2012/41) approved the project.

National Maternity Hospital

The NMH is a tertiary referral maternity hospital in Dublin, Ireland and one of the largest labour and delivery units in Europe delivering over 9000 women a year. It is well known for its Active Management of Labor philosophy on labour.19 This package of care is based on the prevention of prolonged labour and the physical and emotional sequelae that follow. Labour and delivery information is collected prospectively on an obstetrical and neonatal database. The hospital has traditionally for many years completed an Annual Clinical Report detailing each year’s results.

Slovenian national database

Slovenia is a European Union member state in Central Europe with approximately 2.1 million inhabitants and 20 000 deliveries per year. Healthcare in Slovenia is a public service provided through the public health service network. Perinatal care is almost entirely covered by compulsory health insurance, which is publicly funded. Slovenia has had a National Perinatal Information System since 1987 and registration into a computerised database by the attending midwife and doctor is mandatory. Data from all 14 countries’ maternity unit are collected. To assure quality of data collection, controls are built in the computerised system and audited periodically.

Results

The populations contained 43%, 46% and 48% nulliparous women in SUH, NMH and SLO. The overall caesarean section rates were 13.6%, 21.4% and 17.4% in SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively. The highest rate of caesarean in groups 1 and 2a was observed in SLO. NMH presents the lowest rate of caesarean in group 3 and SUH the lowest rate in group 5. Rupture of the uterus was diagnosed in 0.02% (2/9848) women in SUH, no women in NMH and 0.04% (39/106 167) women in SLO during the study period. The relative sizes of the groups and caesarean section rates are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

The TGCS for SUH, NMH and SLO 2007–2011

| Relative size of the group (%) | CD rate in each group (%) | Contribution made to overall CD rate (%) | |||||||

| Overall | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH (340/9848) |

NMH (1980/9250) |

SLO (18 454/106 167) |

SUH CD rate 13.6 |

NMH CD rate 21.4 |

SLO CD rate 17.4 |

| Group 1 | 28.9 | 25.8 | 33.2 | 6.5 | 7.4 | 10.0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Group 2 Group 2a Group 2b |

9.3 8.6 0.5 |

14.8 13.8 1.0 |

10.1 9.1 1.0 |

25.7 19.6 100.0 |

34.9 30.2 100.0 |

30.4 23.0 100.0 |

2.4 1.7 0.5 |

5.3 4.2 1.0 |

3.1 2.1 1.0 |

| Group 3 | 37.9 | 29.8 | 32.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Group 4 Group 4a Group 4b |

9.7 8.4 1.3 |

9.4 8.7 0.7 |

8.8 7.9 1.0 |

19.5 6.4 100.0 |

12.7 5.8 100.0 |

14.9 4.2 100.0 |

1.9 0.5 1.3 |

1.2 0.5 0.7 |

1.3 0.3 1.0 |

| Group 5 | 5.5 | 10.2 | 4.8 | 46.0 | 60.9 | 74.7 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 3.6 |

| Group 6 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 79.4 | 93.2 | 82.6 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

| Group 7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 66.7 | 85.0 | 71.7 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Group 8 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 40.8 | 64.9 | 54.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Group 9 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 100.0 | 100 | 92.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Group 10 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 31.9 | 37.6 | 22.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 |

CD, cesarean delivery; NMH, National Maternity Hospital 2011; SLO, Slovenian National Perinatal Database 2007–2011; SUH, Stavanger University Hospital 2010–2011; TGCS, 10-Group Classification System.

The overall prepregnant body mass index >30 was 9.7%, 12.8% and 8.3% and the frequency of maternal age >35 years was 14.9%, 32.2% and 14.9% in SUH, NMH and SLO respectively. The maternal characteristics stratified according to the TGCS are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics stratified in the TGCS groups 1–5

| Body mass index >30 (%) | Maternal age >35 years (%) | |||||

| SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | |

| Group 1 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 16.7 | 6.3 |

| Group 2a | 10.3 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 25.4 | 8.1 |

| Group 2b | 9.8 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 21.7 | 46.7 | 23.4 |

| Group 3 | 6.1 | 11.4 | 8.2 | 18.5 | 37.3 | 20.5 |

| Group 4a | 12.6 | 16.1 | 14.9 | 23.0 | 45.9 | 23.7 |

| Group 4b | 16.7 | 14.3 | 16.6 | 32.8 | 57.1 | 27.8 |

| Group 5 | 11.6 | 19.1 | 14.8 | 26.7 | 46.2 | 23.8 |

NMH, National Maternity Hospital 2011; SLO, Slovenian National Perinatal Database 2007–2011; SUH, Stavanger University Hospital 2010–2011; TGCS, 1-Group Classification System.

The overall use of epidural analgesia varied from 35.0% at SUH and 49.0% at NMH to 2.7% in SLO. The overall operative vaginal delivery rate varied from 12.7%, 11.9% and 3.2% in SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively. The overall induction rates were 20.1%, 24.9% and 23.5% and the frequencies of use of oxytocin were 23.6%, 28.3% and 57.3% in SUH, NMH and SLO. The overall rates of episiotomy were 19.7%, 28.7% and 32.0% and the rates of obstetric anal sphincter injuries were 1.5%, 1.5% and 0.3% in SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively. The overall red cell blood transfusion rate was 2.7%, 1.4% and 0.2% in SUH, NMH and SLO. Labour outcomes stratified according to the TGCS groups 1–5 are presented in tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Labour outcomes stratified in the TGCS groups 1–5

| Episiotomy (%) | Obstetric anal sphincter injuries (%) | Duration of labour >12 hours (%) | Operative vaginal delivery (%) | |||||||||

| SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | |

| Group 1 | 35.8 | 56.8 | 50.9 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 11.3 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 23.7 | 24.6 | 5.9 |

| Group 2a | 40.6 | 46.1 | 45.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 31.9 | 23.4 | 7.2 |

| Group 2b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Group 3 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 20.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| Group 4a | 11.8 | 12.2 | 21.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| Group 4b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Group 5 | 17.9 | 18.7 | 12.1 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 10.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 13.8 | 8.3 | 1.7 |

NA, not applicable; SUH, Stavanger University Hospital 2010–2011; NMH, National Maternity Hospital 2011; SLO, Slovenian National Perinatal Database 2007–2011; TGCS, 10-Group Classification System.

Table 4.

Labour outcomes stratified in the TGCS groups 1–5

| Acceleration with oxytocin (%) | Epidural in labour (%) | Postpartum haemorrhage >1000 mL (%) | Transfusions (%) | |||||||||

| SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | |

| Group 1 | 33.2 | 53.2 | 69.1 | 43.7 | 73.7 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 1.0 | x | 2.6 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Group 2a | 68.3 | 69.0 | 79.4 | 71.8 | 76.1 | 5.3 | 9.9 | 3.1 | x | 2.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 |

| Group 2b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17.6 | 1.1 | x | 2.0 | x | 0.4 |

| Group 3 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 43.5 | 19.2 | 34.9 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 0.5 | x | 2.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Group 4a | 46.9 | 25.0 | 68.5 | 44.7 | 48.2 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 1.1 | x | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Group 4b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5.6 | 4.8 | x | 1.6 | x | 0.6 |

| Group 5 | 12.7 | 9.0 | 23.0 | 39.8 | 31.7 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 1.6 | x | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.2 |

x, missing data; NA, not applicable; NMH, National Maternity Hospital 2011; SLO, Slovenian National Perinatal Database 2007–2011; SUH, Stavanger University Hospital 2010–2011; TGCS, 10-Group Classification System.

Overall perinatal death in SUH was 4.2 per 1000, in NMH 3.9 per 1000 and 5.0 per 1000 (540/108 070) in SLO. Perinatal deaths among groups 1 and 2 together were 1.3‰, 1.4‰ and 1.2‰, among groups 3 and 4 together 0.1‰, 0.8‰ and 1.2‰ and among women with previous caesarean (group 5) 5.5‰, 0‰ and 0.9‰ in SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively. Neonatal outcomes stratified according to the TGCS 1–5 are presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Neonatal outcomes stratified in the TGCS groups 1–5

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min (%) | Umbilical cord pH <7.0 (%) | Antepartum death (‰) | Hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy (‰) | Perinatal death (‰) | |||||||||||

| SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | SUH | NMH | SLO | |

| Group 1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | x | 0.7 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Group 2a | 2.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.3 | x | 2.4 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 3.2 |

| Group 2b | 0 | x | 0.7 | 0 | x | x | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 |

| Group 3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0 | x | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Group 4a | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.9 | x | 2.4 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.9 |

| Group 4b | 0 | x | 0.8 | 0 | x | x | 7.5 | 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 7.5 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Group 5 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.4 | x | 5.5 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 0 | 1.0 |

x, missing data; NMH, National Maternity Hospital 2011; SLO, Slovenian National Perinatal Database 2007–2011; SUH, Stavanger University Hospital 2010–2011.

Discussion

Every labour and delivery unit has a responsibility to record and publish their results. The results also need to be presented in a standardised and structured way, as the management and implications will vary in different groups of women. Any one event or outcome cannot be considered on their own without the understanding of any effects on other events, outcomes or complications. Care during labour and delivery has changed dramatically over the last 30 years.20 In particular, the caesarean section rate has risen and a common classification system might be helpful exploring benefits and risks associated to this intervention.

Limitations

Several challenges were discovered writing this manuscript. When comparing maternal, labour and perinatal outcomes between units and countries, objective variables (blood transfusion rates, perinatal deaths) have advantages over subjective assessed outcomes (postpartum haemorrhage, Apgar score <7 and hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy). In addition, some of our outcomes were differently defined and registered such as postpartum haemorrhage. This issue has been recognised and highlighted as a general problem in clinical trials.3 4 21 Standardising and agreeing on which core outcomes to be used to assess quality would not only increase the usefulness of the information collected but also encourage delivery units to use the same definitions. Due to different databases and registration, we only succeeded in completing table 1 with data from all the 10 groups. Ensuring quality data from national databases may be challenging and the low rates in SLO particularly of obstetric anal sphincter injuries, and transfusion rates should have been validated. Even more important is the need for a structured and standardised collection and registration of defined core outcomes in delivery units and in national registers.

We present the use of the TGCS as a method of which possible patterns within the observed population may uncover. This does not include risk adjustment, which limits the ability to compare absolute percentages of the outcomes observed. However, by comparing outcomes and events between standardised groups of women, hypotheses requiring further attention might be suggested. To explore causality, further studies are needed.

The TGCS

To achieve good data quality, proper registration and standardised definitions of outcomes are essential. The ability to classify all deliveries into one of the 10 groups is however a quality indicator which many institutions, countries and perinatal databases struggle to do.5 Stressing this issue is important as the reliability of the data may affect the interpretation if the number of unclassified cases is significant. By presenting data using the TGCS, the ability to demonstrate significant differences in smaller units is limited. However, examining even a small number of cases may be helpful to develop local strategies to improve the quality of care.14 Risk is not only the chance of certain events occurring but also the implications if it did occur.

The TGCS presents a method of risk stratification, which visualises how the caesarean section rate varies between different units and countries. Interpretation of other outcomes in the different groups may be used as a guidance to assess obstetric quality. Caesarean section rates can only be evaluated if perinatal and maternal outcomes are included.14 22 Using the TGCS, there are only three possible explanations for differences in the sizes of the groups and the events and outcomes within the groups: data quality, significant differences in important epidemiological variables and differences in clinical practice.9

To improve management in labour and optimising care, collection and simple interpretation of data are necessary.1 The data quality must be validated and by working together at multiple levels within the unit, improvements and adverse trends can be detected.2 The TGCS is shown to be consistent in size and the different caesarean section rates in the groups together with the size allow an informative interpretation of a given overall caesarean section rate (table 1). When other epidemiological information, events, outcomes and processes are analysed within the different groups as opposed to a proportion of the overall population, they increase in relevance. The TGCS do not adjust for risk factors, but by quantifying patient’s populations and different practice patterns, it allows a comparison of clinical value and may encourage a more in-depth analysis of individual groups or subgroups. Following are some examples of how our observations may be interpreted.

Focusing on the management of both physical and emotional care of nulliparous women (group 1) is important as this will prevent the caesarean rate from a further increase when these women return for a future delivery.23 24 SLO has an overall lower caesarean section rate than NMH, but a higher caesarean section rate of 10% in group 1 (table 1). Table 5 shows that lower caesarean section rates at SUH and NMH do not compromise good perinatal outcome.

A greater than a 2:1 ratio of the size of groups 1 and 2 reflects a low intervention rate in term single cephalic nulliparous women.5 This is influenced by culture, obstetric practice and case mix of the particular population. The ratios in our populations were 3.1, 1.7 and 3.3 for SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively. The definition of prelabour caesarean will additionally define in which group the women are classified (group 1 or group 2b) with an impact of this ratio. Clearly, the benefits of labour induction must be weighed against the potential maternal and fetal risks associated with the procedure, as well as knowledge of the population and the incidence of antenatal stillbirths.23 25 Maternity care before and in relation to the management of labour will further influence to which group and following risk the woman belongs to in her next pregnancy (group 3, 4 or 5).10 The rate of caesarean section in the subsequent pregnancy was 5.3%, 3.8% and 5.1% (SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively) in women without a previous caesarean (groups 3 and 4 combined) compared with 46.0%, 60.5% and 74.7% (SUH, NMH and SLO, respectively) in women with a previous caesarean (group 5).

As presented in table 2, the women delivering at NMH were in all groups older than the women delivering at SUH and in SLO. When comparing caesarean section rates (table 1), the low rate at NMH in group 1 might reflect a certain type of labour management as high maternal age is normally associated with an increased incidence of interventions.

SUH has the lowest overall caesarean section rate and the lowest overall use of oxytocin. However, stratified by the TGCS, the use of oxytocin at SUH was lowest in group 1 only. SUH practice a judicious use of oxytocin that includes a definition of the start of active labour, prolonged labour and thereby indication for oxytocin use, which differ from NMH and SLO.26 Compared with NMH and their philosophy of prevention of prolonged labour this may lead to more labours that are prolonged. The package of Active Management of Labor with one to one care and its advantages practised at NMH and in SLO has always been an issue of much debate.27 The role of oxytocin in labour management is important, but the optimal dose and timing is yet to be revealed.26 The different types of labour management probably explain the different rates of oxytocin augmentation and prolonged labours observed (tables 3 and 4).

Furthermore, by using the TGCS, a higher rate of obstetric anal sphincter injuries among women in groups 2a and 5 at SUH is evident which deserves closer investigation. The overall rate of severe postpartum haemorrhage at SUH is relatively at least high and in addition proportionally higher than the transfusion rates.28 This highlights the importance of analysing both subjective (estimated blood loss) outcomes together with objective (transfusion rates) when evaluating obstetric practice.21 29

Compared with SUH and NMH, the operative vaginal delivery rate is lower in SLO. The risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes increases with an operative vaginal delivery but if the alternative is a caesarean at full dilatation, the risk benefit ratio must be carefully considered.30 Occurrence of maternal and neonatal complications is, however, similar to SUH and NMH with the exception of lower sphincter rupture rates in all groups.

Conclusion

Caesarean section rates, maternal characteristics together with labour and fetal outcomes need to be defined by using the same classification system. We propose the TGCS as the standardised method of assessing events and outcomes and comparing interinstitutional rates, which may contribute to the judgement of quality of care in labour and delivery. By working together and sharing our knowledge, we can learn from each other. The first step in providing quality of care is to be aware of your results.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JR, ML, TME and MR contributed to the idea and design of the study. JR, ML, NT, MM and TME contributed to the preparation of the data used. JR, TME, IV and MR assisted in the literature research and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have no financial and material support to report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Sibanda T, Fox R, Draycott TJ, et al. Intrapartum care quality indicators: a systematic approach for achieving consensus. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;166:23–9. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sprague AE, Dunn SI, Fell DB, et al. Measuring quality in maternal-newborn care: developing a clinical dashboard. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:29–38. 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)31045-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan K. Chief Editors of Journals participating in The CI. the CROWN Initiative: journal editors invite researchers to develop core outcomes in women's health. BJOG 2016;123(Suppl 3):103–4. 10.1186/s40834-016-0024-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Geirsson RT, Eggebø T. Core outcomes for reporting women's health. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93:843–4. 10.1111/aogs.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robson M, Hartigan L, Murphy M. Methods of achieving and maintaining an appropriate caesarean section rate. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013;27:297–308. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gee RE, Winkler R. Quality measurement: what it means for obstetricians and gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:507–10. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182840e20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawrence HC, Copel JA, O'Keeffe DF, et al. Quality patient care in labor and delivery: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:147–8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robson MS. Classification of caesarean sections. Fetal Matern Med Rev 2001;12:23–39. 10.1017/S0965539501000122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robson M. The Ten Group Classification System (TGCS)—a common starting point for more detailed analysis. BJOG 2015;122:701 10.1111/1471-0528.13267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brennan DJ, Robson MS, Murphy M, et al. Comparative analysis of international cesarean delivery rates using 10-group classification identifies significant variation in spontaneous labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:308.e1–308.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fischer A, LaCoursiere DY, Barnard P, et al. Differences between hospitals in cesarean rates for term primigravidas with cephalic presentation. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:816–21. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000156299.52668.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scarella A, Chamy V, Sepúlveda M, et al. Medical audit using the ten Group classification system and its impact on the cesarean section rate. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;154:136–40. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ciriello E, Locatelli A, Incerti M, et al. Comparative analysis of cesarean delivery rates over a 10-year period in a Single Institution using 10-class classification. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:2717–20. 10.3109/14767058.2012.712567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Homer CS, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, et al. A novel use of a classification system to audit severe maternal morbidity. Midwifery 2010;26:532–6. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Betran AP, Torloni MR, Zhang JJ, et al. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG 2016;123:667–70. 10.1111/1471-0528.13526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Figo Working Group On Challenges In Care Of Mothers And Infants During Labour And Delivery. Best practice advice on the 10-Group Classification System for cesarean deliveries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;135:232–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chong C, Su LL, Biswas A. Changing trends of cesarean section births by the Robson Ten Group Classification in a tertiary teaching hospital. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:1422–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minsart AF, De Spiegelaere M, Englert Y, et al. Classification of cesarean sections among immigrants in Belgium. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:204–9. 10.1111/aogs.12003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O'Driscoll K, Foley M, MacDonald D. Active management of labor as an alternative to cesarean section for dystocia. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laughon SK, Branch DW, Beaver J, et al. Changes in labor patterns over 50 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:419.e1–419.e9. 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rath WH. Postpartum hemorrhage--update on problems of definitions and diagnosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:421–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nippita TA, Lee YY, Patterson JA, et al. Variation in hospital caesarean section rates and obstetric outcomes among nulliparae at term: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 2015;122:702–11. 10.1111/1471-0528.13281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brennan DJ, Murphy M, Robson MS, et al. The singleton, cephalic, nulliparous woman after 36 weeks of gestation: contribution to overall cesarean delivery rates. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117(2 Pt 1):273–9. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318204521a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barber EL, Lundsberg LS, Belanger K, et al. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:29–38. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins -- Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(2 Pt 1):386–97. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b48ef5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rossen J, Østborg TB, Lindtjørn E, et al. Judicious use of oxytocin augmentation for the management of prolonged labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:355–61. 10.1111/aogs.12821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown HC, Paranjothy S, Dowswell T, et al. Package of care for active management in labour for reducing caesarean section rates in low-risk women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;9:CD004907 10.1002/14651858.CD004907.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mousa HA, Alfirevic Z, Blum J. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;1:CD003249 10.1002/14651858.CD003249.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woiski MD, Scheepers HC, Liefers J, et al. Guideline-based development of quality indicators for prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94:1118–27. 10.1111/aogs.12718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walsh CA, Robson M, McAuliffe FM. Mode of delivery at term and adverse neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:122–8. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182749ac9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.