Abstract

Background

Targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway has improved outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC), however resistance inevitably occurs. CD105 (endoglin) is an angiogenic pathway which is strongly upregulated after VEGF inhibition, potentially contributing to resistance. We tested whether TRC105, a monoclonal antibody against endoglin, impacted disease control in previously treated RCC patients receiving bevacizumab.

Methods

Eligible patients with metastatic RCC previously treated with 1–4 prior lines of therapy, including VEGF-targeted agents, were randomized 1:1 to bevacizumab 10 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks (Arm A) or the same plus TRC105 10 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks (Arm B). The primary endpoint was progression-free survival at 12 and 24 weeks. Correlative studies included serum TGFb and sCD105, as well as tissue immunostaining for TGFb receptors.

Results

Fifty nine subjects were enrolled (28 on Arm A and 31 on Arm B); 1 on each arm had a confirmed PR. Median PFS for bevacizumab alone was 4.6 months, compared to 2.8 for bevacizumab + TRC105 (p=0.09). Grade ≥3 toxicities occurred in 16 (57%) of subjects treated with bevacizumab, compared to 19 (61%) treated with bevacizumab + TRC105 (p=0.9). Baseline serum TGFβ below the median (<10.6) was associated with longer median PFS (5.6 vs 2.1, p=0.014).

Conclusions

TRC105 failed to improve progression-free survival when added to Bevacizumab. TGFβ warrants further study as a biomarker in RCC.

Keywords: renal cancer, VEGF, TGFβ, targeted therapy, angiogenesis

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) affected more than 62,000 people in the United States in 2016, and to cause more than 14,000 deaths1. The prognosis in clear cell RCC has been substantially improved by targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, based on the biology of von-Hippel Lindau gene inactivation being a driver genomic change2–5. Angiogenesis is a foundational developmental process with multiple redundant pathways, which may contribute to innate or acquired resistance to VEGF-targeted therapy. CD105, or endoglin, is one of the essential pathways for angiogenesis6. Activation of CD105 by TGFβ results in stimulation of endothelial cell proliferation through the TBR-II/ACVRL1/TGFBR1 heterotetrameric receptor complex7. In addition, tumor cells themselves can express CD105, in particular renal cancer cells8, and higher expression is associated with poorer outcomes9. Tumor microvessels, which remain after exposure to anti-VEGF antibody in animal experiments, exhibit strong expression of CD10510, and CD105 is one of 3 genes whose expression is upregulated by suppression of VEGF signaling11. Inhibition of CD105 should impede signaling by TGFβ, potentially shutting off an escape pathway during VEGF blockade. TRC105 is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody that binds human CD105 and induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and reduction in the development of metastases in colon cancer xenograft models12. A phase I study identified 10 mg/kg intravenously every week or 15 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks as the recommended phase II dosing schedules for TRC105, and anti-tumor effects were seen13. Low grade first-dose infusion reactions were observed, reflecting antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity and necessitating premedication that is tapered off with repeat dosing. Grade 3 or higher toxicities included anemia (n=4, 8%) but hypertension and proteinuria were notably absent.

Bevacizumab (Bev) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against VEGF which gained FDA approval for the treatment of metastatic RCC based on significant prolongation of progression-free survival for the combination of Bev plus interferon over interferon alone14. Even in this population of previously untreated patients, 20% of patients had primary refractory disease, with best response of progressive disease on the bevacizumab arm. This creates interest in dual anti-angiogenic blockade, though to date combination therapy has been limited by excess toxicity15,16. A phase I trial combining TRC105 with Bev found DLT of headache at doses of 6 mg/kg TRC105 with 15 mg/kg bevacizumab; subsequent adjustments to the TRC105 administration (splitting the first dose and staggering the first dose administration off of the same day as Bev) led to successful escalation of TRC105 to 10 mg/kg with 10 mg/kg Bev17. The hypothesis that adding TRC105 to Bev would suppress an escape pathway for VEGF inhibition and result in delay to disease progression, led to the development of this clinical trial of bevacizumab alone or with TRC105 in patients with metastatic RCC. Bevacizumab has been more tolerable in vertical and horizontal angiogenesis combinations whereas toxicity has limited success of VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors in combination studies; this was the rationale for selecting bevacizumab.

Methods

Patients were eligible if they had metastatic RCC, with any histologic subtype. Prior treatment with at least one targeted therapy for metastatic RCC was required, including cytokine, VEGF or mTOR agents, with a maximum of 4 prior systemic therapies and excluding prior Bev. Hemoglobin levels ≥ 9 g/dL were required for study entry, as well as glomerular filtration rate calculated or measured at >50 mL/min, normal bilirubin and AST/ALT < 2.5 x the institutional upper limit of normal (up to 5x for patients with liver metastases). Patients receiving full-dose anticoagulation were excluded from participation, as well as patients with history of a bleeding diathesis, or a venous thromboembolic event within one year. Patients were randomized 1:1 to Arm A or B, stratified to maintain balance with respect to clear-cell versus non-clear-cell disease, and ECOG performance status of 0–1 versus 2. Randomization tables for each of 4 strata, each with block size of 4, were generated by the statistician and held in confidence at the data coordinating center, accessible to only the two registrars. Subjects were treated at the clinical practices constituting the California Cancer Consortium between November 9, 2012 and August 28, 2014. The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov NCT01727089.

Bev was administered at 10 mg/kg IV on day 1 and 15 of 28-day cycles as a single agent (Arm A) or with TRC105 10 mg/kg IV on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 (Arm B). The first dose of TRC105 was to be split; thus patients on Arm B received Bev alone on cycle 1 day 1, 3 mg/kg TRC105 on day 8, 7 mg/kg TRC105 on day 11, and then the first concurrent full doses of both medications on cycle 1 day 15. These initial doses were infused over 4 hours until the full 10 mg/kg dose was tolerated (i.e. cycle 1 day 15 dose), at which point the duration of infusion was decreased, beginning with cycle 1 day 22 (down to 2 hours) and if that was tolerated, then the infusion time was decreased to 1 hour for all subsequent doses. Premedication with dexamethasone, 20 mg IV, was utilized until the 1 hour infusion schedule was tolerated; at that point it was tapered off. Additional required premedications for TRC105 included acetaminophen, H1 and H2 blockers. The first 3 subjects on Arm B received 8 mg/kg TRC105, split 3 and 5 mg/kg, and staggered; the starting dose was changed to 10 mg/kg once the phase I safety data became available. There were no other major changes to eligibility or treatment during the study.

The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) evaluated using two-point analysis (12 and 24 weeks) proposed by Freidlin18. Withdrawl without radiographic SD or better was included as clinical progression, but this made no qualitative difference in the results. Imaging was performed every 12 weeks +/− 1 week. A total of 88 pts were to be randomized to provide 80% power to detect an increased PFS for the combination therapy from 61% to 78% at 12 weeks and 37% to 60% at 24 weeks, with an α=0.1. An interim analysis for futility was conducted after 44 patients had 12-week PFS evaluated.

Blood for correlative studies was drawn at baseline, and before cycle 2 and 4. ELISA was performed using kits from Abcam. Changes in serum TGFβ from baseline after treatment were evaluated and compared overall and between arms using a general linear mixed effects model. Paraffin-embedded tissue samples from biopsy or nephrectomy were evaluated for expression of TGFβR1&2 and AVCRL via immunohistochemistry using antibodies from R&D systems. Tissue data and baseline ELISA data were evaluated for association with PFS using Kaplan-Meier plots and the logrank test.

Results

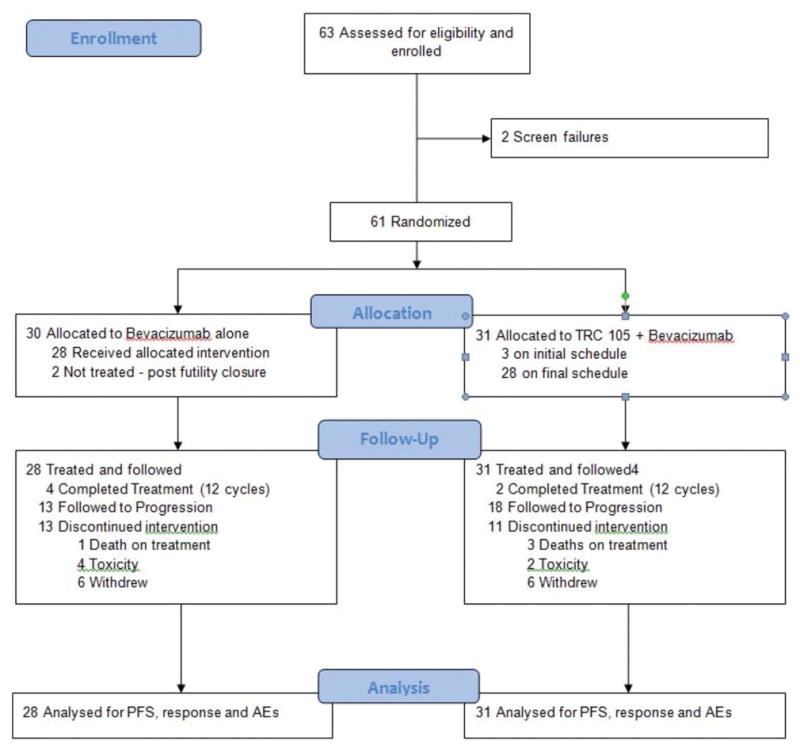

After approval by individual institutional review boards for participating centers, 59 subjects were accrued. Enrollment commenced November 2012 and was halted in September 2014 when interim analysis for futility revealed that the continuation criterion was unachievable. Accrual is summarized in the CONSORT diagram, Figure 1. Baseline and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1; 46 patients (78%) had clear cell histology and 13 (22%) had non-clear cell RCC. Two patients on each arm had received only temsirolimus as their prior therapy, and one patient on arm A had only received erlotinib + ARQ197 on clinical trial; otherwise all patients were VEGF-pretreated. Of the 4 with only temsirolimus as prior therapy, there was a PR with 12 month PFS on Arm A, and an unconfirmed PR with 12 month PFS on Arm B, as well as a progression at month 1 on each arm. The arm A patient pre-treated with ARQ 197+ERLOTINIB had stable disease, progressing at 9 months.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram depicting subject accrual, randomization

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Characteristic | Arm A Bevacizumab alone (N=28) |

Arm B Bevacizumab + TRC105 (n=31) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age: median (range) | 58 (25–82) | 65 (24–78) |

|

| ||

| Gender: number (%) | ||

| Male | 20 (71%) | 24 (77%) |

| Female | 8 (29%) | 7 (23%) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity: number (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 6 (21%) | 4 (13%) |

| Asian | 3 (11%) | 0 |

| Black | 2 (7%) | 2 (6%) |

| Caucasian | 17 (61%) | 25 (81%) |

|

| ||

| Prior nephrectomy: number (%) | 22 (79%) | 22 (71%) |

|

| ||

| Histology: | ||

| Clear cell | 21 (75%) | 25 (81%) |

| Papillary | 2 (7%) | 1 (3%) |

| Carcinoma, NOS | 5 (18%) | 5 (16%) |

|

| ||

| Prior lines of therapy: | ||

| 1 | 9 (32%) | 9 (29%) |

| 2 | 10 (36%) | 12 (39%) |

| 3 | 8 (29%) | 7 (22%) |

| 4 | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) |

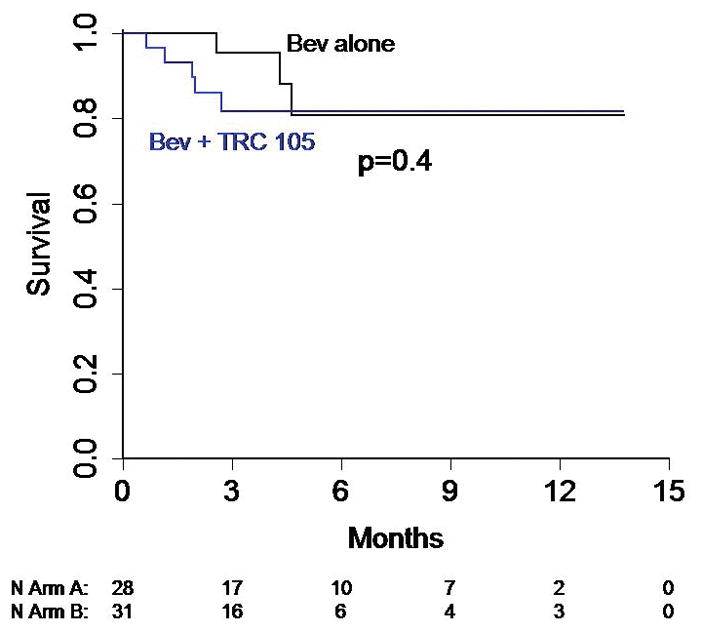

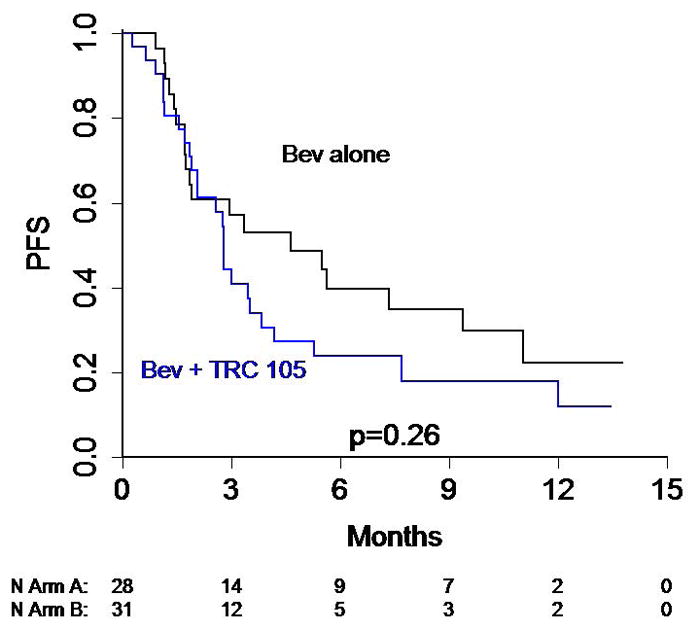

A summary of treatment administration and response is presented in Table 2. One subject on each arm had a confirmed PR with 8/28 (28.6%) on arm A and 6/31 (19.4%) on arm B having stable disease on at least two evaluations (24+ weeks). Median PFS for the study population overall was 3.0 months (95% CI 2.1, 5.5), or 3.5 months if withdrawals without imaging are censored. Median PFS for bevacizumab alone was 4.6 months, compared to 2.8 for bevacizumab + TRC105 (p=0.09). Time to failure curves are presented in Figure 2, and are not significantly different (logrank p = 0.09); this parameter was chosen to eliminate the effect of post-treatment follow-up on non-progressed patients. Because imaging times departed somewhat from the planned 12 and 24 weeks, we note that 46% on Bev alone versus 42% on Arm B had a first evaluation of SD or better, while 29% and 23% had a second evaluation of SD or better. PFS was similar for subjects with clear cell versus non clear cell histology (median PFS 2.8 months on arm B vs 4.2 for Arm A, logrank p = 0.26).

Table 2.

Treatment summary, including cycles of study therapy and best radiographic response.

| Arm A Bevacizumab alone (N=28) |

Arm B Bev + TRC105 (N=31) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Median # of cycles (range) | 3 (1–12) | 3 (1–12) |

|

| ||

| Reason for discontinuation | ||

| Progression of disease | 13 (46%) | 18 (64%) |

| Toxicity | 4 (14%) | 2 (6%) |

| Treatment completed | 4 (14%) | 2 (6%) |

| Withdrew consent | 6 (21%) | 6 (19%) |

| Death | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) |

|

| ||

| Best Radiographic Response | Number (%) | Number (%) |

| CR | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 1 (4%) | 1 (3%) |

| SD | 12 (36%) | 12 (39%) |

| PD | 8 (29%) | 11 (35%) |

| No repeat imaging | 7 (25%) | 7 (23%) |

|

| ||

| Progression Free Survival | ||

| PFS at 12 weeks | 69% (53, 90) | 56% (41, 77) |

| PFS at 24 weeks | 54% (37, 79) | 25% (13, 47) |

| Median PFS | 4.6 months (1.8, NA) | 2.8 months (2.1, 4.2) |

| Clear Cell median PFS | 3.35 months (1.7, NA) n=21 | 2.8 months (1.9, NA) n=6 |

| Non-Clear Cell median PFS | 5.5 mo (1.3, NA)* n=7 | 3.2 months (2.1, NA) n=25 |

this is based on a small # of events, 3 (of 7 patients in this subgroup)

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Curves depicting (A) overall survival and (B) time to treatment failure for the study arms.

Toxicities are summarized in Table 3. Grade 3 or higher toxicities occurred in 16 (57%) of subjects treated with Bev alone, compared to 19 (61%) treated with Bev + TRC105 (p=0.9). Grade 3 or higher anemia, fatigue, pulmonary and gastrointestinal toxicities were more common on the Bev + TRC105 arm, whereas grade 3 or higher cardiac and bleeding events as well as proteinuria were more common with Bev alone. Bleeding from oral mucosa was the most common manifestation of bleeding on the TRC105 arm whereas on the bevacizumab monotherapy arm hemorrhage occurred more commonly from gastrointestinal or respiratory source.

Table 3.

number and (%) of patients experiencing each adverse event, stratified treatment arm and by severity (CTC AE grade 1 or 2, grade 3 or 4).

| Event | Arm A (Bevacizumab) N=28 |

Arm B (Bevacizumab + TRC105) N=31 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Grade 1 or 2 | Grade 3 or 4 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade 3 or 4 | |

|

| ||||

| Cardiovascular | ||||

| Heart Failure | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 8 (28.6%) | 5 (17.9%) | 11 (35.5%) | 4 (12.9%) |

|

| ||||

| Constitutional | ||||

| Fatigue | 6 (21.4%) | 0 | 11 (35.5%) | 2 (6.5%) |

| Anorexia | 6 (21.4%) | 0 | 9 (29%) | 1 (3.2%) |

| Infusion Reaction | 1 (3.5%) | 0 | 4 (12.9%) | 2 (6.5%) |

| Rash | 1 (3.5%) | 0 | 12 (38.7%) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 1 (3.5%) | 3 (10.7%) | 3 (9.7%) | 3 (9.7%) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 10 (35.7%) | 0 | 13 (41.9%) | 5 (16.1%) |

|

| ||||

| Hematologic | ||||

| Anemia | 3 (10.7%) | 4 (14.3%) | 8 (25.8%) | 8 (25.8%) |

| Bleeding | 3 (10.7%) | *2 (7%) | 9 (29%) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (17.9%) | 0 | 2 (6.5%) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Metabolic | ||||

| Hypercalcemia | 4 (14.3%) | 0 | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (6.5%) |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 1 (3.5%) | 9 (29%) | 2 (6.5%) |

|

| ||||

| Neurologic | ||||

| Dizziness | 6 (21.4%) | 0 | 4 (12.9%) | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 5 (16.1%) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Renal | ||||

| Incr. creatinine | 6 (21.4%) | 0 | 4 (12.9%) | 0 |

| Hematuria | 4 (14.3%) | 0 | 2 (6.5%) | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 9 (32.1%) | 2 (7%) | 5 (16.1%) | 0 |

one event was grade 5

54 subjects (24 on Bev and 28 on Bev+TRC105) had baseline serum sample sufficient for correlative study analysis; 14 treated with Bev, 19 with Bev + TRC105 had both baseline and cycle 2 samples. Results are summarized in Table 4. Mean CD105 was 82.8 pg/mL (95% CI 64.6, 106.2) at baseline. In patients treated with Bev alone, sCD105 levels did not increase post treatment; mean 59.03 (95% CI 43.20, 80.67). Post-treatment sCD105 levels were not evaluated in the Bev + TRC105 arm due to potential for assay interference. Mean TGFβ levels were 8.12 ng/mL (95% CI 6.44, 10.25) at baseline in Arm 1 and increased to mean 13.24 ng/mL (95% CI 8.44, 20.75) at cycle 4 while mean baseline levels were 9.86 ng/mL (95% CI 7.98, 12.20) in Arm 2 and decreased to 8.52 ng/mL (95% CI 5.60, 12.96) at cycle 4. These changes in TGFβ levels were not significant within groups (p=0.66) nor were post-treatment levels significantly different between arms (p=0.17). Baseline serum TGFβ below the median (<10.6) was associated with higher median PFS (7.3 vs 2.6, p=0.02); baseline CD105 was not (p=0.83). Tissue was available for 29 subjects. No tissue markers (TGFβR1 &2 or AVCRL) were associated with longer PFS except, in exploratory analysis, higher TGFβR2 staining was associated with longer PFS in patients treated with TRC105 median PFS 3.8 months for 11 pts staining 2+ vs 1.8 months for 5 pts staining 1+ and 2 pts at 0 (p=0.03).

Table 4.

Summary of correlative blood and tissue markers and relationship to PFS.

| Correlate | Grouping for Analysis | All Patients (both Arms Combined) | Logrank p-value for Association with PFS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12-wk PFS | 24-wk PFS | |||

| TGF-β R1 (IHC) | 0 | 14 | 0.55 +/− 0.14 | 0.46 +/− 0.14 | 0.76 |

| 1–2 | 15 | 0.43 +/− 0.13 | 0.32 +/− 0.14 | ||

| TGF-β R2 (IHC) | 0–1 | 15 | 0.40 +/− 0.13 | 0.30 +/− 0.13 | 0.36 |

| 2 | 15 | 0.55 +/− 0.14 | 0.46 +/− 0.14 | ||

| AVCRL (IHC) | 0–1 | 16 | 0.38 +/− 0.12 | 0.38 +/− 0.12 | 0.43 |

| 2 | 13 | 0.57 +/− 0.15 | 0.46 +/− 0.16 | ||

| CD105 (ELISA) | < 64.07 | 24 | 0.53 +/− 0.11 | 0.37 +/− 0.11 | 0.83 |

| > 64.07 | 24 | 0.57 +/− 0.10 | 0.32 +/− 0.11 | ||

| TGF-β (ELISA) | < 10.60 | 24 | 0.78 +/− 0.09 | 0.49 +/− 0.12 | 0.022 |

| > 10.60 | 24 | 0.30 +/− 0.10 | 0.19 +/− 0.09 | ||

Discussion

The primary endpoint of this randomized study was negative, namely addition of TRC105 to Bev failed to increase PFS significantly in a population of heavily pretreated patients with metastatic RCC. Nevertheless, the study yielded several important pieces of information. First, these data provide novel insight into responses and PFS with Bevacizumab monotherapy in the 2nd line setting and beyond. Prospective data have previously been unavailable to practicing physicians and can help inform discussions when considering use of bevacizumab monotherapy in VEGF-pretreated patinets. One retrospective report identified 1 patient treated with Bev + interferon in the 3rd line setting with a PFS of 3 months, 2 treated in the 4th line setting with a PFS of 1.6 months and 5 treated in the 5th line setting with a PFS of 26.2 months19. For benchmarking purposes, there has been a randomized trial in the 3rd line setting comparing two VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitors, dovitinib and sorafenib, in which median PFS was 3.6 months20. In this trial, the overall population PFS of 3.5 months with bevacizumab-based therapy thus appears similar to other agents in the salvage setting. Second, the trial included a substantial population of patients with non-clear cell RCC and present unique data about response to bevacizumab in this group. Patients with mixed clear cell and non-clear cell were allowed on the registrational trial of Bev/IFN, but outcomes were not reported separately for these groups of patients14. In this study, disease stabilization did occur in non-clear cell RCC treated with bevacizumab alone or in combination, with similar PFS. Third, the toxicity profile in this study is notable for relatively few constitutional and gastrointestinal side effects, which contrasts with VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. This may become more relevant now, as there are increasing options for patients already exposed to VEGF therapy, and may be useful to patients and physicians weighing relative risks and benefits of treatment options.

In this study, the high rate of patients (25%) who stopped therapy prior to radiographic evaluation may reflect the enrollment of rapidly progressing patients who are less likely to benefit.. Nevertheless, there are several hypotheses which could also account for the negative trial results, and numerically inferior PFS in the combination group (2.8 months compared to 4.6 months for Bev alone). One possibility would be interference of the two antibodies with each other in vivo, which would explain the trend of the combination arm having lower rate of PFS at 12 and 24 weeks. However, the fact that there was no significant difference in VEGF on-target toxicities, such as hypertension and proteinuria, between arms argues against this hypothesis. Furthermore, the fact that responses and disease stabilization were seen on the combination arm as well as the bevacizumab alone arm, without statistical inferiority, also suggests VEGF inhibition occurred in the combination group. An unexpected pro-growth effect of TRC105 would be another possible explanation, but this is unlikely since phase I and ongoing clinical trial data have not identified increased risk of disease progression in patients receiving this agent. Serum CD105 levels actually decreased after treatment with Bev rather than increasing, contrary to the tissue preclinical data in which CD105 expression is upregulated by VEGF inhibition. This could be an issue of targeting VEGF ligand rather than receptor or that tissue is the better place to look for receptor signaling changes. An ongoing study of axitinib alone or in combination with TRC105 will provide further data regarding the utility of targeting CD105 upregulation as a way of preventing resistance to VEGF suppression (NCT01806064). Phase 1b study found that full dose axitinib was tolerable with TRC105 dosed at 10 mg/kg, and showed promising activity with RECIST PR in 5/17 (29%) of patients, some of whom were heavily pre-treated21.

The study also tested the hypothesis that tissue levels of TGFβ receptor expression would be related to treatment response: since CD105 is required for heterodimerization and signaling activation by TGFβ, tumors using more TGFβ were postulated to be more sensitive to CD105 inhibition. Although the study had limited power to detect differences, given relatively few patients had long PFS and not all patients’ samples were available for analysis, there was a hypothesis-generating finding of longer PFS in subjects with higher expression of TGFβR2 when patients were treated with TRC105. Although not significantly different, the rise in mean serum TGFβ in Arm 1 patients (without TRC105) compared to the decrease in Arm 2 patients, suggesting decreased TGFβ signaling with CD105 inhibition. This is provocative in terms of proof of concept, despite having been underpowered and fits with emerging data from the study of TRC105 + axitinib, in which investigators found that higher plasma levels of TGFβR3 were associated with greater likelihood of response23. Overall, these data support further study of TGFβ pathway expression to yield potential predictive markers in future studies of patients with advanced RCC and particularly in the setting of treatment with TRC105.

Conclusions

TRC105 added to Bev was not associated with longer PFS compared to Bev alone in the second through fourth line treatment setting in metastatic RCC patients. Bevacizumab is associated with poor activity in this population. TGFβ warrants further study as a biomarker in RCC.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number UM1CA186717 and NO1-CM-2011-00038. Additional support was provided under NIH award numbers P30CA33572, P30CA093373, P30CA014089, and P30CA014089 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure:

TBD: consultant for Bayer, Genentech, Pfizer. Speaker for Astellas, Dendreon, Exelixis. JL: none. SKP: WS: MF: consultant to Bayer, Alkermes, Medivation; speaker for Dendreon. UV: AR: JP: consultant for Aeterna-Zentaris, Astellas, Bayer, Dendreon, Janssen, Millenium

Presented in part at: ASCO annual meeting 2015 (abstract 4542) and 2016 (abstract 522)

Author contributions: The clinical trial was designed by TD, JL, JH, DIQ, PNL. Correlative studies were performed in the laboratory of JP with TD planning and analyzing. Main statistical analysis was performed by JL, with input from TD, UV, DIQ, PNL. Day-to-day management during the clinical trial was performed by TD, SP, WS, MF, UV, AR, JP, JH, DIQ, PNL with TD taking primary responsibility. Data Curation: clinical TD, JL; correlative JP. Writing- original draft: TD, JL. Writing- Review/Editing: TD, JL, SP, WS, MF, UV, AR, JP, JH, DIQ, PNL. Project Administration: TD, PNL; funding acquisition: DIQ, PNL with support from the California Cancer Consortium.

Contributor Information

Tanya B. Dorff, USC Keck School of Medicine, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Jeff Longmate, City of Hope.

Sumanta K. Pal, City of Hope.

Walter Stadler, University of Chicago.

Mayer Fishman, Moffitt Cancer Center.

Ulka Vaishampayan, Karmanos Cancer Center.

Amol Rao, USC Keck School of Medicine, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Jacek Pinksi, USC Keck School of Medicine, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

James Hu, USC Keck School of Medicine, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

David I. Quinn, USC Keck School of Medicine, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Ctr.

Primo N. Lara, Jr., UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alpha in metastatic renal cell cancer. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. New Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li DY, Soresen LK, Brooke BS, et al. Defective angiogenesis in mice lacking endoglin. Science. 1999;284:1534–7. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolan-Stevaux O, Zhong W, Culp S, et al. Endoglin requirement for BMP9 signaling in endothelial cells reveals new mechanism of action for selective anti-endoglin antibodies. PLOS-One. 2012;7:e50920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandlund J, Hedberg Y, Bergh A, et al. Endoglin (CD105) expression in human renal cell carcinoma. BJU International. 2006;97:706–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dallas NA, Samuel S, Xia L, et al. Endoglin (CD105) : a marker of tumor vasculature and potential target for therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis DW, Inoue K, Dinney CP, et al. Regional effects of an antivascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody on receptor phosphorylation and apoptosis in human 253J B-V bladder cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4601–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-2879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bockhorn M, Tsuzuki Y, Xu L, et al. Differnetial vascular and transcriptional responses to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody in orthotopic human pancreatic cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seon BK, Haba A, Matsuno F, et al. Endoglin-targeted cancer therapy. Curr Drug Deliv. 2011;8:135–143. doi: 10.2174/156720111793663570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen LS, Hurwitz HI, Wong MK, et al. A phase I first-in-human study of TRC105 (anti-endoglin antibody) in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4820–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewki P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2103–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azad NS, Posadas EM, Kwitkowski VE, et al. Combination targeted therapy with sorafenib and bevacizumab results in enhanced toxicity and antitumor activity. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3709–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman DR, Baum MS, Ginsberg MS, et al. Phase I trial of bevacizumab plus escalating doses of sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1432–39. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon MS, Robert F, Matei D, et al. An open-label phase Ib dose-escalation study of TRC105 (anti-endoglin antibody) with bevacizumab in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:5918. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freidlin B, Korn EL, Hunsberger S, et al. Proposal for the use of progression-free survival in unblinded randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2007:2122–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vallet S, Pahernik S, Hofner T, et al. Efficacy of targeted treatment beyond third line therapy in metastatic kidney cancer: retrospective analysis from a large-volume cancer center. Clin GU Cancer. 2015;13:e145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motzer RJ, Porta C, Vogelzang NJ, et al. Dovitinib versus sorafenib for third-line targeted treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an open-label, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:286–96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choueiri TK, Michaelson MD, Posadas EM, et al. A Phase 1b dose-escalation study of TRC105 (anti-endoglin antibody) in combination with axitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. ESMO. 2015 doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0299. abstr 804p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-β signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nature Gen. 2001;29:117–29. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]