Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most frequent malignancy and represents the fourth most common cause of cancer-associated mortalities in the world. Despite many advances in the treatment of CRC, the 5-year survival rate of patients with CRC remains unsatisfactory due to tumor recurrence and metastases. Recently, cancer stem cells (CSCs), have been suggested to be responsible for the initiation and relapse of the disease, and have been identified in CRC. Due to their basic biological features, which include self-renewal and pluripotency, CSCs may be novel therapeutic targets for CRC and other cancer types. Conventional therapeutics only act on proliferating and mature cancer cells, while quiescent CSCs survive and often become resistant to chemotherapy. In this review, markers of CRC-CSCs are evaluated and the recently introduced experimental therapies that specifically target these cells by inducing CSC proliferation, differentiation and sensitization to apoptotic signals via molecules including Dickkopf-1, bone morphogenetic protein 4, Kindlin-1, tankyrases, and p21-activated kinase 1, are discussed. In addition, novel strategies aimed at inhibiting some crucial processes engaged in cancer progression regulated by the Wnt, transforming growth factor β and Notch signaling pathways (pyrvinium pamoate, silibinin, PRI-724, P17, and P144 peptides) are also evaluated. Although the metabolic alterations in cancer were first described decades ago, it is only recently that the concept of targeting key regulatory molecules of cell metabolism, such as sirtuin 1 (miR-34a) and AMPK (metformin), has emerged. In conclusion, the discovery of CSCs has resulted in the definition of novel therapeutic targets and the development of novel experimental therapies for CRC. However, further investigations are required in order to apply these novel drugs in human CRC.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, cancer stem cells, chemoresistance reduction, apoptosis induction

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies and a major cause of cancer-related death worldwide. It is the second most common type of cancer in both genders (women: 10.1%; men: 12.4%) and the number of newly diagnosed CRC cases continues to grow. CRC, according to the WHO, is the third most common cancer, with 1,361,000 cases worldwide in 2012 (1).

The primary treatment of CRC is surgical resection. However, approximately 25% of CRC cases are detected in stage IV (with distant metastases) and almost 50% of CRC patients will develop metastasis during their lifetime (2). The treatment outcomes for these patients are unfavorable, since conventional therapies affect proliferating and differentiated cancer cells from the tumor mass and save cancer stem cells (CSCs). This approach seems to explain the initial post-therapy tumor shrinkage, which is often followed by relapses resulting from the activity of CSCs (3).

Chemotherapy of patients with CRC can be performed either as monotherapy (capecitabine, irinotecan) or with a combined protocol (4–6): LVFU2: 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) + calcium folinate racemate (or levofolinic acid in equivalent dose); FOLFOX4: 5-FU + calcium folinate racemate (or levofolinic acid in equivalent dose) + oxaliplatin; FOLFOXIRI: 5-FU + calcium folinate racemate (or levofolinic acid in equivalent dose) + oxaliplatin + irinotecan; FOLFIRI: 5-FU + calcium folinate racemate (or levofolinic acid in equivalent dose) + irinotecan; CAPOX (XELOX): Capecitabine + oxaliplatin.

Presurgical radiotherapy can be included in two different ways. The first involves five fractions of radiotherapy (5 Gy) each a week before surgical intervention. The second therapeutic mode involves a total of 50.0–50.4 Gy divided into 1.8 or 2.0 Gy fractions, combined with chemotherapy using fluorouracil, either with calcium folinate or with capecitabine. In the second protocol, surgery is delayed and is performed at least six weeks after the last course of radiotherapy. Both protocols ensure similar efficacy (7,8).

Additionally, in recent years, new drugs targeting growth factors or their surface receptors have been introduced as additional therapy for the treatment of CRC (Table I).

Table I.

Conventional chemotherapeutics and monoclonal antibodies used for colorectal cancer therapy.

| Chemotherapeutics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | Name | Type | Mechanism of action | (Refs.) | |

| Taieb et al, 2014; | 5-Fluorouracil | Pyrimidine antimetabolite | Inhibition of thymidylate synthase activity leading to decreased DNA | (6,158–161) | |

| Alberts et al, 2012; | (5-FU) | replication and cell proliferation | |||

| Cao et al, 2015; | |||||

| Longley et al, 2003; | |||||

| Yamada et al, 2013 | |||||

| Schmoll et al, 2015 | Capecitabine | Pyrimidine antimetabolite | Inhibition of thymidylate synthase after cellular thymidine phosphorylase | (162) | |

| (5-FU prodrug) | transforms prodrug to fluorouracil | ||||

| Taieb et al, 2014; | Leucovorin | Folic acid antagonist | Increase in fluorouracil efficacy | (6,158,159,161) | |

| Alberts et al, 2012; | |||||

| Cao et al, 2015; | |||||

| Yamada et al, 2013 | |||||

| Cau et al, 2015; | Irinotecan | Topoisomerase I inhibitor | Metabolically activated in the body to 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin | (159,163–165) | |

| Élez et al, 2015; | (SN-38 prodrug) | (SN-38) by carboxylesterase; reversible stabilization of the | |||

| Sclafani et al, 2015; | topoisomerase I complex results in single-strand DNA breaks; inhibition | ||||

| Fujita et al, 2015 | of DNA synthesis; arrest of the cell cycle at the S/G2 phase | ||||

| Taieb et al, 2014; | Oxaliplatin | DNA alkylator | Formation of crosslinks in DNA; arrest of the cell cycle in the G2/M phase; | (6,158,161,166) | |

| Alberts et al, 2012; | (platin derivative) | apoptosis induction via activation of caspases | |||

| Yamada et al, 2013; | |||||

| de Gramont et al, 2012 | |||||

| Longley et al, 2003; | Tegafur-uracil | Combinatory therapy of | Tegafur is metabolically activated in the body to 5-FU by dihydropyrimidine | (160,167) | |

| Bayoglu et al, 2015 | (UFT) | CRC with 5-FU prodrug | dehydrogenase (DPD); uracil, a competitive inhibitor of DPD, inhibits 5-FU | ||

| and uracil | catabolism and prolongs its life time; uracil decreases 5-FU doses, protecting | ||||

| patients from its toxicity | |||||

| Ben Sahra et al, 2010; | Metformine | Biguanide derivative | Activation of caspase 3; induction of apoptosis; restoration of p53 activity | (136–138) | |

| Ben Sahra et al, 2010; | Monoclonal antibodies used in combination with chemotherapeutics | ||||

| Miranda et al, 2016 | |||||

| Cao et al, 2015; | Bevacizumab | Humanized monoclonal | Blocking of the binding of all known VEGF-A isoforms to VEGF receptors; | (159,166,168–170) | |

| de Gramont et al, 2012; | IgG1 antibody | inhibition of tumor angiogenesis | |||

| Feng et al, 2014; | |||||

| Strickler et al, 2012; | |||||

| Roviello et al, 2017 | |||||

| Élez et al, 2015 | Abituzumab | Humanized monoclonal | Binding to integrin αv heterodimer; inhibition of cell binding to extracellular | (163) | |

| IgG2 antibody | matrix; inhibition of cell migration; Induction of apoptosis | ||||

| Sclafani et al, 2015 | Dalotuzumab | Humanized monoclonal | Inhibition of ligand (IGF-1, IGF-2) binding and induction of IGFR-1 | (164) | |

| IgG1 antibody | internalization and degradation; inhibition of signaling pathways responsible | ||||

| for proliferation and resistance to apoptosis | |||||

| Cunningham et al, 2004; | Cetuximab | Chimeric monoclonal | Antagonist of EGFR; prevention the signaling and ligand-induced | (4,6,158,164,171,172) | |

| Taieb et al, 2014; | IgG1 antibody | dimerization of the receptor; increases susceptibility of EGFR-positive | |||

| Alberts et al, 2012; | cells to immune cytotoxic cells; reduction in tumor growth | ||||

| Sclafani et al, 2015; | |||||

| Huang et al, 2014; | |||||

| Terazawa et al, 2017 | |||||

| Tay et al, 2015; | Panitumumab | Human monoclonal | Antagonist of EGFR; prevention of EGFR autophosphorylation and | (173,174) | |

| Bahrami et al, 2017 | IgG2 antibody | signaling; induction of apoptosis; inhibition of interleukin 8 and VEGF | |||

| production; reduction of tumor growth | |||||

| Françoso and | Ramucirumab | Humanized monoclonal | Binding of the extracellular domain of VEGF and VEGFR-2; inhibition of the | (175,176) | |

| Simioni, 2017; | IgG1 antibody | activation and signaling of VEGF/VEGFR-2; inhibition of angiogenesis | |||

| Ursem et al, 2016 | |||||

5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, EGF receptor; IGF-1/2, insulin-like growth factor-1/2; IGFR, IGF-1 receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Although about 50% of patients respond to conventional therapy, most develop drug resistance during the course of treatment, and recurrence of the disease often follows (9,10). Our review presents the current state of knowledge concerning experimental CRC treatment protocols targeting CSCs through the induction of their proliferation, differentiation, and sensitization to apoptotic signals. The combined therapy consisting of two distinct constituents: Conventional drugs and the novel anti-CSC factor; an improvement of the anticancer therapy efficacy and a reduction in undesirable side effects is hoped for.

2. Identification of cancer stem cells in colorectal cancer

Under physiological conditions, the pool of normal cells is maintained in tissues and organs due to the presence of small subpopulation of stem cells with a great capability to self-renew, proliferate, and differentiate. A tumor can be seen as an abnormal type of tissue whose growth and development are depend on a population of stem cells, termed CSCs (11–13). These CSCs may gain their specific properties-such as self-renewal, unlimited proliferation potential, and ability to differentiate into any mature cancer cell type-as a result of neoplastic transformation caused by the accumulation of some genetic and epigenetic aberrations. Additionally, they develop specific protective mechanisms, such as those directed against immune cells, or insensitivity to standard chemotherapeutics. The CSC hypothesis remains controversial, but the occurrence of CSCs has been identified within both hematological and solid tumors, such as breast and CRCs (11–13).

The identification of CRC-CSCs is based on a set of CSC-associated protein markers (Table II). It is not clear if all of these biomarkers influence CRC progression with the same effect. Furthermore, the great range of these proteins may result from the genetic heterogeneity of cancer cells both within the tumors of a particular patient and between patients (11,14,15). Experimental data from the rodent model of CRC suggest that only 1 in 25 cells (16), or 1 in 262 cells (13,16), possesses the characteristic features of CSCs in the total population of CRC cells. This diversity may result from the complexity of experimental settings. The initial verification of new markers for the isolation of CSCs often follows discoveries in the field concerning either normal tissue stem cells or CSCs of different tumors. However, the selection of the most universal and useful CSCs markers has yet to be performed.

Table II.

Markers of colorectal cancer stem cells.

| Author, year | Marker | Function | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ricci-Vitiani et al, 2007; | CD133 | Prominin-1; membrane glycoprotein, present on | (13,177–179) |

| Botchkina, 2013; | the surface of actively proliferating stem cells; | ||

| Haraguchi et al, 2008; | function unknown | ||

| Zhu et al, 2009 | |||

| Manhas et al, 2016; | CD44 | P Glycoprotein 1; membrane hyaluronic acid receptor | (2,23,26,178,180) |

| Vermeulen et al, 2008; | |||

| Du et al, 2008; | |||

| Haraguchi et al, 2008; | |||

| Botchkina et al, 2009 | |||

| Manhas et al, 2016; | CD166 | ALCAM; membrane glycoprotein, adhesion molecule | (2,23,180) |

| Vermeulen et al, 2008; | |||

| Botchkina et al, 2009 | |||

| Huang et al, 2009; | ALDH1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, detoxification enzyme, transforms | (16,181) |

| Zhou et al, 2015 | retinol to retinoic acid, which regulates proliferation of cells | ||

| Vermeulen et al, 2008 | CD29 | β1 integrin, adhesion molecule | (23) |

| Manhas et al, 2016; | CD24 | Heat-stable antigen; membrane glycoprotein, | (2,23) |

| Vermeulen et al, 2008 | adhesion molecule | ||

| Manhas et al, 2016 | ESA | Epithelial specific antigen, EpCAM, CD326; membrane | (2) |

| glycoprotein, adhesion and signaling molecule; |

ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; ESA, epithelial-specific antigen; ALCAM, activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule.

A minor Bmi-1-positive subpopulation of CSCs is characterized by low mitotic activity, and thus is supposed to constitute the pool of cells which are resistant to chemotherapeutics and responsible for tumor relapse through intense proliferation following therapy (17,18). According to the CSC hypothesis, conventional chemotherapeutics reduce the tumor mass, but are not sufficiently efficient to eliminate all cancer cells, on account of the presence of chemoresistant CSCs. Efficient DNA repair mechanisms, telomerase activity, insensitivity to proapoptotic signals, and high levels of expression of ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporters) are postulated as the main causes of chemoresistance (19–21).

CD133 protein

The identification and classification of CSCs is rather controversial, as none of the known markers are universal and reliable for the identification of CSCs in all experimental settings (Table II) (22). The most commonly used marker of CRC-CSCs is prominin-1, also named CD133 (22). CD133+ cells are able to reproduce a CRC tumor in a mouse xenotransplantation model, whereas CD133− cells cannot rebuild cancer bulk (11,13). However, the research groups of Ricci-Vittani and Shmelkov showed independently that CD133− cells also possess high proliferative and differentiating potential, comparable to those of CD133+ CRC-CSCs (13,14). CD133+ CRC-CSCs isolated from human tumors may be cultured in vitro for as long as one year without any change in their phenotype, gaining the ability to form undifferentiated tumor spheres which maintain the ability to engraft (13). Moreover, it has been shown that even a single CD133+ cell is able to reproduce the tumor mass in vivo (23). Human CRCs resistant to a conventional 5-FU treatment have been found to be enriched in CD133+ cells; this is directly correlated with a worse outcome for patients (24). However, knockout of CD133 has been found not to affect the clonogenicity of cancer cells, suggesting that CD133 is a passive marker, rather than a CSC-promoting factor (25–27).

CD44 protein

CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein, a receptor of hyaluronic acid that participates in many cellular processes, including growth, survival, differentiation and motility. CD44+ CD133− cells isolated from human CRC tumors have been shown in vivo to efficiently initiate a xenograft tumor that possesses similar properties to those of the primary tumor. Knockdown of CD44 strongly reduced proliferation of these cells and inhibited tumorigenicity in a mouse xenograft model (26,27).

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH-1) has been identified in both nonmalignant and malignant stem cells. In many neoplasms-such as colon, pancreas, breast, and urinary bladder cancers-this enzyme has been shown to be associated with disease progression (16,28–31). Generally, ALDH-1 is responsible for detoxification and defending against free radicals, although it plays a crucial function in cancer recurrence due to the downregulation of CSCs' metabolism during conventional chemotherapy (16,28–31). The activity of ALDH-1 may be pharmacologically blocked via the specific inhibitor DAEB (diethylaminobenzaldehyde) (30). A combination of DAEB with conventional chemotherapeutics, such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel, increases the level of oxidative stress in cells, enhancing their susceptibility to free radicals and apoptosis. The first promising results of such an approach were demonstrated for breast cancer cell lines (32).

3. The characteristics of CRC-CSCs being considered for CSC-targeting therapeutic strategies

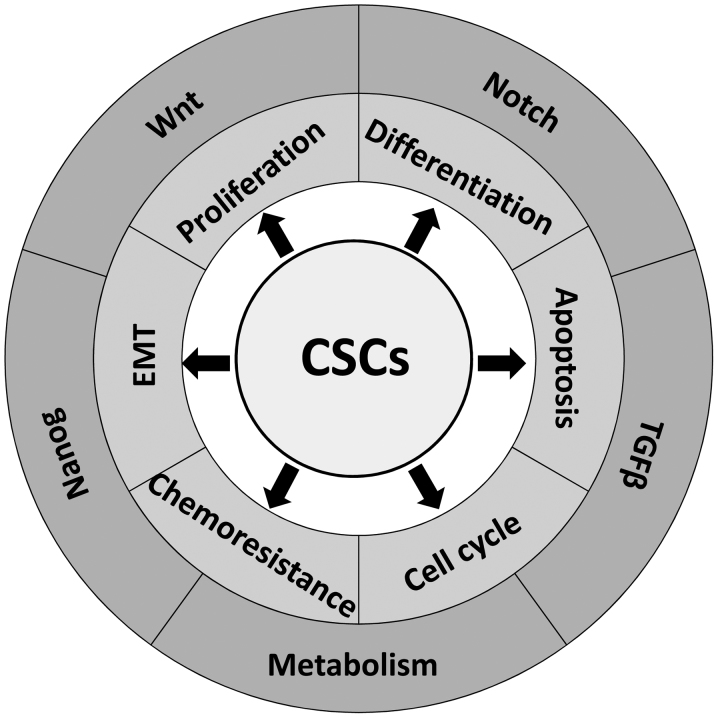

The discovery of CSCs in various tumors has provided new opportunities to overcome chemoresistance and radioresistance of tumor cells through the targeting of this unique population (Fig. 1). To achieve this goal, diverse strategies have been used: the induction of CSC differentiation, the inhibition of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the reduction of angiogenesis, and the suppression of specific signaling or metabolic pathways. Significantly, our increasing understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate CSC quiescence, cell cycle progression, self-renewal, and resistance to proapoptotic signals and chemotherapeutics may provide new therapeutic modalities that will reduce morbidity and increase the overall survival of CRC patients.

Figure 1.

The features characteristic for CRC-CSCs and crucial signaling pathways which are under consideration in regards to CSC-targeting therapeutic strategies. CRC, colorectal cancer; CSC, cancer stem cell.

Induction of CRC-CSC differentiation

The first of the therapeutic approaches is based on the induction of CSC differentiation into more mature types of tumor cells, resulting in a reduction of CSC number. In contrast to CSC, mature cancer cells have no self-renewal ability, cannot proliferate unlimitedly or induce immunological tolerance, and are more susceptible to conventional chemotherapy. Such a therapeutic strategy has been already used in promyelocytic leukemia patients being treated by retinoic acid (RA). Increased intracellular RA concentration upregulates the expression of its normal retinoic acid receptor, RAR, which competitively displaces the cancer-mutated receptor, PML-RAR. RA functions as an agonist of steroid hormone receptors and, due to the binding to transcription factors in the nucleus, may induce the differentiation of abnormal blasts (33).

Impairment of cell cycle checkpoints in CRC-CSCs

Blocking of the cell cycle checkpoint proteins represents a novel approach to treatment aimed at overcoming CSC resistance to conventional cancer therapy. This approach is based on the assumption that cells with dysfunctional checkpoints proliferate in an uncontrolled manner, which could cause genome and metabolic destabilization and lead to cell death.

The combination of two potential therapeutic compounds, flavonoid morin and telomerase inhibitor MST-312, has been demonstrated to lower tumorigenicity of CSCs by targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and telomerase in human CRC cells. A morin/MST-312 combination has been shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of cellular proteins such as p53 and check point kinase 2 (Chk2), which are known to play crucial roles in DNA damage checkpoint control. Inhibition of CRC HT29 and SW620 cells' proliferation in the morin/MST-312 dose-dependent manner and a decrease in CD44+ CRC-CSC count were observed (34).

Martino-Echarri et al studied six CRC cell lines and showed that those expressing a mutated APC gene exhibited a limited response to 5-FU. The sensitivity of APC-mutated CRC cells to 5-FU was significantly increased by deactivating the Chk1 kinase using antisense siRNA-mediated knockdown (35). These data suggest that cancer cells (enriched by CSCs) lacking the activity of cell cycle regulating proteins are much more sensitive to proapoptotic stimulation (35).

Inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Cancer cells derived from epithelial tissue undergo differentiation during which they lose the features of their original tissue and gain some properties of connective tissue cells, during a process called epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is essential for acquisition of the invasion phenotype. EMT is regulated by many intracellular signaling pathways, such as Wnt, Nanog, and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), whose functions are impaired during cancer transformation (36). Moreover, during EMT, non-CSCs may obtain some characteristics of CSCs through transdifferentiation, which enables the transition to the more primitive state and, as it happens, cells have been much better in acquiring therapy resistance (37,38). EMT is one of the possible ways to alter the features of cancer cells, especially of CSCs, which are known to be responsible for the lack of susceptibility to standard chemotherapy (39). The most frequently diagnosed metastases in CRC patients occur in the liver, and the mean 5-year survival rate of such patients is approximately 10% (40).

4. Crucial signaling pathways associated with efficient maintenance of CRC-CSCs: Potential targets for therapy of CRC-CSC

Wnt signaling crucial for CRC-CSC features and survival

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been implicated in the maintenance of the intestinal crypt stem cell pool, and Wnt signaling dysregulation (through either loss of APC function or oncogenic β-catenin mutations) has been identified in 70% CRC tumors (41,42).

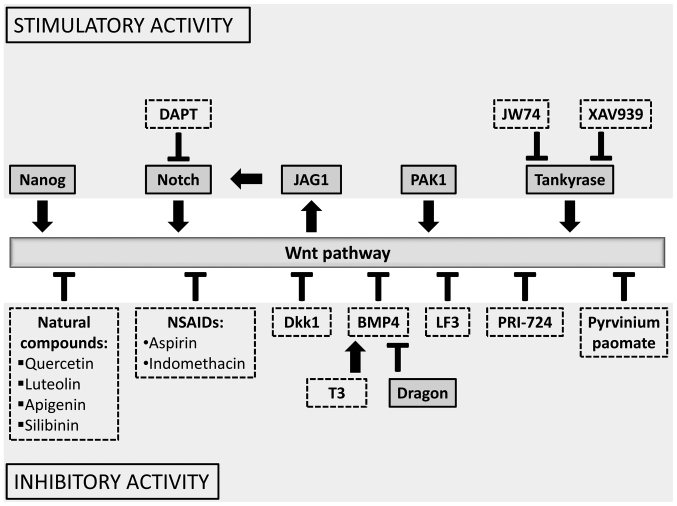

The Wnt pathway is evolutionary conserved and consists of a family of secreted glycoproteins, known as the 19 distinct Wnt ligands in mammals (1,42–44). The importance of this pathway is revealed by its role in the establishment of embryonic axis, cell fate determination, maintenance of adult tissue homeostasis, and regeneration (45,46). Thus, loss of APC allows gastrointestinal stem and progenitor cells to continue proliferating without dying (41,42). Moreover, in a proof-of-principle assay, β-catenin was demonstrated to be required for clonal growth of human CRC cell lines, and targeted deletion of the mutated, constitutively active form of β-catenin abolished the ability of the CRC cell line SW480 to grow in vitro (47). Our paper is aimed at presenting a few therapeutic compounds that target the cytoplasmic β-catenin destruction complex or inhibit expression of the target genes (1,42) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The influence of chosen compounds/proteins on the Wnt signaling pathway which are under consideration as either potential therapeutic targets (continuous line) or potential therapeutic/adjuvant agents (dotted line).

A recent study has suggested that one protein, p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) is an effective stimulator of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and may be a good target for CRC treatment, since PAK1 inhibition has been found to give a synergistic effect with 5-FU (48). It has been shown that PAK1 is associated with the maintenance of stem-cell-like features of CRC-CSCs, such as the expression of CD44, tumorigenicity, and spherogenicity in both in vitro and in xenograft tumor models in vivo (48).

Pyrvinium pamoate, an antiparasitic drug, has been shown to inhibit LRP6-mediated axin degradation and the potency of β-catenin stabilization (49). Pyrvinium treatment of HCT116 and SW480 CRC lines with mutated APC or β-catenin (CTNNB1) genes inhibited both Wnt signaling and cell proliferation. Additionally, some other findings have demonstrated the allosteric activation of CK1α to be an effective mechanism for inhibiting Wnt signaling (49).

The discovery of tankyrases (ADP-ribosylating enzymes) and their role in the direction of axin for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (50–53) has made a significant contribution to this field, as it may provide a new way of targeting the Wnt pathway (53). Inhibition of tankyrases causes the stabilization of axin, which enhances the destruction of β-catenin and reduces Wnt signaling (51). Tankyrase (Tnk) inhibition with the use of new compounds, such as JW74 and XAV939, has also been shown to reduce growth, induce apoptosis and differentiation of cancer cells, and inhibit stem-cell properties and migration of CSC-like cells in cancer lines of diverse origins (osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma, colon) (42). Several small Tnk inhibitors have been reported to possess anticancer efficacy against cell lines of diverse origin, both in vitro and in vivo in xenograft mouse models (50,51,54,55). However, the clinical utility of Tnk inhibitors is at present limited by intestinal toxicity and low therapeutic index in a mouse model (56).

PRI-724, a second generation specific CBP/catenin (cyclic AMP response element binding protein) antagonist has been shown to be safe in preclinical studies. PRI-724 disrupts the complex of β-catenin with CBP, which reduces the expression of a subset of Wnt target genes that are important in the proliferation of CRC cells (57). Several phase I/II trials are ongoing in hematological malignancies, pancreatic cancer, and colon cancer, testing the effectiveness of PRI-724 compound (58). Moreover, PRI-724 induced differentiation of CRC xenografts, accompanied by tumor growth suppression (42,59). Recently, the antineoplastic activity of the LF3 compound, which directly inhibits β-catenin/TCF4 interaction, was reported (59). LF3 treatment of colon, head, and neck cancer cells resulted in the suppression of Wnt activity and reduced self-renewal properties of CSCs (54).

Dickkopf-1 (Dkk1) as a potential target in CRC therapy

Dkk1-a potent, soluble Wnt pathway inhibitor-is reported to be a promising molecule in potential therapy of CRC (60). It has an affinity to one of the coreceptors LRP5/6 affecting the formation of the active receptor complex, Frizzl/LRP5/6, which induces endocytosis of those receptors, inhibiting Wnt signaling.

Additionally, Dkk1 has a role in embryogenesis and its level is regulated by negative feedback with Wnt pathway effectors, such as β-catenin (61). However, in CRC, this mechanism is disturbed by mutations and epigenetic changes in genes encoding β-catenin (62). It has been shown in 217 CRC patients that Dkk1 overexpression is inversely related to tumor grade, presence of metastasis, and the recurrence rate of colon cancer. In samples obtained from patients with high Dkk1 levels, increased expression of E-cadherin and cytoplasmic β-catenin, and a reduced level of vimentin (an EMT marker) were observed in comparison to Dkk1-negative samples (62). Additionally, the overexpression of Dkk1 in CRC HCT-116 cells allowed the maintenance of epithelial phenotype and led to diminished expression of transcription factors characteristic of EMT (such as Snail and Twist), but also decreased the expression of CSC markers (such as CD133 and Lgr-5) (63). An immunocytochemical analysis has shown a correlation direct between Dkk1 expression and decreased microvessel density, as well as VEGF expression in CRC tumors. CRC cells overexpressing Dkk1 formed smaller tumors following xenotransplantation, with a significantly lower number of small blood vessels (64). Hence, the Dkk1 protein can suppress the progression of the colon cancer, possibly through EMT inhibition, and could serve as a potent target of antitumor therapy (64,65).

Natural compounds targeting the Wnt signaling pathway

Flavonoids, polyphenolic compounds, constitute a very large group of natural products and are one of the most characteristic classes of compounds in plant metabolism (42). Their therapeutic anticancer properties have been studied for decades and are related to the ability of these molecules to modulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (66–68). Flavonoids have been shown to affect different elements of this signaling pathway, varying from ligand receptor recognition and binding (Wnt/Frizzled/LRP5/6), to the methylation of genes encoding Wnt components (1).

Quercetin, one of the most studied flavonoids in clinical trials, has been suggested as a potential anticancer drug in CRC (1,67,68) due to its modulation of Wnt activity (1,56,57). Quercetin interacts with β-catenin and inhibits the binding between β-catenin and TCF (69). Moreover, quercetin, as well as the flavonoids luteolin and apigenin, inhibits GSK-3β, which is a multifunctional serine-threonine kinase involved in the formation of β-catenin destructive complex in cytoplasm (67,68).

Silibinin, a flavonolignan from milk thistles, has been shown to exert chemoprevention of intestinal cancer in vitro and in vivo in a mouse model (70,71). The pilot study on CRC patients who were administered silipide, an oral formulation of silibinin and phosphatidylcholine, demonstrated increased levels of silipide in blood, liver, and tumor tissue (70–72). In an experimental follow-up to that study, silibinin has been shown to suppress the growth of CRC SW480 cells in culture and the growth of xenografts through downregulation of β-catenin-dependent signaling (71). The effect of silibinin on CRC-CSCs from the HT29, SW480, and LoVo lines has been shown to be mediated by blocking IL-4/-6 protumorigenic signaling and is associated with decreased mRNA and protein levels of various CSC-associated transcription factors, signaling molecules, and surface markers (such as CD44, NANOG, TERT, SOX-2, SOX-9, and WT1). Furthermore, differentiation assays have indicated the formation of more differentiated clones by silibinin due to the shifting of CSC cell division to asymmetric. These findings support the clinical usefulness of silibinin in CRC intervention and therapy (73).

Recent clinical trials thus suggest that targeting downstream components of the neoplastic Wnt pathway may be a novel therapeutic approach for CRC treatment.

Nanog is crucial in CRC-CSC activity

Nanog is a crucial transcription factor involved in the maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal ability in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells (74). This protein is thought to be responsible for many aspects of cancer development typical of CSCs, such as proliferation, self-renewal, migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Its increased expression has been found to correlate with worse prognosis in many types of cancer, including liver, kidney, colon, prostate, brain, and endometrial cancers (74–82). NANOG activation in cancer cell cultures promotes their transformation into CSCs, as has been shown following ectotopic overexpression of NANOG/NANOG8 in the colon and prostate cancer cell lines (75,80,81).

Meng et al (83) provided evidence that Nanog can be used as a prognostic factor of CRC after they examined 75 human CRC samples, which showed that overexpression of NANOG strongly correlated with poor prognosis and lymph node metastasis (83). Another study conducted immunohistochemical analysis of the expression patterns of CSC-specific markers (such as CD44, CD133, Nanog, and Oct3/4) and of immunosuppressive molecules HLA-G and HLA-E in advanced CRC tumor tissues and noncancerous colon biopsies. Statistically significant increased expression of these genes in CRC tumor tissues has been found in comparison to colon biopsies of healthy subjects. These findings suggest that CRC-CSCs may have increased expression of HLA-G and HLA-E, which may be considered as an immune-evasive mechanism and may thus become new potential targets in the elimination of CRC-CSCs (84).

Lentivirus-mediated Nanog overexpression has been revealed to significantly improve the proliferation and migratory abilities of CRC cells; Nanog was thus supposed to induce EMT through upregulation of the Slug and Snail transcription factors. Moreover, Nanog silencing mediated by interfering RNA in breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in a reduced size of the tumor in a xenotransplantation model and decreased proliferation of these cells (85). Silencing of the NANOG gene was associated with diminishing activation of cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinases (85,86). Downregulation of Nanog in embryonic stem P19 cells resulted in the reduction of pluripotency markers such as Fgf4, Klf2, Mtf2, Oct-4, Rex1, Sox1, Yes, and Zfp143, whereas overexpression of NANOG restored their primary expression levels (86). Interestingly, the expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc were markedly downregulated, and the cell cycle was blocked at the G0/G1 phase following the knockdown of NANOG, while the expression of cyclin E and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) remained unaffected in breast cancer cells (85).

Embryonic NANOG is considered an important regulator of pluripotency, whereas NANOGP8 (NANOG-pseudogene) plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis (75). NANOGP8 can substitute for NANOG in directly promoting stemness in CRC; this conclusion was drawn from the observation that 80% of human CRC liver metastases expressed NANOG and 75% of the metastases contained NANOGP8 transcripts (76). The effects of NANOG inhibition-such as reduced spherogenicity, growth, and expression of embryonic-like transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2)-were partially reversed by the overexpression of NANOGP8 (76,81). Recent studies have suggested that the knockdown of NANOG/NANOG8 genes impairs the ability to migrate and metastasize in xenograft mouse models, as well as the progression of the cell cycle and resistance to apoptosis in CRC cells and embryonic carcinoma cells (75,76,86). Nanog inhibitors administered with cisplatin and other chemotherapeutics had a synergistic effect, and led to apoptosis of esophageal cancer cells (25). The lentivirus vector-mediated inhibition of NANOG/NANOG8 in CRC cells (Clone A, CX-1, LS 174T) decreased the level of Bcl-2 antiapoptotic protein and increased sensitivity to proapoptotic factors ABT-737 and ABT-199 (87). Such combined cell treatment, including inhibitors of Nanog and the modulation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, may provide a new potential therapeutic approach for CRC-CSCs.

Immunocytochemistry and microarray examination showed that NANOG1 expression was limited only to very small population of CSCs, which made up 0.5–2% of all CRC cells (75). Furthermore, NANOG1 expression showed a positive correlation with c-JUN and Wnt/β-catenin/TCF4 expression (75), which are known to be disrupted in CRC oncogenic transformation (41,42). The ectopic expressions of OCT4 and NANOG in lung adenocarcinoma cells led to an increased percentage of CD133+ cells and sphere formation rate, and promoted drug resistance and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (88,89). Since Nanog directly inhibited EMT, it has been suggested that it should be considered as a potential therapeutic approach (89).

TGFβ inhibitors target the epithelial-mesenchymal transition

TGFβ belongs to a superfamily of approximately 30 different pleiotropic proteins that control cell proliferation, migration, adhesion and apoptosis, maintaining tissue homeostasis. Of the three isoforms of TGFβ (TGFβ-1, TGFβ-2 and TGFβ-3), TGFβ-1 has been most widely studied. Signaling is mediated by binding to cell membrane receptors (TGFβR1 and TGFβR2), which results in the phosphorylation of cytoplasmic SMAD proteins being translocated to the nucleus and binding with activators or repressors of genes associated with proliferation, survival, and migration. However, in specific situations, such as the advanced stages of cancer, TGFβ promotes the progression of the disease. During neoplastic transformation, cells lose their susceptibility to TGFβ signaling, which then acts as an autocrine promoter of invasion and metastasis (90,91).

TGFβ is a positive regulator of processes associated with EMT. Among other effects, it stimulates the modification of morphology and the loss of cell polarity, decreases E-cadherin expression, and increases the expression of key transcription factors, such as Snail1/2, Twist, and Zeb1/2 (90). The synthetic proteins P17 and P144, designed to inhibit TGFβ1-mediated pathways, have recently been considered as a useful tool in a clinical approach aimed at reducing liver metastases from CRCs, lymphomas, and thymomas (92,93). Additionally, the administration of peptide P17 blocked the adhesion of cancer cells to cancer fibroblasts and significantly reduced metastasis to the liver, proliferation, and angiogenesis in xenotransplantation model (94). In a CRC CT26 cell line, P17 peptide was involved in the blockage of the T regulatory (Treg) lymphocytes, which synergistically increased the total effect of this compound (92).

The complex analysis of the role of Kindlin-1 in the TGFβ pathway strongly suggests that this regulatory molecule may be a new anticancer target. Kindlin-1 is known to be essential for the maintenance of the structure of cell-matrix adhesion (95). Recently, Kindling-1 has been identified as directly interacting with the key TGFβ/SMAD3 signaling components in numerous CRC cell lines (SW1116, SW480, SW620, Caco2, HCT116, RKO, LST and HT29). Kindlin-1 expression has been found to correlate with the progression of CRC and poor prognosis (96).

BMP regulates differentiation and maturation

Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), belonging to the TGFβ superfamily, has been suggested to be a key regulatory factor in the differentiation of CSCs in CRC (50,97). BMP4, which is secreted by the connective tissue cells of the intestinal wall, has been shown to regulate the maturation and differentiation of normal epithelial cells via paracrine signaling (30,98,99). The distribution of BMP4 increases along the colon crypt axis from bottom to top, and thus its signaling increases toward the top of the crypt. The loss of BMP4 activity in the intestinal epithelium may lead to altered maturation of epithelial cells and, in consequence, to the development of CRC (100). Recently, BMP pathway suppression has been suggested as an essential factor leading to inflammation-induced tumorigenesis of CRC in a mouse model of colonic polypoidogenesis where adenomatous polyps arise several months after induction (97). Additionally, silencing the BMP4 gene by transplacental RNAi administration appeared to be sufficient to induce the formation of colorectal polyps in mice (101).

It has been shown that BMP4 stimulates the maturation and apoptosis of CSCs by reducing β-catenin levels in the nucleus (98,102). Recombinant BMP4 was able to stimulate maturation, differentiation, and apoptosis, leading eventually to higher susceptibility to chemotherapy in human CRC-CSCs. Administration of this protein to nude mice bearing a tumor originating from CRC-CSCs improved the antitumor effect of oxaliplatin and 5-FU. The observed effects did not depend on either SMAD4 expression or microsatellite stability (103).

Additionally, a meta-analysis has demonstrated that the locus rs4444235 of the BMP4 gene may be considered as a risk factor for CRC in some ethnic populations (East Asians and Caucasians) (104). Moreover, Dragon (RGMb, a member of the repulsive guidance molecule family) has been found to be upregulated in CRC. Both mRNA and protein levels were increased in tumor tissue proportionally to CRC progression. The knockdown of the Dragon gene with the use of shRNA (small hairpin RNA) led to a lowered proportion of CD133+ CRC-CSCs in CT26.WT and CMT93 cell lines (105). Dragon, as a co-receptor for BMP signaling (106), has been suggested as a new target for anti-CRC therapy (105).

Recently, triiodothyronine (T3) has been described as playing a role in the regulation of BMP4 signaling by sensitizing CRC-CSCs to chemotherapeutics via significant attenuation of Wnt pathway signaling, and, by extension, via reduction of their tumorigenicity. The influence of T3 on BMP4/Wnt pathway was demonstrated when sphere-forming CSCs from patient samples treated with 5-FU and oxaliplatin presented increased cell death (up to 75%) (107).

Blocking Notch pathway increases the efficiency of anticancer therapy

Under normal circumstances, Notch signaling clearly plays an important role in the maintenance of colon crypt homeostasis. However, the inappropriate activation of the Notch signaling pathway has been reported to be associated with CRC-CSCs. An upregulated Notch pathway has been found to play a role in CSC viability, tumorigenicity, and self-renewal (108,109).

In humans, Notch signaling shows high activity in adenomas and early stage CRCs (65,110), but low activity in advanced, later stage, and metastatic CRCs (111). The molecular mechanisms that cause Notch signaling to be important for early stage CRC initiation are not understood, and only a few mechanistic studies of Notch signaling in human CRC cell lines have been performed (109). Moreover, Hoey et al demonstrated that, by inhibiting DLL4 (Delta-Like 4 Ligand), an important component of the Notch pathway, with human monoclonal antibody in colon carcinoma xenografts, tumor growth and the frequency of CSCs were reduced in comparison to the control (112). Combination treatment with irinotecan and anti-hDLL4 reduced tumor growth and CRC stem cell frequency at higher levels than the anti-DLL4 treatment alone (112,113). This indicates that inhibiting Notch signaling reduces CSC frequencies and sensitizes tumor cells for irinotecan treatment.

However, treatment with anti-DLL4 antibody leads to serious toxic effects in the liver, including sinusoidal dilation and centrilobular hepatocyte atrophy, as observed in mice, monkeys, and rats (114). Using athymic nude mice as a model system, prominent thymic atrophy in immune-competent animals treated with anti-DLL4 antibody was observed. Chronic DLL4 blockade has been shown to activate endothelial cells, disrupt the homeostasis of organs (including the heart, lung, liver, and skin) and induce vascular tumors (114). These reservations notwithstanding, further studies were conducted on both CRC patient-derived specimens (in colon tumor xenografts in NOD/SCID mice) and CRC lines (HCT116 and SW480), and these confirmed the efficacy of such potential therapeutic strategy (115,116).

Van Es and colleagues (117) demonstrated that the blocking of the Notch cascade with a γ-secretase inhibitor dibenzazepine (DBZ) induced goblet cell differentiation in adenomas, even in mice carrying a mutation of the Apc gene, and subsequent tumor growth arrest (117). Additionally, another group induced expression of the Notch intracellular domain in the intestinal epithelium of transgenic mice, impairing both differentiation of the goblet and enteroendocrine cells and resulting in intensive proliferation of immature intestinal progenitor cells (118).

Notch signaling plays an important role in the determination of cell fate. In recent years, this signaling pathway has been shown to play a critical role in regulating the balance between proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of cells in various tissues (108,109). The interaction between Notch receptors and their ligands (Jagged 1 and 2, and Delta-like 1, 3, and 4) results in the proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors by γ-secretase and other proteases, which releases the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) from the plasma membrane and initiates its subsequent translocation into the nucleus. After nuclear translocation, NICD binds to and forms a complex with one of three transcriptional regulators (119–121).

Moreover, the Jagged1 gene (JAG1), which encodes a Notch ligand, has been reported to be transcriptionally activated by the β-catenin/TCF4 complex (122). The expression of JAG1 was limited to enteroendocrine cells of the human small intestine epithelium and was undetectable in the mucosa of human large intestine. In contrast, increased expression was found in half of human colon tumors, although not all tumors with elevated Wnt signaling displayed elevated Jagged1 (122). Experiments on mice have demonstrated that elevated levels of Notch signaling in most intestinal tumors co-occurred with increased JAG1 expression. Targeting of Jagged1 could thus be effective in downregulating Notch signaling in a subset of tumors, as shown in the human HT29Cl16E CRC line (122).

Endothelial cells have been reported to promote the CSC phenotype of human CRC cells through the secretion of the soluble form of Jagged1. In human CRC specimens, CD133− (a basic CRC-CSC markers) and NICD-positive CRC cells have been found to colocalize in perivascular regions (119,123).

Microarray analysis has identified a group of Wnt/β-catenin downstream genes that are directly regulated by Notch (65). These genes were repressed by γ-secretase inhibitors and upregulated by active Notch1, even in the absence of β-catenin signaling, through β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation of the Notch-ligand Jagged1 in Ls174T CRC cells. Consistently, the expression of activated Notch1 partially reversed the effects of blocking Wnt/β-catenin pathway in tumors implanted into nude mice. These results suggest that Notch activation, accomplished by β-catenin-mediated upregulation of Jagged1, is required for tumorigenesis in the intestine (65).

Moreover, a recent study in nude mice indicated that a subpopulation of CRC HCT116 cells chemoresistant to 5-FU and oxaliplatin, enriched in CD133+CD44+ CSCs, was more sensitive to γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT), which depleted the cells in vitro and reduced the growth of tumors derived from these cells (124). Another study reported that upregulation of Notch1 in colonic cancer cells may provide a specific protective mechanism in response to conventional chemotherapeutics (125). These findings suggested that inhibiting the Notch pathway may be an effective strategy for targeting CRC-CSCs and overcoming the resistance of CRC cells to conventional chemotherapeutics.

5. Metabolic target strategy

Although it has been commonly accepted that neoplastic transformation is caused by many genetic and epigenetic factors, little is known of how it affects the metabolism of cancer cells. There are only few reports concerning selected aspects of cancer cell metabolic adaptations which impede cancer progression.

Recent studies have demonstrated overexpression of SIRT1 (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1) in cancer cells resistant to 5-FU and described its implication for the promotion of tumorigenesis and the development of drug resistance (126). SIRT1 is a NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase that can deacetylate histones and a number of nonhistone proteins. SIRT1 has been shown to regulate various cellular processes, including senescence and cell survival under genotoxic and oxidative stress (127,128). A recent meta-analysis showed that, in CRC patients, SIRT1 expression correlates with the development of invasion, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage, thus suggesting that SIRT1 may be regarded as a negative prognostic marker of the overall survival rate of CRC patients (128). SIRT1 has also been shown to be one of the target genes of miR-34a, a small noncoding RNAs that may control gene expression (126,129,130). It has been found that miR-34a inhibits SIRT1 expression directly through binding to the 3′-UTR of its mRNA in HCT116 CRC cells (129). The introduction of miR-34a into 5-FU-resistant DLD-1 cells significantly limited their resistance to 5-FU, which was accompanied by the reduced expression of SIRT1 and E2F family proteins (126,129). These findings suggest that targeting the SIRT1 gene could decrease resistance to 5-FU in human CRC by increasing p53 apoptosis-promoting activity (129).

SIRT1 has been suggested as a key protein in maintaining stem-like features of CRC-CSCs, since SIRT1 was coexpressed with the CD133 marker, and overexpressed in colorectal CSC-like cells (131). Moreover, SIRT1 deficiency decreased percentage of CD133+ cells and their tumorigenicity and the abilities to form colonies and spheres (131). Additionally, the knockdown of SIRT1 gene in CRC SW620 cells reduced expression of several stemness-associated genes (such as Oct4, Nanog, and Tert) (131). These findings suggest that SIRT1 can be considered as a novel prognostic marker or a new target for anti-CRC therapy.

Other studies have focused on a different aspect of cancer cell biology-the Warburg effect, the strong tendency of cancer cells to switch their metabolism into anaerobic respiration (glycolysis), to secrete lactate, and take up high levels of glucose, even in the presence of oxygen in their niche; it particularly affects CSCs (132). This unusual phenomenon has been found to be associated with carcinogenesis due to the inactivation in cancer cells of some metabolic checkpoints, such as dysregulation of AMPK (energy rheostat AMP-activated protein kinase) (10,133,134). The Warburg effect is postulated to create an environment favorable to CSC survival and the reprogramming of non-CSCs into CSCs (135). These observations imply that the elimination of CSCs alone may not be an effective therapeutic approach, because they can be regenerated from non-CSCs. Thus, an optimally effective cancer therapy should rely on the administration of drugs targeting different types of cells within the tumor mass.

Metformin improves anticancer therapy effectiveness

Recently, some inhibitors of AMPK have been considered as potential anticancer therapeutic agents (136–138). Metformin (MET) is the best-established compound in this group of anticancer molecules. MET is an extensively prescribed and well-tolerated first-line therapeutic drug for type-2 diabetes mellitus, which has demonstrated more effective anticancer effects in cancers characterized by hyperinsulinemia, such as breast and colon cancers (139,140). This evidence supports the qualification of MET to preclinical and clinical trials of cancer therapy (136–138).

Metformin has been described as agent capable of directly and indirectly influencing cancer cells through the reduction of glucose and insulin levels in the cancer niche, which decreases cancer progression (139,141). The very first observations of the effects of MET on cancer development were demonstrated in diabetes complicated with CRC; in such patients, CSCs showed lower proliferation and higher rates of apoptosis than patients not pretreated with MET (141). In the same study, it was reported that MET enhanced the antiproliferative effects of 5-FU on CD133+ CSCs in SW620, SW480, and HCT116 CRC cell lines (141–143). Recent analyses of the role of MET treatment in the occurrence of CRC among type-2 diabetes mellitus patients have shown that MET may reduce CRC incidence (144–146).

Moreover, MET has recently been identified as a potential and attractive anticancer adjuvant drug, combined with conventional chemotherapeutics to improve treatment efficacy and decrease chemotherapeutic doses. The molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of MET include insulin-dependent and AMPK-dependent effects, selective targeting of CSCs, reversion of multidrug resistance and inhibition of tumor metastasis (147–149). Positive effects of such synergistic combinatory therapy have been described for a broad spectrum of cancers, including CRC, gastric, hepatic, pancreatic, breast, lung, and prostate cancers (139,148).

The combination of MET and 2-deoxyglucose induces p53-dependent apoptosis via the AMPK pathway and expression of a functional p53 in p53-deficient prostate cancer cells. In addition, such combined therapy arrests prostate cancer cells in the G2/M phase and switched the cell death pattern from autophagic to apoptotic, independently of p53 (136). In CRC SW480 cells, MET inhibited cell growth mainly by blocking the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase, downregulating the expression of cyclin D1, and decreasing telomerase activity (143).

Another study demonstrated that MET effectively sensitizes human DLD-1, HT29, Colo205, and HCT116 cell lines to the proapoptotic activity of tumor-necrosis-factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (134). At the same time, MET has been shown to upregulate Bax and downregulate antiapoptotic myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) levels in CRC cells, responsible for increased TRAIL-mediated cell death in those human CRC cell lines (134).

MET has been shown to inhibit cancer transformation and selectively kill CSCs in four genetically different types of breast cancer (MCF-7, MCF10A ER-Src, SKBR3, and MDA-MB-486). The administration of MET and doxorubicin collectively reduced the number of both CD44highCD24low CSCs and non-CSCs during in vitro culture. Furthermore, this combinatorial therapy reduced tumor mass and prevented relapse significantly more effectively than doxorubicin alone in a xenograft mouse model (150).

Moreover, MET-treated breast cancer cell lines showed downregulation of the CD44+CD24−/low cell proportion via repression of EMT, including through decreasing the level of ZEB, Twist, and Snail2 transcription factors (151). Surprisingly, this combination was effective with a fourfold lower dose of doxorubicin than used in treatment with the chemotherapeutic alone, which enables the reduction of toxicity and an increase in the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach.

However, the therapeutic anticancer activity of MET seems to be controversial, as some groups have not shown its antiproliferative and proapoptotic effect in CRC lines (141,143). Sui et al suggested that MET cannot induce these therapeutic effects as a single agent (152). A possible explanation of these diverse results may be the dependency of MET effectiveness on the experimental settings and cell lines used, as Sui et al (152) used HT29, HCT116, and RKO cells, while the other authors used SW620, and SW480 CRC cell lines (141,143).

6. Chemoprevention: Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs in CRC therapy

After the discovery of increased prostaglandin levels within cancer tissue, including CRC (153,154), the regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was hoped to provide new therapeutic anticancer effects that would slow the progression of the disease. The issue of NSAID use in cancer prevention has been supported by growing evidence from a number of observational studies and post-trial follow-up data (153). Of all cancers, aspirin and indomethacin have been shown to be most effective at reducing the risk of CRC, and even at lower doses demonstrate a 30–40% effectiveness in preventing CRC (153). A case-control study conducted between 1976 and 2011 and including 8634 CRC patients (and 8553 control patients) from the United States, Canada, Australia, and Germany has demonstrated that regular use of aspirin or NSAIDs reduces the risk of CRC (153,155). In a genome-wide investigation of interactions between genes and environment, the use of aspirin or NSAIDs was associated with a lower risk of CRC, and this association differed depending on genetic variation at two SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms) on chromosomes 12 and 15 (154).

The common mechanism through which NSAIDs and their derivatives act is the inhibition of β-catenin/TCF transcriptional activity and, consequently, downregulation of target genes such as cyclin D1. Indomethacin is a cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) and COX-2 inhibitor and exhibits anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. In addition to the more general inhibition of the β-catenin/TCF pathway mentioned above, indomethacin impairs β-catenin gene expression, as shown by the significant reduction of the corresponding mRNA in CRC cell lines (SW480, SW948, LoVo, and HCT-116) (43,153,156,157). Furthermore, indomethacin stimulates β-catenin degradation in a manner independent of APC/GSK3β and proteasome (the Wnt ‘noncanonical’ pathway), even in cells bearing a mutated APC or β-catenin gene CTNNB1.

Aspirin downregulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in CRC cells, leading to reduced transcription of the target genes. Unlike other NSAIDs, this effect seems to be mediated by stabilization of β-catenin in its transcriptionally inactive form (i.e., its phosphorylated form), hampering its activity as a transcription factor (155). All NSAIDs, in addition to their effects on β-catenin and related pathways, act as ligands of PPARγ (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors) by stimulating PPARγ-dependent effects, such as cell cycle block, differentiation, and apoptosis. PPARγ costimulates the expression of cell cycle inhibitors, such as p18, p21 and p27 (155).

Although aspirin and NSAIDs have an undisputable preventive role in CRC development, their wider use in cancer prevention needs to be carefully considered, on account of the increased risk of bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract (153,154,156).

7. Conclusions

In this review, we have summarized the state-of-art in experimental CRC treatment targeting CSCs to prevent or reverse their chemoresistance and reduce their metastatic potential. It is hypothesized that creating combined therapy regimens, in which conventional drugs are supplemented with novel CSC-targeting drugs, might offer improved overall and cancer-free survival rates. A potential dose reduction of conventional chemotherapeutics would help limit their toxicity and improve patients' quality of life.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Polish National Science Center (grant no. NN402684040).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- AKT

protein kinase B

- ALDH-1

aldehyde dehydrogenase 1

- AMPK

energy rheostat AMP-activated protein kinase

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- BMP4

bone morphogenetic protein 4

- CBP

cyclic AMP response element binding protein

- CK1

casein kinase 1

- Chk2

check point kinase 2

- COX-1/2

cyclooxygenase 1/2

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- Dkk1

Dickkopf-1

- DLL4

delta-Like 4 ligand

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- IGF-1/2

insulin-like growth factor 1/2

- IGFR

insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor

- Mcl-1

myeloid cell leukemia 1

- MET

metformin

- NICD

notch intracellular domain

- NSAIDs

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PAK1

p21-activated kinase 1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- RTKs

receptors tyrosine kinases

- RYK

receptor-like tyrosine kinase

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SIRT1

silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1

- SMAD3

SMAD family member 3

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TCF/LEF

T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor

- TERT

telomerase reverse transcriptase

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor β

- Tnk

tankyrase

- TRAIL

tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Amado NG, Predes D, Moreno MM, Carvalho IO, Mendes FA, Abreu JG. Flavonoids and Wnt/β-catenin signaling: Potential role in colorectal cancer therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:12094–12106. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manhas J, Bhattacharya A, Agrawal SK, Gupta B, Das P, Deo SV, Pal S, Sen S. Characterization of cancer stem cells from different grades of human colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:14069–14081. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Franco S, Todaro M, Dieli F, Stassi G. Colorectal cancer defeating? Mol Aspects Med. 2014;39:61–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, Bets D, Mueser M, Harstrick A, Verslype C, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D, ESMO Guidelines Working Group Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii1–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taieb J, Tabernero J, Mini E, Subtil F, Folprecht G, Van Laethem JL, Thaler J, Bridgewater J, Petersen LN, Blons H, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab in patients with resected stage III colon cancer (PETACC-8): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:862–873. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binefa G, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Teule A, Medina-Hayas M. Colorectal cancer: From prevention to personalized medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6786–6808. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, Becker H, Raab HR, Villanueva MT, Witzigmann H, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: Results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926–1933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan K, Wale A, Brown G, Chau I. Colorectal cancer with liver metastases: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection first or palliation alone? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12391–12406. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paldino E, Tesori V, Casalbore P, Gasbarrini A, Puglisi MA. Tumor initiating cells and chemoresistance: Which is the best strategy to target colon cancer stem cells? Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:859871. doi: 10.1155/2014/859871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puglisi MA, Barba M, Corbi M, Errico MF, Giorda E, Saulnier N, Boninsegna A, Piscaglia AC, Carsetti R, Cittadini A, et al. Identification of Endothelin-1 and NR4A2 as CD133-regulated genes in colon cancer cells. J Pathol. 2011;225:305–314. doi: 10.1002/path.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Peschle C, De Maria R. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells. Nature. 2007;445:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature05384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shmelkov SV, Butler JM, Hooper AT, Hormigo A, Kushner J, Milde T, St Clair R, Baljevic M, White I, Jin DK, et al. CD133 expression is not restricted to stem cells, and both CD133+ and CD133- metastatic colon cancer cells initiate tumors. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2111–2120. doi: 10.1172/JCI34401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todaro M, Perez Alea M, Scopelliti A, Medema JP, Stassi G. IL-4-mediated drug resistance in colon cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:309–313. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.3.5389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, Ginestier C, Dontu G, Appelman H, Fields JZ, Wicha MS, Boman BM. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3382–3389. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SP, Lee YT, Yang SH, Miller SA, Chiou SH, Hung MC, Hung SC. Colon cancer stem cells resist antiangiogenesis therapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2013;328:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Huang J. Intestinal stem cells-types and markers. Cell Biol Int. 2013;37:406–414. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dallas NA, Xia L, Fan F, Gray MJ, Gaur P, van Buren G, II, Samuel S, Kim MP, Lim SJ, Ellis LM. Chemoresistant colorectal cancer cells, the cancer stem cell phenotype, and increased sensitivity to insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1951–1957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang EH, Wicha MS. Colon cancer stem cells: Implications for prevention and therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu ZQ, Zhang C, Wang H, Lao XY, Chai R, Gao XH, Cao GW, Fu CG. Downregulation of ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 4 increases sensitivity to neoadjuvant radiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:600–608. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827c2b80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozovska Z, Gabrisova V, Kucerova L. Colon cancer: Cancer stem cells markers, drug resistance and treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68:911–916. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermeulen L, Todaro M, de Sousa Mello F, Sprick MR, Kemper K, Perez Alea M, Richel DJ, Stassi G, Medema JP. Single-cell cloning of colon cancer stem cells reveals a multi-lineage differentiation capacity; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2008; pp. 13427–13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong CW, Kim LG, Kong HH, Low LY, Iacopetta B, Soong R, Salto-Tellez M. CD133 expression predicts for non-response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:450–457. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du Y, Shi L, Wang T, Liu Z, Wang Z. Nanog siRNA plus cisplatin may enhance the sensitivity of chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1759–1767. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du L, Wang H, He L, Zhang J, Ni B, Wang X, Jin H, Cahuzac N, Mehrpour M, Lu Y, Chen Q. CD44 is of functional importance for colorectal cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6751–6760. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berretta M, Alessandrini L, De Divitiis C, Nasti G, Lleshi A, Di Francia R, Facchini G, Cavaliere C, Buonerba C, Canzonieri V. Serum and tissue markers in colorectal cancer: State of art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;111:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honoki K, Fujii H, Kubo A, Kido A, Mori T, Tanaka Y, Tsujiuchi T. Possible involvement of stem-like populations with elevated ALDH1 in sarcomas for chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:501–505. doi: 10.3892/or_00000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim MP, Fleming JB, Wang H, Abbruzzese JL, Choi W, Kopetz S, McConkey DJ, Evans DB, Gallick GE. ALDH activity selectively defines an enhanced tumor-initiating cell population relative to CD133 expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koppaka V, Thompson DC, Chen Y, Ellermann M, Nicolaou KC, Juvonen RO, Petersen D, Deitrich RA, Hurley TD, Vasiliou V. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitors: A comprehensive review of the pharmacology, mechanism of action, substrate specificity, and clinical application. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:520–539. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su Y, Qiu Q, Zhang X, Jiang Z, Leng Q, Liu Z, Stass SA, Jiang F. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 A1-positive cell population is enriched in tumor-initiating cells and associated with progression of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:327–337. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croker AK, Allan AL. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44+ human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:75–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1692-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowak D, Stewart D, Koeffler HP. Differentiation therapy of leukemia: 3 decades of development. Blood. 2009;113:3655–3665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung SS, Oliva B, Dwabe S, Vadgama JV. Combination treatment with flavonoid morin and telomerase inhibitor MST-312 reduces cancer stem cell traits by targeting STAT3 and telomerase. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:487–498. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martino-Echarri E, Henderson BR, Brocardo MG. Targeting the DNA replication checkpoint by pharmacologic inhibition of Chk1 kinase: A strategy to sensitize APC mutant colon cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 2014;5:9889–9900. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pulito C, Donzelli S, Muti P, Puzzo L, Strano S, Blandino G. microRNAs and cancer metabolism reprogramming: The paradigm of metformin. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2:58. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.06.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: An emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:4741–4751. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zubeldia IG, Bleau AM, Redrado M, Serrano D, Agliano A, Gil-Puig C, Vidal-Vanaclocha F, Lecanda J, Calvo A. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell phenotypes leading to liver metastasis are abrogated by the novel TGFβ1-targeting peptides P17 and P144. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Sousa E, Melo F, Vermeulen L. Wnt signaling in cancer stem cell biology. Cancers (Basel) 2016;8:pii: E60. doi: 10.3390/cancers8070060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anastas JN, Moon RT. WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:11–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wierzbicki PM, Rybarczyk A. The Hippo pathway in colorectal cancer. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2015;53:105–119. doi: 10.5603/FHC.a2015.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, Klein OD, de Sauvage FJ. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan KS, Chia LA, Li X, Ootani A, Su J, Lee JY, Su N, Luo Y, Heilshorn SC, Amieva MR, et al. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2012; pp. 466–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim JS, Crooks H, Foxworth A, Waldman T. Proof-of-principle: Oncogenic beta-catenin is a valid molecular target for the development of pharmacological inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1355–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huynh N, Shulkes A, Baldwin G, He H. Up-regulation of stem cell markers by P21-activated kinase 1 contributes to 5-fluorouracil resistance of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:813–823. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1195045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thorne CA, Hanson AJ, Schneider J, Tahinci E, Orton D, Cselenyi CS, Jernigan KK, Meyers KC, Hang BI, Waterson AG, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of Wnt signaling through activation of casein kinase 1α. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:829–836. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang SM, Mishina YM, Liu S, Cheung A, Stegmeier F, Michaud GA, Charlat O, Wiellette E, Zhang Y, Wiessner S, et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature. 2009;461:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nature08356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riffell JL, Lord CJ, Ashworth A. Tankyrase-targeted therapeutics: Expanding opportunities in the PARP family. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:923–936. doi: 10.1038/nrd3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polakis P. Drugging Wnt signalling in cancer. EMBO J. 2012;31:2737–2746. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waaler J, Machon O, Tumova L, Dinh H, Korinek V, Wilson SR, Paulsen JE, Pedersen NM, Eide TJ, Machonova O, et al. A novel tankyrase inhibitor decreases canonical Wnt signaling in colon carcinoma cells and reduces tumor growth in conditional APC mutant mice. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2822–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lau T, Chan E, Callow M, Waaler J, Boggs J, Blake RA, Magnuson S, Sambrone A, Schutten M, Firestein R, et al. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation-driven colorectal tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3132–3144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhong Y, Katavolos P, Nguyen T, Lau T, Boggs J, Sambrone A, Kan D, Merchant M, Harstad E, Diaz D, et al. Tankyrase inhibition causes reversible intestinal toxicity in mice with a therapeutic index <1. Toxicol Pathol. 2016;44:267–278. doi: 10.1177/0192623315621192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lenz HJ, Kahn M. Safely targeting cancer stem cells via selective catenin coactivator antagonism. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1087–1092. doi: 10.1111/cas.12471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duchartre Y, Kim YM, Kahn M. The Wnt signaling pathway in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;99:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang L, Zhu Q, Neuenschwander M, Specker E, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Weis WI, von Kries JP, Birchmeier W. A small-molecule antagonist of the β-catenin/TCF4 interaction blocks the self-renewal of cancer stem cells and suppresses tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:891–901. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aguilera Ó, González-Sancho JM, Zazo S, Rincón R, Fernández AF, Tapia O, Canals F, Morte B, Calvanese V, Orgaz JL, et al. Nuclear DICKKOPF-1 as a biomarker of chemoresistance and poor clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5903–5917. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González-Sancho JM, Aguilera O, García JM, Pendás-Franco N, Peña C, Cal S, García de Herreros A, Bonilla F, Muñoz A. The Wnt antagonist DICKKOPF-1 gene is a downstream target of beta-catenin/TCF and is downregulated in human colon cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:1098–1103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qi L, Sun B, Liu Z, Li H, Gao J, Leng X. Dickkopf-1 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colon cancer cells and contributes to colon cancer suppression. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:828–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z, Sun B, Qi L, Li Y, Zhao X, Zhang D, Zhang Y. Dickkopf-1 expression is down-regulated during the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence and correlates with reduced microvessel density and VEGF expression. Histopathology. 2015;67:158–166. doi: 10.1111/his.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodilla V, Villanueva A, Obrador-Hevia A, Robert-Moreno A, Fernández-Majada V, Grilli A, López-Bigas N, Bellora N, Albà MM, Torres F, et al. Jagged1 is the pathological link between Wnt and Notch pathways in colorectal cancer; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2009; pp. 6315–6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atashpour S, Fouladdel S, Movahhed TK, Barzegar E, Ghahremani MH, Ostad SN, Azizi E. Quercetin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CD133(+) cancer stem cells of human colorectal HT29 cancer cell line and enhances anticancer effects of doxorubicin. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:635–643. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Temraz S, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A. Potential targets for colorectal cancer prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17279–17303. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson JL, Rupasinghe SG, Stefani F, Schuler MA, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Citrus flavonoids luteolin, apigenin, and quercetin inhibit glycogen synthase kinase-3β enzymatic activity by lowering the interaction energy within the binding cavity. J Med Food. 2011;14:325–333. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ning Y, Zhang W, Hanna DL, Yang D, Okazaki S, Berger MD, Miyamoto Y, Suenaga M, Schirripa M, El-Khoueiry A, Lenz HJ. Clinical relevance of EMT and stem-like gene expression in circulating tumor cells of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016 Aug 9; doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.62. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajamanickam S, Velmurugan B, Kaur M, Singh RP, Agarwal R. Chemoprevention of intestinal tumorigenesis in APCmin/+ mice by silibinin. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2368–2378. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]