Abstract

Studies of the fundamental physics and chemistry of colloidal semiconductor nanocrystal quantum dots (QDs) have been central to the field for over 30 years. Although the photophysics of QDs has been intensely studied, much less is understood about the underlying chemical reaction mechanism leading to monomer formation and subsequent QD growth. Here we investigate the reaction mechanism behind CdSe QD synthesis, the most widely studied QD system. Remarkably, we find that it is not necessary for chemical precursors used in the most common synthetic methods to directly react to form QD monomers, but rather they can generate in situ the same highly reactive Cd and Se precursors that were used in some of the original II-VI QD syntheses decades ago, i.e., hydrogen chalcogenide gas and alkyl cadmium. Appreciating this surprising finding may allow for directed manipulation of these reactive intermediates, leading to more controlled syntheses with improved reproducibility.

Little is understood about the chemical evolution of precursors to quantum dots. Here, the authors find that under the high temperature conditions typical of CdSe quantum dot synthesis, precursors decompose into highly reactive species in a critical first step before forming monomers and finally nanocrystals.

Introduction

The thermolytic decomposition of organometallic precursors to form monomers has been the synthetic method of choice for the nucleation of semiconductor nanocrystalline quantum dots (QDs) for decades1–3. Early synthetic methods produced high-quality QDs through the injection of the phosphine-chalcogenide precursor trioctylphosphine selenide (TOPSe) into thermally decomposing dimethylcadmium2. In the past 20 years, synthetic methods have advanced substantially making the colloidal QD synthesis reaction safer, and with greater control over nanoparticle size, shape, and stoichiometry. For example, the highly toxic dimethylcadmium was replaced with cadmium carboxylates4, secondary phosphine chalcogenides allowed for control over QD surface composition5–7, and the use of single-source precursors drove improvements in reaction yields8–10; all have allowed for improved size selectivity and monodispersity. Recent synthetic breakthroughs have focused on designing precursors to better program size and reaction yield11–13.

Contrary to the advances made in developing improved QD synthesis, elucidating the specific chemical reaction pathways taking initial molecular precursors to QDs has been difficult and limited in scope. In an early example, it was shown that the reactive chalcogenide precursor in lead chalcogenide QD syntheses was not the tertiary phosphine-chalcogenide precursor, but actually a secondary phosphine-chalcogenide impurity5. With respect to CdSe QDs, it was proposed that QD molecular precursors (i.e., cadmium oleate and TOPSe) form a transition state given by a Lewis acid-base complex14–16; which forms the CdSe bond after an attack by an alkyl carboxylate14, 16, 17. Noteworthy products from this reaction are trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO) and oleic anhydride14. Further mechanistic studies are motivated by the need to control the kinetics of the reactive precursors in solution and eliminate extraneous reactants, enhance reproducibility, and obtain better overall control over nanoparticle growth17, 18. In addition, new precursors and synthetic methods can be designed with controlled decomposition to yield more highly engineered QDs of desired shapes, sizes, and compositions11.

In the following study, we take a somewhat unique approach to our mechanistic studies by investigating the thermal decomposition of each organometallic precursor separately, but importantly, under the high temperature reaction conditions that are common in CdSe QD syntheses. Specifically, we focus on the chemical reaction mechanism of the most common precursors for making CdSe QDs: the reaction of cadmium carboxylate and tertiary phosphine selenide. We hypothesize that complex reaction intermediates, where both cadmium and selenium precursors remain intact14, 16, 19, 20, are not likely to form given the extreme temperatures necessary for CdSe QD formation thus suggesting an alternate reaction pathway. We find that at under conditions common to CdSe QD syntheses, both the tertiary phosphine-chalcogenide precursor and metal-carboxylate precursor thermally decompose to extremely reactive species: hydrogen selenide and dialkylcadmium, respectively. On the basis of this observation, we propose a mechanism for QD synthesis in which these decomposition products react to form CdSe monomer, which then further react to nucleate nanoparticles3, 21. Importantly, this mechanism includes the formation of the anhydride and the phosphine oxide products observed in previous mechanism studies14, 17, and can explain the relatively low chemical yields observed in the CdSe QD synthesis reactions of this type16.

Results

Thermal decomposition of tri-n-butylphosphine selenide

We studied the decomposition of tri-n-butylphosphine selenide (TnBPSe) in the absence of a cadmium source to model the decomposition of tertiary phosphine selenides under the conditions of typical CdSe QD syntheses. High-quality cadmium chalcogenide QDs are typically synthesized at temperatures between 270 and 350 °C. Thus, tri-n-butylphosphine selenide (TnBPSe), octanoic acid (a shorter chain analog for oleic acid), and tetradecane were combined and heated at 250 °C. We expected significant reactivity in the phosphine selenide, as phosphine chalcogenides are likely to decompose at these temperatures given their reactivity under similar conditions22, 23. In addition, alkyl tertiary phosphine selenide bond dissociation energies are low, making breaking the phosphine-chalcogenide bond accessible, as demonstrated by Ruberu et al. through phosphine crossover experiments at temperatures above 250 °C24–26.

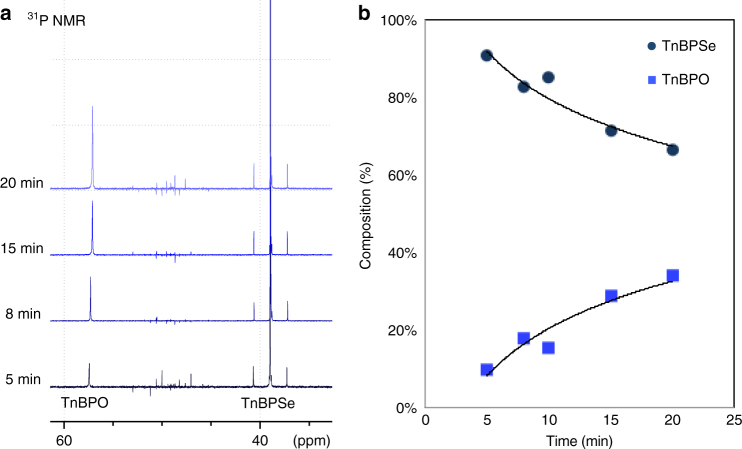

As shown in Fig. 1, analysis of the reaction mixture by31P NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy) showed the formation of tri-n-butylphosphine oxide (TnBPO), a product universally seen in other studies of CdSe QD mechanism with cadmium present14, 27–29, and a clear indication that the TnBPSe had decomposed. The TnBPSe decomposition reaction for the conversion of TnBPSe to TnBPO was further studied at various time points after hot injection by 31P NMR (Fig. 1). The percentage composition of TnBPO after 15 min was calculated to be 30% on average, which is consistent with the reaction yields of CdSe QDs using TnBPSe16. Surprisingly, we were unable to observe any other molecular form of selenium in solution by 77Se or 31P NMR (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Previous mechanistic studies attribute the lack of a Se signal in NMR to formation of CdSe QDs, which would be NMR silent5, 14, 17, 19, 27. However, in the absence of Cd this explanation is not possible.

Fig. 1.

A NMR analysis following decomposition of TnBPSe after hot injection. a The 31P NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture over time, showing that the relative amount of TnBPSe decreases as the amount of TnBPO increases. b The percent composition of TnBPSe (navy blue circles) and TnBPO (royal blue squares) in the TnBPSe decomposition reaction over time. 31P and 77Se NMR of TnBPSe before reaction can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1. Trend lines are provided as guides to the eye

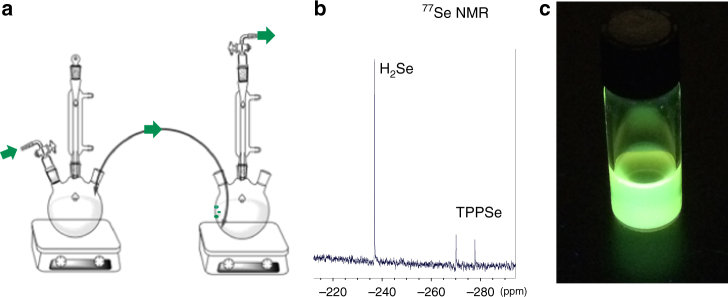

The presence of an insoluble red powder around the edges of reaction vials, similar to the color of selenium oxide, suggested that a gaseous selenium product resulting from the TnBPSe decomposition had been formed, which we hypothesized to be hydrogen selenide (H2Se). Figure 2a shows a diagram of the experimental apparatus used to test for H2Se. The thermal decomposition reaction of TnBPSe takes place in one flask, and any gases formed flow through a cannula to a second flask where they collected. For this experiment, TnBPSe was rapidly injected into hot octanoic acid in tetradecane (250 °C) in the first flask, exactly mimicking the reaction conditions for QD synthesis with the exclusion of cadmium. In the second collection flask, the cannula was submerged in carbon disulfide (CS2) cooled in an ice bath, allowing the gaseous products to dissolve. H2Se is soluble in carbon disulfide, and was collected for analysis by77Se NMR spectroscopy. A positive control experiment was conducted where H2Se was generated in the first flask by the well-known reaction of zinc selenide with hydrochloric acid30, and collected in CS2 in the second flask.

Fig. 2.

Identifying the selenium decomposition product. a The experimental setup used to identify H2Se as the gaseous selenium source. This panel was generated using templates in ChemDraw Professional 16.0. b The 77Se NMR spectrum of H2Se with TPPSe external standard. NMR characterization of TPPSe can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6. c Fluorescent CdSe nanocrystals under UV irradiation synthesized from the H2Se generated in situ, the absorbance spectrum is in Supplementary Fig. 7

Comparison of the 77Se NMR spectra of the control experiment and the TnBPSe decomposition experiment, seen in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5, show that both reactions contain matching peaks, consistent with the expected NMR peak shift for H2Se in CS2 (Supplementary Table 1)30, 31. The observation of Se in the rightmost flask provides conclusive evidence that H2Se is the selenium containing decomposition product of TnBPSe. Furthermore, we confirmed that the H2Se produced from the TnBPSe decomposition can react to form CdSe nanoparticles, by using the cannula apparatus in Fig. 2a with cadmium oleate in tetradecane at 250 °C in the second flask replacing CS2. H2Se from the TnBPSe decomposition reaction in the first flask was bubbled through the cadmium oleate resulting in the synthesis of CdSe nanoparticles shown in Fig. 2c.

To quantify the amount of H2Se produced, a coaxial insert NMR tube was employed to allow the use of an external77Se NMR standard. Triphenylphosphine selenide (TPPSe) was chosen as the external standard because its chemical shift appears near to, but distinct from, that of H2Se. The77Se NMR showing the H2Se singlet and TPPSe standard doublet can be seen in Fig. 2b. From77Se NMR integrated peaks, we calculated an average of 36% conversion of TnBPSe to H2Se after 15 min of reaction. The discrepancy between the conversion yields from 77Se NMR (36%) and31P NMR (30%) is within experimental error (Supplementary Note 1). Interestingly, we also observed that hot injection of the phosphine-chalcogenide (as opposed to heating the phosphine-chalcogenide already in solution) doubles the conversion rate of TnBPSe, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. This finding indicates that the hot injection method, which is known to be important for a narrow particle size distribution21, is directly contributing to the conversion kinetics of phosphine-chalcogenide precursors to H2Se. Finally, we also observe that increasing the amount of excess carboxylic acid in solution increases the conversion of TnBPSe to TnBPO (Supplementary Fig. 9). This result indicates that carboxylic acid actively participates in the P=Se bond cleavage as has been proposed previously14.

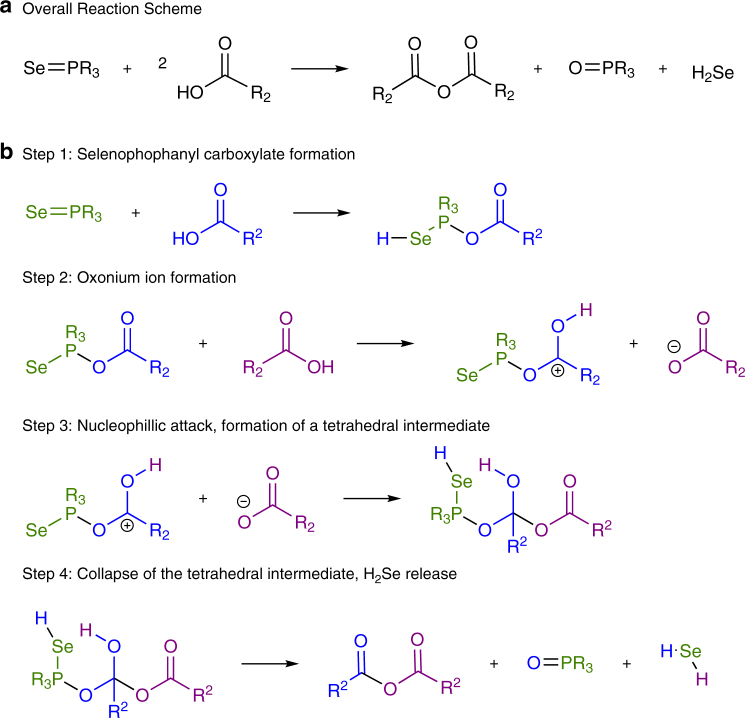

We suggest that tertiary phosphine decomposition is a critical and necessary first step in the formation of CdSe QDs. A proposed overall reaction scheme for this process is shown in Fig. 3a, with details of the progression of the reaction mechanism shown in Fig. 3b and arrow pushing in Supplementary Fig. 10. In this mechanism, carboxylic acid, present in excess in standard QD reactions, attacks the tertiary phosphine selenide, breaking the phosphine selenide double bond, allowing it to be protonated forming an selenophosphanyl carboxylate intermediate. The resulting carboxylate is activated by a second carboxylic acid leading to the formation of an oxonium ion. Subsequently, a tetrahedral intermediate is formed by nucleophilic attack of the second carboxylate on the oxonium ion. The acidic proton of the oxonium ion is in close proximity to the selenium and is able to protonate it a second time, breaking the final P–Se bond and releasing H2Se. The tetrahedral intermediate collapses to yield anhydride and tertiary phosphine oxide, known by-products of QD synthesis14, 27, 28. Chen et al.22 observed the decomposition of phosphine sulfides to phosphine oxides in acidic conditions at temperatures greater than 150 °C, resulting in the release of hydrogen chalcogenide, showing that this mechanism is not unprecedented or implausible. In addition, the reaction was run in tetradecane, a non-coordinating solvent, ruling out a previously reported pathway where elemental Se in octadecene (ODE) reacts with the double bond in ODE to generate H2Se at high temperatures32, 33. The use of octanoic acid eliminates the possibility of this alternative mechanism occurring since, unlike oleic acid, it has no double bonds. The reactivity of octanoic acid and oleic acid was found to be sufficiently similar (Supplementary Fig. 11). Also, experiments were performed to check for the effect of hydrocarbon chain length and purity of reagents on the reactivity of the phosphine selenide. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, TOPSe had similar reaction kinetics to TnBPSe, indicating that within this range there was no effect. The purity of reagents did not significantly affect the rate of TXPSe decomposition, Supplementary Figs. 13–15.

Fig. 3.

Reaction scheme for H2Se release. a The proposed reaction scheme for the decomposition of tertiary phosphine selenide in the absence of Cd. b The steps of the proposed reaction mechanism with the tertiary phosphine in green and carboxylic acids in blue and purple. Newly formed bonds are in black

Interestingly, when different carboxylates are used in the reaction: oleic acid and cadmium acetate, we observe a mixed anhydride species through GCMS (gas chromatography mass spectrometry, Supplementary Fig. 16). Mixed anhydrides that are formed through the reaction of acetic anhydride and oleic acid have a higher reactivity compared to symmetric anhydrides34, and are in a fast equilibrium with symmetric anhydrides and free carboxylic acid (reaching equilibrium in <10 min at 100 °C)35. The presence of mixed anhydride species provides strong evidence that the anhydrides and free carboxylic acids are available to react during normal QD syntheses, perpetuating the mechanism described above.

Thermal decomposition of cadmium octanoate

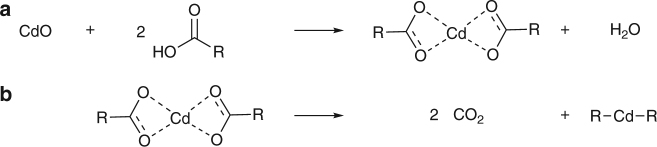

In addition to the phosphine-chalcogenide, at elevated temperatures metal carboxylates can decompose by losing a carboxyl group and liberating carbon dioxide (CO2)36, leading us to consider the decomposition of the metal carboxylate as another possible reaction pathway en route to QD nucleation. Decomposition of cadmium carboxylate would form a highly reactive alkyl cadmium product (Fig. 4b), a historically common cadmium precursor for QD synthesis with tertiary phosphine selenides2. To test our hypothesis, the decomposition of cadmium octanoate under standard QD synthesis conditions was observed as a model for the decomposition of the common QD precursor, cadmium oleate. Alkyl cadmium is air sensitive, pyrophoric, very reactive, and not easily observed directly, so to verify the thermal decomposition of cadmium octanoate (Fig. 4b), we tracked the formation of CO2.

Fig. 4.

Cadmium carboxylate reaction schemes. a The formation of cadmium carboxylate. b The thermal decarboxylation as proposed in this work

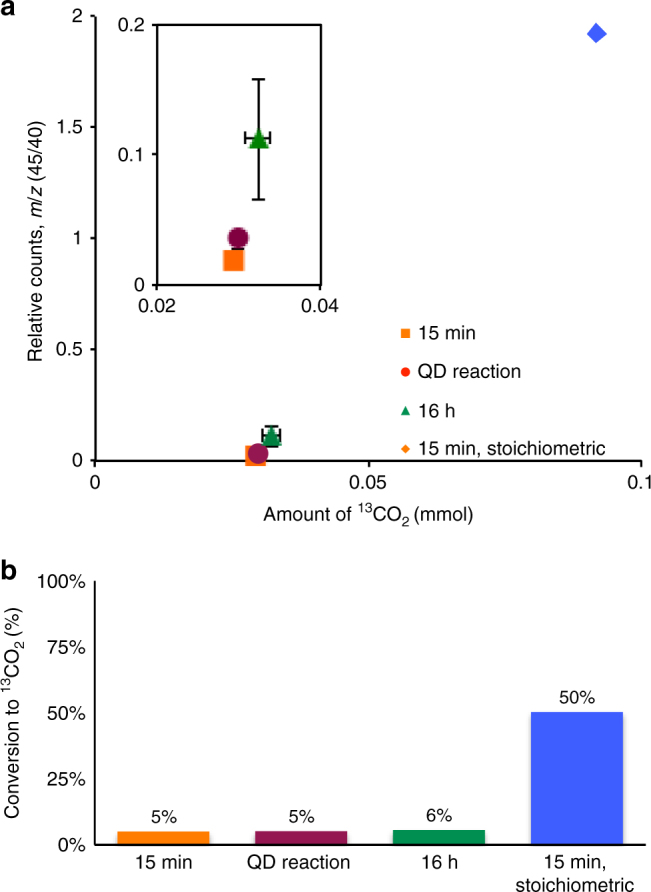

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 17, 13C-labeled cadmium octanoate was used to discern CO2 generated by the decarboxylation reaction from that of the atmosphere. GCMS analysis, shown in Fig. 5, revealed that 13CO2 was present in the headspace of the reaction, indicating that the 13C-labeled cadmium octanoate had undergone decarboxylation, releasing 13CO2 and forming alkyl cadmium (Fig. 4b). A description of the reaction vessel is present in Supplementary Fig. 18. Note that formation of CO2 from metal carboxylates has also been postulated to arise from an alternative route that involves formation of metal carbonates or metal oxides (Supplementary Fig. 19)28. However, we observed no precipitation of cadmium oxide or cadmium carbonate in our reactions, signifying that the observed CO2 was likely accompanied by formation of the metal alkyl.

Fig. 5.

Detecting 13CO2 from cadmium octanoate decomposition. a Headspace samples from different reaction conditions and the amount of 13CO2 detected, the calibration curve to which these values are fit in Supplementary Fig. 20. b Bar graph of calculated percent conversion of cadmium carboxylate to 13CO2 during the decomposition reaction. Samples compared include the headspace from; a Se-free decomposition with 12 times excess carboxylic acid after 15 min, a QD reaction, a Se-free decomposition with stoichiometric amounts of carboxylic acid after 15 min (QD absorbance spectrum in Supplemental Fig. 21, and a Se-free decomposition with excess carboxylic acid after 16 h. Tabular data can be found in Supplemental Table 2. Error bars depict the standard error of the mean of five replicate experiments

GCMS was further used to quantify the amount of 13CO2 that formed during reaction. We compared the amount of 13CO2 in the headspace to a standard calibration curve made with varying amounts of 13CO2, described in Supplementary Fig. 20. Somewhat surprisingly, the amount of 13CO2 measured reached only 5% of that expected from total decarboxylation of all cadmium carboxylate in solution after 15 min. Even after 16 h the amount detected did not change appreciably, shown in Fig. 5b. Interestingly, when there is no excess carboxylic acid in solution, when the cadmium carboxylate is prepared using stoichiometric amounts of carboxylic acid to cadmium, the amount of 13CO2 observed increases markedly to 50% (Fig. 5b).

This marked increase in reactivity suggests that the carboxylate is acting as a passivating agent, preventing the decomposition reaction to form the alkyl cadmium species, causing only small amounts of CO2 to be released into the headspace. Rapid exchange of carboxylates at the metal center and QD surface are known37, and equilibrium effects are a known limitation to thermal decarboxylation, along with thermal instability of the resulting product, or a preference for an alternative decomposition pathway36. Nonetheless, given that typical CdSe QD synthesis conditions are run in a large excess of carboxylate, it is unlikely that metal-carboxylate decomposition with subsequent metal-alkyl formation can account for the majority of the QDs formed.

Discussion

It is interesting to relate our findings with previous studies of CdSe QD reaction mechanism. Here we have demonstrated that under the high reaction temperatures of typical QD syntheses, phosphine selenide and metal carboxylate decomposition produce highly reactive species that subsequently form QDs. The fact that QDs are formed in one flask containing metal carboxylate, with phosphine selenide precursors present in another flask, with just a cannula connecting the two flasks, indicates that phosphine selenide activation by a cadmium complex is not necessary for phosphine-chalcogenide bond cleavage. Although most previously proposed mechanisms have proposed an intermediate where both cadmium and selenium precursors remain intact and form the first initial CdSe bond14, 16, 17, 19, 27, 38, our proposed mechanism first requires thermal decomposition of the Cd and Se molecular precursors before forming the first CdSe bond. Nonetheless, it is important to note that our study does not preclude the possibility that such direct interaction does occur and could also lead to the formation of QDs.

In a typical CdSe QD synthesis excess carboxylic acid causes rapid, non-uniform QD growth while inhibiting nucleation, resulting in fewer QDs of larger size39–41. This suggests an increased reactivity or availability of precursors during the growth phase but inhibition of nucleation. However, theoretical models of nucleation kinetics predict no dependence on carboxylic acid concentration on nuclei formation from monomer16, 42, 43. These models assume monomer formation is first order in precursor concentration, not accounting for precursor reactions before monomer formation42, 43. Precursor conversion is an important step in QD reaction kinetics, as demonstrated by Hendricks and co-workers through their design of sulfur precursors with tuneable conversion kinetics11, 16, dictating QD size and monodispersity. In this work, we found that increased carboxylic acid concentration resulted in increased tertiary phosphine selenide decomposition yielding more of the active precursor H2Se. We also observed that excess carboxylic acid results in a decreased conversion of cadmium carboxylate to CO2, indicating that decarboxylation is inhibited at high carboxylate concentrations. The converse dependencies on the concentration of carboxylic acid in the two precursor conversion reactions reported here suggest that there is a subtle balance between the two processes and each affect the nucleation and growth phases differently.

It is interesting to question how the rate of conversion of phosphine selenide is affected by the presence of Cd oleate in solution. The presence of Cd oleate could certainly change the kinetics of the phosphine decomposition, or act as a Lewis acid, as others have proposed14, 15, 32, forming a Lewis acid-base complex as the first step to CdSe QD formation. To parse out the role of Cd as a Lewis acid we monitored the conversion of phosphine selenide to phosphine oxide in the presence of three equivalents (vs. TnBPSe) of zinc-, cadmium-, or silver-oleate. If the release of selenium was dependent on cadmium acting as a Lewis acid, we may expect silver (also a “soft” metal) to react similarly, but would expect zinc to be the least reactive because it is a harder metal. As seen in Supplementary Fig. 22, zinc follows the reactivity of the metal-free decomposition after 10 min. The lack of reactivity before 10 min is mirrored in ZnSe synthesis with Zn stearate reported by Li et al.44 Silver oleate also had overall similar conversion to the metal-free case. However, with cadmium present we see a rapid increase in phosphine selenide conversion rate in the first minute after hot injection, Supplementary Fig. 23.

We attribute the initial fast consumption of phosphine selenide in the presence of cadmium to the burst nucleation of CdSe, which provides a large driving force for the release of selenium. Such an attribution has precedent, as it has been shown that the Cd and Se precursor reaction rates depend on the rate of QD nucleation14,16,45. According to our results, in the absence of cadmium H2Se gas is evolved. However, in the presence of a cadmium source H2Se rapidly reacts to form CdSe nuclei that precipitate from solution into a colloidal suspension. When this occurs as a burst nucleation event during hot injection, the removal of CdSe QDs as products in this reaction creates a large driving force for the precursor conversion reaction. This interpretation is consistent with the slowed precursor reaction kinetics observed for a heat up method of synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 8), as well as the similar kinetics observed for Cd after the first minute of hot injection (Supplementary Fig. 23).

The formation of the highly reactive species H2Se and a metal alkyl in situ during QD syntheses suggests that modern methods used to synthesize QDs are not actually that different from methods used decades ago. For example, some of the earliest reported syntheses of metal chalcogenide QDs involved injecting H2Se into a solution containing metal salts46, 47. And, in an early seminal breakthrough alkyl cadmium precursors with tertiary phosphine selenide enabled the synthesis of high-quality CdSe QDs with well-controlled size2. Our results indicate that QD syntheses have evolved such that these highly reactive molecular precursors used decades ago are likely still the reactive species, but are simply produced in a more controlled manner today. Rational design of metal and chalcogen precursors that decompose into metal alkyl or hydrogen selenide species in a controlled manner could be a possible route to significant future breakthroughs in QD synthesis.

In summary, we have determined that no less than three separate mechanisms contribute to the formation of metal chalcogenide bonds during the formation of CdSe and related QDs. Analysis of independent thermal decomposition reactions of cadmium carboxylate and tertiary phosphine selenide suggests that each organometallic precursor decomposes independent of one another in standard QD synthesis conditions to form highly reactive species, alkyl cadmium and hydrogen selenide, respectively. A third mechanism does not involve precursor decomposition and would include secondary phosphine-chalcogenide impurities reacting with metal carboxylates5. The decomposition of tertiary phosphine-chalcogenide to form tertiary phosphine oxide and H2Se at a high yield makes this pathway likely the dominant one. The alkyl cadmium decomposition pathway and the secondary phosphine-chalcogenide impurity pathway are likely much less important but can account for upwards of 10% of the synthesized QDs. These findings are important in that they provide a rational roadmap for improving the current approach to designing better QD synthetic methods. By understanding the chemistry that leads to the initial QD nucleation event, new organometallic precursors can be designed to control this decomposition to yield highly engineered QDs of desired sizes, shapes, properties, and chemical compositions.

Methods

Synthesis of selenium precursor

Tri-n-butylphosphine selenide was prepared by mixing selenium pellets with tri-n-butylphosphine (99%) in toluene under a nitrogen atmosphere to make a 1 M solution, heating at 60 °C until homogeneous.

Tertiary phosphine selenide decomposition

Tri-n-butylphosphine selenide (2 mmol) was injected into a flask of octanoic acid (4 mmol) in tetradecane (8 mL) at 250 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere for 15 min. The resulting products in solution were analyzed by 1H, 31P, and 77Se NMR at different time points and carboxylic acid concentrations. A cannula transfer apparatus was assembled as in Fig. 2a so that the gases from the TnBPSe decomposition flask were bubbled through the solution in the second flask. The gaseous products were collected in carbon disulfide (12 mL, CS2) at 0 °C (ice bath) in the second flask. The solution reacted for 15 min, the amount of time necessary to make CdSe QDs in the same apparatus. The solution in CS2 was then prepared in a NMR tube with a STEM coaxial insert and a triphenylphosphine selenide (TPPSe) external standard. A control experiment was conducted in parallel to allow for comparison of spectra; a CS2 solution of hydrogen selenide was generated by reaction of zinc selenide with a dropwise addition hydrochloric acid in the first flask, as reported by Schneider and Wieghardt.30 In addition, the second flask was replaced with Cd oleate in tetradecane and resulted in the formation of CdSe nanocrystals.

Cadmium octanoate decomposition

13C-labeled cadmium octanoate was prepared by heating 1-13C-octanoic acid (4 mmol) and cadmium oxide (2 mmol) in tetradecane by heating to 210 °C for 30 min in a schlenk flask. The resulting clear, colorless liquid was degassed and the flask was sealed. The side arm of the flask was sealed with a septum and purged with nitrogen. The sealed flask was then heated to 280 °C for 15 min, analogous to the conditions of a QD synthesis. The headspace of the reaction was analyzed using GCMS. The purged space in the arm of the flask was analyzed to ascertain a background concentration of gases. The Teflon pin of the flask was then opened allowing the headspace of the reaction to mix with the atmosphere in the arm of the flask. A second sample of gas was taken through the septum and the relative concentrations of gases before and after mixing was determined. A calibration curve was created by varying the amounts of 13CO2 added to a schlenk flask filled with an equivalent volume of tetradecane as in the experimental unknowns with an argon internal standard was added equally across all samples. The ratio of counts vs. the internal standard was calculated by dividing the counts of 13CO2 (m/z = 45) by those of argon (m/z = 40). The average for each concentration was taken over five replicates.

NMR characterization

Proton (1H), carbon (13C), phosphorus (31P), and selenium (77Se) NMR spectra were recorded at ambient temperature on an Avance 500 (500 MHz) spectrometer. Chemical shift (δ) is recorded in ppm and coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz (Hz).

GCMS characterization

Headspace samples were measured on a Shimadzu GCMS–QP2010. The instrument was operated with an injection temperature of 250 °C, a column temperature ramping from 40–240 °C, an ion source temperature of 225 °C, and a column flow rate of 17 psi helium carrier gas at 1.05 mL/min.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding form the NSF (CHE-1609365). Jalil Shojaie and Terry O’Connell (Univ. of Rochester) are thanked for their assistance in conducting the GCMS experiments. We thank Chris Evans and Brett Swartz for preliminary studies in this research direction. We also thank William B. Jones, Robert K. Boeckman Jr., and Nicholas J. Gower (Univ. of Rochester) for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

L.C.F. and T.D.K. conceived of the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. L.C.F. conducted the experiments.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02946-1.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-017-01936-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Steigerwald ML, Brus LE. Semiconductor crystallites: a class of large molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990;23:183–188. doi: 10.1021/ar00174a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CB, Norris DJ, Bawendi MG. Synthesis and characterization of nearly monodisperse CdE (E=S, Se, Te) semiconductor nanocrystallites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:8706–8715. doi: 10.1021/ja00072a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng X, Wickham J, Alivisatos AP. Kinetics of II-VI and III-V colloidal semiconductor nanocrystal growth: ‘Focusing’ of size distributions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5343–5344. doi: 10.1021/ja9805425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng ZA, Peng X. Nearly monodisperse and shape-controlled CdSe nanocrystals via alternative routes: nucleation and growth. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3343–3353. doi: 10.1021/ja0173167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans CM, Evans ME, Krauss TD. Mysteries of TOPSe revealed: insights into quantum dot nucleation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10973–10975. doi: 10.1021/ja103805s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei HHY, et al. Colloidal semiconductor quantum dots with tunable surface composition. Nano Lett. 2012;12:4465–4471. doi: 10.1021/nl3012962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sowers KL, et al. Chemical physics. Chem. Phys. 2016;471:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphys.2015.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik MA, Revaprasadu N, O’Brien P. Air-stable single-source precursors for the synthesis of chalcogenide semiconductor nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2001;13:913–920. doi: 10.1021/cm0011662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cumberland SL, et al. Inorganic clusters as single-source precursors for preparation of CdSe, ZnSe, and CdSe/ZnS nanomaterials. Chem. Mater. 2002;14:1576–1584. doi: 10.1021/cm010709k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair PS, Scholes GD. Thermal decomposition of single source precursors and the shape evolution of CdS and CdSe nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. 2006;16:467–473. doi: 10.1039/B513108A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendricks MP, Campos MP, Cleveland GT, Jen-La Plante I, Owen JS. A tunable library of substituted thiourea precursors to metal sulfide nanocrystals. Science. 2015;348:1226–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Kergommeaux A, et al. Synthesis, internal structure, and formation mechanism of monodisperse tin sulfide nanoplatelets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:9943–9952. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preske A, Liu J, Prezhdo OV, Krauss TD. Large-scale programmable synthesis of PbS quantum dots. ChemPhysChem. 2016;17:681–686. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201500909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Owen JS, Alivisatos AP. Mechanistic study of precursor evolution in colloidal group II−VI semiconductor nanocrystal synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:305–312. doi: 10.1021/ja0656696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen JS, Park J, Trudeau PE, Alivisatos AP. Reaction chemistry and ligand exchange at cadmium−selenide nanocrystal surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12279–12281. doi: 10.1021/ja804414f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen JS, Chan EM, Liu H, Alivisatos AP. Precursor conversion kinetics and the nucleation of cadmium selenide nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:18206–18213. doi: 10.1021/ja106777j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Rodríguez R, Liu H. Mechanistic study of the synthesis of CdSe nanocrystals: release of selenium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1400–1403. doi: 10.1021/ja209246z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rempel JY, Bawendi MG, Jensen KF. Insights into the kinetics of semiconductor nanocrystal nucleation and growth. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4479–4489. doi: 10.1021/ja809156t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.García-Rodríguez R, Liu H. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of the binding of trimethylphosphine selenide to cadmium oleate. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2014;118:7314–7319. doi: 10.1021/jp411681f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Rodríguez R, Liu H. Mechanistic insights into the role of alkylamine in the synthesis of CdSe nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:1968–1975. doi: 10.1021/ja4110182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vreeland EC, et al. Enhanced nanoparticle size control by extending LaMer’s mechanism. Chem. Mater. 2015;27:6059–6066. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b02510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen CH, Brighty KE. A new phosphine-sulfides-to-phosphine-oxides exchange reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:4421–4424. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92189-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helinski J, Skrzypczynski Z, Wasiak J, Michalski J. Efficient oxygenation of thiophosphoryl and selenophosphoryl groups using triflouroacetic anhydride. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4081–4084. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94505-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandblom N, Ziegler T, Chivers T. density functional study of the bonding in tertiary phosphine chalcogenides and related molecules. Can. J. Chem. 1996;74:2363–2371. doi: 10.1139/v96-263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarado SR, Shortt IA, Fan HJ, Vela J. Assessing phosphine–chalcogen bond energetics from calculations. Organometallics. 2015;34:4023–4031. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruberu TPA, et al. Molecular control of the nanoscale: effect of phosphine-chalcogenide reactivity on CdS–CdSe nanocrystal composition and morphology. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5348–5359. doi: 10.1021/nn301182h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steckel JS, Yen BKH, Oertel DC, Bawendi MG. On the mechanism of lead chalcogenide nanocrystal formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13032–13033. doi: 10.1021/ja062626g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García-Rodríguez R, Hendricks MP, Cossairt BM, Liu H, Owen JS. Conversion reactions of cadmium chalcogenide nanocrystal precursors. Chem. Mater. 2013;25:1233–1249. doi: 10.1021/cm3035642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sowers KL, Swartz B, Krauss TD. Chemical mechanisms of semiconductor nanocrystal synthesis. Chem. Mater. 2013;25:1351–1362. doi: 10.1021/cm400005c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider R, Weighardt K, Nuber B. New p-disulfido and p-diselenido complexes of ruthenium(111). Crystal structure of [(LRum(acac))2(p-S2)]P(F& (L=1,4,7-Trimethyl-1,4,7-triazacyclononane;acac=Pentane-2,4-dionate) Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:4935–4939. doi: 10.1021/ic00074a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birchall T, Gillespie RJ, Verkris SL. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of some selenium compounds. Can. J. Chem. 1965;43:1672–1679. doi: 10.1139/v65-221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng Z, Cao L, Tang F, Zou B. A new route to zinc-blende CdSe Nanocrystals: mechanism and synthesis. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:16671–16675. doi: 10.1021/jp052484x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yordanov GG, Yoshimura H, Dushkin CD. Phosphine-free synthesis of metal chalcogenide quantum dots by means of in situ-generated hydrogen chalcogenides. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008;286:813–817. doi: 10.1007/s00396-008-1840-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards WR, Sibille EC. Mixed carboxylic anhydrides in the Friedel-Crafts reaction. J. Org. Chem. 1963;28:674–679. doi: 10.1021/jo01038a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peydecastaing J, Vaca-Garcia C, Borredon E. Consecutive reactions in an oleic acid and acetic anhydride reaction medium. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2009;111:723–729. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200800189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deacon GB, Faulks SJ, Pain GN. The synthesis of organometallics by decarboxylation reactions. Adv.Organomet. Chem. 1986;25:237–276. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3055(08)60576-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fritzinger B, Capek RK, Lambert K, Martins JC, Hens Z. Utilizing self-exchange to address the binding of carboxylic acid ligands to CdSe quantum dots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10195–10201. doi: 10.1021/ja104351q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim T, Jung YK, Lee JK. The formation mechanism of CdSe QDs through the thermolysis of Cd(oleate)2 and TOPSe in the presence of alkylamine. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2014;2:5593. doi: 10.1039/C4TC00254G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bullen C, et al. High activity phosphine-free selenium precursor solution for semiconductor nanocrystal growth. Chem. Mater. 2010;22:4135–4143. doi: 10.1021/cm903813r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Embden J, Mulvaney P. Nucleation and growth of CdSe nanocrystals in a binary ligand system. Langmuir. 2005;21:10226–10233. doi: 10.1021/la051081l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu WW, Peng X. Formation of high-quality CdS and other II-VI semiconductor nanocrystals in noncoordinating solvents: tunable reactivity of monomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:2368–2371. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020703)41:13<2368::AID-ANIE2368>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abe S, Čapek RK, De Geyter B, Hens Z. Tuning the postfocused size of colloidal nanocrystals by the reaction rate: from theory to application. ACS Nano. 2012;6:42–53. doi: 10.1021/nn204008q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abe S, Capek RK, De Geyter B, Hens Z. Reaction chemistry/nanocrystal property relations in the hot injection synthesis, the role of the solute solubility. ACS Nano. 2013;7:943–949. doi: 10.1021/nn3059168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li LS, Pradhan N, Wang Y, Peng X. High Quality ZnSe and ZnS Nanocrystals Formed by Activating Zinc Carboxylate Precursors. Nano Letters. 2004;4:2261–2264. doi: 10.1021/nl048650e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cossairt BM. Shining Light on Indium Phosphide Quantum Dots: Understanding the Interplay among Precursor Conversion, Nucleation, and Growth. Chem. Mater. 2016;28:7181–7189. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b03408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kortan AR, et al. Nucleation and growth of CdSe on ZnS quantum crystallite seeds, and vice versa, in inverse micelle media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:1327–1332. doi: 10.1021/ja00160a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spanhel L, Weller H, Henglein A. Photochemistry of semiconductor colloids. Electron Injection from Illuminated CdS into attached TiO2 and ZnO Particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:6632–6635. doi: 10.1021/ja00256a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.