Key Points

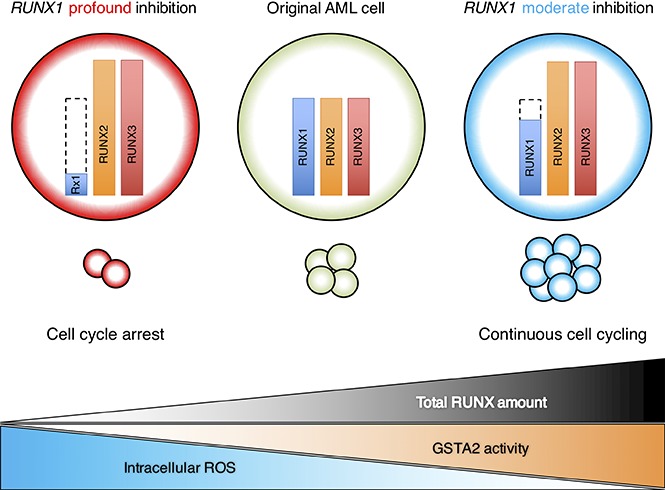

Moderate attenuation of RUNX1 expression upregulates total RUNX expressions and enhances leukemogenesis through RUNX-GSTA2-ROS axis.

Inhibiting GSTA2 function in vivo prolongs the overall survival of AML mice with intermediate RUNX1 expressions.

Abstract

Besides being a classical tumor suppressor, runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) is now widely recognized for its oncogenic role in the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Here we report that this bidirectional function of RUNX1 possibly arises from the total level of RUNX family expressions. Indeed, analysis of clinical data revealed that intermediate-level gene expression of RUNX1 marked the poorest-prognostic cohort in relation to AML patients with high- or low-level RUNX1 expressions. Through a series of RUNX1 knockdown experiments with various RUNX1 attenuation potentials, we found that moderate attenuation of RUNX1 contributed to the enhanced propagation of AML cells through accelerated cell-cycle progression, whereas profound RUNX1 depletion led to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis. In these RUNX1-silenced tumors, amounts of compensative upregulation of RUNX2 and RUNX3 expressions were roughly equivalent and created an absolute elevation of total RUNX (RUNX1 + RUNX2 + RUNX3) expression levels in RUNX1 moderately attenuated AML cells. This elevation resulted in enhanced transactivation of glutathione S-transferase α 2 (GSTA2) expression, a vital enzyme handling the catabolization of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as advancing the cell-cycle progressions, and thus ultimately led to the acquisition of proliferative advantage in RUNX1 moderately attenuated AML cells. Besides, treatment with ethacrynic acid, which is known for its GSTA inhibiting property, actually prolonged the survival of AML mice in vivo. Collectively, our findings indicate that moderately attenuated RUNX1 expressions paradoxically enhance leukemogenesis in AML cells through intracellular environmental change via GSTA2, which could be a novel therapeutic target in antileukemia strategy.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

RUNX1, a member of RUNX transcription family proteins (RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3), is an essential transcription factor mediating diverse functions in mammalian cells including cell differentiation, proliferation, cell-cycle regulation, and apoptosis. RUNX1 forms a stable heterodimeric complex with core-binding factor beta on the genome DNA sequence specifically and enhances the transcription of the target genes. Frequent gene alterations including mutations and translocations in RUNX1 provided the basis for classical conception that regards RUNX1 as an oncosuppressor.1,2 This classical viewpoint has been challenged by our recent findings that wild-type RUNX1 is stringently required for the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with inv(16) or with mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) fusions.3-5 We have also discovered the requirement of RUNX family proteins in the maintenance of leukemia cells as well as of tumors derived from various origins and first shed light on the oncogenic property of RUNX family proteins in the initiation and maintenance of malignant tumors in general.6 Although we have revealed the functional redundancy of RUNX family members in leukemogenesis and the significance of total amount of RUNX family (RUNX1 + RUNX2 + RUNX3) expressions in the maintenance of AML cells in the previous report, the impact of RUNX1 expression levels on the total amount of RUNX expressions or the precise mechanism of RUNX1-derived tumorigenesis remains elusive.6

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) is a cytosolic and membrane-bound enzyme handling the detoxification of electrophilic compounds such as chemotherapeutic drugs, environmental toxins, and products of oxidative stress, through conjugating with glutathione. At present, 8 distinct classes of the soluble cytoplasmic mammalian glutathione S-transferases have been identified, and the α subtype (GSTA) is the most abundant form among them.7 In addition to metabolizing bilirubin and certain anticancer drugs in the liver, GSTA is reported to exhibit glutathione peroxidase activity, thereby protecting the cells from ROS and the products of peroxidation. The accumulating intracellular ROS leads to transient cell-cycle arrest and protects genome DNAs from unnecessary oxidative injury from ROS.8 GSTA is therefore considered to function as a pro-oncogenic enzyme through down-regulating intracellular ROS levels and advancing cell- cycle progressions.9,10 Despite these findings, little has been known about the interaction between RUNX family genes and GST or ROS.

We herein address the impact of the varying levels of RUNX1 expressions on the total amount of RUNX expressions and on the propagation of AML cells as well as on the clinical outcomes and investigate the novel leukemogenic RUNX-GST-ROS axis.

Methods

Cell lines

AML-derived MV4-11 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. AML-derived OCI-AML2, OCI-AML3, and MOLM-13 cells were purchased from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Germany). These AML cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS). HEK293T cells were purchased from RIKEN BioResource Center (BRC; Japan) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium with 10% FBS and 1% PS. Cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Cell proliferation

To assess cell proliferation, we seeded 1 × 105 cells of the indicated AML-derived cells in a 6-well plate. For the tetracycline inducible gene or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expressions, doxycycline was added to the culture at a final concentration of 3 μM. Trypan blue dye exclusion assays were performed every other day.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed with Reverse Script Kit (TOYOBO) to generate complementary DNA (cDNA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was carried out with 7500 Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Primers used for qRT-PCR were listed in supplemental Table 1.

ChIP-qPCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP) was performed by using SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. After glycine quenching, cell pellets were collected, lysed, and then subjected to sonication with Q55 sonicator system (QSONICA). The supernatant was diluted with the same sonication buffer and processed for immunoprecipitation with the following antibodies at 4°C overnight: anti-RUNX1 antibody (ab23980; Abcam), anti-RUNX2 antibody (D1L7F; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-RUNX3 antibody (ab11905; Abcam). The beads were then washed and DNA was reverse cross-linked and purified. Following ChIP, DNA was quantified by qPCR using the standard procedures for 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Primers used for ChIP-qPCR are listed in supplemental Table 2.

siRNA interference

Specific shRNAs targeting human RUNX1 and GSTA2 were designed and subcloned into pENTR4-H1tetOx1, CS-RfA-ETV, and CS-RfA-ETR vectors (RIKEN BRC). Nontargeting control shRNA was designed against luciferase (sh_Luc.). The target sequences are provided in supplemental Table 3.

Expression plasmids

We have amplified cDNAs for human RUNX1, RUNX2, RUNX3, and GSTA2 and then inserted them into CSII-EF-MCS-IRES2-Venus, CSII-EF-MCS-IRES2-hKO1, and CSIV-TRE-Ubc-KT expression vectors. All of the PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing.

Production and transduction of lentivirus

For the production of lentivirus, HEK293T cells were transiently cotransfected with lentivirus vectors such as psPAX2 and pMD2.G by polyethylenimine (PEI, Sigma-Aldrich). Forty-eight hours after transfection, viral supernatants were collected and immediately used for infection, and then successfully transduced cells were sorted by flow cytometer Aria III (BD Biosciences).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was conducted as has been previously described.11 Briefly, cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM Na3VO4, 1× protease inhibitor [Roche], and PhosSTOP [Roche]). Whole-cell extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti-RUNX1 (A-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-GAPDH (FL-335, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-RUNX2 (D1L7F, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-RUNX3 (D6E2, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-GSTA2 (NBP1-32157, Novus Biologicals, LLC) antibodies. For secondary antibodies, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) were used. Blots were visualized using Chemi-Lumi One Super (nacalai tesque, Inc.) and ChemiDoc XRS+ Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.), according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Protein levels were quantified with Image Laboratory Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections using antibodies directed against human CD45 antigen (IR751, DAKO) for xenograft experiments. The antigen–antibody complexes were visualized with Histofine Simple Stain MAX PO (Nichirei Bioscience). The tissue section images were captured using a BZ-X700 All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence, Japan).

Luciferase reporter assay

Putative promoter region of GSTA2 (−1590 bp to +100 bp of transcription start site) was cloned from the genomic DNA of MV4-11 cells using the following primers: F 5′-CATAGTAAAATGCCTATGACCAGATT-3′ and R 5′-ATGCTGTCACCTTTGTGGC-3′; it was then subcloned into pGL4.20 (luc2/Puro) vector (Promega). Both pGL4.20 GSTA2 promoter vector and pRL-CMV control vector (TOYO B-Net Co., LTD.) were cotransfected into HEK293T cells that are stably expressing shRNAs of sh_RUNX1_moderate, sh_RUNX1_profound, and sh_Luc., or expression vectors of RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3. Promoter activities were measured using PicaGene Dual Sea Pansy Luminescence Kit (TOYO B-Net Co., Ltd.) and detected by ARVO X5 (Perkin Elmer), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ROS detection assay

Intracellular ROS accumulation was measured by using ROS-Glo H2O2 Assay Kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ARVO X5 (Perkin Elmer) was used to read the luminescence.

Cell cycle and apoptosis assay

For cell-cycle analysis, cells were fixed in fixation buffer and permeabilized with permeabilization wash buffer (BioLegend), followed by an incubation with PBS containing 3% heat-inactivated FBS, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and 100 μg/mL of RNase A. Cells were then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. For apoptosis assay, apoptotic cells were detected by Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit APC (eBioscience Inc.). In brief, approximately 2 × 105 cells of the indicated control and experimental groups were washed in PBS, suspended in annexin-binding buffer, and then mixed with 5 μL of annexin V. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min. After incubation, cells were diluted, stained with DAPI, and processed for flow cytometric analysis.

Analysis of gene expression microarray

MV4-11 cells were transduced with control shRNA (sh_Luc.) or with shRNAs targeting RUNX1 and subsequently incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline. Twenty-four hours after incubation, total RNA was prepared, and its quality was assessed by using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Cyanine 3-labeled cRNA was generated in the presence of T7 polymerase and purified, and its concentration was measured by using Nanodrop ND1000 (version 3.5.2; Thermo Scientific). The resultant cRNA (825 ng) was fragmented and subsequently hybridized with Human Gene 2.1 ST Array Strip (Affymetrix). The raw data together with the associated sample information were analyzed by GeneSpring GX (version 12.1.0; Agilent Technologies), and our microarray data have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO Series accession no. GSE98748). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was used to analyze the microarray data obtained in the present study.12

Statistics

Statistical significance of differences between control and experimental groups was assessed by a 2-tailed unpaired Student t test and was declared if the P value was less than .05. Equality of variances in 2 populations was calculated with an F test. The results were represented as the average ± standard error of the mean (SEM) values obtained from 3 independent experiments. In transplantation experiments, animals were randomly allocated to each experimental group, and the treatments were given with blinding. The overall survival of mice was shown in a Kaplan-Meier curve. Survival between the indicated groups was compared using the log-rank test.

Mice

Nonobese diabetic (NOD)/Shi severe combined immunodeficiency (scid), interleukin (IL) 2RγKO (NOG) mice were purchased from the Central Institute for Experimental Animals (Japan). Littermates were used as controls in all experiments.

Xenograft mouse model

Xenograft mouse models of human cancer cell lines were developed using NOG mice. For leukemia mouse models, 2.0 × 106 cells/body of MV4-11 cells were intravenously injected. Peripheral blood was then collected every week, and chimerism was checked by flow cytometer using anti-human CD45 antibody (BD Biosciences). Seven days after injection, mice were treated with ethacrynic acid (10 to 25 mg/kg body weight, daily per oral [po] administrations) or with the equivalent amount of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Mice were also continuously given oral doxycycline through drinking water 7 days after posttransplant (diluted in drinking water at 1 mg/mL + 3% sucrose).

Study approval

All animal studies were properly conducted in accordance with the Regulation on Animal Experimentation at Kyoto University, on the basis of International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research Involving Animals. All procedures used in this study were approved by Kyoto University Animal Experimentation Committee (permit no. Med Kyo 14332).

Results

RUNX1 moderate inhibition confers proliferative advantage to AML cells

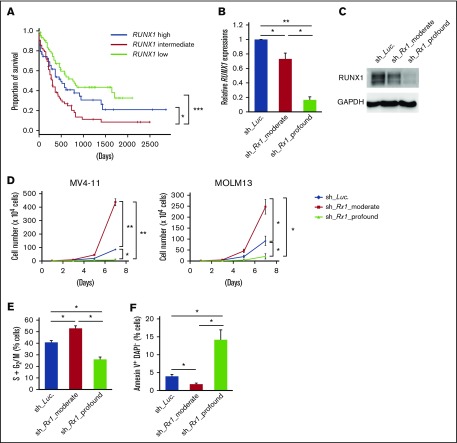

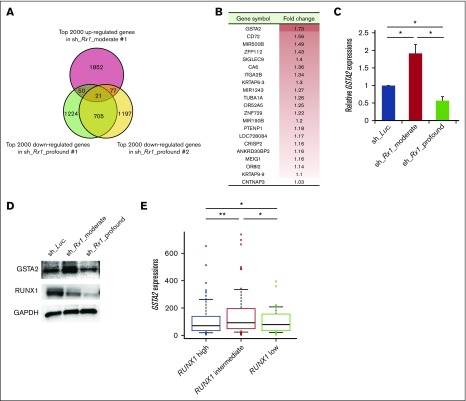

To explore whether levels of RUNX1 expression influence the prognosis of AML patients, we first examined them in de novo AML patient cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) clinical dataset (n = 187). As is shown in supplemental Figure 1, close inspection of RUNX1 expressions in these patients revealed 3 distribution peaks. Because all of them followed normal distribution pattern when divided according to their RUNX1 expressions (RUNX1 high: n = 62; RUNX1 intermediate: n = 63; RUNX1 low: n = 62) and the basic background characteristics such as age, sex, and cytogenetic risks of the patients allocated were similar among these cohorts (supplemental Table 4), we compared the overall survival periods among them to verify the significance of RUNX1 expressions in the prognosis of AML patients. Intriguingly, as shown in Figure 1A, we found that RUNX1 intermediately expressing AML patients exhibited the worst clinical outcomes (shortest overall survival periods) among these 3 cohorts. We also found that AML patients with low RUNX1 expressions showed favorable prognosis in relation to those with intermediate or high RUNX1 expressions (Figure 1A). These facts prompted us to hypothesize that moderately attenuated RUNX1 expression might accelerate the propagation of AML cells and profoundly repressed RUNX1 decelerate it. To address this issue, we prepared several tetracycline-inducible short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) that could control the expressions of RUNX1 at various levels in AML cells (MV4-11 and MOLM-13 cells). Interestingly, although AML cells that were transduced with shRNAs that could profoundly downregulate RUNX1 expressions below 10% of their original expressions at protein level (sh_Rx1_profound 1 and 2), deteriorated the proliferation speed of AML cells, AML cells that were transduced with shRNAs that could moderately downregulate RUNX1 expressions to around 70% of their original expressions (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 and 2) paradoxically doubled the growth rate of AML cells in comparison with the control AML cells transduced with shRNA-targeting luciferase gene (sh_Luc.) (Figure 1B-D). Both MV4-11 and MOLM-13 cell lines are derived from AML patients with MLL gene rearrangements, and previous reports suggest close interaction between RUNX1 and MLL.3,13 To further extend the robustness of our findings in AML, we also prepared sh_Rx1_profound-transduced or sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced AML cell lines without MLL rearrangements such as OCI-AML2 and OCI-AML3 cells. As we have expected, the results obtained in these AML cell lines were thoroughly consistent with those obtained in MV4-11 and MOLM-13 cells, underscoring the importance of finely tuned RUNX1 expressions in the proliferation of AML cells in general (supplemental Figure 2A-B). As is shown in Figure 1E-F and supplemental Figure 3A-E, AML cells transduced with sh_Rx1_profound showed cell-cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase and enhanced apoptotic cell death, whereas AML cells transduced with sh_Rx1_moderate showed advancement of cell-cycle progression and a reduced number of apoptosis cells. To investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms of this paradoxical enhancement of tumor cell proliferation in RUNX1 moderately inhibited cells, we compared and analyzed the global gene expression patterns in MV4-11 cells transduced with sh_Luc., sh_Rx1_moderate, and sh_Rx1_profound. To obtain a list of genes that are consistently upregulated in RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells while simultaneously downregulated in RUNX1 profoundly inhibited ones, we first extracted the top 2000 upregulated genes in sh_Rx1_moderate-tranduced MV4-11 cells and top 2000 downregulated genes in sh_Rx1_profound-transduced MV4-11 cells in relation to sh_Luc.-transduced control cells (Figure 2A). We then picked up 21 genes commonly upregulated in the RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells while tightly downregulated in the RUNX1 profoundly inhibited AML cells (Figure 2B). Among these genes, we focused on the top-ranked gene GSTA2, because emerging evidence suggests oncogenic property of GST family genes through intracellular ROS scavenging and cell-cycle progression advancement.7-9 Indeed, qRT-PCR and immunoblotting revealed elevation of GSTA2 expression in RUNX1 moderate-inhibition and suppression of it in RUNX1 profound-inhibition both at mRNA and protein levels (Figure 2C-D). Besides, analysis of gene expression profiles in the previously mentioned TCGA dataset elucidated that the AML cells derived from RUNX1 intermediately expressing AML patients exhibited the highest GSTA2 expressions. These facts collectively indicated the existence of an underlying mechanism involving GSTA2 that confers a growth advantage to AML cells with moderately inhibited RUNX1 expressions (Figure 2E).

Figure 1.

Moderate inhibition of RUNX1 confers proliferative advantage to AML cells. (A) Overall survival of AML patients from TCGA clinical datasets (n = 187). Patients were divided into 3 groups according to their RUNX1 expressions (RUNX1 high: n = 62; RUNX1 intermediate: n = 63; RUNX1 low: n = 62). (B) Efficacy of shRNAs targeting RUNX1. MV4-11 cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Luciferase (sh_Luc.) or shRNAs against RUNX1 (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 or sh_Rx1_profound 1) and incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h, then total RNA was prepared and analyzed by RT-PCR. Values are normalized to that of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (C) Immunoblot showing the RUNX1 expressions in panel B. (D) Growth curves of MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 or sh_Rx1_profound 1). Cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline (n = 3). (E) RUNX1 depletion-mediated change in the number of cells with S + G2/M phase DNA content. MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 or sh_Rx1_profound 1) were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (F) Frequency of early apoptotic cell death induced by RUNX1 silencing. MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 or sh_Rx1_profound 1) were treated as in panel E, and the early apoptotic cells (annexin V+ DAPI−) were scored by flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05; **P < .01, by 2-tailed Student t test (except for panel A); ***P < .001, by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

Figure 2.

Upregulation of GSTA2 in RUNX1 moderately attenuated AML cells. (A) Venn diagram showing the common genes that are upregulated in the RUNX1 moderately inhibited MV4-11 cells (sh_Rx1_moderate_1) while tightly downregulated in the RUNX1 profoundly inhibited ones (sh_Rx1_profound_1 and 2). (B) List of 21 genes extracted in panel A. Fold change of each gene was calculated by dividing the signal intensity of each gene in RUNX1 moderately inhibited MV4-11 cells by that in MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.). (C) GSTA2 expressions were determined in MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Luciferase (sh_Luc.) or shRNAs against RUNX1 (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 or sh_Rx1_profound 1). Cells were incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h, then total RNA was prepared and analyzed by RT-PCR. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (D) Immunoblot of GSTA2, RUNX1, and GAPDH in MV4-11 cells used in panel C. (E) GSTA2 expressions were analyzed in the AML patients from TCGA clinical datasets as in Figure 1A (RUNX1 high: n = 62; RUNX1 intermediate: n = 63; RUNX1 low: n = 62). Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05; **P < .01, by 2-tailed Student t test.

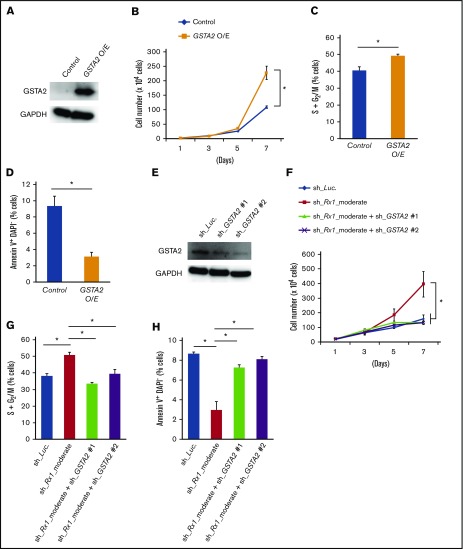

GSTA2 plays a key role in the accelerated proliferation of RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells

To further elucidate the possible involvement of GSTA2 in this paradoxically accelerated proliferation rate in RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells, we examined the effect of additive expression of GSTA2 in AML cells. As is shown in Figure 3A-D, GSTA2-overexpressed MV4-11 cells showed increased proliferation rate, enhanced advancement of cell-cycle progression, and suppressed the frequency of apoptotic cells to the extent observed in RUNX1 moderately inhibited MV4-11 cells. Moreover, additive knockdown of GSTA2 in sh_Rx1_moderate-tranduced MV4-11 cells exhibited suppression of its growth speed and cell-cycle advancement to the control levels (Figure 3E-G) as well as reverted the sh_Rx1_moderate-derived downregulation of apoptosis (Figure 3H). Moderate inhibition of RUNX1-mediated growth advantage was consistently canceled by additional GSTA2 knockdown in other AML cell lines as well (supplemental Figure 4A-C). These findings elucidated the importance of GSTA2 expressions in this paradoxically accelerated proliferation speed of RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells. We next tried to clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms of how GSTA2 confers growth advantage to AML cells.

Figure 3.

GSTA2 confers proliferation of AML cells through promoting cell cycle advancements. (A) Immunoblot of GSTA2 and GAPDH in MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus expressing GSTA2 or control. Cells were incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h before being lysed for protein extraction. (B) Growth curves of MV4-11 cells transduced with control or GSTA2-expressing vector (GSTA2 O/E). Cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline (n = 3). (C) Additive GSTA2 expression-mediated change in the number of cells with S + G2/M-phase DNA content. MV4-11 cells transduced with control or GSTA2-expressing vector (GSTA2 O/E) were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (D) Frequency of early apoptotic cell death induced by additive GSTA2 expression. MV4-11 cells transduced with control or GSTA2-expressing vector (GSTA2 O/E) were treated as in panel C, and the early apoptotic cells (annexin V+ DAPI−) were scored by flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (E) Immunoblot of GSTA2 and GAPDH in MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Luciferase (sh_Luc.) or shRNAs against GSTA2 (sh_GSTA2 1 or sh_GSTA2 2). Cells were incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h. (F) Growth curves of MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Luciferase (sh_Luc.) or shRNAs against GSTA2 (sh_GSTA2 1 or sh_GSTA2 2) with or without simultaneous transduction of shRNA targeting RUNX1 (sh_Rx1_moderate). Cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline (n = 3). (G) Additive GSTA2 knockdown-mediated change in the number of cells with S + G2/M-phase DNA content were determined in RUNX1 moderately attenuated MV4-11 cells. MV4-11 cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline as in panel F. Forty-eight hours after treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (H) Frequency of early apoptotic cell death induced by additive GSTA2 knockdown in RUNX1 moderately attenuated MV4-11 cells. MV4-11 cells were cultured and treated as in panel G, and the early apoptotic cells (annexin V+ DAPI−) were scored by flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05, by 2-tailed Student t test. O/E, overexpression.

GSTA2 overexpression confers proliferative advantage to AML cells through enhancing intracellular ROS catabolization

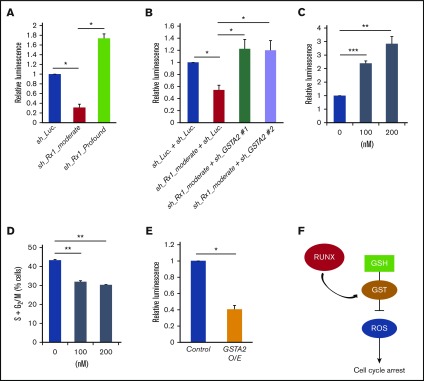

Because GSTA2 catabolizes and scavenges free radicals such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and decreased intracellular free radicals have been shown to accelerate the cell-cycle advancement,8,10 we first measured the amount of intracellular ROS in RUNX1-inhibited AML cells. As is shown in Figure 4A, intracellular ROS accumulation was decreased in sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced MV4-11 cells and increased in AML cells transduced with sh_Rx1_profound. Besides, additive delivery of sh_RNAs targeting GSTA2 to sh_Rx1_moderate-tranduced MV4-11 cells restored the intracellular ROS accumulation to the control level (Figure 4B). Indeed, direct ROS induction with β-lapachone, a validated topoisomerase I inhibitor, significantly decelerated the cell-cycle progression in these AML cells (Figure 4C-D). Furthermore, as is shown in Figures 3B and 4E, forced expression of GSTA2 to MV4-11 cells conferred proliferative advantage through suppressing the intracellular ROS content, underscoring the idea that growth advantage conferred by moderate RUNX1 inhibition could be attributed to the sequential upregulation of GSTA2 and downregulation of intracellular ROS accumulation in AML cells (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

GSTA2-mediated intracellular ROS removal positively-affects the proliferation of AML cells. (A) Intracellular ROS content was measured by a luminometer in MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate and sh_Rx1_profound) in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (B) Intracellular ROS content was measured in MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus encoding shRNA targeting Luciferase (sh_Luc.) or shRNAs against GSTA2 (sh_GSTA2 1 or sh_GSTA2 2) with or without simultaneous transduction of shRNA-targeting RUNX1 (sh_Rx1_moderate) in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 hours. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (C) Intracellular ROS content was measured in MV4-11 cells treated with β-lapachone at 100 to 200 nM or DMSO for 24 h (n = 3). (D) The number of cells with S + G2/M-phase DNA content was determined in MV4-11 cells, as in panel C. Twenty-four hours after treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (E) Intracellular ROS amount was measured in MV4-11 cells transduced with lentivirus-expressing GSTA2 or control. Cells were incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h, then harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (F) Graphic showing the interaction of RUNX, GST, ROS, and their effect on the cell cycle progression in AML cells. RUNX modulate the expression of GSTA2 in AML cells and subsequently reduce intracellular ROS accumulations, which in turn promote the cell cycle advancement and contribute to the propagation of the disease. Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05, by 2-tailed Student t test; **P < .01; ***P < .001. GSH, glutathione.

Significance of total amount of RUNX expressions in GSTA2 upregulation

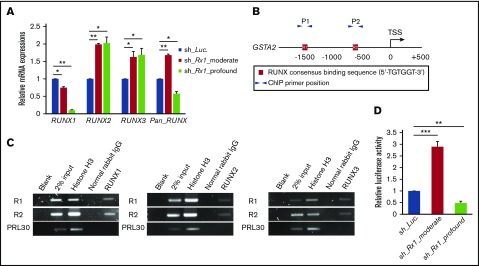

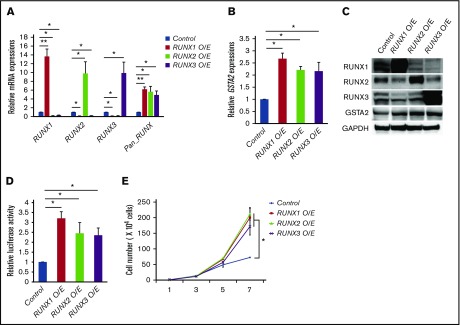

We next investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying this completely opposite directional regulation of GSTA2 expression between RUNX1 profoundly and moderately attenuated AML cells. To address this issue, we first checked the expressions of other RUNX family members such as RUNX2 and RUNX3 upon RUNX1 silencing, because RUNX family members have redundant biological functions in leukemogenesis6 and this mutual compensation among RUNX family members could possibly take part in the fine-tuning of GSTA2 expressions. Interestingly, the equivalent level of compensatory upregulation of RUNX2 and RUNX3 expressions were observed in sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced and sh_Rx1_profound-transduced AML cells. These elevations created an absolute gap in the total amount of RUNX family (RUNX1 + RUNX2 + RUNX3) expressions in between sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced and sh_Rx1_profound-transduced AML cells, which was confirmed by RT-qPCR with primers amplifying the specific sequence common to all RUNX family members (Figure 5A). ChIP assay in the proximal promoter region of the GSTA2 gene proved the direct association of RUNX family members with this genomic area (Figure 5B-C). Luciferase reporter assay using the GSTA2 promoter showed elevation of reporter signals in sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced cells and suppression of them in sh_Rx1_profound-transduced cells (Figure 5D). Consistent with these findings, forced upregulation of the total amount of RUNX expression by additive RUNX1, RUNX2, or RUNX3 expressions in AML cells (Figure 6A) resulted in transactivation of GSTA2 expression (Figure 6B-D) and augmented cell proliferations in AML cells (Figure 6E). In summary, these data indicate that each RUNX family member enhances transactivation of GSTA2 expression in AML cells; paradoxically upregulated total RUNX expressions by moderate inhibition of RUNX1 results in increased expression of GSTA2; and upregulated GSTA2 transcripts subsequently confer a growth advantage to RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells through suppressing intracellular ROS accumulation.

Figure 5.

Moderate inhibition of RUNX1 paradoxically upregulates total RUNX expression. (A) Expressions of RUNX1, RUNX2, RUNX3, and total RUNX (Pan_RUNX) were determined in MV4-11 cells transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate and sh_Rx1_profound) in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline for 24 h. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (B) Schematic illustrations show proximal promoter region (−2000 bp to +500 bp of transcriptional start site) of GSTA2. (C) ChIP analysis in MV4-11 cells using anti-RUNX1, anti-RUNX2, or anti-RUNX3 antibodies, an isotope-matched control IgG and anti-histone H3 antibody. ChIP products were amplified by PCR to determine abundance of the indicated amplicons. R1 and R2 correspond to RUNX consensus-binding sequences in the GSTA2 promoter, as is described in panel B. PRL30 was used as a negative control. (D) Luciferase reporter assay of GSTA2 promoter. HEK293T cells were transduced with the indicated lentivirus vectors as well as with luciferase reporter plasmids and then incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline. Forty-eight hours after treatment, relative luciferase activity was determined (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05, by 2-tailed Student t test; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Figure 6.

RUNX family members transactivate GSTA2 expression. (A) Expressions of RUNX1, RUNX2, RUNX3, and total RUNX (Pan_RUNX) were determined in MV4-11 cells transduced with control or with expressing vectors of RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3 in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline for 24 h. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (B) Expressions of GSTA2 were determined in MV4-11 cells as in panel A. Values are normalized to those of control vector-transduced cells (n = 3). (C) Expressions of RUNX1, RUNX2, RUNX3, GSTA2, and GAPDH were determined in MV4-11 cells transduced with control or with expressing vectors of RUNX1, RUNX2, and RUNX3 in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline for 48 h (n = 3). (D) Luciferase reporter assay of GSTA2 promoter. HEK293T cells were transduced with the indicated lentivirus vectors as well as with luciferase reporter plasmids and then incubated with 3 μM of doxycycline. Forty-eight hours after treatment, relative luciferase activity was determined (n = 3). (E) Growth curves of MV4-11 cells as in panel A. Cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μM of doxycycline (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM values. *P < .05, by 2-tailed Student t test; **P < .01.

Targeting RUNX-GST-ROS axis in vivo

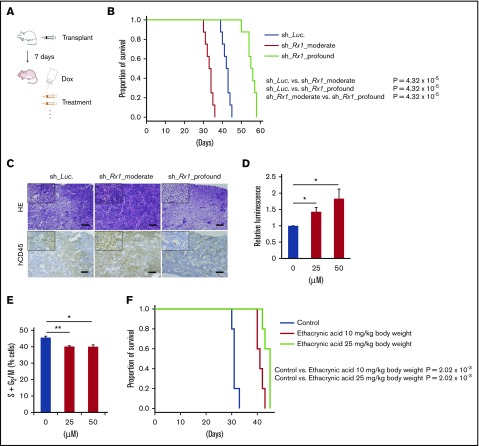

We finally examined our hypothesis in vivo using immunodeficient NOG mice xenotransplanted with human AML cells (Figure 7A). In concrete terms, we transplanted sh_Luc-, sh_Rx1_moderate-tranduced or sh_Rx1_profound-tranduced MV4-11 cells to NOG mice and induced in vivo shRNA expressions through po administration of doxycycline. As we have expected, mice transplanted with RUNX1 moderately inhibited AML cells showed shorter overall survival periods in comparison with the control mice, whereas mice transplanted with RUNX1 profoundly inhibited AML cells exhibited significant extension of overall survival periods in relation to the control mice (Figure 7B-C). To achieve effective in vivo attenuation of GSTA2 in these mice, we used ethacrynic acid in our experiments, a widely recognized potent GST inhibitor.14 Treating AML cells with ethacrynic acid in vitro indeed resulted in cell-cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase and intracellular ROS accumulations as are seen in RUNX1-profoundly inhibited AML cells (Figure 7D-E). We thus challenged NOG mice transplanted with sh_Rx1_moderate-transduced MV4-11 cells with this drug and observed their overall survival periods. As is shown in Figure 7F, AML mice treated with ethacrynic acid (10 mg/kg body weight or 25 mg/kg body weight, daily po administrations) exhibited significantly prolonged survival periods in comparison with vehicle-treated control mice. These data suggest that targeting GSTA2 could be a novel therapeutic strategy against poorest prognostic AML cases with intermediate RUNX1 expressions.

Figure 7.

Effective control of AML through targeting RUNX-GST-ROS axis in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram showing the xenotransplantation AML model in NOG mice. Mice were transplanted with 2 × 106 cells/body of MV4-11 cells stably transduced with indicated lentivirus via tail veins (day 1). At day 7, po doxycycline administration through drinking water was started. In experiments using ethacrynic acid, mice were treated either by daily po ethacrynic acid or control until they showed any physical sign of AML development. (B) Overall survival of NOG mice transplanted with MV4-11 cells properly transduced with control (sh_Luc.) or with RUNX1 shRNAs (sh_Rx1_moderate 1 and sh_Rx1_profound 1) (n = 8). P value by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (C) Representative microscopic images of bone marrow prepared from AML xenograft mice as in panel B (21 d posttransplantation). Results obtained from hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemical staining with anti-human CD45 antibody were shown (original magnification ×4 and ×20 (insets); scale bars, 100 μm). (D) Intracellular ROS content was measured in MV4-11 cells treated with ethacrynic acid at 25 to 50 μM or DMSO for 72 h (n = 3). (E) The number of cells with S + G2/M-phase DNA content was determined in MV4-11 cells as in panel D. Seventy-two hours after treatment, cells were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis (n = 3). (F) Overall survival of NOG mice transplanted with MV4-11 cells properly transduced with sh_Rx1_moderate 1. Mice were treated either by daily po ethacrynic acid (10 to 25 mg/kg body weight) or by control solvents (n = 5). P value by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Discussion

RUNX1 transcription factor plays a pivotal role in cancer development and maintenance as well as in the homeostasis of various organs.15,16 Although RUNX1 has been shown to exhibit both oncogenic and oncosuppressive properties context-dependently in various cancers, little has been known about the molecular mechanisms underlying this curious bidirectional function of RUNX1.3,5,15,17,18 In addition, although mutations in RUNX1 have been reported to demarcate poorer-prognostic cohorts in AML patients,19-21 the level of RUNX1 expression itself has not been directly linked to the outcomes of AML patients. Recently, we have reported that RUNX cluster regulation is a promising therapeutic strategy against various types of cancers, including AML.6 Although our previous work validated the antitumor potential of RUNX1-inhibiton strategy, the precise mechanisms of how RUNX1 engages in tumorigenesis remain elusive. While assessing the significance of RUNX1 expressions in the prognosis of de novo AML patients, we have coincidentally found that the RUNX1-intermediately-expressing cohort exhibit the worst outcomes among them. Therefore we focused on this “moderate” expression of RUNX1 in AML and presumed that analyzing the biology of RUNX1 moderately expressing AML cells might unveil the hidden mechanisms of RUNX-mediated tumorigenesis. Of note, the property of transcription factors acting in some contexts as activators but in others as repressors has been reported.22-27 Among them, F. Rosenbauer et al have produced interesting data showing that reducing ETS family transcription factor Pu.1 expression to 20% of wild-type levels results in an aggressive form of AML development in mice, whereas complete loss of its expression did not.24 Their finding in the balanced expression of Pu.1 in leukemogenesis is similar in nature to our findings in RUNX1 and strongly suggest the importance of finely tuned expressions of vital transcription factors in leukemogenesis.

In this report, we further addressed the underlying mechanism in this paradoxical enhancement of leukemogenesis in RUNX1 moderately attenuated AML cells and attained pieces of evidence showing that moderate inhibition of RUNX1 results in the elevation of total RUNX family expressions, which transactivates GSTA2 expression and removes intracellular ROS from AML cells. If intracellular ROS accumulation is controlled at low range, an increase in ROS is actually associated with abnormal cancer cell growth.8,10 If the increase of ROS reaches a certain threshold level that is incompatible with cellular survival, however, intracellular ROSs exert a cytotoxic effect, leading to arrest of the cell-cycle progression and induction on apoptosis in malignant cells, and limits cancer progression.8,10,28 Thus, intracellular ROS inducers constitute one of the most intensively studied antitumor strategies, and some of these drugs are clinically available with promising outcomes.28 In respect to the role of RUNX1 in ROS regulation, V. Giambra et al reported that the NOTCH1–RUNX3–RUNX1–PKC-θ transcriptional circuit plays a pivotal role in the regulation of intracellular ROS and maintenance of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cells, but to our limited knowledge, none have previously investigated the role of RUNX1 in the regulation of ROS in the context of AML cells. Taking the considerable difference in the pathogenesis of AML and ALL into account, our findings of the RUNX-GST-ROS axis are highly meaningful in the precise understanding of the role of RUNX1 in intracellular ROS control in AML cells.

To attenuate the function of GSTA2 in our study, we adopted the classical GST inhibitor ethacrynic acid, because this drug is clinically available as a diuretic drug with few side effects. In our AML mice model, we discovered a favorable impact of this drug on the prognosis of AML mice through modulating RUNX-GST-ROS axis in vivo. Our promising results and the efficacy of this implementable antileukemia strategy should be examined further in upcoming clinical trials. Taken together, these findings indicate that moderately attenuated RUNX1 expressions paradoxically enhance leukemogenesis in AML cells through intracellular environmental change via GSTA2, which could be a novel therapeutic target in antileukemia strategy.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank H. Miyoshi (RIKEN BioResource Center, Japan) for kindly providing lentivirus vectors encoding CSII-EF-MCS-IRES2-Venus, CSII-EF-MCS-IRES2-hKO1, and CSIV-TRE-Ubc-KT.

Authorship

Contribution: K.M. designed research, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; S.M. performed experiments and analyzed data; K.S., H.K., and J.T. helped to collect data; P.P.L., H.S., and S.A. commented on research direction; and Y.K. initiated the study, supervised research, and gave the final approval for submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yasuhiko Kamikubo, Human Health Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, 53 Kawahara-cho, Syogoin, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan; e-mail: kamikubo.yasuhiko.7u@kyoto-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Miyoshi H, Shimizu K, Kozu T, Maseki N, Kaneko Y, Ohki M. t(8;21) breakpoints on chromosome 21 in acute myeloid leukemia are clustered within a limited region of a single gene, AML1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(23):10431-10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu P, Tarlé SA, Hajra A, et al. . Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science. 1993;261(5124):1041-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyama S, Schibler J, Cunningham L, et al. . Transcription factor RUNX1 promotes survival of acute myeloid leukemia cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3876-3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamikubo Y, Zhao L, Wunderlich M, et al. . Accelerated leukemogenesis by truncated CBF beta-SMMHC defective in high-affinity binding with RUNX1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(5):455-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyde RK, Zhao L, Alemu L, Liu PP. Runx1 is required for hematopoietic defects and leukemogenesis in Cbfb-MYH11 knock-in mice. Leukemia. 2015;29(8):1771-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morita K, Suzuki K, Maeda S, et al. . Genetic regulation of the RUNX transcription factor family has antitumor effects. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(7):2815-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM, Dowd CA. Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily. Biochem J. 2001;360(Pt 1):1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonstra J, Post JA. Molecular events associated with reactive oxygen species and cell cycle progression in mammalian cells. Gene. 2004;337:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend DM, Tew KD. The role of glutathione-S-transferase in anti-cancer drug resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7369-7375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liou GY, Storz P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic Res. 2010;44(5):479-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita K, Masamoto Y, Kataoka K, et al. . BAALC potentiates oncogenic ERK pathway through interactions with MEKK1 and KLF4. Leukemia. 2015;29(11):2248-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. . Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545-15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson AC, Ballabio E, Geng H, et al. . RUNX1 is a key target in t(4;11) leukemias that contributes to gene activation through an AF4-MLL complex interaction. Cell Reports. 2013;3(1):116-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ploemen JH, van Ommen B, Bogaards JJ, van Bladeren PJ. Ethacrynic acid and its glutathione conjugate as inhibitors of glutathione S-transferases. Xenobiotica. 1993;23(8):913-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito Y, Bae SC, Chuang LS. The RUNX family: developmental regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(2):81-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levanon D, Groner Y. Structure and regulated expression of mammalian RUNX genes. Oncogene. 2004;23(24):4211-4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Ami O, Friedman D, Leshkowitz D, et al. . Addiction of t(8;21) and inv(16) acute myeloid leukemia to native RUNX1. Cell Reports. 2013;4(6):1131-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antony-Debré I, Manchev VT, Balayn N, et al. . Level of RUNX1 activity is critical for leukemic predisposition but not for thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2015;125(6):930-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaidzik VI, Teleanu V, Papaemmanuil E, et al. . RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia are associated with distinct clinico-pathologic and genetic features. Leukemia. 2016;30(11):2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnittger S, Dicker F, Kern W, et al. . RUNX1 mutations are frequent in de novo AML with noncomplex karyotype and confer an unfavorable prognosis. Blood. 2011;117(8):2348-2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang JL, Hou HA, Chen CY, et al. . AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood. 2009;114(26):5352-5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson DG. The paradox of E2F1: oncogene and tumor suppressor gene. Mol Carcinog. 2000;27(3):151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland BD, Peeper DS. KLF4, p21 and context-dependent opposing forces in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(1):11-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbauer F, Wagner K, Kutok JL, et al. . Acute myeloid leukemia induced by graded reduction of a lineage-specific transcription factor, PU.1. Nat Genet. 2004;36(6):624-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whittle MC, Hingorani SR. RUNX3 defines disease behavior in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;3(2):e1076588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sykes SM, Lane SW, Bullinger L, et al. . AKT/FOXO signaling enforces reversible differentiation blockade in myeloid leukemias. Cell. 2011;146(5):697-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naka K, Hoshii T, Muraguchi T, et al. . TGF-beta-FOXO signalling maintains leukaemia-initiating cells in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2010;463(7281):676-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(7):579-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.