Abstract

This paper describes the development, implementation, and outcomes of a quality improvement learning collaborative that aimed to better integrate chaplaincy with mental health care services at 14 participating healthcare facilities evenly distributed across the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DoD). Teams of healthcare chaplains and mental health professionals from participating sites sought to improve cross-disciplinary service integration in six key domains: screening; referrals; assessment; communication and documentation; cross-disciplinary training; and role clarification. Both chaplains and mental health providers across the entire facilities at participating sites were significantly more likely post collaborative to report having a clear understanding of how to collaborate and to report using a routine process for screening patients who could benefit from seeing the other discipline. Foundational efforts to enhance cross-disciplinary awareness and screening practices between chaplains and mental health professionals appearing particularly promising.

Healthcare organizations have increasingly emphasized the importance of “patient-centered care,” care that the Institute of Medicine has defined as “respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values” and that ensures that “patient values guide all clinical decisions” (1). For many patients amid illness experiences, these individualized values are strongly influenced by religious and spiritual considerations (2). In healthcare organizations, the professionals most specialized to attend to patients’ religious and spiritual needs are chaplains. Given the growing scientific literature demonstrating significant, meaningful, and complex interrelationships between religion, spirituality, and mental health functioning (3), it is of both clinical and ethical importance to develop systems of integrated mental health and chaplain care that can be dynamically responsive to patients’ diverse needs.

Background

In 2010, the Departments of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Defense (DoD) jointly commissioned a large-scale mixed methods review of chaplains’ roles with respect to mental health care as part of the VA/DoD Integrated Mental Health Strategy (IMHS). The departments initiated IMHS at a time when many post-9/11 veterans were beginning to leave the military and enter the VA system, beckoning for a coordinated approach to a range of mental health issues facing veterans and service members. The focus on chaplains’ roles was one of a total of 28 different strategic actions launched by the departments as part of IMHS, with the aim of this specific strategic action being to conduct a “gap analysis” that: 1) assessed the current state of chaplaincy integration with mental health; and 2) proposed a more optimal future state.

The gap analysis was informed and interpreted with the help of a 38-member task group composed of mental health professionals, chaplains, and researchers from various levels (e.g., leadership and clinicians) across VA, DoD, and outside organizations. A survey of all full-time VA chaplains and all active duty DoD chaplains was conducted (N = 2,163), as was a series of site visits to 33 medical facilities across VA and DoD at which 201 mental health professionals and 195 chaplains participated in hour-long interviews. Findings from this project indicated that chaplains frequently saw veterans and service members with mental health problems (4), and that there was substantial room for improving integration of care services, with providers often being interested in improved integration of care services (5).

Recommendations from the mixed-methods assessment included providing broad cross-disciplinary education about the value of integration, developing an in-depth mental health sub-specialization training program for chaplains, and equipping leaders and clinicians at local facilities to champion and facilitate systems redesign efforts focused on improved integration. These three recommendations were packaged into a VA/DoD Joint Incentive Fund (JIF) proposal, which was funded and began in 2013. We describe here the third of these three recommendations, which utilized a learning collaborative model to help teams of mental health professionals and chaplains implement quality improvements.

Learning Collaborative Model

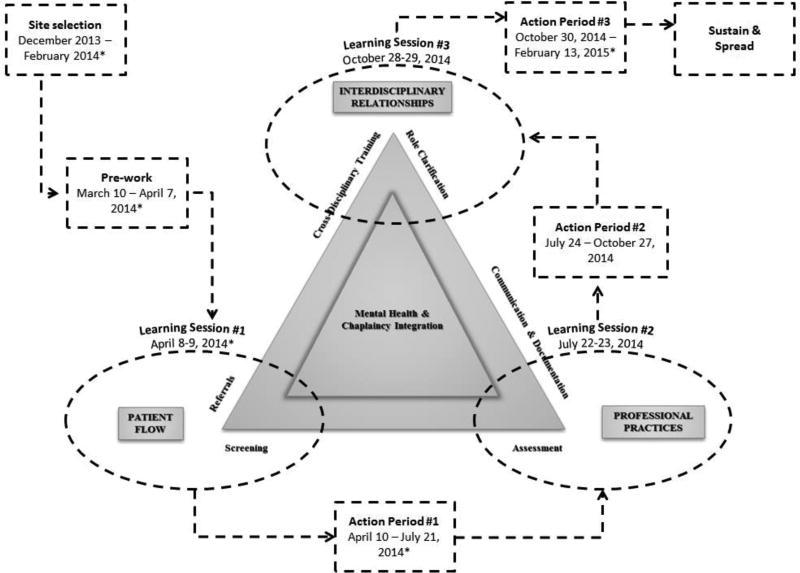

The Breakthrough Series learning collaborative model was first popularized in healthcare by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the late 1990s and has since been used as a key mechanism for spreading innovations in VA (6–8). The model used in our collaborative included six improvement domains – screening, referrals, assessment, communication and documentation, cross-disciplinary training, and role clarification (see Appendix Table 1 for further description of each aim) – which were focused on as part of three separate two-day learning sessions spread over the course of seven months. Each learning session was followed by an action period for teams to implement and monitor their improvements (see Appendix Figure 1 for a depiction of the learning collaborative model and process). During the action periods, teams implemented systems improvements using plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles. PDSA cycles involve developing an improvement idea (plan), implementing it (do), evaluating it (study), and then using the data to inform next steps (act; 6–8). Teams were not necessarily expected to develop and implement aims in all six domains. Instead, teams were assisted in mapping current processes at their facilities and in using that information to determine what areas were most in need of improvement.

Securing Participation

Seven of the 14 teams were from VA facilities. These teams were invited to participate based on recommendations from national VA chaplain leadership, findings from recent IMHS site visits to many of the VA facilities, knowledge of potential willingness to participate, and geographic diversity. The seven DoD teams were selected primarily from U.S. military medical treatment facilities – three Army, three Navy, and one Air Force – and were designated to participate by appropriate military Service-level leadership in mental health and chaplaincy who had been informed about the intentions of the collaborative. The process of securing participation was more challenging in DoD than in VA, likely owing to DoD consisting of three distinct branches that each needed to be engaged and local autonomy being highly constrained in DoD compared to VA, necessitating socialization with multiple layers of leadership.

Each facility’s core team consisted of a credentialed mental health professional and a chaplain, with each team being assigned a quality improvement coach (an expert in learning collaborative and systems improvement methods but not in the topical area). Quality improvement coaches provided logistical, systemic, and motivational support to teams and were supervised by the Veterans Engineering Resource Center (VERC) leadership team, which also provided industrial engineers, systems redesign expertise, and resources throughout the collaborative. Teams were geographically dispersed across the United States, most were located at large medical centers, and improvement efforts were focused across a range of clinical settings: posttraumatic stress disorder clinics were the most common for VA teams, and outpatient mental health settings were the most common in DoD (see Appendix Table 2 for details).

Evaluation

Evaluation in the learning collaborative consisted of: 1) teams monitoring their progress toward individualized goals as part of PDSA improvement cycles; and 2) surveys administered at baseline and post collaborative targeting all mental health professionals and chaplains at participating sites. All evaluation activities were certified as non-research quality improvement activities following both VA and DoD regulations.

Improvement Cycles

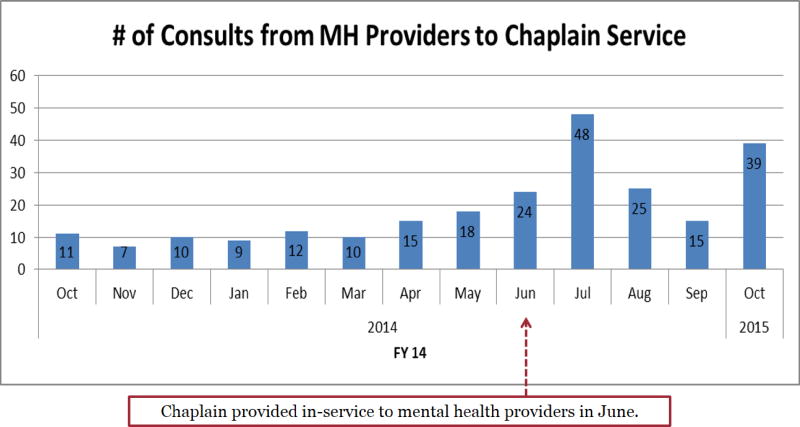

To track progress toward their goals as part of each PDSA cycle, each team developed individualized metrics, such as number of patients per month in a particular mental health clinic who were referred to chaplaincy (or vice versa), number of educational in-services held, or percentage of patients in a mental health clinic who screened positive for spiritual distress (and percentage of those who accepted a referral to chaplaincy). Teams were also encouraged to engage in improvement efforts in domains that related to the particulars of their context, setting, and larger local integration objectives. Teams successfully completed 76 PDSA cycles across all 6 collaborative domains, devoting the most effort in the domains of screening (17 total cycles), referrals (17), and role clarification (17), followed by communication and documentation (13), cross-disciplinary training (9), and assessment (3; see Appendix Figure 2 for a PDSA cycle example from one site).

Surveys

To evaluate potential spread of integrative mental health-chaplaincy practices from learning collaborative teams’ selected clinical settings to their broader facilities, baseline and post-collaborative electronic surveys were sent to the broader base of mental health providers (i.e., at least all psychiatrists and psychologists; social workers and others could be included depending on the mental health service makeup at a facility) and chaplains at facilities participating in the learning collaborative. Surveys evaluated perceptions of integration across the six quality improvement domains from the learning collaborative model. Compared to baseline, mental health professionals at participating facilities were significantly more likely post collaborative to report: using a routine process to identify patients that could benefit from chaplain services (p = .01); regularly communicating with chaplains to improve patient care (p = .01); having a clear understanding of how the disciplines can collaborate (p = .02); and having opportunities for joint training with chaplains when appropriate (p = .001). Chaplains at participating facilities were significantly more likely post collaborative to report having a clear understanding of how the disciplines can collaborate (p = .01), less likely to report benefitting from reading mental health providers’ notes (p = .03), and there was a trend for chaplains to be more likely to report using a routine process to identify patients that could benefit from seeing mental health (p = .05; see Appendix Table 3 for details).

Lessons Learned

The domains in which teams invested the most effort, including screening and role clarification, tended to be the areas in which facilities were most likely at the broader service line levels to evidence post-collaborative improvement. Follow-up analyses that separately considered data from VA and DoD teams indicated that the aims of the collaborative could be successfully implemented across both federal contexts in a manner that contributed to further spread across the broader services at participating facilities. VA teams evidenced somewhat more pronounced gains (or lack of difficulty) in a few key areas, which may be due to two reasons. First, VA teams were identified earlier and had a longer start-up period than DoD teams. Second, VA teams generally tended to have more autonomy than DoD teams to independently initiate change within their healthcare facilities.

An important attribute of this learning collaborative was that teams were strongly encouraged to formalize systematic changes from their quality improvement efforts within care coordination agreements. By the end of the collaborative, all teams either had such agreements signed by the heads of their mental health and chaplaincy departments or were working on accomplishing this. These agreements included articulating such things as how the disciplines would refer patients to one another, collaborate on interdisciplinary care teams, and conduct cross-disciplinary trainings. Findings from the IMHS site visits indicated that key persons (e.g., chaplains who took initiative to collaborate with mental health) were often responsible for integrative mental health and chaplaincy practices in the few places where this existed, and it was therefore easy for clinical integration to disintegrate along with staffing changes. Hence, particularly in military contexts where changes in duty assignments are routine, establishing care coordination agreements that are regularly revisited is important to ensure maintenance of systematic improvements.

Conclusion

Mental health and chaplain services are often not well integrated within healthcare organizations, but findings from the present study indicate that intentionally focusing quality improvement efforts in key domains can bring about improvements in how these clinical care services are organized and interact. Because these disciplines often intersect very little in officially structured capacities within many healthcare environments, initial efforts should focus on establishing the necessary foundations. Clarifying identities and services that the disciplines can provide, initiating even semi-structured efforts for identifying and screening patients that may benefit from seeing the other discipline, and providing a clear framework for how to make referrals are good foundational practices from which to potentially launch other collaborative endeavors (e.g., jointly led groups). Ultimately, it is such efforts that will lead to more patient-centered care and improved outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 14 teams that participated in this learning collaborative and the VA Employee Education System for data collection, cleaning, and management assistance. Funding was provided by a VA/DoD Joint Incentive Fund grant (JIF FY 2013 Enterprise Project #1). Evaluation of this effort was also supported by the Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410). Videos describing this learning collaborative in further detail and highlighting experiences from participating teams can be found at: https://www.mirecc.va.gov/mentalhealthandchaplaincy/Learning_Collaborative.asp

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1.

Mental health and chaplaincy learning collaborative model

* Dates reflect learning collaborative processes as initially conceptualized and as experienced by VA teams. Logistical challenges caused DoD teams to join the collaborative at a later date than originally anticipated. Hence, DoD teams did not attend the first learning session in person but instead participated in a two-day virtual “make-up” for learning session #1 on June 3–4, 2014. This resulted in a truncated first action period for DoD teams, but VA and DoD teams were then on the same calendar starting with learning session #2. Because of the delayed start for DoD teams, they were also allowed an extra 1–2 months beyond February 13, 2015 for an extended action period #3 during which to complete improvement efforts.

Appendix Figure 2.

Example from one site that tracked number of consults from mental health to chaplaincy

Appendix Table 1.

Mental health and chaplaincy learning collaborative improvement domains

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Screening | Evaluate current practices for screening patients for spiritual and mental health issues, with the intention of strengthening existing practices and / or implementing new research-informed screening practices where none exist. |

| Referrals | Strengthen and / or develop clearly articulated processes for referring patients between disciplines, including processes to contact the other discipline, communicate the core issue, articulate a basic care plan, and conduct follow-up. |

| Assessment | Develop, improve, and / or ensure standardized use of multidimensional spiritual and mental health assessments that contribute to making effective referrals and to providing relevant healthcare information to the other discipline. |

| Communication & Documentation | Establish regular communication practices, ideally as part of recurring integrated care team meetings, and document care and consults in a useful manner to the other discipline (at facilities where chaplain documentation of care is expected). |

| Cross-Disciplinary Training | Champion cross-disciplinary training opportunities, at a minimum to inform colleagues about the aims and rationale of the learning collaborative. |

| Role Clarification | Develop a better understanding of chaplain and mental health provider roles, culminating in the development of formal documentation of how mental health and chaplain services collaborate (e.g., care coordination agreements). |

Appendix Table 2.

Characteristics of sites participating in the learning collaborative

| Site and State | VA Facility Type1 / DoD Branch2 | Clinical Implementation Setting |

|---|---|---|

| VA Sites: | ||

| 1: Wyoming / Colorado | Vet Centers/2 VAMC | Couples Enrichment Program |

| 2: Ohio | 1a VAMC | PTSD Clinical Team |

| 3: Texas | 1a VAMC | Mental Health Trauma Services |

| 4: Indiana | 1a VAMC | PTSD Clinical Team |

| 5: Pennsylvania | 1a VAMC | Outpatient Mental Health / CBOCs |

| 6: Texas | 1a VAMC | PTSD Clinical Team |

| 7: Florida | 1a VAMC | Inpatient Psychiatry |

| DoD Sites: | ||

| 1: Florida | Navy | Outpatient Mental Health |

| 2: North Carolina | Navy | Outpatient Mental Health |

| 3: California | Navy | Emergency Room Mental Health |

| 4: Virginia | Army | Outpatient Mental Health |

| 5: Texas | Army | Outpatient Mental Health |

| 6: Hawaii | Army | Outpatient Mental Health |

| 7: Texas | Air Force | Outpatient Mental Health |

CBOC = Community Based Outpatient Clinic; VAMC = Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

VA uses the variables of patient population, clinical services offered, educational and research missions, and administrative complexity to categorize its facilities as level 1 (most complex), level 2 (moderately complex), or level 3 (least complex), and further subdivides level 1 into 1a, 1b, and 1c. FY2014 facility complexity levels are provided for VAMCs.

Bases on which military medical facilities were located are listed, with participating DoD facilities often being staffed by personnel from multiple branches as well as civilians.

Appendix Table 3.

Mental health provider and chaplain perceptions of integration at baseline and post learning collaborative

| Mental Health Providers | Chaplains | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N = 379)1 |

Post Collaborative (N = 210)1 |

Baseline (N = 77)1 |

Post Collaborative (N = 50)1 |

||

| Domain | Survey Item | n agree or strongly agree/total (%) | n agree or strongly agree/total (%) | ||

| Screening | 1. I use a routine process to identify patients that could benefit from other discipline2 services. | 154/377 (40.8%) | 109/209 (52.2%) | 34/75 (45.3%) | 31/49 (63.3%) |

|

| |||||

| Referrals | 2. I make frequent referrals to other discipline. | 70/377 (18.6%) | 46/209 (22.0%) | 23/75 (30.7%) | 21/48 (43.8%) |

|

| |||||

| 3. I receive frequent referrals from other discipline. | 33/371 (8.9%) | 21/206 (10.2%) | 23/76 (30.3%) | 19/49 (38.8%) | |

|

| |||||

| Assessment | 4. I regularly consider mental health issues as part of spiritual assessments. | - | - | 64/76 (84.2%) | 39/49 (79.6%) |

| I regularly consider religious and spiritual issues as part of mental health assessments. | 314/378 (83.1%) | 171/209 (81.8%) | - | - | |

|

| |||||

| Communication & Documentation | 5. I regularly communicate with other discipline to improve patient care. | 76/376 (20.2%) | 61/208 (29.3%) | 40/77 (51.9%) | 27/50 (54.0%) |

|

| |||||

| 6. I benefit from reading other discipline’s notes. | 128/362 (35.4%) | 80/199 (40.2%) | 60/76 (78.9%) | 28/46 (60.9%) | |

|

| |||||

| Role Clarification | 7. I have a clear understanding of how mental health and chaplain services can collaborate. | 186/365 (51.0%) | 125/204 (61.3%) | 52/75 (69.3%) | 43/48 (89.6%) |

|

| |||||

| Cross-Disciplinary Training | 8. I have opportunities for joint training with other discipline when appropriate. | 75/348 (21.6%) | 68/195 (34.9%) | 35/73 (47.9%) | 29/47 (61.7%) |

Two mental health providers were missing/don’t know for all of these items on the baseline survey. Five mental health providers were missing/don’t know for all of these items on the post-collaborative survey. Three chaplains were missing/don’t know for all of these items on the baseline survey, and this was the case for one chaplain for the post-collaborative survey. Numbers in the table are presented based on total number of participants who responded to an item, with the excluded missing values (including “don’t know) ranging from 0 to 9 for the variables presented.

Mental health professionals taking the survey rated themselves in relation to chaplains (e.g., “I make frequent referrals to chaplains). Chaplains taking the survey rated themselves in relation to mental health providers (e.g., “I make frequent referrals to mental health providers).

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense, or United States government.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jason A. Nieuwsma, VA Duke University Medical Center.

Dr. Heather A. King, VA Duke University Medical Center.

Dr. George L. Jackson, VA Duke University Medical Center.

Dr. Balmatee Bidassie, VA

Ms. Laura W. Wright, VA

Rev. William C. Cantrell, VA

Dr. Mark J. Bates, DoD

Dr. Jeffrey E. Rhodes, DoD

Ms. Brandolyn S. White, VA

Ms. Shannon J.L. Gatewood, DoD

Dr. Keith G. Meador, VA Vanderbilt University.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the quality chasm a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: Implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2001;76:1225–1235. doi: 10.4065/76.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackney CH, Sanders GS. Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieuwsma JA, Rhodes JE, Jackson GL, et al. Chaplaincy and mental health in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. 2013;19:3–21. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2013.775820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieuwsma JA, Jackson GL, DeKraai MB, et al. Collaborating across the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense to integrate mental health and chaplaincy services. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29:885–894. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilo CM. Improving care through collaboration. Pediatrics. 1999;103:384–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson GL, Powell AA, Ordin DL, et al. Developing and sustaining quality improvement partnerships in the VA: The colorectal cancer care collaborative. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(Suppl 1):38–43. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1155-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bidassie B, Davies ML, Stark R, et al. VA Experience in implementing patient-centered medical home using a breakthrough series collaborative. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29:563–571. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2773-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]