Abstract

The acknowledgment that specialization in neurology based on a clinician's extensive background in neuroscience contributes to expertise in patient care was a motivating factor in developing neurology residency programs. The increasing demand for more and better access to neurologic care has created a health care environment ripe for innovation. Advanced practice providers currently do not have the opportunity during primary training to gain much experience in neurologic care. We discuss the challenges and benefits of developing a 1-year neurology residency program for nurse practitioner and physician assistant graduates at our institution. We propose that providing advanced practice providers with specialty skills through neurology residency programs such as ours will be integral to meet the growing clinical need for neurologic care.

The availability of neurology providers to accommodate the numbers of patients in need is inadequate and is going to become more so over the next decade.1 Our neurology practice at Duke University Health System has benefitted from using advanced practice providers (APPs) in outpatient and inpatient settings. Both nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) work in our practice and receive competitive pay and benefits. APPs working in the neurology outpatient clinic primarily see return patients and work in tandem with neurologists seeing new patients, particularly if an urgent referral is needed. On the inpatient side, APPs work alongside resident house staff, with faculty, or independently depending on the service model.

We have attempted to integrate APPs into our practice to extend care to more patients: faculty can spend more time seeing new patients while neurology APPs see return patients. This model has not been wholly successful, in part because of education challenges faced by neurology APPs. Most NP and PA programs have limited, if any, clinical neurology training. The training that does occur is often limited with respect to didactic and clinical exposure. Even when training in neurologic physical diagnosis and disease is provided in these programs, APPs rarely learn to “think like a neurologist” (i.e., gain the skill to fully localize a lesion, formulate the presentation, and develop a differential diagnosis with a resultant plan for tests and treatment). Much of the first year of a traditional MD neurology residency is dedicated to developing this process and a fundamental knowledge base about diagnosis and disease.

Because of this educational deficiency, APPs in our practice often have months of onboarding to gain the understanding needed to care for patients. If APPs work within a subspecialty, they likely gain comfort around that subspecialty. However, when their patient returns with a new neurologic issue affecting a different area, they feel inadequate to fully address the problem, leading to an additional neurology referral and complicating the access issue again. Assessment of the APP's knowledge base and neurologic approach to patients is critical to developing trust between the APP and supervising neurologist.

In response to this challenge, we started a 1-year neurology residency for postgraduate APPs in order to develop a better educated and prepared cadre of neurology APPs. We relied on the educational strength of a faculty dedicated to resident and fellow training as well as the enthusiasm of our own APPs who never themselves had this opportunity but consider teaching an important part of their mission.

We overcame several obstacles while starting this program. Unlike medical postgraduate training, no trainee license was available from our state medical board. Therefore, we had to credential our neurology APP residents as providers, which created some confusion among faculty and administrative personnel. Although some APP residencies in other areas have used billing capabilities of APPs to offset their salary/benefit costs, we felt strongly that our APP residents should not bill because they would always be supervised by a faculty neurologist or supervising senior APP. We felt it was appropriate to pay them at a PGY1 level because an NP or PA graduate degree was the prerequisite for application. Some felt that no APPs would want to pass up the additional salary that they would have garnered if they had had a regular position. We found just the opposite.

The APP resident applicants had a true interest in neurology and saw this year of training as an investment in their future. We also emphasized that the APP resident graduate would have a unique skill set applicable to additional involvement in neurologic education and research. Our neurology APP residents are paid for by resources from both our department and our hospital. We made certain that the volume of patients seen by the neurology APP residents did not dilute the exposure for our neurology residents and fellows. Because of our volume of patient care as well as the ability to have neurology APPs precepted by our senior APPs, this did not present a problem.

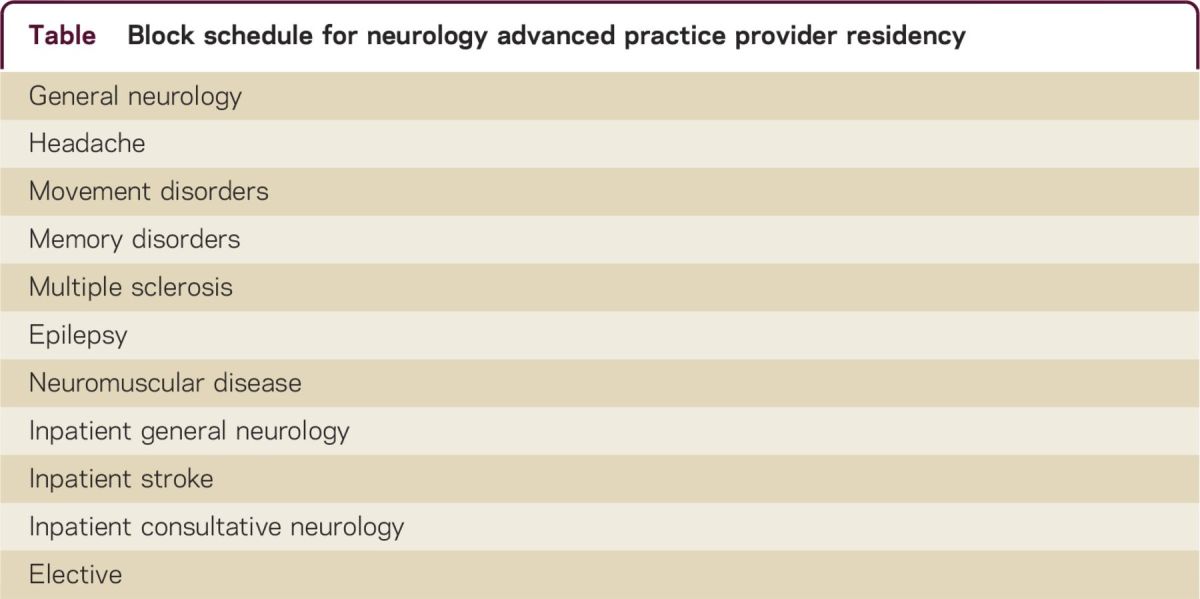

We constructed our neurology APP residency program on a monthly rotation schedule (see table). We asked for a neurology faculty member and, if present, a senior APP on the particular service to act as rotation coordinator for each rotation. Our goal was for the neurology APPs to spend two-thirds of their time with faculty and one-third of their time with the senior APPs on that service. This would allow complementary education about disease, practice mechanics, and professionalism. We developed a curricular outline of common topics to be covered during each rotation. Physical diagnosis was emphasized, with the goal of having the neurology APP residents evaluate as many patients as possible and then present to their supervisor. Each neurology APP resident was given an average of 60 minutes for a new patient evaluation and 30 minutes for a return visit, the same intervals we suggest for PGY2 neurology residents. The volume of patients seen by our neurology APP residents was slightly lower overall than that of our PGY2 neurology residents, depending on the residents. The first rotation was in general neurology and emphasized common chief complaints and the mechanics of our documentation system. Didactics were piggybacked on the shoulders of our neurology residency program core lecture series. Issues of Continuum® that paralleled the monthly rotations were loaned to each resident to provide a useful reading source of core material. We also asked residents to read basic texts on neuroanatomy. Full support of our department chair and residency program director was crucial to development of this program. In addition, neurology APP residents met weekly with one of the program directors to review questions about care, learning objectives, and professionalism. Rotation evaluations were filled out by supervising faculty and senior APPs and were organized around the core competencies.

Table.

Block schedule for neurology advanced practice provider residency

The organizational scheme for the neurology APP residency program is similar to a PGY2 experience for our neurology residents. Our PGY2 neurology residents are successfully prepared to evaluate common neurologic presentations in both outpatient and inpatient settings. Our practice needs for APPs span our entire practice. Preference for acceptance to our neurology APP residency program was given to those able to commit to possible hiring into a permanent position at the completion of training. Our current class of neurology APP residents is our first class, and they are committed to joining our department after residency. Given the considerable investment of time and resources by the faculty, department, and hospital, our hope is that these trainees will have immediate clinical productivity after completion. Ultimately, we believe that other institutions will see the merit of this approach to the development of APP neurology clinicians. The American Academy of Neurology is embracing the participation of APPs in neurology, and this will further the graduates' ability for lifelong learning.2

Although some APP graduates still prefer to enter directly into the workforce for a number of reasons (particularly financial), our early interactions with those training in NP and PA programs at Duke suggest that a large percentage are looking for postgraduation specialty training opportunities. Our program is new, but eventually we hope to compare productivity and patient satisfaction scores of the neurology APP resident graduates we hire to other neurology APPs who have joined us without residency experience. As with all residency positions, funding for a truly educational experience is complicated. Our hope is that neurology practices and hospitals will want to make the investment because the productivity and retention of neurology residency–trained APPs will be better than those without specialty training. That concept will need to be studied. Future challenges of neurology APP resident training also include formal testing to demonstrate the knowledge base for trainees. Next year we will integrate the supervised patient examinations for each rotation to parallel those done for the neurology residents as part of their board requirements. Ultimately, a neurology APP certification examination may be beneficial. Moreover, it would be beneficial if payment systems took into account the additional training of APPs who do specialty residencies.

The time is now for neurologists to formally train a legion of neurology APPs to facilitate care for patients, improve our education of NPs and PAs in neurology, and expand our neurology research portfolio. What are we waiting for?

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr. Kevin Sowers, CEO, Duke Hospital and Dr. Richard O'Brien, Chair, Department of Neurology for their support of this program.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Joel C. Morgenlander: program conception, design, financial support. Robert Blessing: program support, manuscript editing.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

J. C. Morgenlander has served as a consultant to the National Football League; receives research support from Biogen Idec; and holds stock/stock options in Zinfandel Pharmaceuticals, Inc. R. Blessing reports no disclosures. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology 2013;81:470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwarz HB, Fritz JV, Govindarajan R, et al. Neurology advanced practice providers: a position paper of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurol Clin Pract 2015;5:333–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]