Abstract

In this study, we examine chronic materialism as a possible motive for Facebook usage. We test an explanatory mediation model predicting that materialists use Facebook more frequently, because they compare themselves to others, they objectify and instrumentalize others, and they accumulate friends. For this, we conducted two online surveys (N1 = 242, N2 = 289) assessing demographic variables, Facebook use, social comparison, materialism, objectification and instrumentalization. Results confirm the predicted mediation model. Our findings suggest that Facebook can be used as a means to an end in a way of self-regulatory processes, like satisfying of materialistic goals. The findings are the first evidence for our Social Online Self-regulation Theory (SOS-T), which contains numerous predictions that can be tested in the future.

Keywords: Psychology, Information science

1. Introduction

1.1. The phenomenon of Facebook

In the last two decades social networking sites (SNSs) like Facebook or Twitter have shown a remarkable increase in popularity and users. Facebook provides a platform to millions of users for various social interactions, such as sharing photographs, interacting through Facebook groups or chatting with friends.

Due to the various possibilities of social interaction and the high number of active users, Facebook offers a new opportunity to examine social behavior (Wilson et al., 2012). There are many studies that have investigated the different factors and causes as to why so many people use Facebook.

In order to identify more basic motives for using Facebook, social psychologists have identified the need for self-presentation as one of the main motives of Facebook users for presenting themselves as positively as possible and to impress other people (Krämer and Winter, 2008). Some personality traits may moderate effects − for example narcissists seem to use Facebook for self-glorification via presenting their ideal-self within their profiles (Mehdizadeh, 2010). In addition, people use Facebook to stay in touch with their friends or groups (Back et al., 2010; Buss, 2012; Nadkarni and Hofmann, 2012). Thus, another motive for using Facebook could be social interaction and the need to belong. Furthermore, some studies have shown that people with low self-esteem use Facebook as a vehicle for social interaction and to increase their self-esteem (Mehdizadeh, 2010; Steinfield et al., 2008). In contrast, other studies questioned whether online friendships really are capable of increasing self-esteem effectively because it was found that people with low self-esteem are able to increase their so-called bridging social capital (i.e., superficial friendships) by using Facebook more frequently, but a clear relationship to self-esteem could not be found (Ellison et al., 2007; Valkenburg et al., 2006).

However, with respect to social interactions, using Facebook does not have uniformly positive effects. For example, in romantic relationships, high Facebook activity can lead to envy because sharing photos with opposite-sex users could be interpreted ambivalently by one’s partner resulting in controlling and tracing the partner’s activities. In fact, a positive relationship between using Facebook and envy in partnerships has been reported in literature (Muise et al., 2009). Altogether, research shows positive outcomes and motives for using Facebook such as the possibility of positive self-presentation and social interaction, but also negative outcomes like envy in partnerships.

Additionally, social comparison could be a motive for using Facebook, since it offers a perfect platform for comparing oneself with others. Users have easy access to all kinds of personal information about others via their profiles, and can also look at relationship status, number of friends or profile pictures, to name a few. Consistently, Lee (2014) found a positive correlation between social comparison orientation, measured with the INCOM scale (Gibbons and Buunk, 2005) and Facebook use intensity, measured with five items developed by Ellison and colleagues (2007). Additionally, McAndrew and Jeong (2012) suggested that social comparison can mediate the link between age and Facebook use: As people get older they tend to use Facebook to a lesser extent because there is a decrease in social comparison orientation. This is likely to the fact that the need for comparison with significant others decreases with age because personal goals, i.e., partnership, work and family are more likely to have been met in old age compared to younger people (McAndrew and Jeong, 2012). Recently, this idea was empirically confirmed by a mediation model (Ozimek and Bierhoff, 2016).

Thus far, we have identified three different motives for using Facebook: The need for self-presentation, the need to belong and the need for social comparison. Perhaps, people also want to attain materialistic goals via Facebook, which could reveal an additional motive for using it: Materialism and the motive to reach materialistic goals.

1.2. Materialism in the modern world

Materialism can be defined as “individual differences in people’s long-term endorsement of values, goals, and associated beliefs that center on the importance of acquiring money and possessions that convey status” (Dittmar et al., 2014). Thus, materialists are described as people who (1) try competitively to have more than others, (2) believe that happiness lies in possessions, (3) have an excessive desire to multiply their possessions in the form of objects, human beings or social memories, (4) attach more value to things than to human beings and (5) are characterized by uncertainty (Ger and Belk, 1996). This behavior and basic belief about life and personal goals has a negative impact on many different variables, such as self-esteem and physical as well as mental well-being (Dittmar et al., 2014; Niemiec et al., 2009; Ryan et al., 1999).

In our model, we place materialism within a self-regulatory perspective (Förster, 2015; for a related model including goal mechanisms see Kasser and Ryan, 1993). Thus, materialism is not only an attitude but it is a motive that triggers goals; such goals can be achieved by certain means.

Materialists are strongly focused on having goals, or possessions that they want to attain using certain means. For example, they can work in order to earn money, they can buy objects, so that they possess them and show them to friends and they can invest in stocks in order to gain even more money. Such means can also include people. Networking is said to be essential in order to make a career and the slime effect (Vonk, 1998) reflects the fact that flattering others in position of power helps one to climb the career ladder, and so-called status friends can be used to show how important one is. More generally, we suggest that materialists have a tendency to view and treat non-material events (like friendships) as a possession (Ger and Belk, 1996; Khanna and Kasser, 2001) or as means to attain their materialistic goals. This is called “objectification” − a process “in which one experiences […] others as objects, commodities or things, rather than as subjects with their own experiences, perspectives and feelings” (Laing, 1969 as cited in Khanna and Kasser, 2001; see Gervais et al., 2013; for a recent approach). Objectification research shows that, under some circumstances, people use other people (e.g., colleagues, friends, relationship partners) to attain their goals, rather than enjoying their company intrinsically. Interestingly, in a yet unpublished paper Khanna and Kasser (2001) suggested and showed that people with high material values tend to objectificate others, use them to reach personal goals and are less empathic and feel less attached to other people. Relatedly, research suggests that materialists also have less stable relationships because they stereotype and manipulate their social environment (Kasser and Kasser, 2001; McHoskey, 1999; Sheldon et al., 2000).

Materialists harness the acquisition of possession and money as a central life goal. They materialize their social environment (i.e., objectification) and use it to reach personal goals, like acquisition and presentation of possession (i.e., instrumentalization). In addition, as mentioned before, materialism is associated with many negative effects, such as a decrease in life satisfaction; such relation was suggested to be mediated by social comparison (Dittmar et al., 2014). Naturally, increasing one’s own status suggests a frame of reference that in the context of acquiring possessions is constantly increasing (Easterlin, 1974; Fromm, 1976).

Typically, the materialists’ goal is not only to acquire sufficient material goods to survive, but rather to outperform significant others (i.e., peers, friends) and to demonstrate higher status. Social standards are likely to be replaced by a higher, more challenging one if a materialistic goal is attained − there is always somebody who is richer than you − making goal fulfillment almost impossible. Failure to obtain the ultimate materialists’ goal would then result in dissatisfaction (see Easterlin, 1974). Consistently, studies could show a significant relationship between social comparison orientation and materialistic values: Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2005) showed that “individuals are happier the larger their income is in comparison with the income of the reference group” (p. 997). Such findings exhibit a mediating link between income (i.e., a materialistic value), happiness and social comparison. Furthermore, in a study by Chan and Prendergast (2007), students in Hong Kong who were more likely to watch commercials on TV compared themselves more with peers; and this connection was found as a significant predictor for materialism.

In the modern world materialism is also connected with media use, so that the consumption of television and commercials is positively associated with materialism (Richins, 1987). Commercials could be a crucial factor for the link between television consumption and materialism because they typically reinforce the notion that the acquisition of specific objects will increase life satisfaction and personal success. They illustrate the materialists’ desired end- state showing that possessions, such as cell phones or cars can provide happiness and success (Dittmar, 2005; Kasser and Kanner, 2004). Consistently, Richins (1987) showed that the link between materialism and the consumption of television is only significant when participants appraised the commercials as realistic and authentic.

Another study with a German sample also investigated the relationship between media consumption, self-esteem, materialism and life satisfaction and confirmed in particular a positive association between materialism and the consumption of media (particularly television; Bak and Keßler, 2011). Thus, this relationship is not confined to certain laboratories or samples, rather it is a more general effect that does exist across cultural backgrounds.

Indeed, not a lot of research has dealt with the relationship between social media, internet use and materialism, and to date not one study has directly investigated the link between Facebook use and materialism. Certainly, Facebook is mainly used for having or attaining friends and, as such, is essentially referring to non-materialistic goals, however, in this study we examine how, dependent on their chronic materialistic values, Facebook users construe friends and friendships and which factors lead to these differences in perception. Specifically, we investigate the relationship between Facebook use and materialism regarding the impacts of social comparison, materialists’ bias for objectification and instrumentalization of their friends and their desire to acquire more “digital” possessions, likewise collecting Facebook friends as digital objects.

1.3. Materialists on Facebook

Based on previous findings concerning the general link between materialism and media use we assume that Facebook use will be positively connected with materialism, so that materialism could yet be another motive for Facebook activity. Considering that materialism is defined as a personality trait and Facebook use as an outcome variable, we assume that materialism is a positive predictor for Facebook use. We state as our first hypothesis:

H1: People with high materialistic values use Facebook more frequently than people with low materialistic values.

Why would this be the case given that SNS are usually produced to facilitate human social interactions? We would like to argue that, for materialists, immaterial events can be used instrumentally to attain their goals. As we mentioned before, friends could be a useful means of attaining success; this can be true for the professional, the interpersonal, but also in the financial domain. To reiterate, studies emphasize that materialists set the acquirement of possessions as a central life goal. In addition, they like to materialize social events such as friendships in order to extend their possessions. One might suggest that materialists extend the number of their Facebook friends because they view them as simple objects that facilitate goal pursuit. More friends would naturally increase Facebook use since users have to organize all the social interactions. Naturally, people pursue goals that are easy to obtain and they prefer means that are highly instrumental for goal fulfillment over less instrumental means − this is true for conscious as well as unconscious motivation (see Förster and Jostmann, 2012; Liberman and Förster, 2008). Facebook seems to be the perfect platform for increasing the number of friends in a very short time, and thus to enlarge their own (digital) possessions efficiently. For materialists, possessions are believed to lead to personal success, and thus Facebook friends who would count as digital possessions, are useful for personal goal attainment. Therefore, our second hypothesis:

H2: The higher peoples’ chronic materialism, the higher their number of Facebook friends (2a) and the higher their tendency to objectificate (2b) and instrumentalize (2c) them in order to reach personal goals.

Our literature review pointed to an important psychological factor for both Facebook use and materialism; namely peoples’ social comparison orientation: Facebook use as well as materialism correlates positively with the tendency to compare oneself to significant others. Such desire can be perfectly satisfied by using Facebook. Online, people have very fast and nearly unrestricted access to millions of comparison-related contents about others via users’ profiles. This also includes access to intimate information about significant others such as details about family and relationships, work and education, as well as certain life events. Hence users are in the position to very easily compare themselves with millions of others. Therefore, our third hypothesis:

H3: The tendency to compare oneself more frequently with others is positively correlated to Facebook use.

Materialistic goal attainment can only be assessed by comparing oneself to a given standard. Naturally, there will always be people who are richer than oneself. Thus, people need to set their own frame of reference in order to define realistic, attainable goals for themselves (Fishbach and Dhar, 2005). Therefore, they need information about what others (i.e., peers, friends or family) possess and to what degree does it compare to their own possessions − information they can receive easily via Facebook. Therefore, our fourth hypothesis:

H4: The higher people’s chronic materialism, the higher their social comparison orientation.

Materialism seems to increase social comparison orientation and to extend objectification and instrumentalization of friends in order to reach personal goals (H2, H4). Social comparison should additionally be associated with a higher Facebook use (H3). As a result, we suggest that materialists use Facebook more frequently because (1) they have more friends, because they use Facebook as medium to (2) objectificate and (3) instrumentalize their online friends and because (4) they use Facebook to satisfy their desire for social comparison to obtain a frame of reference to significant others.

Therefore, we develop a model of Facebook use and materialism which contains the number of Facebook friends, objectification, instrumentalization and the strength of social comparison orientation as mediating factors between the link of materialism and Facebook use. For our fifth hypothesis we propose the following:

H5: Materialists use Facebook more frequently, because they are eager to compare themselves with other users, and have more Facebook friends, whom they can objectificate and instrumentalize.

Altogether with this study, we would like to verify materialism as an additional motive for using Facebook besides the need for self-presentation, the need to belong, and the need for social comparison orientation introducing an explanatory mediation model.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study 1: Pilot

2.1.1. Participants

We recruited participants using a snowball sampling technique through campus-wide emails, flyers and invitations via Facebook (at Ruhr-University of Bochum). Four outliers and two participants with an incomplete dataset were excluded from statistical analysis. This resulted in a final sample of 242 Facebook users (54 males and 188 females) ranging in age between 17 and 52 years with a mean age of 22.91 years (SD = 5.59). The biggest part of the sample was represented by people between 17 and 28 years (90.1%). Most participants had a standard of education equivalent to high school proficiency (86.4%) and were students (97.5%). Participants had around 284 friends on Facebook (M = 284.41, SD = 186.05) with a very high standard deviation.

2.1.2. Design and materials

We created an online survey using the software “EFS Survey”. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were informed that the survey would take no more than 20 minutes. For participation, it was necessary to have an active Facebook account. The survey comprised of a first section for demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, highest degree of education, nationality, native language, relationship status and university course) followed by 62 items to assess Facebook use, Social Comparison orientation, materialism and finally objectification and instrumentalization via Facebook. In order to prevent for order effects, the scales were presented to participants in random order. After passing through the survey we thanked our participants and told them that they could send us an email in case they were interested in the actual results. The ethical committee of the Ruhr-University of Bochum has approved our study proposal.

2.1.3. Instrumentation

For examining the relationships between Facebook use, social comparison orientation, materialism, objectification and instrumentalization we assessed our constructs with the following measurements:

2.1.3.1. Facebook activity

For assessing the Facebook activity we used the Facebook questionnaire created by McAndrew and Jeong (2012) which had been validated and translated into German (Ozimek and Bierhoff, 2016). The questionnaire assesses on a 5-point-Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always) 30 items distributed on three factors, i.e., Watching (11 items; e.g., “I’m looking at other’s relationship status”), Impressing (6 items; e.g., “I’m struggling to decide which profile picture I would like to post) and Acting (13 items; e.g., ‘I’m posting photographs’). The German version showed a good intern consistency for all three dimensions (αwatching = .832, αimpressing = .791, αacting = .765) and also satisfactory construct validity (Ozimek and Bierhoff, 2016). Additionally, participants were asked for the number of their Facebook friends in order to generate a quantitative and demographic variable about Facebook usage. Because validation studies show that the subscales load on a latent second order factor (Ozimek and Bierhoff, 2016), we calculated an overall index of Facebook activity.

2.1.3.2. Social comparison orientation

The social comparison orientation was assessed by the German version of the “Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM)” (Schneider and Schupp, 2011), which was originally created by Gibbons and Buunk (1999). The items refer to general interest in social comparison with others. The INCOM consists of two subscales named Ability (6 items; e.g., “I often compare how I am doing socially”) and Opinion (5 items; e.g., “I always like to know what others in a similar situation would do”). The response scale of the 11-items questionnaire ranges from “I do not agree” (1) to “I fully agree” (5). The German version has high validity and reliability (α = 0.7–0.85; Schneider and Schupp, 2011). Because validation studies show that both subscales are positively correlated with each other (Gibbons and Buunk, 1999), we calculated an overall index of social comparison orientation.

2.1.3.3. Materialism

We measured materialism using the German version of the Material Value Scale (MVS-G; Müller et al., 2013). The original version was created by Richins and Dawson (1992). The MVS-G consists of 15 items and assesses on a 5-point-Likert scale the materialistic attitudes of participants in two dimensions, i.e., “Acquisition As The Pursuit Of Happiness” (e.g., “My life would be better if I owned certain things I don’t have.”) and “Acquisition Centrality/Possession-Defined Success‘ (e.g., " I usually buy only the things I need.’; “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes.”). The response scale of the 15-items questionnaire ranges from “I strongly disagree” (1) to “I strongly agree” (5). Validity and reliability (α= 0.89) have been proved (Müller et al., 2013). Because validation studies show that both subscales are positively correlated with each other (Richins and Dawson, 1992), we calculated an overall index of materialism.

2.1.3.4. Objectification of Facebook friends

We developed a one-item-question to assess the participants’ manifestation regarding objectification of their Facebook friends. We used a former study by Fitzsimons and Shah (2008) as a basis for the development of our objectification measure. Participants were asked on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = applies fully to 5 = does not apply at all) to quantify how useful their Facebook friends are in reaching private or professional success. The original item was: “Having many Facebook friends contributes more success in my personal and professional life.”.

2.1.3.5. Instrumentalization of Facebook friends

A second one-item-question was generated to assess participants’ manifestation to use their Facebook friends as instruments for reaching personal goals. Participants were asked on a 7-point-Likert scale (from 1 = not helpful to 7 = very helpful) if their Facebook friends are helpful to reach personal goals. The original item was: “To what extent do you think Facebook friends are useful in order to attain your goals?”.

2.1.4. Results

2.1.4.1. Preliminary analysis

In this study Cronbachs alpha coefficients were determined to verify that all scales were internally consistent (α > .70; Nunnally, 1978). All scales reached good reliability coefficients: i.e., for the Facebook activity scale α = .871, for the INCOM α = .863 and for the Material Value Scale α = .827.

2.1.4.2. Validating objectification and instrumentalization of Facebook friends

As a first approach in order to validate the new one-item measures for objectification and instrumentalization, we correlated both measures with materialism and its subscales (cf. Table 1) because we our literature review suggests that they might have common variance (cf. Ger and Belk, 1996). In fact, results reveal that both objecitification and isntrumentalization are positively correlated to materialism and its subscales. Thus, this could be a first hint in order to validate these measures.

Table 1.

Full correlation matrix of the used measures (Study 1).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB-Watching (1) | _ | ||||||||

| FB-Impressing (2) | .459*** | _ | |||||||

| FB-Acting (3) | .399*** | .324*** | _ | ||||||

| CO-Ability (4) | .387*** | .266*** | .145* | _ | |||||

| CO-Opinion (5) | .237*** | .261*** | .162* | .552*** | _ | ||||

| MVS-Centrality/Success (6) | .251*** | .129* | .232*** | .293*** | .137* | _ | |||

| MVS-Happiness (7) | .314*** | n.s. | .182** | .346*** | .152* | .599*** | _ | ||

| Objectification (8) | .371*** | .169** | .341*** | .213** | n.s. | .310*** | .284*** | _ | |

| Instrumentalization (9) | .284*** | n.s. | .268*** | n.s. | n.s. | .233*** | .152* | .422*** | _ |

Note. FB = Facebook, CO═Comparison Orientation, MVS = Material Value Scale. dfs = 240. *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001; n.s. = not significant.

Table 1 displays the correlations of all measures and subscales. It is obvious that nearly all scales are positively associated with each other except for Facebook-Impressing, MVS-Happiness and Instrumentalization, CO-Ability and Instrumentalization and CO-Opinion, Objectification and Instrumentalization.

2.1.4.3. Evaluation of hypotheses

Altogether, all hypotheses can be classified as correlation hypotheses that were tested as follows via correlation analyses.

H1: People with high materialistic values use Facebook more frequently than people with low materialistic values.

With regards to the core hypothesis a product moment correlation revealed a significant positive correlation between Facebook activity and materialism (r (241)= .286, p < .001).

H2: The higher people’s chronic materialism, the higher their amount of Facebook friends (2a) and the higher their tendency to objectificate (2b) and instrumentalize (2c) them in order to reach personal goals.

The conduct of a correlation analysis between materialism, amount of Facebook friends (r (241)= .158, p < .05), objectification (r (241)= .305, p < .001) as well as instrumentalization (r (241)= .221, p < .01) enabled the validation of the second hypothesis.

H3: The tendency to compare oneself more frequently with others is positively correlated to Facebook use.

With reference to the results of the correlation analysis, a significant positive correlation between social comparison and Facebook activity was found (r (241)=.374, p < .001).

H4: The higher people’s chronic materialism, the higher their social comparison orientation.

Likewise, the provision of correlation analysis was able to show a significant positive correlation between materialism and social comparison (r (241)=.307, p < .001).

H5: Materialists use Facebook more frequently, because they are eager to compare themselves with other users, and have more Facebook friends, whom they can objectificate and instrumentalize.

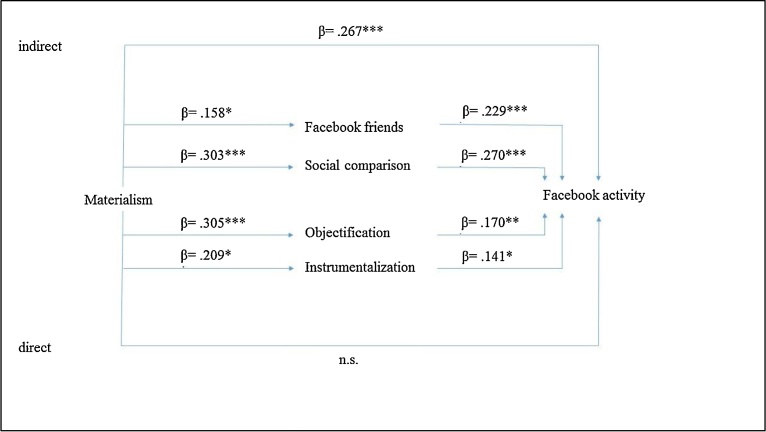

This hypothesis presupposes a multiple mediation to examine whether the association between materialism and frequency of Facebook use can be mediated completely through social comparison, objectification and instrumentalization of Facebook friends, as well as the amount of the latter. In order to do so, a mediation analysis by means of a script named ‘INDIRECT’ composed by Preacher and Hayes (2008) was calculated which fundamentally applies an OLS-regression method. The mediation analysis is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Association between materialism and Facebook activity mediated by social comparison orientation, objectification, instrumentalization and the number of Facebook friends in Study 1. Note. The mediation model is significant with F5,236 = 18.364, adjusted R2= .265. *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001; n.s.= not significant.

Fig. 1 portrays the direct and indirect pathways as well as standardized regression coefficients of the mediation model. Therefore, it can be noted that materialism can predict the amount of Facebook friends, social comparison, objectification and instrumentalization, and that these variables in turn appear as mediators predicting the frequency of Facebook use. Since only the indirect pathway of materialism to Facebook use became significant via the mediators, the mediation can be classified as a complete mediation, which explains 26.5% of total variance. By adding gender and level of education as possible covariates, no significant effect revealed (p > .05). Additional calculation of bootstrapping confidential intervals (m = 1000) reveal significant effects for all proposed mediators, i.e., for the number of Facebook friends CI95 = [.007; .084], for social comparison orientation CI95 = [.042; .141], for objectification CI95 = [.019; .108] and for instrumentalization CI95 = [.006; .071].

Hence with reference to the results of the two-step mediation analysis, our hypothesis H5 can be affirmed showing that the association between materialism and Facebook activity can be partly explained by the fact that materialists display a stronger social comparison orientation, have more Facebook friends and objectify as well as instrumentalize them more intensely.

2.1.5. Discussion

Altogether, our results show that all five hypotheses can be confirmed. With confirmation of the basic hypothesis (H1) we could show that materialism and Facebook use are positively connected. The results indicate that social networking sites such as Facebook could be a medium to satisfy materialistic requirements, such as the presentation of one’s own possessions, comparing one’s own goods with others’ or the extension of (digital) possession.

Additional correlational analyses between the subscales of the materialism questionnaire and specific Facebook scales (see Table 1; Table 2) indicate that both subscales “Happiness” and “Centrality/Success” are associated with Facebook-Watching, −Acting, and −Impressing. Only Happiness and Facebook-Impressing have no significant link.

Table 2.

Full correlation matrix of the used measures (Study 2).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB-Watching (1) | _ | ||||||||

| FB-Impressing (2) | .426*** | _ | |||||||

| FB-Acting (3) | .474*** | .472*** | _ | ||||||

| CO-Ability (4) | .299*** | .160** | .152** | _ | |||||

| CO-Opinion (5) | .232*** | .188** | n.s. | .662*** | _ | ||||

| MVS-Centrality/Success (6) | .185** | n.s. | .141* | .195** | .151* | _ | |||

| MVS-Happiness (7) | .276*** | .198** | .123* | .220*** | .153** | .228*** | _ | ||

| Objectification (8) | .173** | .195** | .348*** | .124* | .144* | .221*** | n.s. | _ | |

| Instrumentalization (9) | .229*** | .213 | .316*** | .172** | .162** | .225*** | n.s. | .446*** | _ |

Note. FB = Facebook, CO═Comparison Orientation, MVS = Material Value Scale. dfs = 240. *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001; n.s. = not significant.

For explaining this outcome we tested a mediation model showing that social comparison, objectification, instrumentalization and the amount of Facebook friends mediated the relationship between materialism and Facebook use. Thus, via Facebook, people seem to compare themselves and their possession with others, and objectify and instrumentalize their Facebook friends, representing and extending the amount of their possessions. In other words, Facebook friends could be used as kind of digital possessions, or as means that can further enable materialistic goal pursuit. Notably, these results are congruent to former findings showing that materialists use their friends for reaching external goals (Khanna and Kasser, 2001). We show in the current study that Facebook constitutes a very good platform for satisfying these motives.

Note that the sample of our study makes it difficult to generalize the results: Our sample consisted of mainly young female psychology students between 17 and 28 years old. Needless to say, using psychology students who are sensitive to research questions might bias results. To attain a more generable sample, we replicated our mediation model in a second study by recruiting a more unbiased sample.

2.2. Study 2: Replication

2.2.1. Participants

In order to replicate the mediation model, we recruited participants for our study using flyers and invitations via Facebook (at Ruhr-University of Bochum). Three participants with an incomplete dataset were excluded from statistical analysis. This resulted in a final sample of 289 Facebook users (113 males and 176 females) ranging in age between 17 and 64 years with a mean age of 26.21 years (SD = 8.87). Most participants had a standard of education equivalent to high school proficiency (64.0%) and were students (60.6%). Participants had around 318 friends on Facebook (M = 318.15, SD = 242.94) with a very high standard deviation.

2.2.2. Design and materials

In order to replicate our model, we used the same procedure and the same measures as in Study 1. To prevent order effects, the scales were presented to participants in random order. The ethical committee of the Ruhr-University of Bochum has approved our study proposal.

2.2.3. Results

2.2.3.1. Preliminary analyses

For all used scales we calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for assessing the intern consistency. All scales reached good reliability coefficients: i.e., for the Facebook activity scale α = .895, for the INCOM α = .852 and for the Material Value Scale α = .879.

2.2.3.2. Validating objectification and instrumentalization of Facebook friends

Results reveal positive correlations between instrumentalization, objectification, the materialism overall index and the subscale “centrality/success”. The correlations between objectification, instrumentalization and the subscale “happiness” are merely positive, but not significant (cf. Table 2). Thus, in Study 2, we could partially replicate our validation.

2.2.3.3. Correlational analyses

We calculated correlation coefficients in order to replicate our findings regarding H1-H4. In fact, analyses reveal that materialism is positively correlated to Facebook usage (r (289) = .257, p <.001; H1), to the number of Facebook friends (r (289) = .125, p <.05; H2a), to Objectification (r (289) = .169, p <.01; H2b) and Instrumentalization (r (289) = .203, p <.01; H2c). Social comparison orientation is positively correlated to both Facebook use (r (289) = .263, p <.001; H3) and materialism (r (289) = .256, p <.001; H4). Thus, hypotheses 1–4 can be confirmed again. The correlations of all subscales are depicted in Table 2.

2.2.3.4. Mediation

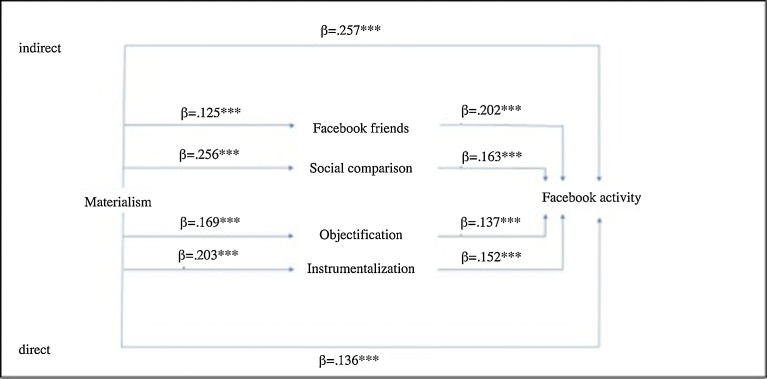

In order to replicate our model we again used a two-step mediation analysis, calculating an OLS-regression model and bootstrapping confidential intervals by using the SPSS macro INDIRECT (Hayes, 2012). The results of the OLS-regression are depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Association between materialism and Facebook activity mediated by social comparison orientation, objectification, instrumentalization and the number of Facebook friends in Study 2. Note. The mediation model is significant with F5,286 = 16.088, adjusted R2= .208. *p < .05 **p < .01 ***p < .001.

Fig. 2 shows that all pathways from the independent variable to the mediators and also from the mediators to the dependent variable are significant. Also the direct path from materialism to Facebook activity and the indirect path via the mediators show significant regression weights. Thus, the analysis revealed a partially fulfilled mediation. By adding gender and level of education as possible covariates, no significant effect revealed (p > .05). Additional calculation of bootstrapping confidential intervals reveal significant effects for all proposed mediators, i.e., for the number of Facebook friends CI95 = [.067; .190], for social comparison orientation CI95 = [.011; .084], for objectification CI95 = [.002; .066] and for instrumentalization CI95 = [.007; .072].

2.2.4. Discussion

The two-way mediation analysis replicated our postulated mediation model which proposed that people who scored high in materialism use Facebook more intensely because they have a higher social comparison orientation, they have acquired more Facebook friends and they use Facebook more as a way to objectify and instrumentalize their digital friends. Thus, the finding from study 1 was replicated also with a more unbiased sample with fewer students and more male participants.

3. Discussion & conclusion

By conducting two online-surveys we could show that materialism is positively correlated with Facebook use and that its relationship can partially be explained by four mediators, i.e., social comparison orientation, amount of Facebook friends and the objectification and instrumentalization of them.

More generally, it seems to us that materialism is able to act as an additional motive for using Facebook. As narcissists use Facebook for self-glorification, or people with low self-esteem for interacting with others and feeling better, materialists use it to acquire and promote possessions. In a more general way of interpretation, we can outline that Facebook serves as a method to satisfy trait-dependent needs and to self-regulate.

3.1. Deriving a self-regulatory model of SNS use

If we put together the evidence of our own and various former studies, it becomes clear, that Facebook is associated with self-esteem, social comparison, traits of personality (i.e., materialism and narcissism), and impression management or personal well-being. More generally, from a self-regulatory perspective (Higgins, 1997) people simply want to approach positive end states and to avoid negative end states (Carver and Scheier, 1982), reflecting an underlying hedonic principle. Likewise, Facebook could serve as a medium for self-regulation, i.e., a process for controlling and leading one’s own behavior in order to reach desirable thoughts, positive affect and personally relevant goals (Carver and Scheier, 1982).

It appears to us that Facebook is a very attractive, simple and fast medium for experiencing positive affect, due to its possibilities for positive self-presentation: People are able to present themselves as positively as possible with the help of status updates, their profiles and photographs (Gonzales and Hancock, 2011) and receive via “likes” and the commentary function immediate (mostly positive) feedback for feeling better and being more self-confident. The negative correlation between self-esteem and Facebook in former studies might indicate that people with low self-esteem use Facebook because they hope to receive positive feedback while posting photographs, to have a higher chance to extend their number of online-friends and so to get more connected with other people. Consistent with this idea, studies show that people with low self-esteem have a very strong desire to be a part of the “Facebook society”, and they post many different topics to engage with others (Hollenbaugh and Ferris, 2014; Tazghini and Siedlecki, 2013). Moreover, the need to belong could already be identified as basic motives for Facebook use (Nadkarni and Hofmann, 2012). Thus it seems that users are trying to improve their self-esteem in various interpersonal and individual domains, although it is unclear whether such attempts are always successful or if this is simply a construct motivating users to go online (Ellison et al., 2007; Valkenburg et al., 2006). Finally, it seems very obvious that the high number of Facebook users provides the perfect and simple possibility for various aligned social comparisons via reading and commenting users’ profiles.

Based on our conclusions, we aim to derive and implement a Theory of Social Online Self-Regulation (SOS-T), focusing on the motives, goals, and desired end-states that might drive Facebook use and the means that are involved. Facebook may be an exemplar for social online-media use providing us with an excellent database for research to study underlying processes of self-regulation. Thus, we argue that Facebook can be used for self-regulation, serving as a means to attain a variety of goals (self-esteem, social interaction, materialistic goals, self-presentation, etc.), ultimately enabling the attainment of hedonically positive end states.

What would be the added value of a self-regulatory approach? In the recent past, self-regulatory models helped to increase our understanding in a variety of domains such as health (Leventhal et al., 1998), consumers’ behavior (Avnet and Higgins, 2006), decision making (Latham and Locke, 1991), and intergroup behavior (Sassenberg and Woltin, 2008), to name but a few. An advantage of self-regulation approaches may be the involvement of well-established variables (or “principles”, see Förster et al., 2007) that drive behavior in many life domains and thus place certain aspects of human life into more general and integrative frameworks.

Some of these variables may be interesting for the study of SNS: To illustrate, self-regulation depends on the value of the means and the goals, expectancies to be successful during goal pursuit (see Fishbein and Ajzen, 1974; Förster et al., 2007; Liberman and Förster, 2008), the idea of alternative means to reach the same goal (equifinality see Kruglanski et al., 2002) and the attractiveness of means that serve multiple goals (multifinality; see Kruglanski et al., 2002; 2013). From this perspective, Facebook is a means with high multifinality (satisfying multiple goals), has high value (e.g., it is popular, it is highly frequented by peers), and it involves a high expectancy of success (e.g., it is priceless, easy to reach and to handle, and the likelihood of getting many “likes” is generally high). One may reason then, that alternative SNSs need to compete with these features. Thus they need to gain similar value, should enable a similar likelihood of success, and need to meet a similarly high multifinality.

One might question whether Facebook consumption really makes us happy or whether this remains a mere illusion − such questions should also be addressed in future research. Related to our study one might, in addition, test, whether Facebook friends on the long run can indeed be useful professionally. From other research on self-regulation we expect person-situations interactions − and thus the question for whom Facebook is useful and in which situation could it be relevant. Our study points to such interactions showing that, for materialists, Facebook offers some added value.

Furthermore, self-regulation theories could also produce new predictions. For example, relaxation upon goal fulfillment was observed repeatedly (so called Zeigarnik-effects; see Denzler et al., 2009). Would Facebook consumption then reduce the desire to use it for a certain time if the ultimate goal, i.e., happiness, has been reached? Intuitively, one might lose interest in SNS, when happy (e.g., because one is in love, becomes a father, is successful in business, etc.). Related to our study, would extensive Facebook use be reduced when a materialist’s goals are attained?

3.2. Limitations

There are some limitations regarding our design of study so that we need future studies that are able to offset these limitations.

First, the used survey technique is only able to capture human feelings and behavior retrospectively. Questionnaires require a high level of participants’ ability to evaluate themselves regarding their social comparison orientation, their materialism or the frequency of Facebook activities which they have recently performed. Thus, data can be subjectively biased by overestimation of participants’ memory performance and ability of self-evaluation (Fahrenberg et al., 2007; Pohl, 2004). Additionally, standardized questionnaires, as we used in our study, provide more objective measurements but are limited by a loss of information compared to qualitative methods (Bortz and Döring, 2006). Thus, quantitative data may not be sufficient to probe the true feelings of the participants.

Future studies should, therefore, use other methods of measurements and design of study. For example Fahrenberg and colleagues (2007) propose ambulatory assessments as an alternative to retrospective surveys. These are computer-based assessment methods that can be programmed in mobile devices. With ambulatory assessments it could be possible to create an application for mobile devices such as smartphones which could ask users several times a day to answer a short questionnaire for Facebook use and case variables. In this way, it could be assessed how people are using Facebook in certain situations. It could also be assessed if materialistic activities (e.g., shopping) are immediately connected with the desire to share these activities on Facebook.

A second possibility for a widespread insight of materialistic Facebook use could be the use of a combined method assessing both quantitative data by surveys and qualitative data by attending in-depth interviews so that the qualitative source (interview findings) can be used to triangulate the survey findings.

Second, because of the correlational nature of our study, no causal direction can be asserted. The realized regression and mediation only declare that the idea of regression or mediation is compatible with the assessed data. Thereby it is possible that independent variables act as dependent variables or as additional mediators, so that there are various possibilities to construct a mediation model (Fiedler et al., 2011; Hayes, 2013).

Contrary to our statements based on our mediation model (Fig. 1; Fig. 2), it is also possible that a frequent Facebook use leads to more materialistic values and that this is the reason why Facebook users are more likely to objectificate and instrumentalize their friends: The enhanced confrontation with high social standards on Facebook could activate materialistic thoughts and motivate users to question themselves with regard to their success in acquiring possessions. Viewing status updates by others, such as a new photo of a friend presenting his newly bought luxury articles for example, may increase materialistic desires. A high frequency of Facebook use could then lead to a materialistic attitude including the notion that having a lot of possessions and presenting them in terms of impression management on Facebook are the main goals for holding and heightening social status. Additionally, Facebook is often used as an advertising surface for different brands which may further reinforce materialism.

However, even though all this could be true (see Richins, 1987), we suggest that materialism as a rather stable personality trait could cause Facebook use because it is an efficient means to satisfy basic motives such as social comparison and acquiring digital posessions.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Phillip Ozimek, Fiona Baer, Jens Förster: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Pude for revising and improving our writing style and language.

References

- Avnet T., Higgins E.T. How regulatory fit affects value in consumer choices and opinions. J. Mark. Res. 2006;43(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Back M.D., Stopfer J.M., Vazire S., Gaddis S., Schmukle S.C., Egloff B., Gosling S.D. Facebook Profiles Reflect Actual Personality, Not Self-Idealization. Psychol. Sci. 2010;21(3):372–374. doi: 10.1177/0956797609360756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak P.M., Keßler T. Materialismus, Selbstwert, Lebenszufriedenheit und Mediennutzung. J. Bus. Media Psychol. 2011;2(2):29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz J., Döring N. Springer; Heidelberg: 2006. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation: Für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D.M. 4th edition. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 2012. Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. [Google Scholar]

- Carver C.S., Scheier M.F. Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychol. Bull. 1982;92(1):111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K., Prendergast G. Materialism and social comparison among adolescents. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2007;35(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Denzler M., Förster J., Liberman N. How goal-fulfillment decreases aggression. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009;45(1):90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar H. Compulsive buying −a growing concern? An examination of gender, age, and endorsement of materialistic values as predictors. Br. J. Psychol. 2005;96(4):467–491. doi: 10.1348/000712605X53533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar H., Bond R., Hurst M., Kasser T. The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2014;107(5):879. doi: 10.1037/a0037409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin R.A. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In: David P.A., Reder M.W., editors. Nations and households in economic growth. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1974. pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook ‘friends’: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenberg J., Myrtek M., Pawlik K., Perrez M. Ambulantes Assessment −Verhalten im Alltagskontext erfassen. Psychologische Rundschau. 2007;58(1):12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell A. Income and well-being: an empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. J. Pub. Econ. 2005;89(5):997–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler K., Schott M., Meiser T. What mediation analysis can (not) do. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011;47(6):1231–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Attitudes toward objects as predictors of single and multiple behavioral criteria. Psychol. Rev. 1974;81:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A., Dhar R. Goals as excuses or guides: The liberating effect of perceived goal progress on choice. J. Consum. Res. 2005;32(3):370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons G.M., Shah J.Y. How goal instrumentality shapes relationship evaluations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008;95(2):319. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster J. Pattloch; München: 2015. Was das Haben mit dem Sein macht. Die neue Psychologie von Konsum und Verzicht. [What having does to being. The new psychology of consume and self-control] [Google Scholar]

- Förster J., Jostmann N. What is automatic self-regulation? Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 2012;220(3):147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Förster J., Liberman N., Friedman R. Seven principles of goal activation: A systematic approach to distinguishing goal priming from priming of non-goal constructs. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2007;11:211–233. doi: 10.1177/1088868307303029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag; München: 1976. Haben oder Sein: Die seelischen Grundlagen einer neuen Gesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Ger G., Belk R.W. Cross-cultural differences in materialism. J. Econ. Psychol. 1996;17(1):55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S.J., Bernard P., Klein O., Allen J. Objectification and (De) Humanization. Springer; New York: 2013. Toward a unified theory of objectification and dehumanization; pp. 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales A., Hancock J. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-Esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011;14(1-2):79–83. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons F.X., Buunk B.P. Individual Differences in Social Comparison: Development of a Scale of Social Comparison Orientation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999;76(1):129–142. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford Press; New York: 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997;52(12):1280. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbaugh E.E., Ferris A.L. Facebook self-disclosure: Examining the role of traits, social cohesion: and motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;30:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T., Kanner A. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2004. Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T., Kasser V.G. The dreams of people high and low in materialism. J. Econ. Psychol. 2001;22(6):693–719. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T., Ryan R.M. A dark side of the American dream: correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993;65(2):410. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S., Kasser T. Materialism, objectification, and alienation: A cross-cultural investigation of U.S., Indian, and Danish college students. Unpublished manuscript. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Krämer N.C., Winter S. Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. J. Media Psychol. Theories Method. Appl. 2008;20(3):106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski A.W., Shah J.Y., Fishbach A., Friedman R., Chun W., Sleeth-Keppler D. A theory of goal systems. In: Zanna M.P., editor. Vol. 34. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego, CA, US: 2002. pp. 331–378. (Advances in Experimental Social Psychology). [Google Scholar]

- Kruglanski A.W., Köpetz C., Bélanger J.J., Chun W.Y., Orehek E., Fishbach A. Features of multifinality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2013;17(1):22–39. doi: 10.1177/1088868312453087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing R.D. Random House; New York: 1969. The divided self. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.Y. How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites? The case of Facebook. Comput. Human Behav. 2014;32:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Latham G.P., Locke E.A. Self-regulation through goal setting. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50(2):212–247. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H., Leventhal E.A., Contrada R.J. Self-regulation, health, and behavior: A perceptual-cognitive approach. Psychol. Health. 1998;13(4):717–733. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman N., Förster J. Expectancy: value and psychological distance: A new look at goal gradients. Soc. Cogn. 2008;26:515–533. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew F.T., Jeong H.S. Who does what on Facebook. Age, sex, and relationship status as predictors of Facebook use. Comput. Human Behav. 2012;28(6):2359–2365. [Google Scholar]

- McHoskey J.W. Machiavellianism, intrinsic versus extrinsic goals, and social interest: A self-determination theory analysis. Motiv. Emot. 1999;23(4):267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdizadeh S. Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010;13(4):357–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A., Christofides E., Desmarais S. More Information than You Ever Wanted: Does Facebook Bring Out the Green-Eyed Monster of Jealousy? CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009;12(4):441–444. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A., Smits D.J., Claes L., Gefeller O., Hinz A., de Zwaan M. The German version of the Material Values Scale. GMS Psycho. Soc. Med. 2013;10:1–10. doi: 10.3205/psm000095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A., Hofmann S.G. Why do people use Facebook? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2012;52(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec C.P., Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. The path taken: Consequences of attaining intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations in postcollege life. J. Res. Pers. 2009;43(3):291–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J.C. 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1978. Psychometric theory. [Google Scholar]

- Ozimek P., Bierhoff H.W. Facebook use depending on age: The influence of social comparisons. Comput. Human Behav. 2016;61:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl R.F., editor. Psychology Press; New York: 2004. Cognitive illusions. A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgment and memory. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Met. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L. Media, materialism, and human happiness. Adv. Consum. Res. 1987;14(1):352–356. [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L., Dawson S. A Consumer Values Orientation for Materialism and Its Measurement: Scale Development and Validation. J. Consumer. Res. 1992;19(3):303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R.M., Chirkov V.I., Little T.D., Sheldon K.M., Timoshina E., Deci E.L. The American dream in Russia: Extrinsic aspirations and well-being in two cultures. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999;25(12):1509–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S., Schupp J. The Social Comparison Scale: Testing the Validity, Reliability, and Applicability of the Iowa-Netherlands Comparison Orientation Measure (INCOM) on the German Populatio. DIW Data Documentation. 2011 (360) [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon K.M., Sheldon M.S., Osbaldiston R. Prosocial values and group assortation. Human Nat. 2000;11(4):387–404. doi: 10.1007/s12110-000-1009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfield C., Ellison N.B., Lampe C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008;29(6):434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Tazghini S., Siedlecki K.L. A mixed method approach to examining Facebook use and its relationship to self-esteem. Comput. Human Behav. 2013;29(3):827–832. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J., Schouten A. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well being and social self-esteem. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2006;9(5):584–590. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonk R. The slime effect: Suspicion and dislike of likeable behavior toward superiors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998;74(4):849. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.E., Gosling S.D., Graham L.T. A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012;7(3):203–220. doi: 10.1177/1745691612442904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]