Abstract

Purpose

To assess surgical practice patterns among the American Glaucoma Society (AGS) membership.

Methods

An anonymous online survey evaluating the use of glaucoma surgeries in various clinical settings was redistributed to AGS members. Survey responses were compared with prior results from 1996, 2002, and 2008 to determine shifts in surgical practice patterns. Questions were added to assess the preferred approach to primary incisional glaucoma surgery and phacoemulsification combined with glaucoma surgery.

Results

A total of 252 of 1,091 (23%) subscribers to the AGS-net participated in the survey. Percentage use (mean ± SD) of trabeculectomy with mitomycin C (MMC), glaucoma drainage device (GDD), and minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) as an initial surgery in patients with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) was 59% ± 30%, 23% ± 23%, and 14% ± 20%, respectively. Phacoemulsification cataract extraction alone was the preferred surgical approach in 44% ± 32% of patients with POAG and visually significant cataract, and phacoemulsification cataract extraction was combined with trabeculectomy with MMC in 24% ± 23%, with MIGS in 22% ± 27%, and with GDD in 9% ± 14%. While trabeculectomy was selected most frequently to surgically manage glaucoma in 8 of 8 clinical settings in 1996, GDD was preferred in 7 of 8 clinical settings in 2016.

Conclusions

The use of GDD has increased and that of trabeculectomy has concurrently decreased over the past 2 decades. Trabeculectomy with MMC is the most popular primary incisional surgery when performed alone or in combination with phacoemulsification cataract extraction. Surgeons frequently manage coexistent cataract and glaucoma with cataract extraction alone, rather than as a combined cataract and glaucoma procedure.

Keywords: glaucoma drainage implant, glaucoma filtering surgery, minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery, mitomycin C, trabeculectomy

Introduction

Several shifts in practice patterns have emerged as the surgical management of glaucoma evolves. Fornix-based conjunctival flaps with diffuse application of lower doses of mitomycin C (MMC) are commonly employed and associated with more favorable bleb morphology and lower rates of late bleb-related complications.1,2 Although trabeculectomy remains the most frequently performed glaucoma surgery in the United States, glaucoma drainage device (GDD) use has increased.3 Many new minimally- or micro-invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) have recently been introduced into clinical practice.4

Surgical trends in glaucoma have been described and quantified through examinations of Medicare claims data and surveys of the American Glaucoma Society (AGS) membership.3,5-7 Ours is the fourth in a series of surveys evaluating practice preferences in glaucoma surgery among AGS members over the past 20 years. The purpose of the current study is to evaluate changes in practice patterns based on a comparison of results with those from prior surveys. The use of phacoemulsification and MIGS in patients with glaucoma is also assessed with a new survey question.

Methods

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami and the AGS Research Committee. An anonymous survey was created using the online services provided by surveymonkey.com, and a link was distributed via e-mail to AGS members who subscribe to the AGS-net. The survey was available for 6 weeks beginning on March 15, 2016.

The survey was formatted in a manner similar to prior iterations. Participants were first asked whether they primarily practice in academic or private settings and how many years ago they completed their glaucoma fellowship training. Surgeons were then asked about the percentage of patients in whom they perform certain procedures, including trabeculectomy with and without antifibrotics and GDDs. A total of 12 different clinical scenarios were presented. Repeated questions included those regarding the procedure of choice in patients with prior failed trabeculectomy, prior extracapsular (ECCE) or intracapsular cataract extraction (ICCE), prior phacoemulsification cataract extraction, prior penetrating keratoplasty (PKP), prior scleral buckle (SB), prior pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), uveitis, and neovascular glaucoma. Participants were given the option to free text the duration and concentration of MMC, type of GDD, and type of MIGS, or to list “Other” procedures where applicable. Two additional scenarios were repeated asking about the use of antifibrotics when performing trabeculectomy as a first incisional surgery and combined phacoemulsification with trabeculectomy. A clinical scenario was introduced in 2008 inquiring about the choice of surgery in a phakic patient with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) without prior incisional surgery, and MIGS was added as an answer choice in the present survey. A similar question was included regarding initial surgical options for a phakic, unoperated patient with POAG and a visually significant cataract, which also provided MIGS as an answer choice.

Data were compared with results from the 1996, 2002, and 2008 surveys for repeated clinical scenarios. Of note, the percentages did not add up to 100 in all cases due to rounding and free-texted responses in the “Other” category for which specific percentage use was not specified by respondents. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the significance of differences among three means, and the two sample t-test was used to assess statistical significance of the difference between two means. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 252 of 1,091 (23%) subscribers to the AGS-net participated in the survey. Fifty-nine percent of survey participants practiced in the private setting, while 41% practiced in the academic setting. Most survey respondents completed their glaucoma fellowship training either over 20 years ago (33%) or between 1 and 5 years ago (29%).

Mitomycin C use has increased steadily since 1996 in the settings of primary trabeculectomy and combined phacoemulsification and trabeculectomy, while 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and no antifibrotic are uncommonly used in 2016 (Table 1). In 2016, the most popular dosage of MMC for primary trabeculectomy remained 0.4 mg/mL (range, 0.2 to 0.5 mg/mL), used by 48% of survey participants versus 37% of survey participants in 2008. A 2 minute application was the most popular duration of MMC (range, 45 seconds to 4.5 minutes) during primary trabeculectomy in 2016, used by 33% of respondents versus 45% of respondents in 2008. Thirty-one percent of survey participants in 2016 indicated that they administer MMC intraoperatively via a subconjunctival injection, rather than via direct sponge application to the scleral bed, during primary trabeculectomy. This method of antifibrotic delivery was not mentioned by surgeons in previous surveys.

Table 1. Mean (SD) percentage use of antifibrotics during primary trabeculectomy and phacoemulsification/trabeculectomy.

| 1996 | 2002 | 2008 | 2016 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 45 (41) | 68 (37) | 84 (26) | 97 (12) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 29 (39) | 39 (37) | 5 (16) | 0.8 (6) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 23 (33) | 3 (10) | 0.7 (7) | <0.001† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 7 (19) | 0.9 (7) | <0.001‡ |

| Phacoemulsification/trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 65 (43) | 83 (33) | 90 (24) | 99 (8) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 18 (34) | 15 (35) | 2 (10) | 0.3 (2) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 6 (20) | 1 (6) | < 0.1 | 0.009† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 6 (21) | 1 (8) | 0.001‡ |

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil; IO = intraoperative; MMC = mitomycin C; PO = postoperative; SD = standard deviation.

Data are presented as average percentage (standard deviation of percentage). Percentage in each category may not sum to 100% because of rounding and free-texted responses in the “Other” category for which specific percentage use was not reported.

Answer choice not presented in survey.

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences among three means.

Student t-test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between two means.

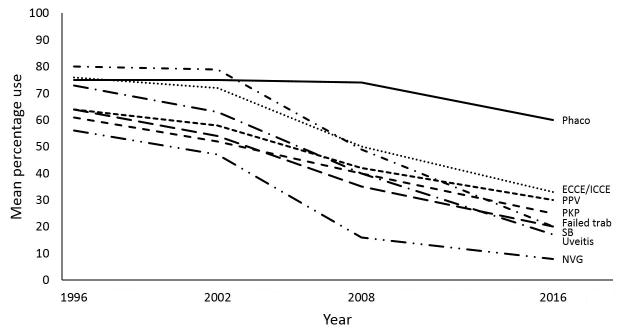

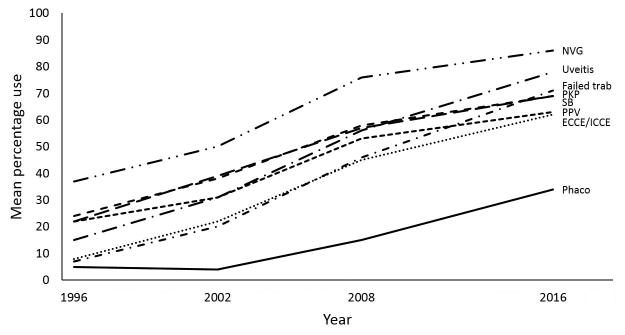

The mean percentage use of glaucoma procedures in various clinical settings is listed in Table 2. In 1996, trabeculectomy with MMC was the preferred surgical approach in all 8 scenarios that were repeated in 3 subsequent surveys. The overall mean percentage use of trabeculectomy has declined since 1996, while that of GDD has increased in all scenarios (Figures 1 and 2). In 2016, GDD was favored over trabeculectomy in all relevant settings except in patients with no prior incisional surgery and those with prior phacoemulsification only. Among surgeons who indicated a GDD type, the Baerveldt glaucoma implant (Abbott Medical Optics Inc., Santa Ana, CA, USA) was used more often than the Ahmed glaucoma valve (New World Medical Inc., Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA) for patients with prior ECCE or ICCE (cited by 70% of surgeons), prior phacoemulsification (68% of surgeons), prior failed trabeculectomy (67% of surgeons), and prior PPV (67% of surgeons). The Ahmed glaucoma valve was used by 88%, 83%, 68%, and 62% of surgeons for patients with uveitis, neovascular glaucoma, prior PKP, and prior SB, respectively.

Table 2. Mean (SD) percentage use of glaucoma procedures by American Glaucoma Society members in various clinical settings.

| 1996 | 2002 | 2008 | 2016 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior trabeculectomy | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 80 (31) | 79 (30) | 49 (33) | 20 (24) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 13 (27) | 16 (32) | 1 (7) | 0.1 (0.7) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 5 (18) | 0.2 (2) | 0 | <0.001† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 1 (6) | 0 | 0.065‡ |

| GDD | 7 (12) | 20 (28) | 46 (34) | 71 (28) | <0.001† |

| MIGS | * | * | * | 2 (5) | N/A |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 1 (4) | N/A |

| Prior ECCE/ICCE | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 76 (33) | 72 (35) | 50 (37) | 33 (33) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 15 (29) | 15 (31) | 1 (4) | 0.1 (0.9) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 7 (20) | 0.2 (3) | 0.7 (8) | <0.001† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 2 (11) | 0 | 0.044‡ |

| GDD | 8 (15) | 22 (30) | 45 (37) | 62 (33) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 1 (3) | N/A |

| Prior phacoemulsification | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 75 (35) | 75 (33) | 74 (32) | 60 (32) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 17 (32) | 23 (42) | 2 (9) | 0.7 (7) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 12 (26) | 1 (6) | 0.7 (8) | <0.001† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 3 (14) | 0.1 (0.8) | 0.022‡ |

| GDD | 5 (13) | 4 (13) | 15 (24) | 34 (30) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 0.4 (2) | N/A |

| Prior PKP | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 61 (38) | 52 (41) | 40 (34) | 25 (30) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 10 (24) | 9 (22) | 0.1 (1) | 0 | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 4 (15) | 0 | 0.7 (8) | 0.002† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 1 (4) | < 0.1 | 0.008‡ |

| GDD | 24 (30) | 38 (39) | 58 (34) | 69 (33) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 3 (11) | N/A |

| Prior SB | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 64 (37) | 54 (42) | 35 (35) | 20 (30) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 12 (28) | 12 (26) | 1 (5) | 0 | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 3 (17) | 0.1 (1) | 0.4 (4) | 0.015† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 0.5 (5) | 0 | 0.27‡ |

| GDD | 22 (29) | 39 (40) | 57 (36) | 69 (34) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 7 (16) | N/A |

| Prior PPV | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 64 (36) | 58 (40) | 42 (33) | 30 (29) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 12 (27) | 11 (28) | 1 (9) | 0 | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 3 (12) | 0.1 (1) | 0.6 (7) | 0.009† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 0.2 (1) | 0 | 0.27‡ |

| GDD | 22 (30) | 31 (37) | 53 (34) | 63 (32) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 2 (6) | N/A |

| Uveitis | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 73 (33) | 63 (39) | 40 (34) | 17 (23) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 12 (26) | 14 (32) | 1 (9) | < 0.1 | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 5 (18) | 0.1 (1) | 0.7 (7) | <0.001† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 1 (6) | < 0.1 | 0.075‡ |

| GDD | 15 (26) | 31 (37) | 56 (34) | 78 (26) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 0.4 (2) | N/A |

| Neovascular glaucoma | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | 56 (40) | 47 (42) | 16 (22) | 8 (17) | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | 6 (20) | 12 (31) | 0.1 (0.4) | 0 | <0.001† |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | 3 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0.003† |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| GDD | 37 (38) | 50 (42) | 76 (28) | 86 (22) | <0.001† |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 5 (14) | N/A |

| POAG without prior incisional surgery | |||||

| Trabeculectomy | |||||

| MMC | * | * | 74 (31) | 59 (30) | <0.001‡ |

| 5-FU (IO + PO) | * | * | 4 (14) | 0.6 (6) | 0.001‡ |

| 5-FU (IO only) | * | * | 3 (10) | 0.6 (7) | 0.017‡ |

| No antifibrotic | * | * | 4 (16) | 0.2 (1) | 0.009‡ |

| GDD | * | * | 11 (22) | 23 (23) | <0.001 |

| MIGS | * | * | * | 14 (20) | N/A |

| CPC# | * | * | * | 0.4 (2) | N/A |

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil; CPC = cyclophotocoagulation (of any type); ECCE = extracapsular cataract extraction; GDD = glaucoma drainage device; ICCE = intracapsular cataract extraction; IO = intraoperative; MIGS = minimally invasive glaucoma surgery; MMC = mitomycin C; N/A = not applicable; PKP = penetrating keratoplasty; PO = postoperative; POAG = primary open angle glaucoma; PPV = pars plana vitrectomy; SB = scleral buckle; SD = standard deviation.

Data are presented as average percentage (standard deviation of percentage). Percentage in each category may not sum to 100% because of rounding and free-texted responses in the “Other” category for which specific percentage use was not reported.

Answer choice not presented in survey.

One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the statistical significance of the differences among three means.

Student t-test was used to assess the statistical significance of the difference between two means. The Satterthwaite unpooled variance approximation was used when appropriate.

Cyclophotocoagulation (of any type) was a frequently free-texted response and is therefore included in the table.

Figure 1.

Mean percentage use of trabeculectomy with mitomycin C in 8 clinical settings, 1996-2016.

Figure 2.

Mean percentage use of glaucoma drainage devices in 8 clinical settings, 1996-2016.

In a question first introduced in 2008 regarding the preferred surgical approach in a POAG patient without previous incisional surgery, the mean percentage use of trabeculectomy with MMC fell from 74% ± 31% in 2008 to 59% ± 30% in 2016, and the mean percentage use of GDD increased from 11% ± 22% in 2008 to 23% ± 23% in 2016. MIGS was added as an answer choice in 2016, and was used in 14% ± 20% of patients. As was the case in other scenarios, the mean percentage use of trabeculectomy with intraoperative and postoperative 5-FU, intraoperative 5-FU only, and no antifibrotic was negligible (less than 1%).

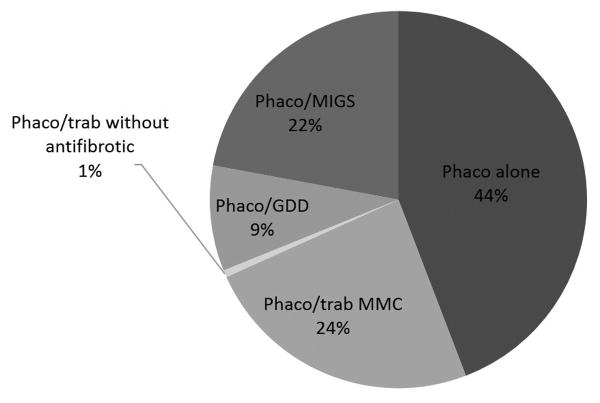

A new question regarding the preferred approach to a POAG patient without prior incisional surgery and with a visually significant cataract was presented in the 2016 survey (Figure 3). Surgeons performed phacoemulsification cataract surgery alone in 44% ± 32% of patients, versus phacoemulsification combined with trabeculectomy using MMC, phacoemulsification combined with MIGS, and phacoemulsification combined with GDD in 24% ± 23%, 22% ± 27%, and 9% ± 14% of patients, respectively. Trabeculectomy using 5-FU intraoperatively and postoperatively and 5-FU intraoperatively only was selected in 0% of cases, and trabeculectomy without antifibrotic was combined with phacoemulsification in 1% of cases on average. Among surgeons who indicated their preferred MIGS procedures, the trabecular microbypass stent (iStent, Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, USA) was the most popular (cited by 76% of respondents), followed by ab interno trabeculectomy (Trabectome, NeoMedix Inc., Tustin, CA, USA; 21% of respondents), and endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP; 18% of respondents). Less frequently mentioned were gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT; 7% of respondents), canaloplasty (3% of respondents), and TRAB360 (Sight Sciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA; 3% of respondents). Many surgeons reported using more than one type of MIGS procedure in their practices.

Figure 3.

Mean percentage use of phacoemulsification cataract surgery alone versus as a combined procedure in an unoperated eye with primary open angle glaucoma and a visually significant cataract. GDD = glaucoma drainage device; MIGS = minimally invasive glaucoma surgery; MMC = mitomycin C; phaco = phacoemulsification cataract surgery; trab = trabeculectomy.

Surgeons were given the option to indicate an “Other” procedure if their favored surgical approaches were not listed as answer choices in each question. An Ex-PRESS Shunt (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX) was selected by a small percentage (2%) of surgeons as a primary procedure in a phakic patient with POAG. Twelve percent of survey respondents indicated that they perform bleb needling or trabeculectomy revision in the setting of a prior failed trabeculectomy.

Cyclophotocoagulation (CPC) using either a transscleral or endoscopic approach was commonly mentioned as an “Other” procedure by surgeons in the 2016 survey, and results are included in Table 2. Mean percentage use of CPC was highest for patients with prior SB (7% ± 16%), neovascular glaucoma (5% ± 14%), and prior PKP (3% ± 11%).

A sub-analysis of survey results by practice setting revealed no statistically significant differences in mean percentage use of any given surgical technique in any clinical scenario between surgeons in academic and private practice. On the other hand, statistically significant differences in mean percentage use of trabeculectomy with MMC and GDD were observed among surgeons with 0-10, 11 to 20, and more than 20 years of experience in the majority of clinical scenarios. Mean percentage use of trabeculectomy with MMC was significantly higher among older than younger surgeons for patients with prior trabeculectomy (P < 0.001), prior ECCE/ICCE (P = 0.021), prior phacoemulsification (P < 0.001), prior PKP (P = 0.017), uveitis (P = 0.002), neovascular glaucoma (P = 0.030), and POAG without incisional surgery (P < 0.001), while that of GDD was more common among younger than older surgeons for the same scenarios (P-values of 0.002, 0.022, 0.001, 0.006, 0.002, 0.001, and < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, MIGS was used more often by younger than older surgeons in nonoperated eyes with POAG (P = 0.005).

Discussion

Glaucoma surgical practice patterns may be influenced by several factors. Refinement in surgical technique of existing procedures contributes to increased efficiency and decreased complication rates. Novel procedures targeting different aspects of aqueous production and outflow have been introduced into clinical practice. Additional data from randomized clinical trials describing the safety and efficacy of glaucoma operations have also become available.

Surveys of the AGS membership are a valuable tool to assess practice preferences.5-15 The AGS membership consists of ophthalmologists who have received subspecialty fellowship training in glaucoma. AGS members were surveyed previously in 1996, 2002, and 2008 regarding preferred surgical modalities in various clinical settings.5-7 Redistribution of the survey in 2016 allowed for evaluation of trends evolving over 2 decades.

Trabeculectomy and GDD have traditionally been the procedures used to manage medically uncontrolled glaucoma. Prior surveys demonstrated that the proportion of cases in which trabeculectomy is used has declined with a concomitant increase in the number of GDDs, and the present survey shows a continuation of this trend. These results mirror those from a study of Medicare claims data from 1994 to 2012.3 In the 2016 survey, we found that older surgeons were more likely to use trabeculectomy with MMC in most clinical settings, while younger surgeons more often preferred GDD. This may reflect recent trends observed among residency and fellowship training programs toward the use of GDD and away from trabeculectomy.16,17

Mitomycin C has consistently gained favor over the past 20 years as the antifibrotic of choice for trabeculectomy when performed alone or as a combined procedure with phacoemulsification cataract surgery. A decrease in the dosage and duration of MMC has likely been prompted by concerns about bleb-related infection and hypotony.18-20 Interestingly, 31% of glaucoma surgeons in 2016 indicated that they administer MMC via subconjunctival injection when performing primary trabeculectomy, rather than applying MMC-soaked sponges directly to the scleral bed. A retrospective review comparing intra-Tenon injection and sponge application of MMC during trabeculectomy showed better IOP control with fewer glaucoma medications at 3 years in the injection group with no difference in complications other than more frequent tense, vascularized blebs in the sponge group.21 Lower doses, precise control of dosage, and formation of more diffuse blebs are potential advantages of the injection technique, which has not yet been evaluated in prospective fashion.

Glaucoma drainage devices were favored in 7 of 8 clinical settings in 2016, and in none of the same 8 clinical settings in 1996. Glaucoma drainage devices have traditionally been used in high-risk glaucomas, including uveitic and neovascular glaucoma. While the mean percentage use of GDD and trabeculectomy with MMC for patients with prior failed trabeculectomy were comparable in 2008 (46% ± 34% and 49% ± 33%, respectively), GDD use (71% ± 28%) surpassed that of trabeculectomy with MMC (20% ± 24%) in 2016. Although trabeculectomy with MMC remains the procedure of choice for patients with prior phacoemulsification in 2016, the use of GDD in this setting has increased 7-fold in the past 20 years. The Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) Study was a multicenter trial that prospectively randomized patients with prior cataract surgery and/or trabeculectomy to receive either trabeculectomy with MMC or 350-mm2 Baerveldt glaucoma implant surgery. At 5 years postoperatively, patients who underwent Baerveldt glaucoma implant surgery had comparable intraocular pressures (IOP), higher success rates, and lower rates of reoperation compared to patients who underwent trabeculectomy with MMC.22 The TVT Study likely contributed to the dramatic shift in surgical practice patterns for low-risk eyes with POAG that occurred between the 2008 and 2016 surveys. Indeed, a different survey assessing the clinical impact of randomized, multicenter glaucoma trials showed that the TVT Study prompted the majority of AGS members (59%) to perform GDD rather than repeat trabeculectomy in eyes with previously failed trabeculectomy.15 Other factors, including varying emphasis on different surgical techniques among residency and fellowship training programs and changes in reimbursement schedules, have likely influenced shifts in practice preferences but were not specifically evaluated in our survey.

Transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCPC) has historically been reserved for blind, painful eyes or eyes with low visual potential due to its potential adverse effects, including chronic hypotony, vision loss, and phthisis. Eyes with extensive conjunctival scarring from prior surgery may be more amenable to TSCPC rather than additional incisional glaucoma surgery. Ciliary body ablation under direct visualization using ECP can be combined with phacoemulsification cataract surgery, allowing for earlier use in eyes with less severe disease. Reported success rates following TSCPC and ECP have ranged from 37% to 80% and from 74% to 90%, respectively, with at least 1 year of follow-up.23 The recently introduced micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (MP-TSCPC) delivers laser energy via repetitive, short duration pulses with intervening rest periods rather than in continuous fashion as in traditional TSCPC. Early studies of MP-TSCPC suggest success rates over 70%, but long-term results are not available for this novel procedure.24,25 In our survey, surgeons indicated that they used CPC of any method most frequently for eyes with prior SB, neovascular glaucoma, and prior PKP. Future surveys can assess whether the availability of ECP and MP-TSCPC will shift the use of CPC toward more low-risk eyes.

Surgical options for glaucoma have expanded with the introduction of several MIGS procedures in recent years.4 Minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery has been defined by the presence of 5 features: an ab interno microincision, minimal tissue trauma, at least modest efficacy, high safety, and rapid visual recovery.26 These surgeries can be performed alone or in combination with phacoemulsification cataract surgery using the same clear corneal incision. The conjunctiva is spared, which facilitates future incisional glaucoma surgery if adequate reduction in IOP is not achieved after MIGS.

The iStent and Trabectome, both of which are FDA-approved, were the most popular MIGS procedures selected in the 2016 survey. The iStent Study Group performed the largest prospective randomized controlled trial to date comparing single iStent implantation plus phacoemulsification cataract extraction versus phacoemulsification cataract extraction alone. At 2 years postoperatively, more patients in the iStent group had a sustained reduction in IOP ≤ 21 mm Hg without glaucoma medications when compared to controls (61% versus 50%, respectively; p = 0.036).27 A meta-analysis of prospective and retrospective case series evaluating the Trabectome found an overall success rate (IOP ≤ 21 mm Hg with a 20% decrease from baseline without additional glaucoma surgery) of 66% at 2 years after Trabectome alone or combined with phacoemulsification.28 Both the iStent and Trabectome are associated with a favorable safety profile, but are generally reserved for patients with mild-to-moderate glaucoma given their inability to produce very low IOP due to resistance in distal outflow pathways.

Cataract and glaucoma frequently coexist in elderly patients. Cataract surgery alone has been shown to reduce IOP in eyes with ocular hypertension and glaucoma.29,30 A new survey question in 2016 evaluated the preferred approach to managing a visually significant cataract in a patient with POAG and without prior surgery. Our results suggest that glaucoma surgeons regularly perform phacoemulsification cataract surgery alone (44% ± 32%) in such patients. Surgeons also frequently combined phacoemulsification with trabeculectomy using MMC (24% ± 23%) and MIGS (22% ± 27%) in this clinical scenario.

The primary glaucoma procedure of choice in patients with POAG without prior ocular surgery was first introduced as a survey question in 2008. Trabeculectomy with MMC remains the most popular operation, but the use of GDD has since doubled. A retrospective study comparing the effectiveness of Baerveldt glaucoma implant surgery and trabeculectomy with MMC in eyes without prior incisional surgery suggested similar success and complication rates at 3 years.31 This topic is currently under evaluation in the Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (PTVT) Study, a multicenter randomized clinical trial.32

Our study has several limitations. Recent expansion of the AGS membership was reflected in the larger absolute number of survey respondents in 2016, though the percentage response rate remained low and similar to prior published surveys of AGS members.7,15 The anonymous nature of the survey did not allow us to compare characteristics of AGS members who did and did not participate to assess for nonresponse bias. Our target audience of fellowship-trained AGS members may not be representative of all surgeons who perform glaucoma surgery, which could also affect the generalizability of results. In order to maintain consistent phrasing and allow comparison of results across surveys, severity of disease was not specified in the new survey and only a small number of clinical scenarios was presented.

The surgical management of glaucoma is changing, and our survey results suggest a continued trend away from trabeculectomy and toward GDD in most clinical settings. Glaucoma drainage devices are being used more frequently in eyes at low risk for filtration failure. Cataract surgery and MIGS, either alone or in combination, are developing their roles in the care of glaucoma patients requiring surgical intervention. Future surveys will help evaluate these and new trends as further advances in glaucoma surgery are produced.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial interest in the content of this article.

References

- 1.Wells AP, Cordeiro MF, Bunce C, et al. Cystic bleb formation and related complications in limbus- versus fornix-based conjunctival flaps in pediatric and young adult trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:2192–2197. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00800-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solus JF, Jampel HD, Tracey PA, et al. Comparison of limbus-based and fornix-based trabeculectomy: success, bleb-related complications, and bleb morphology. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora KS, Robin AL, Corcoran KJ, et al. Use of Various Glaucoma Surgeries and Procedures in Medicare Beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology. 2015 Aug;122(8):1615–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis BA, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Novel glaucoma procedures: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(7):1466–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen PP, Yamamoto T, Sawada A, et al. Use of antifibrosis agents and glaucoma drainage devices in the American and Japanese Glaucoma Societies. J Glaucoma. 1997;6:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi AB, Parrish RK, 2nd, Feuer WF. 2002 Survey of the American Glaucoma Society: practice preferences for glaucoma surgery and antifibrotic use. J Glaucoma. 2005;14:172–174. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000151684.12033.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai MA, Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, et al. Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: a survey of the American Glaucoma Society in 2008. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011 May-Jun;42(3):202–8. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110224-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz AL. Argon Laser Trabeculoplasty in Glaucoma: What's Happening (Survey Results of American Glaucoma Society Members) J Glaucoma. 1993 Winter;2(4):329–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PP, Rao S, Azen S, et al. Time parameters for glaucoma procedures. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Jun;112(6):755–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180053034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wand M, Quintiliani R, Robinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis in eyes with filtration blebs: survey of glaucoma specialists, microbiological study, and recommendations. J Glaucoma. 1995 Apr;4(2):103–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidorf JM, Baker ND, Derick R. Treatment of the fellow eye in acute angle-closure glaucoma: a case report and survey of members of the American Glaucoma Society. J Glaucoma. 1996 Aug;5(4):228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvo EC, Jr, Luntz MH, Medow NB. Use of viscoelastics post-trabeculectomy: a survey of members of the American Glaucoma Society. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999 Apr;30(4):271–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds AC, Skuta GL, Monlux R, et al. Management of blebitis by members of the American Glaucoma Society: a survey. J Glaucoma. 2001 Aug;10(4):340–7. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jampel HD, Parekh P, Johnson E, et al. Preferences for eye drop characteristics among glaucoma specialists: a willingness-to-pay analysis. J Glaucoma. 2005 Apr;14(2):151–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000151879.14855.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panarelli JF, Banitt MR, Sidoti PA, et al. Clinical impact of 8 prospective, randomized, multicenter glaucoma trials. J Glaucoma. 2015 Jan;24(1):64–8. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318295200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chadha N, Liu J, Teng CC. Resident and Fellow Glaucoma Surgical Experience Following the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study. Ophthalmology. 2015 Sep;122(9):1953–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gedde SJ, Vinod K. Resident surgical training in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016 Mar;27(2):151–7. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs DJ, Leng T, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Delayed-onset bleb-associated endophthalmitis: presentation and outcome by culture result. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:739–44. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S17975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jampel HD, Solus JF, Tracey PA, et al. Outcomes and bleb-related complications of trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology. 2012 Apr;119(4):712–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto T, Sawada A, Mayama C, et al. Collaborative Bleb-Related Infection Incidence and Treatment Study Group. The 5-year incidence of bleb-related infection and its risk factors after filtering surgeries with adjunctive mitomycin C: collaborative bleb-related infection incidence and treatment study 2. Ophthalmology. 2014 May;121(5):1001–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim MC, Paul T, Tong MG, et al. A comparison of trabeculectomy surgery outcomes with mitomycin-C applied by intra-Tenon injection versus sponge method. American Glaucoma Society; San Francisco, CA: Mar 2, 2013. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, et al. Tube versus Trabeculectomy Study Group. Treatment outcomes in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study after five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:789–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin SC. Endoscopic and transscleral cyclophotocoagulation for the treatment of refractory glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2008 Apr-May;17(3):238–47. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815f2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aquino MC, Barton K, Tan AM, et al. Micropulse versus continuous wave transscleral diode cyclophotocoagulation in refractory glaucoma: a randomized exploratory study. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015 Jan-Feb;43(1):40–6. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuchar S, Moster MR, Reamer CB, et al. Treatment outcomes of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in advanced glaucoma. Lasers Med Sci. 2016 Feb;31(2):393–6. doi: 10.1007/s10103-015-1856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saheb H, Ahmed II. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012 Mar;23(2):96–104. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff1e7. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craven ER, Katz LJ, Wells JM, et al. iStent Study Group. Cataract surgery with trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation in patients with mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma and cataract: two-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012 Aug;38(8):1339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplowitz K, Bussel II, Honkanen R, et al. Review and meta-analysis of ab-interno trabeculectomy outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(5):594–600. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansberger SL, Gordon MO, Jampel H, et al. Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. Reduction in intraocular pressure after cataract extraction: the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2012 Sep;119(9):1826–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen PP, Lin SC, Junk AK, et al. The effect of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in glaucoma patients: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1294–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panarelli JF, Banitt MR, Gedde SJ, et al. A Retrospective Comparison of Primary Baerveldt Implantation versus Trabeculectomy with Mitomycin C. Ophthalmology. 2016 Apr;123(4):789–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ClinicalTrials.gov. Primary Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study. [Accessed July 3, 2016]; Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00666237.