Abstract

Background

From time immemorial, wild plants have been used for edible purposes. They still continue to be a major source of nutrition for tribal people. However, unfortunately, their use is now declining. This has implications in food security, narrowing genetic base, and future leads. The present study was, therefore, carried out in Chhota Bhangal region of Western Himalaya to analyze uses of wild edible plants (WEP) and the motivations behind their use or abandonment.

Methods

Field surveys were conducted to the study area from January 2016 to March 2017. Household surveys, group discussions, free listing, and structured questionnaires were used to elicit information on WEP. WEP use was categorized into six categories (vegetables, fruits, chutney, flavoring food, raw food, and local brew). Trends of use (continuing, decreasing, increasing, and not used) and motivations (environmental, economic, sociocultural, agriculture and land use practices, and human-wildlife conflict) behind their use were analyzed.

Results

Fifty plant species were used by the local people for edible purposes under six WEP categories. Mean and median of WEP used per respondent was 22.3 and 21, respectively. Highest number of these were used as vegetable (mean 8.9) while lowest were used as brew (mean 0.4). Out of the 50 WEP used, 20 were prioritized for motivation analyses. Though plant use is still maintained in the area, changes are evident. Almost 50% of the respondents revealed that they still continue the use of WEP while 36% reported trends of declining use as compared to 5–10 years back. Close to 10% respondents have stopped consuming WEP now and ~ 3% reported an increase in the use of WEP. Among the WEP categories, use of chutney showed an increasing trend. Sociocultural motivations were found to play a prime role, both, in limiting and promoting WEP use. Taste and aroma were the major sociocultural reasons behind using WEP while modernization and changing lifestyle were the main reasons behind declining use of WEP.

Conclusions

The study concludes that though use of WEP is still maintained in the area, changes in consumption trends are evident. Sociocultural motivations guided use of WEP in the area.

Keywords: Edible, Himalaya, Modernization, Plants, Sociocultural

Background

Wild edible plants (WEP) represent species that are collected from the surrounding ecosystems for human consumption but are not cultivated [1]. Surrounding ecosystems include forests, pastures, and fields. FAO defines them as “plants that grow spontaneously in self maintaining populations in natural or semi-natural ecosystems and can exist independently of direct human actions” [2]. Thus, WEP are locally available, low input options for nutrition. Prior to coming up of agriculture, some 10,000 years ago, they formed a prime component of human food [3]. Throughout history, WEP have enabled humans to tide over times of wars and natural calamities [4, 5]. Thus, uses of WEP have been widely studied, both, in developed and developing countries [6–8]. It has been revealed that the number and frequency of species used varies with culture and location [9–11]. At the individual country level, 300–800 different species have been reported to be used for edible purposes [12, 13]. Another study reports that humans have used more than 7000 WEP during some stage in their history [14]. Still today, WEP complement diet of 1 million people of the world [15] and continue to be a major source of food for tribal and rural communities [16, 17]. Their importance in poverty reduction, ensuring food security, agricultural diversification, income generation, and nutrition has been specially emphasized [18–20]. It is now being argued that WEP are a rich source of vitamins and nutrients [5, 21–24] and can significantly contribute towards alleviating malnutrition [15].

On the one hand, importance of WEP is being recognized globally, on the other, a decline in their consumption as well as the knowledge associated with them is evident [25–27]. Developmental activities, socio-cultural transformations, environmental changes, lack of interest among young generation, and declining resources are cited to be the major reasons for this [21, 28–31]. Therefore, studies on WEP consumption are contemporary areas of research [32]. Such studies, especially in interior areas where dependency on natural resources is still very high and at the same time they are undergoing rapid transformations, have been emphasized [33–36].

Recognizing this, the present study was carried out in Chhota Bhangal—an interior tribal area in the Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh. The objectives framed for the study include 1: documentation of WEP consumed in the area, and 2: identification of motivations and trends associated with their consumption.

Methods

Study area

The study area lies in the lap of Dhauladhar Mountain range at co-ordinates 32°04′32.83″ N and 76°51′30.45″ E in the West Himalayan state of Himachal Pradesh. Owing to its location, Chhota Bhangal receives heavy rainfall from July to September with annual rainfall close to 1500 mm. Winters are chilly, with January being the coldest month and often reporting sub-zero temperatures. Summers are usually pleasant with maximum temperature going up to 34 °C in the month of June [37]. Geologically, quartzite rocks of Saluni formation characterize the area while the soils are fertile loam to clayey loam. Uhl and Lambadug rivulets drain the area [38]. Oaks and conifer dominate the forests with birch and rhododendron forming the tree line. The area is rich in medicinal plants that are heavily traded from the region [39].

The residents of the area (referred as Bhangalis) are mainly agropastoralists and depend on the surrounding resources for livelihood including plants for edible purposes. Their knowledge on plants is exhibited in their local sayings and uses [40]. Natural landscape, trout farms, and adventure tourism such as paragliding are transforming the place into an important tourist destination. The 2015 world paragliding championship took place in the vicinity of the study area (http://www.pwca.org/node/24227). Therefore, the area is undergoing many developmental activities that have resulted in the movement of heavy machinery and coming up of roads [37, 38]. This has resulted in socio-economic changes and modernization in the area.

Surveys

The work involved field surveys, interactions with Bhangalis, recording of data, analyses, and interpretation of the collated information. Field surveys to the study area were conducted from January 2016 to March 2017. In the initial reconnaissance surveys seven villages were identified for intensive interviews and fieldwork (Table 1). These villages are representative of the area and are located on both the banks of river Lambadug. These were selected following our earlier work in the area [39–41]. Door-to-door surveys in these villages were conducted and information on age, gender, literacy, and use of WEP was collected using structured interviews [42]. Besides, focus group discussions were also held in each village. This involved free listing of WEP and detailed notes on their methods of preparation [43]. For this, prior informed consent was taken from the people and they were informed about the purpose and nature of the study. An oral agreement to participate in the study was received from them.

Table 1.

General profile of the village

| Serial no. | Name of village | Latitude | Longitude | Altitude (meters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Termehr | 32°04′28.606″ | 76°51′19.858″ | 2100 |

| 2. | Swad | 32°05′09.307″ | 76°50′58.927″ | 2295 |

| 3. | Bhujling | 32°06′03.73″ | 76°51′14.880″ | 2180 |

| 4. | Punag | 32°05′35.753″ | 76°51′20.954″ | 2230 |

| 5. | Andarli Malahn | 32°04′24.762″ | 76°52′01.67″ | 2200 |

| 6. | Napotha | 32°03′58.608″ | 76°51′41.750″ | 2120 |

| 7. | Judhar | 32° 04′42.06″ | 76° 50′50.001″ | 2450 |

Based on household surveys (n = 423), an inventory of WEP used by the local people was prepared (Table 2). Based on the purpose of use, these WEP were then categorized into six categories, namely, vegetables, fruits, chutney, flavoring food, raw food, and local brew (Table 3) [27, 44]. Top three to five most referred WEP in each of the category were identified for detailed analyses and documentation [31]. Thus, 20 plant species that includes a fungus were prioritized for analyzing trends and motivations behind their use [45]. Considering that local people classify fungi as a plant, the same was analyzed along with plants. For trend analyses, 176 villagers including men and women of different ages were randomly selected [30, 31]. Personal interactions using structured questionnaires were then conducted with these identified villagers (n = 176). Information on consumption of WEP in the past and present times was recorded. Additionally, motivations behind using WEP and reasons for their abandonment were also noted.

Table 2.

Wild edible plants consumed in Chhota Bhangal

| S. no. | Botanical name (family, collection number) |

Local name | Life form | Part used | Use | Frequency of use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Aesculus indica Hook. (Sapindaceae, PLP 9927) |

Khnor | Tree | Fruits | Fruits are ground to make a flour called “seek.” Seek is then kneaded with water to prepare dish for pregnant women. | Occasionally |

| 2. |

Allium humile Kunth. (Amaryllidaceae, PLP 9963) |

Pangri | Herb | Leaves | Thinly chopped fresh leaves are used for flavoring food. | Rarely |

| 3. |

Allium stracheyi Baker (Amaryllidaceae, PLP 9964) |

Van lahsun | Herb | Leaves | Finely chopped fresh leaves used for infusing flavor. | Occasionally |

| 4. |

Amaranthus paniculatus L. (Amaranthaceae, PLP 9955) |

Chaulai | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are cut, fried in mustard oil, and mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 5. |

Angelica glauca Edgew. (Apiaceae, PLP 9941) |

Chora | Herb | Roots | Crushed roots are used for flavoring food. | Frequently |

| 7. |

Berberis lyceum Royle (Berberidaceae, PLP 9937) |

Kashmal | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 6. |

Berberis aristata DC. (Berberidaceae, PLP 9950) |

Shamle | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 8. |

Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae, PLP 9945) |

Bhangolu | Herb | Seeds | Seeds are roasted and then consumed with sugar. | Occasionally |

| 9. |

Capsella bursa-pastoris Medik. (Brassicaceae, PLP 9965) |

Jangli sarson | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are roughly cut, boiled, and fried in mustard oil. Spices are added as per taste. | Rarely |

| 10. |

Chenopodium album L. (Chenopodiaceae, PLP 9931) |

Bathu | Herb | Leaves and seeds | Fresh leaves are roughly cut, boiled, and fried in mustard oil. Spices are added as per taste. Seed also used for making flour. | Occasionally |

| 11. |

Cirsium wallichii DC. (Asteraceae, PLP 9946) |

Bursa | Herb | Inflorescence | Freshly plucked inflorescence is eaten as such by children. | Rarely |

| 12. |

Colocasia esculenta Schott (Araceae, PLP 9961) |

Kachalu | Herb | Whole plant | Young fresh leaves are chopped and boiled. They are later fried in mustard oil and spices are added to it. Tubers locally called “kachalu” are also boiled and then fried in mustard oil. | Frequently |

| 13. |

Cotoneaster rotundifolius Wall. Ex. Lindl. (Rosaceae, PLP 9962) |

Riunsh | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Rarely |

| 14. |

Diplazium maximum (D.Don) C. Chr. (Dryopteridaceae, PLP 9966) |

Lengadu | Fern | Young fronds (leaves) | Young and immature fronds are wiped with cloth to remove hairs and then cut into pieces and fried. While cooking spices are added. Also used for making pickles. | Almost daily (in rainy season) |

| 15. |

Fagopyrum esculentum Moench. (Polygonaceae, PLP 9952) |

Fafra | Herb | Leaves | Fresh and young leaves are chopped, boiled and fried in mustard oil. Spices are added as per taste. In addition, the dried leaves are stored and used for making vegetable in winters. | Frequently |

| 16. |

Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (Apiaceae, PLP 9958) |

Sounp | Herb | Seeds | Seeds are used to flavor tea. | Frequently |

| 17. |

Fragaria nubicola Lacaita (Rosaceae, PLP 9930) |

Ban aakhre | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Occasionally |

| 18. |

Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae, PLP 9936) |

Tilfad | Herb | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Occasionally |

| 19. |

Juglans regia L. (Juglandaceae, PLP 9959) |

Khod | Tree | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 20. |

Mentha longifolia(L.) Huds. (Lamiaceae, PLP 9933) |

Jangli pudina | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are used for making chutney and also used to flavoring tea. They are ground on stone bed and spices are added to it. | Frequently |

| 21. |

Morchella esculenta Pers. (Morchellaceae, PLP 9967) |

Guchchi | Fungus | Fruiting body | Fruiting body is chopped into pieces, boiled and then fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 22. |

Oxalis corniculata L. (Oxalidaceae, PLP 9968) |

Almori | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are eaten by children. | Frequently |

| 23. |

Oxalis latifolia Kunth (Oxalidaceae, PLP 9940) |

Malori | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are eaten by children. Fresh leaves are also used for making chutney. | Frequently |

| 24. |

Oxyria digyna (L.) Hill (Polygonaceae, PLP 9969) |

Chhoti Chukri | Herb | Leaves | Leaves are chopped into pieces and are used to make chutney. | Occasionally |

| 25. |

Phytolacca acinosa Roxb. (Phytolaccaceae, PLP 9953) |

Jharkha | Herb | Leaves | Leaves are chopped and boiled. After boiling they are fried in mustard oil and then mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 26. |

Pinus roxburghii Sarg. (Pinaceae, PLP 9970) |

Cheeltu | Tree | Seeds | Seeds are eaten raw. | Rarely |

| 27. | Pinus wallichiana A.B. Jacks. (Pinaceae, PLP 9949) | Cheeltu | Tree | Seeds | Seeds are eaten raw. | Rarely |

| 28. |

Pleurotus sp. (Fr.) P. Kumm. (Pleurotaceae, PLP 9971) |

Kyaun | Fungus | Fruiting body | The fungus is chopped into pieces, boiled and then fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. The fungus grows abundantly on Ulmus wallichiana. | Frequently |

| 29. |

Prinsepia utilis Royle (Rosaceae, PLP 9944) |

Bhekal | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Rarely |

| 30. |

Prunus armeniaca L. (Rosaceae, PLP 9938) |

Shaade | Tree | Fruits | Ripe fruits and nuts are eaten. | Frequently |

| 31. |

Prunus cornuta Steud. (Rosaceae, PLP 9929) |

Jamnu | Tree | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 32. |

Prunus persica Batsch (Rosaceae, PLP 9960) |

Aaru | Tree | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Occasionally |

| 33. |

Pyrus pashia Buch.-Ham. Ex D.Don. (Rosaceae, PLP 9932) |

Shegal | Tree | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Occasionally |

| 34. |

Rheum australe D. Don (Polygonaceae, PLP 9972) |

Chambu | Herb | Leaves | For making vegetable, leaves are chopped into pieces, boiled and fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 35. |

Rhododendron arboreum Sm. (Ericaceae, PLP 9954) |

Braah | Tree | Flower | Flowers are used to make chutney with mint and also dried under sun for use in future. | Frequently |

| 36. |

Rosa canina L. (Rosaceae, PLP 9951) |

Jangli Gulaab | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Occasionally |

| 37. |

Rubus ellipticus Sm. (Rosaceae, PLP 9973) |

Aakhre | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 38. |

Rubus foliolosus D. Don (Rosaceae, PLP 9943) |

Aakhre | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Frequently |

| 39. |

Rumex dentatus L. (Polygonaceae, PLP 9957) |

Milu | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are eaten by children. | Frequently |

| 40. |

Rumex hastatus D. Don (Polygonaceae, PLP 9939) |

Jhemlu | Herb | Aerial part | Aerial parts are eaten raw and also used for making chutney with mint. | Frequently |

| 41. |

Selinum tenuifolium Wall. ex C.B. Clarke. (Apiaceae, PLP 9956) |

Matoshal | Herb | Roots | Locally called dheli, roots are used in making local brew. | Rarely |

| 42. |

Silene vulgaris Garcke (Caryophyllaceae, PLP 9974) |

Bibdughas | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are chopped and boiled. After boiling, fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 43. |

Sonchus asper Hill (Asteraceae, PLP 9934) |

Dudala | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are chopped and boiled. After boiling, fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Occasionally |

| 44. |

Stellaria media Vill. (Caryophyllaceae, PLP 9942) |

Khokhua | Herb | Aerial parts | Aerial parts are chopped, boiled and fried in mustard oil. Spices are added while cooking. | Frequently |

| 45. |

Taraxacum officinale Weber ex F.H. Wigg. (Asteraceae, PLP 9935) |

Shershi | Herb | Leaves | Fresh leaves are chopped into pieces and boiled. After boiling they are fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Frequently |

| 46. |

Taxus baccata subsp. wallichiana (Zucc.) Pilg. (Taxaceae, PLP 9948) |

Rakhal | Tree | Bark and leaves | Bark and leaves of Rakhal are used for flavoring tea. | Occasionally |

| 47. |

Thymus linearis Benth. (Lamiaceae, PLP 9975) |

Van Ajwain | Herb | Seeds | Seeds are used for flavoring tea. | Frequently |

| 48. |

Urtica dioica L. (Urticaceae, PLP 9928) |

Kushak | Herb | Young leaves | Young and fresh leaves are chopped into pieces, boiled and then fried in mustard oil and mixed with spices. | Rarely |

| 49. |

Viola pilosa Blume (Violaceae, PLP 9947) |

Banaksha | Herb | Flower and leaves | Flower and leaves of banaksha are used for flavoring tea. | Occasionally |

| 50. |

Zanthoxylum armatum DC. (Rutaceae, PLP 9976) |

Tirmir | Shrub | Fruits | Ripe fruits are eaten. | Rarely |

Table 3.

Wild edible plant categories and their characteristics

| WEP category | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Vegetables | Species that are cooked as food |

| Fruits | Species of which fresh/dry fruits are consumed without cooking |

| Chutney | Species ground with salt and spices for preparing sauce |

| Flavoring food | Species used for seasoning and infusing aroma |

| Raw food | Species in which fresh plant part, other than fruit, is eaten raw such as salad |

| Local brew | Species used to prepare liquor |

Data so collected were analyzed for species richness, taxonomic diversity, and plant part used for edible purposes. Analyses of trends of WEP use were also done. These trends/patterns were categorized into continuing use, declining use, increasing use, and not used (Table 4). The motivations/reasons behind these trends were then identified. These motivations encompass explanations pertaining to environment, economy, sociocultural, agriculture and land use changes, and human-wildlife conflict (Table 5). Voucher specimens were collected and have been deposited in the herbarium of CSIR-Institute of Himalayan Bioresource Technology, Palampur (Acronym PLP).

Table 4.

Categorization of use trends

| Trend | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Continuing use | Species that were consumed earlier and are still consumed in similar proportions |

| Declining use | Species that were consumed in higher amounts earlier (5 years) but now less used |

| Increasing use | Species that were consumed in lesser amount in the past but now more used |

| Not used | Species that were used earlier but are not used now |

Table 5.

Characteristics of different motivation categories

| Motivation category | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Environmental | Explanations related to factors such as climate, abundance and scarcity |

| Economic | Explanations pertaining to factors such as price, market value, and commercial availability |

| Sociocultural | Explanations related to taste, aroma, flavor, health, ritual, and interest |

| Agriculture and land use practices | Explanations related to changing agriculture and land use such as cultivation of cash crops, etc. |

| Human-wildlife conflict | Explanations related to crop depredation by wild animals, attacks by wild animals on humans, etc. |

Results

WEP diversity

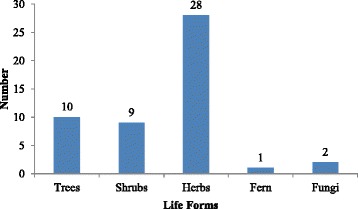

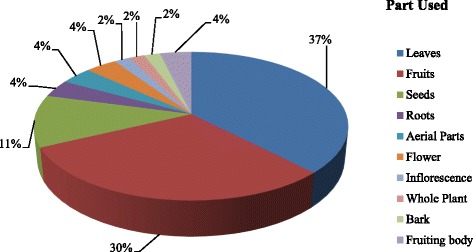

The Bhangalis reported use of 50 plant species belonging to 42 genera falling under 28 families as WEP. Majority of these belong to family Rosaceae (10 spp.) followed by Polygonaceae (5 spp.), Apiaceae, and Asteraceae (3 spp. each). Oxalidaceae, Lamiaceae, Pinaceae, Berberidaceae, Caryophyllaceae, and Amaryllidaceae were represented by two species each. Remaining families (n = 17) had one species each (Table 2). Herbs dominated the WEP that were consumed (n = 28, 56%) followed by trees (n = 10, 20%) and shrubs (n = 9, 18%). One species of fern (2%) and two species of fungi (4%) were also eaten (Fig. 1). Among the plant parts used, mostly leaves were used for different preparations (n = 20 species, 37%) followed by fruits (n = 16 species, 30%), seeds (n = 6 species, 11%), and fruiting bodies (n = 2 species, 4%). Roots, aerial parts, and flowers of two species each (4%) were used. Inflorescence, whole plant and bark were the least used parts (n = 1 species each, 2%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Life form categorization of the species used in Chhota Bhangal

Fig. 2.

Statistics of different plant parts used

Overall, mean number of species listed and used per respondent was 23.7 (median − 21) and 22.3 (median − 21), respectively. Most of these were used as vegetable (mean − 8.9, median − 9) followed by fruits (mean − 6.3, median − 6). An average of 3.2 species (median − 3) were used as chutney whereas the mean number of species used as flavoring foods was 2.2 (median − 2). The average number of species per respondent in case of raw food and local brew was 1.4 (median − 1) and 0.4, respectively.

Trends in WEP consumption

As mentioned in methods, of the total 50 WEP, 20 species were prioritized for trend analyses. These include four used as vegetables, five as fruits, and four each as chutney and flavoring food, three as raw food, and one species as local brew (Table 6). Oxalis latifolia was used both as raw food and chutney. Species falling under the head fruits and raw food were consumed as such by the people. These include Berberis aristata, Juglans regia, Oxalis corniculata, Oxalis latifolia, Prunus armeniaca, Prunus cornuta, Rubus ellipticus, and Rumex dentatus. Plants collected for other purposes were consumed after processing. The study revealed that more than 50% of the respondents had ever consumed the prioritized WEP in the area during their lifetime.

Table 6.

Prioritized plant species in different WEP categories

| Categories | Botanical name | Local name |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetables | Fagopyrum esculentum | Fafra |

| Diplazium maximum | Lengadu | |

| Pleurotus sp. Wild mushroom on Ulmus wallichiana | Kyaun | |

| Colocasia esculenta | Kachalu | |

| Fruits | Prunus armeniaca | Shaade |

| Juglans regia | Khod | |

| Rubus ellipticus | Aakhre | |

| Berberis aristata | Shamle | |

| Prunus cornuta | Jamnu | |

| Chutney | Rhododendron arboreum | Braah |

| Mentha longifolia | Jangli pudina | |

| Rumex hastatus | Jhemlu | |

| Oxalis latifolia | Malori | |

| Flavoring food | Angelica glauca | Chora |

| Viola pilosa | Banaksha | |

| Foeniculum vulgare | Sounp | |

| Thymus linearis | Van ajwain | |

| Raw food | Oxalis corniculata | Almori |

| Rumex dentatus | Milu | |

| Oxalis latifolia | Malori | |

| Local brew | Selinum tenuifolium | Matoshal |

Among the six WEP categories, most of the respondents (68.75%) favored continuing use of chutney and only 5.68% respondents favored continuing use of WEP for local brewing. With respect to vegetables, 64.77% of the respondents reported a continuing use trend while 35.23% revealed its declining use (Table 7). On comparing continuing and declining use, highest number of respondents in all the WEP categories were for continuing use barring flavoring food and local brew, where the percentage of respondents was highest for declining use, i.e., 54.55 and 50.57%, respectively (Table 7). In case of chutney, an increasing use trend was observed. Close to 23 % of the respondents who were not consuming it earlier are now consuming it. This was the only WEP category in which an increasing use trend was recorded (Table 7). It was found that few respondents had not used the prioritized plant species during the past 5 years. This includes 1.14% of the respondents for chutney category, 7.95% for flavoring food, 9.66% for raw food, and 43.75% for the local brew.

Table 7.

Trends in use (%) across different WEP categories

| WEP category | Trends | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuing use | Declining use | Increasing use | Not used | |

| Vegetable | 64.77 | 35.23 | – | – |

| Fruits | 68.18 | 31.82 | – | – |

| Chutney | 68.75 | 6.82 | 23.30 | 1.14 |

| Flavoring food | 37.50 | 54.55 | – | 7.95 |

| Raw food | 50.57 | 39.77 | – | 9.66 |

| Local brew | 5.68 | 50.57 | – | 43.75 |

| Total | 49.24 ± 10.03 | 36.46 ± 6.93 | 3.88 ± 3.88 | 10.42 ± 6.88 |

None of the respondents reported of having not used the prioritized vegetables and fruits during the past 5 years.

Overall, irrespective of the WEP category, 49.24% of respondents continue use of WEP while 10.42% reported not using them now. Declining use of WEP was reported by 36% of the respondents (Table 7).

Motivations for WEP consumption

There were a total of 1341 responses offered by the 176 respondents for motivations that inspire or limit WEP consumption. A similar response given by two different respondents has been counted as two individual responses. As detailed in the methods, all these responses have been clubbed under five different motivation categories, namely, environmental, economy, sociocultural, agriculture and land use changes, and human-wildlife conflict.

Of the total 1341 responses, 743 (55.41%) were for motivations leading to the continuing use of WEP, while 529 (39.45%) were for their declining use (Table 8). Highest number of responses (82.55%) fall under the sociocultural motivation category and lowest under the agriculture and land use changes category. Environmental motivations accounted only for 11.48% of the total responses, while only 2.83% cited the economic motivations (Table 8).

Table 8.

Responses under different motivation categories that guide WEP use

| Motivation category | Trends for consumption | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuing | Declining | Increasing | Total | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Environmental | 42 | 3.13 | 112 | 8.35 | 0 | 0 | 154 | 11.48 |

| Economic | 31 | 2.31 | 7 | 0.52 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 2.83 |

| Sociocultural | 670 | 49.96 | 368 | 27.44 | 69 | 5.15 | 1107 | 82.55 |

| Agriculture and land use changes | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.37 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0.37 |

| Human-wildlife conflict | 0 | 0 | 37 | 2.76 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 2.76 |

| Total | 743 | 55.41 | 529 | 39.45 | 69 | 5.15 | 1341 | 100.00 |

With respect to continuing, declining, and increasing use, highest responses, i.e., 670 (49.96%), 368 (27.44%) and 69 (5.15%), respectively fall under the sociocultural motivation category (Table 8). Responses under motivation categories agriculture and land use changes (0.37%), and human-wildlife conflict (2.76%) accounted only for declining use of WEP (Table 8).

Motivation explanations

It was observed that WEP consumption was guided by 25 motivation explanations under the five motivation categories (Table 9). Sociocultural category accounted for largest number of the explanations (n = 17) followed by environmental (n = 3), economic and human-wildlife conflict (n = 2 each), and agriculture and land use changes (n = 1) (Table 9). With respect to consumption trends, out of 25 motivation explanations, 9 explanations were for continuing use, while 12 were for declining use, and the remaining for increasing use. As pointed earlier, only WEP chutney category had an increasing use trend. Here-in four explanations were given for increasing use by 41 respondents. Of the 17 explanations that represented sociocultural motivation category, 7 were for continuing use, 6 for decreasing use, and 4 for increasing use of WEP (Table 9).

Table 9.

People’s responses and explanations that guide WEP consumption in the area

| Motivation category | Motivation explanation | Trend | Example | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 1. It is abundantly and easily available | Continue | They are in large quantity | 42 | 3.13 |

| 2. It is scare due to changing environment | Decline | They are few because of low/high rainfall | 70 | 5.22 | |

| 3. Difficult to access | Decline | Grows at high altitude | 42 | 3.13 | |

| Economic | 4. It is free of cost | Continue | We do not pay for it | 31 | 2.31 |

| 5. Now not available in the local market | Decline | It is sold out of local market | 7 | 0.52 | |

| Sociocultural | 6. Lovely aroma and flavor | Continue | I love it | 45 | 3.36 |

| 7. Good and yummy taste | Continue | It is so tasty | 490 | 36.54 | |

| 8. Local food | Continue | It is a food of our area | 4 | 0.30 | |

| 9. Traditional culture | Continue | It is in our tradition | 21 | 1.57 | |

| 10. Healthy nature | Continue | It is good for our health | 43 | 3.21 | |

| 11. Having medicinal properties | Continue | It is good for stomach | 47 | 3.50 | |

| 12. It is eaten for the sake of interest | Continue | I am interested in eating it | 20 | 1.49 | |

| 13. Tasteless and bad aroma | Decline | I do not love it | 5 | 0.37 | |

| 14. Lack of knowledge about plant | Decline | I do not have much knowledge about the plant | 71 | 5.29 | |

| 15. Market availability | Decline | It is replaced by market goods | 22 | 1.64 | |

| 16. Culture and lifestyle changes | Decline | Our diets have changed | 222 | 16.55 | |

| 17. Restrictions for eating | Decline | It is unhealthy | 5 | 0.37 | |

| 18. Large time is needed to collect it/waste of time | Decline | I do no collect it | 43 | 3.21 | |

| 19. Good and yummy taste | Increase | It is tasty | 25 | 1.86 | |

| 20. Culture and lifestyle changes | Increase | I am interested in eating it | 39 | 2.91 | |

| 21. Healthy nature | Increase | It is good for health | 1 | 0.07 | |

| 22. Having medicinal properties | Increase | It is good for stomach | 4 | 0.30 | |

| Agriculture and land use changes | 23. Changes in agricultural activities | Decline | Changed agricultural practices reduce availability of WEP | 5 | 0.37 |

| Human-wildlife conflict | 24. Animal destruction | Decline | Monkey destroy them | 32 | 2.39 |

| 25. Human disturbance | Decline | Forest destruction by humans | 5 | 0.37 | |

| Total | 1341 | 100 |

In general, it was observed that out of the total responses, highest (36.54%) were related to taste and were instrumental in continuing consumption of WEP. Close to 17% of the responses were related to changing lifestyle that accounted for declining use of WEP (Table 9). Both of these represent the sociocultural motivation category. Lack of knowledge regarding the specific use of plants species (5.29%), and reduced availability of species due to changing environmental conditions (5.22%) were the other common responses behind the declining use of WEP (Table 9). Local interest and preference for taste were the two main reasons (2.91 and 1.86%, respectively) for the increasing use of WEP (Table 9). Free availability (2.31%) also had a role to play in continuing use. Changes in land use practices (0.37%), and human-wildlife conflicts such as forest degradation, attacks on humans, and crop depredation by wild animals also resulted in the declining use of WEP (2.76%) (Table 9).

Discussion

Wild edible plants continue to satiate human diet especially in interior areas such as the Himalaya [24]. Out of the total 323 plant species reported to be edible in the entire state of Himachal Pradesh [46], almost 15% are used by the Bhangalis. Close to 50% of the respondents reported use of WEP. Studies among the Tibetan communities in Gansu province of China have shown use of 54 wild vascular plant species for edible purposes. The mean and median of wild edible plants used in the area was 20.8 and 21, respectively [47]. In the present study, though total number of WEP species reported was comparatively low (50), mean of WEP used was higher (22.3). On the other hand, in Poljica and Krk islands, Croatia total number of wild edible species used was higher [48]. However, mean species used per interview was low [47, 48]. It reveals that local people individually use more species in the present study area. In Imereti region of Western Georgia, 53 wild species with a mean of 10.4 species per interview have been reported to be used for edible purposes [49]. Similar results have also been presented from the Gongba Valley of China [11].

Alike other studies, vegetables formed a prime component of WEP in the area. In the present area, mean number of species used as vegetables per respondent (8.8) was higher than mean number of species used in any other WEP category. Here, alike other Himalayan regions, people dry the seasonally available vegetables for use during periods of snowfall [11]. This shows the importance of plants for sustenance and nutrition in the interior areas. A mean of 7.5 species per interview has been reported to be used as vegetables in the Gansu province of China [47], while 8.7 species of green vegetables per interview has been reported to be used in Gongba valley of China [11]. At the same time, similar mean number of species as in the present area (6.3) have been reported to be used as fruits in the Gansu province of China (6.3). In Gongba valley of China and Imereti region of Western Georgia, mean number of species used as fruits is 6.9, each [11, 47, 49].

Trends in changing WEP use patterns are evident in the area as has been reported from across the globe [8, 32, 50]. Declining use of WEP has severe implications for future prospections and leads to narrowing of genetic base [9, 30, 31]. In the present study, people reported increasing use of WEP as chutney (23.30%), more than 50% reported a declining use of WEP as flavoring food (54.55%) and also as local brew (50.57%). The reasons for this could be low populations of flavoring food species and the extra effort required for their collection. Findings from Saaremaa, Estonia show similar patterns where people would not like to go to distant places and search for WEP now [51]. In Patagonia, South America also targeted efforts for collecting wild foods has limited their gathering and use [52]. At times, regulations also have a role to play in declining use of WEP. In the present area, local alcohol brewing requires permission, otherwise it is illegal. In Catalan Pyrenees and Balearic Islands also restrictions were pointed as a reason leading to declining use of WEP [31]. Increasing use trend of chutney may be because WEP used for making chutney are often found around villages and are required in low quantity. Few workers have also reported such an increase in consumption of specialized plant species where the volume required is low [30]. In the present area, Aesculus indica is used as a specialized food for expecting mothers. The fruits of this plant are thoroughly washed, dried, and ground. The flour so obtained is used for making the recipe—seek. Use and preparation of the recipe has been provided in a separate publication by the authors [40]. Studies on WEP that require specialized processing are now receiving much attention. This has been discussed in detail for the comfrey and buttercup eaters of the Imereti region, Western Georgia [49].

Irrespective of the WEP category, sociocultural motivations were found to play an important role in defining continuing, declining, and increasing use of WEP in the present study. Elsewhere also, studies have highlighted sociocultural factors to play a major role in WEP use [23, 25, 30, 53]. In the Catalan Pyrenees and Balearic Islands, taste was reported to be a prime motivation for continuing consumption of WEP while lifestyle changes led to abandonment of WEP consumption [31]. In Saaremaa, Estonia also use of WEP have been related to taste [51] while the disappearance of familiar taxa from surrounding areas has been linked to their declining use [51]. Similarly, while taste and aroma were the major sociocultural motivations for continuing use of WEP in the present study, changing lifestyle pattern was the prime reason for their declining use. Many studies have noted the importance of traditional culture in maintenance of WEP consumption [54, 55]. In Iberian Peninsula, despite an overall decreasing trend, uses of WEP of high cultural appreciation and recreation was found to be still maintained [30]. On the other hand, modern lifestyle and market availability of resources have limited the use of WEP [21, 28, 29, 56–58]. In some areas, collection of WEP is now seen as something that is old fashioned [59]. Interestingly, we found, people prefer to sell WEP in the market and earn hard cash rather than consume WEP themselves (Figs. 3 and 4). As reported, market forces and changes in agriculture and land use practices affect traditional lifestyle and WEP use [60, 61]. In the present area, cash crops are replacing traditional crops and thus land use changes are also responsible for declining use of WEP. Conversion of forest land and degradation of resources leads to human-wildlife conflict, which in turn also limits WEP use. In Saaremaa, Estonia, though in minor proportions, the fear of poisonous snakes and insects has limited the use of WEP [51]. This has also been noted in Catalan Pyrenees and the Balearic Islands [31], and in Rio Grande do Sul, south Brazil [62].

Fig. 3.

Flowers of Rhododendron being sold in the market for making chutney

Fig. 4.

Fronds of Diplazium put up for sale (extreme left)

In the present study, close to 3% of the responses point to easy access and large population as prime reasons behind consumption of WEP. This clearly indicates that people do not like to wander into the interiors for searching WEP. They would rather prefer using plants that are available in their vicinity. It has been pointed out that free and easy availability of resources motivates its use by the local inhabitants [59]. Further, WEP with multiple utility such as associated health benefits are preferred for consumption [26, 51]. In Patagonia, changing environmental conditions are documented to have negatively affected WEP consumption [63]. Interestingly, in the present area also people cited that shortfall in rains has resulted in a decline in availability of some species (especially ferns). This consequently, has limited their use.

Conclusion

The study concludes that though use of wild edible plants is still maintained in the area, a change in consumption trends is evident. Sociocultural motivations were found to play a prime role in, both, limiting and promoting WEP consumption. While taste and aroma were the major sociocultural reasons behind using WEP, modernization, and changing lifestyle were the main reasons behind declining use of WEP.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Director CSIR-IHBT for the facilities and encouragement. Faculty members of the High Altitude Biology Division are acknowledged for their support and valuable comments. Thanks are also due to the Editor and Reviewer’s whose comments and suggestions helped in improving the manuscript. We thank the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change; Government of India for financial support via National Mission on Himalayan Studies through project GAP-0199. This is IHBT communication number 4163.

Funding

Funds for the study were provided by the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change India via National Mission on Himalayan Studies through project GAP-0199.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- NMHS

National Mission on Himalayan Studies

- PLP

Palampur

- WEP

Wild Edible Plants

Authors’ contributions

DK and AS carried out field surveys and data recording. SKU designed the study and prepared the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deepika Thakur, Email: thakurdeepika424@gmail.com.

Alpy Sharma, Email: sharmaalpy@gmail.com.

Sanjay Kr. Uniyal, Email: suniyal@ihbt.res.in

References

- 1.Menendez-Baceta G, Aceituno-Mata L, Taedio J, Reyes-Garcia V, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country) Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2012;59(7):1329–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10722-011-9760-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heywood VH. Use and potential of wild plants in farm households. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levetin E, McMahon K. Plant and society. 5. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redzic S, Barudanovic S, Pilipovic S. Wild mushrooms and lichens used as human food for survival in war conditions: Podrinje-Zepa region (Bosnia and Herzegovina, W. Balkan) Hum Ecol Rev. 2010;17(2):175. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner NJ, Luczaj LJ, Migliorini P, Pieroni A, Dreon AL, Sachhetti LE, Paoletti MG. Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2011;30(1–2):198–225. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghirardini MP, Carli M, Del Vecchio N, Rovati A, Cova O, Valigi F, Audini F. The importance of taste. A comparative study on wild food plants consumption in twenty-one local communities in Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi N, Siwakoti M, Kehlenbeck K. Wild vegetable species in Makawanpur District, Central Nepal: developing a priority setting approach for domestication to improve food security. Econ Bot. 2015;69(2):161–170. doi: 10.1007/s12231-015-9310-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigat M, Bonet MAN, Garcia S, Garnatje T, Valles J. Ethnobotany of food plants in the high river Ter valley (Pyrenees, Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): non-crop food vascular plants and crop food plants with medicinal properties. Ecol Food Nutr. 2009;48(4):303–326. doi: 10.1080/03670240903022320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortolotto IM, Mello de Amorozo MC, Neto GG, Oldeland J, Damasceno-Junior GA. Knowledge and use of wild edible plants in rural communities along Paraguay River, Pantanal, Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2015;11(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ju Y, Zhuo J, Liu B, Long C. Eating from the wild: diversity of wild edible plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan, China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(1):28. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang Y, Luczaj L, Kang J, Wang F, Hou J, Guo Q. Wild food plants used by the Tibetans of Gongba Valley (Zhouqucounty, Gansu, China) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;10(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asfaw Z. International symposium on underutilized plants for food security, nutrition, income and sustainable development. 2008. The future of wild food plants in southern Ethiopia: ecosystem conservation coupled with enhancement of the roles of key social groups; pp. 701–708. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maundu PM. The biodiversity of African plants. 1996. Utilization and conservation status of wild food plants in Kenya; pp. 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grivetti LE, Ogle BM. Value of traditional foods in meeting macro and micro nutrient needs: the wild plant connection. Nutr Res Rev. 2000;13(1):31–46. doi: 10.1079/095442200108728990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burlingame B. Wild nutrition. J Food Compos Anal. 2000;13(2):99–100. doi: 10.1006/jfca.2000.0897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badhwar RL, Fernandez RR. Edible wild plants of the Himalayas. Delhi: Daya publishing House; 2011.

- 17.Saha D, Sundriyal M, Sundriyal RC. Diversity of food composition and nutritive analysis of edible wild plants in a multi-ethnic tribal land, Northest India: an important facet for food supply. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2014;13(4):0975–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jana SK, Chouhan AS. Wild edible plants of Sikkim Himalaya. J Non-timber Forest Prod. 1998;5:20–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samant SS, Dhar U. Diversity, endemism and economic potential of wild edible plants of Indian Himalaya. Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol. 1997;4(3):179–191. doi: 10.1080/13504509709469953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundriyal M, Sundriyal RC, Sharma E, Porohit AN. Wild edibles and other useful plants from the Sikkim Himalaya, India. Oecol Montana. 1998;7(1–2):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharucha Z, Pretty J. The roles and values of wild food plants in agricultural systems. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2010;365(1554):2913–2926. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johns T, Kokwaro JO, Kimanani EK. Herbal remedies of the Luo of Siaya District, Kenya-establishing quantitative criteria for consensus. Econ Bot. 1990;44:369–381. doi: 10.1007/BF03183922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pardo-De-Santayana M, Tardi J, Blanco E, Carvalho AM, Lastra JJ, San Miguel E, Morales R. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): a comparative study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundriyal M, Sundriyal DC. Wild edible plants of Sikkim Himalaya. Nutritive values of selected species. Econ Bot. 2001;55(3):377–390. doi: 10.1007/BF02866561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luczaj L. Changes in the utilization of wild green vegetables in Poland since the 19th century: a comparison of four ethnobotanical surveys. J Ehnopharmacol. 2010;128(2):395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luczaj L, Pieroni A, Tardio J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Soukand R, Syanberg I, Kalle R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe, the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81(4):359-70.

- 27.Tardio J, Pascual H, Morales R. Wild food plants traditionally used in the province of Madrid, Central Spain. Econ Bot. 2005;59(2):122–136. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2005)059[0122:WFPTUI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benz BF, Cevallos EJ, Santana MF, Rosales AJ, Graf MS. Losing knowledge about plant use in the Sierra de Manantlan biosphere reserve, Mexico. Econ Bot. 2000;54(2):183–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02907821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luczaj L, Koncic MZ, Milicevic T, Dolina K, Pandza M. Wild vegetable mixes sold in markets of Dalmatia (Southern Croatia) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes-Garcia V, Menendez-Baceta G, Aceituno-Mata L, Acosta-Naranjo R, Calvet-Mir L, Dominguez P, Rodriguez-Franco R. From famine food to delicatessen: interpreting trends in the use of wild edible plants through cultural ecosystem services. Ecol Econ. 2015;120:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrasolses G, Calvet-Mir L, Carrio E, Ambrosio UD, Garnatje T, Parada M, Reyes-Garcia V. A matter of taste: local explanations for the consumption of wild food plants in the Catalan Pyrenees and the Balearic Islands 1. Econ Bot. 2016;70(2):176–189. doi: 10.1007/s12231-016-9343-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schunko C, Grasser S, Vogl CR. Explaining the resurgent popularity of the wild: motivations for wild plant gathering in the biosphere reserve grosses Walsertal, Austria. J Ethnobiol Ehnomed. 2015;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godoy R, Reyes-Garcia V, Byron E, Leonard WR, Vadez V. The effect of market economics on the well-being of indigenous peoples and on their use of renewable natural resources. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2005;34:121–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oraon V. Changing pattern of tribal livelihood: a case study in Sundargarh District, Odisha, India. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha D, Singh KI, Sundriyal RC. Non-timber forest products linked rural livelihood in West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh. In: Ramakrishnan PS, Sexena KG, Ks R, editors. Shifting agriculture and sustainable development of north-eastern India: tradition in transition. New Delhi: UNESCO. Oxford publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.; 2006. pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siva Prasad R, Eswarappa K. Tribal livelihood in a limbo: changing tribal-nature relationship in south Asia. 2007. pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- 37.EIA report of Lambadug hydro-electric power project (25MW) District Kangra (H.P.). 2006.

- 38.Gupta KK. Draft management plan of the Dhauladhar wildlife sanctuary (2004–2014) (HP) 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uniyal A, Uniyal SK, Rawat GS. Commercial extraction of Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle ex Benth. In the Western Himalaya. Mt Res Dev. 2011;31(3):201–208. doi: 10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-10-00125.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uniyal SK, Singh KN, Jamwal P, Lal B. Traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, Western Himalaya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uniyal SK, Kumar A, Lal B, Singh RD. Quantitative assessment and traditional uses of high value medicinal plants in Chhota Bhangal area of Himachal Pradesh, western Himalaya. Curr Sci. 2006;91(9):1238–1242. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin GJ. Ethnobotany: a method manual. London: Chapman and Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Shrestha KK, Rajbhandary S, Tiwari NN, Shrestha UB, Asselin H. Diversity of use and local knowledge of wild edible plant resources in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012;8(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tardio J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Morales R. Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linn Soc. 2006;152:27–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2006.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Misra S, Maikhuri RK, Kala CP, Rao KS, Saxena KG. Wild leafy vegetables: a study of their subsistence dietetic support to the inhabitants of Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008;4:15. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sood SK, Rawat D, Kumar S, Rawat S. Handbook of wild edible plants. Jaipur: Pointer Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang J, Kang Y, Ji X, Guo Q, Jacques G, Pietras M, Luczaj N, Li D, Luczaj L. Wild food plants and fungi used in mycophilous Tibetan community of Zhagana [Tewo County, Gansu, China] J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2016;12(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0094-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolina K, Jug-Dujakovic M, Luczaj L, Vitasovic-Kosic I. A century of changes in wild food plant use in coastal Croatia: the example of Krk and Poljica. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2016;85(3):3508. doi: 10.5586/asbp.3508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luczaj L, Tvalodze B, Zalkaliani D. Comfrey and buttercup eaters: wild vegetables of the Imereti Region in Western Georgia. Econ Bot. 2017;71(2):188–193. doi: 10.1007/s12231-017-9379-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parada M, Carrio E, Valles J. Ethnobotany of wild food plants in the alt Emporda region (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula) J Appl Bot Food Qual. 2012;84(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soukand R. Perceived reasons for changes in the use of wild food plants in Saaremaa, Estonia. Appetite. 2016;107:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ladio AH, Lozada M. Patterns of use and knowledge of wild edible plants in distinct ecological environments: a case study of a Mapuche community from northwestern Patagonia. Biodivers Conserv. 2004;13(6):1153–1173. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOC.0000018150.79156.50. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pieroni A. Evaluation of the cultural significance of wild food botanicals traditionally consumed in Northwestern Tuscany, Italy. J Ethnobiol. 2001;21(1):89–104. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schunko C, Vogl CR. Organic farmer’s use of wild food plants and fungi in a hilly area in Styria (Austria) J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seeland K, Staniszewski P. Indicators for European cross-country state-of-the-art assessment of non-timber forest products and services. Small Scale Forestry. 2007;6(4):411–422. doi: 10.1007/s11842-007-9029-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abbet C, Mayor R, Roguet D, Spichiger R, Hambuger M, Potterat O. Ethnobotanical survey on wild alpine food plants in lower and Central Valais (Switzerland) J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151(1):624–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez JA, Garcia-Barriuso M, Amich F. The consumption of wild and semi-domesticated edible plants in the Arribesdel Duero (Salamanca-Zamora, Spain): an analysis of traditional knowledge. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2011;58(7):991–1006. doi: 10.1007/s10722-010-9635-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalle R, Soukand R. Wild plants eaten in childhood: a retrospective of Estonia in the 1970s-1990s. Bot J Linn Soc. 2013;17(2):239–253. doi: 10.1111/boj.12051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pardo-De-Santayana M, Tardio J, Morales R. The gathering and consumption of wild edible plants in the Campoo (Cantabria, Spain) Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2005;56(7):529–542. doi: 10.1080/09637480500490731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Foley JA, Defries R, Asner GP, Barford C, Bonan G, Carpenter SR, Helkowski JH. Global consequences of land use. Science. 2005;309(5734):570–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1111772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Treweek JR, Brown C, Bubb P. Assessing biodiversity impacts of trade: a review of challenges in the agriculture sector. Impact Assess Proj Appraisal. 2006;24(4):299–309. doi: 10.3152/147154606781765057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rocha LC, Fortes VB. Perception and attitudes of rural residents towards capuchin monkeys, in the area of influence of the Dona francisca hydroelectric power plant, south Brazil. Ambiente Soc. 2015;18(4):19–34. doi: 10.1590/1809-4422ASOC825V1842015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ladio AH. The maintenance of wild edible plant gathering in a Mapuche community of Patagonia. Econ Bot. 2001;55(2):243–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02864562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.