Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) for the prevention of laboratory-confirmed influenza and influenza-like illnesses (ILI) among children and adolescents receiving therapy for acute leukemia (AL).

Study design

A retrospective review of the demographic and clinical characteristics of 498 patients at a pediatric cancer center who received therapy for acute leukemia during 3 successive influenza seasons (2010–11 through 2012–13).

Results

In 498 patient seasons with known immunization history (patients’ median age 6 yrs, range 1–21 yrs), 354 (71.1%) patients were immunized with TIV and 98 (19.7%) received a booster dose of vaccine. Vaccinated and unvaccinated patients had generally similar demographic characteristics. There were no significant differences in the overall rates of influenza or ILI between vaccinated and unvaccinated patients overall, or in any individual season. There was no significant difference in the rates of influenza or ILI between patients who received one dose of vaccine and those who received two doses. Time to first influenza infection and time to first ILI in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients were not statistically significantly different.

Conclusion

TIV did not protect children and adolescents with AL against laboratory-confirmed influenza or ILI. Future prospective studies should assess TIV effectiveness in high-risk subpopulations and alternative strategies to prevent influenza should be considered in this population.

Keywords: pediatric, cancer, leukemia, immunization, prevention, respiratory infection

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend all persons 6 months of age and older receive annual seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine, noting that special efforts should be made to vaccinate children who are immunocompromised or who have chronic illnesses, as these patients are at greater risk for complications from influenza than otherwise healthy children.1–3 Children receiving treatment for cancer have a less robust response to influenza vaccination than do healthy children, but 38–100% develop immune responses considered to correlate with protection from infection and reported adverse effects associated with these vaccines are generally mild and self-limited.4, 5 Thus, even a small benefit of vaccine has the potential to outweigh risks associated with vaccination. Two systematic reviews conducted in 2013 and 2014, however, concluded that it was uncertain whether or not the immune response to trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) protects pediatric or adult oncology patients from influenza or its complications.4, 6 The only study to address this question since the publication of these analyses suggested an overall benefit to pediatric oncology patients, but unclear effectiveness in children with hematologic malignancies.7 We therefore reviewed the vaccination history and clinical course of patients receiving treatment for AL at a pediatric cancer center over three successive influenza seasons. The objectives of this study were to determine the effectiveness of TIV in preventing laboratory confirmed influenza and the influenza-like illnesses (ILI) in patients with AL.

Methods

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude) provides comprehensive care to approximately 6,000 children with cancer and other immunocompromising conditions annually in Memphis, TN, and at a network of 8 domestic affiliates in the United States. Most of these children and adolescents live within the St. Jude catchment area. Children residing near affiliate clinics are referred to St. Jude for enrollment and initial treatment, then may return to the affiliate center for ongoing care closer to home, depending on the intensity of treatment and local resources. Information obtained during all patients’ health care encounters at St. Jude and its affiliates is maintained in a centralized electronic health record (EHR). Records of patient visits to providers who are not affiliated with St. Jude are also collected. Demographic and clinical characteristics, including respiratory infections and any solicited or unsolicited adverse effects of TIV vaccine, of patients who were undergoing active treatment for AL during 3 successive influenza seasons (2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14) were identified by retrospective review of EHR. Yearly influenza seasons were defined as the dates of the first through the last reported cases of influenza in Shelby County, TN, which, in most cases, were inclusive of the dates of reported influenza cases in the counties where affiliates are located. Most influenza infections were confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays or, less commonly, by rapid influenza antigen detection. ILI were defined using World Health Organization criteria as acute respiratory infections with a measured fever ≥38°C, cough, and onset within the preceding 10 days.8

Statistical analyses

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics and rates of disease were summarized by descriptive statistics. Treatment intensity was stratified as described by Kotecha.7 Overall rates of disease (laboratory-confirmed influenza, the primary endpoint, and ILI, the secondary endpoint) were computed as the total number of cases divided by the total days at risk of infection. Demographic characteristics were compared across influenza season and vaccination status using the Wilcoxon rank sum or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The Fisher exact test was used to assess differences in the type of circulating influenza virus across influenza seasons.

In assessing vaccine effectiveness, we assumed: 1) all patients were equally susceptible to influenza, 2) protective antibody responses were present 14 days after administration of TIV, 3) vaccine did not protect against influenza infection in a subsequent influenza season, and 4) that unvaccinated patients remained susceptible to influenza after infection (because multiple types of influenza circulated in each season). Patients were, therefore considered “immune” 14 days post-vaccination, and individuals could, depending on the date they received vaccine, contribute patient-days to both immune and susceptible groups. Rates of disease in immune and susceptible patients were computed as the total number of cases divided by the number of days immune and days susceptible, respectively. Poisson regression was used to compare rates of disease by vaccination status and number of doses of vaccine received. Time to infection was defined as the time between the first day of the influenza season (or cancer therapy, whichever occurred later) and the date of symptom onset; for patients without infections, time to disease was censored at the last day of the influenza season (or completion of cancer therapy, whichever occurred earlier). Kaplan-Meier methods were used to produce time to disease estimates. The log rank test was used to examine differences in time to first occurrence of disease (influenza or ILI) between susceptible and immune patients within each influenza season and across all influenza seasons.

Logistic regression was used to examine the individual effects of age, sex, treatment intensity, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), and lymphopenia on the risk of infection among immunized patients. Logistic regression and time to event analyses were conducted under the assumption that patients followed across multiple seasons were independent and multiple infections within the same patient were independent. All analyses were confined to the subset of patients with available vaccination history. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. All statistical tests were 2-sided and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There were a total of 574 patient influenza seasons; vaccination history was known for 498 (86.8%) patient seasons. Most patients with uncertain vaccination status had leukemia diagnosed during the influenza season and lacked documentation of vaccines recently provided by their personal physicians. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient population with available vaccination history are summarized in Table I. Most patients (94% overall) had acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); 93% of these were treated on the TOTALXVI protocol. Patients’ age, sex, underlying malignancies, treatment intensity, absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC), and the proportion of patients with mild/moderate or severe lymphopenia were similar across influenza seasons. Most patients (70%) were lymphopenic.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of acute leukemia patients with available vaccination history

| Characteristics | Overall | 2010–11 Season | 2011–12 Season | 2012–13 Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 574 | 182 | 205 | 187 |

| Total no. of patients with vaccination history | 498 (86.8%) | 151 (83%) | 180 (87.8%) | 167 (89.3%) |

| Age in years, Median (range) | 6 (1–21) | 6 (1–20) | 6 (1–20) | 6 (1–21) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 206 (41.4%) | 66 (43.7%) | 76 (42.2%) | 64 (38.3%) |

| Male | 292 (58.6%) | 85 (56.3%) | 104 (57.8%) | 103 (61.7%) |

| Underlying malignancy | ||||

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 468 (94%) | 146 (96.7%) | 165 (91.7%) | 157 (94%) |

| Acute myeloblastic leukemia | 24 (4.8%) | 3 (2%) | 12 (6.7%) | 9 (5.4%) |

| Acute mixed lineage leukemia | 6 (1.2%) | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (1.7%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Treatment intensity based on chemotherapy phase | ||||

| High | 71 (14.3%) | 16 (10.6%) | 28 (15.6%) | 27 (16.2%) |

| Low | 427 (85.7%) | 135 (89.4%) | 152 (84.4%) | 140 (83.8%) |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC,/mm3), at time of vaccination | ||||

| Median (range) | 740 (21–4,005) | 786.5 (21–3,526) | 736 (140–4,005) | 698 (100–3,600) |

| Normal (≥1000) | 104 (20.9%) | 31 (20.5%) | 39 (21.7%) | 34 (20.4%) |

| Mild/moderate lymphopenia (501–999) | 159 (31.9%) | 55 (36.4%) | 47 (26.1%) | 57 (34.1%) |

| Severe lymphopenia (≤500) | 84 (16.9%) | 18 (11.9%) | 29 (16.1%) | 37 (22.2%) |

| Unknown | 151 (30.3%) | 47 (31.1%) | 65 (36.1%) | 39 (23.4%) |

Abbreviations: ALC – absolute lymphocyte count

In 498 patient seasons with known immunization history, 354 (71.1%) patients were vaccinated and 98 (19.7%) received a booster dose of vaccine at a median interval of 35 days (Table 2). Vaccinated and unvaccinated patients had similar demographic characteristics except that, overall, a greater proportion of patients who were vaccinated had ALL (95.5% vs. 90.3%, p=0.034) and, overall and across all seasons, vaccinated patients were more likely to be in a low intensity phase of cancer therapy (90.7% vs. 73.6% overall, p<0.0001) than unimmunized patients. There was no significant association observed between vaccination status or number of doses of vaccine received and risk of developing influenza or ILI. Specifically, there was no significant difference in the overall rates of influenza between immune and susceptible patients, overall (0.73 vs 0.70, p=0.874), or in any individual season (2010–11, 0.86 vs. 0.57, p=0.465; 2011–12, 0.35 vs. 0.29, p=0.784; 2012–13, 1.10 vs. 1.62, p=0.342) (Table 2). There was also no significant difference in the rates of ILI between immune and susceptible patients, overall (2.44 vs. 2.41, p=0.932), or in any individual season (2010–11, 2.92 vs. 2.70, p=0.775; 2011–12, 2.27 vs. 2.34, p=0.907; 2012–13, 2.20 vs. 2.16, p=0.967).

Table 2.

Summary of influenza and influenza-like illnesses by season

| Overall | 2010–11 Season | 2011–12 Season | 2012–13 Season | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza vaccination | ||||

| Total no. of patients | 498 | 151 | 180 | 167 |

| Received vaccination | 354 (71.1%) | 104 (68.9%) | 120 (66.7%) | 130 (77.8%) |

| Received booster dose of vaccine* | 98 (27.7%) | 27 (26.0%) | 20 (16.7%) | 51 (39.2%) |

| Days between primary and booster vaccinations, Median (range) | 35 (21–136) | 28 (27–48) | 42 (27–91) | 35 (21–136) |

| Influenza | ||||

| Episodes of influenza | 53 | 17 | 10 | 26 |

| Overall rate of influenza† | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.33 | 1.24 |

| Episodes of influenza in vaccinated immune patients | 37 | 13 | 7 | 17 |

| Rate of influenza in vaccinated immune patients† | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 1.10 |

| Episodes of influenza in unvaccinated susceptible patients | 16 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Rate of influenza in unvaccinated susceptible patients† | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 1.62 |

| Influenza-like Illnesses (ILI) | ||||

| Episodes of ILI | 178 | 63 | 69 | 46 |

| Overall rate of ILI† | 2.43 | 2.85 | 2.30 | 2.19 |

| Episodes of ILI in vaccinated immune patients | 123 | 44 | 45 | 34 |

| Rate of ILI in immune patients† | 2.44 | 2.92 | 2.27 | 2.20 |

| Episodes of ILI in susceptible patients | 55 | 19 | 24 | 12 |

| Rate of ILI in susceptible patients† | 2.41 | 2.70 | 2.34 | 2.16 |

Number and proportion of patients who received a first dose of vaccine

Cases per 1,000 patient days

The rates of influenza and ILI in vaccinated patients receiving one or two doses of vaccine are summarized for each influenza season and across all seasons in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the rates of influenza between patients who received one dose and those who received two doses, overall (0.60 vs. 1.02, p=0.107), or in any individual season (2010–11, 0.60 vs. 1.53, p=0.094; 2011–12, 0.29 vs. 0.53, p=0.478; 2012–13, 1.14 vs. 1.01, p=0.798). Of patients who received 2 doses, influenza occurred after receiving both doses of vaccine. There was also no significant difference in the rates of ILI between patients who received one dose and those who received two doses, overall (2.42 vs. 2.73, p=0.529), or in any individual season (2010–11, 3.10 vs. 2.29, p=0.420; 2011–12, 2.10 vs. 3.17, p=0.218; 2012–13, 2.17 vs. 2.73, p=0.471).

Table 3.

Summary of influenza and influenza-like illnesses by season and number of vaccinations

| Overall | 2010–11 Season | 2011–12 Season | 2012–13 Season | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 dose | 2 doses | 1 dose | 2 doses | 1 dose | 2 doses | 1 dose | 2 doses | |

| Total no. of patients | 256 | 98 | 77 | 27 | 100 | 20 | 79 | 51 |

| Influenza | ||||||||

| Episodes of influenza | 23 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 7 |

| Rate of influenza* | 0.60 | 1.02 | 0.60 | 1.53 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 1.14 | 1.01 |

| Influenza-like Illnesses (ILI) | ||||||||

| Episodes of ILI | 93 | 40 | 36 | 9 | 36 | 12 | 21 | 19 |

| Rate of ILI* | 2.42 | 2.73 | 3.10 | 2.29 | 2.10 | 3.17 | 2.17 | 2.73 |

Per 1,000 patient days

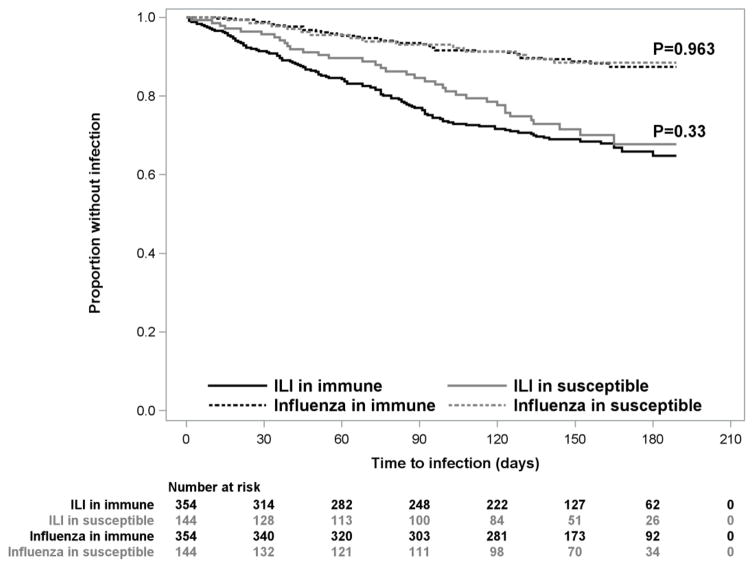

Time to first influenza infection and time to first ILI in immune and susceptible patients are shown in the Figure. There were no statistically significant differences observed for days to first episode of influenza (p=0.963) or days to first episode of ILI (p=0.330) between immune and susceptible patients in any individual season or across all influenza seasons.

Figure. Time to first occurrence of influenza and ILI in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

There were no statistically significant differences observed for days to first episode of influenza (p=0.963) or days to first episode of ILI (p=0.330) between immune and susceptible patients across all influenza seasons. Also, there were no statistically significant differences observed for days to first episode of influenza or days to first episode of ILI between immune and susceptible patients during individual influenza seasons (data not shown).

There was no significant association observed between demographic and clinical factors and developing influenza. Across all influenza seasons, both age and ALC were significantly associated with development of ILI. A 1-year increase in age was associated with a reduced odds of developing ILI (OR 0.920, 95% CI 0.881–0.960; p<0.001). ALC was not documented for a substantial number of patients; thus the following results are based on a subset of available data. When analyzed as a continuous variable, a 100-unit increase in ALC was associated with a slightly increased risk of ILI (OR 1.054, 95% CI 1.015–1.095; p=0.006). Patients with a mild/moderate degree of lymphopenia had a significantly reduced odds of developing ILI compared with patients with normal values (OR 0.523, 95% CI 0.318–0.860; p=0.011); patients with severe lymphopenia also had a reduced, but not statistically significantly reduced, risk of ILI (OR 0.627, 95% CI 0.354–1.109; p=0.109).

Influenza types and serotypes causing infections are summarized in Table 4 (available at www.jpeds.com). There was a larger proportion of infectious caused by influenza B viruses during the 2010–11 season compared with the 2011–12 and 2012–13 seasons [60% (n=15), 22% (n=9), and 33% (n=24), respectively; p=0.034]. No serious adverse effects of immunization were noted in any vaccinated patient.

Table 4.

Summary of influenza types and subtypes causing infections, by season

| Overall | 2010–11 Season | 2011–12 Season | 2012–13 Season | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of episodes of influenza | 53 | 17 | 10 | 26 | |

| Type A | All A | 29 (54.7%) | 6 (35.3%) | 7 (70%) | 16 (61.5%) |

| Not subtyped | 16 (30.2%) | 4 (23.5%) | 4 (40%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| A H3N1 | 11 (20.8%) | 0 | 3 (30%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| A H1N1 | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (11.8%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Type B | 19 (35.8%) | 9 (52.9%) | 2 (20%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| Unknown* | 5 (9.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (7.7%) |

Testing method did not distinguish between type A and type B viruses.

Discussion

The estimated adjusted vaccine effectiveness of TIV vaccines in healthy children in the 2010–2011 through 2012–2013 season ranges from 24–71%, suggesting at least modest effectiveness in healthy children.9–11 This study finds, however, that TIV provided no protection against laboratory-confirmed influenza or ILI for children and adolescents receiving therapy for AL. In another study assessing the effectiveness of TIV in this population. Kotecha et al followed 100 Australian pediatric oncology patients (<18 yrs of age) with a variety of oncologic diagnoses across 2 influenza seasons.7 Although these authors did not describe outcomes of children with AL separately, their results appear consistent with those of the current study. Children with hematologic malignancies were significantly less likely to seroconvert or achieve seroprotection following vaccination than those with solid tumors, and most children with laboratory-confirmed influenza (11 of 13) had hematologic malignancies, including the only 2 children in the vaccinated study population who developed influenza. Choi et al also found similar rates of influenza and ILI among pediatric oncology patients who responded to TIV with an HAI titer of >1:40 and/or a 4-fold increase in HAI titers and sero-nonresponders.12

There are several possible explanations for poor vaccine efficacy in children with AL. Immunity provided by influenza vaccine generally is strain-specific and, during some seasons, antigenic drift or changes in the predominant lineage among circulating viruses might result in mismatches between circulating strains and those included in the vaccine. In all three seasons, influenza A was the predominant circulating virus (70–82%). The proportion of influenza A (H3N2) viruses increased from 62% to 94% over the 3 seasons, and that of 2009 influenza A (H1N1) viruses decreased correspondingly. In the 2010–11 and 2012–13 seasons ≥ 96% of circulating influenza A (H3N2) viruses characterized by the CDC were antigenically similar to that year’s vaccine component, compared with 75% in the 2011–12 season. In all seasons, ≥96% of characterized influenza A (H1N1) viruses were similar to the H1N1 component of the Northern Hemisphere vaccine for that year. Influenza B vaccine components were only well matched to circulating viruses in the 2010–11 season.13–15 Fewer cases of influenza were identified in this study in the 2011–12 influenza season than in other years, and only in the 2010–11 season was a disproportionate proportion of infections caused by influenza B viruses in this study. Therefore, no advantage to vaccination was observed in seasons when vaccine was well matched to circulating viruses. Although the relative proportion of each virus type and subtype can vary across geographic regions and over time, this suggests that a mismatch between circulating viruses and vaccine composition is not the most important cause of poor vaccine effectiveness in children with AL.13

Vaccinated patients in this study were not at increased risk of influenza infection with increasing time from vaccination, and administration of a booster dose of vaccine did not increase vaccine effectiveness significantly, suggesting that a shortened duration of protective immunity relative to healthy persons also was not primarily responsible for the vaccine’s poor protective efficacy. There are considerable data, however, which suggest that the currently recognized serological correlate of protection may not be appropriate for children with AL. Although a hemagglutination inhibition antibody (HAI) titer of 1:32 or 1:40 correlates with approximately 50% protection against influenza in adults, a similar immune correlate has not been established in children.16 Kempe et al reported that a pre-influenza season HAI titer of ≥1:32 did not completely protect children with cancer from infection, suggesting that a higher serum antibody concentration may be required to correlate with protection in this population.17 Some models predict a progressive increase in protection with increasing HAI titers in healthy adults and children. 18–20 The role of qualitative differences in anti-influenza antibody and cell-mediated immune responses in immunity to influenza also are not yet understood well.21, 22 Although the majority of patients in this study were vaccinated during low intensity phases of chemotherapy, most children receiving therapy for leukemia have abnormal humoral immune responses and progressive decreases in cellular immunity over the course of cancer treatment. 23, 24 Studies of the immunogenicity of TIV in pediatric oncology patients suggest that both the degree of myelosuppression and the overall duration of immunosuppressive therapy may contribute to patients’ ability to generate effective immune responses.25, 26 Host-related factors, including age and the presence of other chronic medical disorders also can compromise the effectiveness of influenza vaccine, but the influence of these factors has not been studied in children with AL.27

Previous studies have identified factors predicting lower rates of seroconversion to TIV, but have not examined risk factors for influenza and ILI.3, 7, 28, 29 Younger patients in the current study, and those with higher lymphocyte counts were more likely to develop ILI, but not laboratory-confirmed influenza. Assuming that vaccine does not protect against influenza in this population, these associations may reflect intrinsic infection characteristics (e.g. higher rates of respiratory tract infections in younger children), or behavioral characteristics (e.g. voluntary limitation of social activities when neutropenic or lymphopenic). Additional studies addressing these possibilities are warranted because these risk factors, particularly differences in behaviors, may be modifiable.

Strengths of this study include the inclusion and systematic follow up of all patients with known vaccination histories, and the use of both specific (laboratory-confirmed influenza) and less-specific (ILI) outcomes. This observational study, however, is subject to greater bias than a prospective cohort design. We were unable to control for the effects of the receipt of any influenza vaccine in preceding seasons, differences in exposure to infection (healthcare-associated or in the community), or oncologists’ prescribing habits with respect to influenza vaccine (such as their likelihood of recommending vaccinations to patients perceived as more or less ill, at risk of infection, or likely to respond to vaccine). Some differences in vaccination groups among subpopulations in the study, however, were likely to favor vaccinated children (eg, a higher proportion of vaccinees were in low intensity phases of therapy) and it seems unlikely, based on the current data and previous observations, that TIV has clinically significant protective efficacy in children with AL. These data cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other patient populations or centers. Children receiving therapy for solid tumors, for example, are more likely to seroconvert in response to influenza vaccination and may be more likely to benefit from vaccination.7 Likewise, the majority of patients included in this study were treated at a single center on a single protocol, TOTAL XVI - other treatment regimens might have greater or lesser impact on host immunity and the effectiveness of TIV. We did not assess illness characteristics in this study, and cannot exclude the fact that TIV, although not protective against infection, modified the severity of illness in vaccinated children. A previous review of the clinical characteristics of seasonal influenza in St. Jude patients, however, found that TIV was not associated with hospitalization for influenza, radiographically confirmed pneumonia, or serious complications. 30

Public health authorities and professional associations recommend that immunocompromised children, including those receiving cancer therapy, receive seasonal influenza vaccine annually. 1, 2 Increasing influenza vaccine coverage in pediatric oncology patients has even been the object of quality improvement projects. 31 Our data, however, suggest that influenza vaccine may be ineffective in children receiving therapy for AL and that routine administration of TIV may not reflect high value care. Further prospective studies formally assessing influenza vaccine effectiveness in pediatric oncology patients are warranted to potentially identify subgroups who may benefit from vaccination.

TIV effectiveness is not optimal, even in healthy children. Until more immunogenic and protective vaccines are developed, efforts to prevent influenza in high-risk populations should focus on more general strategies, such as avoiding ill persons and practicing good respiratory hygiene in households and healthcare facilities. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of other measures to prevent influenza, like the effectiveness of immunization, are largely unproven. Cocooning, the practice of vaccinating close contacts to prevent the spread of infection to individuals who themselves cannot be protected by vaccination, has had some success in protecting young infants against pertussis.32 The usefulness and cost effectiveness of cocooning to prevent influenza, however, have not been evaluated. Although annual influenza vaccination of healthcare providers is widely recommended and, in some settings, mandated, the impact of this activity on patients’ acquisition of infection has not been studied. Some recent studies even suggest that, depending on the genetic makeup of circulating strains, annual serial influenza immunization may negatively influence vaccine effectiveness and increase the risk of influenza in highly vaccinated populations.33, 34 Guidelines recommend consideration of pre-or post-exposure prophylaxis with oseltamivir and zanamivir for immunocompromised patients.1 There is some anecdotal experience in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients supporting the effectiveness and safety of this approach, and a recent meta-analysis suggested that these drugs are, overall, effective for prophylaxis of healthy individuals and households against seasonal and pandemic influenza.35, 36 A systemic review of published clinical trials, however, concluded that, although there was evidence of effect of neuraminidase inhibitors for post-exposure prophylaxis of influenza in healthy children, effect was modest, with a number needed to treat of 13.37

The disappointing results of this study highlight the urgent need for further research in this field, including work to identify the immunological correlates of protection for influenza vaccines in children, formal evaluations of the effectiveness of strategies to prevent influenza in children and adolescents with cancer, and the development of novel vaccines with more broadly cross-reactive epitopes and/or adjuvants capable of increasing the amplitude and duration of immune responses to relevant antigens.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA21765) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

We thank Drs Hana Hakim and Richard Webby for their critical review of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Abbreviations

- AL

acute leukemia

- ALC

absolute lymphocyte count

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- EHR

electronic health record

- HAI

hemagglutinin inhibition titer

- ILI

influenza-like illness

- TIV

trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee. Pediatrics. 2016. On Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2016–2017; p. 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Olsen SJ, Karron RA, Jernigan DB, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–54. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6505a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisholm JC, Devine T, Charlett A, Pinkerton CR, Zambon M. Response to influenza immunisation during treatment for cancer. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:496–500. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.6.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goossen GM, Kremer LC, van de Wetering MD. Influenza vaccination in children being treated with chemotherapy for cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD006484. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006484.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakim H, Allison KJ, Van de Velde LA, Tang L, Sun Y, Flynn PM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of high-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine compared to standard-dose vaccine in children and young adults with cancer or HIV infection. Vaccine. 2016;34:3141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shehata MA, Karim NA. Influenza vaccination in cancer patients undergoing systemic therapy. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2014;8:57–64. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S13774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotecha RS, Wadia UD, Jacoby P, Ryan AL, Blyth CC, Keil AD, et al. Immunogenicity and clinical effectiveness of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in immunocompromised children undergoing treatment for cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:285–93. doi: 10.1002/cam4.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Association. Global Epidemiological Surveillance Standards for Influenza. Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Available at: http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/WHO_Epidemiological_Influenza_Surveillance_Standards_2014.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME, Kieke BA, Gaglani M, Murthy K, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012–2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:1529–40. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohmit SE, Thompson MG, Petrie JG, Thaker SN, Jackson ML, Belongia EA, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2011–2012 season: protection against each circulating virus and the effect of prior vaccination on estimates. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:319–27. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treanor JJ, Talbot HK, Ohmit SE, Coleman LA, Thompson MG, Cheng PY, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccines in the United States during a season with circulation of all three vaccine strains. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:951–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KC, Fuleihan RL, Walterhouse DO. Serologic response and clinical efficacy of influenza vaccination in children and young adults on chemotherapy for cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:2011–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity--United States, 2010–11 season, and composition of the 2011–12 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity - United States, 2011–12 season and composition of the 2012–13 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012–2013 Influenza season surveillance summary. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullers JA, Huber VC. Correlates of vaccine protection from influenza and its complications. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:34–44. doi: 10.4161/hv.8.1.18214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempe A, Hall CB, MacDonald NE, Foye HR, Woodin KA, Cohen HJ, et al. Influenza in children with cancer. J Pediatr. 1989;115:33–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coudeville L, Bailleux F, Riche B, Megas F, Andre P, Ecochard R. Relationship between haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody titres and clinical protection against influenza: development and application of a bayesian random-effects model. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng S, Fang VJ, Ip DK, Chan KH, Leung GM, Peiris JS, et al. Estimation of the association between antibody titers and protection against confirmed influenza virus infection in children. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1320–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black S, Nicolay U, Vesikari T, Knuf M, Del Giudice G, Della Cioppa G, et al. Hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers as a correlate of protection for inactivated influenza vaccines in children. Pediatric Infect Dis J. 2011;30:1081–5. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182367662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodewes R, Fraaij PL, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Pediatric influenza vaccination: understanding the T-cell response. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11:963–71. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu C, Openshaw PJ. Antiviral B cell and T cell immunity in the lungs. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:18–26. doi: 10.1038/ni.3056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosmidis S, Baka M, Bouhoutsou D, Doganis D, Kallergi C, Douladiris N, et al. Longitudinal assessment of immunological status and rate of immune recovery following treatment in children with ALL. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:528–32. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perkins JL, Harris A, Pozos TC. Immune dysfunction after completion of childhood leukemia therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:1–5. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakim H, Allison KJ, Van De Velde LA, Li Y, Flynn PM, McCullers JA. Immunogenicity and safety of inactivated monovalent 2009 H1N1 influenza A vaccine in immunocompromised children and young adults. Vaccine. 2012;30:879–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reilly A, Kersun LS, McDonald K, Weinberg A, Jawad AF, Sullivan KE. The efficacy of influenza vaccination in a pediatric oncology population. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:e177–81. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181d869f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castrucci MR. Factors affecting immune responses to the influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1338547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kersun LS, Reilly A, Coffin SE, Boyer J, Luning Prak ET, McDonald K, et al. A prospective study of chemotherapy immunologic effects and predictors of humoral influenza vaccine responses in a pediatric oncology cohort. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:1158–67. doi: 10.1111/irv.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ottoffy G, Horvath P, Muth L, Solyom A, Garami M, Kovacs G, et al. Immunogenicity of a 2009 pandemic influenza virus A H1N1 vaccine, administered simultaneously with the seasonal influenza vaccine, in children receiving chemotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1013–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr SB, Adderson EE, Hakim H, Xiong X, Yan X, Caniza M. Clinical and demographic characteristics of seasonal influenza in pediatric patients with cancer. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:e202–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318267f7d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman JL, Reilly AF, Powell SC, Bailey LC. Quality improvement initiative to increase influenza vaccination in pediatric cancer patients. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e540–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn HE, Snelling TL, Habig A, Chiu C, Spokes PJ, McIntyre PB. Parental Tdap boosters and infant pertussis: a case-control study. Pediatrics. 2014;134:713–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson MG, Naleway A, Fry AM, Ball S, Spencer SM, Reynolds S, et al. Effects of repeated annual inactivated influenza vaccination among healthcare personnel on serum hemagglutinin inhibition antibody response to A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like virus during 2010–11. Vaccine. 2016;34:981–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Sabaiduc S, De Serres G, Winter AL, Dickinson JA, et al. A perfect storm: impact of genomic variation and serial vaccination on low influenza vaccine efectiveness during the 2014–2015 season. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:21–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vu D, Peck AJ, Nichols WG, Varley C, Englund JA, Corey L, et al. Safety and tolerability of oseltamivir prophylaxis in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a retrospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;15:187–93. doi: 10.1086/518985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okoli GN, Otete HE, Beck CR, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS. Use of Neuraminidase Inhibitors for Rapid Containment of Influenza: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Individual and Household Transmission Studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang K, Shun-Shin M, Gill P, Perera R, Harnden A. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD002744. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002744.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]