Abstract

Introduction

Despite positive health outcomes associated with advance care planning (ACP), little research has investigated the impact of ACP in surgical populations. Our goal is to evaluate how an ACP intervention video impacts the patient centredness and ACP of the patient-surgeon conversation during the presurgical consent visit. We hypothesise that patients who view the intervention will engage in a more patient-centred communication with their surgeons compared with patients who view a control video.

Methods and analysis

Randomised controlled superiority trial of an ACP video with two study arms (intervention ACP video and control video) and four visits (baseline, presurgical consent, postoperative 1 week and postoperative 1 month). Surgeons, patients, principal investigator and analysts are blinded to the randomisation assignment.

Setting

Single, academic, inner city and tertiary care hospital. Data collection began July 16, 2015 and continues to March 2017.

Participants

Patients recruited from nine surgical oncology clinics who are undergoing major cancer surgery.

Interventions

In the intervention arm, patients view a patient preparedness video developed through extensive engagement with patients, surgeons and other stakeholders. Patients randomised to the control arm viewed an informational video about the hospital surgical programme.

Main outcomes and measures

Primary Outcome: Patient centredness and ACP of patient-surgeon conversations during the presurgical consent visit as measured through the Roter Interaction Analysis System. Secondary outcomes: patient Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score; patient goals of care; patient, companion and surgeon satisfaction; video helpfulness; medical decision maker designation; and the frequency patients watch the video. Intent-to-treat analysis will be used to assess the impact of video assignment on outcomes. Sensitivity analyses will assess whether there are differential effects contingent on patient or surgeon characteristics.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine institutional review board and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02489799, First received: July 1, 2015).

Trial registration number

clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02489799.

Keywords: advance care planning, patient-centered outcomes research, video tools, Adult palliative care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The intervention being tested, as well as the trial outcomes, was developed and selected through extensive stakeholder – patient, family member, surgeon and palliative care clinician – engagement.

There is limited existing research of advance care planning and palliative care in surgical populations.

The study will enable a detailed examination of the patient experience surrounding major cancer surgery as well as an in-depth analysis of how surgeons and patients preoperatively discuss surgical risk.

The study intervention is a video and, thus, if effective, it can be easily disseminated.

The video was initially conceptualised for a pancreatic cancer population, though its content was broadened to address all major surgery; the final video addresses surgery, but not specifically pancreatic cancer or cancer surgery.

The selected outcomes and timeframe of the study (1 month following surgery) may be too short to fully capture the effect of the intervention.

Surgeon and surgery level factors could influence study outcomes. For example, perhaps certain types of surgery are more likely to be associated with perioperative patient depression scores.

The study cannot control for the potential effect of a patient's medical and surgical course on study outcomes.

Introduction

In 2010, there were approximately 51 million surgeries performed in the United States.1 Although most surgeries will be performed successfully, patient morbidity and mortality persist,2–5 and some surgeries require postoperative life-sustaining treatments in an intensive care unit.6 While patients may be stratified for perioperative complications, it is difficult to impossible to predict which patients will die or suffer a major perioperative complication.3 5 7

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process by which individuals contemplate future health states, clarify and discuss their goals and express goals-informed wishes for those health states – if illness may render that person unable to make decisions for him or herself in the future.8 Evidence supports that ACP discussions may decrease healthcare use, while increasing patient satisfaction, use of hospice and palliative care and compliance with a patient's end-of-life wishes.9–13 For family members, ACP may also decrease anxiety, depression and stress, while increasing satisfaction with the quality of care.9 14 15 ACP is appropriate throughout multiple stages of illness and has not been associated with harm in previous studies.16 Finally, the landmark 2014 Institute of Medicine report Dying in America advocates for increased ACP to explore patient wishes before they become acutely ill.17

As patients with advanced cancer undergoing major surgery often experience conditions that may increase their risk for both complications during surgery and postoperative outcomes (eg, functional decline, frailty, comorbidities and polypharmacy),18–22 it is likely beneficial for them to initiate ACP prior to surgery. A recent systematic review of palliative care interventions for surgical populations23 highlighted five studies that explored ACP interventions in surgical populations.24–28 These interventions involved further training or activation of surgical providers (ie, surgeons, anaesthesiologists and/or nurses) to have an ACP conversation with the patient prior to surgery and/or involvement of a palliative care specialist specifically to discuss ACP with the patient prior to surgery. These interventions found improved concordance and decreased decisional conflict between patients and surrogates about goals of care,24 25 27 improved documentation regarding power of attorney26 and were deemed helpful by study participants;25 none of these trials documented harms to patients or family members.

Verbal communication is the predominant modality for ACP between patients and providers29 and was the communication modality used in the above ACP interventions in surgical populations.24–28 Yet, there are multiple barriers to optimal verbal communication in the patient-doctor relationship. Most importantly, verbal communication about ACP is inherently inconsistent and subjective, as standardising these conversations is challenging to impossible.30–34 Conversations may also inaccurately convey the burden and outcomes of medical interventions, particularly when the patient has no previous knowledge or experience of aggressive medical treatments (ie, intubation, artificial ventilation, artificial nutrition) and/or settings (ie, an intensive care unit).35 While ACP innately requires verbal communication between patients and providers, such communication can be facilitated or enhanced through educational tools, such as a video. Video ACP tools have inherently stable content and thus may be a more objective, simple to understand and realistic modality through which to educate and activate patients about ACP.36 37 Thirteen randomised controlled trials in varying populations support that video-based ACP tools can empower patients and families to have ACP-related discussions,38–50 though none of these studies was completed in surgical populations.

This investigation builds on the paucity of research concerning video ACP tools in surgical populations.23 Towards this goal, a randomised controlled clinical trial was initiated (clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT02489799).

Objective

The objective of this study is to evaluate whether, compared with a control video, an ACP video developed for patients and families pursuing aggressive surgical treatment for cancer impacts the patient centredness and ACP of the patient-surgeon conversation during the audio-recorded presurgical consent visit. The trial is funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which supports comparative effectiveness research to help patients and other stakeholders make informed medical decisions.51 In light of this funding, the primary aim was selected based on 2 years of intense engagement with patients and family members, as well as other key stakeholders including surgeons, anaesthesiologists, surgical nurses, surgical intensive care unit (SICU) nurses, palliative care clinicians and health services researchers. We hypothesise that patients who view the intervention video will engage in a more patient-centred communication with their surgeons, as compared with patients who view the control video (Hypothesis 1).

Our secondary aims explore multiple other patient and companion outcomes. Of note, accompanying family members or friends (ie, ‘companions’) are often present during the audio-recording of the presurgical visit. Our secondary outcomes include the following: how the ACP intervention video may impact mood-related outcomes, such as patient anxiety and depression; helpfulness of the video (from patient and companion perspectives); the patient's stated goals of care; satisfaction with the presurgical consent visit (from patient, companion and surgeon perspectives, as well as from consensus perspectives); whether the patient designates a medical decision maker and discusses his/her wishes with this designated person; and the frequency with which patients watch the video outside of the site of recruitment. We will measure the patient's level of anxiety and depression during two separate presurgical visits, as well as 1 week after surgery and 1 month after surgery. We hypothesise that patients who view the intervention video will be less anxious and depressed across all visits, as compared with patients who view the control video (Hypothesis 2). We hypothesise that patients will find the intervention video more helpful than the control video (Hypothesis 3). We also hypothesise that that patients will watch the intervention video more often than the control video (Hypothesis 4).

Methods and analysis

Study design

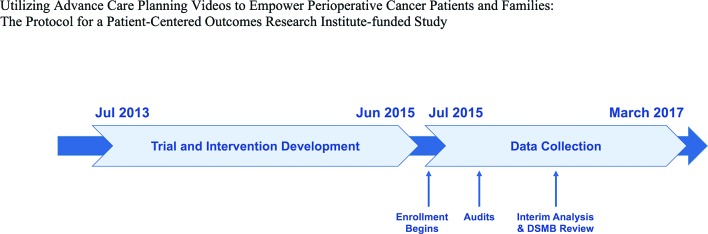

The study is a two-arm, randomised superiority trial of an ACP video developed for patients undergoing major surgery for advanced cancer at a single, academic, inner city, tertiary care hospital. The study began data collection on July 16, 2015 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial timeline.

Institutional review board determination

The Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center institutional review boards reviewed and approved the study protocol. All changes in study protocol, as needed, are to be submitted and reviewed by the institutional review board.

Study sample population

Our study sample includes patients undergoing major cancer surgery with one of nine surgeons participating in this study. These nine surgeons were chosen as they had sufficient cancer patient populations and were willing to be in the trial. All surgeons were comfortable with the ACP video and were shown both intervention and control videos prior to when data collection from their clinics commenced. In preparation for the study, surgeons described variations in their practice regarding presurgical visits and agreed on a single format to uniformly use for study patients; this format is composed of at least two visits with the surgeon prior to the actual surgery. Based on sample size calculations, explained in the Design justification section below, we aimed to recruit 90 patients for the study.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible patients must be undergoing major surgery such that, due to the surgery itself and/or the patient's underlying medical conditions, the surgeon plans to postoperatively admit the patient to SICU. Major surgery is defined as ‘surgery involving a risk to the life of the patient; specifically, an operation on an organ within the cranium, chest, abdomen or pelvic cavity.’52 Study patients must also be scheduled for non-emergent surgery such that they have at least a day to review the video prior to signing surgical consent. Potential study patients must also meet the following inclusion criteria: plan to undergo surgery with one of the study surgeons, able to give informed consent and able to speak English. Patients will be excluded if they are younger than 18 years old or have visual or hearing impairments such that they are unable to view and/or hear the study videos.

Many patients are accompanied to the surgeon's clinic by a family member or friend (ie, a ‘companion’). There is no screening of companions for eligibility to participate. If eligible patients have a companion present during the audio-recording, these individuals are orally consented prior to the recording. Companions under the age of 18 years cannot participate in the audio-recording unless consented by parent/guardian. The oncological surgeons (n=9) and any of their clinic staff or trainees also provide written consent to be audio-recorded.

Recruitment

Patients are recruited out of the nine surgical oncology clinics. Study staff wait in the clinics, and, if surgeons deem patients potentially eligible, study staff meet with patients to determine full eligibility, consent patients for the study and conduct the baseline visit activities.

Patients are provided with a $25 gift card on completion of the four visits of the study.

Due to the nature of major surgery, the study team anticipates some patient drop-out due to emotional distress, time constraints, surgery cancellation or patient death.

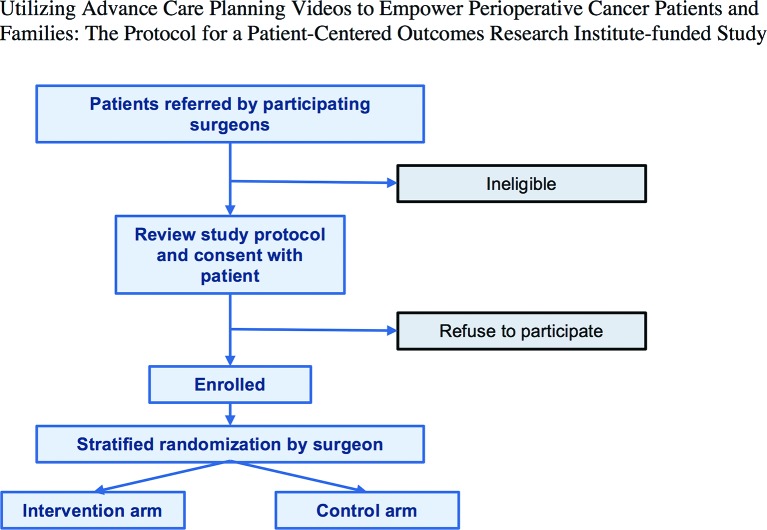

Randomisation

With each study patient as a unit of randomisation, we randomise immediately following enrolment so that the study patient receives either the intervention or the control video (figure 2). Patients are stratified by surgeon through a computer algorithm written in R,53 which performed a block randomisation with a block size of six. We are adopting a stratified approach to randomisation as we hypothesise that individual differences in surgeon demeanour may also impact study outcomes. We do not anticipate surgeons to recruit an equal number of patients given differences in practice type and volume; however, each surgeon was encouraged to recruit at least three patients to allow for clustering by surgeon in our analysis. The surgeons, patients, companions, principal investigator, coders and data analysts are blinded to the randomisation assignment; however, the recruitment staff cannot be blinded as they show the video and provide a video link to study patients.

Figure 2.

Trial enrolment diagram.

Study arms

Patients are randomly assigned to one of two arms: intervention video or control video. Patients are randomised on site by study staff on completion of patient consent. Both videos are 6 min in duration.

Intervention

Over the past 2 years, the study team developed a video-based ACP tool for patients pursuing aggressive surgical treatments. The video design process involved extensive engagement with patients and families and key stakeholders such as surgeons, palliative care clinicians, ACP experts and surgical nurses, and it included interviews, focus groups, stakeholder summits and a de-identified cross-sectional survey regarding potential video content (further manuscripts in process).54–57 The video features patients, companions and medical professionals (two surgeons, one anaesthesiologist, one SICU nurse) discussing both the course of a typical surgical day – preoperative area, operating room and SICU – and the importance of preoperative ACP – identifying a medical decision maker, discussing one's wishes with that decision maker and communicating those wishes to the surgical team prior to the surgery.

Control

The control video is an informational video about the Johns Hopkins surgery programme, which was created by the Marketing Department. The video catalogues the history and evolution of surgery at Johns Hopkins Medicine. The video highlights scientific developments and ongoing innovations in patient safety.

Primary outcome: Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS)

The primary outcome is the surgeon-patient conversation as analysed using the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS). RIAS is a quantitative coding system for medical dialogue, which has demonstrated reliability and predictive validity for patient satisfaction, use and adherence.58 The coding unit of analysis is a complete thought that varies in length from a single word to a sentence. The RIAS coder is blinded to the randomisation assignment of the patient and is unaware of the study hypotheses. RIAS coding has a reliability of >0.85 in most studies.58 This study will have one coder for all recordings.

RIAS will also be used to calculate a patient-centredness summary score, which has been used in past studies with predictive and concurrent validity for a variety of patient and physician outcomes.59 The patient-centredness summary score is a ratio of statements that reflect the psychosocial and socio-emotional elements of exchange about the lived illness experience of patients relative to statements that reflect a more biomedical and disease focused perspective. This score reflects the encounter as a whole, rather than an individual's dialogue. A value greater than 1 indicates a more patient-centred encounter; whereas, a value less than 1 indicates a more biomedical encounter. The coder also counts references to six, pre-determined ACP-related topics: medical decision maker, death (immediate perioperative), death (long term), positive surgery outcome, severity of planned surgery and goals of surgery.

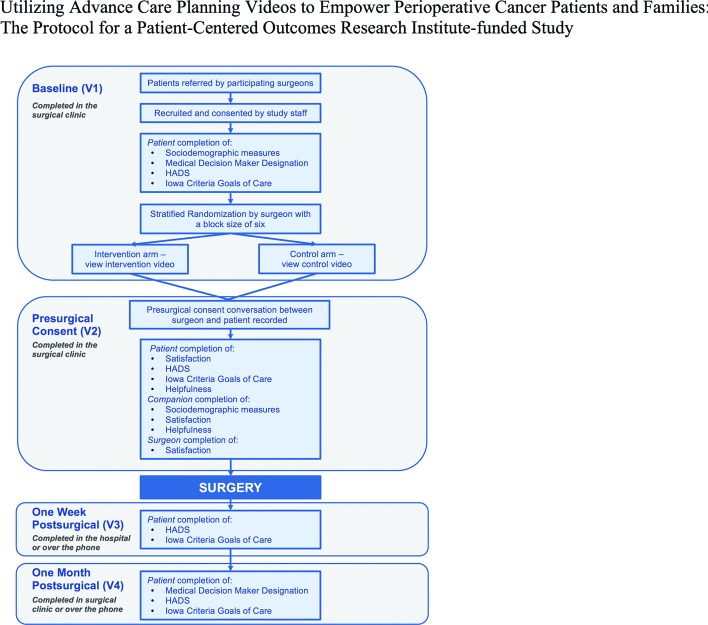

Patient trajectory and secondary outcomes

The study includes four visits with each study patient: baseline visit (V1, non-recorded), presurgical consent visit (V2, recorded), postoperative 1 week visit (V3, non-recorded) and postoperative 1 month visit (V4, non-recorded; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Data collection plan.

Baseline visit (V1)

Once consented for the study, patients complete self-administered measures including sociodemographic measures and a question concerning whether the patient has assigned a medical decision maker and how recently he/she has had a conversation with that medical decision maker about care preferences. Patients also complete the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)60 and the Iowa Criteria Goals of Care survey.61

Patients are randomised to either the intervention or control video. Patients then immediately view the video they were assigned in the presence of the study staff. Surgeon stakeholders involved in the design of the study recommended this timing for the video viewing. The study staff also provide the patient a web link to the video so that they may show the video to others in their family and/or to view the video again at a later time or place.

Presurgical consent visit (V2)

On patient arrival in the clinic waiting room prior to their visit with the surgeon, study staff greet the patient, offer to show the patient the video again and orally consent any companions who may be accompanying the patient. Once the patient is escorted back to an exam room, study staff place two recorders at different places in the room to capture the conversation during this visit. This audio-recording is used for the primary outcome RIAS analysis. For this study protocol, surgeons have agreed that the V2 goal is to discuss the risks and benefits of the upcoming surgery and for the patient to sign surgical consent. Immediately following this conversation, both the surgeon and the patient and/or companion complete the following questionnaires:

Satisfaction measures

After the visit, the surgeon, patient and companion each complete a short self-administered satisfaction questionnaire about the visit. The study team has adapted measures developed and used by Roter and colleagues in previous studies to address patient satisfaction with interpersonal and informational aspects of medical visits.62–65 The patient satisfaction questionnaire includes six items; an eight-item version used in a past study had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.89.66 The clinician satisfaction questionnaire includes six items; an eight-item version used in a past study had a Cronbach's alpha of 0.83.67 The companion satisfaction questionnaire includes eight items and has not been used in a past study, though it is directly based on the patient satisfaction questionnaire. The internal reliability of these questionnaires will be estimated with Cronbach's alpha.

Helpfulness survey

Patients also complete a measure regarding their perceptions of the helpfulness of the video. Volandes et al used this measure in their previous studies but do not report on the psychometric properties of the tool.36 38 44–46 48 This measure asks whether the patient was comfortable watching the video, whether the patient perceived the video to be helpful in preparing him/her for surgery and whether the patient would recommend the video to other patients.

Other V2 measures

Patients also complete HADS and the Iowa Criteria Goals of Care measure. Companions complete self-administered questions about the nature of their relationship with the patient, as well as a self-administered survey about the helpfulness of the video.

Postsurgical 1 week visit (V3)

Approximately 1 week after the patients' surgery, a study staff meets with patients while they are still in the hospital, but after they have been transferred from the intensive care unit to another unit. Patients complete the HADS and Iowa Criteria Goals of Care surveys.

Postsurgical 1 month visit (V4)

Approximately 1 month after the patients' surgery, study staff communicate with patients either in person during the patient's 1 month follow-up with the surgeon or over the phone. The patient completes the HADS and Iowa Criteria Goals of Care surveys. Patients also answer one question regarding whether the patient has assigned a medical decision maker and how recently he/she has had a conversation with that medical decision maker about care preferences.

Medical record abstraction

Outside the scheduled study visits, the study team abstract medical record information, which is incorporated as descriptive data on each patient. Information abstracted includes the patient's primary diagnosis, surgical procedure, active medical history (eg, hypertension, coronary artery disease), hospital admission and discharge (related to the major surgery they received) and any hospital readmission data collected within 1 month after the surgery. A second study team member independently verifies all medical record abstraction.

Data collection

Mode of data entry

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Johns Hopkins medical institutions.68 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing the following: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. Patients enter all surveys directly into REDCap68 on study computers; patients also have the option to complete surveys on paper at any point. Paper surveys are further available in the event of technical difficulties. Patients also have the option to complete questions verbally if they prefer not to input data into the computer or onto a paper form. Surgeon and companion surveys are completed on paper. All paper forms completed are entered into REDCap by one study staff member and independently verified by a second study staff member.

For medical record abstractions, the team uses information obtained from the hospital electronic medical record systems. Information is abstracted by one study staff member and independently verified by a second study staff member.

Statistical methods

Statistical significance and software

The team will set the overall level of statistical significance at p<0.05. All statistical analyses will be performed in Stata statistical software.69 Analysis will be rerun in R statistical software to confirm results.53

Intent-to-treat

Our study will use an intent-to-treat approach in which all data from study patients in both intervention and control arms are used, regardless of the level of adherence to the study arms. We have also designed the study to minimise the possibility of both patient crossovers between intervention groups, as well as to reduce the chance that patients may see the video to which they are not randomised.

Evaluation of hypotheses overview

Descriptive statistics will be calculated to summarise patients' characteristics and other baseline variables. Comparability of the intervention arm and the control arm will be assessed with regard to preintervention sociodemographic and health status measures derived from medical record abstraction. While randomisation should account for such differences, a two-sample t-test/Mann-Whitney test will be performed to investigate the difference in two means or medians for continuous variables, and Fisher's exact test or χ2 test will be used to investigate the difference in proportions for binary or categorical variables. We will therefrom identify and determine possible necessary adjustment for some baseline attributes. Historically, patient gender, age, race, education and health status have been identified as important attributes and are usually adjusted for in the model. Surgeon attributes will be examined similarly.

Further statistical analyses will explore the association between intervention assignment and each of the outcomes. Based on the type of the data, summary univariate (descriptive) statistics (mean, SD, median, IQR, max, min, count, percentage) of all outcomes stratified by intervention assignment will be provided. Descriptive time trend plots (multiple visits) stratified by intervention assignment will be presented for outcomes that are measured at multiple visits. These plots will allow for the visual comparison of change patterns before and after the intervention in the two arms. Differences in outcomes between two arms at each visit will be tested by two-sample t-test/Mann-Whitney test or Fisher's exact test/χ2 test, based on the data types of the outcomes.

For the primary outcome and some of the secondary outcomes, the descriptive statistical analyses will be followed by regression analyses, using mixed effects generalised linear models with link functions chosen that are specific to the data types of the outcomes. The data will have a two-level structure, being defined by individual patient nested within surgeons. To address the potential unmeasured influence of surgeon-level attributes on patient-level outcomes, we will model the variable ‘surgeon’ as a random intercept. In most cases, the parameter of interest is the coefficient of the arm indicator, to be estimated as the intervention effect. All standard errors will be computed using the robust method.

Hypothesis 1

Specifically, the primary outcome, patient centredness of patient-surgeon conversations during a presurgical consent visit as measured through RIAS, is a continuous variable. Therefore, mixed effects linear regression models will be used, adjusting for relevant covariates, with inclusion of a random intercept for surgeon to account for the correlation of outcome values from patients of the same surgeon.

Hypothesis 2

The secondary outcome HADS consists of two subscales, symptoms of anxiety and symptoms of depression. Subscale scores range from 0, indicating no distress, to 21, indicating maximum distress; a score higher than 7 indicates clinically meaningful anxiety or depression.60 We will therefore consider these two outcomes as two binary variables indicating the absence or presence of clinically meaningful anxiety or depression. HADS will be measured at all four visits. To examine the effect of the intervention on these two outcomes, mixed effects logistic regression models will be used, adjusting for baseline scores and other relevant covariates, with inclusion of a surgeon random intercept. This model will be used to assess the difference in HADS subscale scores between the two arms at V2 and V3 and then at V4. To assess the robustness of our estimates, an alternative model with the inclusion of interaction terms between arm indicator and visit indicator will be used to estimate the difference in differences from baseline to later visits between the two arms. This will provide us information on the changes in HADS scores across visits within each arm as well as how the change patterns differ between the two arms.

Hypothesis 3

The secondary outcome Video Helpfulness will be measured at V2, and it will be summarised into two categories, helpful versus not helpful. A mixed effects logistic regression, adjusting for relevant covariates, with a surgeon random intercept will be used to compare the helpfulness of the intervention video and the control video.

Hypothesis 4

The frequencies the intervention video and control video are watched by patients outside of the medical clinic (ie, the extent to which patients choose to watch the video on their own time outside of direct interaction with the study staff) will be presented for comparison.

Other outcomes and hypotheses

Goals of Care (Iowa Goals of Care) has two questions. The first asks patients to check their current medical goals relating to their surgery. The second asks patients to list and rank the top three goals. Goals of care data are to be collected at all four visits. We will stratify the data by intervention assignment, and we will then calculate frequencies and percentages of goals of care chosen and being ranked as top three goals at each visit to assess the changes in goals of care across visits and differences between the two arms.

Patient and Surgeon Satisfaction will be measured at the end of V2. The satisfaction score, as the sum of the scores of six questions (all in a Likert scale), ranges from 6 to 30, with a higher score indicating higher level of satisfaction. The intervention effects on patient satisfaction score and surgeon satisfaction score (surgeon's perception of patient's satisfaction level) will be examined separately by mixed effects linear regression models, adjusting for relevant covariates, with inclusion of a random intercept for surgeon. Future analyses will also explore whether discrepancy exists among patients', companions' and surgeons' perception.

Medical Decision Maker Designation will be measured at baseline and V4. It is an ordered categorical variable consisting of four possible answer options: (1) No, I don't have a medical decision maker; (2) Yes, I have a medical decision maker, but we have not specifically talked about this (what medical decisions they should make for me); (3) Yes, I have a medical decision maker, and our talk about this (what medical decisions they should make for me) was over 6 months ago; and (4) Yes, I have a medical decision maker, and our talk this (what medical decisions they should make for me) was within the last 6 months. We will construct a binary variable indicating whether there is an upward change in medical decision maker designation from V1 to V4. A mixed effects logistic regression, adjusting for baseline value and other relevant covariates, with a surgeon random intercept will be used to examine the difference in change patterns between the two arms.

Data monitoring

Data security

During the data collection period, only the study team has access to the REDCap site that links the IDs to study patients. The electronic dataset and recordings are stored on an encrypted computer that is password protected with a secure server. All paper copies of the consent form are stored in a locked filing cabinet.

Study management

We use standard processes to enhance data quality and reduce bias. We strive to have consistent recruitment staff at each study site, and all staff are required to follow the protocol document when interacting with patients. We monitor for data completeness on our REDCap data collection site to reduce missing or incomplete data, inaccuracies and measurement bias and excessive variability. If we find missing data, we will run exploratory analyses to determine the missing data pattern, and we will then run appropriate analyses to address the problem and account for it in our models.

Design justifications

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on a measure of patient centredness that was generated from RIAS. This measure incorporates the verbal contributions of patients, surgeons and companions. Steinwachs et al 67 used this patient centredness variable as the primary outcome in a study testing the effectiveness of a 20 min computer-based intervention to activate patients to address a quality of care with their providers.67 The intervention group experienced visits with significantly higher levels of patient centredness than the control group with an effect size of 0.6 (Cohen's d).67

With a 0.6 effect size, the required sample size is 72 patients (36 per group) for a one-tailed test of study hypotheses (power=0.8 and alpha=0.05). The study team determined that only a one-tailed test was necessary given that we are testing whether the intervention improves patient-centred communication. Based on the previous study,67 we hypothesise that we would obtain recordings for 80%–90% of recruited patients, with any discrepancies likely stemming from patient attrition, technology failure and/or scheduling miscommunication. Accounting for an 80% recordings rate, the study team will need to recruit 90 patients to obtain the desired number of 72 recordings.

Once recruitment is complete, a power analysis will be performed to determine whether a conclusive finding or pattern of findings is due to insufficient power or the intervention.

Superiority design

We powered our study for a one-tailed test as we believe that the intervention video will have a likely impact on the outcome.

Study organisation and institutional assurances

A Data and Safety Monitoring Board will independently review preliminary results after 50% of the data have been collected to determine whether the intervention is causing undue harm to the patients or their companions. In addition, per standard processes at our institution, the study will undergo a yearly audit. The hospital legal division was involved to ensure proper procedures for developing a video for research purpose and proper use of media releases.

Dissemination plan for results

This trial is registered and described on clinicaltrials.gov, and results will be posted on that website. Results will also be presented and discussed at relevant professional society academic meetings and through publication in scientific journals. The full dataset will be available from the study principal investigator, per reasonable request. In accordance with ethical publication practices, authorship related to any presentations or publications will be based on individuals having contributed substantial time and/or intellectual content (ie, study design, analysis, project conceptualisation, etc) related to the results being presented.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is a two-arm, randomised superiority trial comparing the effectiveness of an ACP video tool as compared with a control video at increasing the patient centredness and ACP of presurgical consent conversations between surgeons and patients preparing for major cancer surgery. The risk to participants is low.

The current study examines how ACP might be incorporated into surgical settings. As patients undergoing major surgery are at risk for perioperative morbidity and mortality, it is appropriate for these patients to initiate ACP prior to surgery. While the surgical consent process involves an explanation of the risks and benefits of the surgery, previous research70 suggests that surgeons may have difficulty discussing detailed ACP wishes. Using an ACP video, this study hopes to empower patients to have more meaningful presurgical contemplation and conversation with both family members and their surgical team concerning their goals and wishes prior to major surgery.

If effective, the ACP video could be easily disseminated among patients, family members, surgery clinics and/or other pertinent stakeholders. Timing of when the patient watches the video in relation to their surgery and/or their visit(s) with the surgeon can be determined in future studies or per individual decision by the patient or surgeon. In planning this study, participant surgeons noted practice variations within general ‘standard-of-care’ including that some surgeons routinely met with patients at least twice before the day of surgery, while others would meet only once. For the purpose of this study, participant surgeons agreed on the above-described standardised format of two presurgery visits and, therefore, timing of when the patient watched the video was standardised to be immediately after the surgeon recommended that the patient be scheduled for surgery.

In keeping with the principles of patient-centred outcomes research, both the intervention video and the resulting randomised control trial to assess its impact have been designed with extensive input from patients, family members, surgeons, health researchers and other stakeholders. This trial is also overseen by a readily available patient/family co-investigator who communicates at least monthly with the study team and reviews study progress as well as participates in data evaluation. Thus, the current investigation is patient centred in outcomes and in facilitation and data analysis.

Potential contributions of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation to explore the impact of a video ACP tool on surgeon, patient and family communication prior to major surgery. A strength of this study is that the intervention video and resulting randomised control trial were both developed based on input from patients, companions, surgeons, health services researchers and other stakeholders. Ultimately, the results of this randomised controlled trial may demonstrate that easy-to-disseminate videos may activate patients and improve the patient centredness of surgeon-patient interactions.

Limitations

Several limitations regarding the study should be noted. First, the intervention video was initially conceptualised for a pancreatic cancer surgical population, potentially creating an issue for the generalisability of the video to a wider surgical population. Although the video was initially developed for the pancreatic cancer setting, the severity of pancreatic cancer surgery is analogous to other high-mortality/high-morbidity cancer surgeries. Moreover, the video itself does not specifically discuss cancer or pancreatic cancer. Thus, the intervention video should be relevant to a range of surgical patients and their families and is being evaluated among a group of patients with diverse cancer diagnoses.

Second, the selected outcomes and timeframe of the study may not be able to fully capture the effect of the intervention as the impact of the surgery and video may persist beyond the 1 month timeframe of the study. In order to mitigate this concern, data for multiple patient-centred outcomes are collected, many of which have been previously validated and used in surgical settings. These outcomes enable multi-faceted evaluation of the intervention. Additionally, results will be examined at several timepoints, including both preoperatively (V1, V2) and postoperatively (V3, V4). Yet, as other studies have shown benefit of ACP discussions as far as 12 months after hospitalisation and patient death,71 we might also hypothesise further benefits of the intervention to be apparent just before and after patient death, which is outside of the current trial timeframe.

Third, surgeon-level factors will likely influence study outcomes. As all surgeons were privy to a general overview of the study and were provided with the opportunity to watch the intervention and control videos prior to agreeing to participate, the surgeons who ultimately decided to participate in the study may be biased in their pre-existing support for ACP. It is also possible that surgeons may have their own unconscious selection biases when referring patients to the study.

Fourth, one of the participating surgeons was featured in the intervention video. It is therefore possible that patients of this surgeon who are randomised to watch this video might surmise they are in the intervention group, which might impact their outcomes. In order to best account for these potential sources of bias, study randomisation is nested within surgeon site of recruitment. Further, the analysis plan's designation of the surgeon as a random intercept should address the potential unmeasured influence of surgeon-level attributes on patient-level outcomes.

A final limitation of the study is that it cannot control for the effect of a patient's medical course on study outcomes. Both presurgical factors such as diagnosis and postsurgical factors such as surgical course or change in prognosis might contribute to anxiety and depression, as well as to a patient's goals of care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RAA is the study principal investigator and she directed all study activities and coordinated between team members. Study design: RAA, SRI, TY, MW, AEV, JFPB and DLR; analysis design: RAA, SRI, TY, NLC and DLR; and protocol generation: RAA, SRI, NLC, AMCC and TY.

Funding: This work was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (CDR-12-11-4362).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Number of all-listed procedures for discharges from short-stay hospitals, by procedure category and age: United States, 2010. CDC - NCHS 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwarze ML, Shen Y, Hemmerich J, et al. Age-related trends in utilization and outcome of open and endovascular repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2006. J Vasc Surg 2009;50:722–9. 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kozower BD, Sheng S, O'Brien SM, et al. STS database risk models: predictors of mortality and major morbidity for lung cancer resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:875–83. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finlayson E, Fan Z, Birkmeyer JD. Outcomes in octogenarians undergoing high-risk cancer operation: a national study. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:729–34. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldman L, Caldera DL, Nussbaum SR, et al. Multifactorial index of cardiac risk in noncardiac surgical procedures. N Engl J Med 1977;297:845–50. 10.1056/NEJM197710202971601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lipsett PA, Swoboda SM, Dickerson J, et al. Survival and functional outcome after prolonged intensive care unit stay. Ann Surg 2000;231:262–8. 10.1097/00000658-200002000-00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ragulin-Coyne E, Carroll JE, Smith JK, et al. Perioperative mortality after pancreatectomy: a risk score to aid decision-making. Surgery 2012;152(3 Suppl 1):S120–7. 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khandelwal N, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, et al. Estimating the effect of palliative care interventions and advance care planning on ICU utilization: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1102–11. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Romer AL, Hammes BJ. Communication, trust, and making choices: advance care planning four years on. J Palliat Med 2004;7:335–40. 10.1089/109662104773709495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014;28:1000–25. 10.1177/0269216314526272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, et al. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:477–89. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Nelson CA, et al. Family decision-making to withdraw life-sustaining treatments from hospitalized patients. Nurs Res 2001;50:105–15. 10.1097/00006199-200103000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665–73. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bakitas M, Kryworuchko J, Matlock DD, et al. Palliative medicine and decision science: the critical need for a shared agenda to foster informed patient choice in serious illness. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1109–16. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeo HL, O'Mahoney PR, Lachs M, et al. Surgical oncology outcomes in the aging US population. J Surg Res 2016;205:11–18. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koppert LB, Lemmens VE, Coebergh JW, et al. Impact of age and co-morbidity on surgical resection rate and survival in patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2012;99:1693–700. 10.1002/bjs.8952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:901–8. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nohra E, Bochicchio GV. Management of the gastrointestinal tract and nutrition in the geriatric surgical patient. Surg Clin North Am 2015;95:85–101. 10.1016/j.suc.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, et al. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:661–74. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00363-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lilley EJ, Khan KT, Johnston FM, et al. Palliative care interventions for surgical patients: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2016;151:172–83. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Briggs LA, Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, et al. Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: a pilot study. J Prof Nurs 2004;20:47–58. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2003.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooper Z, Corso K, Bernacki R, et al. Conversations about treatment preferences before high-risk surgery: a pilot study in the preoperative testing center. J Palliat Med 2014;17:701–7. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grimaldo DA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Jurson T, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of advanced care planning discussions during preoperative evaluations. Anesthesiology 2001;95:43–50. 10.1097/00000542-200107000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Song MK, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care 2005;43:1049–53. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178192.10283.b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, et al. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86:493–500. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the "planning" in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:256–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA 2005;294:359–65. 10.1001/jama.294.3.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT principal investigators. JAMA 1995;274:1591–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT investigators. study to understand prognoses and preference for outcomes and risks of treatment. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Covinsky KE, Fuller JD, Yaffe K, et al. Communication and decision-making in seriously ill patients: findings of the SUPPORT project. the study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(5 Suppl):S187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roter DL, Larson S, Fischer GS, et al. Experts practice what they preach: a descriptive study of best and normative practices in end-of-life discussions. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barry MJ. Health decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in office practice. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:127–35. 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, et al. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Making 2010;30:701–11. 10.1177/0272989X10386231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. O'Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Deep KS, Hunter A, Murphy K, et al. "It helps me see with my heart": how video informs patients' rationale for decisions about future care in advanced dementia. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:229–34. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. El-Jawahri A, Mitchell SL, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cpr and intubation video decision support tool for hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1071–80. 10.1007/s11606-015-3200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 2016;134:52–60. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:305–10. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video in advance care planning for progressive pancreas and hepatobiliary cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2013;16:623–31. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, et al. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. J Palliat Med 2008;11:700–6. 10.1089/jpm.2007.0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Volandes AE, Barry MJ, Chang Y, et al. Improving decision making at the end of life with video images. Med Decis Making 2010;30:29–34. 10.1177/0272989X09341587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals-of-care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med 2012;15:805–11. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, et al. Assessing end-of-life preferences for advanced dementia in rural patients using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2011;14:169–77. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Volandes AE, Lehmann LS, Cook EF, et al. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:828–33. 10.1001/archinte.167.8.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Volandes AE, Levin TT, Slovin S, et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention-postintervention study. Cancer 2012;118:4331–8. 10.1002/cncr.27423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b2159 10.1136/bmj.b2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis AD, et al. Use of video decision aids to promote advance care planning in Hilo, Hawai'i. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1035–40. 10.1007/s11606-016-3730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. About Us. http://www.pcori.org/about-us (accessed 21 Mar 2017).

- 52. Major Surgery. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 2015.

- 53. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Aslakson RA, Schuster AL, Miller J, et al. An environmental scan of advance care planning decision AIDS for patients undergoing major surgery: a study protocol. Patient 2014;7:207–17. 10.1007/s40271-014-0046-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schuster AL, Aslakson RA, Bridges JF. Creating an advance-care-planning decision aid for high-risk surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:32 10.1186/1472-684X-13-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aslakson RA, Schuster AL, Reardon J, et al. Promoting perioperative advance care planning: a systematic review of advance care planning decision aids. J Comp Eff Res 2015;4:615–50. 10.2217/cer.15.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mitchell IA, Schuster AL, Lynch T, et al. Why don't end-of-life conversations go viral? A review of videos on YouTube. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015:bmjspcare-2014-000805 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Roter D, Larson S. The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns 2002;46:243–51. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1087–110. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haberle TH, Shinkunas LA, Erekson ZD, et al. Goals of care among hospitalized patients: a validation study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2011;28:335–41. 10.1177/1049909110388505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Roter DL, Erby LH, Rimal RN, et al. Empowering women's prenatal communication: does literacy matter? J Health Commun 2015;20(Suppl 2):60–8. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1080330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roter D, Ellington L, Erby LH, et al. The genetic counseling video project (GCVP): models of practice. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2006;142C:209–20. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Roter DL, Erby LH, Larson S, et al. Assessing oral literacy demand in genetic counseling dialogue: preliminary test of a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:1442–57. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Suchman AL, Roter D, Green M, et al. Physician satisfaction with primary care office visits. Collaborative Study Group of the american academy on physician and patient. Med Care 1993;31:1083–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Grusec JE. Social learning theory and development psychology: the legacy of Robert Sears and Albert Bandura. Dev Psychol 1992;28:776–86. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Steinwachs DM, Roter DL, Skinner EA, et al. A web-based program to empower patients who have schizophrenia to discuss quality of care with mental health providers. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:1296–302. 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stata Statistical Software: release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pecanac KE, Kehler JM, Brasel KJ, et al. It's big surgery: preoperative expressions of risk, responsibility, and commitment to treatment after high-risk operations. Ann Surg 2014;259:458–63. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–78. 10.1056/NEJMoa063446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.