Abstract

Background

Ascending aortic dimensions are slightly larger in young competitive athletes compared to sedentary controls, but rarely greater than 40 mm. Whether this finding translates to aortic enlargement in older, former athletes is unknown.

Methods and Results

This cross-sectional study involved a sample of 206 former National Football League (NFL) athletes compared with 759 male subjects from the Dallas Heart Study-2 (DHS) (mean age 57.1 and 53.6 years respectively, p < 0.0001; body surface area of 2.4 and 2.1 m2 respectively, p < 0.0001). Mid-ascending aortic dimensions were obtained from computed tomographic scans performed as part of a NFL screening protocol or as part of the DHS. Compared to a population based control group, former NFL athletes had significantly larger ascending aortic diameters (38±5 vs. 34±4 mm; p<0.0001). A significantly higher proportion of former NFL athletes had an aorta of greater than 40 mm (29.6% versus 8.6%, p<0.0001). After adjusting for age, race, body surface area, systolic blood pressure, history of hypertension, current smoking, diabetes, and lipid profile the former NFL athletes still had significantly larger ascending aortas (p<0.0001). Former NFL athletes were twice as likely to have an aorta greater than 40 mm after adjusting for the same parameters.

Conclusions

Ascending aortic dimensions were significantly larger in a sample of former NFL athletes after adjusting for their size, age, race and cardiac risk factors. Whether this translates to an increased risk is unknown and requires further evaluation.

Keywords: Aorta, Ascending aorta, Exercise, Computed Tomography, National Football League, Dallas Heart Study

The term “athlete’s heart” refers to a constellation of structural, functional and electrical cardiac adaptations that can occur as a result of intensive, regular exercise over a prolonged period of time1, 2. According to the Morganroth theory3, the type and extent of these cardiac adaptations are dependent upon the sport pursued. Endurance training, characterized by prolonged increases in cardiac output, results in four chamber enlargement, eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy, and normal diastolic function. Conversely, strength training, characterized by brief but dramatic increases in afterload, is proposed to result in concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. While this adaptive response has not been consistently shown in strength athletes, American Style Football players have been shown to develop concentric hypertrophy2, 4. Theoretically, these hemodynamic loads would be expected to result in enlargement of the aorta and indeed, alterations in the elastic properties of the aorta have been demonstrated in elite athletes5. While studies have indicated that elite athletes have significantly larger ascending aortic dimensions than the general population5–7, these changes are small and still fall within established limits for the general population8. Very few athletes (1.0–1.8%) have an ascending aorta measuring greater than 40 mm5, 8, 9, an arbitrary cut off used clinically and in practice guidelines to define aortic enlargement. To date, studies have been limited to young, currently active athletes. It is unclear if these changes in aortic dimensions regress, persist, or progress through adulthood. The purpose of this study was to evaluate ascending aortic dimensions in older, former elite athletes, specifically, former National Football League (NFL) athletes and compare them to a similar age and ethnic control group.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study comparing a self-selected sample of former NFL athletes to a presumed non-elite athletic control group from the Dallas Heart Study-2 (DHS). Former NFL athletes were invited to participate in voluntary cardiovascular screening as part of the NFL Players Care Foundation Healthy Body and Mind Screening Program between January 2014 and January 2015 (Canton, OH; Cincinnati, OH; Dallas, TX; Indianapolis, IN; Las Vegas, NV; New York City, NY; Orlando, FL; Phoenix, AZ; Pittsburg, PA). The screening was performed by experienced personnel from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation and the data was de-identified and stored in a secure database with MedStar Sports Medicine. Screening was composed of a cardiovascular history questionnaire which was reviewed by a cardiologist with the player to ensure accuracy of data, basic biometrics (height and weight), four blood pressure readings, lipid profile, and a non-contrast computed tomographic (CT) scan for assessment of coronary calcium burden. Former NFL athletes with a history of coronary disease or those who had underwent a recent CT scan (within one year) were not offered a CT scan; all others were offered the test after being provided a summary of the risks and benefits of the scan. Those individuals with a recent CT scan were excluded to minimize excess radiation and its associated long-term effects as well as the potential duplication of data. A participant flowchart is displayed in the Supplemental Figure 1. The study was approved by the MedStar Health Institutional Review Board and all participants signed written informed consent forms for the study.

The DHS was selected as the control group given the ethnic diversity in that population with a large African American population. The design details of the DHS has been described in detail previously10. Briefly, it is a probability-based population cohort of 3,072 adults from Dallas County approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled between 2000–2002 and there was intentional oversampling of African Americans. The second phase was performed between 2007–2009 and included follow-up visits of 2,485 DHS participants along with 916 spouses of the original cohort. For the present analysis, we pre-specified selection of male, white and black DHS-2 participants at least 40 years of age, and with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 20 kg/m2. The final DHS control population with interpretable CT scans consisted of 759 male participants (Supplemental Figure 2).

CT Imaging

Imaging was performed on a variety of multi-detector CT (MDCT) scanners from different vendors as screening for the former NFL athletes was performed in different locations throughout the country. For DHS participants, MDCT scans were performed on a Toshiba Aquilon (64 slice). All scans were non-contrast, prospectively acquired, electrocardiographically triggered during diastole (75% of the R-R interval), and with slice thickness of 3 mm performed according to current guidelines11. Measurement were made by a licensed imaging physician experienced in cardiac CT. Ascending aortic diameter measurements were measured on axial images at the level of the pulmonary artery bifurcation and measured perpendicular to a line bisecting the ascending and descending thoracic aorta to approximate a true orthogonal diameter (Figure 1) as described previously12. Mid ascending aortic area was calculated from the linear dimension of the ascending aorta, assuming that the aorta is a perfect circle, using πr2. To assess reproducibility of the aortic measurements, two physicians (CM and DC) experienced in reading cardiac CT’s reviewed 30 cases. The 30 cases were then re-read by one of the physicians (CM) one week after the initial read.

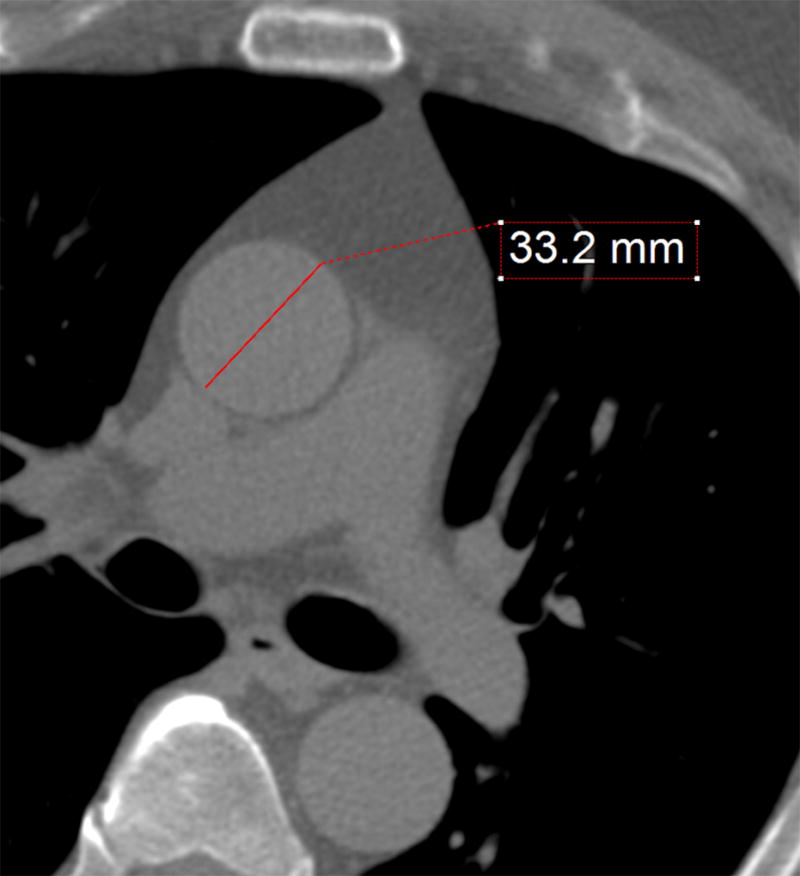

Figure 1. Thoracic Aortic Measurement.

Representative case demonstrating the method used for measuring the ascending aorta. The red line represents the aortic diameter perpendicular to the axis of the aorta on a trans-axial slice at the lower level of the pulmonary artery bifurcation in a normal-sized aorta.

Clinical Definitions

Hypertension was defined as self-reported history of hypertension and on treatment or being hypertensive (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90) based on the average of sequential blood pressure measurements for each subject. Diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported history of diabetes, hemoglobin A1c greater than or equal to 6.5% or use of oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin. Current smoking was defined as any cigarette smoking at the time of screening. Former NFL athletes who played in the tackle, guard, center, defensive tackle, defensive end, or linebacker were classified as linemen; those who played in the quarterback, running back, wide receiver, tight end, cornerback, safety, kicker, or punter position were classified as non-linemen. Aortic enlargement was defined as a mid-ascending aortic dimension greater than 40 mm based on the Task Force 7 (Aortic Disease) of the Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes with Cardiovascular Abnormalities and represents the 99th percentile in male athletes13, 14. Aortic dimension greater than 40 mm is also a common threshold in which at least annual imaging surveillance is recommended and avoidance of intense weight lifting may be considered in athletes.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics for continuous variables are reported as mean (one standard deviation) and categorical variables are reported as frequency (percentage). Participant characteristics were compared between the former NFL and DHS cohorts and between linemen and non-linemen using a Student’s unpaired t-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. Multivariable linear regression models were constructed to delineate variables independently associated with ascending aortic diameter and aortic area indexed for height.

The aortic diameters and aortic area indexed for height were modeled by adjusting for a set of a priori variables that included age, African-American race, systolic blood pressure, hypertension status, diabetes mellitus, current smoking, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), non-HDL-C, and body surface area (BSA). In light of the previously defined relationships between BSA and age with aortic size, we examined predefined interactions between former NFL player status and these covariates. All multivariable linear regression models report standardized β coefficients as the measure of effect size, in which the parameter estimate reflects a one standard deviation change in the aortic diameter and a one standard deviation change in each of the independent variables. Former NFL status was coded as a categorical variable with DHS as the reference group and included in the model as the primary exposure of interest. Similar models were constructed using logistic regression, with aortic size classified as greater than 40 mm. Individuals with missing values for any of the independent variables were excluded from the analysis. The total number of individuals included in each of the final models are listed in the tables.

To further explore the relationship between aortic size, BSA, and age, scatterplots were created, plotting aortic diameter on the y-axis and BSA or age on the x-axis for both adjusted and unadjusted data. For these plots, the best line was plotted along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the regression line. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4, and all statistical tests are two-sided with alpha=0.05.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Of the 484 former NFL athletes screened, 206 fulfilled inclusion criteria. There was no statistically significant difference between the former NFL athletes who underwent a CT scan than those that did not (Supplemental Table 1). Therefore, the study comprised 206 former NFL athletes and 759 male subjects from the DHS. The clinical characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1 including stratification by player position (linemen vs. non-linemen). The former NFL athletes were slightly older (57.1 vs. 53.6 years, p<0.0001), had a higher BSA (2.4 vs. 2.1 m2, p<0.0001) and body mass index (32.4 vs. 30.0 kg/m2, p<0.0001), a lower prevalence of hypertension (36.9% vs. 54.8%, p<0.0001) and current smoking (8.7% vs. 26.5%, p<0.0001) and had a more favorable lipid profile [higher HDL-C (53.9 vs. 48.3, p < 0.0001) and lower non-HDL-C (127.5 vs 143.9, p<0.0001)].

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Former NFL athletes (N = 206) |

DHS (N = 759) |

p value (Former NFL vs. DHS) |

Linemen (N = 93) |

Non- Linemen (N = 113) |

p Value (DHS vs. Linemen vs. Non linemen) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.1+/−10.3 | 53.6+/−8.3 | < 0.0001 | 56.6+/−10.6 | 57.5+/−10.0 | < 0.0001 |

| BSA, m2 | 2.4+/−0.2 | 2.1+/−0.2 | < 0.0001 | 2.5+/−0.2 | 2.3+/−0.2 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.4+/−5 | 30.0+/−5.6 | < 0.0001 | 33.9+/−5.2 | 31.3+/−4.6 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 132.0+/−15.6 | 134.9+/−18 | 0.163 | 133.0+/−15.4 | 131.2+/−15.7 | 0.284 |

| Non-HDL-C, mg/dL | 127.5+/−37.9 | 143.9+/−41.4 | < 0.0001 | 125.5+/−35.8 | 129.1+/−39.8 | < 0.0001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 53.9+/−14.9 | 48.3+/−13.4 | < 0.0001 | 52.5+/−15 | 55.2+/−14.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Aorta, mm | 38+/−5 (47)* | 34+/−4 (42)* | < 0.0001 | 39+/−6 (49)* | 37+/−4 (44)* | < 0.0001 |

| Black | 97 (47.1%) | 400 (52.7%) | 0.158 | 29 (31.2%) | 68 (60.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 76 (36.9%) | 416 (54.8%) | < 0.0001 | 36 (38.7%) | 40 (35.4%) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 31 (15.1%) | 128 (16.9%) | 0.597 | 14 (15.1%) | 17 (15.0%) | 0.824 |

| Current Smoking | 18 (8.7%) | 196 (26.5%) | < 0.0001 | 6 (6.5%) | 12 (10.6%) | < 0.0001 |

Values are mean +/− SD for continuous variable or number (%) for categorical variables. The 95th percentile for each cohort of aortic measurements is represented as (95 percentile)*.

BMI = body mass index; BSA = body surface area; DHS = Dallas Heart Study, HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, NFL = National Football League, SBP = systolic blood pressure

Determinants of Ascending Aortic Dimensions

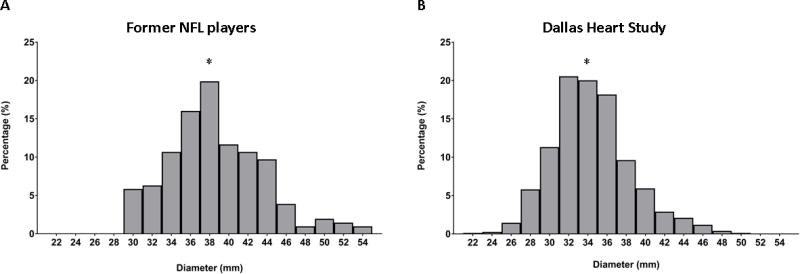

Mean ascending aortic diameter was significantly larger in former NFL athletes compared to controls from the DHS (38±5 mm vs. 34±4 mm, p<0.0001). Distribution of the ascending aortic diameters for each group are shown in Figure 2. Multivariable linear regression models were created adjusting for age, race, systolic blood pressure, history of hypertension and/or diabetes, current smoking, BSA, non-HDL-C, and HDL-C. Former NFL player status remained associated with significantly larger ascending aortic diameters after multivariable adjustment. Furthermore, age, systolic blood pressure, history of hypertension, BSA, and HDL-C level were found to be independently predictive of ascending aortic diameter (Table 2). Former NFL status also predicted larger aortic area indexed to height (standardized β coefficient of 0.2 p<0.001) after adjustment.

Figure 2. Distribution of Ascending Aortic Diameters.

Histograms showing the distribution of ascending aortic diameters in former NFL athletes (Panel A) compared to the Dallas Heart Study (Panel B). Mean ascending aortic diameter in the former NFL athletes were 38 +/− 5 mm compared to 34 +/− 4 mm in the Dallas Heart Study (p < 0.0001). * Denotes mean ascending aortic diameter.

NFL = National Football League.

TABLE 2.

Predictors of Ascending Aortic Diameter

| Risk Factor | Unstandardized Coefficient (Standardized) |

Standard Error | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||

| N = 965; Adjusted R2 = 0.114 | |||

| Former NFL vs. DHS | 0.37 (0.34) | 0.03 | < 0.0001 |

| Constant | 3.44 | 0.02 | < 0.0001 |

| Adjusted | |||

| N = 932; Adjusted R2 = 0.309 | |||

| Former NFL vs. DHS | 0.22 (0.2) | 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| Age | 0.02 (0.37) | 0.0002 | < 0.0001 |

| Black | −0.05 (−0.06) | 0.03 | 0.053 |

| SBP | 0.002 (0.07) | 0.001 | 0.030 |

| Hypertension | 0.07 (0.08) | 0.03 | 0.022 |

| Diabetes | −0.05 (−0.04) | 0.06 | 0.183 |

| Current Smoking | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.03 | 0.918 |

| BSA | 0.38 (0.22) | 0.06 | < 0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C | 0.0003 (0.02) | 0.0003 | 0.393 |

| HDL-C | 0.002 (0.06) | 0.001 | 0.036 |

| Constant | 1.19 | 0.20 | <0.0001 |

BSA = body surface area; DHS = Dallas Heart study; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; N = number; NFL = National Football League; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

In the overall cohort, 126 subjects (13%) had an enlarged ascending aorta greater than 40 mm [former NFL=61 (29.6%); DHS=65 (8.6%)]. On logistic regression modeling, independent predictors of having an ascending aorta greater than 40 mm included being a former NFL player (adjusted OR 1.99; 95% CI 1.14–3.44; p=0.014), age (adjusted OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.65–2.62; p<0.0001), BSA (adjusted OR 1.67; 95% CI 1.29–2.15; p < 0.0001) and HDL-C (adjusted OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.10–1.68; p=0.005) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of an Enlarged Ascending Aorta > 40 mm

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||

| N = 965; N = 126 with aorta > 40 mm | ||

| NFL vs. DHS | 4.49 (3.03, 6.65) | < 0.0001 |

| Adjusted | ||

| N = 932; n = 124 with aorta > 40 mm | ||

| NFL vs. DHS | 1.99 (1.14, 3.44) | 0.014 |

| Age (per 1 SD) | 2.08 (1.65, 2.62) | < 0.0001 |

| Black | 0.78 (0.5, 1.21) | 0.267 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.001 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.923 |

| Hypertension | 1.41 (0.86, 2.3) | 0.175 |

| Diabetes | 0.73 (0.41, 1.32) | 0.297 |

| Current Smoking | 0.66 (0.35, 1.25) | 0.197 |

| BSA (per 1 SD) | 1.67 (1.29, 2.15) | < 0.0001 |

| Non-HDL-C (per 1 SD) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.32) | 0.654 |

| HDL-C (per 1 SD) | 1.36 (1.10, 1.68) | 0.005 |

BSA = body surface area; CI = Confidence interval; DHS = Dallas Heart Study; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NFL = National Football League, SD= standard deviation.

Impact of Player Position

There was a non-significant trend towards having a larger mean ascending aortic diameter in linemen compared to non-linemen (39±6 mm vs. 37±4 mm, p<0.093). Multivariable linear regression modeling was repeated to include player position to evaluate for an association with ascending aortic diameters (Supplemental Table 2). Both types of player positions were independently associated with larger aortic diameters in unadjusted and adjusted models compared to the DHS cohort. Repeat logistic regression modeling was also performed with the inclusion of the player position. The previous predictors remained significant while only former linemen remained independently predictive of an ascending aortic diameter greater than 40 mm (adjusted OR 2.35, p=0.014), albeit in a less powered sub-analysis (Supplemental Table 3).

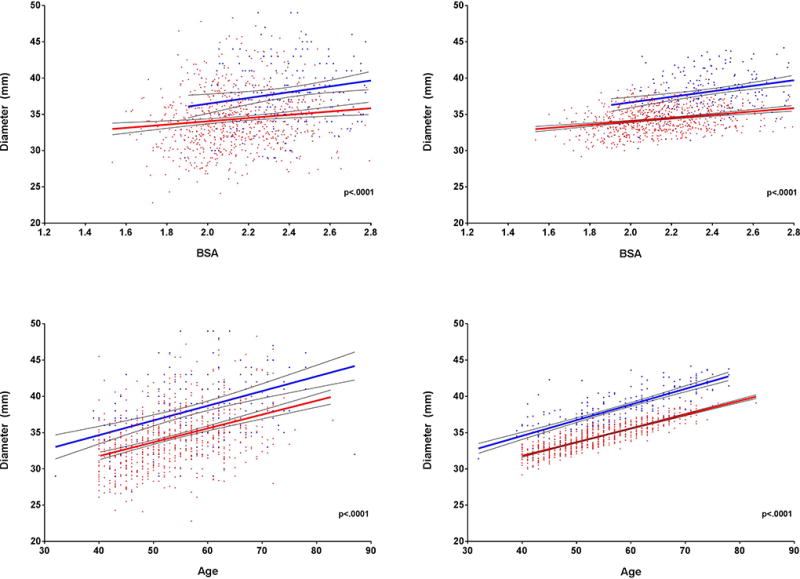

Interaction between BSA and Age

BSA and age are both well documented predictors of aortic size and remain two major predictors of ascending aortic diameters in this study; the relationship between aortic diameter and age and aortic diameter and BSA between the two cohorts is displayed in the Figure 3. Although ascending aortic diameters increase with increasing BSA and increasing age, at any given BSA or age the former NFL cohort has a consistently larger ascending aorta compared to the DHS group. This holds true for unadjusted data and after adjustment for parameters described in Table 2.

Figure 3. Ascending Aortic Diameters in Former NFL Athletes.

Scatterplots showing relationships between ascending aortic diameter and body surface area (1a) and ascending aortic diameter and age (1b) in the former NFL and DHS cohorts. This relationship remains constant after adjustment for age, race, systolic blood pressure, history of hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, body surface area, non-HDL-C and HDL-C (2a and 2b).

DHS = Dallas Heart Study; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein; NFL = National Football League.

Reproducibility Assessment

Interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between independent readers was excellent (0.998; 95% CI 0.997–0.999); similarly, the agreement between reads was excellent (0.998; 95% CI 0.997–0.999).

Discussion

In the present study we compared ascending aortic size using CT in a sample of former NFL athletes to the male DHS cohort. We found that being a former elite athlete was associated with a larger ascending aorta independent of size, age, race, blood pressure, a history of hypertension or diabetes, current smoking status, or lipid profile. Indeed, even after adjustment for these parameters, former NFL athletes had a twofold higher risk of having aortic dilation, as defined by an aorta dimension greater than 40 mm7, 13, 15. When considering the type of NFL player position, prediction of aortic dilation was driven primarily by linemen as opposed to non-linemen.

A number of studies have addressed the issue of aortic dilation in elite athletes actively participating in their sport5, 7–9, 14, 16. The findings of these studies consistently demonstrate that the aorta in active elite athletes falls within the established limits for the general population. The aorta is rarely (<2%) greater than 40 mm; this arbitrary cut off is used in the updated American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (ACC) Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations as a threshold to indicate aortic dilation with recommendations for comprehensive evaluation for an underlying genetic aortopathy, avoidance of intense weight training and close surveillance if above this threshold13. However, in a meta-analysis by Iskandar et al., elite athletes did have significantly larger aortas when compared to sedentary controls, in the order of 3.2 mm larger at the level of the sinus of Valsalva7. The natural history of this finding as athlete’s age is unknown. Overall, the difference in aortic size between the former NFL cohort and the DHS cohort has a comparable magnitude to that seen in the study by Iskander suggesting that athletes may develop slight aortic enlargement during their playing days and stay on the normal age related growth curve. This is supported by data presented in the central illustration where the differences in aortic dimensions between former NFL and DHS remain relatively constant independent of age. However, this does not tell the entire story as seen in Figure 2 where there is a larger skew to the right in the former NFL cohort. Although, in general, the difference in size of the aorta between the former NFL and DHS cohorts appears to be constant across all age groups there is a small but substantial number of former NFL athletes with ascending aortas that would be considered significantly dilated according to currently utilized nomograms15, 17. This finding could be anticipated according to Laplace’s law where the larger aorta will be exposed to proportionally greater wall stress over the course of the athlete’s life.

Increased aortic size in elite athletes may be anticipated given the intense hemodynamic stress placed on the aorta during intensive exercise. Highly trained endurance athletes can increase their cardiac output up to 7-fold; this is associated with prolonged exposure to substantial increases in systolic blood pressure not infrequently above 200 mmHg in men18, 19. Resistance training, on the other hand, can result in a massive transient increase in blood pressure particularly if performed to fatigue or with Valsalva20. Amazingly, a central blood pressure of 480/350 mmHg was recorded on an indwelling arterial catheter in one study of professional body builders lifting one-repetition maximum weight21. The published literature is somewhat at variance regarding whether one type of exercise (endurance versus strength) is associated with greater degrees of aortic dilation5, 8. The training regimen and playing requirements of linemen is primarily resistance based. We found that linemen were more likely to have aortic dilation which is consistent with prior work by D’Andrea et al. who demonstrated larger aortic size and increased aortic stiffness in strength versus endurance trained athletes5.

The literature provides some data to contextualize the numbers reported here, although, the guidelines are somewhat more limited. The 2010 ACC thoracic aortic disease guidelines only provide a measurement of 28.6 mm obtained from reports of chest X-rays without providing a range or accounting for sex, age or BSA15. The 2015 American Society of Echocardiography guidelines only provide data on the aortic root, which is generally slightly larger than the mid-ascending aorta17. Normal ranges are provided for three age groups and according to BSA. The upper limit of the 95% CI in the oldest group with the largest BSA was 44 mm. In our study, 9% of the former NFL group had an aorta that measured ≥ 45 mm. Incidentally, this is also a level at which surgical replacement of the aorta is recommended if the patient is undergoing concomitant cardiac surgery15. In one of the largest studies to date evaluating ascending aortic size in a normal population, Wolak et al. reviewed studies from 4,039 patients who underwent screening CT scans for coronary calcium score. They report an average mid-ascending aortic size of 34±4.1 mm in 2,510 male subjects, identical to the aortic size reported in the DHS cohort in the current study. In Wolak’s study, the upper limit of the 95% CI for the oldest cohort (greater than 65 years) and the largest patients (BSA greater than 2.1 m2) was 42 mm. 19% of our entire former NFL cohort have aortic sizes exceeding this limit. Indeed, of the former NFL cohort who were greater than 65 years old and had a BSA exceeding 2.1 m2, 34% had an ascending aorta that measured greater than 42 mm.

Indexing aortic size for BSA is proposed as an additional/alternative means of recognizing aortic dilation which accounts for anthropometrics; however, it is widely recognized that at the upper extremes of body size there is a plateauing of aortic size elegantly described by Engel et al. in a study of 526 National Basketball Association athletes amongst other studies8, 16, 22, 23. Recent data also suggests the aortic cross-sectional area/height ratio is a robust predictor of outcome24, 25. Despite the limitations of using indexed aortic size in larger individuals, when we repeated our analysis indexing aortic area to height our data continued to demonstrate that being a former NFL player remain significantly predictive of a larger aortic cross-sectional area/height ratio compared to the DHS cohort even after adjustment for multiple risk factors known to influence aortic size.

Study Limitations

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to evaluate the natural history of aortic size in elite athletes. Given the relatively small number of former athletes involved, this data should be considered hypothesis generating. The findings are specific to a small select group of former NFL athletes with the potential for selection bias and which may not reflect the entire former NFL population. Further studies should be done in different cohorts of former athletes to corroborate this finding. Potential bias may exist given the assumption that DHS participants were not former elite athletes (although this would bias the findings towards the null hypothesis). We cannot comment on whether this finding results in excessive aortic complications later in life or whether this is a normal adaptation of the aorta and, absent an underlying aortopathy, attributes no additional risk to the individual. On our review of the literature, there is no data to suggest that youthful participation in athletic activity contributes a higher risk of aortic dissection or rupture. This is an important area of research as recommendations regarding timing of initiation of medical therapy, activity restrictions, and even surgical indications would potentially be influenced.

Conclusion

Ascending aortic dimensions are significantly larger in a select sample of former NFL athletes compared to a presumed non-elite athletic cohort even after accounting for their size and multiple risk factors known to influence aortic size. This may be related to the hemodynamic stress of repetitive strenuous exercise over many years. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown and will require further evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Former National Football League athletes have significantly larger aortas when compared to controls. This is independent of age, body habitus or risk factors for aortic dilation and likely reflects adaptation to the hemodynamic stress of repetitive strenuous exercise over many years. When evaluating a patient with an enlarged aorta, a history of longstanding athletic activity should be noted. The clinical significance of this finding is unknown future studies are needed to evaluate whether these changes translate into negative clinical outcomes or are merely adaptive.

Footnotes

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported in part by the National Football League in association with the NFL Players Care Foundation Healthy Body and Mind Screening Program. The Dallas Heart Study was supported in part by grant UL1TR001105 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures:

This work supported in part by the National Football League and grant UL1TR001105 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science and the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Spirito P, Pelliccia A, Proschan MA, Granata M, Spataro A, Bellone P, Caselli G, Biffi A, Vecchio C, Maron BJ. Morphology of the “athlete's heart” assessed by echocardiography in 947 elite athletes representing 27 sports. The American journal of cardiology. 1994;74:802–806. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Utomi V, Oxborough D, Whyte GP, Somauroo J, Sharma S, Shave R, Atkinson G, George K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of training mode, imaging modality and body size influences on the morphology and function of the male athlete's heart. Heart. 2013;99:1727–1733. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morganroth J, Maron BJ, Henry WL, Epstein SE. Comparative left ventricular dimensions in trained athletes. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:521–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-4-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner RB, Wang F, Isaacs SK, Malhotra R, Berkstresser B, Kim JH, Hutter AM, Picard MH, Wang TJ, Baggish AL. Blood pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy during american-style football participation. Circulation. 2013;128:524–531. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Andrea A, Cocchia R, Riegler L, Salerno G, Scarafile R, Citro R, Vriz O, Limongelli G, Di Salvo G, Caso P. Aortic stiffness and distensibility in top-level athletes. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2012;25:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigi MAB, Aslani A. Aortic root size and prevalence of aortic regurgitation in elite strength trained athletes. The American journal of cardiology. 2007;100:528–530. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iskandar A, Thompson PD. A meta-analysis of aortic root size in elite athletes. Circulation. 2013;127:791–798. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boraita A, Heras M-E, Morales F, Marina-Breysse M, Canda A, Rabadan M, Barriopedro M-I, Varela A, de la Rosa A, Tuņón J. Reference values of aortic root in male and female white elite athletes according to sport. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2016;9:e005292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinoshita N, Mimura J, Obayashi C, Katsukawa F, Onishi S, Yamazaki H. Aortic root dilatation among young competitive athletes: Echocardiographic screening of 1929 athletes between 15 and 34 years of age. American heart journal. 2000;139:723–728. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, Peshock RM, Vaeth PC, Leonard D, Basit M, Cooper RS, Iannacchione VG, Visscher WA. The dallas heart study: A population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. The American journal of cardiology. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budoff MJ, Achenbach S, Blumenthal RS, Carr JJ, Goldin JG, Greenland P, Guerci AD, Lima JA, Rader DJ, Rubin GD. Assessment of coronary artery disease by cardiac computed tomography. Circulation. 2006;114:1761–1791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.178458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolak A, Gransar H, Thomson LE, Friedman JD, Hachamovitch R, Gutstein A, Shaw LJ, Polk D, Wong ND, Saouaf R. Aortic size assessment by noncontrast cardiac computed tomography: Normal limits by age, gender, and body surface area. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2008;1:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braverman AC, Harris KM, Kovacs RJ, Maron BJ. Eligibility and disqualification recommendations for competitive athletes with cardiovascular abnormalities: Task force 7: Aortic diseases, including marfan syndrome. Circulation. 2015;132:e303–e309. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelliccia A, Di Paolo FM, Quattrini FM. Aortic root dilatation in athletic population. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2012;54:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, Eagle KA, Hermann LK, Isselbacher EM, Kazerooni EA. 2010 accf/aha/aats/acr/asa/sca/scai/sir/sts/svm guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55:e27–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Andrea A, Cocchia R, Riegler L, Scarafile R, Salerno G, Gravino R, Vriz O, Citro R, Limongelli G, Di Salvo G. Aortic root dimensions in elite athletes. The American journal of cardiology. 2010;105:1629–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein SA, Evangelista A, Abbara S, Arai A, Asch FM, Badano LP, Bolen MA, Connolly HM, Cuéllar-Calàbria H, Czerny M. Multimodality imaging of diseases of the thoracic aorta in adults: From the american society of echocardiography and the european association of cardiovascular imaging: Endorsed by the society of cardiovascular computed tomography and society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2015;28:119–182. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caselli S, Segui AV, Quattrini F, Di Gacinto B, Milan A, Assorgi R, Verdile L, Spataro A, Pelliccia A. Upper normal values of blood pressure response to exercise in olympic athletes. American heart journal. 2016;177:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palatini P. Exercise haemodynamics: Field activities versus laboratory tests. Blood pressure monitoring. 1997;2:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayerick C, Carré F, Elefteriades J. Aortic dissection and sport: Physiologic and clinical understanding provide an opportunity to save young lives. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2010;51:669–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDougall J, Tuxen D, Sale D, Moroz J, Sutton J. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1985;58:785–790. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engel DJ, Schwartz A, Homma S. Athletic cardiac remodeling in us professional basketball players. JAMA cardiology. 2016;1:80–87. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed CM, Richey PA, Pulliam DA, Somes GW, Alpert BS. Aortic dimensions in tall men and women. The American journal of cardiology. 1993;71:608–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90523-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masri A, Kalahasti V, Svensson LG, Roselli EE, Johnston D, Hammer D, Schoenhagen P, Griffin BP, Desai MY. Aortic cross-sectional area/height ratio and outcomes in patients with a trileaflet aortic valve and a dilated aorta. Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022995. CIRCULATIONAHA. 116.022995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Svensson LG, Kim K-H, Lytle BW, Cosgrove DM. Relationship of aortic cross-sectional area to height ratio and the risk of aortic dissection in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126:892–893. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)00608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.