Summary

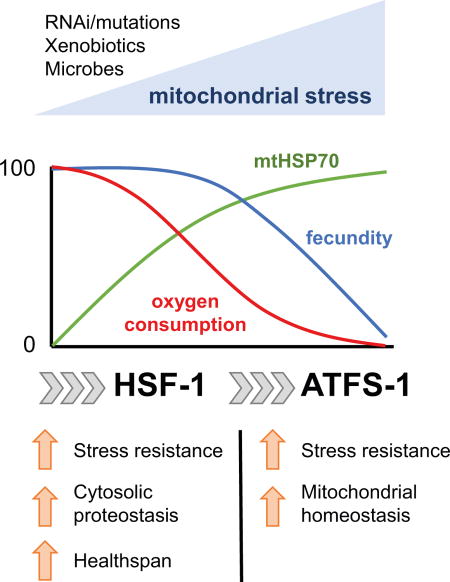

In Caenorhabditis elegans, the programmed repression of the heat shock response (HSR) accompanies the transition to reproductive maturity, leaving cells vulnerable to environmental stress and protein aggregation with age. To identify the factors driving this event, we performed an unbiased genetic screen for suppressors of stress resistance, and identified the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) as a central regulator of the age-related decline of the HSR and cytosolic proteostasis. Mild down-regulation of ETC activity, either by genetic modulation or exposure to mitochondria targeted xenobiotics, maintained the HSR in adulthood by increasing HSF-1 binding and RNA polymerase II recruitment at HSF-1 target genes. This resulted in a robust restoration of cytoplasmic proteostasis and increased vitality later in life, without detrimental effects on fecundity. We propose that low levels of mitochondrial stress regulate cytoplasmic proteostasis and healthspan during aging by coordinating the long-term activity of HSF-1 with conditions preclusive to optimal fitness.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Old age is the primary risk factor for many human diseases, however, the over-arching principles and molecular mechanisms that drive aging remain poorly understood ((Lopez-Otin et al., 2013). Aging has long been thought of as a stochastic process that is characterized by the gradual accumulation of cell damage. However, recent evidence suggests that aging arises, at least in part, from programmed events early in life that promote reproduction (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2014).

In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the ability to prevent metastable proteins from misfolding and aggregating fails early in adulthood, resulting in the appearance and persistence of protein aggregates in multiple tissues before animals have ceased reproduction (Ben-Zvi et al., 2009; David et al., 2010; Reis-Rodrigues et al., 2012; Walther et al., 2015).

Proteostasis is routinely maintained through the activity of constitutive and inducible stress response pathways. Among these, the transcription factor HSF-1 promotes the expression of molecular chaperones and enhances protein folding capacity in the cytosol/nucleus through the heat shock response (HSR). During C. elegans adulthood, the HSR undergoes rapid repression as animals commence reproduction, thereby leaving cells vulnerable to environmental stress and proteostasis collapse well before overt signs of aging are distinguishable (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a; Shemesh et al., 2013). This suggests that precise regulatory switches actively repress the HSR early in life as part of programs that promote reproduction at the cost of proteostasis (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a). However, it remains unclear which molecular and physiological processes drive the repression of the HSR and the loss of stress resistance in adulthood, how environmental factors influence this, and whether maintenance of proteostasis can be uncoupled from reduced fecundity.

To this end, we performed an unbiased genetic screen to identify genes whose knockdown maintains resistance to thermal stress and prevents repression of the HSR in reproductively active adults. We identified the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) as a robust determinant of the timing and severity of the decline in the HSR, and show that mild mitochondrial stress increases HSF-1 binding at target promoters, maintains the HSR, and preserves proteostasis in reproductively active animals. These beneficial effects were achieved without the severe physiological defects typically associated with impaired mitochondrial function, suggesting that modulation of mitochondrial activity is a physiologically relevant determinant of the timing of repression of the HSR and cytosolic proteostasis collapse with age.

Results

Complex IV inhibition increases stress resistance and maintains the HSR with age

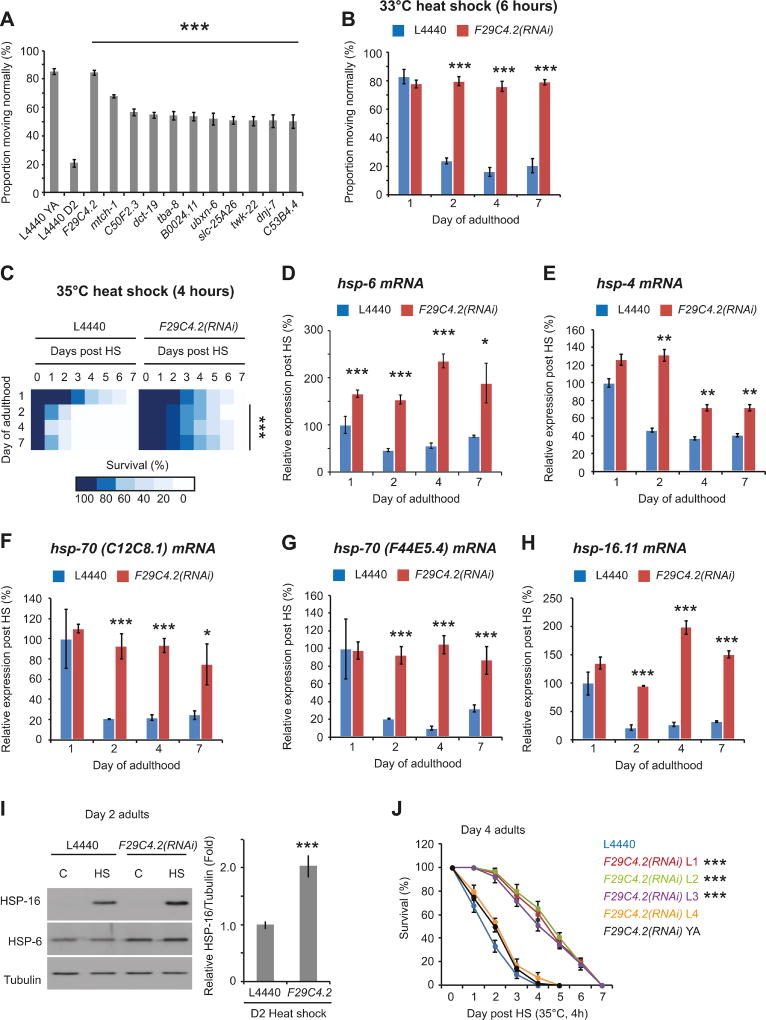

The activity of the HSR and thermal stress resistance decline dramatically between day 1 and day 2 of adulthood in C. elegans (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a). To identify pathways that control the collapse of stress resistance, we performed an unbiased genome-wide RNAi screen for genes whose knockdown maintained resistance to thermal stress in reproductive (day 2 – 24 hours post vulva formation) adults (Figure S1A). At day 1 of adulthood (4 hours post L4 molt), approximately 80% of animals move vigorously 48h post heat shock (HS) (Figure 1A). In contrast, on day 2, only 20% of adult animals exhibit normal movement following HS (Figure 1A). We identified 11 genes (Figure 1A, Table S1) whose knock-down restored stress resistance to at least 50% on day 2 of adulthood. Of these, knock-down of F29C4.2 (a predicted cytochrome C oxidase subunit orthologous to human COX6C and previously identified in a paraquat resistance screen (Kim and Sun, 2007)), fully restored stress resistance (Figure 1A). F29C4.2(RNAi) increased stress resistance through day 7 of adulthood (Figure 1B) and was effective in conferring protection against normally lethal stress conditions (Figures 1C and S1B), thus demonstrating that F29C4.2 is a potent modifier of the decline in cellular robustness with age.

Figure 1. Complex IV inhibition increases stress resistance and maintains the HSR in reproductively mature adults.

(A) RNAi clones that restore thermorecovery to at least 50% in reproductively active adults.

(B) Thermorecovery of L4440 or F29C4.2(RNAi) treated worms 48h following heat shock (HS) (33°C, 6h) on solid NGM plates at different days of adulthood.

(C) Survival of L4440 or F29C4.2(RNAi) treated worms following HS (35°C, 4h) on different days of adulthood. Related survival curves can be found in supplemental figure 1.

(D - H) Relative expression of (D) hsp-6, (E) hsp-4, (F) hsp-70(C12C8.1), (G) hsp-70(F44E5.4), and (H) hsp-16.11 relative to the house-keeping genes rpb-2 and cdc-42 in L4440 or F29C4.2(RNAi) treated animals following HS (33°C, 30 min) at different days of adulthood.

(I) Western blots of HSP-6, HSP-16, and tubulin at day 2 of adulthood in L4440 or F29C4.2(RNAi) treated animals 24h following exposure to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions at day 2 of adulthood. Levels of HSP-16 relative to tubulin were determined by densitometry and the mean of 3 biological replicates was plotted.

(J) Survival of animals following HS (35°C, 4h) on day 4 of adulthood following growth on L4440 or F29C4.2(RNAi) from the L1, L2, L3, or L4 larval stages, or the young adult (YA) stage of life.

Unless stated, all values plotted are the mean of 4 biological replicates and error bars denote SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by (A) one-way ANOVA with Tukey pairwise analysis of groups, (B - H) two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction and pair wise analysis of groups, (I) two-tailed Student’s t-test, and (J) two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni correction. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01 *** = p < 0.001.

ETC disruption is associated with increased longevity and improved health through activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) (Yun and Finkel, 2014). Consistent with this, F29C4.2(RNAi) significantly increased basal expression of the canonical UPRmt genes hsp-6 and hsp-60 on day 1 and day 2 of adulthood, and strongly activated an hsp-6p::gfp reporter (Figure S1C-E). F29C4.2(RNAi) also enhanced hsp-6 induction in response to heat shock on day 1 of adulthood and robustly maintained hsp-6 inducible expression thereafter (Figure 1D). These results indicate that F29C4.2(RNAi) constitutively activates, and enhances the responsiveness of, the UPRmt in adulthood, even before enhanced stress resistance is observed.

We next examined whether F29C4.2(RNAi) specifically augments the UPRmt, or has effects on the HSR and the endoplasmic reticulum UPR (UPRER), which both decline early in adulthood (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a; Taylor and Dillin, 2013). Basal expression of core cytosolic chaperones, canonical HSR genes, the ER inducible HSP70 homologue of the UPRER, and fluorescent reporters of the HSR or UPRER, were not induced upon F29C4.2(RNAi) (Figure S1C-E). However, upon exposure to HS, the levels of hsp-4, hsp-70(C12C8.1), hsp-70(F44E5.4), and hsp-16.11 were maintained from day 2 through day 7 of adulthood by F29C4.2(RNAi) (Figure 1E-H). In keeping with the enhanced HSR in day 2 adults, HSP-16 protein levels were also increased 2- fold in F29C4.2(RNAi) animals compared to L4440 controls following heat shock (Figure 1I).

Consistent with reports from other groups (Kim et al., 2016; Yoneda et al., 2004), our data demonstrate that ETC perturbation activates the UPRmt but does not constitutively activate the HSR or UPRER. Furthermore, we find that although F29C4.2(RNAi) results in activation of the UPRmt during adolescence, enhanced induction of cell stress response genes is only observed in reproductively active adults, suggesting that ETC perturbation influences proteostasis related pathways in a stage specific manner.

Lifespan assurance and activation of the UPRmt are dependent on changes in ETC activity during development (Dillin et al., 2002; Rea et al., 2007; Durieux et al., 2011). Therefore, we exposed animals to F29C4.2(RNAi) at distinct larval stages and measured stress resistance in post reproductive adults. Exposure to F29C4.2(RNAi) in early development (L1-L3 stage) was sufficient to fully maintain stress resistance through day 4 of adulthood, whereas stress resistance was not enhanced in animals placed on F29C4.2(RNAi) from the L4 or young adult stages onward (Figure 1J). These findings suggest that, like lifespan extension and activation of the UPRmt, the modulation of stress resistance with age is dependent on mitochondrial activity during development (Dillin et al., 2002; Rea et al., 2007; Durieux et al., 2011).

Disruption of various mitochondrial pathways enhances the HSR and stress resistance in reproductively mature adults

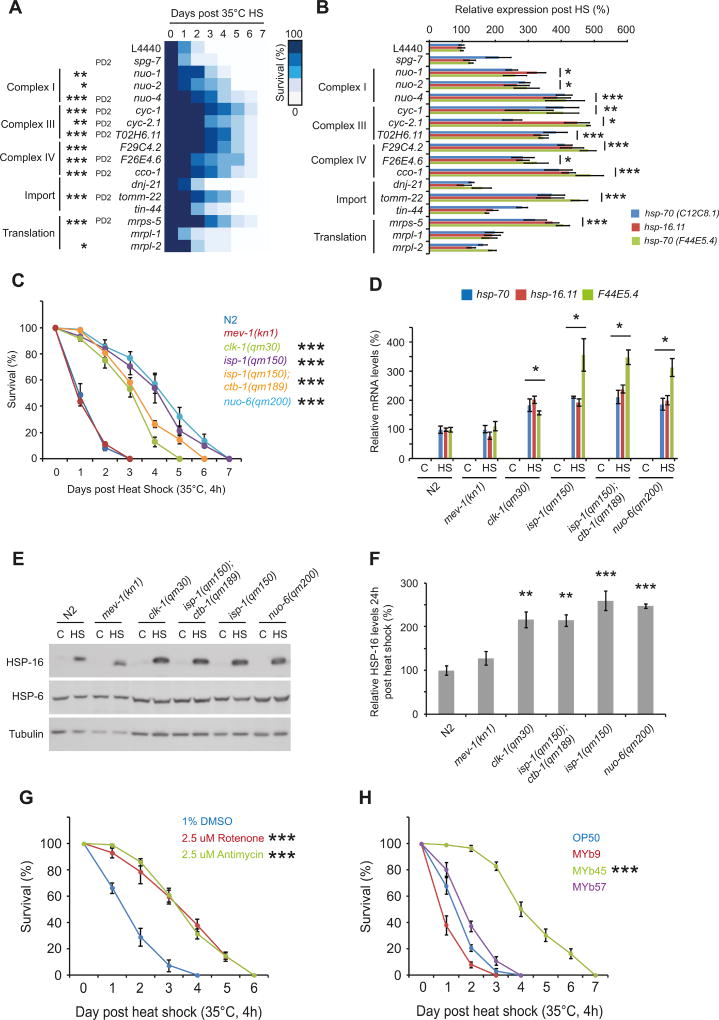

Enhanced stress resistance is intimately linked to longevity, and it has been shown that RNAi of many mitochondrial associated genes extends lifespan (Bennett et al., 2014; Dillin et al., 2002; Houtkooper et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2003). Therefore, we asked whether F29C4.2 was unique in its ability to enhance the HSR and maintain stress resistance. In our primary screen, several other genes encoding proteins with mitochondrial function (cco-1, nuo-4, cyc-1, tomm-22, and mrps-5) were identified but filtered out due to effects on development and/or fecundity. We therefore exposed animals to RNAi against subunits of complex I, complex III, and complex IV, or against genes integral to mitochondrial import, or mitochondrial protein synthesis, and assessed stress resistance in reproductively mature adults. In addition, animals were exposed to RNAi against the AAA metalloprotease coding gene, spg-7, which is known to induce the UPRmt (Haynes et al., 2010; Yoneda et al., 2004). We corrected for developmental delay by assessing resistance to thermal stress in animals that were physiologically age-matched (laying eggs for 24 hours prior to HS).

As expected, RNAi against all mitochondria associated genes induced hsp-6 expression (≥ 1.5-fold) at day 2 of adulthood (Figure S2A) but not the basal expression of HSR genes (Figure S2C). Upon exposure to heat stress, RNAi against subunits of complex I, III, and IV, or against tomm-22 and mrps-5, significantly increased stress resistance in reproductively active adults to a similar extent as observed for F29C4.2(RNAi) (Figures 2A and S2B). However, RNAi against dnj-21, tin-44, mrpl-1, mrpl-2, and spg-7 had little or no effect on stress resistance (Figure 2A, and S2B). These data suggest that stress resistance can be enhanced in reproductively mature adults through perturbation of multiple mitochondrial pathways, but that induction of mitochondrial stress is not always sufficient to maintain organismal stress resistance with age.

Figure 2. Multiple forms of mitochondrial perturbation maintain stress resistance and enhance the HSR in reproductively mature adults.

(A) Survival following heat shock (HS) (35°C, 4h) at standard chronological day 2 of adulthood, or physiological day 2 (PD2) of adulthood (animals allowed to develop longer before HS to correct for delayed onset of egg laying) in worms grown on empty vector control (L4440) or RNAi against mitochondria associated genes. Heat map is plotted as the mean survival at different days post HS for each condition. Related survival curves can be found in supplemental figure 2.

(B) Expression of hsp-70(C12C8.1), hsp-70(F44E5.4), and hsp-16.11 relative to the housekeeping genes rpb-2 and cdc-42 on day 2 of adulthood following HS (33°C for 30 min) in worms grown on L4440 or RNAi against mitochondria associated genes.

(C) Survival following HS (35°C, 4h) on day 2 of adulthood in wild type (N2) or mitochondrial mutant strains.

(D) Expression of hsp-70(C12C8.1), hsp-70(F44E5.4), and hsp-16.11 relative to the housekeeping genes rpb-2 and cdc-42 on day 2 of adulthood following HS (33°C, 30 min) in wild type and mitochondrial mutant animals.

(E) Western blots of HSP-6, HSP-16, and tubulin in wild type and mitochondrial mutant animals 24h post exposure to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions on day 2 of adulthood.

(F) Levels of HSP-16 relative to tubulin on day 2 of adulthood in wild type and mitochondrial mutant animals 24h post exposure to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions on day 2 of adulthood. Values plotted are the mean of 3 biological replicates.

(G) Survival following HS (35°C, 4h) on day 2 of adulthood in wild type animals exposed to vehicle control (1% DMSO), 2.5 uM rotenone, or 2.5 uM antimycin until the late L4 stage.

(H) Survival following HS (35°C, 4h) on day 2 of adulthood in wild type animals grown on OP50 E. coli, MYb9 achromobacter, MYb45 microbacterium, or MYb57 stenotrophomonas.

Unless stated, values plotted are the mean of 4 biological replicates and bars denote SEM. Statistical significance was calculated (A and B) relative to L4440 by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, (C) relative to N2 by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, (D and F) one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-analysis pair-wise comparison of groups, and (G and H) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction compared to 1% DMSO or OP50 control groups.

* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Consistent with their ability to enhance stress resistance, RNAi against subunits of complex I, III, and IV as well as tomm-22 and mrps-5 also enhanced the expression of all three HSR genes to a similar extent as F29C4.2(RNAi), while RNAi against dnj-21, tin-44, mrpl-1, mrpl-2, and spg-7 had only modest effects on the expression of hsp-70(C12C8.1), hsp-70(F44E5.4), or hsp-16.11 following HS (Figure 2A and B).

To extend beyond RNAi based experiments, we examined activation of the HSR and stress resistance at day 2 of adulthood in animals with loss-of-function mutations in mitochondrial genes (Baruah et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2001; Lakowski and Hekimi, 1996; Walter et al., 2011; Butler et al., 2010). Long-lived isp-1(qm150), nuo-6(qm200), isp-1(qm150);ctb-1(qm189), and clk-1(qm30) mutants, but not short-lived mev-1(kn1), gas-1(fc21), and ucr-2.3(pk732) mutants, all exhibited a greater than 3 fold increase in median survival, a 2 – 4 fold increase in the levels of hsp-70, F44E5.4, and hsp-16.11 mRNA, and a 2–3 fold increase in levels of HSP-16 protein compared to wild type worms following HS on day 2 of adulthood (Figures 2C-F and S2D). This was not simply due to developmental delay in the onset of reproductive maturity or reduced fecundity, as gas-1 and ucr-2.3 mutants both exhibited an increased time to gravid adulthood (in the case of ucr-2.3(pk732) mutants this was due to a delay in embryo formation once animals reached the first day of adulthood) and reduced brood size relative to N2 (Figure S2E and F).

In addition to genetic perturbation, mitochondrial stress is also induced by chemicals and some microbes (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, we hypothesized that the mitochondrial mediated maintenance of stress resistance in adulthood could constitute a physiologically relevant adaptive response to conditions that compromise mitochondrial activity. To test this, we examined stress resistance in reproductively active adults exposed to complex I (rotenone) or complex III (antimycin) inhibitors during development. We found that growth on solid media containing 2.5 µM rotenone or 2.5 µM antimycin exclusively during development activated the UPRmt without causing pronounced developmental delay (Figure S2G) and increased stress resistance approximately 2-fold compared to vehicle treated controls (Figure 2G).

Similarly, exposure to different microbes isolated from the natural environment of C. elegans have also been shown to activate the UPRmt (Liu et al. 2014; Samuel et al. 2016). Using three bacterial strains proposed to inhabit the natural C. elegans microbiome (Dirksen et al., 2016), we found that growth on the microbacterium MYb45 robustly activated the UPRmt (Figure S2G), whereas growth on the achromobacter strain MYb9 (increased brood size), or the stenotrophomonas strain MYb57 (no effect on brood size) did not activate the UPRmt (Figure S2G). Consistent with the ability to induce mitochondrial stress, growth on MYb45 but not MYb9 or MYb57 enhanced stress resistance nearly 3-fold compared to animals grown on the standard laboratory E. coli strain OP50 (Figure 2H).

Together, our data suggest that physiologically relevant conditions that cause mitochondrial stress can prevent the programmed loss of stress resistance that normally accompanies the commitment to reproductive maturity in early adulthood.

Physiological defects associated with mitochondrial perturbation can be uncoupled from beneficial effects on the HSR and stress resistance

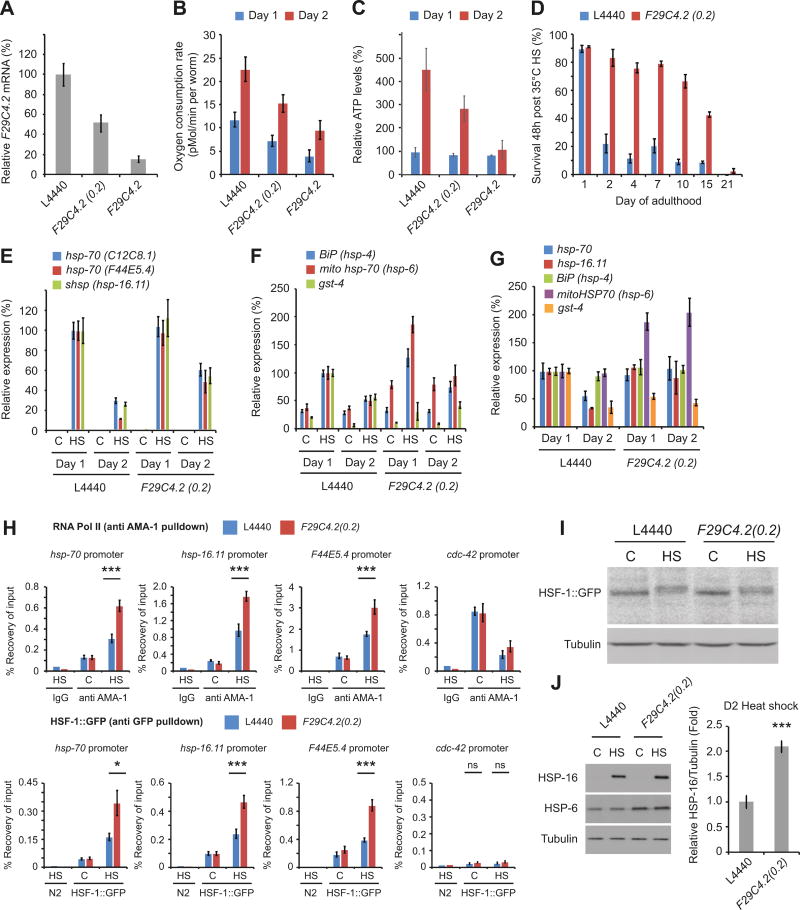

Although no developmental delay was observed, mitochondrial perturbation through F29C4.2(RNAi) did result in smaller animals, reduced brood size, and increased lethargy (Figure S3A and B). Previous studies have shown that dilution of ETC RNAi can significantly extend lifespan without many of the physiological defects observed upon full knockdown (Rea et al., 2007). Therefore, we adopted this approach with F29C4.2(RNAi) to determine whether the beneficial effects on stress resistance and the HSR could be separated from the deleterious consequences of ETC knockdown.

The level of F29C4.2 knockdown was tuned by exposing animals to undiluted F29C4.2(RNAi), or to F29C4.2(RNAi) diluted between 2 and 1000-fold with L4440 control bacteria (Figure S3A, C and D). Knockdown of F29C4.2 mRNA levels and activation of the UPRmt were dose dependent (Figure S3D), and the severity of changes in body size, motility, and brood size were negatively correlated with levels of F29C4.2 knockdown (Figure S3A). We found that a 5-fold dilution of F29C4.2(RNAi) (hereafter referred to as F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi)) maintained stress resistance to the same level as undiluted F29C4.2(RNAi) without significant reductions in motility or brood size, and with only a modest (20%) reduction in body size (although the period of egg-laying was slightly extended) (Figure S3A-E). F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) resulted in a 50–60% reduction in F29C4.2 mRNA levels and a 30% reduction in oxygen consumption rate (OCR) on day 2 of adulthood, compared to 80% and 50% reductions respectively, in undiluted F29C4.2(RNAi) animals (Figure 3A and B). OCR increased 2-fold between day 1 and day 2 of adulthood in all treatment groups, likely due to growth and increased oocyte mass during this time period (Figure 3B). Similarly, ATP levels also increased 3 – 5 fold in L4440 and F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals during this time period, but did not increase significantly in F29C4.2(RNAi) worms (Figure 3C). ATP levels were not altered compared to L4440 in F29C4.2(RNAi) or F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals on day 1 of adulthood. However, by day 2 of adulthood, ATP levels decreased by 80% and 30% in F29C4.2(RNAi) and F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals respectively (Figure 3C). Crucially, despite milder effects on animal physiology, OCR, and ATP levels, F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) still resulted in increased expression of hsp-6 and hsp-60 (Figure S3F) and maintained stress resistance through day 15 of adulthood (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. The gross physiological defects associated with mitochondrial perturbation can be uncoupled from enhanced stress resistance.

(A) F29C4.2 mRNA levels normalized to the house keeping genes rpb-2 and cdc-42 on day 2 of adulthood.

(B) Oxygen consumption rates at day 1 and day 2 of adulthood. Values plotted are the mean of 3 biological replicates.

(C) ATP levels at day 1 and day 2 of adulthood.

(D) Survival 48h following HS (35°C, 4h) on day 2 of adulthood.

(E - G) Expression of canonical HSR (C12C8.1, F44E5.4, hsp-16.11), UPRER (hsp-4), UPRmt (hsp-6) and oxidative stress response (gst-4) genes normalized to the housekeeping genes rpb-2 and cdc-42 on day 1 and day 2 of adulthood following exposure to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions.

(H) RNA polymerase II (AMA-1) (upper panels) and HSF-1::GFP ChIP (lower panels) followed by qPCR for hsp-70, hsp-16.11, F44E5.4, and cdc-42 promoters in day 2 adults exposed to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions.

(I) Western blots of HSF-1::GFP and tubulin in worms exposed to control or HS (33°C, 30 min) conditions on day 2 of adulthood. The slight shift in HSF-1 SDS-PAGE mobility corresponds to the well documented hyperphosphorylation of HSF-1 following HS.

(J) Western blots of HSP-16, HSP-6, and tubulin at day 2 of adulthood 24h following exposure to control conditions or HS (33°C, 30 min) at day 2 of adulthood. Levels of HSP-16 relative to tubulin were calculated from 3 biological replicates.

Unless stated, all values plotted are the mean of 4 biological replicates and bars denote SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by (H) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction followed by pair-wise analysis of groups and (J) two-tailed Student’s t-test.. * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by mitochondrial stress have been proposed to act as life lengthening signaling molecules (Yang and Hekimi, 2010). Levels of general ROS, H2O2, and protein carbonylation were significantly increased following treatment with F29C4.2(RNAi) (Figure S3G-I), consistent with mitochondrial dysfunction (Segref et al., 2014). Conversely, animals grown on F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) exhibited smaller increase in ROS on day 1 and day 2 of adulthood, and little to no difference in levels of H2O2, or protein carbonylation (Figure S3G-I), suggesting that maintenance of the HSR, enhanced stress resistance and preservation of proteostasis do not require substantial increases in ROS levels, and are not due to widescale oxidative damage to proteins (Figures S3G-I).

To determine whether increased stress resistance was still associated with an enhanced activity of stress response pathways, we exposed L4440 and F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals to HS at day 1 and day 2 of adulthood and quantified expression levels of HSR, UPRER, and UPRmt genes. F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) did not constitutively activate the HSR, or UPRER, or lead to enhanced induction of these genes upon HS at day 1 of adulthood (Figure 3E-G). Furthermore, although levels of the oxidative stress responsive gene gst-4 are enhanced by elevated ROS and chronic mitochondrial perturbation (Schaar et al., 2015), we did not observe activation of a gst-4p::gfp based reporter of the oxidative stress response or enhanced gst-4 expression in response to heat stress by F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi). Curiously, gst-4 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in day 1 adults (Figure 3F and G), suggesting that while F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) results in reduced oxygen consumption, this is not associated with elevated gst-4 expression, possibly as steady state ROS levels are not dramatically increased (Figure S3G and H) and/or because the ability to express gst-4 may be impaired. While F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) did not maintain the UPRER or oxidative stress response at day 2 of adulthood, the induction of HSR genes and HSP-16 protein levels were increased by 2–3 fold following HS on day 2 of adulthood (Figure 3E and J).

Repression of the HSR in reproductively active adults has been shown to be due to a reduced ability of HSF-1 to bind to target promoters and enhance transcription in response to heat shock (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a). Therefore we asked whether F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) could enhance the levels of HSF-1 and RNA Pol II at HSR promoters using animals expressing a single copy of HSF-1::GFP (Li et al., 2016). HSF-1::GFP animals exhibit an enhanced HSR and stress resistance in response to F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) (Figure S3J and K). Furthermore, HSF-1 and RNA Pol II levels were increased approximately 2-fold at HSR promoters in F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals following HS at day 2 of adulthood (Figure 3H), without significant changes in the expression, stability, or nuclear localization of HSF-1 (Figure 3I and Figure S3L and M).

Our data demonstrate that mitochondrial stress can be “tuned” to enhance the HSR and prevent the age-related decline in stress resistance without the burden of severe physiological defects. This suggests that the influence of mitochondria on age-related changes in non-mitochondrial stress resistance pathways represents a physiologically relevant strategy by which cells and organisms use environmental cues to coordinate the onset of reproduction and the decline of stress responses with age.

Mitochondrial stress prevents the age-dependent collapse of cytosolic proteostasis

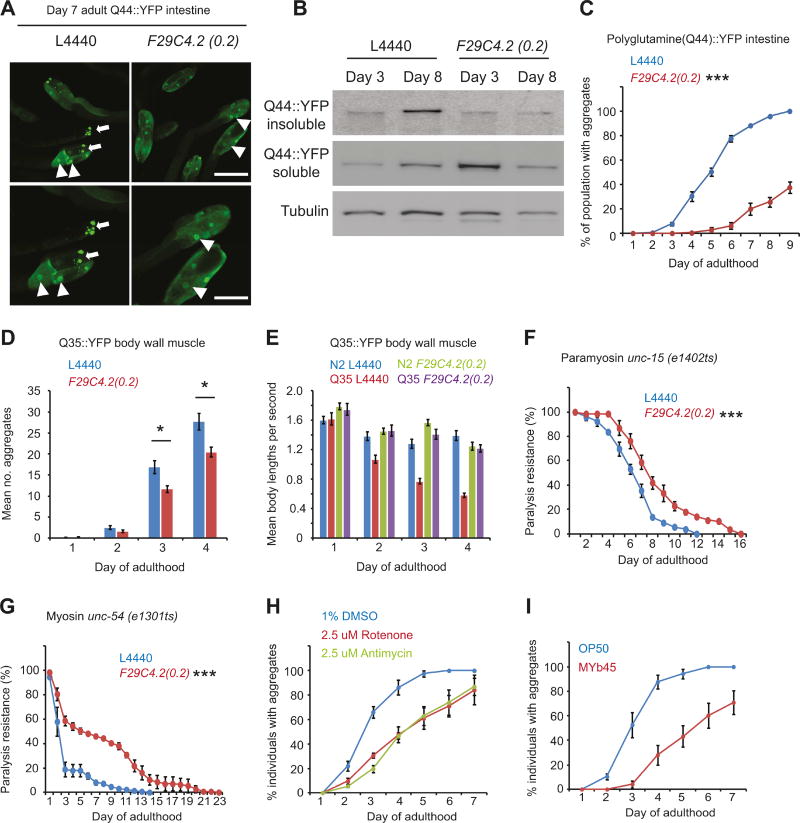

Coincident with the rapid decline in stress resistance, proteostasis also collapses dramatically in multiple tissues during early C. elegans adulthood (Ben-Zvi et al., 2009; David et al., 2010). Therefore, we asked whether mild mitochondrial perturbation could prevent proteostasis collapse in the cytosol with age using animals expressing endogenous metastable proteins or exogenous aggregation prone proteins in intestinal cells or body wall muscle cells.

Animals expressing 44 polyglutamine (polyQ) residues fused to YFP (polyQ(44)::YFP) in intestinal cells (Mohri-Shiomi and Garsin, 2008; Prahlad and Morimoto, 2011) show diffuse polyQ44::YFP fluorescence throughout the intestine on day 1 of adulthood, the intensity and localization of which is unaltered by F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) (Figure S4C). However, by day 7 of adulthood, greater than 80% of the population exhibits large SDS insoluble polyQ aggregates in the proximal intestinal cells (Figures 4A-C and S4C). Growth on F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) profoundly reduced the number of animals containing polyQ aggregates with age, and almost completely suppressed the formation of SDS insoluble polyQ aggregates in intestinal cells (Figure 4B and C) without affecting expression of the Q44::YFP transgene (Figure S4A). Although variable across samples, F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) treated animals exhibited a trend toward increased levels of soluble polyQ protein on day 3 of adulthood, possibly due to impairments in protein turnover (Segref et al., 2014; Livnat-Levanon et al., 2014). However, this did not affect the ability to suppress aggregate formation with age (Figures 4B and S4D).

Figure 4. Mitochondrial perturbation suppresses proteostasis collapse in the cytosol.

(A) Representative images of the proximal intestine of worms expressing 44 polyglutamine (polyQ) residues fused to YFP (vha-6p::polyQ(44)::yfp) on day 7 of adulthood. Triangles indicate nuclei and arrows indicate polyglutamine aggregates. Scale bars represent 250 µM (upper panels) and 100 µM (lower panels).

(B) Western blots of insoluble and soluble Q44::YFP, and tubulin at day 3 and day 8 of adulthood.

(C) Proportion of individuals exhibiting intestinal Q44::YFP aggregates at different days of adulthood.

(D) Number of Q35::YFP foci in body wall muscle cells of unc-54p::polyQ(35)::YFP animals at different days of adulthood.

(E) Motility of wild type (N2) animals and animals expressing Q35::YFP in body wall muscle cells (unc-54p::polyQ(35)::YFP) at different days of adulthood.

(F and G) Age-related paralysis in animals expressing endogenous metastable (F) paramyosin (unc-15(e1402ts)) or (G) myosin (unc-54(e1301ts)).

Unless stated, all values were the mean of 4 biological replicates and bars denote SEM. Statistical significance was calculated by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. * = p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001.

(H and I) Proportion of animals exhibiting intestinal Q44::YFP aggregates at different days of adulthood following (H) growth on vehicle control, 2.5 uM rotenone, or 2.5 uM antimycin during development (L1 to late L4) or, (I) growth on OP50 E. coli or MYb45 microbacteria.

Furthermore, F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) also suppressed polyQ(35)::YFP aggregation and toxicity in body wall muscle cells by 20% at day 3 and day 4 of adulthood without affecting expression of the Q35::YFP transgene (Figures 4D, E, and S4B), and delayed the onset of paralysis at permissive temperatures in animals harboring destabilizing point mutations in the essential muscle proteins paramyosin (unc-15ts) or myosin (unc-54ts) (Figure 4F and G), suggesting that mitochondrial activity is a general determinant of the timing and severity of proteostasis collapse with age in different tissues.

Finally, consistent with their ability to increase stress resistance, exposure to rotenone, antimycin, or the pathogen MYb45, reduced polyQ aggregation by 40–50% at days 3 – 5 of adulthood (Figures 4H and I, and S4E) compared to control treated animals. Although these effects were less profound than those observed with F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi), our data nevertheless suggest that mild mitochondrial stress from physiologically relevant xenobiotics and pathogens can reset cytosolic proteostasis collapse with age.

Mitochondrial perturbation enhances stress resistance and cytosolic proteostasis in an HSF-1 dependent manner

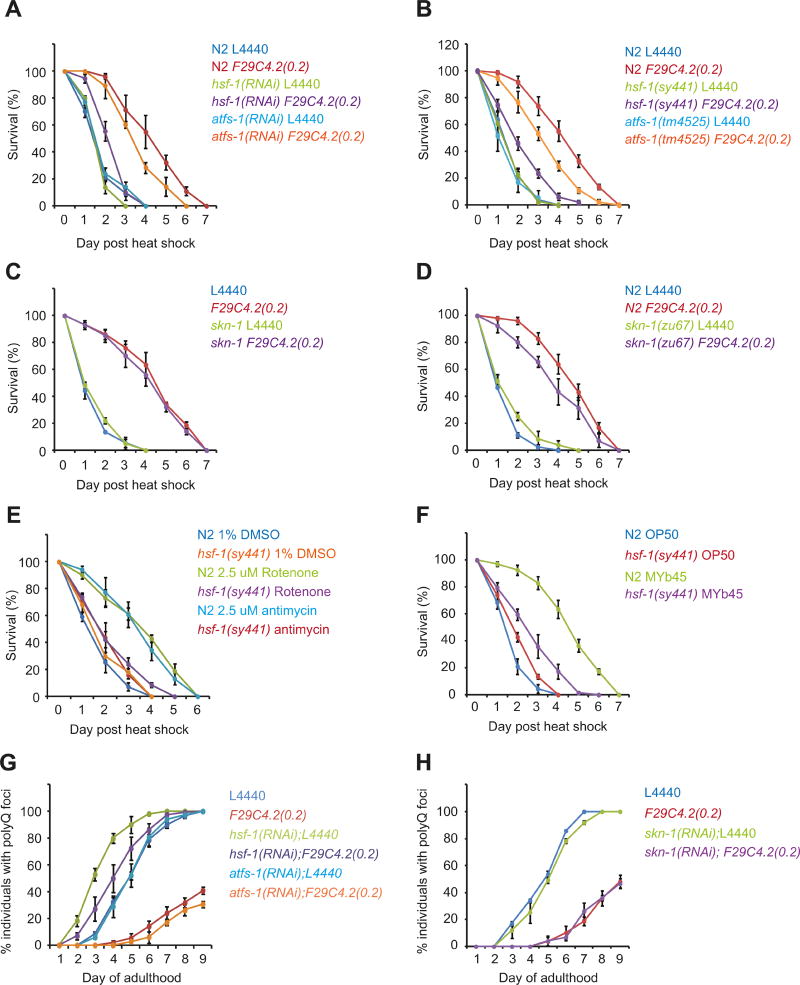

Mitochondrial perturbation is primarily associated with activation of the UPRmt and restoration of mitochondrial proteostasis. An important distinction shown here is that mitochondrial perturbation also maintains the HSR and cytosolic proteostasis with age. Given that the transcription factor HSF-1 is central to the HSR, stress resistance, and cytosolic proteostasis (Akerfelt et al., 2010; Li, Labbadia and Morimoto, 2017), we asked whether the beneficial effects of mitochondrial stress require HSF-1. Therefore, we examined survival following HS in animals exposed to L4440 or F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) in combination with hsf-1(RNAi) or atfs-1(RNAi), and in hsf-1(sy441) and atfs-1(tm4525) mutants that have a diminished HSR and UPRmt respectively (Bennett et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016; Nargund et al., 2015). Both RNAi mediated knock-down and loss of function mutations in hsf-1 and atfs-1 severely dampened the ability of F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) to induce stress response genes and fluorescent reporters associated with the HSR and UPRmt, thereby demonstrating that HSF-1 and ATFS-1 are essential for F29C4.2(0.2)RNAi to enhance the HSR and UPRmt respectively (Figure S5A-D).

Furthermore, while F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) significantly increased median survival following HS from 1.5 days to 4.1 days (Figure 5A), knockdown in the presence of either atfs-1(RNAi) or hsf-1(RNAi) reduced stress resistance by 25%, and 70% respectively (Figure 5A). Similarly, F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) mediated stress resistance was also decreased by 32% in atfs-1(tm4525) mutants and by 69% in hsf-1(sy441) mutants (Figure 5B), without affecting the efficacy of F29C4.2 knockdown (Figure S5E). Likewise, disruption of the oxidative stress response through RNAi or a loss-of-function mutation of the transcription factor SKN-1 ((skn-1(zu67)) had only modest effects on stress resistance in F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals (Figure 5C and D). Our data therefore suggest that atfs-1 and skn-1 contribute only modestly to stress resistance in F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) treated animals, and that mild ETC perturbation promotes stress resistance predominantly through hsf-1 and the HSR.

Figure 5. Mitochondrial perturbation enhances stress resistance and maintains proteostasis in an HSF-1 dependent manner.

(A-F) Survival following heat shock (35°C, 4h) on day 2 of adulthood.

(G and H) Proportion of Q44::YFP animals exhibiting intestinal polyglutamine aggregates at different days of adulthood.

Unless stated, all values are the mean of 4 biological replicates and bars denote SEM.

Consistent with our RNAi experiments, the enhanced stress resistance conferred by MYb45 or xenobiotics was also almost completely abolished in hsf-1(sy441) mutants, suggesting that animals prolong stress resistance in an HSF-1 dependent manner upon encountering mitochondrial stress inducing agents (Figure 5E and F).

Finally, we examined the relative roles of HSF-1 and ATFS-1 in the ability of mitochondrial perturbation to maintain cytosolic proteostasis with age. Strikingly, we found that atfs-1(RNAi) and skn-1(RNAi) essentially had no effect on the age-dependent aggregation of intestinal polyglutamine in the presence of L4440 or F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) (Figures 5G and H, and S5F). In contrast, hsf-1(RNAi) accelerated polyglutamine aggregation in L4440 animals and suppressed the maintenance of proteostasis in F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals by more than 5-fold (Figures 5G and S5F) suggesting that HSF-1 is integral to the ability of reduced ETC function to maintain cytosolic proteostasis and stress resistance.

Mild mitochondrial perturbation increases longevity and extends health-span in an HSF-1 dependent manner

HSF-1 activity is tightly coupled to lifespan, with reduced HSF-1 levels reported to significantly shorten lifespan in wild type, daf-2, age-1, and isp-1;ctb-1 animals (Hsu et al., 2003; Morley and Morimoto, 2004; Walter et al., 2011). However, hsf-1 also been shown to be dispensable for lifespan extension conferred by paraquat induced superoxide and in isp-1 mutants grown in the presence of FUdR (Hsu et al., 2003; Yang and Hekimi, 2010).

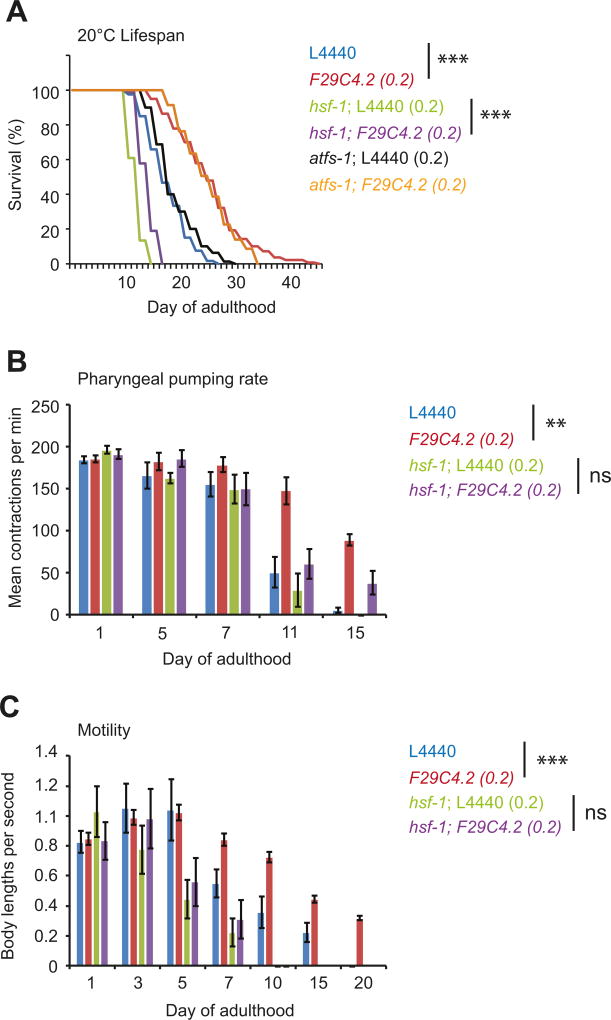

Given that HSF-1 is crucial for F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) to maintain proteostasis and stress resistance, we asked whether the ability of mild mitochondrial perturbation to override the repression of the HSR could also improve life- and health-span in an HSF-1 dependent manner. Mild mitochondrial perturbation through F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) increased both median and maximal lifespan by 50% (Figure 6A). However, increased lifespan through F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) was not dependent on atfs-1 (Figure 6A). In addition, F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) also maintained two well established markers of health-span; motility and pharyngeal pumping rate, at a more youthful state into adulthood (Figure 6B and C). In contrast, hsf-1(RNAi) reduced lifespan and prematurely impaired pharyngeal pumping and paralysis (Figure 6A - C). Consistent with the dependence on HSF-1 for the maintenance of proteostasis and stress resistance upon ETC perturbation, hsf-1(RNAi) significantly truncated life and health-span to almost wild type levels in F29C4.2(0.2)(RNAi) animals (Figure 6A - C).

Figure 6. Mitochondrial perturbation maintains somatic health in an HSF-1 dependent manner.

(A) Lifespan of wild type worms grown on L4440 (n = 120), F9C4.2(0.2) (n = 129), hsf-1;L4440(0.2) (n = 97), hsf-1;F29C4.2(0.2) (n = 88), atfs-1; L4440(0.2) (n = 120), or atfs-1; F29C4.2(0.2) (n = 103) RNAi at 20°C. Median lifespans were 18, 28, 14, 16, 19, and 29 days respectively. A second trial was also run which yielded highly similar results; L4440 (n = 81, 18 days), F9C4.2(0.2) (n = 82, 26 days), hsf-1;L4440(0.2) (n = 90, 14 days), hsf-1;F29C4.2(0.2) (n = 89, 16 days), atfs-1; L4440(0.2) (n = 80, 18 days), or atfs-1; F29C4.2(0.2) (n = 93, 28 days).

(B and C) Age-related changes in (B) pharyngeal pumping rate and (C) motility in wild type animals grown on L4440, F29C4.2(0.2), hsf-1;L4440(0.2), or hsf-1;F29C4.2(0.2) RNAi at 20°C. Values plotted are the mean of at least 20 animals. Bars denote SEM and statistical significance was calculated relative to respective L4440 controls by (A) Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and (B and C) two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Together, our data suggests that signaling through mitochondria can prevent the organismal repression of the HSR in early adulthood in order to preserve proteostasis and maintain somatic health under sub-optimal environmental conditions. This has profound effects on life and health-span and suggests that mitochondria are central regulators of the timing and severity of proteostasis collapse with age.

Discussion

The failure of proteostasis is a central feature of many age-related degenerative disorders, yet little is known regarding the factors that predispose cells to proteostasis collapse with age (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015b). Here we report that mitochondrial activity is a key determinant of the long-term activity of the HSR, proteostasis, and health-span in adulthood, and that low levels of mitochondrial stress are sufficient to maintain stress resistance and cytosolic proteostasis with age, in an hsf-1 dependent manner.

Reduced mitochondrial activity is associated with increased lifespan in C. elegans but typically comes at the cost of reduced fecundity and compromised health-span (Bansal et al., 2015; Rea et al., 2007; Wang and Hekimi, 2015), suggesting that increased lifespan through ETC perturbation comes at the expense of a poorer quality of life and compromised fitness. Furthermore, genetic interventions that prevent the age-related collapse of proteostasis are associated with reduced brood size or sterility (Shemesh et al., 2013; Labbadia et al., 2015a), suggesting that the maintenance of proteostasis in adulthood comes at a cost to reproductive capacity. Our studies have revealed that HSF-1 activity, stress resistance, cytosolic proteostasis, and health-span can all be maintained with age without causing reduced brood size, through exposure to mild mitochondrial stress.

Our proposal of a relationship between mitochondria and the integrity of the cytosolic proteome is not without precedent, as recent work has demonstrated a complex interplay between mitochondrial function and cytosolic proteostasis in yeast and C. elegans (Baker et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2016; Livnat-Levanon et al., 2014; Rainbolt et al., 2013; Ruan et al., 2017; Segref et al., 2014; Wang and Chen, 2015; Wrobel et al., 2015). Given that the vast majority of mitochondrial proteins are nuclear encoded and synthesized in the cytosol, it seems logical for cells to coordinate mitochondrial status with HSF-1 activity and cytosolic proteostasis. However, it had widely been accepted that changes in mitochondrial function do not alter HSF-1 activity, primarily because previous experiments were carried out early in life and/or solely in the context of mitochondrial stress (Yoneda et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2016). Our work challenges this view, and suggests that contrary to previous reports, relatively mild ETC disruption does influence the activity ofHSF-1 by over-riding the programmed repression of the HSR in early adulthood. Crucially, we show that this can provide long-term protection against proteotoxicity arising from the appearance of endogenous metastable proteins, or from the presence of chronically expressed disease associated polyglutamine proteins, suggesting that this pathway allows cells to mount a more effective response to any subsequent cytosolic protein misfolding that might occur as a consequence of age or environmental insults. Furthermore, our work suggests that changes in cytosolic proteostasis do not arise solely as a short-term survival adaptation to profound defects in mitochondrial protein import (Wrobel et al., 2015; Wang and Chen, 2015), but can also be triggered by subtle stresses or environmental cues to provide long-term organismal benefits.

Recently, changes in lipid biogenesis as a consequence of hsp-6 (mitochondrial HSP70) knockdown were shown to constitutively activate a mitochondrial/cytosolic stress response (McSR) through increased activity of ATFS-1 and HSF-1 (Kim et al., 2016). Our findings are distinct from these observations, as activation of the McSR does not occur from ETC perturbation and results in the constitutive induction of a sub-set of HSR genes when mitochondria are under severe duress (Kim et al., 2016). Our work suggests that a more nuanced relationship between mitochondrial stress and cytosolic protein quality control exists, and that this has a direct impact on the initiation of proteostasis collapse and ageing. Furthermore, our work implies that the sensing of protein folding stress can be transmitted across compartments in order to protect against subsequent stresses with age. As such, it will be crucial to understand to what extent, if at all, regulation of the age-related repression of the HSR is reliant on previously described modifiers of mitochondrial retrograde signaling.

An important question that arises from our work is whether maintenance of the HSR through mitochondrial stress is a physiologically relevant phenomenon. Our studies rule out the idea that maintenance of the HSR by mitochondrial perturbation is relevant only under circumstances where organismal health is challenged or crippled by extreme environmental adversity, as stress resistance, proteostasis, and healthspan can be maintained with minimal physiological disruption. Mitochondrial perturbation occurs naturally through imbalances in mitochondrial DNA, exposure to chemicals, and infection by bacterial pathogens (Gitschlag et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2014; Moullan et al., 2015; Pellegrino et al., 2014). We find that early life exposure to chemicals or microbes that can protract the reproductive period and lead to developmental delay in high doses, leads to the maintenance of stress resistance and cytosolic proteostasis in adulthood. This suggests that the ability to sense and adapt to potential threats to fitness before committing to reproduction could allow animals to delay egg-laying until more favorable conditions were found. Therefore, we propose that mitochondria can serve as “sentinels” to gauge fluctuations in the surrounding environment in order to influence the organismal “choice” to commit to programs that initiate reproduction at the cost of the soma, thereby preventing the repression of the HSR until animals find more favorable conditions in which to reproduce.

In summary, our findings provide a link between mitochondrial function, regulation of the HSR, and proteostasis, that may have important implications in our understanding of how different pathways converge to regulate rates of aging and fecundity. We propose that a greater understanding of the regulatory link between HSF-1 and mitochondrial function will be crucial as we attempt to uncover the drivers of proteostasis collapse in order to promote healthy aging.

Experimental procedures

Worm maintenance and strains

Worms were maintained using standard techniques as previously described (Brenner, 1974). All experiments were conducted at 20°C unless stated otherwise. Strains used in this study were wild type (N2), Bristol, MQ887 isp-1(qm150) IV, MQ1333 nuo-6(qm200) I, MQ130 clk-1(qm30) III, MQ989 isp-1(qm150) IV;ctb-1(qm89), TK22 mev-1(kn1)III, CW152 gas-1(fc21) X, NL1832 ucr-2.3(pk732) III, AM722 rmIs288[C12C8.1(hsp-70)p::mCherry; myo-2p::CFP], SJ4100 zcIs13[hsp-6p::GFP] V, EU1 skn-1(zu67) IV/nT1[unc-?(n754) let-? (IV;V), SJ4005 zcIs4[hsp-4p::GFP] V, CL2166 dvIs19[gst-4p::GFP::NLS] III, AM738 rmIs297[vha-6p::Q44::YFP; rol-6(su1006)], AM140 rmIs132[unc-54p::Q35::YFP], CB1301 unc-54(e1301ts) I, CB1402 unc-15(e1402ts) I, AM1061 unc-119(ed9)III, rmSi1[hsf-1p(4kb)::hsf-1(minigene)::gfp::3’UTR(hsf-1) + Cbrunc-119(+)] II; hsf-1(ok600) I, PS3551 hsf-1(sy441) I, TM4525 atfs-1(tm4525) V.

RNAi and creation of dilutions

RNAi was essentially performed as previously described (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003) with some modifications. NGM plates containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalatoside (IPTG, Sigma) were seeded with RNAi cultures. RNAi bacteria was grown in LB containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin at 37°C for 14 hours and then induced with 5 mM IPTG for a further 3 hours at 37°C with continuous shaking. RNAi dilutions were created by thoroughly mixing RNAi cultures at an OD600 of 1.5 – 1.6 with L4440 bacterial cultures at the same OD600. All RNAi clones used in this study were confirmed by sequencing.

Chemical treatment of worms and growth on alternate microbes

Antimycin A (sigma) or rotenone (sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and added to NGM plates to the desired concentration before pouring. Plates containing 1% DMSO (v/v) were used as controls. Plates were seeded with OP50 E. coli and allowed to dry thoroughly before use. Worms were synchronized to xenobiotic plates by egg-laying and allowed to develop until the late L4 stage before being transferred to control plates for heat shock at day 2 of adulthood. Chemical containing NGM plates were stored at 4°C until use and always used within 2 weeks of pouring. For culturing worms on Microbacterium MYb45, achromobacter MYb9, and stenotrophomonas MYb57, all bacterial lines were grown and seeded onto standard NGM plates and then allowed to dry for 3 days at room temperature. All microbial plates were used within 1 week of seeding.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

RNA extraction and real time quantitative PCR were performed as previously described (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a). Briefly, worms were lysed in 250 µl of Trizol (Invitrogen)vigorously shaken with chloroform, allowed to stand for 3 minutes at room temperature, and then centrifuged at 16,000g at 4°C. The aqueous phase was then collected and RNA was purified using Qiagen RNeasy min-elute columns and gDNA eliminator columns as per manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng RNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Biorad).RT-qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate for each gene using iQ SYBR green super mix (Biorad) using a Biorad iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system. Relative expression of genes was determined using the relative standard curve method. All primers used can be found in Table S1.

Thermorecovery assays

Thermorecovery assays were performed as previously described (Labbadia and Morimoto, 2015a) with the exception that lethal heat shock was measured as relative motility or survival following either a non-lethal heat shock (33°C, 6 hours) or a lethal heat shock (35°C, 4 hours) respectively. For non-lethal thermorecovery, 25–30 animals were picked onto new seeded plates, wrapped tightly with parafilm, and submerged in a water bath at 33°C for 6 hours. Following heat shock treatment, worms were allowed to recover for 48 hours at 20°C, after which, the proportion of the population moving normally in response to 3 plate taps was scored. Animals were scored as having abnormal movement if they exhibited paralysis, uncoordinated sinusoidal movement, sluggishness/lethargy (moving less than 1 body length per second) or irresponsiveness to plate tap. Lethal heat shock was conducted in the same manner but in a water bath at 35°C for 4 hours. Survival was then scored at 24 hour intervals following heat shock until the entire population was dead. Worms were scored as dead in the complete absence of touch response and pharyngeal pumping.

Fecundity assays

Worms were singled onto 3 cm plates seeded with bacteria on the first day of adulthood and allowed to lay eggs. Worms were then transferred to new plates every day throughout adulthood until egg-laying had ceased and plates containing eggs were incubated at 20°C for 48 hours, after which the number of progeny produced on each day of adulthood was counted. The mean number of progeny produced on each day of adulthood was calculated from 20 worms per treatment group.

Motility assays

Assessment of animal motility with age was conducted as previously described (Nussbaum-Krammer et al., 2015). Briefly, 30 – 40 age-synchronized worms were picked onto NGM plates with a thin bacterial lawn and allowed to acclimatize for 30 minutes. Worms were transferred to new plates to remove progeny. Plates were tapped 3 times to stimulate movement and motility was then recorded for 30 seconds. Motility videos were captured using a Leica stereomicroscope at 10X magnification with a Hamamatsu Orca-R2 digital camera C10600-10B and Hamamatsu Simple PCI imaging software.

Pharyngeal pumping assays

To score pumping rates with age, worms were transferred individually to new plates and pharyngeal pumping was counted for 6 independent periods of 10 seconds to obtain the number of contractions per minute. Pumping was scored for 20 worms per group and the average number of contractions per minute was then calculated for each population of worms.

Lifespan assays

Worms were allowed to reach adulthood and then scored for dead worms every other day throughout life. Animals were transferred to new plates every day for the first 7 days of adulthood and then transferred to new plates every 4 days thereafter. Worms were scored as dead in the absence of pharyngeal pumping and response to touch with a platinum pick.

Fluorescence microscopy

Worms were imaged by mounting on 5% agarose pads in 3 mM levamisole. Fluorescence and bright field images of reporter worms were acquired using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope, a Hamamatsu Orca 100 cooled CCD camera and Zeiss axiovision software. Images of intestinal and body wall muscle polyglutamine aggregates were captured using a Leica SP5 II laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with HyD detectors. Acquisition parameters were kept identical across samples.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was calculated by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test for lifespan assays. Either one-way ANOVA with Tukey post analysis pair wise comparison of groups, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post analysis correction, or two-tailed Student’s t-test were used for all other comparisons as stated in figure legends. Statistical tests used are declared in all figure legends and were calculated using GraphPad Prism (ANOVA, Log-rank) or Microsoft Excel (t-test).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilya Ruvinsky, Yoko Shibata, and Jian Li for critical reading of the manuscript, and the Keck Biophysics, High Throughput Analysis, and Biological Imaging Facilities at Northwestern University for equipment use. The anti-HSP-16 antibody was a kind gift from Gordon Lithgow and the anti-HSP-6 antibody was generated by Cindy Voisine. MYb bacterial strains were a kind gift from Hinrich Schulenburg. We also thank David Gems for the use of general equipment and reagents. Many of the strains used in this study were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). Strain TM4525 was provided by the National Bioresource Project (Tokyo, Japan). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging), the Ellison Medical Foundation, and the Daniel F. and Ada L. Rice Foundation to RIM (R37AG026647, P01 AG049665) and R01AG047182 to CMH, as well as a Milton Safenowitz Post-doctoral Fellowship and a BBSRC David Phillips Fellowship (BB/P005535/1) to JL.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

JL designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and constructed figures. RIM designed experiments and analyzed data. JL, RMB, and MFN performed genome-wide RNAi screening. Y-FL and CMH designed and performed oxygen consumption experiments. JL and RIM wrote the manuscript with input from Y-FL, CMH, RMB, and MFN.

References

- Akerfelt M, Morimoto RI, Sistonen L. Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2010;11:545–555. doi: 10.1038/nrm2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreux PA, Mouchiroud L, Wang X, Jovaisaite V, Mottis A, Bichet S, Moullan N, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J. A method to identify and validate mitochondrial modulators using mammalian cells and the worm C. elegans. Scientific reports. 2014;4:5285. doi: 10.1038/srep05285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BM, Nargund AM, Sun T, Haynes CM. Protective coupling of mitochondrial function and protein synthesis via the eIF2alpha kinase GCN-2. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, Zhu LJ, Yen K, Tissenbaum HA. Uncoupling lifespan and healthspan in Caenorhabditis elegans longevity mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E277–286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412192112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruah A, Chang H, Hall M, Yuan J, Gordon S, Johnson E, Shtessel LL, Yee C, Hekimi S, Derry WB, et al. CEP-1, the Caenorhabditis elegans p53 homolog, mediates opposing longevity outcomes in mitochondrial electron transport chain mutants. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zvi A, Miller EA, Morimoto RI. Collapse of proteostasis represents an early molecular event in Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14914–14919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902882106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CF, Vander Wende H, Simko M, Klum S, Barfield S, Choi H, Pineda VV, Kaeberlein M. Activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response does not predict longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature communications. 2014;5:3483. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David DC, Ollikainen N, Trinidad JC, Cary MP, Burlingame AL, Kenyon C. Widespread protein aggregation as an inherent part of aging in C. elegans. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A, Hsu AL, Arantes-Oliveira N, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Hsin H, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C. Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science. 2002;298:2398–2401. doi: 10.1126/science.1077780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen P, Marsh SA, Braker I, Heitland N, Wagner S, Nakad R, Mader S, Petersen C, Kowallik V, Rosenstiel P, Félix MA, Schulenburg H. The native microbiome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: gateway to a new host-microbiome model. BMC Biol. 2016;9:38. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0258-1. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bussiere F, Hekimi S. Mitochondrial electron transport is a key determinant of life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental cell. 2001;1:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitschlag BL, Kirby CS, Samuels DC, Gangula RD, Mallal SA, Patel MR. Homeostatic Responses Regulate Selfish Mitochondrial Genome Dynamics in C. elegans. Cell metabolism. 2016;24:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CM, Yang Y, Blais SP, Neubert TA, Ron D. The matrix peptide exporter HAF-1 signals a mitochondrial UPR by activating the transcription factor ZC376.7 in C. elegans. Molecular cell. 2010;37:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtkooper RH, Mouchiroud L, Ryu D, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Knott G, Williams RW, Auwerx J. Mitonuclear protein imbalance as a conserved longevity mechanism. Nature. 2013;497:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nature12188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AL, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300:1142–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1083701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30:313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HE, Grant AR, Simic MS, Kohnz RA, Nomura DK, Durieux J, Riera CE, Sanchez M, Kapernick E, Wolff S, et al. Lipid Biosynthesis Coordinates a Mitochondrial-to-Cytosolic Stress Response. cell. 2016;166:1539–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.027. e1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Sun H. Functional genomic approach to identify novel genes involved in the regulation of oxidative stress resistance and animal lifespan. Aging cell. 2007;6:489–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. Proteostasis and longevity: when does aging really begin? F1000prime reports. 2014;6:7. doi: 10.12703/P6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. Repression of the Heat Shock Response Is a Programmed Event at the Onset of Reproduction. Molecular cell. 2015a;59:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annual review of biochemistry. 2015b;84:435–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. Determination of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by four clock genes. Science. 1996;272:1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Lee RY, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Ruvkun G. A systematic RNAi screen identifies a critical role for mitochondria in C. elegans longevity. Nature genetics. 2003;33:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chauve L, Phelps G, Brielmann RM, Morimoto RI. E2F coregulates an essential HSF developmental program that is distinct from the heat-shock response. Genes & development. 2016;30:2062–2075. doi: 10.1101/gad.283317.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. Rethinking HSF1 in stress, development, and organismal health. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;17:30139–30150. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YF, Schulz AM, Pellegrino MW, Lu Y, Shaham S, Haynes CM. Maintenance and propagation of a deleterious mitochondrial genome by the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Nature. 2016;533:416–419. doi: 10.1038/nature17989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Samuel BS, Breen PC, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans pathways that surveil and defend mitochondria. Nature. 2014;508:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature13204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livnat-Levanon N, Kevei E, Kleifeld O, Krutauz D, Segref A, Rinaldi T, Erpapazoglou Z, Cohen M, Reis N, Hoppe T, et al. Reversible 26S proteasome disassembly upon mitochondrial stress. Cell reports. 2014;7:1371–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri-Shiomi A, Garsin DA. Insulin signaling and the heat shock response modulate protein homeostasis in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine during infection. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:194–201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JF, Morimoto RI. Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Molecular biology of the cell. 2004;15:657–664. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullan N, Mouchiroud L, Wang X, Ryu D, Williams EG, Mottis A, Jovaisaite V, Frochaux MV, Quiros PM, Deplancke B, et al. Tetracyclines Disturb Mitochondrial Function across Eukaryotic Models: A Call for Caution in Biomedical Research. Cell reports. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund AM, Fiorese CJ, Pellegrino MW, Deng P, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial and nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor ATFS-1 promotes OXPHOS recovery during the UPR(mt) Molecular cell. 2015;58:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science. 2012;337:587–590. doi: 10.1126/science.1223560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum-Krammer CI, Neto MF, Brielmann RM, Pedersen JS, Morimoto RI. Investigating the spreading and toxicity of prion-like proteins using the metazoan model organism C. elegans. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2015:52321. doi: 10.3791/52321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino MW, Nargund AM, Kirienko NV, Gillis R, Fiorese CJ, Haynes CM. Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature. 2014;516:414–417. doi: 10.1038/nature13818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V, Morimoto RI. Neuronal circuitry regulates the response of Caenorhabditis elegans to misfolded proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:14204–14209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106557108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainbolt TK, Atanassova N, Genereux JC, Wiseman RL. Stress-regulated translational attenuation adapts mitochondrial protein import through Tim17A degradation. Cell metabolism. 2013;18:908–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea SL, Ventura N, Johnson TE. Relationship between mitochondrial electron transport chain dysfunction, development, and life extension in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Rodrigues P, Czerwieniec G, Peters TW, Evani US, Alavez S, Gaman EA, Vantipalli M, Mooney SD, Gibson BW, Lithgow GJ, et al. Proteomic analysis of age-dependent changes in protein solubility identifies genes that modulate lifespan. Aging cell. 2012;11:120–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Snoek LB, De Bono M, Kammenga JE. Worms under stress: C. elegans stress response and its relevance to complex human disease and aging. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2013;29:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan L, Zhou C, Jin E, Kucharavy A, Zhang Y, Wen Z, Florens L, Li R. Cytosolic proteostasis through importing of misfolded proteins into mitochondria. Nature. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nature21695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar CE, Dues DJ, Spielbauer KK, Machiela E, Cooper JF, Senchuk M, Hekimi S, Van Raamsdonk JM. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS have opposing effects on lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segref A, Kevei E, Pokrzywa W, Schmeisser K, Mansfeld J, Livnat-Levanon N, Ensenauer R, Glickman MH, Ristow M, Hoppe T. Pathogenesis of human mitochondrial diseases is modulated by reduced activity of the ubiquitin/proteasome system. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh N, Shai N, Ben-Zvi A. Germline stem cell arrest inhibits the collapse of somatic proteostasis early in Caenorhabditis elegans adulthood. Aging cell. 2013;12:814–822. doi: 10.1111/acel.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MC, Fox S, Beam M, Thakkar H, Amaral MD, Morimoto RI. A genetic screening strategy identifies novel regulators of the proteostasis network. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RC, Dillin A. XBP-1 is a cell-nonautonomous regulator of stress resistance and longevity. cell. 2013;153:1435–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter L, Baruah A, Chang HW, Pace HM, Lee SS. The homeobox protein CEH-23 mediates prolonged longevity in response to impaired mitochondrial electron transport chain in C. elegans. PLoS biology. 2011;9:e1001084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther DM, Kasturi P, Zheng M, Pinkert S, Vecchi G, Ciryam P, Morimoto RI, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M, Mann M, et al. Widespread Proteome Remodeling and Aggregation in Aging C. elegans. cell. 2015;161:919–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen XJ. A cytosolic network suppressing mitochondria-mediated proteostatic stress and cell death. Nature. 2015;524:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Hekimi S. Mitochondrial dysfunction and longevity in animals: Untangling the knot. Science. 2015;350:1204–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel L, Topf U, Bragoszewski P, Wiese S, Sztolsztener ME, Oeljeklaus S, Varabyova A, Lirski M, Chroscicki P, Mroczek S, et al. Mistargeted mitochondrial proteins activate a proteostatic response in the cytosol. Nature. 2015;524:485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature14951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Hekimi S. A mitochondrial superoxide signal triggers increased longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda T, Benedetti C, Urano F, Clark SG, Harding HP, Ron D. Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. Journal of cell Science. 2004;117:4055–4066. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun J, Finkel T. Mitohormesis. Cell metabolism. 2014;19:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.