Abstract

p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 act as tumour suppressors through induction of cellular senescence. However, senescence-independent roles of these CDK inhibitors are not well understood. Here, we report an unexpected function of p16Ink4 and p21Cip1/Waf1, namely, tumour promotion through chemotaxis. In monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (Mo-MDSCs), p16Ink4 and p21Cip1/Waf1 are highly expressed and stimulate CX3CR1 chemokine receptor expression by preventing CDK-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of SMAD3. Thus, deletion of p16 Ink4 and p21 Cip1/Waf1 reduces CX3CR1 expression, thereby inhibiting Mo-MDSC accumulation in tumours expressing CX3CL1 and suppressing the tumour progression in mice. Notably, blockade of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis suppresses tumour growth, whereas inactivation of CDKs elicits the opposite effect. These findings reveal an unexpected function of p16 Ink4a and p21 Waf1/Cip1 and indicate that regulation of Mo-MDSCs chemotaxis is a valuable potential strategy for control of tumour development.

Both p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 are known oncosuppressors and have a role in senescence. Here, the authors show a pro-tumorigenic role for these two proteins: high expression in myeloid-derived suppressor cells stimulates their chemotactic function, favouring tumour progression.

Introduction

The p16 Ink4a and p21 Waf1/Cip1 genes, which encode cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, are upregulated in cultured mammalian primary cells upon detection of various potentially oncogenic stimuli1,2. This unique feature of p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1, together with their ability to induce irreversible cell cycle arrest (termed cellular senescence), suggests that these genes act as a safeguard against neoplasia3–5. Indeed, mice lacking p16 Ink4a and/or p21 Waf1/Cip1 exhibit early onset of cancer6–9, illustrating the importance of p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 in tumour suppression in vivo. To observe the physiological roles of p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 during tumour formation, we previously generated transgenic mice lines expressing firefly luciferase under the control of the p16 Ink4a or p21 Waf1/Cip1gene promoters; these were termed p16-luc or p21-luc mice, respectively, and we revealed the timing, and hence, the likely roles of p16Ink4a and/or p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in de novo tumorigenesis in vivo10,11.

Similar to our work, Burd et al. reported the generation of another strain of p16 Ink4a reporter mice (p16 Luc mice), in which the p16 Ink4a coding sequence was replaced with cDNA encoding firefly luciferase12. Notably, in addition to ageing and de novo tumorigenesis, p16Ink4a expression was strikingly induced in the stroma of developing neoplasia. Lethal irradiation coupled with bone marrow (BM) transplantation from syngeneic p16 Luc mice indicated the presence of p16 Ink4a-expressing BM-derived cells in the tumour microenvironment12. However, it is not known which cell types express p16Ink4a in the stroma of developing neoplasia. Moreover, the biological role of p16Ink4a expression in these cancer stromal cells remains unclear.

In this study, we found that both p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 are highly expressed in myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) without any noticeable senescence-associated phenotypes. MDSCs are known to negatively regulate immune responses and facilitate tumour progression13. The systemic expansion of MDSCs in BM and the MDSC migration to peripheral are the hallmarks of tumour-bearing condition14. In mice, MDSCs are defined as Gr-1+CD11b+ cells and categorised into 2 subtypes: polymorphonuclear (PMN-) and monocytic (Mo-) MDSCs15,16. Mo-MDSCs are a CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G− subset that is highly immunosuppressive and exerts its effects in both antigen-specific and antigen-non-specific manners15,16. In contrast, CD11b+Ly6CintLy6G+ PMN-MDSCs are moderately immunosuppressive and act via antigen-specific mechanisms15,16. Mo- and PMN-MDSCs differ markedly in terms of the molecular mechanisms involved in their migration/chemotaxis. Mo-MDSCs express C-C chemokine receptor type (CCR)2, CCR5 and CX3C chemokine receptor (CX3CR)117,18, whereas PMN-MDSCs express CXCR219. The accumulation of intratumoural MDSCs dependent on these chemokine receptors is well correlated with tumour growth17,19.

In the present study, we reveal that p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 upregulate CX3CR1 expression by preventing CDK-mediated phosphorylation and inactivation of SMAD3 in Mo-MDSCs. Thus, deletion of p16 Ink4a and p21 Waf1/Cip1 in mice results in a substantial decrease in infiltration of Mo-MDSCs into tumours and causes slower growth of tumour allografts. Conversely, inactivation of CDKs by chemical inhibitors increases the expression of CX3CR1 in Mo-MDSCs, resulting in accumulation of Mo-MDSCs in tumours and consequent acceleration of tumour growth in allograft mouse models. These results uncover a novel function of p16Ink4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 in MDSC chemotaxis, and provide valuable new insight into how to bypass this undesirable side effect of CDK inhibitors.

Results

p16 and p21 are expressed in MDSCs in tumour-bearing mice

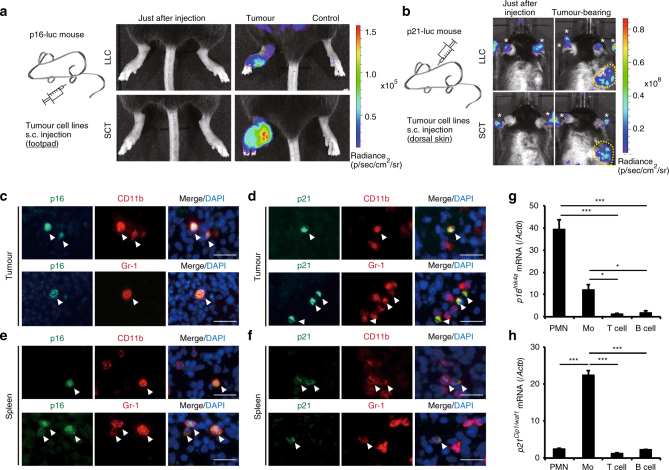

We previously performed in vivo imaging of p16Ink4a or p21Cip1/Waf1 expression in mice and elucidated the dynamics of their expression during the development of skin cancer, using p16-luc or p21-luc mice9–11. This approach, together with the analysis of p16 Ink4a and/or p21 Cip1/Waf1-knockout mice, suggested that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 are likely to be expressed in premalignant benign tumour cells, thereby having a protective role against malignant transformation. However, we were unable to exclude the possibility of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 expression in non-tumour cells within the tumour microenvironment in these experimental settings. Thus, to ascertain this possibility, we inoculated p16- and p21-luc mice with syngeneic cancer cell lines, such as Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) or spindle cell tumour (SCT) cells, neither of which expresses luciferase. Notably, inoculation of these cancer cell lines induced significant levels of luciferase activity in the area of tumour formation, but not in contralateral Matrigel-injected areas, in both p16-luc and p21-luc mice (Fig. 1a, b). This is consistent with a previous report describing the presence of BM-derived p16 Ink4a-expressing stroma cells in the tumour microenvironment12. Collectively, these results lead us to an idea that the expression of p16Ink4a and/or p21Cip1/Waf1 may have important roles in establishing the tumour microenvironment during cancer development.

Fig. 1.

Tumour-induced MDSCs express p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1. a p16-luc mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in the left footpad with LLC (3 weeks after injection; upper panels) or SCT (6 weeks after injection; lower panels) cells. The right footpad was injected with matrigel vehicle alone as a negative control. Representative bioluminescence images of mice just after tumour injection or tumour-bearing mice are shown. b Representative bioluminescence images of p21-luc mice that received s.c. injection of LLC (2 weeks after injection; upper panels) or SCT (4 weeks after injection; lower panels) cells in the dorsal area. Tumour areas are indicated by dotted circles; asterisks indicate signals from paws and ears. c–f Representative immunohistological images of tumour (c, d) and spleen (e, f) in an SCT-bearing mouse labelled with p16 (c, e) or p21 (d, f) antibodies (green) and either CD11b or Gr-1 antibodies (red). Arrowheads indicate p16- or p21-positive cells. Tissues were extirpated 3 weeks after SCT injection. Scare bars indicate 40 μm. g, h Expression of p16 (g) and p21 (h) mRNA in splenic PMN-MDSCs (PMN), Mo-MDSCs (Mo), T cells and B cells from SCT-bearing mice at 3 weeks after inoculation, as determined by qRT-PCR (n = 3); data are represented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

To explore this possibility further, we next attempted to identify the cell types expressing p16Ink4a and/or p21Cip1/Waf1 in tumour stroma. In addition to cells in the tumour stroma, spleen cells in tumour-bearing (TB) mice expressed both p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 and were CD11b+ and Gr-1+, as indicated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1c–f). Peripheral CD11b+Gr-1+ cells are known to be MDSCs20 and MDSCs are often induced by the presence of tumours in mice and humans21,22. Accordingly, PMN-MDSCs and Mo-MDSCs were purified from the spleens of tumour-bearing mice, and p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1 mRNA levels were examined by quantitative real-time reverse transcription (qRT-) PCR (Fig. 1g, h). Interestingly, although p16 Ink4a was expressed in both PMN-MDSCs and Mo-MDSCs, p21 Cip1/Waf1 was only expressed in Mo-MDSCs.

As p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 CDK inhibitors have established roles in cellular senescence, we tested if p16Ink4a- and/or p21Cip1/Waf1-expressing MDSCs exhibit senescence-like phenotypes. Consistent with a previous report23, BM Mo-MDSCs are proliferative and the percentage of Mo-MDSCs in the S phase increases in mice lacking both p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1 (p16/p21-DKO mice), compared to in wild-type (WT) mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). On the other hand, in either splenic or intratumoural MDSCs, there is no difference in cell cycle phase distribution between MDSCs from WT mice and those from p16/p21-DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Notably, although proliferation of MDSCs isolated from spleen was rarely detected by a 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 1b), a carboxyfluoroscein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dilution analysis indicated that a substantial amount of these MDSCs (Mo-MDSCs >20%, PMN-MDSCs >60%) resumed proliferation upon stimulation with GM-CSF in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Moreover, other senescence-associated phenotypic characteristics, such as accumulation of γH2AX foci and 53BP1 foci (signs of DNA damage), reduction of lamin B1 expression24, and induction of IL-6 expression25, were not observed in these MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 1d–g). These results, together with the observations that these MDSCs were resistant to ABT-263, a senolytic drug that specifically kills senescent cells26, in both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 1h, i), indicate that these MDSCs are very unlikely to be in a state of cellular senescence despite their high expression of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1. These findings then raise questions about the roles of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 expression in MDSCs.

p16 and p21 in Mo-MDSCs promote tumorigenesis in vivo

MDSCs have been reported to exert immunosuppressive effects and promote tumour development14. To verify the tumour-promoting effect of MDSCs expressing p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1, WT and p16/p21-DKO mice were subcutaneously inoculated with orthotopic SCT cells. Surprisingly, SCT cells grew more slowly in p16/p21-DKO mice than in sex- and age-matched WT mice (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 have a tumour-promoting role, at least in the present experimental setting. The primary function of tumour-derived MDSCs is reportedly immunosuppression, especially inhibition of T cell activation14. We therefore investigated whether p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 are involved in immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs by assessing the activation of T cells co-cultured with MDSCs from WT or p16/p21-DKO mice. Purified PMN- and Mo-MDSCs were added to OVA-pulsed DC2.4 cells, a dendritic cell line27, and to RF33.70 cells, an OVA (SIINFEKL)-specific T-T hybridoma28. T cell activation was evaluated by measuring interleukin (IL)-2 production by RF33.70 cells29. Unexpectedly, however, there was no significant difference in immunosuppressive capacity between WT and p16/p21-DKO MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Similar results were also obtained by performing a co-culture assay of splenic Mo-MDSCs or intratumoural Mo-MDSCs with purified splenic T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody-coated beads (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). In agreement with these observations, expression of the MDSC-derived immunosuppressive factors arginase (Arg)1 30 and nitric oxide synthase (Nos)2 31 was not downregulated in Mo-MDSCs lacking p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1 (Supplementary Fig. 3d). The expression levels of Il1rn, which encodes IL-1RA and promotes tumour growth by inhibiting an inflammatory cytokine IL-1α32, and Cd274, which encodes programmed death ligand (PD-L)1 and kills T cells33, were similar between WT MDSCs and p16/p21-DKO MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Therefore, it is unlikely that the expression of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 in MDSCs is related to T cell suppression. Furthermore, although MDSCs reportedly promote angiogenesis34 and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)35 to assist tumour growth, RNA-sequencing analysis showed that no angiogenesis- or EMT-inducing factors were downregulated in Mo-MDSCs from p16/p21-DKO mice compared with those from WT mice (Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

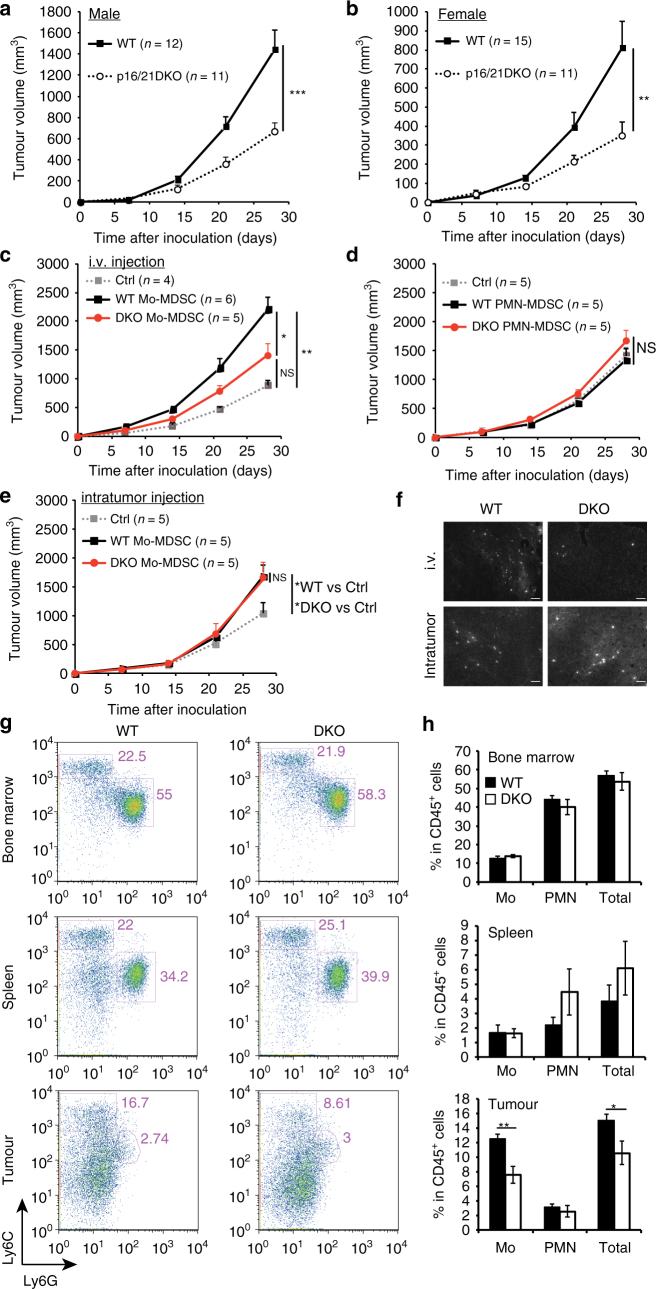

Fig. 2.

p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 in Mo-MDSCs promote tumour progression and the number of intratumoral Mo-MDSCs is decreased in p16/p21-DKO mice. a, b Tumour size in SCT-injected male WT and p16/p21-DKO mice (a) and female WT and p16/p21-DKO mice (b); the number of mice of each genotype is indicated in the data series. c, d Tumour size in WT mice subcutaneously injected with SCT cells simultaneously with adoptive transfer of WT or p16/p21-DKO Mo-MDSCs (c) and PMN-MDSCs (d) via the tail vein. e Tumour size in WT mice subcutaneously injected with a mixture of SCT cells and WT or p16/p21-DKO Mo-MDSCs. f Representative images of tumour slices of mice in which CSFE-labelled Mo-MDSCs from WT or DKO mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) or subcutanously (intratumour). Tumours were extirpated 21 days after injection. Signals indicate CSFE-labelled cells. Scale bars indicate 50 μm. g Representative flow cytometry plots of CD45+CD11b+-gated cells in BM (upper panels), spleen (middle panels), and tumour (lower panels) from WT and p16/p21-DKO mice 3 weeks after SCT cell injection. Cells were labelled with CD45, CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G antibodies. h Mean populations of CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G− (Mo) cells and CD11b+Ly6G+ (PMN) cells in the CD45+-gated cells are shown in f (n = 5); data are presented as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001; NS not significant

We thus next investigated whether the antitumoural phenotype in p16/p21-DKO mice is attributable to MDSC-mediated effects. Indeed, adoptive transfer experiments indicated that Mo-MDSCs purified from p16/p21-DKO mice were less effective in promoting tumour growth than those from WT mice (Fig. 2c). Consistent with a previous report36, transferred PMN-MDSCs did not promote tumour growth regardless of the presence or absence of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 expression (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these results strongly indicate that Mo-MDSCs exhibit differences in terms of tumour growth between WT and p16/p21-DKO mice. It should also be noted that p16Ink4a- and p21Cip1/Waf1-dependent facilitation of tumour growth was observed when Mo-MDSCs were intravenously transferred but not intratumorally transferred (Fig. 2c, e). These results suggest that the failure of Mo-MDSC infiltration into tumour allografts is likely to underlie defects in tumour-promoting activity in p16/p21-DKO mice. Certainly, more intravenously injected WT Mo-MDSCs were observed in the tumour than p16/p21-DKO Mo-MDSCs, but there was no difference in Mo-MDSC infiltration upon intratumoural injection (Fig. 2f). We additionally compared MDSC populations in tumour-bearing WT and p16/p21-DKO mice by flow cytometry. There were no differences between PMN- and Mo-MDSC populations in either the BM or spleen; however, fewer intratumoural Mo-MDSCs were obtained from p16/p21-DKO mice than from WT mice (Fig. 2g, h). Furthermore, more activated (CD44highCD62Llow) CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), but fewer regulatory T cells, which are peripherally expanded by MDSCs37,38, were present in the tumour-draining lymph nodes of p16/p21-DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). In addition, expression of another activation marker, CD69, was increased, and the population of cells positive for PD-139, an exhaustion marker, was decreased in intratumour CD8 T cells of p16/p21-DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 4e–h). Together, these data demonstrate that Mo-MDSC localisation is important for local immunosuppression and consequent tumour development17,40.

CX3CR1 expression is reduced in Mo-MDSCs lacking p16 and p21

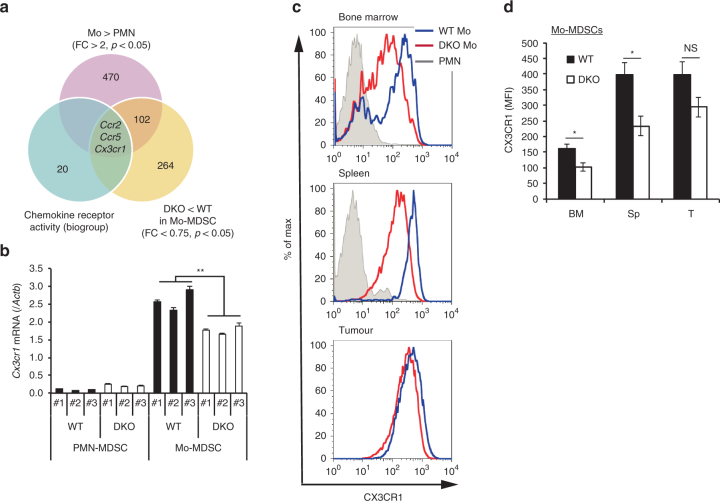

We next sought to identify the mechanism underlying the inability of Mo-MDSCs to infiltrate tumour allografts in p16/p21-DKO mice. Chemotaxis is important for immune cell localisation; MDSC migration into tumours, which is dependent on chemokine receptors, affects tumour progression. We therefore attempted to identify chemokine receptors that were highly expressed in Mo-MDSCs but not in PMN-MDSCs, and that were additionally downregulated in p16/p21-DKO mice relative to WT mice. Ccr2, Ccr5 and Cx3cr1 were identified by RNA-sequencing analysis, and the differences in their expression levels were validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Flow cytometry analysis confirmed that CX3CR1 and CCR2, but not CCR5, were downregulated in splenic Mo-MDSCs lacking both p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1 (Fig. 3c, d; Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). CX3CR1 was also downregulated in the BM Mo-MDSCs lacking both p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1, where progenitor cells differentiate into MDSCs and MDSCs undergo expansion (Fig. 3c, d). However, a significant difference in CX3CR1 expression in intratumour Mo-MDSCs between WT and p16/p21-DKO was not observed (Fig. 3c, d), although the number of intratumoural Mo-MDSCs in p16/p21-DKO mice was much smaller compared to WT mice, suggesting that CX3CR1 highly expressing Mo-MDSCs are concentrated in tumour site, regardless of the p16 Ink4a and p21 Cip1/Waf1 gene status. This finding suggests that the inefficiency of Mo-MDSCs to infiltrate tumour allografts in p16/p21-DKO mice is likely attributable to the reduction of CX3CR1 expression in these mice.

Fig. 3.

CX3CR1 expression is decreased in Mo-MDSCs in p16/p21-DKO mice. a Identification of the factor regulating p16/p21-dependent Mo-MDSC accumulation using RNA-sequencing data analysis; the Venn diagram shows the numbers of genes overexpressed in Mo-MDSCs compared with those in PMN-MDSCs (fold change >2, p < 0.05) and downregulated in DKO Mo-MDSCs compared with WT Mo-MDSCs (fold change <0.75, p < 0.05) categorised under chemokine receptor activity (biogroup). b Cx3cr1 mRNA expression in PMN- and Mo-MDSCs from WT or p16/p21-DKO mice (n = 3), as determined by qRT-PCR. c Representative flow cytometry histograms showing CX3CR1 expression in PMN- and Mo-MDSCs in BM (left), spleen (middle), and tumour (right) from WT and p16/p21-DKO mice 3 weeks after SCT cell injection. d Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CX3CR1 expression in Mo-MDSCs shown in c (n = 5); data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01; NS not significant

CX3CL1+ tumours exhibit p16 and p21-dependent tumour growth

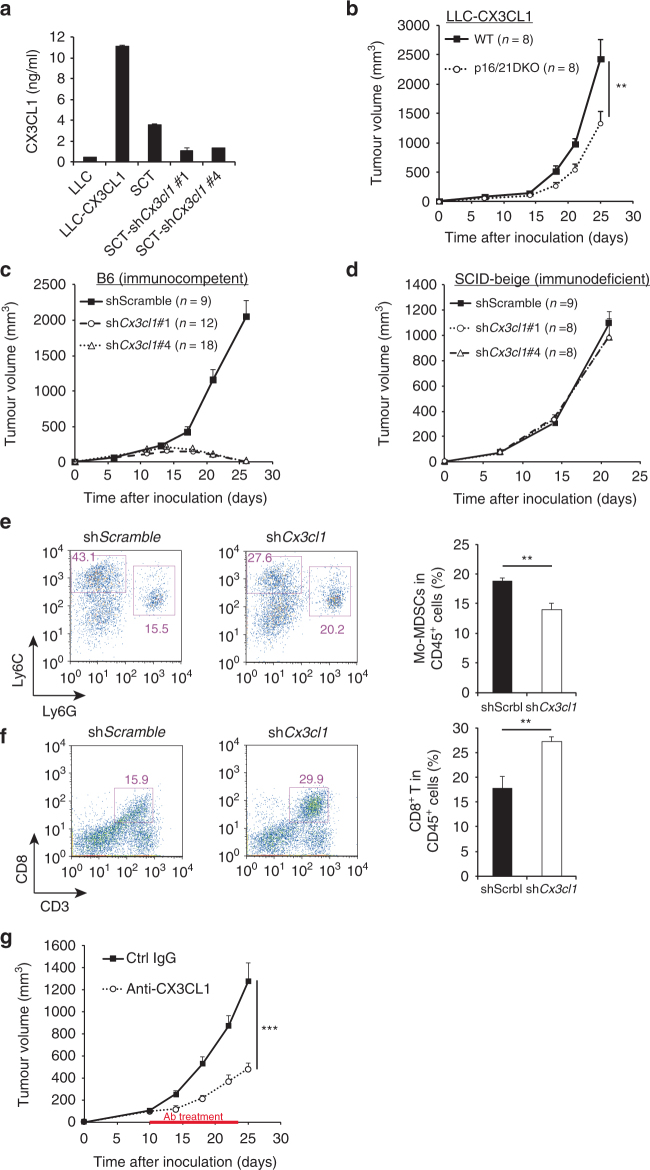

To confirm the role of reduced CX3CR1 expression in the failure of Mo-MDSC infiltration into tumour allografts, we next assessed whether our findings were reproducible in other syngeneic tumour cell lines. Unexpectedly, LLC cells showed no differences in tumour growth between WT and p16/p21-DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Notably, however, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression level of CX3CL1 (also known as fractalkine), the sole CX3CR1 ligand, was much smaller in LLC cells than in SCTs (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 6b). On the other hand, the CCR2 ligands CCL2 and CCL7 were more highly expressed in LLC cells than in SCTs (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). These results suggest that the tumour-suppressive effect of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 is likely dependent on the levels of CX3CL1 expression in tumour cells.

Fig. 4.

CX3CL1 expression in tumour cells is associated with p16/p21-dependent tumour progression. a Amount of soluble CX3CL1 in the indicated conditioned medium, as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data were normalised to cell number. SCT cells were retrovirally transduced to express shRNA targeting Cx3cl1 or a scrambled control shRNA. LLC-CX3CL1 indicates Cx3cl1-transduced LLC cells. b The growth curve of CX3CL1-overexpressing LLC cells in WT and p16/p21-DKO mice. c, d Tumour size in WT (c) and SCID-beige (d) mice injected with SCT-shScramble, SCT-shCx3cl1#1 and SCT-shCx3cl1#4. e, f Representative flow cytometry plots of CD45+CD11b+-gated (e) and CD45+-gated (f) cells in tumours from WT mice 2 weeks after inoculation with Cx3cl1-knockdown or control SCT cells. Cells were labelled with CD45, CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G (e) and CD45 and CD8 (f) antibodies. Graphs indicate CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G− (Mo-MDSC) (e) and CD3+CD8+ (CD8+ T cell) populations (f) among CD45+ cells. g SCT growth curve in WT mice intraperitoneally injected every other day with anti-CX3CL1 antibody (4 µg per mouse) or isotype control rat IgG (4 µg per mouse) from day 10 to 23; data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001; NS not significant

Furthermore, slower growth of LLC tumour allografts in p16/p21-DKO mice was observed when CX3CL1 was ectopically expressed in LLC cells (Fig. 4a, b). Conversely, shRNA-mediated depletion of Cx3cl1 in SCT cells significantly reduced tumour growth in WT syngeneic immunocompetent mice (Fig. 4a, c), but not in immunodeficient mice (Fig. 4d). As expected, the population of intratumoural Mo-MDSCs was reduced, whereas that of intratumoural CD8+ T cells was increased by Cx3cl1 knockdown relative to control SCTs (Fig. 4e, f). Consistently, CX3CL1 neutralisation antibody suppressed tumour progression (Fig. 4g), indicating that the CX3CL1–CX3CR1 pathway represents a potential therapeutic target. These data indicate that tumour growth acceleration induced by p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 is dependent on the CX3CL1–CX3CR1 pathway in tumours. It was previously reported that CX3CR1–CX3CR1 pathway regulates myeloid cell survival by inhibition of pro-apoptotic signals41; therefore, we analysed the apoptosis of Mo-MDSCs. However, there was no difference in the expression levels of the apoptotic inhibitory factor Bcl2 between WT and DKO Mo-MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The ratio of apoptotic Mo-MDSCs in spleen or tumour was similar between WT and DKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Thus attraction rather than survival of CX3CL1-dependent Mo-MDSCs is essential for immunosuppression and consequent SCT progression in vivo.

IFN-γ enhances Mo-MDSC differentiation from BM cells

We next examined the mechanisms underlying the effect of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 on Cx3cr1 expression in Mo-MDSCs. Purified Mo-MDSCs are unstable and rapidly differentiate into various myeloid cell types16; therefore, a stable Mo-MDSC culture was required for this step. MDSCs reportedly differentiate from BM cells in vitro by culturing in medium containing IL-6 and GM-CSF42; however, this method mainly induces differentiation into PMN-MDSCs but not Mo-MDSCs. It has been shown that the IFN-γ–STAT1 axis has an important role in the immunosuppressive ability of Mo-MDSCs15,43. Therefore, we tested whether IFN-γ is involved in the differentiation of MDSCs, especially into Mo-MDSCs. Flow cytometry analysis revealed a greater number of Mo-MDSCs in cultures containing IFN-γ than in those containing GM-CSF and IL-6 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). There were no differences in T cell suppression, the primary function of MDCS, between BM-derived cells cultured in the presence of GM-CSF, IL-6 and IFN-γ, and BM-derived MDSCs induced by GM-CSF with IL-6 (Supplementary Fig. 8b). In addition to Arg1 and Nos2, which are important for the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs, the MDSC marker genes S100a8 and S100a9 44,45 were strongly induced when cells were cultured in GM-CSF, IL-6 and IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig. 8c). On the basis of these results, we concluded that BM cells stimulated with GM-CSF, IL-6 and IFN-γ may be used as BM-derived Mo-MDSCs (BM-Mo-MDSCs).

p16 and p21 regulate Cx3cr1 expression via SMAD3 signalling

To obtain insights into the mechanisms by which p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 regulate Cx3cr1 expression in Mo-MDSCs, BM-Mo-MDSCs were treated with the pan-CDK inhibitor flavopiridol46,47 or the pan-E2F inhibitor HLM006474 (HLM)48 (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, flavopiridol, but not HLM, increased Cx3cr1 expression (Fig. 5b), suggesting that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 regulate Cx3cr1 expression through the CDK, but not the E2F, pathway. Furthermore, although CDK4/6-specific inhibitors, LY283521949 and PD 033299150 have little effect on Cx3cr1 expression, CDK2-specific inhibitors, NU602751 and K0386152, induce Cx3cr1 expression in BM-Mo-MDSCs (Fig. 5c). Consistent with cell cycle distribution of Mo-MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 1a, upper), CDK kinase assay revealed that CDK2 activity of Mo-MDSCs in BM is higher than those in splenic or intratumour Mo-MDSCs, but a certain level of CDK2 activity was still existing in splenic Mo-MDSCs in WT mice and its activity was increased when p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 genes were deleted (Fig. 5d).

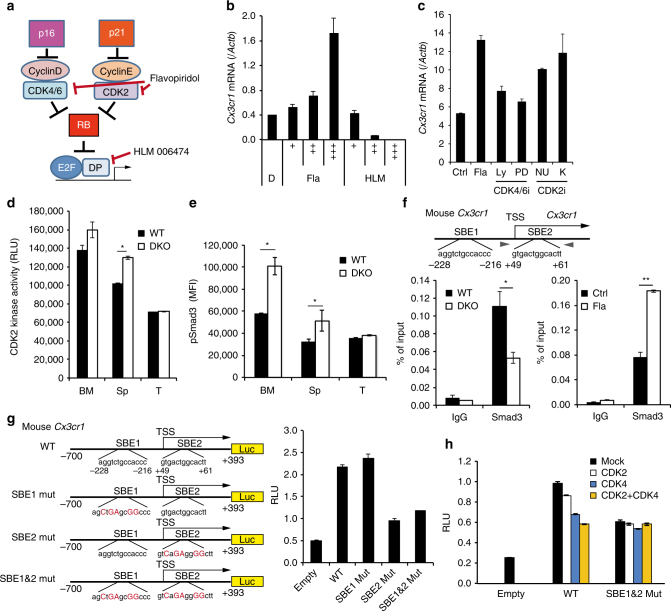

Fig. 5.

CDK-mediated SMAD3 phosphorylation inhibits Cx3cr1 expression. a Diagram of the CDKI-CDK-RB-E2F pathway and sites of action of chemical inhibitors. b Expression of Cx3cr1 mRNA in BM-Mo-MDSCs treated with indicated doses of flavopiridol (Fla), HLM006474 (HLM) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control (D). b “+” indicates drug concentration: Fla; + (4 nM), ++ (20 nM), +++ (100 nM). HLM; + (2 nM), ++ (10 nM), +++ (50 nM). c Expression of Cx3cr1 mRNA in BM-Mo-MDSCs treated with flavopiridol (Fla; 50 nM), LY2835219 (Ly; 5 nM), PD 0332991 (PD; 5 nM), NU6027 (NU; 5 μM), K03861 (K; 250 nM) or DMSO (Ctrl). d Kinase activity of CDK2 against recombinant SMAD3. CDK2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of Mo-MDSCs purified from bone marrow (BM), spleen (Sp) and tumour (T). e Flow cytometric analysis of phosphorylated Smad3 (S213). Graphs indicate mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of indicated protein expression in Mo-MDSCs (n = 4). f Smad3 binding to the Cx3cr1 promoter region was evaluated by ChIP. Lysates were prepared from BM-Mo-MDSCs derived from WT or p16/p21-DKO mice (left). WT BM-Mo-MDSCs were treated with 100 nM flavopiridol (Fla) for 24 h (right). Two SBEs are located around the transcriptional start site (TSS) of the mouse Cx3cr1 gene. Arrowheads indicate primer positions. g, h Schematic representation of mouse Cx3cr1 promoter reporter constructs; two SBEs (SBE1 and SBE2) are shown in the sequence, and mutation sites are indicated by red uppercase letters. THP-1 cells were transfected with the indicated reporter plasmids and pCMV-Renilla (g). Where indicated, cells were also co-transfected with expression plasmids encoding CDK2, CDK4 or both (h). At 48 h after transfection, the luciferase activities were measured. Data are representative of three biological replicates and presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01

We next attempted to identify the transcription factors that regulate Cx3cr1 expression under the control of CDK activity in Mo-MDSCs. Substantial reduction of tumour growth was observed in p16/p21-DKO mice but not in mice lacking either p16 Ink4a or p21 Cip1/Waf1 (single KO mice) (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 2), suggesting that both CDK2 and CDK4 associate with this transcription factor in a complementary fashion. On the basis of this assumption, we identified SMAD3 as a candidate transcription factor using the STRING database (http://string-db.org). It has been reported that phosphorylation of the SMAD3 linker region by CDK2 and CDK4 inhibits SMAD3 transcriptional activity53–55. Indeed, the linker phosphorylation (Ser-213) in SMAD3 was increased in BM and splenic Mo-MDSCs from p16/p21-DKO mice compared with those from WT mice (Fig. 5e). Notably, the levels of CX3CR1 expression were inversely correlated with those of phosphorylated SMAD3 (Figs. 3c and 5e). These data suggest that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 have important roles in controlling CX3CR1 expression for the property of chemotaxis in Mo-MDSCs, by tuning CDK2 activity during their maturation.

We next confirmed whether the change of linker phosphorylation level in SMAD3 affects Cx3cr1 expression directly. Two SMAD-binding elements, SBE1 and SBE2, were present in the Cx3cr1 promoter region. A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showed that SMAD3 binding to SBE2 was downregulated in p16/p21-DKO and upregulated by treatment with a CDK inhibitor (Fig. 5f). SMAD3 activation then stimulated Cx3cr1 promoter activity via binding to SBE2 (Fig. 5g) and ectopic expression of CDK2 inhibited SBE-mediated Cx3cr1 promoter activity (Fig. 5h). Together, these data strongly suggest that inactivation of CDK2 induce Cx3cr1 expression via SMAD3 activation.

Flavopiridol enhances SCT growth in vivo

CDK inhibitors such as flavopiridol, which is used to treat leukaemia46, have attracted recent attention as a result of their potential as anticancer agents. However, the present results suggest that CDK inhibition may accelerate tumour growth by enhancing Mo-MDSC infiltration into tumours expressing CX3CL1 in vivo. To explore this possibility, we generated SCT cells expressing SV40 large T antigen (SCT-LT), in which the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor (Rb)-pathway is inactivated, to elicit resistance against CDK inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). The growth of SCT-LT was substantially increased in mice treated with flavopiridol, accompanied by enhanced CX3CR1 expression in Mo-MDSCs and increased accumulation of Mo-MDSCs in tumours (Fig. 6a–e). These data, in conjunction with the notion that a certain proportion of human cancers contains disruption of the Rb-pathway, strongly suggest that treatment with CDK inhibition may promote tumour development, depending on the level of expression of CX3CL1 and the Rb status in the tumour.

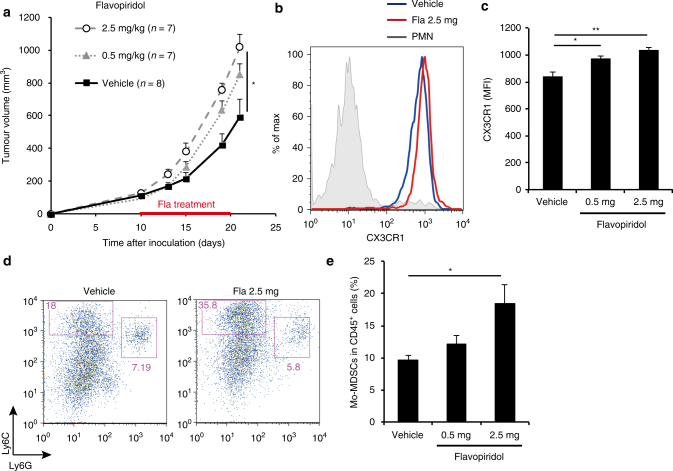

Fig. 6.

Flavopiridol accelerates tumour growth in vivo. a SCT growth curve in WT mice administered flavopiridol (2.5 or 0.5 mg/kg) or vehicle (control) once daily, from day 10 to day 20. b Representative flow cytometry histograms showing CX3CR1 expression in splenic Mo-MDSCs from WT mice 10 days after flavopiridol administration. c Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CX3CR1 expression shown in b (n = 4). d Representative flow cytometry plots of CD45+CD11b+-gated cells in tumours from WT mice after flavopiridol administration; cells were labelled with CD45, CD11b, Ly6C and Ly6G antibodies. e Fraction of CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G− cells among CD45+-gated cells shown in d (n = 5). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present work is the first to report that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 CDK inhibitors, which are considered cell-intrinsic tumour suppressors, in fact promote tumour development, as demonstrated in the present allograft mouse model. Both p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 are expressed in Mo-MDSCs and facilitate infiltration of Mo-MDSC into the tumour microenvironment by upregulating CX3CR1 expression and conferring resistance to anti-tumour immune mechanisms (Figs. 1–5; Supplementary Fig. 10a). Notable, moreover, administration of flavopiridol was found to accelerate the development of orthotopically transplanted SCT-LT cells in syngeneic mice (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 10b). These results, together with previous reports showing that high p16INK4A expression in the tumour stroma was strongly associated with high risk of recurrence56 or poor survival57 in some types of cancer, suggest that there might be the negative side effects of CDK inhibitor drugs used for cancer treatment.

Regarding the role of p16Ink4a in myeloid cells, it is known to promote M1 polarisation, which reflects an inflammatory state for macrophages58. Indeed, the present study also showed Arg1 upregulation in p16/p21-DKO Mo-MDSCs (Supplementary Fig. 3d). It is generally believed that M2 skewing promotes tumour growth. Therefore, it is most likely that the decreased tumour growth in p16/p21-DKO mice is caused by MDSC alteration rather than defective macrophage polarisation.

Although the role of CDK2 and CDK4 (CDK2/4) in cell cycle control is well established, there is increasing evidence that CDK2/4 also have cell-cycle independent roles in various non-proliferating cells55. In the present study, we revealed a novel function of CDK2 in regulating CX3CR1 expression via phosphorylation and inactivation of SMAD3 in Mo-MDSCs (Fig. 5). On the basis of our comparative data of MDSCs in bone marrow, in spleen and in tumour, we propose a possible scenario whereby p16/p21 regulates Mo-MDSCs function during their maturation. Once Mo-MDSCs leave BM, they start to mature, terminate its proliferation and exert their own character, for example chemotaxis and immunosuppression. During this maturation process, CDK2 activity is sustained, yet not enough to drive cell cycle, and tuned by p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 to lead the expression of CX3CR1 for chemotaxis (Supplementary Fig. 1a; Figs. 3c, d and 5d, e).

The chemotaxis of immune cells contributes to important aspects of the tumour microenvironment59; in particular, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors as therapeutic agents, which has achieved significant results in cancer therapy, has revealed the importance of tumour-infiltrating immune cells for predicting the response to checkpoint blockade60,61. Note that the absence of CX3CL1 expression in pre-treatment tumours60 is reportedly correlated with the response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody. We speculate that high CX3CL1 expression might recruit Mo-MDSCs to tumour, thereby increasing PD-L1-independent immunosuppression. However, the role of the CX3CL1–CX3CR1 axis in anti-tumour immunity is highly controversial. For instance, the correlation between CX3CL1 expression and the poor prognosis of cancer patients varies depending on the type of cancer: in colorectal cancer and gastric adenocarcinomas, high CX3CL1 expression is associated with better prognosis62,63; however, the opposite outcome is observed in breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma64,65. Using SCT cells, which are derived from the skin of p16 Ink4a knockout mice and are highly expressing CX3CL1, we showed that treatment with anti-CX3CL1 exerted significant suppressive effects against tumour progression, which has not been previously demonstrated in vivo (Fig. 4g). We therefore suggest that CX3CL1 represents a novel molecular target for cancer therapy, especially in combination with CDK inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 10b).

In tumour microenvironment, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and pre-cancerous cells are shown to exhibit senescence-like phenotypes including SASPs. For example, it was recently reported that some CAFs and pre-cancerous hepatocytes recruit MDSCs via IL-6 and CCL2-mediated pathway, respectively, thereby protecting cancer cells from immune cells66,67. These results, together with our findings that p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 enhance Mo-MDSC chemotaxis, led us to speculate that the formation of the tumour microenvironment may have a synergistic effect on protumoural MDSC recruitment

The role of p16Ink4a in the development of cellular senescence is well known; furthermore, p16Ink4a has been the most widely accepted marker for senescent cells for over two decades1,11,12,68. Notably, moreover, a recent study reported that elimination of p16Ink4a-expressing senescent cells from mice prolonged lifespan and alleviated ageing related diseases including cancer69, indicating that the elimination of senescent cells would be beneficial for homoeostasis, especially in aged animals. However, because MDSCs express high levels of p16Ink4a without any noticeable senescent phenotype, the results of eliminating p16Ink4a expressing cells must be interpreted with caution, as previously suggested by Baker et al.

In summary, our results reveal a novel function of p16Ink4a and p21Cip1/Waf1 CDK inhibitors in MDSCs, thus expanding our understanding of the mechanisms by which the chemotaxis of MDSCs is regulated. A greater understanding of the molecular mechanisms linking these CDK inhibitors to the chemotaxis of immune cells should therefore provide valuable novel strategies to control tumorigenesis.

Methods

Mice

WT C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan and CLEA Japan. SCID-Beige (CB17.Cg-PrkdcscidLystbg-J/CrlCrlj) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories Japan. p16/p21-DKO mice were generated as previously reported9. p16-luc mice11 and p21-luc mice10 were generated as previously reported and backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for at least 8 generations. All animals were maintained according to protocols approved by the Committee for the Use and Care of Experimental Animals of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (Tokyo, Japan) and the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University (Osaka, Japan).

Cell culture and tumour inoculation

The SCT line was prepared from a DMBA- and TPA-treated p16 KO mouse9. LLC (RCB0558) cell was provided by RIKEN BioResource Center through the National BioResource Project of MEXT, Japan. SCT and LLC cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (08458–45; Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). All cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2. For injection, cultured cells were collected in logarithmic growth phase (40–70% confluence). Mice (12- to 20-weeks-old) were anaesthetised with pentobarbital, and their flanks were subcutaneously injected with the following cells: SCT (1 × 106), LLC (1 × 105), SCT-LT (1 × 106), LLC-CX3CL1 (1 × 105) or SCT-shCx3cl1 (1 × 106). All cell lines were resuspended in 50% Matrigel (Corning). It was confirmed that cell lines had no mycoplasma contamination before inoculation into mice. Measurements of tumour volume were a performed in blinded set-up.

Bioluminescence imaging

Isoflurane-anaesthetised mice were intraperitoneally injected with 75 mg/kg d-luciferin substrate (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) (30 mg/ml in saline) and imaged using an IVIS Lumina system (Caliper Life Sciences). Luminescence was determined to begin 5 min after substrate administration. Female p16-Luc mice were subcutaneously injected in the footpad with LLC (2.5 × 105) or SCT (1 × 106) cells. After 3 weeks (LLC) or 10 weeks (SCT), tumour-bearing mice were subjected to bioluminescence imaging. p21-Luc mice were subcutaneously injected on the dorsal side with LLC (4 × 105 cells) or SCT (1 × 106 cells). After 2 weeks (LLC) or 3 weeks (SCT), the mice were subjected to bioluminescence imaging.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue specimens were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections of 5-µm thickness were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque) for 30 min, blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS, and stained with the antibodies listed in Supplementary Data 4. Non-specific labelling of Fc receptors was prevented by incubating the cells with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (1:500, 93; BioLegend).

MDSC isolation

PMN-MDSCs (Ly6G+) and Mo-MDSCs (Ly6G−Gr-1+) were isolated from the BMs, spleens, or tumours of SCT-bearing mice 3 weeks after injection, using the Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Isolation kit for mice (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with all steps performed at 4 °C. The purity of MDSC subfractions was typically higher than 95%.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

For analysis of gene expression, total RNA was extracted using the mirVana RNA Isolation kit (Ambion/Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cDNA was synthesised using the PrimeScript RT Reagent kit (Takara Bio). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara Bio) on a Prism 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems). Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell suspensions were prepared from spleen or lymph node tissue by sieving and gentle pipetting. To prepare intratumoural cell suspensions, minced tumours were agitated in Hank’s balanced salt solution containing 1 mg/ml collagenase IV, 100 µg/ml hyaluronidase and 2 U/ml DNAse IV (Sigma-Aldrich) at 20–25 °C for 2 h, and strained through a 70-µm mesh (Greiner Bio-One). Non-specific labelling of Fc receptors was prevented by incubating the cells with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (1:500, 93; BioLegend). Intracellular staining of FoxP3 and intranuclear staining were performed with the FOXP3 Fix/Perm Buffer Set (BioLegend) and True-Nuclear Transcription Factor Buffer Set (BioLegend), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Data 4. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSAria instrument with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) or Attune NxT (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and data were analysed with FlowJo v9 or v10 software (Tree Star).

Cell cycle analysis

For flow cytometry-based cell cycle analysis, cells were labelled with antibodies against cell surface antigens, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque) for 15 min, and incubated in 10 µg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dojindo)/0.1% Triton X-100 (Nacalai Tesque) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at 20–25 °C.

Proliferation assay

For the in vitro proliferation assay, purified splenic Mo-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs and T cells were stained with 5 µM carboxyfluoroscein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; eBioscience/Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Overall, 1 × 105/ml CFSE-labelled Mo- and PMN-MDSCs are cultured in 10% FBS-containing Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)1640 medium (30264–85; Nacalai Tesque) supplemented with 20 ng/ml mouse GM-CSF (Peprotech) for 48 h. Dividing cells were identified as those showing diluted CFSE signals relative to unstimulated T cells. For the in vivo 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay, purified Mo-MDSCs, PMN-MDSCs and T cells were stained with 5 µM CFSE. SCT-bearing mice were given drinking water containing 1 mg/ml EdU (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 72 h just after CFSE-labelled cell injection (1 × 106/mouse)70. EdU incorporation was detected using a Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The proliferation rate was calculated as the number of EdU-positive cells among CFSE-positive cells.

Senolytic drug treatment and apoptosis assay

For in vitro experiments, young mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were cultured in 3% O2. Senescent MEFs were prepared by treatment with 15 ng/ml doxorubicin hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) in 20% O2 for 7 days. Cells were treated with ABT-263 (LKT Laboratories, Inc.) for 72 h. GM-CSF, IL-6 and IFN-γ (Peprotech) were added to the culture medium during treatment of BM-Mo-MDSCs with ABT-263. Apoptotic cell staining was performed with the PE Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit with 7-AAD (BioLegend), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Apoptotic cells were detected by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). For in vivo experiments, wild-type mice were treated with control vehicle (10% ethanol, 30% polyethylene glycol 400 and 60% Phosal 50 PG; Phospholipid Gmbh), or 50 mg/kg/d ABT-263 from day 21 to day 27 after SCT inoculation. At day 28, peripheral blood was collected and stained for Mo-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6ChighLy6G−) and PMN-MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6CintLy6G+) among CD45+ cells.

T-cell proliferation suppression assay

The antigen-dependent T cell activation assay29 was performed to assess antigen-dependent T-cell suppression. DC2.4 dendritic cells and RF33.70 OVA-SIINFEKL specific T-T hybridoma cells were provided by K. L. Rock (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA)27,28. Briefly, 1 × 103 DC2.4 cells were cultured overnight in a 96-well plate and then incubated with OVA-SIINFEKL peptide (MBL International) for 24 h. OVA-pulsed cells were treated with 10 µg/ml mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min and washed twice with PBS. DC2.4 cells were co-cultured with 1 × 104 RF33.70 cells and purified splenic PMN- or Mo-MDSCs (1 × 104, 5 × 103, 2.5 × 103 or 1.25 × 103 cells) for 20 h. The amount of IL-2 released into the culture medium was measured with a murine IL-2 Mini TMB ELISA Development Kit (Peprotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Antigen-independent T cell receptor stimulation was performed as follows: T cells were isolated from the spleens of WT C57/BL6J mice 3 weeks after injection using the Pan-T Cell Isolation Kit II for mouse (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated T cells were stained with 5 µM CFSE. CFSE-labelled T cells were stimulated with Dynabeads Mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Veritas Life Science) and co-cultured with purified splenic Mo-MDSCs in 96-well round-bottomed plates (BM Equipment). After 4 days, cells were labelled with antibodies against CD4 or CD8 (BioLegend), and the CFSE signal from live CD4+- or CD8+-gated cells was analysed by flow cytometry. Dividing cells were identified as those showing diluted CFSE signals relative to unstimulated T cells.

Adoptive cell transfer

PMN- and Mo-MDSCs were purified from the spleens of SCT-bearing WT and p16/p21-DKO mice 3 weeks after SCT injection. For intravenous transfer, 8- to 10-week-old WT C57BL/6 J mice were subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106 SCT cells in Matrigel (Corning), followed by injection of 2 × 106 PMN- or Mo-MDSCs into the tail vein. For subcutaneous transfer, 10-week-old WT C57BL/6J mice were subcutaneously injected with a mixture of 1 × 106 SCTs and 2 × 106 Mo-MDSCs in 50% Matrigel. For observation of injected Mo-MDSCs, 2 × 106 Mo-MDSCs were stained with 2 µM CFSE and then injected intravenously or subcutaneously.

RNA-sequencing

PMN- and Mo-MDSCs were purified from the spleens of SCT-bearing WT and p16/p21-DKO mice. RNA isolation was performed using the mirVana RNA Isolation kit. Library preparation was performed using a TruSeq stranded mRNA sample prep kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform in a 75-base single-end mode. Illumina Casava1.8.2 software was used for base calling. Sequenced reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome sequences (mm10) using TopHat v2.0.13 in combination with Bowtie2 ver. 2.2.3 and SAMtools ver. 0.1.19. The fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKMs) were calculated using Cuffnorm version 2.2.1.

Viral infection and establishment of stable cell lines

LLC and SCT cells were infected with retrovirus encoding mouse Cx3cl1 (in pMarX-puro) and mouse Cx3cl1 shRNA (in pRetrosuper-puro) or SV40LT antigen (in pMarX-puro), respectively. Infected cells were selected in 5 µg/ml puromycin-containing medium for 7 days, and the selected cells were maintained in medium containing 1 µg/ml puromycin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries).

In vivo drug administration

For anti-CX3CL1 experiments, mice were administered either anti-CX3CL1 rat IgG (MAB571; R&D Systems) or isotype anti-rat IgG (MAB006; R&D Systems) (4 µg/mouse by intraperitoneal injection) once daily for 14 days starting on day 10 post-SCT inoculation. For CDK inhibition, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injections of flavopiridol HCl (Selleckchem) (2.5 or 0.5 mg/kg/day) or 1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) in PBS as a vehicle control for 11 days starting on day 10 post-SCT-LT inoculation.

BM-Mo-MDSC preparation

The protocol for BM-Mo-MDSC preparation was modified from that used in a previous report. Femurs were removed from C57BL/6 mice and the BM was flushed. Red blood cells were lysed with ammonium chloride. BM cells were adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 106/ml in 10% FBS-containing RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 20 ng/ml mouse GM-CSF, 40 ng/ml mouse IL-6 and 2 ng/ml mouse IFN-γ (Peprotech). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2- and 3% O2-humidified atmosphere for 4–5 days. Non-adherent and loosely adherent cells were collected by gentle pipetting. In some experiments, BM-Mo-MDSCs were treated with flavopiridol HCl (Selleckchem) or HLM (Tocris Bioscience) along with GM-CSF, IL-6, and IFN-γ on day 4, and collected 24 h later.

In vitro kinase assay

One million Mo-MDSCs purified from bone marrow, spleen and tumour were lysed by cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology), and immunoprecipitated by anti-CDK2, and Protein A Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The antibodies are listed in Supplementary Data 4. For kinase reaction, precipitated CDK2 was incubated in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5) containing 5 ng/µl of recombinant SMAD3 (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µM ATP (Promega), 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 1 mM DTT and 40 mM MgCl2 at 30 °C for 2 h. ATP to ADP conversion during kinase reaction was measured by ADP-Glo Kinase Assay (Promega) and Powerscan HT (DS Pharma Biomedical).

ChIP analysis

ChIP analysis was performed using EZ-ChIP (Millipore), Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and anti-Smad3 antibody (Abcam) or normal rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) as a negative control. Information on the antibodies used may be found in Supplementary Data 4. Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by qRT-PCR. For information on primers used, see Supplementary Data 3.

Luciferase reporter assay

The mouse Cx3cr1 gene promoter region (from −700 to +397) was amplified from the genome of a C57BL/6J mouse. PCR mutagenesis for 2 SBEs was performed using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 3. The amplified fragments were inserted into the pGL3basic vector (Promega). cDNAs for human CDK2 and CDK4 were obtained by PCR and subcloned into the pcDNA3. THP-1 (JCRB0112.1) cells were provided by RIKEN BioResource Center through the National BioResource Project of MEXT, Japan and cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 100 µM sodium pyruvate (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). THP-1 cells were transfected with plasmids, using Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V and Nucleofector I Device (Lonza); 48 h later, luciferase activity was measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reporter activity was normalised to that of Renilla luciferase derived from the co-transfected pCMV-Renilla vector. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in Laemmli’s sample buffer. The samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies and appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish-peroxidase. Bound antibodies were visualised by chemiluminescence following incubation with Chemi-Lumi One L HRP Substrate (Nacalai Tesque) or Amersham ECL Prime (GE Healthcare). For information on the antibodies used, see Supplementary Data 4.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test (two-tailed) was performed to evaluate the significance of differences between two groups.

Data availability

RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO GSE93359). All other remaining data are available within the article and supplementary files, or available from the authors upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the NGS core facility of the Genome Information Research Center at the Research Institute for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University for support with RNA-sequencing and data analysis. We thank K. Rock (University of Massachusetts Medical School) and M. Ito (The Jikei University School of Medicine) for providing RF33.70 and DC2.4 cells. We also thank the members of the Hara laboratory for helpful discussion during the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP16K19064 and JP14J10280 and 26250028, and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED).

Author contributions

E.H., S.W. and A.O. conceptualised the study, designed the experiments and wrote the paper. A.O. executed the experiments and analysed the data. A.K. contributed to the adoptive transfer experiments and the drug administration in vivo.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-017-02281-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Atsushi Okuma, Email: aokuma@biken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

Eiji Hara, Email: ehara@biken.osaka-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Hara E, et al. Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:859–867. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noda A, Ning Y, Venable SF, Pereira-Smith OM, Smith JR. Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp. Cell Res. 1994;211:90–98. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams PD. Healing and hurting: molecular mechanisms, functions, and pathologies of cellular senescence. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperka T, Wang J, Rudolph KL. DNA damage checkpoints in stem cells, ageing and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:579–590. doi: 10.1038/nrm3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krimpenfort P, Quon KC, Mooi WJ, Loonstra A, Berns A. Loss of p16Ink4a confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:83–86. doi: 10.1038/35092584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Caballero J, Flores JM, Garcia-Palencia P, Serrano M. Tumor susceptibility of p21(Waf1/Cip1)-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6234–6238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharpless NE, et al. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature. 2001;413:86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi S, et al. Intrinsic cooperation between p16INK4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 in the onset of cellular senescence and tumor suppression in vivo. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9381–9390. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtani N, et al. Visualizing the dynamics of p21(Waf1/Cip1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor expression in living animals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15034–15039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706949104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamakoshi K, et al. Real-time in vivo imaging of p16Ink4a reveals cross talk with p53. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:393–p407. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burd CE, et al. Monitoring tumorigenesis and senescence in vivo with ap16(INK4a)-luciferase model. Cell. 2013;152:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:739–752. doi: 10.1038/nrc3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Movahedi K, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–4244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 2008;181:5791–5802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lesokhin AM, et al. Monocytic CCR2(+) myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote immune escape by limiting activated CD8 T-cell infiltration into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:876–886. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao W, et al. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma express chemokines and chemokine receptors differentially. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;26:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Highfill SL, et al. Disruption of CXCR2-mediated MDSC tumor trafficking enhances anti-PD1 efficacy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:237ra267. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronte V, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12150. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronte V, et al. Identification of a CD11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/CD31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8(+) T cells. Blood. 2000;96:3838–3846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zea AH, et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3044–3048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youn JI, et al. Epigenetic silencing of retinoblastoma gene regulates pathologic differentiation of myeloid cells in cancer. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:211–220. doi: 10.1038/ni.2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimi T, et al. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2579–2593. doi: 10.1101/gad.179515.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coppe JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, Campisi J. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang J, et al. Clearance of senescent cells by ABT263 rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Nat. Med. 2016;22:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Z, Reznikoff G, Dranoff G, Rock KL. Cloned dendritic cells can present exogenous antigens on both MHC class I and class II molecules. J. Immunol. 1997;158:2723–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant EP, Rock KL. MHC class I-restricted presentation of exogenous antigen by thymic antigen-presenting cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 1992;148:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito M, et al. Combinatorial contextualization of peptidic epitopes for enhanced cellular immunity. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e110425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronte V, et al. IL-4-induced arginase 1 suppresses alloreactive T cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 2003;170:270–278. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzoni A, et al. Myeloid suppressor lines inhibit T cell responses by an NO-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 2002;168:689–695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Mitri D, et al. Tumour-infiltrating Gr-1+ myeloid cells antagonize senescence in cancer. Nature. 2014;515:134–137. doi: 10.1038/nature13638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noman MZ, et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1alpha, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:781–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kujawski M, et al. Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:3367–3377. doi: 10.1172/JCI35213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toh B, et al. Mesenchymal transition and dissemination of cancer cells is driven by myeloid-derived suppressor cells infiltrating the primary tumor. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolcetti L, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang B, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–1131. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serafini P, Mgebroff S, Noonan K, Borrello I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote cross-tolerance in B-cell lymphoma by expanding regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5439–5449. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:486–499. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlecker E, et al. Tumor-infiltrating monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells mediate CCR5-dependent recruitment of regulatory T cells favoring tumor growth. J. Immunol. 2012;189:5602–5611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landsman L, et al. CX3CR1 is required for monocyte homeostasis and atherogenesis by promoting cell survival. Blood. 2009;113:963–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marigo I, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medina-Echeverz J, et al. IFN-gamma regulates survival and function of tumor-induced CD11b+Gr-1high myeloid derived suppressor cells by modulating the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl2a1. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:2457–2467. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng P, et al. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2235–2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin H, et al. Generation of a new therapeutic peptide that depletes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Nat. Med. 2014;20:676–681. doi: 10.1038/nm.3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arguello F, et al. Flavopiridol induces apoptosis of normal lymphoid cells, causes immunosuppression, and has potent antitumor activity In vivo against human leukemia and lymphoma xenografts. Blood. 1998;91:2482–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlson BA, Dubay MM, Sausville EA, Brizuela L, Worland PJ. Flavopiridol induces G1 arrest with inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 2 and CDK4 in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2973–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sangwan M, et al. Established and new mouse models reveal E2f1 and Cdk2 dependency of retinoblastoma, and expose effective strategies to block tumor initiation. Oncogene. 2012;31:5019–5028. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gelbert LM, et al. Preclinical characterization of the CDK4/6 inhibitor LY2835219: in vivo cell cycle-dependent/independent anti-tumor activities alone/in combination with gemcitabine. Invest. New Drugs. 2014;32:825–837. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fry DW, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 by PD 0332991 and associated antitumor activity in human tumor xenografts. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1427–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arris CE, et al. Identification of novel purine and pyrimidine cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors with distinct molecular interactions and tumor cell growth inhibition profiles. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:2797–2804. doi: 10.1021/jm990628o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander LT, et al. Type II inhibitors targeting CDK2. Acs. Chem. Biol. 2015;10:2116–2125. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuura I, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinases regulate the antiproliferative function of Smads. Nature. 2004;430:226–231. doi: 10.1038/nature02650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarasewicz E, et al. Inhibition of CDK-mediated phosphorylation of Smad3 results in decreased oncogenesis in triple negative breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3191–3201. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.950126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hydbring P, Malumbres M, Sicinski P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:280–292. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Witkiewicz AK, et al. Association of RB/p16-pathway perturbations with DCIS recurrence: dependence on tumor vs. tissue microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang T, et al. Senescent carcinoma-associated fibroblasts upregulate IL8 to enhance prometastatic phenotypes. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:3–14. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cudejko C, et al. p16INK4a deficiency promotes IL-4-induced polarization and inhibits proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. Blood. 2011;118:2556–2566. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roussos ET, Condeelis JS, Patsialou A. Chemotaxis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:573–587. doi: 10.1038/nrc3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herbst RS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tumeh PC, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hyakudomi M, et al. Increased expression of fractalkine is correlated with a better prognosis and an increased number of both CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008;15:1775–1782. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9876-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohta M, et al. The high expression of Fractalkine results in a better prognosis for colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Oncol. 2005;26:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsubara T, Ono T, Yamanoi A, Tachibana M, Nagasue N. Fractalkine-CX3CR1 axis regulates tumor cell cycle and deteriorates prognosis after radical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007;95:241–249. doi: 10.1002/jso.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsang JY, et al. CX3CL1 expression is associated with poor outcome in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;140:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2653-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruhland MK, et al. Stromal senescence establishes an immunosuppressive microenvironment that drives tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11762. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eggert T, et al. Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:533–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krishnamurthy J, et al. Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1299–1307. doi: 10.1172/JCI22475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baker DJ, et al. Naturally occurringp16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature. 2016;530:184–189. doi: 10.1038/nature16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amano SU, et al. Local proliferation of macrophages contributes to obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Cell Metab. 2014;19:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

RNA-sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO GSE93359). All other remaining data are available within the article and supplementary files, or available from the authors upon request.