Abstract

Purpose of Review

Pervasive disparities in T2DM among minority adults are well-documented, and scholars have recently focused on the role of social determinants of health (SDOH) in disparities. Yet, no research has summarized what is known about racial/ethnic disparities in youth-onset T2DM. This review summarizes the current literature on racial/ethnic disparities in youth-onset T2DM, discusses SDOH that are common among youth with T2DM, and introduces a conceptual model on the possible role of SDOH in youth-onset T2DM disparities.

Recent Findings

Minority youth have disparities in the onset of T2DM, quality of life, and family burden. Low family income and parental education and high youth stress are common negative SDOH among families of youth with T2DM. No studies have examined the role of SDOH in racial/ethnic disparities in youth-onset T2DM.

Summary

Future research should examine whether SDOH contribute to disparities in T2DM prevalence and psychosocial outcomes among minority youth.

Keywords: Race/ethnicity, Type 2 diabetes, Disparities, Social determinants of health, Youth, Pediatric

Introduction

There has been a striking increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in childhood related to the global epidemic of childhood obesity [1]. T2DM has accounted for a substantial proportion of adolescents with diabetes only recently; prior to 15 years ago, T2DMaccounted for approximately 3% of cases of new-onset diabetes in adolescents, while currently approximately 45% of adolescents who are diagnosed with diabetes have T2DM [2]. Given T2DM has only recently become more frequent in youth, the literature addressing youth-onset T2DM is relatively scarce compared to research on T2DM in adulthood.

It is known that compared to adults with T2DM, youth show more rapidly progressing signs of kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes-related eye disease, as well as poor glycemic control [3, 4]. It is also known that most youth who develop T2DM are obese, have a family history of T2DM, and are from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds [5]. Indeed, the increased rates of T2DM among minority youth are in line with the higher rates of T2DM among minority adults compared to non-minorities.

Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of T2DM in adulthood are well-documented [6, 7]. In addition to disparities in diabetes prevalence, minority adults also have disparities in diabetes complications, glycemic control, and diabetes care [8–10]. Health disparities are usually defined as negative differences in health that are closely linked with social, economic, and environmental disadvantages [11]. Notably, there is increasing focus on the role of social determinants of health (SDOH) as a key cause of disparate health outcomes among minority adults with diabetes [12–14]. Social determinants of health are the conditions in which families live that can adversely influence health, such as low family socioeconomic status or neighborhood poverty.

Given that racial/ethnic minority children and families in the general population also have disproportionate social, economic, and environmental disadvantages [15–17], it is possible that there are pervasive disparities in youth-onset T2DM. Yet, no literature has summarized studies that have examined racial/ethnic differences in youth-onset T2DM outcomes. Such a review can help determine directions for future research on disparities in this population. Further, a summary of research on the SDOH among youth with T2DM can also inform future research that aims to determine their role in T2DM disparities. Identifying social determinants that contribute to disparities has a strong potential for supporting effective interventions to eliminate them.

The purpose of this review is to summarize the existing literature on racial/ethnic disparities in youth-onset T2DM, discuss SDOH that are common among youth with T2DM and their families, and introduce a conceptual model that highlights the possible role of social determinants in youth-onset T2DM to guide future research.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Prevalence, Glycemic Control, and Comorbidities

The prevalence of T2DM is highest among racial/ethnic minority youth, whereby approximately 80% of youth with T2DM are from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds [18]. In the treatment options for type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth (TODAY) study, which had the best characterized cohort of youth with T2DM, 30% of youth were African-American, 40% were Hispanic/Latino, and 6% were American-Indian [3]. Projections further indicate that these racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of T2DMwill persist into the year 2050. Estimates showed the prevalence of T2DM among youth will be the highest among African-Americans and Hispanics at 1.63 and 0.96 per 1000 children, respectively, compared to 0.28 per 1000 children for non-Hispanic whites [19].

Baseline data from the TODAY study and the SEARCH for diabetes in youth studies indicated poorer glycemic control among African-American and Hispanic youth [20•, 21]. In contrast, findings from the TODAY study did not indicate many racial/ethnic differences in T2DM comorbidities or complications among youth [22]. Overall, the higher rate of T2DM and poorer glycemic control in minority youth is particularly troublesome, given that individuals with an onset of T2DM in adolescence may experience complications during early adulthood years that are typically productive [22]. Such an increase in T2DM complications in early adulthood could amplify the significant and costly disparities among minority adults with T2DM [23–25].

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Psychosocial Functioning

Very few studies have focused on psychosocial functioning in youth with T2DM. Initial studies indicate disparities in some areas of psychosocial functioning [26]. African-American youth reports poorer quality of life than non-Hispanic white youth [26]. Another study indicated Hispanic parents have higher burden from their children’s diabetes management [26]. No racial/ethnic differences have been found in depressive symptoms in the TODAY trial or depression screening study conducted by the pediatric diabetes consortium [22, 27•]. Finally, no racial/ethnic differences have been found in binge-eating [22].

SDOH among Children with T2DM

Similar to research with racial/ethnic children in the general population, studies among children with T2DMand their families indicate that a substantial portion have negative SODH. Such social determinants occur at the individual- and family-level. They include low family socioeconomic status, low parental educational attainment, and greater youth life stressors. Data from the TODAY trial was among the first to document the characteristics of youth with T2DMand their families. The findings indicated that approximately 25% of parents’ highest level of education was less than high school, and 40% of families had a yearly family income of $25,000 or less [21]. In the pediatric diabetes consortium clinic registry, 70% of parents of children with T2DM had obtained a high school education or less and 43%had a family income of $25,000 per year or less [18]. Many youth with T2DM also experience major life stressors, such as repeating a grade in school or parental illness. Approximately half of youth with T2DM experience two more life stressors within a 1-year period [28•].

While these initial studies have indicated that some negative SDOH are common among youth with T2DM, research is needed that examines whether they are significant contributors to racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM prevalence, glycemic control, and/or psychosocial functioning. A conceptual model can be useful for guiding further research in this area. A conceptual model may aid in the examination of the role of SDOH in disparities in T2DM among minority youth.

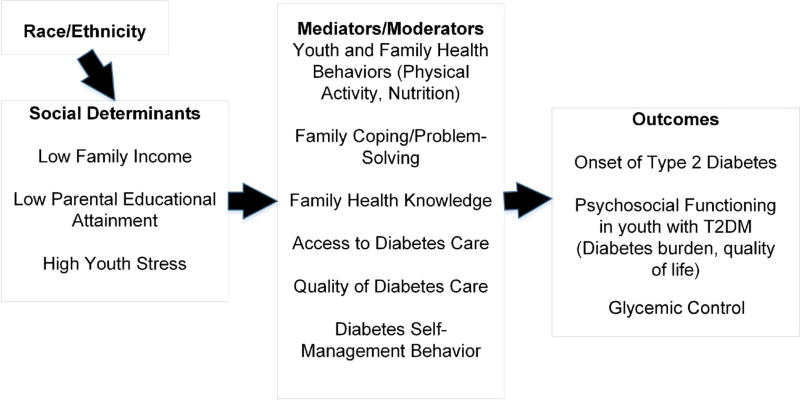

Conceptual Model of SDOH and T2DM Outcomes in Youth

Two conceptual frameworks that address the role of SDOH in the health outcomes of adults were combined to develop a model focused on youth-onset T2DM. The first model, which was set forth by Walker et al., includes a focus on income and stress as social determinants of poor glycemic control [29]. This empirically supported conceptual model indicates that low income leads to worse access to diabetes care and lower quality of care and thereby contributes to poor glycemic control. The model also specifies that high-perceived stress leads to poorer glycemic control by compromising self-care behaviors and increasing the likelihood of receiving poor quality care.

The second model was set forth by Braveman et al., [30] is grounded in the research literature, and focuses on low educational attainment as a SDOH. The model indicates that lower educational attainment among adults leads to health outcomes by contributing to poorer health behaviors, health knowledge, and problem-solving/coping.

In our model illustrated in Fig. 1, we indicate that social determinants of low family income, low levels of parental educational attainment, and higher stress in youth, all of which have been demonstrated to be prevalent in this population, can indirectly contribute to both the onset and course of T2DM and adverse psychosocial outcomes, such as poor quality of life. These social determinants can contribute to diabetes outcomes through their influence on health behaviors, health knowledge, coping/ problem-solving, or health care. Indeed, previous research has demonstrated a higher number of stressors within a 1-year period are associated with impaired psychosocial functioning and lower adherence among adolescents with T2DM [28•].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of social determinants of health and racial/ethnic disparities in T2DM. (Adapted with permission from: Walker RJ et al. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:82; with permission from BioMed Central) [29]

Directions for Future Research

Future research that takes advantage of existing cohorts of individuals with youth-onset diabetes should examine whether there are racial/ethnic disparities in complications or comorbidities in adulthood. Additional research should also explore the occurrence of other SDOH in youth with T2DM, including poor neighborhood characteristics and social support. Further, cross-sectional and longitudinal research is also needed to better understand the relationships between social determinants and the onset and outcomes of T2DMin youth and their families. Such research should also seek to identify the factors that mediate the associations, such as health behavior, psychosocial functioning, or access and quality of health care, as well as biologic factors. Finally, future studies should also explore whether social determinants mediate associations between race/ethnicity and T2DM prevalence, quality of life, and family burden to determine areas that may be fruitful for intervention to help eliminate disparities. For example, if youth stressors mediate associations between race/ethnicity and quality of life among African-American youth, culturally informed interventions to help eliminate disparities in quality of life could focus on stress management strategies.

Conclusions

The number of youth with T2DM has increased only recently to numbers that allow reliable study of racial/ethnic disparities or social determinants in youth-onset T2DM. Accordingly, this review illustrates that relatively few studies have examined racial/ethnic disparities in youth-onset T2DM or SDOH in this population. Among the few studies that have investigated racial/ethnic differences, results indicated disparities in T2DM prevalence among African-American, Hispanic, and American-Indian youth. Disparities were also reported for quality of life among African-American youth and for family burden among Hispanic youth. Further, the few studies that included SDOH were descriptive and reported that many youth with T2DM have an increased number of stressors and are from families with low socioeconomic status. Fruitful next steps for research include linking these areas of research on disparities and social determinants. Future studies should examine whether family socioeconomic status or youth stress plays a role in racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of youth-onset T2DM prevalence, as well as on quality of life and family burden of disease.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (K12 DK097696).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P. The global spread of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2005;146(5):693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Group TS, Zeitler P, Hirst K, Pyle L, Linder B, Copeland K, et al. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2247–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P. Acute and chronic complications of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. Lancet. 2007;369(9575):1823–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman FR. Type 2 diabetes in children and youth. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2005;34(3):659–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2005.04.010. ix–x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ. Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: whites, blacks, hispanics, and asians. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2317–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2001;286(10):1195–200. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hosler AS, Melnik TA. Population-based assessment of diabetes care and self-management among Puerto Rican adults in New York City. Diabetes Educ. 2005;31(3):418–26. doi: 10.1177/0145721705276580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanting LC, Joung IM, Mackenbach JP, Lamberts SW, Bootsma AH. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients: a review. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2280–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris MI. Racial and ethnic differences in health insurance coverage for adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(10):1679–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevention CfDCa. Health disparities and inequalities report. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker RJ, Strom Williams J, Egede LE. Influence of race, ethnicity and social determinants of health on diabetes outcomes. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(4):366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canedo JR, Miller ST, Schlundt D, Fadden MK, Sanderson M. Racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes quality of care: the role of healthcare access and socioeconomic status. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0335-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez G, Wilson-Frederick Wilson SM, Thorpe RJ., Jr Examining place as a social determinant of health: association between diabetes and US geographic region among non-Hispanic whites and a diverse group of Hispanic/Latino men. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(4):319–31. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corcoran J, Nichols-Casebolt A. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of ecological framework for assessment and goal formulation. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2004;21:211–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musu-Gillette L, Robinson J, McFarland J, KewalRamani A, Zhang A, Wilkinson-Flicker S. Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2016 (NCES 2016-007) U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC: 2016. [Retrieved 15 Nov 2016]. http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Logan A. The state of minorities: how are minorities faring in the economy? Center for American Progress. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klingensmith GJ, Connor CG, Ruedy KJ, Beck RW, Kollman C, Haro H, et al. Presentation of youth with type 2 diabetes in the pediatric diabetes consortium. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(4):266–73. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imperatore G, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Case D, Dabelea D, Hamman RF, et al. Projections of type 1 and type 2 diabetes burden in the U.S. population aged <20 years through 2050: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and population growth. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2515–20. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20•.Hood KK, Beavers DP, Yi-Frazier J, Bell R, Dabelea D, McKeown RE, et al. Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(4):498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.011. This paper reports higher family burden among Hispanic families of youth with T2DM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Copeland KC, Zeitler P, Geffner M, Guandalini C, Higgins J, Hirst K, et al. Characteristics of adolescents and youth with recent-onset type 2 diabetes: the TODAY cohort at baseline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):159–67. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tryggestad JB, Willi SM. Complications and comorbidities of T2DM in adolescents: findings from the TODAY clinical trial. J Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29(2):307–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perneger TV, Brancati FL, Whelton PK, Klag MJ. End-stage renal disease attributable to diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):912–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook CB, Erdman DM, Ryan GJ, Greenlund KJ, Giles WH, Gallina DL, et al. The pattern of dyslipidemia among urban African-Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(3):319–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter JS, Pugh JA, Monterrosa A. Non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in minorities in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(3):221–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes ET, Goran MI, Lieu TA, Lustig RH, Prosser LA, Songer TJ, et al. Health-related quality of life in adolescents with or at risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr. 2012;160(6):911–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Silverstein J, Cheng P, Ruedy KJ, Kollman C, Beck RW, Klingensmith GJ, et al. Depressive symptoms in youth with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: results of the pediatric diabetes consortium screening assessment of depression in diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2341–3. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0982. This paper examined racial/ethnic differences in depression, and no significant differences were found. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Walders-Abramson N, Venditti EM, Ievers-Landis CE, Anderson B, El Ghormli L, Geffner M, et al. Relationships among stressful life events and physiological markers, treatment adherence, and psychosocial functioning among youth with type 2 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;165(3):504–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.05.020. This paper reports high numbers of recent stressors among youth with T2DM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, Egede LE. Relationship between social determinants of health and processes and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: validation of a conceptual framework. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-14-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]