Abstract

OBJECTIVES

High school start times are a key contributor to insufficient sleep. This study investigated associations of high school start times with bedtime, wake time, and time in bed among urban teenagers.

DESIGN

Daily-diary study nested within the prospective Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study.

SETTING

20 US cities.

PARTICIPANTS

413 teenagers who completed ≥1 daily diary report on a school day.

MEASUREMENTS

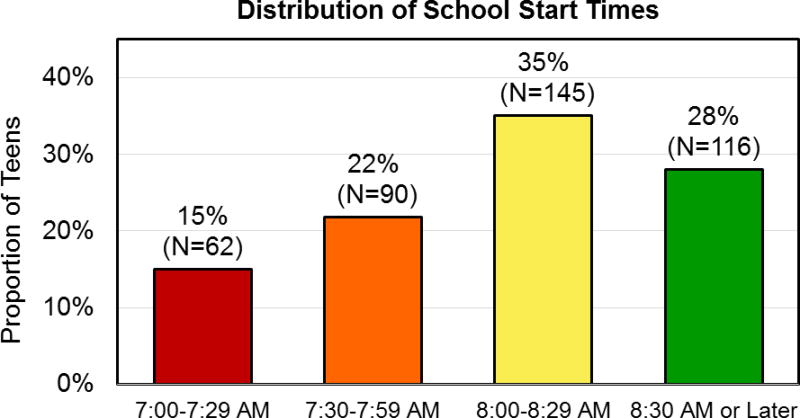

Participating teens were asked to complete daily diaries for 7 consecutive days. School-day daily diaries (3.8 ±1.6 entries per person) were used in analyses (N=1,555 school days). High school start time, the main predictor, was categorized as 7:00–7:29 AM (15%), 7:30–7:59 AM (22%), 8:00–8:29 AM (35%) and 8:30 AM or later (28%). Multilevel modeling examined the associations of school start times with bedtime, wake time, and time in bed. Models adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income, caregiver’s education, and school type.

RESULTS

Teens with the earliest high school start times (7:00–7:29 AM) obtained 46 minutes less time in bed on average compared to teens with high school start times at 8:30 AM or later (p<0.001). Teens exhibited a dose-response relationship between earlier school start times and shorter time in bed, primarily due to earlier wake times (p<0.05). Start times after 8:30 AM were associated with increased time in bed, extending morning sleep by 27–57 minutes (p<0.05) when compared to teens with earlier school start times.

CONCLUSION

Later school start times are associated with later wake times in our large, diverse sample. Teens starting school at 8:30 AM or later are the only group with an average time in bed permitting 8 hours of sleep, the minimum recommended by expert consensus for health and wellbeing.

Keywords: school start time, sleep, teens, adolescents, bedtime, wake time, high school

INTRODUCTION

The majority of teenagers (teens) in the United States (US) of America have insufficient sleep. Data collected from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 2015 showed that 73% of high school students reported less than 8 hours of sleep on school nights.1 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine Consensus Statement and the National Sleep Foundation’s Consensus Statement on sleep both recommend that teens obtain 8–10 hours of sleep per night.2,3

Melatonin secretion patterns, a reliable indicator of circadian timing, are delayed in both onset and offset relative to the dark/sleep period during puberty, triggering relatively later bedtimes and desired later wake times in teens.4,5 These physiological changes in circadian timing are incompatible with the daily life contexts of contemporary US teens. Social pressures, schoolwork, employment, familial schedules, extracurricular activities, and electronic devices are all factors that further delay teens’ circadian patterns, interfering with sleep.6,7 Furthermore, early school start times that require early morning wake times may present a temporal obstacle to sufficient nighttime sleep. For most teenagers, the ideal sleep/wake patterns would consist of an 11 PM bedtime and an 8 AM wake time.8

Adequate sleep in teens has been linked with overall academic success and improvements in memory, learning, and attention.9–11 Sufficient sleep in teens has also been linked with improved mood and health8 and decreased sports-related injuries,12 motor vehicle accidents,13 tardiness and school dropouts,8 and daytime sleepiness.8 Given the importance of sufficient sleep during this developmental period, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends middle and high schools begin after 8:30 AM.14

The purpose of this study was to examine the association of school start times (i.e., 7:00–7:29 AM, 7:30–7:59 AM, 8:00–8:29 AM, and 8:30 AM or later) on sleep timing and time in bed. Teen sleep timing and time in bed was measured by daily logs of bedtime, wake time and school start time (daily diaries) over one week. We had two specific hypotheses in this study. First, we hypothesized that, 1) compared to later school start times (i.e., 8:30 AM or later), earlier school start times would be associated with earlier wake times. Second, we hypothesized that 2) earlier school start times would be associated with shorter time in bed than later school start times, which we investigated using a time in bed variable constructed from the reports of bedtime and wake time. We did not expect to find a relationship between earlier school start times and earlier bedtimes due to the delayed circadian timing of sleep propensity typically seen during adolescence. Finally, to evaluate current consensus and clinical recommendations,2,3 we examined categorical start times before and after 8:30 AM, for their association with bedtime, wake time, and time in bed, hypothesizing that school start times after 8:30 AM would be associated with later wake times and longer time in bed.

METHODS

Data

Prospective data collection included daily diary data from a subsample of the parent study, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu). The parent study follows a longitudinal birth cohort of children born between 1998−2000 in 20 US cities, with an oversampling of non-marital births. The cohort was designed to create a national urban sample, randomly selecting cities with >200,000 people, then sampling hospitals within those cities, and then births within those hospitals.15 Mothers were initially interviewed in the hospital within 2 days of their child’s birth (baseline survey), and follow-up interviews were completed by parents (including fathers if available) and primary caregivers when the focal child was ages 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15. Eligibility for the age 15 wave of the study required participation in the original birth cohort and the age 9 wave of data collection. Separate primary caregiver surveys were used to collect information about the teen’s age and sex (baseline survey), and teen’s household income level, primary caregiver education level, and the type of school the teen attends (age 15 wave, primary caregiver survey). Teen’s report of race was collected from the age 15 teen survey wave.

Of the 3,055 eligible teens in the age 15 wave, a randomly-selected subset of 1,021 teens participated in this nested daily diary study. Participants were asked to complete web-based electronic daily diaries to report their nightly sleep and school start times.

The final analytic sample of this nested substudy included 413 high school students who provided at least one school-day of diary data during non-summer school months and provided complete daily diary data on school attendance, school start time, bedtime and wake time. The analytic sample was reduced due to teens who: 1) provided daily diary entries during summer months, (June, July, or August) (315 teens), 2) did not provide at least one school day of diary data (175 teens), 3) were homeschooled or did not report type of school (9 teens), 4) were in middle school (58 teens), and 5) did not provide data on school start time, or both bedtime and wake time, or 1 or more covariate variables (51 teens). The included and excluded teens within the nested study did not differ by sex, ratio of household income to poverty, primary caregiver education level, or school type. However, compared to teens who were excluded from analyses (608 teens), the teens who were included in the final analytic sample (413 teens) were approximately 1 month older (M=15.5 vs. M=15.4, p<0.05) and a lower proportion were white teens (14% vs 19%, p<0.05).

Compared to the teens in the parent study who did not participate in the nested study, the teens included in our nested substudy sample did not significantly differ with regard to poverty threshold, primary caregiver education level, and school type. Teens included in our nested substudy sample (n=413) differed with regard to age, sex, and race from the teens who participated in only the age 15 wave of the larger parent study. Teens in our nested substudy sample were younger (p<0.05) by about 7.5 months, consisted of more females (54% vs. 47%, p<0.05), and had more Hispanic/Latino teens (31% vs. 23%, p<0.001) than those who did not participate in the nested substudy.

Procedure

Teens were asked to complete an online daily diary each evening, beginning after 7:00 PM, during 7 consecutive days, including school days and non-school days during both the academic year and the summer, which we defined as September through May and June through August, respectively. On average, the sample completed this diary at 9:31 PM. Most participants completed the daily diary online through a computer, tablet, or smart phone; 6 did not have access to the internet and used a paper diary. Each diary entry took an average of 9.3 minutes to complete. Variables of interest collected from each diary entry included the previous night’s bedtime, the time the teen woke up in the morning, whether or not the teen went to school and the school start time. Among the total diary entries, we used only school-day entries during non-summer school months (1,555 school-day observations). Sociodemographic variables were obtained from primary caregivers (mostly mothers) during field interviews and also from teens at the age 15 survey.

Measures

Predictor

School Start Time (SST)

Each school day, the daily diary asked teens, “What time did your school day begin?” Responses were coded in the hour: minute AM/PM format. The Intra-Class Correlation (ICC) of the reported school start times indicated that there were 47 teens with any variation (one or more instance where the difference between SST and mode SST is nonzero, mean=0.99 hours, +/− 1.24 hours) in SST at the individual level (ICC=0.44) presumably due to occasional delays (e.g., weather, exams). The school start time variable was coded as a continuous variable. Analyses examined school start time as a continuous variable and investigated the associations with bedtime, wake time, and time in bed. Next, for ease of interpretation, school start times were further broken down into categories to compare teens with school start times before the recommended 8:30 AM start time with teens with school start times 8:30 AM or later. To further examine the associations of teens’ usual range of school start times during a week, we used the mode of school start times across school days and created a categorical indicator of school start times: 7:00≤x<7:30 AM was coded as 0, 7:30≤x<8:00 AM was coded as 1, 8:00≤x<8:30 AM was coded as 2, and x≥8:30 AM was coded as 3. The mode of the school start times, the most frequently reported school start time for each teen, was used to identify the most probable school start time without the influence of school delays.

Outcomes

Bedtime (BT) was determined from daily diary reports in the hour: minute AM/PM format. The diary asked “What time did you go to bed and try to fall asleep?” Clock times were then converted to decimal hour (e.g., 22.5 indicates 10:30 PM).

Wake time (WT) was determined from daily diary reports in the hour: minute AM/PM format. The diary asked “What time did you wake up to start your day?” Clock times were converted to decimal hour for wake time.

Time in bed (TIB) on school nights was calculated from the daily diary reported bedtimes and wake times and was coded in minutes/night.

Independent Measures

Covariates

We considered various potential confounder or adjustment variables, including sociodemographic background characteristics that are important predictors of sleep.16,17 Those characteristics included teen’s age in years, biological sex (1=male, vs. ref=female), race (Non-Hispanic White [reference], Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latino, multiracial, and other), and household poverty indicator based on ratio of income to poverty threshold (1=<49%, 2=50–99%, 3=100–199%, 4=200–299%, ref=>300%). The household poverty indicator was constructed from household income values gathered from the primary caregiver interview at year 15 compared to the national poverty threshold incomes established by the U. S. Census Bureau (http://www.census.gov/cps/data/povthresholds.html), which vary by household composition and year. In addition, we controlled for primary caregiver’s education, defined as completion of (1=some high school or less, 2=high school or equivalent, 3=some college or technical program, ref=college or graduate program) and school type (1=private or religious/parochial school, vs. ref=public school). We also controlled for daily-level school start times (centered at the person-level mode) to consider the associations of occasional variation in school start times within a teen on sleep variables, however 89% of teens had no change in school start time reported in their daily diary.

Statistical Analysis

We used multilevel modeling (Proc Mixed) in SAS 9.4 to take into account the clustered data structure. Repeated school-day observations were clustered within 413 teens. Teens provided multiple school-days’ reports, resulting in 1,555–1,560 total school-day observations (observations differed slightly due to missing reports of bedtime or wake time).

Evaluating one or more school days for each teen allowed us to test how school start times are linked to teens’ sleep on a daily basis. This can provide a more accurate picture of the association of day-to-day school start times and teens’ sleep than a single recall of typical sleep timing in the past month or year. The use of multilevel modeling also allowed us to consider potential daily changes in time in bed and sleep timing due to occasional variation in school start times at the within-teen level.

To test our first hypothesis, we examined the independent association of school start times with teens’ bedtimes (Model 1) and with teens’ wake times (Model 2), after controlling for covariates (i.e., age, sex, race, household poverty, primary caregiver education, and school type). To test our second hypothesis, we examined the associations of school start times with the teens’ amount of time in bed (Model 3) after controlling for the same covariates as Model 1 and Model 2.

RESULTS

Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlations among all variables used in this study. The average teen age was 15.5 years (SD=0.6, Range=14.6–17.6 years). About half were boys (46%), and the majority were ethno-racial minorities (see Table 1 for full descriptive results). The household income for 29% of the sample was below the poverty threshold, and approximately 35% of primary caregivers completed high school or less education. The sample was predominantly (89%) comprised of public school students, versus private, parochial, or religious school students (11%). After excluding non-school days and incomplete diary entries, the mean ± SD number of diary day entries was 3.8 ±1.6 school days. Of teens who completed the daily diary on one more school days, 12% logged 1 school day, 8% logged 2 school days, 18% logged 3 school days, 24% logged 4 school days, 26% logged 5 school days, 9% logged 6 school days and 2% logged 7–10 school days. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of teens in the sample across school start times, 7:00–7:29 AM (15%), 7:30–7:59 AM (22%), 8:00–8:29 AM (35%) and 8:30 AM or later (28%). The distribution of observations (school days included in multilevel modeling) from teens in each category was 7:00–7:29 AM (237 school days, 15%), 7:30–7:59 AM (340 school days, 22%), 8:00–8:29 AM (542 school days, 35%) and 8:30 AM or later (436 school days, 28%). The unadjusted mean bedtime was 11:11 PM (SD=1.1 hours, range 8:00 PM to 2:20 AM). The unadjusted mean wake time was 6:51 AM (SD=1.5 hours, range 1:01 AM to 10:39 AM). The unadjusted mean time in bed was 7.7 hours (SD=1.8 hours, range=0.1 to 12.5 hours).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by School Start Times

| School Start Times | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Sample |

7:00– 7:29 AM |

7:30– 7:59 AM |

8:00– 8:29 AM |

8:30AM or Later |

|

| N= | 413 | 62 | 90 | 145 | 116 |

| Mean Age | 15.5 | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 46.0% | 37.1% | 37.8% | 44.1% | 55.2% |

| Female | 54.0% | 62.9% | 62.2% | 55.9% | 44.8% |

| Race | |||||

| White | 14.3% | 19.4% | 30.0% | 10.3% | 4.3% |

| African-American | 45.3% | 58.1% | 46.7% | 37.9% | 46.6% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 31.0% | 11.3% | 10.0% | 40.7% | 45.7% |

| Multi-racial | 6.3% | 8.1% | 11.1% | 5.5% | 2.6% |

| Other | 3.1% | 3.2% | 2.2% | 5.5% | 0.9% |

| Income to Poverty Threshold % | |||||

| < 49% | 11.1% | 9.7% | 15.6% | 9.7% | 10.3% |

| 50–99% | 17.4% | 22.6% | 15.6% | 17.9% | 15.5% |

| 100–199% | 25.4% | 22.6% | 20.0% | 26.2% | 30.2% |

| 200–299% | 15.7% | 12.9% | 10.0% | 16.6% | 20.7% |

| > 300% | 30.3% | 32.3% | 38.9% | 29.7% | 23.3% |

| Caregiver's Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 18.6% | 11.3% | 11.1% | 23.5% | 22.4% |

| High school or equivalent | 16.7% | 17.7% | 17.8% | 12.4% | 20.7% |

| Some college or technical | 46.2% | 46.8% | 48.9% | 43.5% | 47.4% |

| College or more | 18.4% | 24.2% | 22.2% | 20.7% | 9.5% |

| Type of School | |||||

| Public School | 89.3% | 98.4% | 84.4% | 88.3% | 89.7% |

| Private/Religious School | 10.7% | 1.6% | 15.6% | 11.7% | 10.3% |

Figure 1. Distribution of Sample Teens’ High School Start Times.

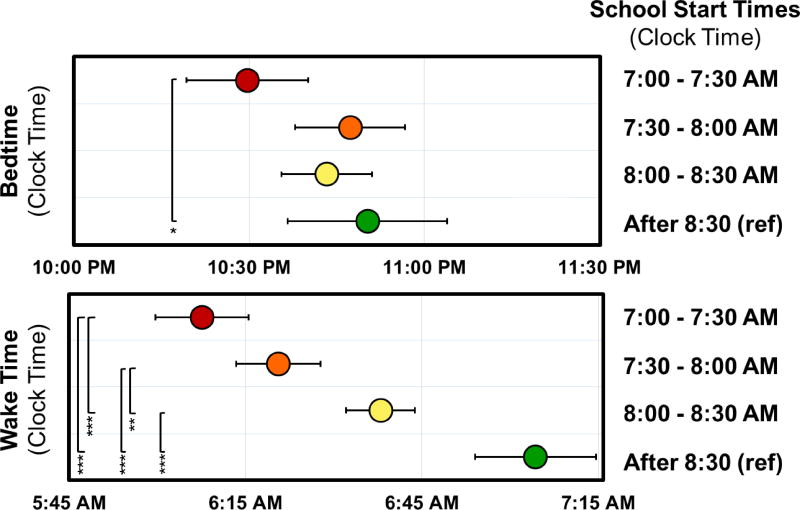

The association between school start times and sleep timing

Table 2 shows the model-adjusted, estimated bedtime per school start time category and Table 3 shows results of multilevel modeling that tested the associations of school start times with teens’ bedtimes (Model 1), after adjusting for covariates. Teens who had the earliest school start times, between 7:00 and 7:29 AM, went to bed significantly earlier (10:30 PM, p<0.05) than teens in the reference group of school start times after 8:30 AM (10:50 PM). The two middle categories of school start time, 7:30–7:59 AM and 8:00–8:29 AM were not significantly different from the reference group (10:47 PM and 10:43 PM, respectively), as presented in Figure 2. The difference in bedtime between the earliest school start time and the latest (after 8:30) averaged 20 minutes per school night. The associations between bedtime and a continuous school start time variable were also significant (B=0.194, SE=0.0839, p<0.05), where school start times one hour later were associated with a bedtime 11.6 minutes later (0.194 hours * 60 minutes/hour).

Table 2.

Model-Adjusted Estimated Means of Bedtime, Wake Time, and Time in Bed by School Start Time Categories from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study

| School Start Times | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7:00–7:29 AM | 7:30 AM–7:59 AM |

8:00 AM–8:29 AM |

8:30 AM or Later |

|||||

|

Estimated Mean (SD) |

Estimated Mean (SD) |

Estimated Mean (SD) |

Estimated Mean (SD) |

|||||

| Bedtime (Clock Time) | 10:30 PM | (10.45) | 10:47 PM | (9.44) | 10:43 PM | (7.78) | 10:50 PM | (13.65) |

| Wake Time (Clock Time) | 6:08 AM | (7.93) | 6:21 AM | (7.14) | 6:38 AM | (5.90) | 7:05 AM | (10.32) |

| Time in Bed (H:MM) | 7:24 | (13.40) | 7:31 | (12.17) | 7:45 | (9.98) | 8:09 | (17.37) |

Notes. Standard Deviations (SD) are in minutes. N=413; 1,560, 1,557, and 1,555 school days’ observations clustered within 413 teens were used for the multilevel models for bedtime, wake time, and time in bed, respectively (differences were due to missing responses in the variables). The models adjusted for age, sex, race, household income, primary caregiver’s education, and school type. Estimates reflect the interpretation of the Betas and Intercepts available in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of a Multilevel Model Examining the Association between School Start Times and Teens’ Bedtimes, Wake Times, and Time in Bed

| Bedtime (h) | Wake time (h) | Time in Bed (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Intercept | 22.84 (0.23)*** | 7.08 (0.17)*** | 8.16 (0.29)*** |

| School Start Times | |||

| 7:00–7:29 AM | −0.34 (0.17)* | −0.95 (0.13)*** | −0.76 (0.22)*** |

| 7:30–7:59 AM | −0.05 (0.16) | −0.73 (0.12)*** | −0.64 (0.20)** |

| 8:00–8:29 AM | −0.12 (0.13) | −0.44 (0.10)*** | −0.41 (0.17)* |

| 8:30 AM or later (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| Age (years) | 0.28 (0.10)** | 0.02 (0.07) | −0.22 (0.12) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | −0.23 (0.10)* | 0.03 (0.08) | 0.30 (0.13)* |

| Female (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| Race | |||

| Multi-racial | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.01 (0.18) | 0.26 (0.31) |

| African-American | 0.11 (0.16) | −0.05 (0.12) | −0.04 (0.21) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.16 (0.18) | 0.08 (0.14) | 0.06 (0.23) |

| Other | 0.72 (0.31)* | 0.07 (0.23) | −0.42 (0.39) |

| White (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| Daily Variation in School Start Times | 0.09 (0.04)* | 0.18 (0.04)*** | 0.17 (0.08)* |

| Income to Poverty Threshold % | |||

| <49% | −0.27 (0.19) | −0.05 (0.15) | 0.15 (0.25) |

| 50–99% | −0.23 (0.16) | −0.11 (0.12) | 0.40 (0.21) |

| 100–199% | −0.13 (0.15) | −0.05 (0.11) | 0.15 (0.19) |

| 200–299% | −0.10 (0.16) | −0.12 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.20) |

| ≥300% (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| Caregiver’s Education | |||

| Less than High School | −0.10 (0.20) | −0.04 (0.15) | −0.07 (0.26) |

| High School or Equivalent | −0.07 (0.19) | 0.10 (0.14) | −0.16 (0.24) |

| Some College or Tech | 0.21 (0.16) | 0.01 (0.12) | −0.37 (0.20) |

| College or Graduate School (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

| School Type | |||

| Attends Public School | 0.23 (0.16) | 0.07 (0.12) | −0.29 (0.21) |

| Private School (ref) | ------ | ------ | ------ |

Notes. N=413; 1,560, 1,557, and 1,555 school days’ observations clustered within 413 teens were used for the multilevel models for bed time, wake time, and time in bed, respectively (differences were due to missing responses in the variables). The corresponding units are decimal hours (e.g., 22.5 indicates 10:30 PM). The models adjusted for age, sex, race, household income, primary caregiver’s education, and school type.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Figure 2. Differences in Bedtime and Wake Time between School Start Times.

N=413; 1,560, 1,557, and 1,555 school days’ observations clustered within 413 teens were used for the multilevel models for bed time, wake time, and time in bed, respectively (differences were due to missing responses in the variables). Vertical bars begin and end at the groups that are significantly different, thus the absence of a bar reflects no statistical significance. Post-hoc test of bed timing revealed significance only in the relationship between the earliest school start time and the latest school start time (7:00–7:29 AM compared to 8:30 AM or later). Post-hoc tests of wake timing revealed that the differences in wake times between school start times 7:00–7:29 AM and 8:00–8:29 AM and between 7:30–7:59 AM and 8:00–8:29 AM were significant (p<0.001 and p<0.01, respectively). There was no significant difference between 7:00–7:29 AM and 7:30–7:59 AM. The models adjusted for age, sex, race, household income, primary caregiver’s education, and school type.

* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 2 shows the estimated wake time per school start time category and Table 3 shows results of multilevel modeling that tested the associations of school start times with teens’ wake times (Model 2), after adjusting for covariates. The results showed a dose-response relationship, with later school start times strongly associated with later wake times (p<0.001). For teens with school start times from 7:00–7:29 AM, 7:30–7:59 AM, 8:00–8:29 AM and 8:30 AM or later, wake times were 6:08 AM, 6:21 AM, 6:38 AM and 7:05 AM, respectively. A post-hoc test revealed that differences were also significant between the 7:00–7:29 AM group and 8:00–8:29 AM group and also between the 7:30–7:59 AM group and the 8:00–8:29 AM group (p<0.001 and p<0.01, respectively). These results are displayed in Figure 2. Analyses of school start time as a continuous variable with respect to wake time were also significant (B=0.580, SE=0.0620, p<0.001); for every school start time one hour later, the associated wake time is 34.8 minutes later (0.580 * 60 minutes/hour).

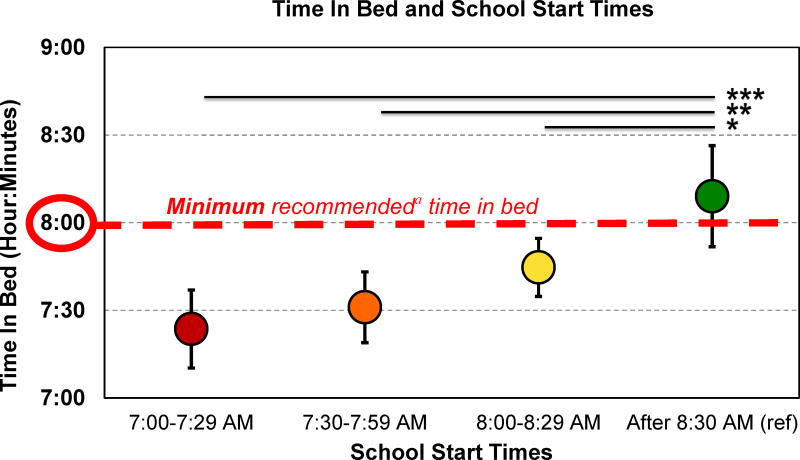

The association between school start times and time in bed

Table 2 presents calculated average time in bed per school start time category and Table 3 presents results of multilevel modeling that tested the associations of school start times with teens’ time in bed (Model 3), adjusting for differences due to covariates. Compared to teens who had later school start times (i.e., 8:30 AM or after), those who had earlier school start times consistently reported significantly (p<0.05) shorter time in bed by 25–46 minutes. These results, shown in Figure 3, also indicated a dose-response relationship between school start times and time in bed, with later school start times extending time in bed. In particular, teens who had very early school start times (i.e., 7:00–7:29 AM) had 46 minutes less sleep duration per school night than teens who had late school times (i.e., 8:30 AM or later). The two middle groups, 7:30–7:59 AM and 8:00–8:29 AM, reported significantly (p<0.05) shorter total time in bed by 38 and 24 minutes, respectively, when compared with the teens who start school at 8:30 AM or later, after adjusting for covariates (age, sex, race, household income, caregiver’s education, and school type). We found a consistent result when analyzing school start time as a continuous variable, indicating an association of 24.9 minutes (p<0.001) longer time in bed for each school start time one hour later. Potential moderating roles of sociodemographic characteristics (race and poverty level) were tested for all outcomes, but none had statistically significant (p<0.05) associations with bedtime, wake time, or time in bed.

Figure 3. Associations of High School Start Times and Teens’ Time in Bed.

Notes. N=413; 1,560, 1,557, and 1,555 school days’ observations clustered within 413 teens were used for the multilevel models for bed time, wake time, and time in bed, respectively (differences were due to missing responses in the variables). Post-hoc tests revealed that all categories of school times before 8:30 AM (7:00–7:29 AM, 7:30–7:59 AM, and 8:00–8:29 AM) spent less time in bed than the reference group, 8:30 AM or later. The models adjusted for age, sex, race, household income, primary caregiver’s education, and school type.

a The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the National Science Foundation recommend a minimum of 8 hours of sleep per night for teens.2,3

* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

DISCUSSION

This study examined the associations between school start times and teens’ bedtime, wake time, and time in bed using repeated daily diary reports across multiple school days. We found that school start times after 8:30 AM were associated with increased time in bed by 25–46 minutes, primarily due to later wake times relative to the wake times of earlier school start time groups. The students going to school after 8:30 AM were the only ones who obtained, on average, the time in bed corresponding to the minimum recommended sleep duration for teens established by both the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the National Sleep Foundation.2,3 Those going to school the earliest went to bed slightly earlier than the other groups, yet, due to an earlier school start time, achieved the shortest time in bed. Importantly, there was a strong dose-response relationship between earlier school start times and shorter time in bed. In analyses of school start time as a continuous variable, each hour later school start time corresponded to a later bedtime of 11.6 minutes, later wake time of 34.8 minutes and longer time in bed of 24.9 minutes. These results are consistent with research published from the National Comorbidity Study, which showed increases in sleep duration for later school start times in a nationally representative sample of 7,308 teens across 245 schools.18 By measuring daily bedtime, wake time, and time in bed on school nights, this study contributes to our understanding of how teens with school start times before and after the recommended 8:30 AM start time exhibit different sleep behaviors across the school week.

Previous studies have reported school start time as the strongest predictor of teens’ wake times on school days.19,20 Our study results were consistent with this literature and showed that school start time was strongly associated with teens’ wake times on school days. This finding was independent of sociodemographic characteristics found to be important for sleep behaviors.16,17 Teens with the earliest school start times went to bed 20 minutes earlier than teens with school start times after 8:30 AM. Moreover, with earlier school start times, wake times were progressively earlier. These linear changes in wake times help to explain the 24–46 minutes difference in time in bed between teens with early school start times and those with later school start times (after 8:30 AM).

Teens with school start times earlier than 8:30 AM obtained, on average, less than the 8 hours of minimum recommended time in bed (Figure 3).2,3 This result supports the recommendation by American Academy of Pediatrics that all high schools begin no earlier than 8:30 AM. Teens with school start times earlier than 8:30 AM may accrue “sleep debt” during school days due to the misalignment between school start times and their circadian drives.4,5 These teens may need to pay their “sleep debt” on non-school days. Studies found that on non-school days, teens’ wake times are consistently and significantly later than those on school days.7,21,22 Additionally, non-school night sleep durations are often longer to compensate for “sleep debt” accumulated during the school week23–25 and this gap widens as teens age.25 This social jet lag may further misalign teens’ circadian clocks from expected early wake timing on school days,21 interfering with having consistent sleep routines.

A common rebuttal to propositions for later school start times is the suggestion that teens instead just go to sleep earlier. This study found that teens with the earliest school start times were going to bed earlier than their peers, possibly due to a higher propensity for sleep from an early wake time that morning and the anticipation of an early wake time the following morning. Despite going to bed significantly earlier than their peers, these earlier bed times did not compensate for the time in bed lost in the morning, presumably due to early school start times. If we assume that teens in the earliest school start time group need to wake up, on average, at 6:08 AM to make it to school on time, they would have to go to bed before 10:08 PM to spend at least 8 hours in bed. This does not account for sleep onset latency, the amount of time it takes to fall asleep, and is still considerably earlier than the mean bedtime of 10:30 PM for this group.

In studies of delayed school start times, teens not only slept longer,13 but also exhibited decreased risk of motor vehicle accidents13 and better performance on tests of attention.26 Even delays of half an hour, from 8:00 AM to 8:30 AM, in accordance with the AAP recommendation14 were related to significant increases in sleep duration, an average extension of 45 minutes, with associated improvements in sleep satisfaction, motivation, alertness, mood and health and decreased daytime sleepiness.8,27 Longitudinal studies have further revealed an effect of delayed school start times on decreased dropout rates and tardiness, along with improved test scores and grades.8,28 Our findings add to this literature by demonstrating the inverse relationship between early school start times and high school students’ time in bed. The use of a national urban sample from 20 US cities located around the country allowed us to examine the associations of four different categories of school start times (7:00–7:29 AM, 7:30–7:59 AM, 8:00–8:29 AM, and 8:30 AM or later) with teen sleep, with previous literature suggesting that students in urban counties may see greater associations between later school start times and sleep.18 The teens in the study are part of a birth cohort that oversampled for non-marital births, increasing the likelihood of a single-parent family structure during development, which may be related to higher variability in bedtimes than two-parent households.29 The use of daily diary, completed by 68% of the sample for about 4 school days, also increases our confidence in interpreting the associations between school start times and teen sleep by providing repeated measurements.

The current study advances the literature by examining the associations of school start times with sleep timing and time in bed in three important ways. First, taking advantage of a daily diary design, this study uses repeated reports of sleep schedule and school start times over a school week to assess whether later school start times are associated with sleep timing and time in bed. This study design with repeated measures within the same individual teen allows for a more robust and valid estimate of both sleep measures30,31 and inclusive of variations from night to night.32 Second, much of the literature examined school start times across a single or a handful of school districts.33,34 The current study examines school start times in students living in 20 large US cities, a nation-wide sample particularly valuable for studying the associations of school start times in diverse ranges (i.e., 7:00–7:29 AM., 7:30–7:59 AM, 8:00–8:29 AM, 8:30 AM or later). Lastly, this study includes a greater proportion of “at risk” teens, as the study participants are part of a cohort of children of predominantly minority mothers from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Socioeconomic disparities in sleep are well documented in the literature.16,17,35,36

There are limitations in this study. Although we used a daily diary design that assessed sleep over multiple school days and the results show large and statistically significant associations, causality cannot be inferred. Longitudinal experimental studies implementing a delayed school start time intervention are better structured to test the causal effects of school start times on teen’s sleep at post-intervention. The use of self-reported data has the potential for common reporter bias on school start time and sleep.37 Future analyses might test the associations of school start times with actigraphically-assessed sleep measures. There is also the possibility that the days the teens completed the daily diary may not be reflective of a typical school week.32 Participants were instructed to complete the daily diary each evening in order to report events from that day, however, this presents the possibility of recall bias in reporting the previous night’s bedtime and the wake time from earlier that morning.

Finally, this sample was purposefully enriched with teens from low socioeconomic backgrounds and may not be generalizable to all teens in the US, but this sample is likely to capture those most vulnerable. Other variables not considered could also influence teen sleep, such as familial structure, household density, and other characteristics of the sleep environment. Furthermore, the 3,055 participants who participated in the age 15 follow-up, compared to 4,898 participants originally in the pre-birth cohort, may reflect a selection bias, including participants who are more likely to continually agree to participate in the study. The subset of teens comprising our final sample differed slightly by age, gender, and race when compared to teens in the parent Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study and differed slightly by age and race when compared with teens in the nested study who were excluded. The magnitude of these differences was modest. Future studies that include both low and high socioeconomic samples could test the moderating effects of sociodemographic and household characteristics in the link between school start times and teens' sleep.

CONCLUSION

We observed that teens who had early high school start times (7:00–7:29 AM, 7:30–7:59 AM, and 8:00–8:29 AM) reported earlier wake times and thus shorter time in bed, compared to teens with school start times at 8:30 AM or later. The time in bed for teens with school start times before 8:30 AM was less than the recommended minimum of 8 hours per night. Further research on the topic of school start times should be conducted at international, national and local levels to better inform the public health implications of school start times.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HD073352 (to LH), R01HD36916, R01HD39135, and R01HD40421, as well as a consortium of private foundations. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(6):1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D'Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for Pediatric Populations: A Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):785–786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep Time Duration Recommendations: Methodology and Results Summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of Adolescent Sleep: Implications for Behavior. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:276–291. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Richardson GS, Tate BA, Seifer R. An Approach to Studying Circadian Rhythms of Adolescent Humans. J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12(3):278–289. doi: 10.1177/074873049701200309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between Puberty and Delayed Phase Preference. Sleep. 1993;16(3):258–262. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Delayed Phase in Adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007;8(6):602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owens JA, Belon K, Moss P. Impact of Delaying School Start Time on Adolescent Sleep, Mood, and Behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):608–614. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. The Effects of Sleep Restriction and Extension on School-Age Children: What a Difference an Hour Makes. Child Dev. 2003;74(2):444–455. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Sleep and Student Performance at School. J Sch Health. 2005;75(7):248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl RE. Sleep, Learning, and the Developing Brain: Early-to-Bed as a Healthy and Wise Choice for School Aged Children. Sleep. 2005;28(12):1498–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheaton AG, Olsen EO, Miller GF, Croft JB. Sleep Duration and Injury-Related Risk Behaviors among High School Students--United States, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(13):337–341. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6513a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danner F, Phillips B. Adolescent Sleep, School Start Times, and Teen Motor Vehicle Crashes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(6):533–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Group ASW, Adolescence Co, Health CoS. School Start Times for Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):642–649. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reichman NE, Teitler JO, Garfinkel I, McLanahan SS. Fragile Families: Sample and Design. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2001;23(4/5):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale L. Who Has Time to Sleep? J Public Health (Oxf.) 2005;27(2):205–211. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE. Short Sleep Duration across Income, Education, and Race/Ethnic Groups: Population Prevalence and Growing Disparities During 34 Years of Follow-Up. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(12):948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paksarian D, Rudolph KE, He JP, Merikangas KR. School Start Time and Adolescent Sleep Patterns: Results from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey--Adolescent Supplement. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(7):1351–1357. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knutson KL, Lauderdale DS. Sociodemographic and Behavioral Predictors of Bed Time and Wake Time among Us Adolescents Aged 15 to 17 Years. J Pediatr. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes M, Davis K, Mancini M, Ruffin J, Simpson T, Casazza K. Setting Adolescents up for Success: Promoting a Policy to Delay High School Start Times. J Sch Health. 2016;86(7):552–557. doi: 10.1111/josh.12405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen M, Janssen I, Schiff A, Zee PC, Dubocovich ML. The Impact of School Daily Schedule on Adolescent Sleep. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):1555–1561. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Fallone G, Carskadon MA. Estimating Dim Light Melatonin Onset (Dlmo) Phase in Adolescents Using Summer or School-Year Sleep/Wake Schedules. Sleep. 2006;29(12):1632–1641. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.12.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rognvaldsdottir V, Gudmundsdottir SL, Brychta RJ, et al. Sleep Deficiency on School Days in Icelandic Youth, as Assessed by Wrist Accelerometry. Sleep Med. 2017;33:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Seifer R. Extended Nights, Sleep Loss, and Recovery Sleep in Adolescents. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139(3):301–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olds T, Blunden S, Petkov J, Forchino F. The Relationships between Sex, Age, Geography and Time in Bed in Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Data from 23 Countries. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(6):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lufi D, Tzischinsky O, Hadar S. Delaying School Starting Time by One Hour: Some Effects on Attention Levels in Adolescents. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(2):137–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheaton AG, Ferro GA, Croft JB. School Start Times for Middle School and High School Students - United States, 2011–12 School Year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(30):809–813. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6430a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carskadon MA, Acebo C. Regulation of Sleepiness in Adolescents: Update, Insights, and Speculation. Sleep. 2002;25(6):453–460. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.6.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troxel WM, Lee L, Hall M, Matthews KA. Single-Parent Family Structure and Sleep Problems in Black and White Adolescents. Sleep Med. 2014;15(2):255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary Methods: Capturing Life as It Is Lived. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S, Almeida DM. Daily Diary Design. In: Whitbourne SK, editor. Encyclopedia of adulthood and aging. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016. pp. 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libman E, Fichten CS, Bailes S, Amsel R. Sleep Questionnaire Versus Sleep Diary: Which Measure Is Better? Int J Rehab Health. 2000;5(3):205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahlstrom K, Dretzke B, Gordon M, Peterson K, Edwards K, Gdula J. Examining the Impact of Later School Start Times on the Health and Academic Performance of High School Students: A Multi-Site Study. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winsler A, Deutsch A, Vorona RD, Payne PA, Szklo-Coxe M. Sleepless in Fairfax: The Difference One More Hour of Sleep Can Make for Teen Hopelessness, Suicidal Ideation, and Substance Use. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(2):362–378. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale L, Emanuele E, James S. Recent Updates in the Social and Environmental Determinants of Sleep Health. Curr Sleep Med Rep. 2015;1(4):212–217. doi: 10.1007/s40675-015-0023-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hale L, Berger LM, LeBourgeois MK, Brooks-Gunn J. Social and Demographic Predictors of Preschoolers' Bedtime Routines. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(5):394–402. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ba0e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]