Abstract

Background

The reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) is the only fully domesticated species in the Cervidae family, and it is the only cervid with a circumpolar distribution. Unlike all other cervids, female reindeer, as well as males, regularly grow cranial appendages (antlers, the defining characteristics of cervids). Moreover, reindeer milk contains more protein and less lactose than bovids’ milk. A high-quality reference genome of this species will assist efforts to elucidate these and other important features in the reindeer.

Findings

We obtained 615 Gb (Gigabase) of usable sequences by filtering the low-quality reads of the raw data generated from the Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform, and a 2.64-Gb final assembly, representing 95.7% of the estimated genome (2.76 Gb according to k-mer analysis), including 92.6% of expected genes according to BUSCO analysis. The contig N50 and scaffold N50 sizes were 89.7 kilo base (kb) and 0.94 mega base (Mb), respectively. We annotated 21 555 protein-coding genes and 1.07 Gb of repetitive sequences by de novo and homology-based prediction. Homology-based searches detected 159 rRNA, 547 miRNA, 1339 snRNA, and 863 tRNA sequences in the genome of R. tarandus. The divergence time between R. tarandus and ancestors of Bos taurus and Capra hircus is estimated to be about 29.5 million years ago.

Conclusions

Our results provide the first high-quality reference genome for the reindeer and a valuable resource for studying the evolution, domestication, and other unusual characteristics of the reindeer.

Keywords: Rangier tarandus, reindeer, caribou, genomics, whole genome sequencing, assembly, annotation

Background Information

The Cervidae is the second largest family in the suborder Ruminantia of the Artiodactyla, which are distributed across much of the globe in diverse habitats, from arctic tundra to tropical forests [1, 2]. Reindeer or caribou (Rangifer tarandus, NCBI Taxon ID: 9870) is the only species with a circumpolar distribution (present in boreal, tundra, subarctic, arctic, and mountainous regions of northern Asia, North America, and Europe). It is also the only cervid having been fully domesticated, although some other species have been attempted, such as the sika deer (Cervus nippon), which has been semi-domesticated for more than 200 years and still has strong wild nature. Antlers are the defining characteristic of male cervids, belonging to the secondary sexual appendage, which shed and regrow in each year throughout an animal's life. Interestingly, reindeer is the only cervid species in which females regularly grow antlers (Fig. 1). Furthermore, reindeer milk contains a greater amount of proteins and a lower amount of lactose compared with that of bovids [3]. Here, we report a high-quality reindeer reference genome using material from a Chinese individual, which will be useful in elucidating special characteristics of this cervid.

Figure 1:

Male (above) and female (below) Rangier tarandus individuals, the only cervid species in which both sexes are able to produce velvet antlers. Pictures courtesy of Yifeng Yang from the Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Data Description

Animal and sample collecting

Fresh blood was collected from a 2-year-old female reindeer of a domesticated herd maintained by Ewenki (also know as Evenks) hunter-herders in the Greater Khingan Mountains, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (50.77°N, 121.47°E). The sample was immediately placed in liquid nitrogen, and was then stored at –80°C for later analysis.

Library construction, sequencing, and filtering

Genomic DNA was extracted from the sample thawed from frozen blood using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Isolated genomic DNA was then used to construct 5 short-insert libraries (200, 250, 350, 400, and 450 bp) and 4 long-insert libraries (3, 6.5, 11.5, and 16 kb) following standard protocols provided by Illumina. Then, 150-bp paired-end sequencing was performed to generate 723.2 Gb of raw data, using a whole genome shotgun sequencing strategy on the Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform (Table S1). To improve the read quality, we trimmed low-quality bases from both sides of the reads and removed reads with more than 5% of uncalled (“N”) bases. Then reads of all libraries were corrected by SOAPec (version 2.03) [4]. Finally, clean reads amounting to 615 Gb were obtained for genome assembly.

Evaluation of genome size

The estimated genome size is 2.76 Gb according to k-mer analysis, based on the following formula: G = N*(L − 17 + 1)/K_depth (Fig. S1), where N is the total number of reads and K_depth is the frequency of reads occurring more often than others [5]. All the clean reads provide approximately ∼220-fold mean coverage.

Genome assembly

We used SOAPdenovo (version 2.04; SOAPdenovo2, RRID:SCR_014986) with optimized parameters (pregraph −K 79 −d 0; map -k 79; scaff -L 200) to construct contigs and original scaffolds [5]. All reads were aligned onto contigs for scaffold construction by utilizing the paired-end information. Gaps were filled using reads from 3 libraries (200, 250, and 350 bp) with GapCloser (version 1.12; GapCloser, RRID:SCR_015026) [6]. The final reindeer genome assembly is 2.64 Gb long, including 95.7 Mb (3.6%) of unknown bases, smaller than that of the domestic goat (Capra hircus, 2.92 Gb) [7] and similar to that of sheep (Ovis aries, 2.61 Gb) [8]. The contig N50 (>200 bp) and scaffold N50 (>500 bp) sizes are 89.7 kb and 0.94 Mb, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1:

Summary of genome assembly of Rangier tarandus

| Type | Scaffold (bp) | Contig (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number | 58 765 | 117 102 |

| Total length | 2 832 785 815 | 2 732 476 387 |

| N50 length | 986 392 | 91 805 |

| N90 length | 151 297 | 17 480 |

| Max length | 4 664 725 | 770 474 |

| GC content (%) | 41.24 | 40.98 |

Quality assessments

We used Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO; version 2.0) software to assess the genome completeness (BUSCO, RRID:SCR_015008) [9]. Our assembly covered 92.6% of the core genes, with 3803 genes being complete (Table S2). The feature-response curve (FRC; version 1.3.1) method [10] was then used to evaluate the trade-off between the assembly's contiguity and correctness. The results indicate that it has a similar accumulated curve compared with published high-quality assemblies for other ruminant genomes including cattle, goat, and sheep (Fig. S2). Subsequently, synteny analysis was applied to identify differences between the assembled genome and the domestic goat (Capra hircus) genome (Fig. S3); 83.95% of 2 genome sequences could be 1:1 aligned, and the average nuclear distance (percentage of different base pairs in the syntenic regions) was 7.18% (Fig. S4). In addition, the density of different types of break points (edges of structural variation) was about 69.88 per Mb (Table S3). These results suggest that the reindeer genome assembly has of a good level of contiguity and correctness.

Genome annotation

To annotate the reindeer genome, we initially used LTR_FINDER (LTR_Finder, RRID:SCR_015247) [11] and RepeatModeller (version 1.0.4; RepeatModeler, RRID:SCR_015027) [12] to find repeats. Next, RepeatMasker (version 4.0.5) [13] was used (with -nolow -no_is -norna -parallel 1 parameters) to search for known and novel transposable elements (TE) by mapping sequences against the de novo repeat library and Repbase TE library (version 16.02) [14]. Subsequently, tandem repeats were annotated using Tandem Repeat Finder (version 4.07b; with 2 7 7 80 10 50 2000 -d -h parameters) [15]. In addition, we used RepeatProteinMask software [13] with -no LowSimple -p value 0.0001 parameters to identify TE-relevant proteins. The combined results indicate that repeat sequences cover about 1.03 Gb, accounting for 39.1% of the reindeer genome assembly (Table S4).

The rest of the reindeer genome assembly was annotated using both de novo and homology-based gene prediction approaches. For de novo gene prediction, we utilized SNAP (version 2006-07-28), GenScan (GENSCAN, RRID:SCR_012902) [16], glimmerHMM (GlimmerHMM, RRID:SCR_002654), and Augustus (version 2.5.5; Augustus: Gene Prediction, RRID:SCR_008417) [17] to analyze the repeat-masked genome. For homology-based predictions, sequences encoding homologous proteins of Bos taurus (Ensemble 87 release), Ovis aries (Ensemble 87 release), and Homo sapiens (Ensemble 87 release) were aligned to the reindeer genome using TblastN (version 2.2.26; TBLASTN, RRID:SCR_011822) with an (E)-value cutoff of 1 e-5. Genwise (version wise2.2.0) [18] was then used to annotate structures of the genes. The de novo and homology gene sets were merged to form a comprehensive, non-redundant gene set using EVidenceModeler software (EVM, version 1.1.1), which resulted in 21 555 protein-coding genes (Table S5). We then compared the reindeer genome with species that were used in homology prediction, and there was no significant difference among the 4 species in gene length and exon length distribution (Fig. S5).

Next, we searched the KEGG, TrEMBL, and SwissProt databases for best matches to the protein sequences yielded by EVM software, using BLASTP (version 2.2.26) with an (E)-value cutoff of 1 e-5, and searched Pfam, PRINTS, ProDom, and SMART databases for known motifs and domains in our sequences using InterProScan software (version 5.18-57.0; InterProScan, RRID:SCR_005829) [19]. At least 1 function was assigned to 19 004 (88.17%) of the detected reindeer genes through these procedures (Table S6). Of them, 14 138 genes were used to do the gene ontology annotation (Fig. S6). The reads from short–insert length libraries then were mapped to the reindeer genome with BWA (version 0.7.12-r1039; BWA, RRID:SCR_010910) [20], then single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were called by SAMtools (version 1.3.1; SAMTOOLS, RRID:SCR_002105) [21]. Finally, we performed SnpEff (version 4.30) [22] to identify the distribution of SNV in the reindeer genome. Finally, a total of 3 353 347 SNVs were found in the genome of the reindeer (Table S7).

In addition, we predicted rRNA-coding sequences based on homology with human rRNAs using BLASTN with default parameters (BLASTN, RRID:SCR_001598). To annotate miRNA and snRNA genes, we searched the Rfam database (release 9.1) with Infernal (version 0.81; Infernal, RRID:SCR_011809) [23] and annotated tRNAs using tRNAscan-SE (version 1.3.1) software with default parameters (tRNAscan-SE, RRID:SCR_010835) [24]. The final results identified 159 rRNAs, 547 miRNAs, 1339 snRNAs, and 863 tRNAs (Table S8).

Species-specific genes and phylogenetic relationship

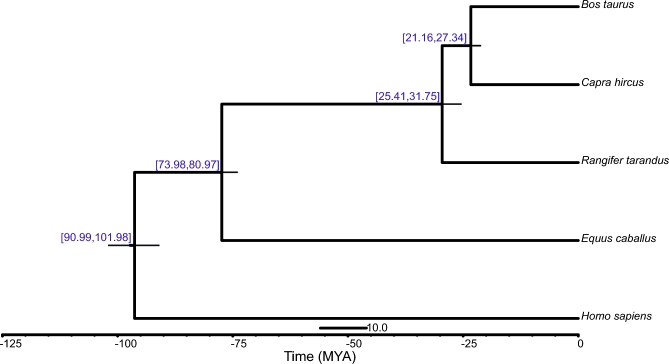

We clustered the detected reindeer genes in families by using OrthoMCL (OrthoMCL DB: Ortholog Groups of Protein Sequences, RRID:SCR_007839) [25] with an (E)-value cutoff of 1 e-5 and a Markov Chain Clustering with default inflation parameter in an all-to-all BLASTP analysis of entries for 5 species (Homo sapiens, Equus caballus, Capra hircus, Bos taurus, and Rangifer tarandus). The result showed that 335 gene families were specific to the reindeer (Fig. S7). Moreover, we identified 7505 single-copy gene families from these species and aligned coding sequences in the families using PRANK (version 3.8.31) [26]. Subsequently, 4D-sites (4-fold degenerated sites) were extracted to construct a phylogenetic tree by RAxML (version 7.2.8; RAxML, RRID:SCR_006086) [27] with a GTR+G+I model. Finally, phylogenetic analysis using PAML MCMCtree (version 4.5; PAML, RRID:SCR_014932) [28], calibrated with published timings of the divergence of the reference species [29, 30], indicated that Rangifer tarandus, Bos Taurus, and Capra hircus diverged from a common ancestor approximately 29.5 (25.41-31.75) MYA (Fig. 2). This is consistent with the previous findings from both fossil records and molecular phylogeny analysis [31, 32].

Figure 2:

Phylogenetic relationships of Rangier tarandus and 4 species based on 4-fold degenerated sites. The blue numbers in the square brackets above the nodes are the 90% confidence intervals of divergence time from the present.

Conclusion

In summary, we report the first sequencing, assembly, and annotation of the reindeer genome, which will be useful in analysis of the genetic basis of the unique characteristics of reindeer, and broader studies on ruminants.

Availability of supporting data

The raw sequence data have been deposited in the Short Read Archive (SRA) under accession numbers SRR5763125-SRR5763133. Assemblies, annotations, and other supporting data are also available in the GigaScience database, GigaDB [33].

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Supplementary tables_REVISED-1017.doc

Figure S1.pdf

Figure S2.pdf

Figure S3.pdf

Figure S4.pdf

Figure S5.pdf

Figure S6.pdf

Figure S7.pdf

Abbreviations

bp: base pair; BUSCO: benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs; EVM: EVidenceModeler; FRC: feature-response curves; Gb: giga base; kb:kilo base; Mb: mega base; MYA: million years ago; SNV: single nucleotide variant; TE: transposable element.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Z.P.L. collected the samples; Z.S.L., L.C., Z.P.L., Y.Z.Y., K.W., and H.X.B. analyzed the data; Z.S.L., Q.Q., and Z.P.L. wrote the manuscript; W.W. and G.Y.L. conceived the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31501984) and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (No. 1610342016026) to Z.P.L., and Talents Team Construction Fund of Northwestern Polytechnical University (NWPU) to Q.Q. and W.W. Special thanks to Nowbio Biotech Inc., Kunming, China, for its assistance with DNA library construction and sequencing.

References

- 1. Fernández MH, Vrba ES. A complete estimate of the phylogenetic relationships in ruminantia: a dated species-level supertree of the extant ruminants. Biol Rev 2005;80(2):269–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hassanin A, Delsuc F, Ropiquet A et al. Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactyla (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes. C R Biol 2012;335(1):32–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young W, Park GFWH. Handbook of Milk of Non-bovine Mammals. Ames, IA, USA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 2012;1(1):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li R, Fan W, Tian G et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 2010;463(7279):311–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li R, Zhu H, Ruan J et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res 2010;20(2):265–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bickhart DM, Rosen BD, Koren S et al. Single-molecule sequencing and chromatin conformation capture enable de novo reference assembly of the domestic goat genome. Nat Genet 2017;49(4):643–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang Y, Xie M, Chen W et al. The sheep genome illuminates biology of the rumen and lipid metabolism. Science 2014;344(6188):1168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P et al. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015;31(19):3210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vezzi F, Narzisi G, Mishra B et al. Reevaluating assembly evaluations with feature response curves: GAGE and assemblathons. PLoS One 2012;7(12):e52210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35(Web Server):W265–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Repeat Modeler http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html. Accessed 1 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2009. Chapter 4:Unit 4.10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Pavlicek A et al. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res 2005;110(1–4):462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 1999;27(2):573–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol 1997;268(1):78–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34(Web Server):W435–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res 2004;14(5):988–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014;30(9):1236–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heng L. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. 2013; arXiv:1303.3997 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009;25(16):2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w (1118); iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012;6(2):80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nawrocki EP, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics 2013;29:2933–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lowe TM, Chan PP. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(W1):W54–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 2003;13(9):2178–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Löytynoja A, Goldman N. An algorithm for progressive multiple alignment of sequences with insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102(30):10557–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014;30(9):1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 2007;24(8):1586–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hedges SB, Marin J, Suleski M et al. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. Mol Biol Evol 2015;32(4):835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Time Tree http://www.timetree.org/. Accessed 1 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. dos Reis M, Inoue J, Hasegawa M et al. Phylogenomic datasets provide both precision and accuracy in estimating the timescale of placental mammal phylogeny. Proc Royal Soc B Biol Sci 2012;279(1742):3491–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bibi F. A multi-calibrated mitochondrial phylogeny of extant Bovidae (Artiodactyla, Ruminantia) and the importance of the fossil record to systematics. BMC Evol Biol 2013;13(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li ZP, Lin ZS, Ba HX et al. Draft genomic data of the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). GigaScience Database 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.