Key Points

Incidence of MM has increased in recent years in the United States with a tendency for younger age at diagnosis.

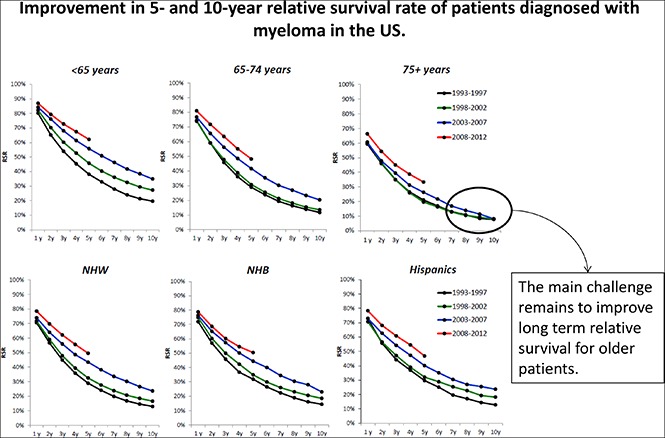

Five- and 10-year survival of MM patients is improving among racial/ethnic minorities, but remains limited in patients ≥75 years of age.

Abstract

Prior improvements in multiple myeloma (MM) survival were not fully observed in racial and ethnic minorities and older individuals. We hypothesized that improvements in MM management in recent years have reduced these disparities. We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries to calculate the incidence and relative survival rates (RSRs) of MM in the United States for patients diagnosed from 1993 to 1997 (prethalidomide), 1998 to 2002 (introduction of thalidomide), 2003 to 2007 (bortezomib and lenalidomide), and 2008 to 2012 (upfront bortezomib and lenalidomide, early availability of carfilzomib and pomalidomide). MM incidence increased significantly among non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) and non-Hispanic black (NHB) men, but not among NHB women and Hispanics. Improvement in 5-year RSRs (1993-1997 vs 2008-2012) was seen among patients of all age and race/ethnicity groups. Ten-year RSRs (1993-1997 vs 2003-2007) improved for patients <65 years of age (19.6%-35%; P < .001), but not for patients ≥75 years of age (7.8%-9.3%; P = .3). Among patients 65 to 74 years of age, 10-year RSRs improved for NHWs (11.3% vs 20.5%; P < .001) and Hispanics (10.6% vs 20.2%; P = .02), but not for NHBs (12.6% vs 19.5%; P = .06.). These findings confirm consistent improvement in survival for MM patients and point to the challenge of further extending these improvements to older and minority patients.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Improvements in multiple myeloma (MM) survival for patients diagnosed in the early to mid-2000s, when compared with survival of patients diagnosed in prior decades, have been well characterized.1-3 Such improvements were believed to result from higher use of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) and the introduction of novel agents, specifically the first generation of proteasome inhibitors (PIs)4,5 and immunomodulatory agents (IMiDs).6-8 However, improvements in survival were not uniform across all MM patients with no notable improvements observed among racial and ethnic minorities2,3,9 and patients diagnosed at an older age of onset.1

The clinical management of MM continues to evolve. The use of auto-HCT is expanding,10 PIs5,11 and IMiDs7,11-13 have become part of initial and maintenance therapy, and several new agents have been incorporated into the management of relapsed disease, each with anticipated improvements in survival. We hypothesize that survival for MM patients will continue to improve and increases in survivorship may now be evident among racial and ethnic minorities and older patients.

Methods

We used the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry (SEER-13) to calculate the incidence and relative survival rates (RSRs) of MM in the United States for 4 time periods consistent with notable changes in MM treatment, including 1993 to 1997 (prethalidomide), 1998 to 2002 (introduction of thalidomide),6,8 2003 to 2007 (introduction of bortezomib and lenalidomide),4 and 2008 to 2012 (upfront use of PI and IMiDs, early availability of carfilzomib and pomalidomide).5,7,11,14,15 The 13 registries that constitute SEER-13 include 13.4% of the US population. Follow-up data were available through the end of 2013 (November 2015 submission).

MM was defined based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (third revision, codes 9732/3 and 9733/3). Demographic data including year of diagnosis, sex, race, and ethnicity were available for each case. Patients were categorized into 3 race/ethnicity groups (non-Hispanic whites [NHWs], non-Hispanic blacks [NHBs], and Hispanics) and separately into 3 age groups consistent with the median age of diagnosis of 69 years and with maximizing the distribution of cases across all age categories (<65, 65-74, ≥75 years at diagnosis). In addition, MM patients aged <65 years often receive auto-HCT; however, transplantation is less frequently performed for patients aged 65 to 74 years and rarely for patients 75 years or older.10 SEER-13 registry data do not include systemic treatment information or distinguish between symptomatic and smoldering MM.

We calculated age-adjusted incidence rates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals using SEER*Stat 8.3.2. The RSR is defined as the ratio of the observed and expected survival in the general US population of similar age, race, and sex. The use of RSR, as opposed to overall survival, minimizes the effect of competing causes of death and is a better indicator of the effect of the disease on survival. Contrary to disease-specific survival, RSR is not influenced by cause of death. We compared continuous variables by group using the Kruskal-Wallis test for nonparametric data and rates using the Z test. A 2-sided P value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

We included a total of 34 505 MM patients, of whom n = 7494 were diagnosed between 1993 and 1997, n = 7952 were diagnosed between 1998 and 2002, n = 8803 were diagnosed between 2003 and 2007, and n = 10 256 were diagnosed between 2008 and 2012. Overall, 13 229 patients (38.3%) were aged <65 years, 9834 patients (28.5%) aged 65 to 74 years, and 11 442 patients (33.2%) aged 75 years or older. There were 21 660 NHW patients (62.8%), 6349 NHB patients (18.4%), and 3599 Hispanic patients (10.4%). The remaining 2897 patients (8.4%) belonged to one of multiple other racial minorities.

Incidence

Overall, MM incidence (MM cases per 100 000 persons) increased from 5.52 in 1993 to 1997 to 6.08 in 2008 to 2012 (P < .001). An increase in the incidence rate was significant among NHW women (4.15-4.36; P = .05), NHW men (6.39-7.22; P < .001), and NHB men (13.94-16.15; P < .01), but not among NHB women (10.96-11.57; P = not significant [n.s.]), Hispanic men (6.46-6.45; P = n.s.), or Hispanic women (4.24-4.39; P = n.s.) (supplemental Figure 1). The median age at diagnosis decreased from 73 to 71 years among NHW women (P < .001), whereas no notable difference in age at diagnosis was observed for NHW men (71-70 years; P = n.s.), NHB women (68-66 years; P = n.s.), NHB men (67-66 years; P = n.s.), Hispanic women (67-67 years; P = n.s.), or Hispanic men (66-65 years; P = n.s.).

Survival

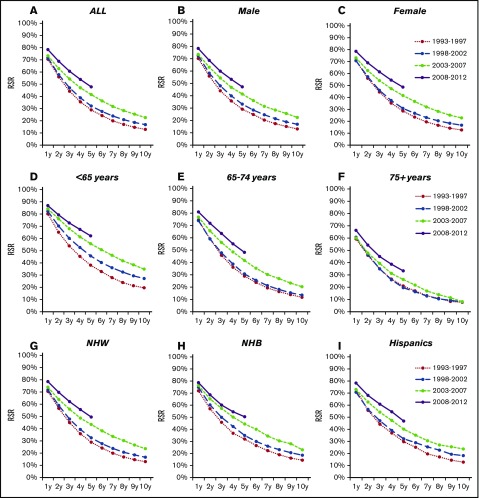

Improvement in the RSR at 5 years (RSR-5) was seen among patients <65 years of age (38.2%-61.8%; P < .001), 65 to 74 years of age (29.0%-48.4%; P < .001), and ≥75 years of age (21.1%-34.0%; P < .001). The RSR-5 improved among NHWs (29.1%-50.0%; P < .001) at a magnitude similar to that observed for NHBs (32.0%-50.1%; P < .001) and Hispanics (29.9%-47.3%; P < .001). The RSR at 10 years (RSR-10), compared between 1993 and 1997 and 2003 and 2007 (most recent cohort with available 10-year follow-up data) showed improvement among patients diagnosed at <65 years of age (19.6%-35%; P < .001) and 65 to 74 years of age (11.7%-20.6%; P < .001), but not among patients 75+ years of age (7.8%-9.3%; P = n.s.). The RSR-10 improved among NHWs (13.2%-24.3%; P < .001), NHBs (14.6%-23.4%; P < .001), and Hispanics (13.0%-23.8%; P = .001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in RSRs of patients diagnosed with MM in the United States grouped by sex, age, or race/ethnicity. Changes in RSR for all individuals (A), males (B), females (C), individuals diagnosed at age <65 years (D), individuals diagnosed at age 65 to 74 years (E), individuals diagnosed at age ≥75 years (F), NHW (G), NHB (H), and Hispanics (I) irrespective of age.

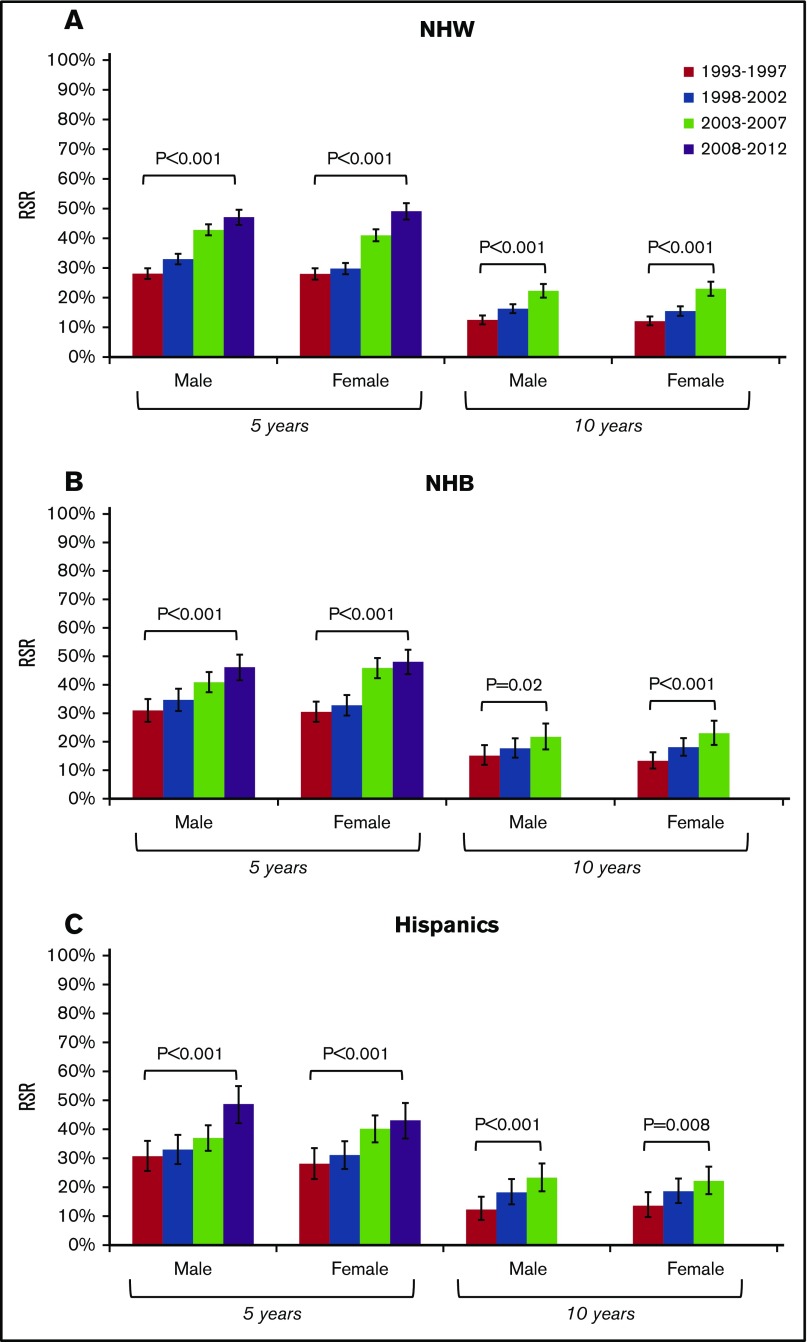

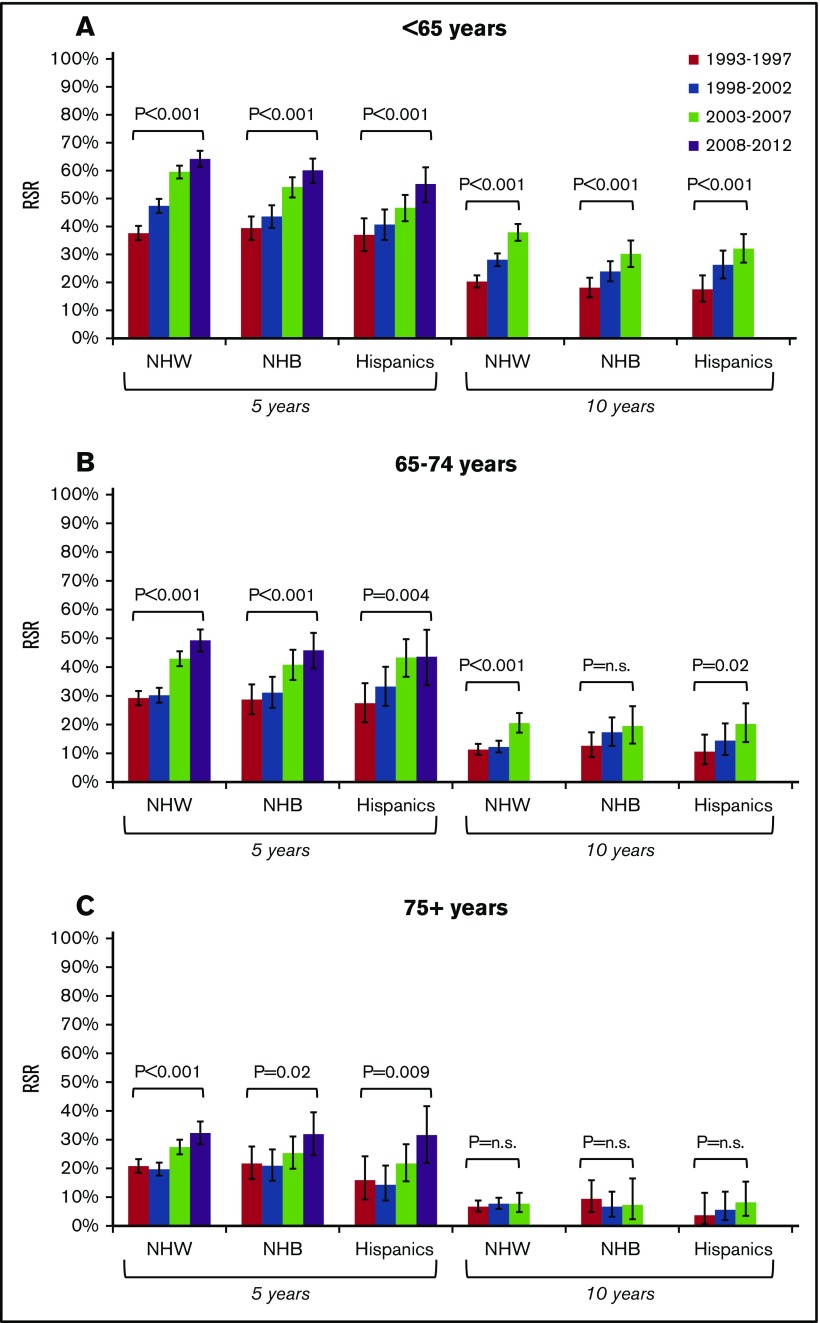

Improvements in survival by sex and race/ethnicity strata indicate gains in RSR-5 and RSR-10 for both sexes and all race/ethnicity groups (Figure 2). An analysis of survival gain by age and race/ethnicity strata indicate notable gains in the RSR-5 and RSR-10 for MM patients <65 years of age for all race/ethnicity groups. For patients aged 65 to 74 years, gains in the RSR-10 were significant for NHWs and Hispanics, but not for NHBs. Among patients aged 75+ years, gains in RSR-5 were seen for all race/ethnicity groups whereas improvements in RSR-10 were not observed for any stratum (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Changes in 5-year and 10-year relative survival of patients diagnosed with MM according to sex and race/ethnicity. Changes in 5-year and 10-year RSR for NHW (A), NHB (B), and Hispanics (C) according to sex.

Figure 3.

Changes in 5-year and 10-year relative survival of patients diagnosed with MM according to age and race/ethnicity. Changes in 5-year and 10-year RSR for patients diagnosed at age <65 years (A), 65 to 74 years (B), and ≥75 years (C) according to race/ethnicity.

Discussion

Our analysis is the first to suggest notable gains in 5-year survival among racial/ethnic minorities and to identify a gain in 10-year survival among MM patients aged 65 to 74 years, which is limited to NHW and Hispanic patients. We also confirm that improvements in 5-year survival were observed among older MM patients. Most prior reports of population-based survival in MM patients used SEER-91,2 and included follow-up data ending prior to 2010.1-3,9 Because we now have prolonged follow-up for the 4 additional registries added in 1992 (resulting in SEER-13), the present study includes a longer follow-up time than prior studies and consequently includes a larger and more diverse population.

The reasons for still no substantial improvement in RSR-5 among NHBs aged 65 to 74 years and among individuals 75+ years of age irrespective of race/ethnicity are not completely understood. It is possible that access to care and cultural patterns of interaction with health care play a bigger role than any biological aspect. Much of the improvement in MM survival is credited to broader use of auto-HCT. We have recently shown that even though utilization of auto-HCT continues to increase, it is still very low among patients 65 years of age or older,10 despite abundant evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of auto-HCT among older individuals.16 Patients of ethnic minorities are also nearly 50% less likely to access auto-HCT than NHWs.17

In addition to broader use of auto-HCT, improvements in MM survival have been linked to development of novel conventional agents in the upfront and relapsed setting. It is therefore concerning that older and minority individuals are substantially underrepresented among MM clinical trial participants.18 It is also quite possible that observations made on outcomes of minority patients with MM are indeed a reflection of socioeconomic status, rather than race/ethnicity itself. In fact, we have recently shown that marital status, insurance status, and income are linked to survival of MM; minority patients are more likely to be not married, under or uninsured, and live in low-income neighborhoods.19

The finding of increased incidence of MM and younger age at diagnosis in select populations is intriguing. It is possible that these findings reflect greater utilization of health care services allowing for earlier identification of cases. Early diagnosis may be implicated in longer survival at the population level either by triggering early life-extending therapeutic interventions or by increasing the proportion of asymptomatic smoldering MM (SMM) cases. In fact, a recent analysis based on the National Cancer Database (NCDB) found that ∼1 in 7 MM cases in the United States can be defined as SMM and noted increase in survival of SMM patients between 2003 and 2007 and 2008 and 2011.20 Unfortunately, SEER does not distinguish between smoldering and active cases of MM, preventing us from further detailing the analysis.

Although our findings indicate continuous improvement in survival of MM patients, they also point to the challenge of improving long-term outcomes particularly among older and minority patients. Furthermore, it highlights the need to increase access of older and minority patients to auto-HCT and novel and experimental therapies, including therapies tailored to more frail individuals.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: L.J.C. and E.E.B. designed the study; L.J.C. and I.K.B. collected data; L.J.C. wrote the first version of the manuscript; and L.J.C., J.O., I.K.B., K.G., S.K.K., and E.E.B. analyzed the data, edited the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luciano J. Costa, University of Alabama at Birmingham, North Pavilion–NP 2554, 1802 6th Ave South, Birmingham, AL 35294; e-mail: ljcosta@uabmc.edu.

References

- 1.Kristinsson SY, Anderson WF, Landgren O. Improved long-term survival in multiple myeloma up to the age of 80 years. Leukemia. 2014;28(6):1346-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waxman AJ, Mink PJ, Devesa SS, et al. . Racial disparities in incidence and outcome in multiple myeloma: a population-based study. Blood. 2010;116(25):5501-5506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, et al. . Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: a SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(1):91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, et al. ; Assessment of Proteasome Inhibition for Extending Remissions (APEX) Investigators. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2487-2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. ; VISTA Trial Investigators. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):906-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. . Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1565-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, et al. ; MM-015 Investigators. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1759-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. ; Multiple Myeloma (010) Study Investigators. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2123-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jansen L, Jeffreys M. Recent improvement in survival of patients with multiple myeloma: variation by ethnicity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1083-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LJ, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. . Trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous transplantation as early therapy for multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(11):1615-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. ; GIMEMA Italian Myeloma Network. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010;376(9758):2075-2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. . Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1770-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. . Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(10):895-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagannath S, Vij R, Stewart K, et al. ; Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium (MMRC). Final results of PX-171-003-A0, part 1 of an open-label, single-arm, phase II study of carfilzomib (CFZ) in patients (pts) with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl 15):8504. [Google Scholar]

- 15.San Miguel J, Weisel K, Moreau P, et al. . Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone versus high-dose dexamethasone alone for patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (MM-003): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(11):1055-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma M, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. . Older patients with myeloma derive similar benefit from autologous transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20(11):1796-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa LJ, Huang JX, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(4):701-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa LJ, Hari PN, Kumar SK. Differences between unselected patients and participants in multiple myeloma clinical trials in US: a threat to external validity. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(12):2827-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa LJ, Brill IK, Brown EE. Impact of marital status, insurance status, income, and race/ethnicity on the survival of younger patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3183-3190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravindran A, Bartley AC, Holton SJ, et al. . Prevalence, incidence and survival of smoldering multiple myeloma in the United States. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(10):e486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.