Abstract

The yeast Saccharomyces are widely used to test ecological and evolutionary hypotheses. A large number of nuclear genomic DNA sequences are available, but mitochondrial genomic data are insufficient. We completed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequencing from Illumina MiSeq reads for all Saccharomyces species. All are circularly mapped molecules decreasing in size with phylogenetic distance from Saccharomyces cerevisiae but with similar gene content including regulatory and selfish elements like origins of replication, introns, free-standing open reading frames or GC clusters. Their most profound feature is species-specific alteration in gene order. The genetic code slightly differs from well-established yeast mitochondrial code as GUG is used rarely as the translation start and CGA and CGC code for arginine. The multilocus phylogeny, inferred from mtDNA, does not correlate with the trees derived from nuclear genes. mtDNA data demonstrate that Saccharomyces cariocanus should be assigned as a separate species and Saccharomyces bayanus CBS 380T should not be considered as a distinct species due to mtDNA nearly identical to Saccharomyces uvarum mtDNA. Apparently, comparison of mtDNAs should not be neglected in genomic studies as it is an important tool to understand the origin and evolutionary history of some yeast species.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA, yeasts, genetic code, introns, phylogeny

1. Introduction

Because of advanced genetics and simple and easy production of mutants, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the most widely used unicellular eukaryotic model organism. It is the best known member of the genus Saccharomyces with accepted species: S. cerevisiae, S. cariocanus, S. paradoxus, S. mikatae, S. kudriavzevii, S. arboricolus, S. bayanus var. bayanus, S. bayanus var. uvarum and S. pastorianus.1 These yeast species are involved in fermenting sugars and produce enormous amounts of ethanol; however, most of the strains used to manufacture beer, wine or fuel ethanol are interspecific hybrids.2–4 Therefore, the taxonomic classifications of alloploid species S. pastorianus and S. bayanus do not agree with the outcome of whole genome sequencing.4,5

These discrepancies arose exclusively from the comparison of nuclear chromosomes. The data for much smaller mitochondrial genomes encoding only eight proteins required for oxidative phosphorylation, one ribosomal protein, two ribosomal RNAs (rRNA), the RNA component of RNase P, and a set of 24 tRNA genes were largely overlooked or unavailable.6,7 Despite large numbers of nuclear genome sequences now accessible for different Saccharomyces species and isolates4,8–10 completed mitochondrial genome sequences are known only for S. cerevisiae,6S. paradoxus,11S. pastorianus12 and Saccharomyces eubayanus.5 Recently, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from S. bayanus and S. pastorianus were sequenced but not annotated.13 The problem is associated with the short DNA reads (100–200 nt) generated by the most next-generation sequencing platforms in genomic studies, especially by Illumina MiSeq.14–17 This approach can be used routinely for sequencing mtDNA from different yeast species18 but not from many species of Saccharomyces.9,16,17 Their mitochondrial genomes can be assembled only by combination of different gap-filling programmes19 or by extensive manual editing.20,21

The purpose of this work was to obtain complete mitochondrial genomes for all species assigned to Saccharomyces with the aim of comparing their genetic content to that of S. cerevisiae, as many different Saccharomyces mtDNAs can substitute, to some extent, for the original molecule in S. cerevisiae.22

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Yeast strains and mtDNA sequencing

Sequenced strains are being used as taxonomic standards (type strains)1 in whole genome studies,4,10 or their mtDNA is being transferred to S. cerevisiae in order to prepare xenomitochondrial cybrids.22 Their origin is described in detail in reference.22Saccharomyces arboricolus NRRL Y-63701 and S. pastorianus NRRL Y-27171NT were kindly provided by the Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, US Department of Agriculture, Peoria, IL, USA. Yeast cells were grown at 28 °C in YPD medium (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract and 1% peptone). The mtDNA was purified mainly by differential centrifugation23 or alternatively by bisbenzimide/CsCl buoyant density centrifugation.24,25 mtDNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) and sequenced with average genome coverage between 176 and 3,698× on an Illumina MiSeq sequencing system using a MiSeq Reagent kit v3 (Illumina) with reads 2 × 100 bp in length. The sequencing summary is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequencing summary

| Strain | Paired reads | Average length | Coverage Xa | DNA | Contigs/nts | Coverage % | mtDNA size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae NRRL Y-12632T | 2,578,141 | 147 | 4,234 | Df | 5/87,765 | 98 | 89,507 |

| S. paradoxus CBS 2908 | 1,580,034 | 96 | 2,283 | Gr | 5/66,147 | 99.6 | 66,436 |

| S. paradoxus CBS 7400 | 2,242,369 | 96 | 3,014 | Gr | 2/70,538 | 98.7 | 71,419 |

| S. cariocanus CBS 7994T | 1,897,384 | 96 | 2,354 | Gr | 10/75,729 | 98 | 77,380 |

| S. mikatae CBS 8839T | 413,405 | 189 | 917 | Df | 2/85,137 | 99.9 | 85,211 |

| S. kudriavzevii CBS 8840T | 2,259,934 | 96 | 2,692 | Gr | 3/80,240 | 99.5 | 80,588 |

| S. arboricolus NRRL Y-63701 | 535,328 | 139 | 1,073 | Df | 9/70,040 | 101 | 69,363 |

| S. pastorianus NRRL Y-27171T | 555,165 | 158 | 1,271 | Df | 7/68,800 | 99.7 | 69,019 |

| S. bayanus CBS 380T | 1,221,753 | 85 | 1,604 | Gr | 1/64,742 | 100 | 64,736 |

| S. uvarum CBS 395Tb | 25,298,820 | 36 | 14,059 | – | 34/51,450 | 79.4 | 64,779 |

2.2. mtDNA assembly and annotation

Sequencing provided several hundred megabytes of data in more than one million reads, 90–190 nt long. Paired reads were trimmed, short reads (often with erroneous sequences) removed and assembled into individual contigs using CLC Genomics Workbench 9.5 (Qiagen, Hilden, DE). From thousands of contigs with an average size of ∼1,500 nt, only those containing mtDNA by BLASTN comparison to already known mtDNA from related yeasts (S. cerevisiae NC001224; S. paradoxus JQ862335, S. pastorianus EU852811) were selected. Individual contigs with mtDNA segments were assembled into a single molecule using the Vector NTI v.9.0 (v.10) software package from InforMax, Inc. Overall, 1–10 contigs were obtained covering 98–101% of the entire sequence, depending on the purification method (Table 1). All mtDNAs were interrupted in the redundant intergenic regions, mostly in the origins of replication (ori ∼270 nt) and GC clusters. Contigs were manually edited and linked together from individual reads as previously reported.21 Some gaps were sealed by direct sequencing using fluorescent dye terminator sequencing chemistry. Assembly of S. mikatae CBS 8839 (NRRL Y-27341T) mtDNA was confirmed by direct sequencing as previously described.11 The assembled mitochondrial genomes were evaluated by mapping back the raw reads using CLC Genomics Workbench 9.5. However, a few substitutions, indels, and the occasional GC cluster can be found if our mtDNA is aligned to the mtDNA obtained from the same strains by different groups.13

Rough gene annotation was carried out with MFannot (http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/cgi-bin/mfannot/mfannotInterface.pl).27 Precise exon and intron positions were corrected according to comparison with annotated sequences from several strains of S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus.6,11,20 Intron and endonuclease nomenclature was according to28 and the intergenic open reading frames (ORFs) are numbered according to references.6,29 The sizes of rRNA were inferred from the model elaborated for their equivalents from S. cerevisiae mitochondria.30,31 The 5′ and 3′ ends of rnpB RNA were deduced from the secondary structure consensus.32 Gene nomenclature followed the rules described in GOBASE.33

Saccharomyces arboricolus CBS 10644 mtDNA was assembled from the sequence CM0015799 by manual editing from individual reads (EMBL: ERP001702, ERP001703, ERP001704). Saccharomyces uvarum CBS 395T was assembled from SRR147290 reads downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive, NCBI.26

2.3. Phylogeny

Phylogenetic relationships were analysed by the Maximum likelihood phylogeny PhyML program included in the CLC Genomics Workbench 9.5 package.34 Phylogenetic trees were constructed from unambiguously aligned portions of the concatenated DNA sequences coding for proteins using the neighbor-joining algorithm and the best model (GTR + G + I) selected by model testing tool (hLRT, BIC, AIC, AICc).34 The stability of individual branches was assessed by the bootstrap method.35 DNA concatemers for mitochondrial protein coding sequences belonging to other Saccharomyces strains were extracted from GenBank deposits. The nuclear DNA-derived phylogenetic tree was constructed from protein-coding genes used in population studies.36–39 Because of the hybrid alloploid nature of S. bayanus, S. uvarum and S. pastorianus we used gene sequences from the species that are the least related to S. cerevisiae variants. Corresponding DNA was obtained from assembled contigs occasionally sealed manually from reads (S. cerevisiae NRRL Y-12632T, S. cariocanus CBS 7994T, S. arboricolus NRRL Y-63701, S. paradoxus CBS 2908, S. bayanus CBS 380T). Other concatemers were obtained from sequences, scaffolds (contigs) deposited in the Saccharomyces genome database (http://www.yeastgenome.org/) for S. cerevisiae S288c, S. paradoxus CBS 432,6 for S. pastorianus Weihenstephan 34/70,12 for S. kudriavzevii CBS 8840T and S. mikatae CBS 883940 and for S. arboricolus CBS 10644.9 Data for S. bayanus CBS 380 were obtained from contigs assembled from SRR147291 and for S. uvarum CBS 395T were obtained from contigs assembled from SRR147290.26 Data for S. pastorianus NRRL Y-27171NT (CBS 1538) were compiled from contigs assembled by us and scaffolds BBYX01000001.13 Data for S. eubayanus CBS 12357T were obtained from the final genome assembly and annotations in GenBank JMCK00000000.5 Data accessibility. DNA sequences: GenBank accession nos KY095834–KY095933.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. General features of genes of the genetic code and GUG as a translation start

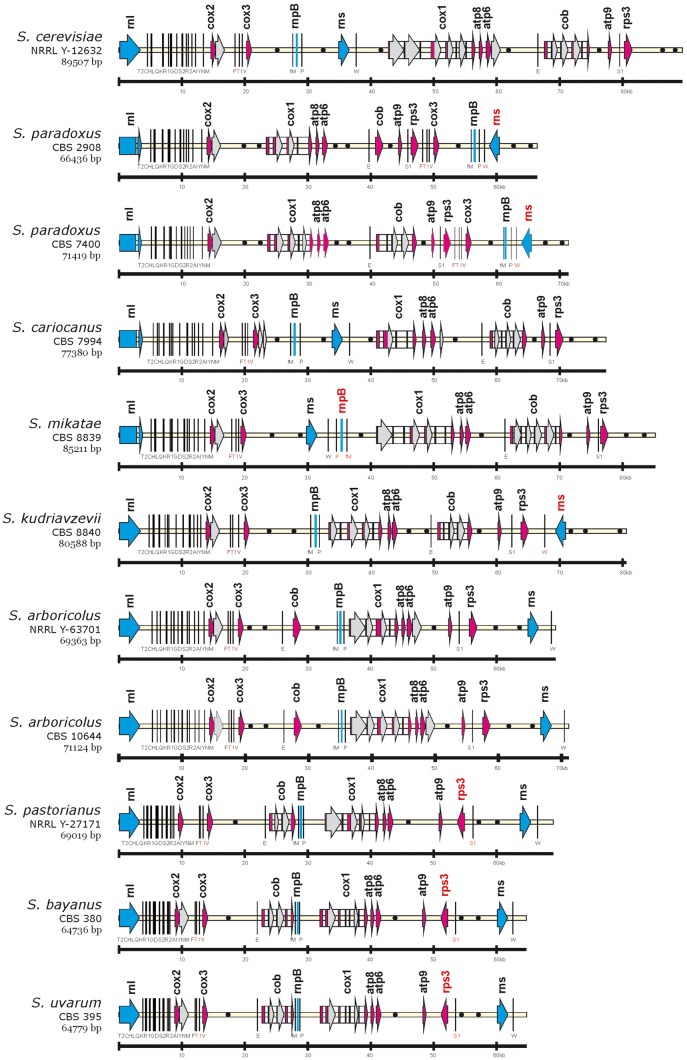

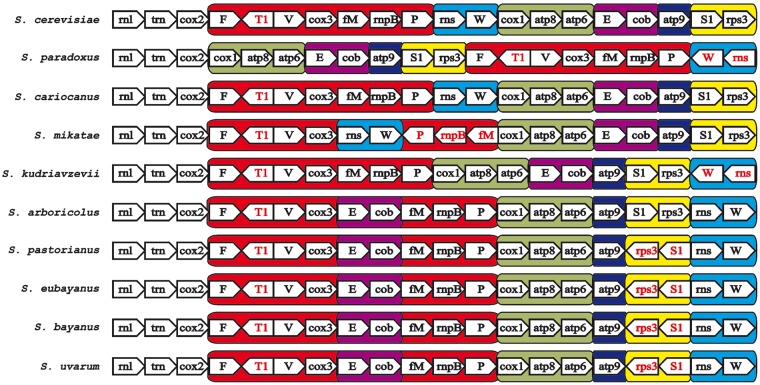

We have successfully completed mitochondrial genomes for nine Saccharomyces species, and their general features are listed in Table 2 (GenBank accession numbers KX657740–KX657750). All mtDNAs are circularly mapped and their size decreases with phylogenetic distance from S. cerevisiae (89.5 kb) to ∼64.7 kb for S. bayanus. GC content varies from 14% for S. paradoxus strains to 19.3% for S. pastorianus and correlates positively with the presence of introns and negatively with the size of AT-rich intergenic spacers. The mtDNAs contain the basic set of genes known in Saccharomyces, coding for the components of cytochrome oxidase (cox1, cox2, cox3), cytochrome b (cob), subunits of ATPase (atp6, atp8, atp9), both rRNA subunits (rnl, rns), the rps3 gene for ribosomal protein, the rnpB gene for the RNA subunit of RNase P and the tRNA package24 (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

General features of mitochondrial genomes

| Species | Strain | Size (bp) | GC (%) | Genes (%) | Spacers (%) | Introns (%) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | NRRL Y-12632NT | 89,507 | 16.8 | 15.6 | 64.1 | 20.3 | KX657745 |

| S. paradoxus | CBS 2908 | 66,436 | 14.0 | 20.3 | 70.7 | 9.0 | KX657748 |

| S. paradoxus | CBS 7400 | 71,419 | 14.5 | 18.9 | 65.6 | 15.6 | KX657749 |

| S. cariocanus | CBS 7994T | 77,380 | 15.6 | 17.8 | 69.8 | 12.5 | KX657744 |

| S. mikatae | CBS 8839T | 85,211 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 62.5 | 21.4 | KX657747 |

| S. kudriavzevii | CBS 8840T | 80,588 | 16.0 | 17.1 | 68.9 | 13.9 | KX657746 |

| S. arboricolus | NRRL Y-63701 | 69,363 | 14.6 | 19.7 | 71.4 | 8.9 | KX657741 |

| S. arboricolusa | CBS 10644T | 71,124 | 14.5 | 19.1 | 69.6 | 11.3 | KX657740a |

| S. pastorianus | NRRL Y-27171NT | 69,019 | 19.3 | 19.9 | 65.9 | 14.2 | KX657750 |

| S. bayanus | CBS 380T | 64,736 | 16.3 | 21.0 | 63.9 | 15.1 | KX657743 |

| S. uvarum | CBS 395T | 64,779 | 16.4 | 21.0 | 63.9 | 15.1 | KX657742 |

aAssembled from individual reads (EMBL: ERP001702, ERP001703, ERP001704).9

Figure 1.

The genetic organization of Saccharomyces mtDNA. For simpler comparison, the circular genomes, exported from Vector NTI, were aligned at the beginning of the large rRNA subunit (rnl). Protein-coding genes, ribosomal RNA, rnpB are marked as arrows and bar, tRNA genes as black lines, introns with white rectangles, intronic and free-standing ORFs by gray arrows and replication origins with black circles. Gene nomenclature follows the rules described in GOBASE (atp for ATP synthetase subunits, cox for cytochrome oxidase subunits, cob for cytochrome b, rns for small rRNA ribosomal subunit, rnl for large rRNA ribosomal subunit, T2, C, H, etc. for particular tRNA coding genes, rps3 for ribosomal protein and rnpB for the RNA subunit of RNase P). Sizes are given on the bottom line in kbp.

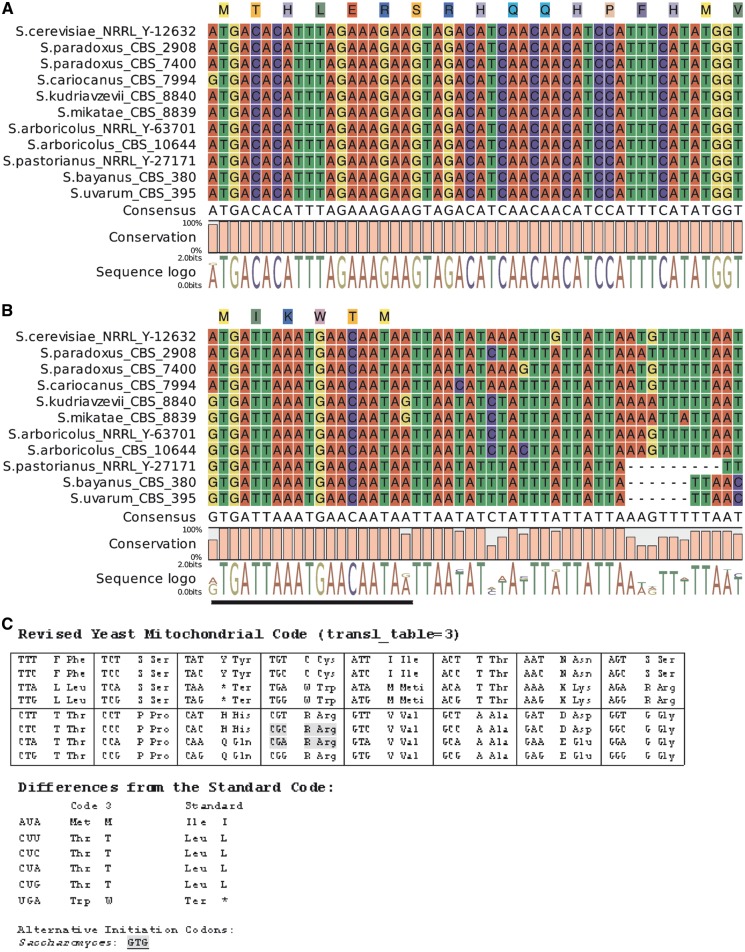

The genetic code in Saccharomyces mtDNA differs from the universal code by TGA being read as tryptophan, CTN as threonine, ATA as methionine and CGN for arginine, with CGA and CGC absent, that is recognized as the ‘yeast mitochondrial code’ (transl_table = 3).41–43 The trnR2 gene (anticodon ACG) was found in all Saccharomyces mtDNAs. Thus, all four CGN codons possess coding potential. However, the CGU codon is present in exons only once (besides S. arboricolus) coding for a non-conserved arginine residue in rps3 protein (Supplementary Material S1). In addition, the CGU codon occurs quite frequently in intron-coded or free-standing ORFs, whereas the CGG codon is present only in GC clusters located inside them. The arginine CGA and CGC codons considered as unassigned are also used sporadically in maturase/homing endonucleases (HE) reading frames coded by introns41–44 (Supplementary Material S1). The most convincing evidence is a CGC codon present in the cox1I2 reading frame in a number of S. cerevisiae strains including type strain NRRL Y-12632 and the well-studied model strain S288c. This reverse transcriptase/maturase protein is required for group II intron splicing from cox1 pre-mRNA as well as for intron mobility.45,46 Apparently, tRNA coded by the trnR2 gene is required in Saccharomyces pre-dominantly for the expression of mobile elements and is therefore gained and lost in different clades from the Saccharomyces/Kluyveromyces complex.47,48 Protein-coding genes start with ATG, with some exceptions. The translation start in the S. cariocanus cox3 gene is GTG (GUG), reported to be nearly as effective as the original ATG in the S. cerevisiae cox2 gene.49 Translation initiation at the nearby downstream AUG is not an option because mutagenesis of the regular initiation codon does not allow translation from this site.49 Instead, a stem loop structure in the mRNA sequence of the first six codons plays a role in the recognition of the translation start.50 The first 50 nucleotides in the cox3 genes of all sequenced Saccharomyces are identical, which emphasizes the reliability of GUG as the initiation start codon (Fig. 2A, B). Atypical start codons are present in many mitochondrial systems, but GUG as a start codon is known only in some birds, invertebrates, plants and protists, but not in yeast and molds.43,44 Also, a maternally inherited and practically homoplasmic mtDNA mutation, 8527 A > G, changing the initiation codon AUG into GUG, was observed in the human atp6 gene. The patient harbouring this mutation exhibited clinical symptoms of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, but his mother was healthy.51 The second exception is free-standing ORF1s in S. kudriavzevii, S. mikatae, S. bayanus, S. uvarum, S. arboricolus and S. pastorianus, where GUG is used as a translation start site. This gene with unknown function codes for a hypothetical maturase-like protein, the start codon overlaps with the 3′ end of the cox2 gene and the reading frame extends 16 bp downstream of the cox2 stop codon. Consequently, the ‘yeast mitochondrial code’ should be updated to accept CGA and CGC as arginine codons and GTG as the alternative initiation codon (Fig. 2C). The preferable termination codon in exons is UAA, and UAG is used only occasionally in cox2 of S. kudriavzevii and S. mikatae and more often in intron-coded ORFs. Codon usage in the reading frames shows a strong bias towards codons ending with T or A (in 10:1), as previously observed in the mitochondrial genomes of other yeasts6,11 (Supplementary Material S1).

Figure 2.

GTG as the initiation codon and revised yeast mitochondrial code. (A) Initiation codons in cox3 gene. (B) Initiation codons in ORF1 gene. Sequences overlapping with cox2 3′end are underlined. (C) Revised yeast mitochondrial code. Exceptional codons are grey-shadowed.

All sequenced mitochondrial genomes exhibit sequence conservation at the nucleotide level within exons (excluding extremely variable rps3), with at least 94% sequence identity between the most unrelated species and a substitution rate of 11%. The substitutions are mostly neutral and have a low impact on the protein sequence, as they generate nearly identical amino acid residues. Therefore, the overall protein identity, even among less-related species, is 97%. Interestingly, the atp9 protein sequence is identical in all sequenced species. The same DNA substitution rate (6%) in the other small gene, atp8, is responsible for the three changes at the protein level (Supplementary Material S2).

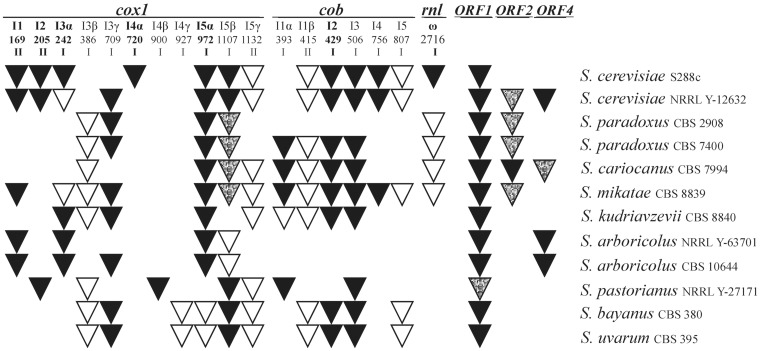

3.2. Introns and free-standing ORFs

Introns are present in Saccharomyces only within cox1, cob and rnl genes.22,27 Although the majority are group I introns, four of them belong to group II, and only two of these (cox1I1, cox1I2) code for a protein with the maturase/reverse transcriptase motif. The intervening sequences are inserted into the same sites as has been described in other Saccharomyces, especially more than 100 strains of S. cerevisiae11,19,20,21,52 (Fig. 3). However, a detailed analysis indicates that the insertion site for cox1I3α should be shifted to position 242. Position 243 would generate lysine instead of an asparagine residue in the GGFGN section in both S. arboricolus molecules. This motif is conserved across the tree of life from yeast to humans. G-G-F-G-N-[WY]-[FL]-[MV] is a part of the well-recognized water membrane interface motif in cytochrome c and quinol oxidases (MeMotif—http://projects.biotec.tu-dresden.de/memotif).53

Figure 3.

Occurrence of introns and free-standing ORFs. Introns and free-standing ORFs with at least one motif characteristic for the homing endonucleases (LAGLIDADG, GIY-YIG, etc.) are in black; without reading frame are white; with truncated ORF interrupted by stop codon are spotted. Numbers indicate the base preceding the intron insertion site in the CDS. Positions of introns, known as mobile, in S. cerevisiae are marked in bold6; I—group I introns, II—group II introns. ORF1, ORF2 and ORF4 correspond to the nomenclature used in reference29 (their ORF5 is an ORF coded by the rnl ω intron). Only ORFs containing at least one endonuclease/maturase motif were considered.

A number of introns also contain ORFs in phase with the upstream exon, sometimes interrupted by a frame-shift stop codon, often due to the insertion of GC clusters. Only those possessing at least one motif characteristic for the HE (LAGLIDADG, GIY-YIG, etc.) were considered as potentially active54,55 (Fig. 3).

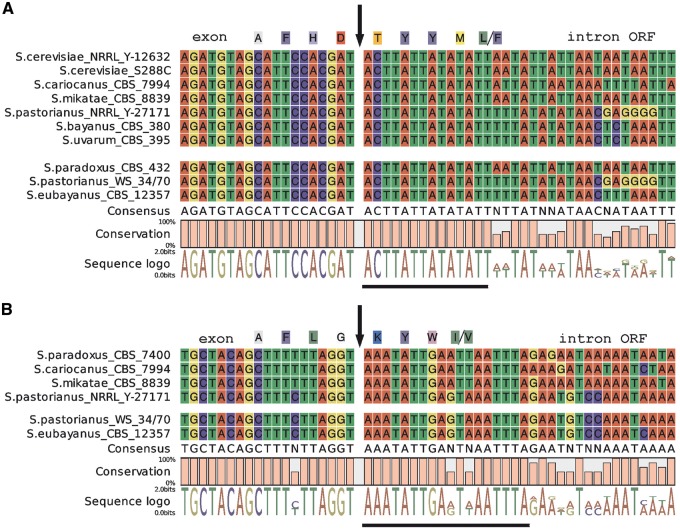

However, there are two exceptions: cox1I5β and cobI1α, where an ORF coding for a nuclease/maturase motif is not fused to the upstream exon. cox1I5β is not known as mobile and the splicing requires at least five different nuclei-coded factors and an ORF from cobI3.6,56 The reason is that the 3′ splice site lies unusually far from the catalytic core of the intron; therefore, the ORF 357 amino acids (AA) long containing two LAGLIDADG motifs in the S288c strain was not considered as potentially active.56 But a recent S. cerevisiae mitochondrial transcriptome study revealed an alternative splice site that puts the cox1I5β ORF in frame with the upstream exon.57 We found the same ACTTATTATATATT consensus of the alternative splice site in several other Saccharomyces species (S. mikatae, S. cariocanus, S. bayanus, S. uvarum, S. pastorianus strains and S. eubayanus and S. paradoxus CBS 432; Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Alternative splicing of cox1I5β (A) and cobI1α (B). Arrows mark exons–introns boundaries. Consensus of alternative splice site as described in reference57 and hypothetical alternative splice site in cobI1α are underlined.

Perhaps, a similar mechanism can be used in cobI1α. We found a hypothetical alternative splice site sharing sequence similarity AAATATTAG(G/A)T(A/T)AATTTA allowing the translation of an intron reading frame with an upstream exon (Fig. 4B). In S. cariocanus, S. pastorianus, S. mikatae and S. eubayanus it contains a 169–297 AA-long reading frame with one GIY-YIG endonuclease maturase motif.58

Introns, especially those containing HEs, represent a class of mobile elements spread horizontally into an intron-less allele by ‘homing’. They can be found in different species in the same position of the same gene in a chain-involved cyclical gain and loss.19,59,60 Consequently, they are randomly distributed among the different species.19,20 However, there are a few remarkable exceptions. Intron cox1I3β has not been found in S. cerevisiae although more than a hundred strains have been sequenced. Besides both S. arboricolus strains, cox1I3β is present in all other Saccharomyces species.19–21 Other evidence of uneven cox1I3β distribution comes from S. cerevisiae xenomitochondrial cybrids containing S. paradoxus mtDNA. They exhibit a slower growth rate on a non-fermentable carbon source, decreased respiration capacity and reduced cytochrome aa3 content associated with the inefficient splicing of cox1I3β.22 Apparently, the occurrence of cox1I3β is related to Dobzhansky–Muller nuclear incompatibilities in nucleo-mitochondrial communication that may result in the divergence of yeast species.22

Very rare is the orphan cox1I4γ intron that occurs only in S. bayanus CBS 380 and S. uvarum CBS 395. We were unable to find homologs in spite of extensive search in the literature and databases.19 Also, cox1I4α, well known as coding for HE I-Scell with a LAGLIDADG motif,61 was not identified in any other Saccharomyces but S. cerevisiae. Unlike cox1I4γ it can be found in less related species from the Saccharomyces/Kluyveromyces complex Naumovia castellii62 and Kluyveromyces marxianus species.19,63

Intron homing is catalyzed by HEs64,65 that have different evolutionary history and can exist alone.66,67 Such free-standing ‘endonucleases’, named ORFs,29 have already been described in S. cerevisiae and S. pastorianus mtDNA, but their occurrence is strain dependent.6,29ORF1 orthologs are most frequent in different Saccharomyces species (Fig. 3). They code for one or two LAGLIDADG motifs and a DNA-binding helix-turn-helix domain.68 Because of the number of stop codons or a GC cluster insertion ORF2 is present mostly in truncated form.19,21 A reading frame coding for one LAGLIDADG motif was found only in S. cariocanus. We were unable to detect ORF3 in any ‘non-cerevisiae’ Saccharomyces. Apparently this dubious ORF does not encode a functional protein. Full size ORF4 can be found in S. cerevisiae and S. arboricolus. Among all previously identified small ORFs, regions with significant homology to ORF56 were found only in S. paradoxus11 and S. cariocanus. Therefore, ORF5 is considered as a probable genomic artifact,69 although very small proteins coded by mtDNA are expected, since at least two small proteins were reported to be coded by rns in mammalian mitochondria.70,71

3.3. Intergenic DNA, GC clusters and origins of replication

The putative origins of replication in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus are ∼270 bp in length and contain GC blocks separated by AT-rich stretches.6,72 According to novel bioinformatics analysis (strain S288c) it is a five-part consensus sequence [GGGGGAGGGGGTGGGTGAT ∼200 A/T-rich GGGTCCC 29 A/T-rich GGGACC] downstream of the 20-base promoter [DDWDWTAWAAGT↓ARTADDDD].57Saccharomyces cerevisiae mtDNA contains seven or eight ori elements, depending on the strain, but only ori 2, 3 and 5 are active. They contain a transcription initiation site adjacent to the five-part consensus sequence providing a contiguous transcript of >350 nucleotides. The other ori sites are disabled by the insertion of a G-class GC cluster CCCGGTTTCTTACGAAACCGGGACCTCGGAGA(C/A)GT into the promoter site.57,73 The ori elements are present in all Saccharomyces species. Their number decreases with the phylogenetic distance from S. cerevisiae as the S. paradoxus species possesses eight, but species from the lager beer species/S. uvarum clade only four (Table 3). All of them can be potentially active as they are adjacent to the hypothetical promoter sequence DDWDWTAWAAGT↓ARTADDDD57 (Supplementary Material S4A).

Table 3.

Replication origins and GC clusters

| Saccharomyces strain | ori | Number of GC clusters |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | V | M1 | M1′ | M2 | M2′ | M2″ | M3 | M4 | U | SpS* | Classified/total | ||

| S. cerevisiae | 7/2a | 5 | 4 | 48 | 7 | 46 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 50 | – | 127/177 |

| NRRL Y-12632T | |||||||||||||

| S. paradoxus | 8/8 | – | 8 | 20 | 1 | 12 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | – | 46/76 |

| CBS 2908 | |||||||||||||

| S. paradoxus | 8/8 | – | 9 | 19 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 32 | – | 45/77 |

| CBS 7400 | |||||||||||||

| S. cariocanus | 7/7 | – | 37 | 10 | 2 | 23 | 5 | – | – | – | 72 | – | 77/149 |

| CBS 7994T | |||||||||||||

| S. mikatae | 7/7 | – | 13 | 32 | 7 | 30 | 1 | – | – | 10 | 50 | – | 90/143 |

| CBS 8839T | |||||||||||||

| S. kudriavzevii | 8/8 | – | 8 | 26 | 9 | 37 | 5 | – | – | – | 51 | – | 85/136 |

| CBS 8840T | |||||||||||||

| S. arboricolus | 6/6 | – | 1 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 2 | – | – | 76 | 7 | 36/112 |

| NRRL Y-63701 | |||||||||||||

| S. arboricolus | 6/6 | – | 1 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 6 | – | 2 | 63 | 6 | 38/105 |

| CBS 10644T | |||||||||||||

| S. pastorianus | 4/4 | 5 | 3 | 13 | – | 44 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 101 | 6 | 82/183 |

| NRRL Y-27171T | |||||||||||||

| S. bayanus | 4/4 | 5 | 13 | 16 | – | 17 | – | – | – | – | 38 | 7 | 57/95 |

| CBS 380T | |||||||||||||

| S. uvarum | 4/4 | 5 | 13 | 17 | – | 17 | – | – | – | – | 38 | 7 | 58/96 |

| CBS 395T | |||||||||||||

| S. cerevisiae | 8/3 | 5 | 4 | 55 | 7 | 37 | 9 | 13 | 3 | 9 | 48 | – | 127/177 |

| S288c | |||||||||||||

| S. eubayanus | 4/4 | 1 | – | 26 | – | 33 | – | – | – | – | 56 | 5 | 64/120 |

| CBS 12357T | |||||||||||||

| S. pastorianus | 4/4 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 50 | 3 | 10 | – | – | 85 | 9 | 86/171 |

| WS 34/70 | |||||||||||||

| S. paradoxus | 8/8 | – | 7 | 14 | – | 8 | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 50 | – | 32/82 |

| CBS 432T | |||||||||||||

aori2 considered as active is absent; G, V, M1, M1′, M2, M2′, M2″, M3 and M4 are GC cluster classes identified according to consensus described in detail in reference20 with various degrees of degeneration (Supplementary Material S3C); U—unclassified GC clusters defined as longer than ≥ 20 nt with GC content ≥ 40%; SpS—species-specific GC clusters found in the S. bayanus, S. uvarum, S. pastorianus clade consensus sequence TCGTNWCGYACCGTCCAATWGGACGGTACG and in S. arboricolus GGGGTCCC N(28–30) GGGGTCCC. Strains assembled in this work are marked in bold.

GC clusters were originally defined as regions 35 bp long on average and 45–62% GC74 and are in general the major source of noticeable intergenic region polymorphism.6 According to the characteristic primary structures, they have been assigned to seven families which exhibit varying degrees of homology.73,74 Recently, the M2″ class consensus was reduced to 14 bases (TCCGGCCGAAGGAG).20 Therefore, we took into consideration as GC clusters only regions longer than ≥ 20 nt with GC content ≥ 40%. The average number of GC clusters in S. cerevisiae is above 100 and their occurrence decreases in other Saccharomyces species20 from 90 to 30 (Table 3). A G-class ori-specific GC cluster has been found in any species from the S. bayanus, S. uvarum, S. pastorianus clade, but remote from ori. The most frequent are M1 and M2 classes, although members of other classes can be found. In addition, a species-specific GC-rich sequence (GGGGTCCC N(28–30) GGGGTCCC) was recognized in both S. arboricolus strains and a GC cluster with the consensus TCGTNWCGYACCGTCCAATWGGACGGTACG in species from the lager beer species/S. uvarum clade.

3.4. Transcription units and adjacent motifs

The highly-conserved sequence motif WTATAAGTA is known as the yeast mitochondrial transcription initiation site.6,75–77 Recently, transcriptome analysis confirmed experimentally the sequence DDWDWTAWAAGT↓ARTADDDD as the consensus promoter site in S. cerevisiae57 and 19 potential transcription initiation sites6 were reduced to 11. We found these consensus promoter sites in all sequenced Saccharomyces at approximately the same position as they were reported for S. cerevisiae. Because of the rearrangement of the trnS1-rps3 block in the mtDNA of the S. bayanus, S. uvarum, S. pastorianus clade, an additional transcription site was found upstream of the trnS1 gene (Supplementary Material S4A). When all hypothetical promoter sites are compared, the S. cerevisiae consensus57 is slightly degenerated mainly at the 5′ site to DNNDNTAWAAGT↓ARTADDDD that is more related to the original nonanucleotide WTATAAGTA in spite of the phage T7 origin of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Apparently, the 23 base-long phage T7 consensus promoter is reduced in Saccharomyces mtDNA.

The 3′ termini of mitochondrial mRNA cleavage sites in budding yeast are recognized according to the postulated dodecamer motif 5′-AAUAA (U/C) AUUCUU-3′ in the 3′ UTR region.77–79 A processing site was confirmed by transcriptome analysis where an alternative heptakaidecamer 5′AATAATATTCTTAT↓AGTCCGGCC↓CGCCC with part of the M2 GC cluster is recognized instead.57 Variations to the dodecamer have been found in all protein-coding transcription units at the 3′ UTR region of all Saccharomyces species, in most cases up to 200 nucleotides downstream from the termination codon (Supplementary Material S4B). A putative atp8 transcription termination site exhibits the most degenerated consensus sequence. Interesting features are the multiple cleavage sites for ORF1 present in S. mikatae, S. kudriavzevii and S. arboricolus. An alternative heptakaidecamer transcription processing site was found only in S. cerevisiae.

3.5. Gene order and synteny

The most profound feature is the alteration in gene order that involves mainly trnfM-rnpB-trnP, rns-trnW, trnE-cob and trnS1-rps3 gene clusters. S. cerevisiae NRRL Y-12632 mtDNA with a length of almost 90 kb belongs among the largest genomes and has the same gene order as is known in 105 other strains.20,21S. paradoxus CBS 2908 and CBS 7400 mtDNA differs in size (66 kb versus 71 kb), associated with the intron occurrence in the cob gene. The gene order is the same as in 14 other strains.11,19 They differ from S. cerevisiae by the excision of the trnFT1V-cox3-trnfM-rnpB-trnP-rns-trnW segment that is translocated behind the trnS1-rps3 gene cluster where rns-trnW is inverted (Figs 1 and 5). Surprisingly, the 77 kb mtDNA of S. cariocanus is syntenic to S. cerevisiae, although these species can be distinguished according to the cox1I3β intron present in S. cariocanus (Figs 1 and 3). S. mikatae mtDNA is >85 kb long and the gene architecture is altered from S. cerevisiae by the movement and inversion of the trnfM-rnpB-trnP gene cluster behind the rns-trnW locus (Fig. 5). S. kudriavzevii mtDNA is ∼80 kb long and the gene order differs from S. cerevisiae by the excision of rns-trnW and its transplacement to the complementary strand at the 3′ end of the trnS1-rps3 gene cluster (Fig. 5). Both S. arboricolus mtDNAs are around 70 kb in size and the genome architecture exhibits very extensive reshuffling in relation to S. cerevisiae. The rns-trnW cluster is excised and transferred at the 3′ end of the atp9-trnS1-rps3 gene cluster. The remaining trnfM-rnpB-trnP-cox1-atp8-atp6 genome segment is translocated at the end of the cob gene (Figs 1 and 5). S. bayanus, S. eubayanus, S. uvarum and S. pastorianus share the same mtDNA architecture. Besides all alterations known for S. arboricolus the characteristic transcription unit atp9-trnS1-rps3 is broken and the trnS1-rps3 part is inverted at the same location (Figs 1 and 5). Strains from the lager beer species/S. uvarum clade despite their hybrid nature are classified as separate species, although they exhibit strikingly similar mtDNA sequences. Nearly identical are mtDNAs from S. uvarum CBS 395T and S. bayanus CBS 380T.

Figure 5.

Comparison of mitochondrial gene order in Saccharomyces. Individual gene clusters are highlighted by different shades of grey. Pentagon symbols indicate the transcription direction.

The alteration in gene order within yeast genera is not so frequent and is associated with the genome size. The majority of yeast mtDNA is relatively small (< 40 kbp) with the genes located on the same strand. The size of <15% of mtDNA exceeds 50 kb and the genes are scattered in conserved blocks (e.g. cox1-atp8-atp6, rnl-trn) coded in both strands with altered transcription orientation.7 Obviously, larger genomes like in Saccharomyces are more prone to rearrangements. An extremely high degree of gene conservation and synteny is the characteristic feature among and within the species possessing smaller mtDNA of the Lachancea,80Torulaspora81 and Yarrowia clades.82 However, significant mitochondrial genome rearrangement was observed in yeasts with larger mtDNA from the Nakaseomyces83 and Dekkera/Brettanomyces genera.84 Apparently, alteration in mtDNA gene order depends most of all on the size of intergenic regions and is obvious if their ratio to genes exceeds 60%.7 The gene order alteration mechanism was deduced exclusively from the DNA sequence, proposing an intermediate with duplicate segments, associated with conserved gene blocks mimicking transcription units.11,84,85 This is not the case in S. bayanus, S. eubayanus, S. uvarum and S. pastorianus where the atp9-trnS1-rps3 transcription unit is broken apart and the transposition of trnS1-rps3 to the opposite strand requires formation of a de novo promoter.

3.6. Phylogeny and taxonomy

As mentioned above, currently S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. mikatae, S. kudriavzevii, S. arboricolus, S. bayanus, S. uvarum and S. pastorianus are the only species accepted by taxonomists as Saccharomyces.1 However, whole (nuclear) genome studies demonstrated that S. pastorianus is an alloploid of S. cerevisiae and the newly described species S. eubayanus as well as S. bayanus is a hybrid between S. uvarum and S. eubayanus with a small contribution of S. cerevisiae.4,5,13,26,86Saccharomyces cariocanus is reproductively isolated by four chromosomal translocations from S. paradoxus but not by sequence and therefore is considered to be a S. paradoxus subspecies.4,5,86 All these data came exclusively from nuclear genetic information, although mitochondrial genomes are more susceptible to mutations than their nuclear counterparts.

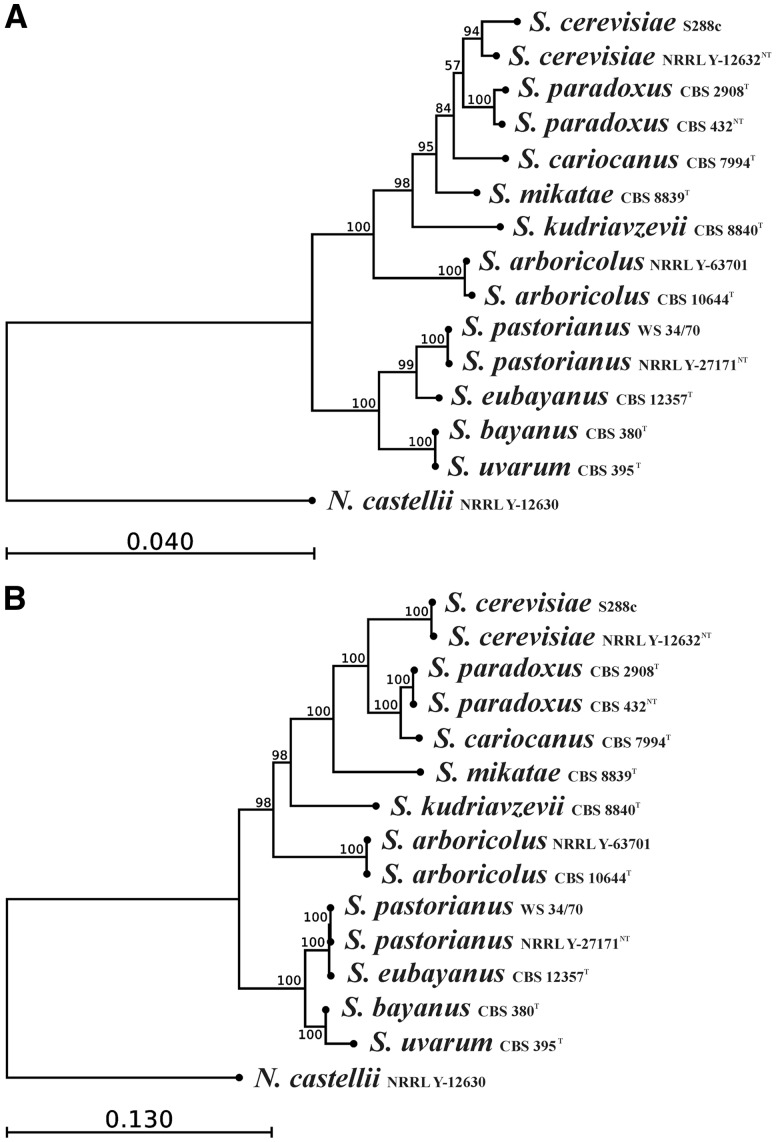

The accuracy of taxonomic classification as well as the evolution history can be inferred from phylogenetic trees derived from concatenated DNA or protein sequences of mitochondrial or nuclear origin. However, support for many lineages in present phylogenetic trees is often weak and more robust analyses of relationships will require whole genome comparisons.87 To shed light on these taxonomy–phylogeny pitfalls we constructed phylogenetic trees from unambiguously aligned portions of the concatenated mtDNA sequences coding for proteins (Fig. 6A). Because of limited gene availability, we used 10 nuclear genes as a good compromise, especially if they had been used in population studies36–39 (Fig. 6B). Branching in both trees does not correlate with basic taxonomic classification and the tree derived from the combined sequences of the D1/D2 LSU RNA gene and ITS used in taxonomy1 (Fig. 6). Phylogenetic comparison of mitochondrial and nuclear genes clearly demonstrates that S. cariocanus should be assigned as a separate species. It belongs in the nuclei-derived tree to the S. paradoxus clade; however, in the mitochondrial tree it forms a statistically significant separate branch. Considering its mtDNA gene order, which differs from that of S. paradoxus, and the presence of the cox1I3β intron, S. cariocanus should be designated as a separate species (Fig. 6). This conclusion, rather than horizontal transfer, supports the low spore viability obtained from crosses with the S. paradoxus tester as well as the absence of any S. cerevisiae genes in the nuclear genome.4,5,86 Multilocus phylogenies based on conserved mitochondrial genes (except extremely variable rps3) are largely representative; however, they occasionally do not correlate with trees derived from nuclear genes.7,84 The most plausible explanation for this discrepancy is different selection pressures for mitochondrial and nuclear genes, where complex patterns of hybridization and introgression are involved.7,84 However, the S. cariocanus paradox can be also explained as a partially developing divergence, because the genus Saccharomyces is considered as a continuum of taxa differentiating towards speciation.1

Figure 6.

Saccharomyces phylogeny. Both trees were constructed from unambiguously aligned concatenated DNA sequences using the Maximum likelihood phylogeny PhyML program. (A) mtDNA-derived phylogeny from DNA sequences coding for proteins in the order cox1, atp8, atp6, cob, atp9, cox2, cox3. (B) Nuclear DNA-derived phylogenetic tree from CCA1, CYT1, MLS1, RPS5, LAS1, MET4, NUP116, ZDS2, PDR10 and DSN1 protein-coding genes used in population studies.36–39 The branch length is proportional to the nucleotide differences indicated by the bar. The numbers given at the nodes are the frequencies of a given branch appearing in 1,000 bootstrap replications. All are above 50%, indicating good statistical support. Naumovia castellii NRRL Y-12630 was used as an outgroup.

Even more complicated relationships are found among the hybrid species from the lager beer species/S. uvarum clade (Fig. 6). It consists historically of two species associated with human activities. S. pastorianus is a typical bottom lager beer yeast and S. bayanus (CBS 380) was isolated from turbid beer. Only S. uvarum (CBS 395) was isolated from natural substrate (blackcurrant).26 The origin of S. pastorianus was studied in detail and has been elucidated by the discovery of a new species S. eubayanus.5 All modern S. pastorianus are aneuploid descendants of a tetraploid S. eubayanus/S. cerevisiae hybrid (2n, 2n) with limited loss of contribution from either parent.4,5,13,88 Apparently, the S. pastorianus strain sequenced in this work as well as a number of other strains inherited mtDNA exclusively from S. eubayanus mtDNA.13,89 The systematics of S. bayanus and S. uvarum has been confusing and controversial for decades. S. uvarum (S. bayanus var. uvarum) strains represent a nearly pure lineage that contains very little genetic input from other Saccharomyces species although type strain CBS 395 does not produce viable spores and sequencing revealed that the strain is aneuploid.26 However, a number of different strains (including CBS 7001 ‘genomic type strain’) are good sporulants and introgression from other Saccharomyces species is low.4,90S. bayanus is not a ‘species’ in an evolutionary sense and should be rather understood as a product of the artificial brewing environment with no occurrence in nature. Therefore, all known strains of S. bayanus (including the type strain CBS 380) are hybrids of S. eubayanus and S. uvarum that contain contributions from S. cerevisiae in at least some cases.26 Comparison of mtDNA clearly demonstrates its S. uvarum origin in S. bayanus CBS 380. A similar conclusion was reported by91 when they compared part of the cox2 gene in the collection of S. eubayanus and its interspecies hybrids. A model of S. bayanus formation involves multiple hybridization events of S. pastorianus with wild strains of S. uvarum. In the case of S. bayanus CBS 380 it happened only recently as mtDNA from S. uvarum CBS 395T and S. bayanus CBS 380T is nearly identical. They only differ in four substitutions and five indels of which one is the insertion of a GC cluster and one a TTATTTAC repeat. Therefore, comparison of mtDNA should not be neglected in genomic studies as it is an important tool to understand the origin and evolutionary history of some yeast species.

4. Conclusions

We sequenced mtDNA from a variety of Saccharomyces species by Illumina MiSeq. All are circularly mapped molecules decreasing in size with phylogenetic distance from S. cerevisiae but with similar gene content including regulatory and selfish elements like origins of replication, introns, free-standing ORFs or GC clusters. Their most profound feature is species-specific alteration in gene order, apparently accompanying the speciation process in yeasts with larger mtDNA. Conserved mtDNA gene order seems to be a species-specific feature as pointed out by the comparison of more than 100 S. cerevisiae strains20,21 and ∼15 S. paradoxus strains19 as well as 50 strains from Lachancea thermotolerans.80 On the other hand, reshuffling of mitochondrial genes evidently accompanies the yeast speciation process if mitochondrial genomes are large enough.7 The genetic code differs from well-known yeast mitochondrial code as GUG is used as the translation start in the S. cariocanus cox3 gene as well as in some free-standing ORF1. Arginine CGA and CGC codons considered as unassigned are present in maturases/HE coded by introns. Because of the alternative splicing of cox1I5β and cobI1α, AUA considered as an initiation codon is absent. The multilocus phylogeny, inferred from mtDNA, does not correlate with the trees derived from nuclear genes. mtDNA data demonstrate that S. cariocanus should be assigned as a separate species and S. bayanus CBS 380 should not be considered as a distinct species due to mtDNA nearly identical to S. uvarum mtDNA. Apparently, comparison of mtDNAs should be included in genomic studies, as it is an important tool to understand the origin and evolutionary history of some yeast species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. The study is a result of implementation of project REVOGENE – Research Center for Molecular Genetics (ITMS 26240220067) supported by the Research & Development Operational Program funded by the ERDF. Part of this work was funded by grants from VEGA 1/0360/12 and 1/0048/16.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Accession numbers

KX657740, KX657741, KX657742, KX657743, KX657744, KX657745, KX657746, KX657747, KX657748, KX657749, KX657750

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at DNARES online.

References

- 1. Vaughan-Martini A., Martini A.. 2011, Saccharomyces meyen ex reess (1870) In: Kurtzman C.P., ed. The Yeasts, A Taxonomic Study, Elsevier: Amsterdam, NL: pp. 733–46. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Replansky T., Koufopanou V., Greig D., Bell G.. 2008, Saccharomyces sensu stricto as a model system for evolution and ecology, Trends Ecol. Evol., 23, 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sipiczki M. 2008, Interspecies hybridization and recombination in Saccharomyces wine yeasts, FEMS Yeast Res., 8, 996–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borneman A.R., Pretorius I.S.. 2015, Genomic insights into the Saccharomyces sensu stricto complex, Genetics, 199, 281–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baker E., Wang B., Bellora N., et al. 2015, The genome sequence of Saccharomyces eubayanus and the domestication of lager-brewing yeasts, Mol. Biol. Evol., 32, 2818–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foury F., Roganti T., Lecrenier N., Purnelle B.. 1998, The complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, FEBS Lett., 440, 325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Freel K.C., Friedrich A., Schacherer J.. 2015, Mitochondrial genome evolution in yeasts: an all-encompassing view, FEMS Yeast Res., 15, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kellis M., Patterson N., Endrizzi M., Birren B., Lander E.S.. 2003, Sequencing and comparison of yeast species to identify genes and regulatory elements, Nature, 423, 241–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liti G., Ba A.N.N., Blythe M., et al. 2013, High quality de novo sequencing and assembly of the Saccharomyces arboricolus genome, BMC Genomics, 14, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hittinger C.T., Rokas A., Bai F-Y., et al. 2015, Genomics and the making of yeast biodiversity, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 35, 100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Procházka E., Franko F., Poláková S., Sulo P.. 2012, A complete sequence of Saccharomyces paradoxus mitochondrial genome that restores the respiration in S. cerevisiae, FEMS Yeast Res., 12, 819–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakao Y., Kanamori T., Itoh T., et al. 2009, Genome sequence of the lager brewing yeast, an interspecies hybrid, DNA Res., 16, 115–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Okuno M., Kajitani R., Ryusui R., Morimoto H., Kodama Y., Itoh T.. 2016, Next-generation sequencing analysis of lager brewing yeast strains reveals the evolutionary history of interspecies hybridization, DNA Res., 23, 67–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu L., Li Y., Li S., et al. 2012, Comparison of next generation sequencing systems, J. Biomed. Biotechnol., 2012, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quail M.A., Smith M., Coupland P., et al. 2012, A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers, BMC Genomics, 13, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skelly D.A., Merrihew G.E., Riffle M., et al. 2013, Integrative phenomics reveals insight into the structure of phenotypic diversity in budding yeast, Genome Res., 23, 1496–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bergstrom A., Simpson J.T., Salinas F., et al. 2014, A high-definition view of functional genetic variation from natural yeast genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol., 31, 872–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lang B.F., Jakubkova M., Hegedusova E., et al. 2014, Massive programmed translational jumping in mitochondria, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 111, 5926–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu B., Hao W.. 2015, A dynamic mobile DNA family in the yeast mitochondrial genome, G3 (Bethesda), 5, 1273–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolters J.F., Chiu K., Fiumera H.L.. 2015, Population structure of mitochondrial genomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, BMC Genomics, 16, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strope P.K., Skelly D.A., Kozmin S.G., et al. 2015, The 100-genomes strains, an S. cerevisiae resource that illuminates its natural phenotypic and genotypic variation and emergence as an opportunistic pathogen, Genome Res., 25, 762–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Špírek M., Poláková S., Jatzová K., Sulo P.. 2015, Post-zygotic sterility and cytonuclear compatibility limits in S. cerevisiae xenomitochondrial cybrids, Front. Genet., 5, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Defontaine A., Lecocq F.M., Hallet J.N.. 1991, A rapid miniprep method for the preparation of yeast mitochondrial DNA, Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Piškur J. 1989, Respiratory-competent yeast mitochondrial DNAs generated by deleting intergenic region, Gene, 81, 165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piškur J., Smole S., Groth C., Petersen R.F., Pedersen M.B.. 1998, Structure and genetic stability of mitochondrial genomes vary among yeasts of the genus Saccharomyces, Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol., 48, 1015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Libkind D., Hittinger C.T., Valério E., et al. 2011, Microbe domestication and the identification of the wild genetic stock of lager-brewing yeast, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 108, 14539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lang B.F., Laforest M.-J., Burger G.. 2007, Mitochondrial introns: a critical view, Trends Genet., 23, 119–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lambowitz A.M., Belfort M.. 1993, Introns as mobile genetic elements, Annu. Rev. Biochem., 62, 587–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Zamaroczy M., Bernardi G.. 1986b, The primary structure of the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae – a review, Gene, 47, 155–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Konings D.A.M., Gutell R.R.. 1995, A comparison of thermodynamic foldings with comparatively derived structures of 16S and 16S-like rRNAs, RNA, 1, 559–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fields D.S., Gutell R.R.. 1996, An analysis of large rRNA sequences folded by a thermodynamic method, Fold. Des., 1, 419–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seif E.R., Forget L., Martin N.C., Lang B.F.. 2003, Mitochondrial RNase P RNAs in ascomycete fungi: lineage-specific variations in RNA secondary structure, RNA, 9, 1073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Brien E.A., Zhang Y., Yang L.S., Wang E., Marie V., Lang B.F., Burger G.. 2006, GOBASE – a database of organelle and bacterial genome information, Nucleic Acids Res., 34, D697–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CLC Genomics Workbench 9.5.2. https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/

- 35. Felsenstein J. 1988, Phylogenies from molecular sequences: inference and reliability, Annu, Rev. Genet., 22, 521–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fay J.C., Benavides J.A.. 2005, Evidence for domesticated and wild populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PLoS Genet., 1, 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aa E., Townsend J.P., Adams R.I., Nielsen K.M., Taylor J.W.. 2006, Population structure and gene evolution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, FEMS Yeast Res., 6, 702–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayoub M.J., Legras J.L., Saliba R., Gaillardin C.. 2006, Application of multi locus sequence typing to the analysis of the biodiversity of indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine yeasts from Lebanon, J. Appl. Microbiol., 100, 699–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Q.M., Liu W.Q., Liti G., Wang S.A., Bai F.Y.. 2012, Surprisingly diverged populations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in natural environments remote from human activity, Mol. Ecol., 21, 5404–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scannell D.R., Zill O.A., Rokas, et al. 2011, The awesome power of yeast evolutionary genetics: new genome sequences and strain resources for the Saccharomyces sensu stricto genus, G3 (Bethesda), 1, 11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Clark-Walker G.D., Weiller G.F.. 1994, The structure of the small mitochondrial DNA of Kluyveromyces thermotolerans is likely to reflect the ancestral gene order in fungi, J. Mol. Evol., 38, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lang B.F., Lavrov D., Beck N., Steinberg S.V.. 2012, Mitochondrial tRNA structure, identity, and evolution of the genetic code, In: Bullerwell C. E., ed., Organelle Genetics. Evolution of Organelle Genomes and Gene Expression, Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, pp. 431–74. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Elzanowski A., Ostell J.. 2013, The genetic codes, NCBI website, 2010, Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Utils/wprintgc.cgi.

- 44. García-Guerrero A.E., Zamudio-Ochoa A., Camacho-Villasana Y., García-Villegas R., Reyes-Prieto A., Pérez-Martínez X.. 2016, Evolution of translation in mitochondria, In: Hernández G., Jagus R., eds., Evolution of the Protein Synthesis Machinery and its Regulation, Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, pp. 109–43. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moran J.V., Zimmerly S., Eskes R., et al. 1995, Mobile group II introns of yeast mitochondrial DNA are novel site-specific retroelements, Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 2828–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lambowitz A.M., Zimmerly S.. 2004, Mobile group II introns, Ann. Rev. Genet., 38, 1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kurtzman C.P. 2003, Phylogenetic circumscription of Saccharomyces, Kluyveromyces and other members of the Saccharomycetaceae, and the proposal of the new genera Lachancea, Nakaseomyces, Naumonia, Vanderwaltozyma and Zygotoruspora, FEMS Yeast Res., 4, 233–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Langkjær R.B., Casaregola S., Ussery D.W., Gaillardin C., Piškur J.. 2003, Sequence analysis of three mitochondrial DNA molecules reveals interesting differences among Saccharomyces yeasts, Nucleic Acids Res., 31, 3081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bonnefoy N., Fox T.D.. 2000, In vivo analysis of mutated initiation codons in the mitochondrial COX2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fused to the reporter gene ARG8m reveals lack of downstream reinitiation, Mol. Gen. Genet., 262, 1036–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bonnefoy N., Bsat N., Fox T.D.. 2001, Mitochondrial translation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae COX2 mRNA is controlled by the nucleotide sequence specifying the pre-Cox2p leader peptide, Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 2359–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dubot A., Godinot C., Dumur V., et al. 2004, GUG is an efficient initiation codon to translate the human mitochondrial ATP6 gene, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 313, 687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akao T., Yashiro I., Hosoyama A.. et al. 2011, Whole-genome sequencing of sake yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Kyokai no. 7, DNA Res., 18, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marsico A., Scheubert K., Tuukkanen A., et al. 2009, MeMotif: a database of linear motifs in α-helical transmembrane proteins, Nucleic Acids Res., 38, D181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Belfort M., Roberts R.J.. 1997, Homing endonucleases: keeping the house in order, Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3379–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stoddard B.L. 2011, Homing endonucleases: from microbial genetic invaders to reagents for targeted DNA modification, Structure, 19, 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Watts T., Khalimonchuk O., Wolf R.Z., Turk E.M., Mohr G., Winge D.R.. 2011, Mne1 is a novel component of the mitochondrial splicing apparatus responsible for processing of a COX1 group I intron in yeast, J. Biol. Chem., 286, 10137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Turk E.M., Das V., Seibert R.D., Andrulis E.D.. 2013, The mitochondrial RNA landscape of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PLoS ONE, 8, 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dunin-Horkawicz S., Feder M., Bujnicki J.M.. 2006, Phylogenomic analysis of the GIY-YIG nuclease superfamily, BMC Genomics, 7, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cho Y.R., Palmer J.D.. 1999, Multiple acquisitions via horizontal transfer of a group I intron in the mitochondrial cox1 gene during evolution of the Araceae family, Mol. Biol. Evol., 16, 1155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Goddard M.R., Burt A.. 1999, Recurrent invasion and extinction of a selfish gene, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 96, 13880–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Delahodde A., Goguel V., Becam A.M., Creusot F., Banroques J., Jacq C.. 1989, Site specific DNA endonuclease and RNA maturase activities of two homologous intron encoded proteins from yeast mitochondria, Cell, 56, 431–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Petersen R.F., Langkjar R.B., Hvidtfeldt J., et al. 2002, Inheritance and organisation of the mitochondrial genome differ between two Saccharomyces yeasts, J. Mol. Biol., 318, 627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Talla E., Anthouard V., Bouchier C., Frangeul L., Dujon B.. 2005, The complete mitochondrial genome of the yeast Kluyveromyces thermotolerans, FEBS Lett., 579, 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haugen P., Simon D.M., Bhattacharya D.. 2005, The natural history of group I introns, Trends Genet., 21, 111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stoddard B.L. 2006, Homing endonuclease structure & function, Q. Rev. Biophys., 38, 49–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Edgell D.R. 2009, Selfish DNA: homing endonucleases find a home, Curr. Biol., 19, R115–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Belfort M. 2003, Two for the price of one: a bifunctional intron-encoded DNA endonuclease-RNA maturase, Genes Dev., 17, 2860–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J.B., et al. 2011, CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins, Nucleic Acids Res., 39, D225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fisk D.G., Ball C.A., Dolinski K., et al. 2006, The Saccharomyces Genome Database Project: Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C genome annotation: a working hypothesis, Yeast, 23, 857–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee C., Kim K.H., Cohen P.. 2016, MOTS-c: a novel mitochondrial-derived peptide regulating muscle and fat metabolism, Free Radical Biol. Med., 100, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lee C., Zeng J., Drew B.G., et al. 2015, The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance, Cell Metab., 21, 443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lecrenier N., Foury F.. 2000, New features of mitochondrial DNA replication system in yeast and man, Gene, 246, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Weiller G., Schueller C.M.E., Schweyen R.J.. 1989, Putative target sites for mobile G + C rich clusters in yeast mitochondrial DNA: single elements and tandem arrays, Mol. Gen. Genet., 218, 272–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. de Zamaroczy M., Bernardi G.. 1986a, The GC clusters of the mitochondrial genome of yeast and their evolutionary origin, Gene, 41, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Christianson T., Edwards J., Levens D., Locker J., Rabinowitz M.. 1982, Transcriptional initiation and processing of the small ribosomal RNA of yeast mitochondria, J. Biol. Chem., 257, 6494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Osinga K.A., De Vries E., Van der Horst G.T., Tabak H.F.. 1984a, Initiation of transcription in yeast mitochondria: analysis of origins of replication and of genes coding for a messenger RNA and a transfer RNA, Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 1889–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schäfer B. 2005, RNA maturation in mitochondria of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, Gene, 354, 80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Osinga K.A., De Vries E., Van der Horst G., Tabak H.F.. 1984b, Processing of yeast mitochondrial messenger RNAs at a conserved dodecamer sequence, EMBO J., 3, 829–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hofmann T.J., Min J., Zassenhaus H.P.. 1993, Formation of the 3′ end of yeast mitochondrial mRNAs occurs by site-specific cleavage two bases downstream of a conserved dodecamer sequence, Yeast, 9, 1319–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Freel K.C., Friedrich A., Hou J., Schacherer J.. 2014, Population genomic analysis reveals highly conserved mitochondrial genomes in the yeast species Lachancea thermotolerans, Genome Biol. Evol., 6, 2586–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wu B., Buljic A., Hao W.. 2015, Extensive horizontal transfer and homologous recombination generate highly chimeric mitochondrial genomes in yeast, Mol. Biol. Evol., 32, 2559–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gaillardin C., Neuveglise C., Kerscher S., Nicaud J.M.. 2012, Mitochondrial genomes of yeasts of the Yarrowia clade, FEMS Yeast Res., 12, 317–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bouchier C., Ma L., Creno S., Dujon B., Fairhead C.. 2009, Complete mitochondrial genome sequences of three Nakaseomyces species reveal invasion by palindromic GC clusters and considerable size expansion, FEMS Yeast Res., 9, 1283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Procházka E., Poláková S., Piškur J., Sulo P.. 2010, Mitochondrial genome from the facultative anaerobe and petite-positive yeast Dekkera bruxellensis contains the NADH dehydrogenase subunit genes, FEMS Yeast Res., 10, 545–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Clark-Walker G.D. 1992, Evolution of mitochondrial genomes in fungi, Int. Rev. Cytol., 141, 89–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hittinger C.T. 2013, Saccharomyces diversity and evolution: a budding model genus, Trends Genet., 29, 309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kurtzman C.P., Mateo R.Q., Kolecka A., Theelen B., Robert V., Boekhout T.. 2015, Advances in yeast systematics and phylogeny and their use as predictors of biotechnologically important metabolic pathways, FEMS Yeast Res., 15, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Peris D., Langdon Q.K., Moriarty R.V., et al. 2016, Complex ancestries of lager-brewing hybrids were shaped by standing variation in the wild yeast Saccharomyces eubayanus, PLoS Genet., 12, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rainieri S., Kodama Y., Nakao Y., Pulvirenti A., Giudici P.. 2008, The inheritance of mtDNA in lager brewing strains, FEMS Yeast Res., 8, 586–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Almeida P., Goncalves C., Teixeira S., et al. 2014, A Gondwanan imprint on global diversity and domestication of wine and cider yeast Saccharomyces uvarum, Nat. Commun., 5, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Peris D., Sylvester K., Libkind D., Gonçalves P., Sampaio J.P., Alexander W.G., Hittinger C.T.. 2014, Population structure and reticulate evolution of Saccharomyces eubayanus and its lager-brewing hybrids. Mol. Ecol., 23, 2031–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.