Abstract

The transmembrane protein Cx43 has key roles in fibrogenic processes including inflammatory signaling and extracellular matrix composition. aCT1 is a Cx43 mimetic peptide that in preclinical studies accelerated wound closure, decreased inflammation and granulation tissue area, and normalized mechanical properties after cutaneous injury. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of aCT1 in the reduction of scar formation in human incisional wounds. In a prospective, multicenter, within-participant controlled trial, patients with bilateral incisional wounds (≥10 mm) after laparoscopic surgery were randomized to receive acute treatment (immediately after wounding and 24 hours later) with an aCT1 gel formulation plus conventional standard of care protocols, involving moisture-retentive occlusive dressing, or standard of care alone. The primary efficacy endpoint was average scarring score using visual analog scales evaluating incision appearance and healing progress over 9 months. There was no significant difference in scar appearance between aCT1- or control-treated incisions after 1 month. At month 9, aCT1-treated incisions showed a 47% improvement in scar scores over controls (Vancouver Scar Scale; P = 0.0045), a significantly higher Global Assessment Scale score (P = 0.0009), and improvements in scar pigmentation, thickness, surface roughness, and mechanical suppleness. Adverse events were similar in both groups. aCT1 has potential to improve scarring outcome after surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Scar formation is an inevitable outcome of wound healing and can result in undesirable changes in skin mechanical integrity and function, as well as cosmetic disfiguration. An estimated 322 million surgical procedures are required annually, often resulting in significant scarring (Rose et al., 2015). The appearance of the scar is of utmost importance to patients, often reported as a greater concern than a successful outcome of the surgical procedure (Bush et al., 2010a, 2010b). Currently, no single therapy is universally accepted as the standard of care (SOC) to reduce postsurgical scarring, and, with the recent exception of silicone steroid gels designed for the treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars (Chittoria and Padi, 2013; Medhi et al., 2013), no US Food and Drug Administration-approved products have produced consistent results for preventing, reducing, or eliminating excess deposition of scar tissue (Bush et al., 2011; Tziotzios et al., 2012).

Additional treatment options currently include regimens involving surgical revision, laser, radiation, corticosteroids, and alternative topical therapies that remain predominantly symptomatic, empirical, unpredictable, and largely ineffective (Bayat et al., 2003; Meier and Nanney, 2006; O’Brien and Jones, 2013). Because severity in scarring outcome is linked to intrinsic processes of wound healing, surgical revision commonly results in recurrence and evidence in support of the efficacy of laser therapies are largely anecdotal (Mustoe, 2004) and associated with conflicting reports of success (Smit et al., 2005); antiscarring therapies that act prophylactically to prevent poor outcome are needed. Systematic comparative review of current therapies is hampered by the fact that supporting clinical evidence from controlled prospective randomized studies are nonexistent or insufficient because of small samples, variable evaluation methods, and short follow-up (Baker et al., 2009; Monstrey et al., 2014; O’Brien and Jones, 2013). Although predominantly effective only in the treatment of keloids, intralesional injection of corticosteroids is the only invasive scar management option that currently has enough supporting evidence to be recommended in evidence-based guidelines (Middelkoop et al., 2011; Mustoe et al., 2002). Recently, a direct comparison of 39 clinical reports involving 1,703 patients showed little clinical evidence to support the efficacy of topical treatments including imiquimod, mitomycin C, and plant extracts such as onion extract, green tea, Aloe vera, vitamins E and D applied to healing wounds, mature scar tissue, or fibrotic scars after revision surgery or in combination with more established treatments such as steroid injections and silicone (Sidgwick et al., 2015). Those therapies that show clinically significant effects on scar appearance may be cumbersome, limited in efficacy to specific scar types, or associated with severe adverse effects for what is typically minor improvement (Baker et al., 2009; Monstrey et al., 2014; Tziotzios et al., 2012).

Research into fetal scarring and TGF-β shows the importance of early cellular signaling cascades in improving the architecture of the healing dermis and in scarring outcome (Ferguson and O’Kane, 2004). A large body of evidence support the role of connexins—a family of transmembrane proteins characterized by their capacity to form channels that directly link the cytoplasm of adjacent cells (gap junctions) or permit cell-extracellular paracrine communication (hemichannels)—as a potential antiscarring therapy (Ghatnekar et al., 2009; Qiu et al., 2003; Rhett et al., 2008). Cx43 is expressed in both epidermal and dermal cutaneous layers and has key regulatory assignments in wound repair and the processes of re-epithelialization, neovascularization, collagen deposition, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Churko et al., 2012; Cogliati et al., 2015; Ghatnekar et al., 2009; Hunter et al., 2005; Marquez-Rosado et al., 2012; Rhett et al., 2011). Hemichannels comprised of Cx43 are critical determinants of inflammatory, edematous, and fibrotic processes occurring in response to wounding, mediating purinergic signaling, and the release of proinflammatory and cytotoxic molecules (Calder et al., 2015; Lorraine et al., 2015; O’Carroll et al., 2013; Rhett et al., 2014). aCT1 is a 25-amino acid peptide designed to mimic the carboxyl terminus of Cx43 (Ghatnekar et al., 2009; Hunter et al., 2005; Rhett et al., 2011). At the molecular level, aCT1 inhibits the activity of Cx43 hemichannels by inducing their sequestration from the perinexus region surrounding gap junctions, thereby reducing hemichannel density and availability for activation within the cell membrane (Rhett et al., 2011). On the macroscopic level, aCT1 treatment of mouse and pig skin wounds increases wound closure rate, decreases inflammatory neutrophil infiltration, and reduces granulation tissue area (Ghatnekar et al., 2009). Published clinical trials on the use of aCT1 to treat diabetic foot and venous leg ulcers have shown efficacy in increasing re-epithelialization rates of both types of pathological wounds (Ghatnekar et al., 2015; Grek et al., 2015). Despite evidence that targeting Cx43 lowers granulation tissue deposition, no clinical studies have been conducted to evaluate therapeutic potential in scar prevention. We now report the results of a randomized, observer-blinded, within-participant control, multicenter proof-of-concept study aimed at assessing the efficacy and safety of topically delivered aCT1 in the reduction of scar formation in surgical wounds.

RESULTS

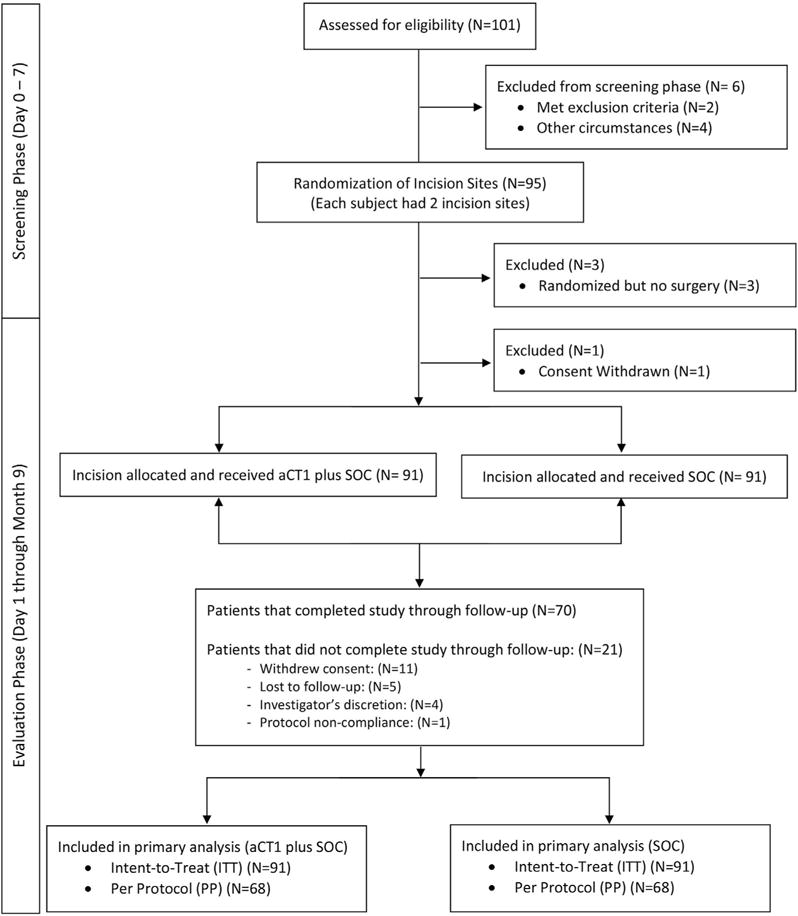

Eligible patients were recruited from October 1, 2011, through September 26, 2012, from seven centers in India. A total of 95 Asian Indian patients were selected for incision randomization to receive aCT1 treatment immediately and 24 hours later in association with SOC or SOC alone (Figure 1). Analyses of baseline demographics and clinical characteristics showed a higher number of female participants and the primary laparoscopic incision site locations as epigastric, hypochondrial, and umbilical (Table 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram.

Diagram describing study flow and patient disposition.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Clinical characteristics (N = 95) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| Mean (SD) | 38.5 (12.3) |

| Median | 39 |

| Range | 19–68 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 32 (34) |

| Female | 63 (66) |

| Weight, kg | |

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (24.0) |

| Median | 60 |

| Range | 34–175 |

| Height, cm | |

| Mean (SD) | 162.6 (9.2) |

| Median | 160 |

| Range | 144–192 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | |

| Mean (SD) | 25.1 (7.8) |

| Median | 22.8 |

| Range | 15–60 |

| Smoking habits, n (%) | |

| Yes | 3 (3) |

| No | 92 (97) |

| Clinical history (N = 92)1 |

| Incision location, n (%) | aCT1 + SOC | SOC | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigastric | 11 (12) | 19 (21) | 0.11 |

| Lefthypochondrial | 12 (13) | 14 (15) | 0.67 |

| Right hypochondrial | 15 (16) | 15 (16) | 1.00 |

| Left iliac | 10 (11) | 9 (10) | 0.81 |

| Right iliac | 7 (8) | 5 (5) | 0.55 |

| Left inguinal | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 0.70 |

| Right inguinal | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Paraumbilical | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 1.0 |

| Pre umbilical | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | — |

| Umbilical | 19 (21) | 15 (16) | 0.45 |

| Pubic | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.00 |

| Suprapubic | 6 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.31 |

| Right lumbar | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.56 |

| Incision size at baseline, mm | |||

| Mean(SD) | 12.4 (3.1) | 12.2 (2.8) | 0.70 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; SOC, standard of care.

Three patients were randomized but did not receive surgery.

Of the 95 patents selected for treatment randomization, one patient withdrew consent before efficacy assessments were completed, and three patients, although randomized, did not proceed with surgery. A total of 70 participants completed the study through follow-up. Primary and secondary analyses were conducted on intent-to-treat (ITT) (n = 91) and the per-protocol (PP) (n = 68) populations. The ITT population included all participants whose incision sites received at least one treatment and at least one wound assessment. The PP population consisted of those participants lacking major protocol deviation. Despite completing the study through follow-up, two participants were excluded from the PP population analyses because they met an exclusion criterion (i.e., HbA1c level > 9%).

Efficacy

Primary efficacy analyses: Vancouver Scar Scale

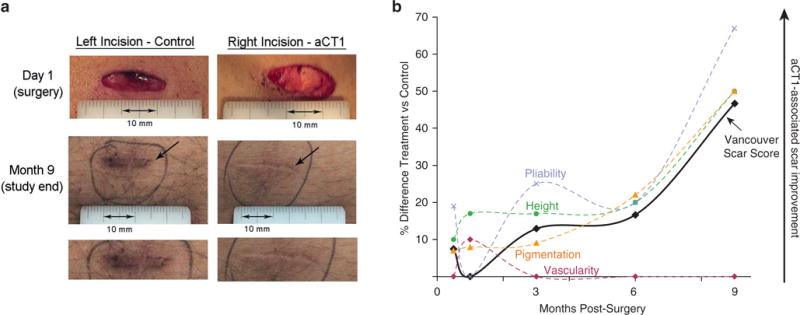

The primary efficacy endpoint was the average scarring score at 9 months using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS). Figure 2a provides representative images of paired treated and untreated laparoscopic scars from a participant immediately after surgery and at the final 9-month scar assessment. The mean VSS score of aCT1-treated incisions was significantly lower (47% lower) (Figure 2b) than control scars in the ITT population at month 9 (ITT: P = 0.0238; PP: P = 0.0521) (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess result robustness. Using the last observation carried forward approach to account for missing data points, aCT1-treated incisions showed a significantly improved VSS at month 9 compared with control-treated incisions (ITT: P = 0.0056; PP: P = 0.0260). Because the 9-month VSS data showed a non-Gaussian distribution (P < 0.0001), nonparametric analyses were performed. These analyses similarly showed a significant improvement in mean VSS score at 9 months with aCT1 treatment (P = 0.0045, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test; P = 0.0046, Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Figure 2. Evaluation of aCT1-treated and control scars over 9 months.

(a) Representative images of paired aCT1-treated and standard-of-care control laparoscopic scars from a participant at the beginning (i.e., at surgery) and at the end (i.e., month 9) of the study. Locations of incisions are left hypochondrial and right hypochondrial. (b) Percentage difference between treated and control scars (intent-to-treat population) over 9 months after laparoscopic surgery using the investigator-assessed Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) and the subcategories from which the summed VSS score is derived: scar pigmentation (orange dashed line), scar pliability relative to surrounding skin (purple dashed line), scar height above the surface of the surrounding skin (green dashed line), and scar vascularity or redness (red dashed line). Treated and control scars show no statistical difference in appearance 1 month after surgery. However, treated scars show progressive improvement relative to control over subsequent months, culminating in a 47% relative improvement in appearance at month 9.

Table 2.

Summary of Vancouver Scar Scoring Scale over the study

| aCTI + SOC ITT | SOC ITT | aCTI + SOC PP | SOC PP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 2 | n = 73 | n = 56 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.0 (3.5) | 5.4 (3.9) | 4.5 (3.3) | 5.0 (3.6) | ||

| Range | 0–12 | 0–13 | 0–12 | 0–13 | ||

| 95 % CI | −0.9 to 0.3 | — | −1.1 to 0.3 | — | ||

| P-value | 0.37 | — | 0.25 | — | ||

| Month 1 | n = 78 | n = 67 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (3.1) | 3.7 (3.4) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.4 (3.1) | ||

| Range | 0–10 | 0–11 | 0–10 | 0–11 | ||

| 95 % CI | −0.7 to 0.5 | — | −0.6 to 0.7 | — | ||

| P-value | 0.80 | — | 0.91 | — | ||

| Month 3 | n = 72 | n = 61 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.6) | 3.1 (3.2) | 2.3 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.9) | ||

| Range | 0–8 | 0–10 | 0–7 | 0–9 | ||

| 95 % CI | −1.0 to 0.2 | — | −1.1 to 0.3 | — | ||

| P-value | 0.19 | — | 0.25 | — | ||

| Month 6 | (n = 68) | (n = 60) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.7) | 1.9 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.6) | ||

| Range | 0–8 | 0–10 | 0–8 | 0–10 | ||

| 95 % CI | −1.0 to 0.3 | — | −0.9 to 0.5 | — | ||

| P-value | 0.29 | — | 0.55 | — | ||

| Month 9 | n = 70 | n = 68 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.7) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.7) | ||

| Range | 0–7 | 0–5 | 0–7 | 0–5 | ||

| 95 % CI | −1.3 to −0.1 | — | −1.3 to 0.01 | — | ||

| P-value | 0.02 | — | 0.05 | — |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ITT, intent to treat; PP, per protocol; SD, standard deviation; SOC, standard of care.

The VSS consists of the sum of four equally weighted subcategories: scar height (a visual index of scar hypertrophy), pigmentation, vascularity, and pliability (scar suppleness). Subcategory analyses indicated statistically significant improvement in scar pigmentation (P = 0.0076) and pliability (P = 0.033) at 9 months in incisions treated with aCT1 (see Supplementary Table S1 online).

Participant sex, body mass index (BMI), and incision location were significant factors affecting mean VSS score. Mean VSS score at month 9 was significantly (P = 0.0058) lower in men than in women. At month 9 participants with a BMI of 20–25 kg/m2 had significantly lower (P = 0.0075) mean VSS scores compared with those with BMIs less than 20 kg/m2 and greater than 25 kg/m2. Incisions located at the supra pubic region had the lowest mean VSS score (0.2, standard deviation [SD] = 0.41) and those located at the umbilical region had the highest mean VSS score (1.4, SD = 2.12) at the end of the study. Although incision location significantly affected mean VSS at 9 months (P = 0.0246), incision location was not significantly biased to either treatment group (Table 1). When both treatment and baseline incision size were considered, factor analyses showed a significant effect on scarring outcome (ITT: P = 0.0051; PP: P = 0.0083). Critically, there was no significant variation in the mean baseline incision size between the treated or control groups (ITT: P = 0.6985; PP: P = 0.5495).

Efficacy analyses involving incision evaluation at earlier time points did not show a significant difference in VSS scores between aCT1-treated or control incisions (Table 2). At 1 month, the appearances of treated and control incisions were judged to be near identical on the VSS metric. At months 3 and 6, mean VSS scores for aCT1-treated incisions were 12.9% and 16.7% lower, respectively, over control-treated incisions (Figure 2 and Table 2). Overall, aCT1-treated incisions showed statistically significant better (lower) VSS scores compared with controls (ITT: P = 0.0017; PP: P = 0.0038).

Secondary efficacy analyses: Global Assessment Score and the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale

Secondary efficacy analyses included using the Global Assessment Score (GAS) and the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) to visually assess scarring outcome. The mean GAS score was significantly improved in aCT1-treated incisions (P < 0.05) compared with control incisions at all time points in both the ITT and PP populations, except at week 2 in the PP population and at month 1 in both ITT and PP analyses (Table 3). Although aCT1-treated incisions showed lower mean scores compared with control scars at week 2 and at months 3, 6, and 9 by observer (assessing investigator), patient POSAS assessment at week 2 and at months 1, 3, 6, and 9 did not show statistically significant differences (Table 3). Sensitivity analysis showed a significant improvement in scarring outcome with aCT1 treatment only at month 9 as assessed by both investigator GAS (investigator, ITT and PP: P < 0.001) and POSAS (patient, ITT: P = 0.0458; PP: P = 0.0009 and observer, ITT: P = 0.0069; PP: P = 0.0019).

Table 3.

Summary of GAS and POSAS scores over the 9-month study

| aCTI + SOC ITT | SOC ITT | P-Value ITT | aCTI+SOC PP | SOC PP | P-Value PP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | |||

| Week 2 | N = 73 | N = 56 | ||||

| Investigator (GAS) | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.3 (2.8) | 0.01 | 6.8 (2.3) | 6.6 (2.5) | 0.06 |

| POSAS–Observer | 15.2 (10.8) | 15.9 (11.5) | 0.38 | 13.3 (9.3) | 14.1 (10.1) | 0.31 |

| POSAS–Patient | 14.6 (9.3) | 15.1 (10.0) | 0.59 | 12.9 (8.0) | 13.5 (9.0) | 0.45 |

| Month 1 | N = 78 | N = 67 | ||||

| Investigator (GAS) | 7.5 (2.1) | 7.4 (2.3) | 0.35 | 7.7 (2.0) | 7.7 (2.1) | 0.78 |

| POSAS–Observer | 12.4 (9.5) | 12.4 (10.1) | 0.98 | 11.3 (8.5) | 11.0 (8.8) | 0.70 |

| POSAS–Patient | 11.5 (7.7) | 11.6 (8.0) | 0.92 | 10.7 (6.8) | 10.6 (6.9) | 0.92 |

| Month 3 | N = 72 | N = 61 | ||||

| Investigator (GAS) | 8.7 (1.8) | 8.3 (2.2) | <0.001 | 9.0 (1.6) | 8.8 (1.9) | 0.02 |

| POSAS–Observer | 10.8 (7.5) | 11.5 (8.8) | 0.39 | 9.5 (6.1) | 9.9 (7.3) | 0.57 |

| POSAS–Patient | 10.1 (5.7) | 10.8 (6.9) | 0.39 | 9.2 (4.7) | 9.7 (5.7) | 0.47 |

| Month 6 | N = 68 | N = 60 | ||||

| Investigator (GAS) | 9.4 (0.9) | 8.9 (1.6) | <0.001 | 9.5 (0.9) | 9.2 (1.5) | <0.01 |

| POSAS–Observer | 8.6 (4.5) | 9.6 (6.2) | 0.25 | 8.0 (4.1) | 8.6 (5.4) | 0.47 |

| POSAS–Patient | 8.5 (3.4) | 9.6 (5.3) | 0.16 | 8.0 (3.1) | 8.9 (4.6) | 0.22 |

| Month 9 | N = 70 | N = 68 | ||||

| Investigator (GAS) | 9.9 (0.3) | 9.5 (0.8) | <0.001 | 9.9 (0.3) | 9.6 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| POSAS–Observer | 6.0 (1.7) | 7.3 (3.1) | 0.06 | 6.0 (1.7) | 7.1 (2.9) | 0.12 |

| POSAS–Patient | 6.6 (1.2) | 7.7 (2.4) | 0.11 | 6.6 (1.2) | 7.6 (2.3) | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: GAS, Global Assessment Scale; ITT, intent to treat; POSAS, Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale; PP, per protocol; SD, standard deviation; SOC, standard of care.

The POSAS visual analog score consists of the summed scores from five subcategories of scar properties in the observer applied assessment (scar vascularization, pigmentation, thickness [similar to scar height/hypertrophy in the VSS], surface roughness, and mechanical pliability) and six subcategories in the patient-assessed variables (scar pain, itchiness, color, stiffness, thickness, and surface area/irregularity). In subcategory analyses, both observers and patients reported a statistically significant improvement in scar thickness (observers, ITT: P = 0.0234; patients, ITT: P = 0.0213) and pliability (observers, ITT: P = 0.0333; patients, ITT: P = 0.00449) at month 9 with aCT1 treatment. Subcategory means and SDs for VSS and POSAS are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online. No statistically significant variance in subcategory means was evident within any visual analog scale at the 1-month time point. Collectively, subcategory data indicated that the pigmentation, thickness, surface roughness, and mechanical suppleness of the scar were variables that likely most contributed to perceived improvement in scarring associated with aCT1 treatment at month 9.

In addition to on-site evaluations, exploratory efficacy analyses were conducted by clinically qualified independent and blinded central examiners using incision photographs. No statistical difference in scar appearance was discriminated at the 1-month time point (ITT: P = 0.5578, PP: P = 0.7506; Wilcoxon signed rank test). However, in accordance with on-site analyses, independent examiners reported that mean GAS showed statistical improvement (ITT: P = 0.0009; PP: P = 0.0018; Wilcoxon signed rank test) in overall scar appearance of aCT1-treated versus control incisions at month 9. Incision healing rates (as assessed by investigator-reported wound closure; 100% re-epithelialization) were comparable between the two treatment groups in both ITT and PP populations.

Safety analyses

Safety analyses were conducted on all participants who received at least one treatment dose (n = 92). This included a participant who received treatment but withdrew consent before post-baseline efficacy assessment. A total of 43 adverse events (AEs) were reported in 16 of 92 (17.4%) participants. A total of 41 incision site AEs (aCT1 = 23[56.1%]); control 18 = [43.9%]) were reported and included infection and secondary complications (e.g., edema, erythema, wound secretion, and pain). All AEs (97.7%) were considered mild, with the exception of one AE (2.3%) of cough that was considered moderate in severity (Table 4). Wound infection was observed in two participants (aCT1 = 1, control = 1) and was not statistically related to treatment. The most common AE was incision site pain, occurring in eight (8.7%) incisions receiving aCT1 and six control incisions (6.5%). One AE (incision site infection) was considered possibly related to the study treatment; it was mild in severity, and the patient recovered. The remaining AEs were reported as unlikely related or not related to treatment. No participants withdrew or discontinued study treatment because of an AE. Immunologic testing using a validated ELISA (WuXi Apptec, Philadelphia, PA) showed no detection of aCT1 antibodies in participant serum.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events by MedDRA system organ class and preferred safety population

| Overall (N = 92) | |

|---|---|

| Patients with at [east one AE, n (%)1 | 16 (17) |

| Patients reporting one AE | 4 (25) |

| Patients reporting more than one AE | 12 (75) |

| AEs by severity, n (%)2 | |

| Mild | 42 (98) |

| Moderate | 1 (2) |

| Severe | 0 (0) |

| Type of AE | Overall | aCT1 + SOC | SOC | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n | n | n | ||

| Incision site infection | 2 (2) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Incision site pain | 8 (9) | 14 | 8 | 6 | 0.79 |

| Incision site edema | 6 (7) | 11 | 6 | 5 | 0.76 |

| Incision site complication3 | 5 (5) | 10 | 5 | 5 | 1.00 |

| Incision site erythema | 1 (1) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Incision site hematoma | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| Wound secretion | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 | — |

| Cough | 1 (1) | 1 | — | — | — |

| Dyspnea | 1 (1) | 1 | — | — | — |

| Total AEs in 16 patients | 43 | ||||

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; SOC, standard of care.

Percentages were calculated by taking respective column header group count as denominator.

Percentages were calculated by taking count of total AEs in 16 patients in corresponding treatment group as denominator.

Incision site complication included reports of a combination of inflammatory symptoms (e.g., inflammation, redness) categorized as incision site complication per investigator discretion.

DISCUSSION

This proof-of-concept study supports the clinical potential of targeting Cx43 in improving the scarring outcome of surgical incisions. The within-participant control design of this trial provides a robust test of efficacy, enabling direct comparison of treatment and control incisions while accounting for intrinsic genetic and environmental factors that may affect wound healing and subsequent scar formation. The incorporation of the Cx43 mimetic peptide aCT1 in acute (within the first 24 hours) SOC treatment of laparoscopic surgical incisions significantly improved scarring, as confirmed in both parametric and nonparametric data analyses, at 9 months after surgery.

An improvement of visual analog scores of 10–15% over control treatment scores has been considered clinically meaningful (Ferguson et al., 2009). aCT1-treated incisions showed a 13% improvement over control at 3 months, 17% improvement at 6 months, and 47% improvement at 9 months, validating aCT1’s clinical potential. Blinded incision analyses at the 1-month time point showed little difference in scar appearance between aCT1-treated and control incisions. These data suggest that the long-term improved scarring outcome associated with aCT1 treatment cannot be predicted by early visual analyses of incisions. Molecular and histological analyses of tissue biopsy samples will likely provide insight into the mechanisms underlying improved scarring outcome associated with acute aCT1 treatment. Early (at the time of wounding) therapeutic intervention may alter the initial and subsequent wound microenvironment, serving to reroute the scarring response, resulting in altered inflammatory responses, altered myofibroblast numbers and kinetics, reduced collagen deposition, and cytoskeleton organization that more closely matches unwounded skin. Abnormal deposition and reorganization of collagen is a critical contributing factor in scarring (Xue and Jackson, 2015). Preliminary analyses of tissue biopsy samples from Phase 1 aCT1 dose-optimization studies suggest that although biopsy scars show marginal differences in superficial appearance at 29 days after injury, granulation tissue in the basal part of the dermis, deep within healed aCT1-treated wounds, shows patterns of collagen order, density, and maturity that differ significantly from paired placebo control wounds (R. Gourdie, personal communication). These changes in the organization of basal granulation tissue in aCT1-treated wounds would likely not be observable at the scar surface at early time points but may underlie the improved scarring outcome that becomes visually discernable at later time points.

Improvement in scar appearance in aCT1-treated incisions was consistent across visual analog scales, including the VSS, GAS, and POSAS scales, although only statistically significant in ITT analyses. Patient assessment using the POSAS indicated similar trends to those reported by investigators; however, these were not statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses using the last observation carried forward approach to account for missing data supported the conclusions reached and showed the robustness of these conclusions. Mathematical extrapolation of our data shows that the differences between aCT1 peptide and control incisions will widen with time and therefore provide a proportional advantage in POSAS. Indeed, the aCT1-induced difference in scarring would be better detected at 12 months. Future clinical trials will involve longer end-point evaluation for primary efficacy measures and additional control arms.

Some notable insights on factors potentially mediating treatment-associated improvements in scar appearance, as perceived by investigators and patients, came from the subcategories used to generate the overall scores for the visual analog scales. These data indicated that scar vascularity or redness was likely not a major factor associated with aCT1-mediated improved scarring outcome. Subcategory variables that appeared consistently affected by treatment in both the VSS and POSAS assessments were the thickness or height that the scar was raised above the surface of surrounding skin and the mechanical pliability or stiffness of the scar relative to surrounding skin. These results fit with preclinical wound-healing studies in which biomechanical analyses at 3 months after excisional skin wounding showed that healed skin from wounds treated with aCT1 showed significantly improved mechanical properties (stress and strain measurements) over vehicle controls (Ghatnekar et al., 2009). These studies further recapitulated healing trends seen in this study, in which biomechanical analyses of aCT1-treated and control skin at earlier time points (1 month) did not show a significant difference.

A patient’s personal belief about the severity of his/her injury has been shown to have a greater influence on quality of life than the actual injury severity (Kennedy et al., 2010; Schut et al., 2014). As such, patient-defined outcomes are critical in evaluating clinical significance. This being recognized, it is not uncommon for a patient’s opinion of the severity of scar physical characteristics to differ from clinical opinion (Hoogewerf et al., 2014; Nicholas et al., 2012). Scar itchiness and scar thickness have been reported as significant factors influencing patient opinion in terms of scarring outcome (Draaijers et al., 2004). In agreement with observer analyses, the subcategory variables that appeared consistently affected by aCT1 treatment in the patient POSAS assessments were scar thickness and the mechanical pliability. Scar thickness is an important visual feature of a scar, and this outcome may translate to significant clinical relevance in trials examining the therapeutic potential of aCT1 in the treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scarring, where scar thickness is a pathology-defining characteristic. Our results highlight the importance of statistically evaluating the subcategories associated with each outcome measure. Additional investigation into the importance of these subcategories (pain, itchiness, color, stiffness, thickness, area/irregularity) and incorporating quality of life assessment would be of benefit in terms of interpreting results in future clinical trials examining scarring outcome.

Topical aCT1 treatment was well tolerated, and the AE profile was consistent with Phase 1 and preclinical studies (Ghatnekar et al., 2009). Incision pain and edema are anticipated because of the nature of the surgery. Wound infections (2%) were observed early in the study, but there was no statistical difference in infection incidence between treatment and control groups. Remaining AEs were mild, with the exception of an incidence of cough, and were considered not related to the study drug.

Pathologic scars result from perturbations in the normal cutaneous wound healing process, where the immune system plays a key role in maintaining a chronic inflammatory activated state in hypertrophic scar tissue (Gauglitz et al., 2011; Wulff et al., 2012). In porcine and murine wound healing models, aCT1 shortened and reduced the amplitude of the initial inflammatory phase of wound healing, reduced wound gape and edema, accelerated the rate of wound closure, prompted decreases in the area of scar granulation tissue, and promoted restoration of dermal histoarchitecture and mechanical strength (Ghatnekar et al., 2009; Rhett et al., 2008). At the molecular level, aCT1 selectively inhibits interaction between Cx43 and the second PDZ domain of ZO-1, releasing Cx43 hemichannels from the perinexus, where they are then sequestered into gap junction aggregates (Rhett et al., 2011). This sequestration causes a reduced membrane density (and hence activity) of hemichannels, concomitant with increases in the extent and function of gap junctions.

Hemichannels have key roles in providing a paracrine route for intercellular communication and are important determinants of various aspects of the wound healing responses, including inflammation, edema, fibrosis, and intercellular propagation of injury (Chi et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2012; Rhett et al., 2014). Animal model studies have also shown that Cx43 hemichannel blockade reduced infarct size after myocardial infarction (Hawat et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013) and decreased glial scarring in both ischemic stroke (Davidson et al., 2015) and spinal cord injury models (Umebayashi et al., 2014). In the context of skin healing and hypertrophic scarring or keloid formation, modulation of Cx43 expression levels has been shown to control the balance between fibroblast proliferation and apoptosis, as well as extracellular matrix deposition (Lu et al., 2007).

We hypothesize that aCT1’s coordinated reduction in Cx43 hemichannel activity and stabilization of Cx43 gap junction aggregates mediates inflammatory responses and mitigates the cellular and molecular processes involved in fibrosis, hypertrophy, and hypergranulation that are responsible for scar formation during wound repair. Most currently applied clinical therapies are largely nontargeted approaches to pathway-specific processes. In addition to tempering excessive/harmful inflammatory responses via reductions in hemichannel activity, preliminary analyses of epidermal and dermal granulation tissue markers in skin biopsy samples suggests that aCT1 has roles in mediating fibroblast motility and collagen deposition within basal granulation tissue deep below the epidermis. Therefore, although existing treatments remain symptomatic, empirical, and unpredictable, aCT1 treatment is prophylactic and shows benefit in the long-term improvement of scarring, thus representing a pharmaceutical approach to scar improvement.

An aCT1 topical formulation presents several advantages in terms of clinician ease of use and patient comfort compared with other options such as silicone sheets and corticosteroid injections. Silicone gel sheeting, a recommended first-line therapy for scar management (Chernoff et al., 2007) that is relatively inexpensive, readily available, and noninvasive, requires extended skin contact for 12–24 hours daily and involves repetitive washing and reapplication protocols. Therefore, despite showing clinical efficacy, patient compliance remains an issue (Maher et al., 2012). Corticosteroid injections have been used to soften and shrink existing keloid scars (Berman and Bieley, 1996) but are associated with little to no efficacy in the treatment of hypertrophic and normal scars, as well as with adverse effects including skin atrophy, depigmentation, and telangiectasias. Renovo (Manchester, United Kingdom) has evaluated injectable TGF-β3 (avotermin) for scar minimization. However, Phase 3 trials indicated failure to meet study endpoints (Ferguson et al., 2009; Zielins et al., 2014). Topical application of aCT1 offers a straightforward, limited-treatment, office-based regimen that does not depend on patient compliance. Further, topical aCT1 treatment has proven safe and efficacious in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers and venous leg ulcers of varying size: it halved the healing time of both pathologic wound types (Ghatnekar et al., 2015; Grek et al., 2015). Further clinical analyses need to be conducted to evaluate aCT1 efficacy in scar mitigation for additional wound types and sizes.

Limitations of the current study include a gender gap, possibly because of the fact that more women were eligible and available for recruitment. In addition, given that statistically significant difference in scar reduction was not observable between treatment groups at early time points, a longer duration of assessment of scar reduction may yield more significant results. Future controlled clinical trials will involve larger, more ethnically diverse and sex-diverse patient populations, as well as larger wound sizes and longer study durations.

This proof-of-concept clinical study supports a role for Cx43 as a regulator in wound healing and scarring and provides evidence of effectiveness and safety of a topically applied Cx43-based therapeutic in improving scar appearance of laparoscopic surgical incisions when used in association with SOC protocols. Given the ease of application and limited application protocol, topically applied aCT1 offers significant potential as a treatment in reducing scarring after surgical procedures. Further investigation will involve mechanistic studies evaluating quantitative collagen structure analyses on aCT1-treated scar tissue and evaluation of aCT1 effects on fibroblast migration, as well as clinical investigation in the treatment of hypertrophic scarring and keloid formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective, randomized, observer-blinded, within-participant control, multicenter study at seven centers in India to assess the efficacy and safety of aCT1 in reducing scar formation in surgical incisional wounds after laparoscopic surgery. The study protocol was approved by all institution ethics committees, was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines and was granted regulatory clearance/approval by the Drug Controller General of India (Clinical Trials Registry India: CTRI/2011/09/002004). The study protocol was registered and published before the date of first enrollment and therefore before any statistical analyses were initiated. Participants were notified of potential risks and benefits, were given the option to withdraw at any time, and signed informed consent forms before enrollment.

Eligible men and women, 18 years or older, undergoing laparoscopic surgery procedures involving at least two 10-mm or greater full-thickness surgical incisions, were recruited. Principal exclusion criteria (see Supplementary Table S3 online) included history of skin irritation, infections, keloids, collagen vascular diseases, and medical conditions/medications that may affect healing outcome.

Study protocol

Randomization, blinding, and intervention

After confirmation of eligibility, participants were registered in an online database, and treatment allocation was made preoperatively. Using the Interactive Web Response System, two bilateral laparoscopic incision sites (≥10 mm) on the same participant at comparable locations were chosen to be randomized 1:1 to receive 100 μmol/L (0.036%) aCT1 topical formulation plus SOC or SOC alone. An unblinded coordinator designated by the investigator received the assigned treatment through the Interactive Web Response System. Randomization lists were prepared centrally using a validated computer program (SAS 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Trial sponsor, trial monitors, statisticians, and the observer who performed assessments were blinded to treatment assignments.

The intervention (aCT1 gel formulation) is manufactured as a clear topical gel formulation (1.25% hydroxyethyl cellulose) containing aCT1 (100 μmol/L). Preclinical studies validated the efficacy and safety of a 100 μmol/L aCT1 concentration (Ghatnekar et al., 2009). aCT1 dosing strategies were further optimized in a Phase 1, double-blind, single-center controlled study designed to evaluate the safety and tolerability of 20-, 50-, 100-, and 200 μmol/L concentrations of aCT1 versus vehicle control in 48 healthy participants after punch biopsy. This study recapitulated preclinical studies that indicated optimal safety and therapeutic efficacy (in terms of accelerating wound closure and reducing scarring without treatment-related AEs) at 100 μmol/L of aCT1 concentration. The treatment regimen, at the time of incision closure and 24 hours later, was based on ongoing insight into the mode of action of aCT1 (Ghatnekar et al., 2009; Hunter et al., 2005; O’Quinn et al., 2011; Rhett et al., 2011). Trial site-specific research-trained nurses not acting as investigators administered two applications of aCT1 to incisions in the treatment group: the first at the time of surgery (application subcutaneously before suturing and then cutaneously over the entire incision site after suturing) and the second 24 hours later (on suture surface). aCT1 gel was dispensed directly from 2-ml glass vials in amounts sufficient to evenly cover the entire surgical incision surface. No guidance was given in the protocol as to the precise quantity of aCT1 for application.

Both treatment (aCT1 treated) and control incisions (SOC alone) received the same SOC. SOC protocols involved moisture-retention protocols involving application of sterile saline-soaked gauze covered with occlusive dressing (Tegaderm, 3M, St. Paul, MN) after suturing. Dressings remained undisturbed for 24 hours, at which point treatment was reapplied and dressings were changed, unless the investigator assessed exudate, leakage, inflammation, or suspected infection and suggested additional intervention. Ongoing SOC protocols involved maintenance of wound moisture and occlusive dressing for at least 1 month after surgery.

Study endpoints

Incision sites were assessed a total of 14 times over the 9 months of the study and involved evaluation of scar appearance, incision site closure, and safety. The primary efficacy variable was reduction in scarring from week 2 to month 9 using the VSS. The VSS is a widely accepted clinical visual analog score of scar appearance, consisting of the sum of scores from four equally weighted subcategories, where each variable has three to six possible scores and summed scores range from 0 (normal skin) to 13 (Bae and Bae, 2014; Lumenta et al., 2014). Although originally validated for burn scars, studies confirm the validity of the VSS scale to objectively evaluate postsurgical scars (Truong et al., 2005, 2007).

Secondary efficacy endpoints included reduction in scarring from week 2 to months 1, 3, 6, and 9 assessed using the VSS, GAS, and the POSAS and assessment of healing rate and incidence of treatment-related AEs. The GAS score involved blinded investigator (both by an at-site clinically qualified investigator and independently by another qualified investigator centrally) incision and scar assessment, using an analog scale of 1 (worse) to 10 (most improved). The POSAS includes both a patient and investigator evaluation and has been reported to have good internal consistency, interobserver reliability, and correlation with the VSS in the assessment of linear surgical scars (Draaijers et al., 2004; Truong et al., 2007; van de Kar et al., 2005). POSAS variables are each evaluated on a scale from 1 to 10, where summed scores range from 5 (normal skin) to 50 for the observer assessment and from 6 (normal skin) to 60 for the patient assessment (Draaijers et al., 2004).

Safety was determined through measurement of vitals, laboratory testing, and AE reporting. Safety variables were incidence of treatment of emergent AEs and infection. AEs were coded using Med-DRA, version 15.1. Laboratory assessments, immunogenicity testing for anti-aCT1 antibodies, and vitals measurements were performed at initial and final study visits.

Statistical analysis

The enrolled sample size was calculated with reference to the primary endpoint (comparing efficacy in improving scar appearance after laparoscopic surgery per the VSS at month 9), assuming a 22% difference in favor of incisions treated with aCT1. A total of least 80 incisions per treatment group was calculated to provide at least 80% power, based on an SD of 46%, and a significance of 95% (two sided). Adjusting for a 15% anticipated dropout rate, a sample size of 92 scars per treatment arm was estimated for primary efficacy analyses. All statistical tests were carried out as two sided on a 5% level of significance. Primary efficacy analyses were conducted on both ITT and PP populations using linear mixed model with repeated measure at a 95% confidence interval with treatment, visit, and their interaction as factors and treatment center, age, sex, incision location, and BMI as covariants, using the PROC MIXED procedure of SAS software. To check the robustness of the results drawn from the primary outcome, sensitivity analysis were performed using analysis of covariance with treatment as factors and treatment center, age, sex, incision location, and BMI as covariates using PROC MIXED procedure of SAS software, using the last observation carried forward approach, where for missing data points the last available observation was carried forward. Investigator wound assessment using the GAS was assessed and compared at each time point between groups using the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. For the exploratory endpoint, the central investigator evaluated wound closure and scarring outcome at each time point using the GAS through computerized planimetry of digital photographs of incisions using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

The Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test was used for data in which the normality assumption was tested by Shapiro-Wilk and Q-Q plots. Wound closure and incidence of infection were compared using McNemar test. For comparing incidence of AEs, a two-sample test of proportions for which the statistic is distributed as standard normal was used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the investigators and patients who participated in the study, as well as the medical staff involved in patient care. In particular we would like to thank Prashant Vithalrao Rahate (Rahate Surgical Hospital and ICU, Maharashra, India), G. Venkat Rao (Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Andhra Pradesh, India), Jayashree Shankarrao Todkar (Poona Hospital and Research Centre, Mahatashtra, India), and Nirmal Chopra (Chopra Super-speciality Hospital, Uttar Pradesh, India). We would also like to acknowledge Stefanie Cuebas, who contributed to figure design, and Jayashri Krishnan who served as a medical monitor.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Gautam Ghatnekar and Robert Gourdie are co-inventors of aCT1 and cofounded FirstString Research. FirstString Research has an exclusive, worldwide license for all fields of use for aCT1. Ghatnekar is currently president and CEO of FirstString and has company stock options. Grek is an employee of FirstString Research and has company stock options. Gourdie is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of FirstString Research and has stock options issued by the company. None of the clinical investigators involved in the study have any patent ownership, royalties, or financial gain associated with the successful clinical development of this technology.

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- BMI

body mass index

- GAS

Global Assessment Scale

- ITT

intent to treat

- POSAS

Patient Observer Scar Assessment Scale

- PP

per protocol

- SD

standard deviation

- SOC

standard of care

- VSS

Vancouver Scar Scale

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.jidonline.org, and at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.006.

References

- Bae SH, Bae YC. Analysis of frequency of use of different scar assessment scales based on the scar condition and treatment method. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41:111–5. doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Urso-Baiarda F, Linge C, Grobbelaar A. Cutaneous scarring: a clinical review. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009:625376. doi: 10.1155/2009/625376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat A, Bock O, Mrowietz U, Ollier WE, Ferguson MW. Genetic susceptibility to keloid disease and hypertrophic scarring: transforming growth factor beta1 common polymorphisms and plasma levels. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:535–43. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041536.02524.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman B, Bieley HC. Adjunct therapies to surgical management of keloids. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:126–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush J, Duncan JA, Bond JS, Durani P, So K, Mason T, et al. Scar-improving efficacy of avotermin administered into the wound margins of skin incisions as evaluated by a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010a;126:1604–15. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef8e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush J, So K, Mason T, Occleston NL, O’Kane S, Ferguson MW. Therapies with emerging evidence of efficacy: avotermin for the improvement of scarring. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010b;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/690613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush JA, McGrouther DA, Young VL, Herndon DN, Longaker MT, Mustoe TA, et al. Recommendations on clinical proof of efficacy for potential scar prevention and reduction therapies. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(Suppl. 1):s32–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder BW, Matthew Rhett J, Bainbridge H, Fann SA, Gourdie RG, Yost MJ. Inhibition of connexin 43 hemichannel-mediated ATP release attenuates early inflammation during the foreign body response. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1752–62. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff WG, Cramer H, Su-Huang S. The efficacy of topical silicone gel elastomers in the treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloid scars, and post-laser exfoliation erythema. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:495–500. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi Y, Gao K, Li K, Nakajima S, Kira S, Takeda M, et al. Purinergic control of AMPK activation by ATP released through connexin 43 hemichannels – pivotal roles in hemichannel-mediated cell injury. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1487–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.139089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittoria RK, Padi TR. A prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, double blind study of silicone gel in prevention of hypertrophic scar at donor site of skin grafting. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:12–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.110090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churko JM, Kelly JJ, Macdonald A, Lee J, Sampson J, Bai D, et al. The G60S Cx43 mutant enhances keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:612–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2012.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogliati B, Vinken M, Silva TC, Araujo CM, Aloia TP, Chaible LM, et al. Connexin 43 deficiency accelerates skin wound healing and extracellular matrix remodeling in mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;79:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JO, Green CR, Bennet L, Gunn AJ. Battle of the hemichannels—connexins and pannexins in ischemic brain injury. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;45:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Tuinebreijer WE, Middelkoop E, Kreis RW, et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1960–5. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000122207.28773.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MW, Duncan J, Bond J, Bush J, Durani P, So K, et al. Prophylactic administration of avotermin for improvement of skin scarring: three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I/II studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1264–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MW, O’Kane S. Scar-free healing: from embryonic mechanisms to adult therapeutic intervention. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:839–50. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauglitz GG, Korting HC, Pavicic T, Ruzicka T, Jeschke MG. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies. Mol Med. 2011;17:113–25. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatnekar GS, Grek CL, Armstrong DG, Desai SC, Gourdie RG. The effect of a connexin43-based Peptide on the healing of chronic venous leg ulcers: a multicenter, randomized trial. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:289–98. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatnekar GS, O’Quinn MP, Jourdan LJ, Gurjarpadhye AA, Draughn RL, Gourdie RG. Connexin43 carboxyl-terminal peptides reduce scar progenitor and promote regenerative healing following skin wounding. Regen Med. 2009;4:205–23. doi: 10.2217/17460751.4.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grek CL, Prasad GM, Viswanathan V, Armstrong DG, Gourdie RG, Ghatnekar GS. Topical administration of a connexin43-based peptide augments healing of chronic neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers: A multicenter, randomized trial. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:203–12. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawat G, Helie P, Baroudi G. Single intravenous low-dose injections of connexin 43 mimetic peptides protect ischemic heart in vivo against myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:559–66. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogewerf CJ, van Baar ME, Middelkoop E, van Loey NE. Patient reported facial scar assessment: directions for the professional. Burns. 2014;40:347–53. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AW, Barker RJ, Zhu C, Gourdie RG. Zonula occludens-1 alters con-nexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5686–98. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfstrom ML, Smithson E. Cognitive appraisals, coping and quality of life outcomes: a multi-centre study of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:762–9. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorraine C, Wright CS, Martin PE. Connexin43 plays diverse roles in coordinating cell migration and wound closure events. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43:482–8. doi: 10.1042/BST20150034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D, Soleymani S, Madakshire R, Insel PA. ATP released from cardiac fi-broblasts via connexin hemichannels activates profibrotic P2Y2 receptors. FASEB J. 2012;26:2580–91. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-204677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Gao J, Ogawa R, Hyakusoku H. Variations in gap junctional intercellular communication and connexin expression in fibroblasts derived from keloid and hypertrophic scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:844–51. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000255539.99698.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumenta DB, Siepmann E, Kamolz LP. Internet-based survey on current practice for evaluation, prevention, and treatment of scars, hypertrophic scars, and keloids. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:483–91. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher SF, Dorko L, Saliga S. Linear scar reduction using silicone gel sheets in individuals with normal healing. J Wound Care. 2012;21:602, 604–6, 608–9. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.12.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez-Rosado L, Singh D, Rincon-Arano H, Solan JL, Lampe PD. CASK (LIN2) interacts with Cx43 in wounded skin and their coexpression affects cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:695–702. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhi B, Sewal RK, Kaman L, Kadhe G, Mane A. Efficacy and safety of an advanced formula silicone gel for prevention of post-operative scars. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2013;3:157–67. doi: 10.1007/s13555-013-0036-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier K, Nanney LB. Emerging new drugs for scar reduction. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2006;11:39–47. doi: 10.1517/14728214.11.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelkoop E, Monstrey S, Teot L, Vranckx JJ, editors. Scar management practical guidlines. Elsene, Belgium: Maca-Cloetens; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Monstrey S, Middelkoop E, Vranckx JJ, Bassetto F, Ziegler UE, Meaume S, et al. Updated scar management practical guidelines: non-invasive and invasive measures. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:1017–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe TA. Scars and keloids. BMJ. 2004;328:1329–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, Hobbs FD, Ramelet AA, Shakespeare PG, et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560–71. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas RS, Falvey H, Lemonas P, Damodaran G, Ghanem AM, Selim F, et al. Patient-related keloid scar assessment and outcome measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:648–56. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182402c51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien L, Jones DJ. Silicone gel sheeting for preventing and treating hy-pertrophic and keloid scars. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003826. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003826.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll SJ, Becker DL, Davidson JO, Gunn AJ, Nicholson LF, Green CR. The use of connexin-based therapeutic approaches to target inflammatory diseases. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1037:519–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Quinn MP, Palatinus JA, Harris BS, Hewett KW, Gourdie RG. A peptide mimetic of the connexin43 carboxyl terminus reduces gap junction remodeling and induced arrhythmia following ventricular injury. Circ Res. 2011;108:704–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu C, Coutinho P, Frank S, Franke S, Law LY, Martin P, et al. Targeting connexin43 expression accelerates the rate of wound repair. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett JM, Fann SA, Yost MJ. Purinergic signaling in early inflammatory events of the foreign body response: modulating extracellular ATP as an enabling technology for engineered implants and tissues. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2014;20:392–402. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett JM, Ghatnekar GS, Palatinus JA, O’Quinn M, Yost MJ, Gourdie RG. Novel therapies for scar reduction and regenerative healing of skin wounds. Trend Biotechnol. 2008;26:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhett JM, Jourdan J, Gourdie RG. Connexin 43 connexon to gap junction transition is regulated by zonula occludens-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1516–28. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P, Wilson L, Gruen RL, Bickler SW. Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(Suppl. 2):S13–20. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schut C, Felsch A, Zick C, Hinsch KD, Gieler U, Kupfer J. Role of illness representations and coping in patients with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1566–71. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidgwick GP, McGeorge D, Bayat A. A comprehensive evidence-based review on the role of topicals and dressings in the management of skin scarring. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:461–77. doi: 10.1007/s00403-015-1572-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit JM, Bauland CG, Wijnberg DS, Spauwen PH. Pulsed dye laser treatment, a review of indications and outcome based on published trials. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:981–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong PT, Abnousi F, Yong CM, Hayashi A, Runkel JA, Phillips T, et al. Standardized assessment of breast cancer surgical scars integrating the Vancouver Scar Scale, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, and patients’ perspectives. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1291–9. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000181520.87883.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong PT, Lee JC, Soer B, Gaul CA, Olivotto IA. Reliability and validity testing of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale in evaluating linear scars after breast cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:487–94. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000252949.77525.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziotzios C, Profyris C, Sterling J. Cutaneous scarring: pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and scar reduction therapeutics Part II. Strategies to reduce scar formation after dermatologic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umebayashi D, Natsume A, Takeuchi H, Hara M, Nishimura Y, Fukuyama R, et al. Blockade of gap junction hemichannel protects secondary spinal cord injury from activated microglia-mediated glutamate exitoneurotoxicity. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:1967–74. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Kar AL, Corion LU, Smeulders MJ, Draaijers LJ, van der Horst CM, van Zuijlen PP. Reliable and feasible evaluation of linear scars by the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:514–22. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000172982.43599.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, De Vuyst E, Ponsaerts R, Boengler K, Palacios-Prado N, Wauman J, et al. Selective inhibition of Cx43 hemichannels by Gap19 and its impact on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:309. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0309-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff BC, Parent AE, Meleski MA, DiPietro LA, Schrementi ME, Wilgus TA. Mast cells contribute to scar formation during fetal wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:458–65. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M, Jackson CJ. Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring. Adv Wound Care. 2015;4:119–36. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielins ER, Atashroo DA, Maan ZN, Duscher D, Walmsley GG, Hu M, et al. Wound healing: an update. Regen Med. 2014;9:817–30. doi: 10.2217/rme.14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.