Abstract

Introduction

The epidemic of nonmedical use of prescription opioids (NMUPO) has been fueled by the availability of legitimately prescribed unconsumed opioids. The aim of this study was to better understand the contribution of prescriptions written for pediatric patients to this problem by quantifying how much opioid is dispensed and consumed to manage pain following hospital discharge, and whether leftover opioid is appropriately disposed of. Our secondary aim was to explore the association of patient factors with opioid dispensing, consumption and medication remaining upon completion of therapy.

Methods

Using a scripted 10-minute interview, parents of 343 pediatric inpatients (98% post-operative) treated at a university children’s hospital were questioned within 48 hours and 10–14 days after discharge to determine amount of opioid prescribed and consumed, duration of treatment, and disposition of unconsumed opioid. Multivariable linear regression was used to examine predictors of opioid prescribing, consumption, and doses remaining.

Results

Median number of opioid doses dispensed was 43 (IQR, 30–85 doses), and median duration of therapy was 4 days (IQR, 1–8 days). Children who underwent orthopedic or Nuss surgery consumed 25.42 [95% CI, 19.16–31.68] more doses than those who underwent other types of surgery (p < 0.001), and number of doses consumed was positively associated with higher discharge pain scores (p = 0.032). Overall 58% [95% CI, 54%–63%] of doses dispensed were not consumed, and the strongest predictor of number of doses remaining was doses dispensed (p < 0.001). Nineteen percent of families were informed how to dispose of leftover opioid, but only 4% (8/211) did so.

Discussion

Pediatric providers frequently prescribed more opioid than needed to treat pain. This unconsumed opioid may contribute to the epidemic of NMUPO. Our findings underscore the need for further research to develop evidence-based opioid prescribing guidelines for physicians treating acute pain in children.

Introduction

While the alleviation of pain is fundamental to the practice of medicine and surgery, in the past pain was often undermanaged or ignored.1 In recent years, assessment and treatment of pain have become quality indicators in healthcare,2,3 a change associated with a dramatic increase in opioid prescribing. In 2009, over one billion opioid pills were dispensed in Florida alone.4 When used to treat acute pain, opioids are safe and effective.5,6 Unfortunately, as opioid prescribing increased, risks associated with opioid use and misuse were downplayed.7,8

Today, nonmedical use of prescription opioids (NMUPO) has reached epidemic levels in the United States, resulting in numerous accidental drug poisoning deaths and opioid-related treatment admissions.7,9 The resulting public health response to this crisis must be aimed at minimizing the risk of opioid misuse while continuing to meet the needs of patients in pain. To date, most regulatory, medical, and research activity devoted to NMUPO has focused on chronic opioid use in non-cancer pain,5,10 and little attention has focused on acute pain in general or pediatric pain in particular,11 even though the risk of prescription opioid abuse is highest in adolescents and young adults.12

The purpose of this study was to characterize opioid prescribing to pediatric patients upon hospital discharge to better understand the potential impact of pediatric acute pain management on this epidemic. Therefore, we sought to determine the amount and formulation of opioids prescribed, and to estimate the duration and effectiveness of treatment and the amount of medication remaining at the end of therapy, as well as the disposition of leftover medication. Our secondary aim was to explore the association of patient factors with opioid prescribing, consumption, and amount of medication remaining at completion of therapy as a preliminary step to guide future research and the development of safe, evidence-based prescribing recommendations for the treatment of pain in children.

Methods

Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, parental consent, and, when appropriate, patient consent or assent, we studied male and female inpatients, 1 to 21 years of age, treated by the Pediatric Pain Service (PPS) of the Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children’s Center (October 2014-December 2015). The PPS is a consultative service that treats pediatric inpatients experiencing moderate-to-severe pain as a result of surgery and/or painful medical conditions. The service is responsible for providing analgesic therapy to all inpatients receiving intravenous opioids via patient or parent/nurse controlled analgesia (except those admitted for management of sickle cell disease), and all catheter-delivered analgesics (neuraxial and peripheral nerve).

Prior to hospital discharge, patients followed by the PPS were transitioned to multimodal analgesia including oral opioids as appropriate, and upon discharge opioids were prescribed by the patient’s primary service based on patient needs and provider preference. Because a primary aim of this study was to better understand dispensing, consumption, and disposition of unused opioid, enrollment was limited to patients/families discharged from the hospital with an opioid prescription. Discharge prescriptions were generated with the hospital’s computerized narcotic prescription writer13 and analyzed to determine medication(s) prescribed, drug formulation, dosing frequency, and quantity of drug dispensed. Surgical procedures and/or medical diagnoses, hospital length of stay, pain score upon discharge, and the ages of all children in the household were documented. Patients/parents who were non-English speaking, did not have telephone access, or lacked capacity to consent were excluded.

Within 48 hours and again 10–14 days after discharge, parents were contacted by telephone to participate in a scripted 10-minute interview (Appendix A). If parents were not reached, up to two additional attempts were made. During these interviews, we determined if prescriptions were filled, how well pain was controlled, how long opioids were used, why therapy was stopped, and how much opioid remained at reported completion of therapy. If opioid consumption was no longer ongoing at the time of the initial or 10–14 day interview, we ascertained when dosing had stopped. If available, children 7 and older were asked to rate pain using numeric self-report (NRS; 0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain). Children under 7 were assessed with the Parents’ Postoperative Pain Measure (PPPM).14 Moderate-to-severe pain was defined by an NRS > 4/10 or a PPPM > 5/15. At the conclusion of the second interview, parents were asked if they were given instructions concerning disposal of unused medications and if they had done so. If they had not been given instructions, recommendations were provided. This manuscript adheres to the applicable Equator guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for skewed data. Patients were grouped by demographic and admission characteristics (e.g., age, race, gender, surgical type/provider service). Children were grouped into 4 age ranges: 1–2 years, 3–7 years, 8–14 years and 15–21 years of age for comparisons. Outcome measures (amount of opioid prescribed, consumed and left-over) were compared between these specific groups using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s test with Hochberg adjustments for post hoc multiple comparisons. Number of opioid doses prescribed and remaining were also compared between those who thought they received too little, too much, or the appropriate amount of opioid.

Multivariable linear regression models with robust variance estimates15,16 were fit to estimate the relationship between demographic data and admission characteristics and the following dependent variables: number of doses prescribed, number remaining when consumption was no longer ongoing, and number consumed (defined as doses prescribed – doses remaining). A priori selected predictor variables included age, sex, race, hospital length of stay (natural logarithm), surgical type (Nuss + orthopedic surgery versus other), and pain score at time of hospital discharge. Discharge pain score was categorized to differentiate 3 levels of pain: no pain (0/10), mild pain (1–4/10), and moderate-to-severe pain (≥5/10), and was represented with two indicator variables (1–4/10 versus 0 and ≥ 5/10 versus 0) in the model. The model for doses remaining also included number of prescribed doses as a predictor.

Regression diagnostics were performed to assess linear fit, homoscedasticity, and normality of residuals. Linear splines were used to account for deviation from linear fit for age with a knot at 15 years of age, and separate slopes were estimated for age < 15 years and ≥ 15 years. P < 0.05 (2-tailed) was considered to indicate statistical significance. In order to account for multiple comparisons, we added frequentist q-values17 for the regression models. These are corrected p-values to control the positive False Discovery Rate using Simes multiple test procedure.18 Using this False Discovery Rate methodology we set the maximum allowable proportion of incorrectly rejected null hypotheses (i.e., “false discoveries”) to 5%. This is less conservative than controlling the experiment-wise type I error (probability of any false positive finding) at 5%. The procedure outputs “adjusted” p-values (or q-values) that define the discovery set that controls the False Discovery Rate. Q-values < 0.05 are included in the discovery set and are considered “statistically significant.”

Power analysis based on simple and multiple linear regression analysis looking at the association between a primary independent variable and a dependent variable (such as doses dispensed or consumed) with and without adjustment for other variables, such as age, gender, race, surgical type, length of stay, and discharge pain score was carried out using PASS statistical software.19 For a simple linear regression with N = 235, we had an 80% power to detect a standardized linear slope coefficient of 0.18 vs. 0 (under the null hypothesis) at 0.05 level of significance. For example, for doses dispensed as the dependent variable, the standard deviation is 45 doses. Therefore, a standardized slope of 0.18 corresponds to a linear slope of 8 for a primary continuous predictor with a standard deviation of 1. We further assumed 10% R-squared for a multivariable model without a primary predictor (such as doses dispensed), and calculated the amount added to the overall R-squared value by including the primary predictor that is associated with 80% power. Our calculations showed that we had 80% power to detect at least 3% increase in R-squared attributed to this primary predictor, after adjustment for other covariates.

Study data were managed using REDCap® electronic data capture tools20 and analyzed using Stata version 14 (Statacorp, 2015 Stata Statistical Software: Release 14, College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

During this 14-month study 630 patient families were approached prior to hospital discharge and 587 consented to participate. Sixty-six families were subsequently rendered ineligible as a result of being discharged home without an opioid prescription (n = 41), screen failure (did not meet inclusion criteria by age (n = 3), patient not discharged home with family (n = 14), or readmission to the hospital during the study period (n = 8). Of the 521 families who were called, 343 (66%) completed at least one interview and 102 completed both. Patient demographics, admission characteristics, and opioids prescribed are shown in Table 1. Amount of opioid dispensed and remaining, and effectiveness of treatment are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics, Admission Characteristics, and Opioids Prescribed

| Characteristic | Number (%) of all respondents (n = 343) | Number (%) of respondents reporting outcome* (n = 235) | Number (%) of respondents not reporting outcome (n = 108) | p - value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.86 | |||

| Male | 169 (49) | 115 (49) | 54 (50) | |

| Female | 174 (51) | 120 (51) | 54 (50) | |

| Race | 0.27 | |||

| White | 228 (67) | 164 (70) | 64 (59) | |

| Black or African American | 62 (18) | 40 (17) | 22 (20) | |

| Asian | 21 (6) | 13 (6) | 8 (7) | |

| Other | 32 (9) | 18 (8) | 14 (13) | |

| Age (years) | 11±5a | 11±5 | 11±5 | 0.82 |

| 1–2 | 30 (9) | 19 (8) | 11 (10) | |

| 3–7 | 68 (20) | 47 (20) | 21 (19) | |

| 8–14 | 140 (41) | 94 (40) | 46 (43) | |

| 15–21 | 105 (31) | 75 (32) | 30 (28) | |

| Number of families with siblings living at home | 0.048 0.23 |

|||

| All ages | 256 (75) | 168 (72) | 88 (81) | |

| Adolescents | 152 (44) | 99 (42) | 53 (49) | |

| Primary service | 0.38 | |||

| Cardiac surgery | 7 (2) | 5 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Neurosurgery | 23 (7) | 19 (8) | 4 (4) | |

| General surgery | 44 (13) | 28 (12) | 16 (15) | |

| Urology | 51 (15) | 36 (15) | 15 (14) | |

| Plastic surgery | 48 (14) | 38 (16) | 10 (9) | |

| Orthopedic surgery | 157 (47) | 101 (43) | 56 (52) | |

| Posterior spinal fusion | 86 (55) | 54 (23) | 29 (27) | |

| Other surgical specialty | 7 (2) | 5 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Medical | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | |

| Hospital length of stay | 3 (2–5)b days | 3 (2–5) days | 4 (3–6) days | 0.018 |

| 0–2 days | 111 (32) | 87 (37) | 24 (22) | |

| 3–4 days | 124 (36) | 82 (35) | 42 (39) | |

| ≥ 5 days | 108 (31) | 66 (28) | 42 (39) | |

| Pain Score at Discharge | 0.35 | |||

| 0/10 | 171 (50) | 114 (49) | 57 (53) | |

| 1–4/10 | 107 (31) | 71 (30) | 36 33) | |

| ≥ 5/10 | 65 (19) | 50 (21) | 15 (14) | |

| Number of opioid prescriptions filled | 328 (96) | 226 (96) | 102 (94) | 0.70 |

| Opioid Prescribed | 0.37 | |||

| Oxycodone | 301 (88) | 204 (87) | 97 (90) | |

| Liquid | 155 (52) | 109 (53) | 46 (47) | |

| Tablet | 146 (48) | 95 (47) | 41 (53) | |

| Hydromorphone | 28 (8) | 23 (10) | 5 (5) | |

| Liquid | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Tablet | 26 (93) | 22 (96) | 5 (100) | |

| Morphine IR | 11 (3) | 6 (3) | 5 (5) | |

| Liquid | 8 (73) | 3 (50) | 5 | |

| Tablet | 3 (27) | 3 (50) | 0 | |

| Morphine ER | 1 (< 1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Methadone | 2 (< 1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

Outcome is number of doses remaining

Comparing respondents reporting and not reporting outcome

Mean ± standard deviation

Median and interquartile ranges (25th – 75th percentile)

Table 2.

Opioid Doses Dispensed and Remaining and Analgesic Effectiveness

| Doses Dispenseda All respondents (n = 343) | Doses Dispensed/Doses Remaininga Respondents reporting outcome* (n = 235) | Doses Dispensed Respondents not reporting outcome (n = 108) | p – value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 43 (30 – 85) | 42 (30 – 80) | 55 (30 – 101) | 0.058 |

| 25 (11 – 42) | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 42 (30 – 75) | 41 (30–72) | 42 (30 – 84) | 0.27 |

| 28 (12 – 41) | ||||

| Female | 55 (39 – 96) | 48 (30 – 84) | 61 (30 – 113) | 0.079 |

| 25 (10 – 42) | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 1–2 | 31 (30 – 40) | 31 (30 – 33) | 31 (17 – 60) | 0.85 |

| 23 (15 – 32) | ||||

| 3–7 | 31 (30 – 50) | 31 (30 – 50) | 31 (30 – 55) | 0.79 |

| 21 (9 – 31) | ||||

| 8–14 | 42 (30 – 66) | 46 (30 – 77) | 72 (42 – 113) | 0.009 |

| 29 (14 – 48) | ||||

| 15–21 | 60 (40 – 113) | 60 (30 – 113) | 60 (30 – 113) | 0.55 |

| 28 (9 – 45) | ||||

| Primary service | ||||

| Cardiac surgery | 11 (10 – 15) | 10 (10 – 12) | 15 (15–15) | 0.37 |

| 10 (5 – 12) | ||||

| Neurosurgery | 30 (30 – 60) | 30 (30 – 43) | 45 (30–72) | 0.24 |

| 20 (9 – 30) | ||||

| General surgery | 43 (30 – 80) | 42 (39 – 82) | 43 (30 – 60) | 0.94 |

| 31 (18 – 46) | ||||

| Urology | 31 (30 – 32) | 31 (30 – 33) | 31 (30 – 32) | 0.77 |

| 19 (8 – 31) | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 30 (30 – 42.5) | 30 (25 – 42) | 42 (30 – 61) | 0.049 |

| 21 (9 – 30) | ||||

| Orthopedic surgery | 80 (48 – 113) | 76 (48 – 113) | 90 (54 – 113) | 0.70 |

| 30 (15 – 56) | ||||

| Posterior spinal fusion | 113 (80 – 115) | 113 (77 – 115) | 113 (90 – 115) | 0.81 |

| 39 (20 – 80) | ||||

| Other surgical specialty | 30 (12 – 42) | 36 (12 – 42) | 22.5 (15–30) | 0.70 |

| 18 (0 – 38) | ||||

| Medical | 51 (30 – 60) | 60 (15 – 84) | 42 (30 – 60) | 0.66 |

| 52 (11 – 84) | ||||

| Effectiveness of Analgesiab | 1–2 days post discharge (n = 195) | 10–14 days post discharge (n = 216) | ||

| Excellent | 48% | 46% | ||

| Good | 38% | 44% | ||

| Fair | 12% | 8% | ||

| Poor | 1% | 2% | ||

Outcome is number of doses remaining

Comparing respondents reporting and not reporting outcome

Median and interquartile ranges (25th – 75th percentile)

As reported by caretakers

Patients were treated for 109 unique diagnoses, most involving a surgical procedure. Patients who did not undergo surgery most frequently were treated for soft tissue infection or skin breakdown (n = 6, 2%). Surgeons wrote 98% of all prescriptions; 46% were written by orthopedic surgeons. The most common surgeries performed by service included posterior spinal fusion, upper/lower extremity osteotomy, repair of hypospadias, ureteral reimplantation, cleft palate repair, burn grafting, repair of pectus excavatum (Nuss procedure), laparoscopic abdominal surgery, suboccipital craniotomy for Chiari malformation, craniotomy for tumor, and closure of atrial septal defect. With the exception of those undergoing posterior spinal fusion surgery (n = 86, 25%), the number of patients undergoing even the most common procedures was generally less than 7% of the total number of patients studied precluding analyzing data by specific procedure. For this reason surgical patients were generally grouped by provider service with the exception of those who underwent spinal fusion or Nuss procedure (n = 13), two procedures which in our clinical experience are routinely associated with moderate-to-severe pain both during and after hospitalization.

Oxycodone was the most frequently prescribed opioid. Long-acting opioids, such as methadone, extended release morphine, and Oxycontin®, were rarely prescribed and no prescriptions were written for codeine or combination medications such as Vicodin® (Table 1). However, 279 respondents (81%) reported taking over-the-counter adjuvant analgesics—acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen—along with their prescription opioid at some point after discharge. Further, 162 patients (47%) were also prescribed oral diazepam for pain and muscle spasm control. Of these, 70% underwent orthopedic surgery and 22% urologic surgery.

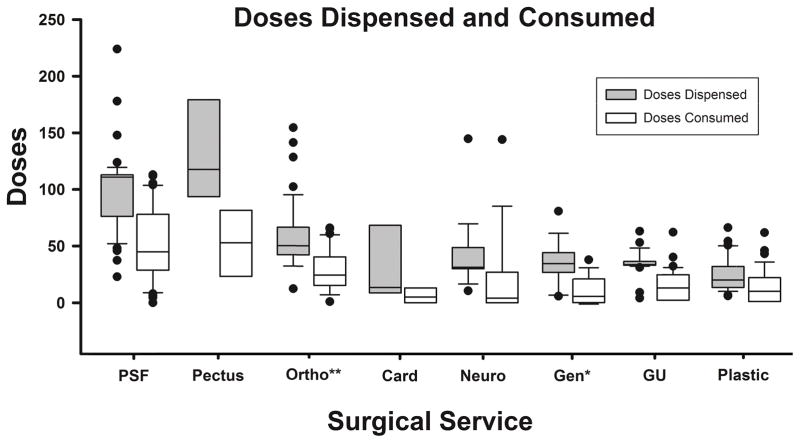

Median number of opioid doses prescribed per patient was 43 (IQR, 30–85) (Table 2). Focusing only on respondents who also reported doses remaining, median doses prescribed was 42 (IQR, 30–80). Number of doses dispensed for females and males did not statistically differ (p = 0.097). Children less than 3 years of age were prescribed an estimated 35.2 [95% CI, 19.6–51.8] fewer doses than those 15 years and older (p < 0.001). Children who underwent spinal fusion or Nuss procedures were prescribed the most opioid (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Doses Dispensed and Consumed by Surgical Specialty.

Number of opioid doses dispensed and consumed following hospital discharge by surgical specialty/procedure. Data presented as medians and interquartile ranges with outliers depicted as points.

Among those reporting doses remaining, the median number of opioid doses consumed was 16 (IQR, 2–39). Females consumed an estimated 9 [95% CI, 1.7–16.3, p = 0.02] more opioid doses than males, and children less than 3 years of age consumed an estimated 23.7 [95% CI, 7.6–39.9] fewer doses than those 15 years and older (p = 0.005). Patients who underwent posterior spinal fusion (n = 54; median doses consumed 53; IQR, 25–79) or Nuss procedure (n = 9; median doses consumed 42; IQR, 36–75) consumed the most opioid after discharge (Figure 1). Patients who underwent non-spine orthopedic surgery had the third highest observed consumption (n = 47, median doses consumed 24; IQR, 14–40), while number of doses consumed following plastic, urologic, general (excluding Nuss procedure), cardiac or neurosurgery were significantly lower (n = 125, median doses consumed 6, IQR, 0–18, p < 0.001 versus all orthopedic and Nuss surgery).

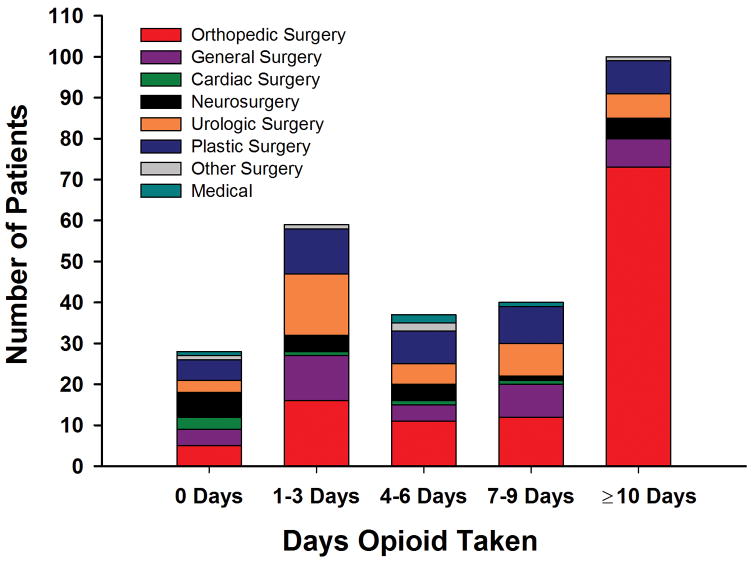

Median duration of outpatient opioid therapy was 4 days (n = 199, IQR, 1–8 days), but over half (52%) of all patients needed opioid to treat pain for more than 3 days, and 124 (36%) were still taking opioids 7 days after discharge (Figure 2). Of the 91 (27%) patients whose parents reported that they received opioid therapy for more than 10 days, 80% had undergone orthopedic or Nuss surgery.

Figure 2. Duration of Opioid Use by Specialty.

Duration of opioid therapy (days) reported by families following hospital discharge. Data are stratified by primary service.

Overall, an estimated 58% [95% CI, 54%–63%] of doses dispensed remained unconsumed after opioid therapy was no longer required to treat pain. Eighty-two percent of patients (192/235) had more than 20% of dispensed opioid remaining upon completion of therapy, 53% (n = 125) had more than 50% remaining, and 33% (n = 77) had more than 80% of doses remaining. Most parents who provided a reason for stopping their child’s opioids during the phone call at 10–14 days reported doing so because pain was well controlled (133/174). However, 18% stopped therapy because of opioid-induced side effects, most commonly gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting) or neurologic symptoms (change in personality, excessive sleepiness).

At discharge 50% (171/343) of patients had a recorded pain score of 0/10, 31% (107/343) had pain scores of 1–4/10, and 19% (65/343) had scores ≥ 5/10, indicating moderate-to-severe pain. During the first interview, over half (75/149) of all children on whom pain information was available had a self-report or parental assessment score consistent with moderate-to-severe pain. Pain scores decreased with time, but even at 10–14 days, 28% (39/140) still had significant pain. Nevertheless, most parents perceived that the prescribed analgesic regimen successfully managed their child’s pain (Table 2). Of note, 51% of parents (115/225) said they had received the right amount of medication, even though the median number of doses remaining was 20 (IQR, 8–33). Despite receiving a similar number of opioid doses, at the two week phone call 37% of families felt too much opioid had been dispensed. These families had significantly more opioid doses remaining (median, 32; IQR, 21–57; p < 0.001). Conversely, families who thought they had received too little medication (12%), had fewer opioid doses remaining (median, 5; IQR, 0–13; p < 0.001).

Calculating the cumulative amount of leftover opioid among the 235 reporting respondents, we found that unconsumed opioid included 3,110 oxycodone tablets and 7,264 mL of oxycodone elixir (22,814 mg oxycodone), 1,138 hydromorphone tablets (2,388 mg hydromorphone), 44 morphine tablets and 599 mL of morphine elixir (1,800 mg morphine), totaling 45,573 morphine mg equivalents. Only 43 of 232 families (19%) said they had been told how to how to dispose of their leftover opioid. Whether they were given this information or not, however, only 4% (8/211) reported having done so, suggesting that most of this opioid remained in the home when no longer required to treat pain.

Focusing on postoperative patients with documented electronic opioid prescriptions (n = 337) and using a multivariable linear regression model that included age, sex, race, hospital length of stay, surgical type (orthopedic + Nuss surgery versus other), and pain score at discharge to look for predictors of number of doses prescribed (Table 3), we found that 36% of the variance in number of doses dispensed could be explained by the covariates age, gender, race, surgical type, length of stay and pain score at discharge. Controlling the positive False Discovery Rate using the Simes multiple test procedure, 3 covariates were statistically significant at the 0.05 level. Age was positively associated with dose dispensed for children < 15 years of age (p < 0.001) and negatively associated with dose dispensed for children aged ≥ 15 years (p = 0.017) after adjustment for other covariates. Children who underwent orthopedic or Nuss surgery were prescribed on average 44.13 more doses than children who underwent other surgeries [95% CI, 34.72–53.54 doses, p < 0.001], after controlling for other covariates. Length of stay (natural logarithm) was positively associated with number of doses dispensed as well; for every 10% increase in length of stay, the number of doses consumed increased by 1.1 [95% CI, 0.4–1.7, p = 0.003].

Table 3.

Linear Regression with Robust Variance to Assess Predictors for Doses Prescribed

| Unadjusted Models with each predictor | Fully Adjusted Model (with all predictors) | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Beta Coefficient (95%CI), p-value | ||

| Age (per 5-year increment) | ||

| Age < 15 | 18.03*** | 8.511*** |

| [13.64,22.42], <0.001 | [4.361,12.66], <0.001 | |

| Age ≥ 15 | −35.21*** | −21.40** |

| [−54.78, −15.63], <0.001 | [−37.13, −5.664], 0.008 | |

| Natural logarithm of length of stay (days) | 9.711* | 11.42** |

| [2.282,17.14], 0.011 | [4.561,18.29], 0.001 | |

| Male vs. Female | −10.59* | −6.820 |

| [−20.21, −0.982], 0.031 | [−14.76,1.116], 0.092 | |

| Caucasian vs. other race | 5.070 | 2.380 |

| [−4.388,14.53], 0.292 | [−5.363,10.12], 0.546 | |

| Orthopedic surgery vs. other procedure | 48.30*** | 44.13*** |

| [40.06,56.53], <0.001 | [34.72,53.54], <0.001 | |

| Discharge pain score category† | ||

| 1–4/10 vs. 0 | 19.44*** | 2.203 |

| [8.806,30.07], <0.001 | [−9.352,13.76], 0.708 | |

| ≥ 5/10 vs. 0 | 24.49*** | 1.456 |

| [12.12,36.86], <0.001 | [−12.04,14.96], 0.832 | |

| N | 337 | 337 |

| R2 | 36% | |

95% confidence intervals in brackets

For the Fully Adjusted Model, corrected p-values (q-values) using Simes multiple test procedure are reported. Corrected p-values < 0.05 are statistically significant.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

p-value for association of discharge pain score with doses prescribed (from chi-square test with two degrees of freedom) < 0.001 in the simple linear regression and 0.930 in the multivariable linear regression

Considering opioid consumption upon discharge, there were 3 statistically significant predictors of doses consumed: gender, surgical type, and discharge pain score (Table 4). Girls on average consumed 7.5 more doses [95% CI, 1.46–13.54, p = 0.043] than boys, after controlling for covariates. Children who underwent orthopedic or Nuss surgery consumed 25.42 [95% CI, 19.16–31.68, p < 0.001] more doses than those who underwent other types of surgery, and a discharge pain score ≥ 5/10 was associated with consuming on average 13.96 more doses as compared to a discharge pain score of 0 [95% CI, 3.74–24.17, p = 0.032] after controlling for other covariates in the model.

Table 4.

Linear Regression with Robust Variance to Assess Predictors for Doses Consumed

| Unadjusted Models with each predictor | Fully Adjusted Model (with all predictors) | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Beta Coefficient (95%CI), p-value | ||

| Age (per 5-year increment) | ||

| Age < 15 | 9.71*** | 3.09 |

| [5.55,13.86], <0.001 | [−1.46,7.64], 0.325 | |

| Age ≥ 15 | −8.20 | −5.48 |

| [−25.31,8.91], 0.35 | [−18.21,7.261], 0.510 | |

| Logarithm of length of stay (days) | 3.25 | 3.18 |

| [−0.86,7.37], 0.12 | [−0.53,6.89], 0.204 | |

| Male vs. Female | −9.029* | −7.50* |

| [−16.31, −1.75], 0.015 | [−13.54, −1.46], 0.043 | |

| Caucasian vs. other race | 0.94 | −1.05 |

| [−6.78,8.66], 0.81 | [−6.88,4.78], 0.724 | |

| Orthopedic/Nuss surgery vs. other procedure | 29.52*** | 25.42*** |

| [22.95,36.08], <0.001 | [19.16,31.68], <0.001 | |

| Discharge pain score category | ||

| 1–4/10 vs. 0 | 11.83** | 1.83 |

| [4.13,19.54], 0.003 | [−5.84,9.50], 0.718 | |

| ≥ 5/10 vs. 0 | 26.67*** | 13.96** |

| [16.31,37.04], <0.001 | [3.74,24.17], 0.032 | |

| N | 235 | 235 |

| R2 | 0.34 | |

95% confidence intervals in brackets

For the Fully Adjusted Model, corrected p-values (q-values) using Simes multiple test procedure are reported. Corrected p-values < 0.05 are statistically significant.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Finally, looking at number of doses remaining using a model that included these variables as well as number of doses dispensed, we found the number of doses dispensed to be the strongest predictor of number of doses remaining (p < 0.001). The estimated beta coefficient is approximately 0.6, which means that for every 1 dose dispensed, on average 0.6 doses were left over when controlling for other covariates. This model also predicts that for the same levels of other covariates, a discharge pain score ≥ 5/10 is associated with 13 [95% CI, −3.9 to −22.06] fewer doses left over (p = 0.025 for Chi-square with 2 degrees of freedom). This full model explains approximately 51% of the variance in number of doses leftover.

Discussion

In this prospective observational study of English-speaking, primarily surgical pediatric inpatients on hospital discharge, multimodal pain management including oral opioid analgesics effectively treated acute pain caused by a wide variety of conditions. As in our previous study, immediate release oxycodone was the most frequently prescribed opioid13 and no prescriptions were written for combination medications or codeine. While procedures often associated with moderate-to-severe postoperative pain were associated with increased opioid dispensing and consumption, on average across many types of surgery more than half of all opioids dispensed were not consumed and leftover opioid was rarely disposed of. These findings have important clinical and epidemiologic implications because this unused opioid provides a reservoir of medication available to help fuel the current epidemic of NMUPO.

In this study, opioids were the primary component of multimodal analgesic therapy and, based on parental assessment, were largely effective in treating pain. Thus, the American Pain Society’s campaign to better assess and treat pain (“the fifth vital sign”) appears to have been successful.21 Not unexpectedly, the quantity of opioid consumed by our surgical patients was associated in part with the procedures they had undergone, as patients who had undergone procedures often associated with significant postoperative pain22,23 were prescribed and consumed the most opioid doses. However, we also found that opioid over-dispensing was common in keeping with prior adult and pediatric studies.24,25 For example, Abou-Karam and colleagues previously reported that most children consumed no more than 2 doses of morphine (< 10% of doses dispensed) following hospital discharge.25 We are not surprised that our patients required more opioid doses upon discharge than they report, as we hypothesize that they often underwent more complex or painful procedures based on hospital length of stay and surgical service. Even so, more than half of the doses dispensed to our subjects remained unconsumed.

To date, most regulatory, medical, and research activity devoted to NMUPO has focused on chronic opioid use, particularly in non-cancer pain.5,6,10 Little attention has been paid to prescribing opioids for acute pain, particularly in children.11,26,27 Pediatric providers currently have few objective resources available to guide practice. Studies to fill this knowledge gap regarding actual patient needs, however, have become increasingly important in light of state and federal government attempts to address the ongoing opioid epidemic in part by limiting opioid availability.4,28

While many recent initiatives and guidelines restricting the amount of opioid dispensed to 3 or 7 days are designed for adult pain patients, future regulations could ultimately result in similar, restrictive dispensing for all patients, including children. However, we found that 52% of our patients required opioid for more than 3 days and more than one-third needed opioids for more than 1 week after discharge. Thus, we are concerned that in the absence of evidence a one-size-fits-all approach to dispensing could impede the appropriate treatment of pain experienced by pediatric patients upon hospital discharge.

Even though our results do, in fact, support more limited opioid dispensing, to what degree dispensing can be curtailed while still providing adequate analgesia is unclear. One-third of families surveyed had more than 80% of their dispensed doses remaining, but we also observed a two- to three-fold variability in number of doses consumed by individual patients across many surgical specialties. Given this variability, providers may believe that the quantities of medication they are currently prescribing are reasonable as they provide sufficient medication to the vast majority of their patients. However, if reasonable prescribing practices result in many patients receiving more opioid than will be consumed, as seen here, then safe dispensing should also include guidance regarding appropriate disposal of leftover medication. Thus, we were particularly concerned to discover that less than 5% of families disposed of leftover medication, and that most families received minimal instruction regarding how to do so. Current practices for discarding unused medications at home often involve putting them in household garbage or flushing them down the toilet,29, however, the safety and appropriateness of these recommendations are questionable.30 Further, suggestions that families return unused opioid to a police station or designated pharmacy are often impractical and not evidence-based in terms of effectiveness. While this uncertainty may contribute to inaction, failing to inform families to dispose of their leftover opioid may help create a reservoir for opioid sharing, selling, and diversion.

In this small, time-limited study, we found the amount of unconsumed opioid remaining in households totaled over 40,000 morphine mg equivalents. Given that 5 million pediatric surgeries – over 20,000 times the number reported on here – are performed annually in the United States, even if many of these children are not discharged with an opioid prescription, our findings suggest that substantial amounts of unused opioid may remain available in the community as a result of pediatric surgery. Furthermore, over half of the households in our study included adolescents (patients or siblings), a population for whom unconsumed legally prescribed opioids can provide both a primary source and gateway drug for opioid addiction.31,32 Thus, the risk of harm, both intentional (from diversion for nonmedicinal use) and unintentional (from accidental ingestion) posed by leftover opioid in the home may be compounded in the pediatric setting.

There are several limitations to this study. While our PPS provides care to both medical and surgical patients, our findings are not generalizable to all hospitalized children. Our cohort was limited to pediatric inpatients treated at a single tertiary care hospital in the northeast United States, and the vast majority of patients experienced acute pain as a result of surgery. While we believe our prescribing patterns are similar to comparable institutions, they may, in fact, not be generalizable.

Our sampling techniques may also have introduced bias. Results were obtained via telephone survey and not all families could be reached at both sampling times. Our interview completion rate was higher at two days than two weeks which we attribute in large part to increased parental presence in the home immediately following hospitalization. Given our study design, however, we could not attempt to contact families over a prolonged period of time. Our findings are, therefore, limited by the amount of missing data on the number of doses consumed. Although we do not believe that there are any systematic differences between patients with and without missing data, the proportion of missing data is significant, and this may have affected our estimates.

Even when families were available, responses may have been affected by parent/caregiver memory or unwillingness to answer all questions. While we obtained objective pain scores for children less than 7 years of age from parents, older children were often not at home at the time of the survey phone call, limiting our ability to collect their self-reported pain assessments. Hence, most assessments of pain management were made by parents and may not have accurately reflected the child’s true level of pain or satisfaction with care. This may be of particular importance because previous studies report the underestimation and under treatment of pain by parents.33

Even though our results support a preliminary recommendation that prescribing should take into account factors associated with consumption, such as pain at time of discharge and class of surgery, the relatively small sample sizes for many of the surgeries we studied precluded in-depth analysis of analgesic needs for individual procedures. In addition, other studies have demonstrated that age, sex, and race are important variables as well,34–38 However, our sample size may have been too small to detect statistically significant associations with these variables. Previous studies also suggest that language, specifically English versus Spanish, affects opioid use,39 but because English fluency was a study inclusion criteria, we are unable to verify this finding. In light of the limitations described here, we see this study as a preliminary step, highlighting the need for larger and more in-depth studies moving forward.

In conclusion, we found that in pediatric patients after hospital discharge, oral opioids effectively treated acute pain caused by a wide variety of surgical and medical conditions. However, pediatric providers frequently prescribed excess opioid and the resulting leftover opioid remained in the home after completion of therapy, providing a prescription drug reservoir potentially capable of contributing to the ongoing epidemic of NMUPO. These findings underscore the need for further research to guide future opioid prescribing guidelines that will enable physicians to provide safe and effective patient care to children experiencing acute pain.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

How much opioid is prescribed and consumed by pediatric patients to manage pain following hospital discharge, how much dispensed opioid remains left over when no longer required to treat pain, and is this excess medication appropriately disposed of?

Findings

Interviewing the parents of 343 pediatric inpatients after hospital discharge, we found that opioid consumption upon discharge was related in part to surgical procedure and pain at time of discharge; however, more than half of all doses dispensed were left unconsumed when opioid was no longer necessary to treat pain, and only 4% of families disposed of this leftover medication.

Meaning

Pediatric providers frequently prescribed more opioid than needed to treat pain following hospital discharge, and this excess prescribed opioid was rarely disposed of, providing a drug reservoir for potential drug diversion and misuse.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Funding for this study was provided by the Richard J. Traystman Endowed Chair and the Hilda and Jacob Blaustein Pain Foundation.

We would like to acknowledge support for the statistical analysis from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 1UL1TR001079.

The authors also wish to acknowledge Claire F. Levine, MS, ELS, for editing and critical review of this manuscript. No compensation was received.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Myron Yaster, MD has served as a consultant and on the data safety monitoring board for Purdue Pharma and Endo Pharmaceuticals. With the exception of Dr. Yaster there are no financial disclosures.

Author Contributions:

Dr. Yaster: This author helped conceptualize and design the study and data collection instruments, acquire data, analyze and interpret the data, draft the initial manuscript, critically review the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Monitto: This author helped conceptualize and design the study and data collection instruments, acquire data, analyze and interpret the data, draft the initial manuscript, critically review the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Mr. Hsu: This author helped conceptualize and design the study and data collection instruments, acquire data, analyze and interpret the data, draft the initial manuscript, critically review the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Yenokyan: This author helped analyze and interpret the data, draft the initial manuscript, critically review the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Roter: This author helped conceptualize and design the study and data collection instruments, draft the initial manuscript, critically review the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. Gao: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Mr. Park: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Mr. Vozzo: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. White: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. Edgeworth: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. Vasquenza: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ms. Atwater: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Shay: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. George: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Kost-Byerly: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Kattail: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Lee: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Vickers: This author helped acquire data, critically review and revise the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This data was previously presented in abstract form at the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Annual Meeting in October 2015. Abstract #1056

References

- 1.Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, et al. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. AnesthAnalg. 2003;97:534–540. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000068822.10113.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Daigle S, Mojica J, et al. Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157–164. doi: 10.2147/jpr.s7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morone NE, Weiner DK. Pain as the fifth vital sign: exposing the vital need for pain education. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1728–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauber-Schatz EK, Mack KA, Diekman ST, et al. Associations between pain clinic density and distributions of opioid pain relievers, drug-related deaths, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and neonatal abstinence syndrome in Florida. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part I--evidence assessment. Pain Physician. 2012;15:S1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2--guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15:S67–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Injury prevention and control: Prescription drug overdose. 2015 Retrieved 06/10/2017, from www.cdc.gov/drugoverddose/index.html.

- 8.Quinones S. Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz J. Drug deaths in America are rising faster than ever. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, et al. The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:557–564. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schechter NL, Walco GA. The Potential Impact on Children of the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain: Above All, Do No Harm. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miotto K, Kaufman A, Kong A, et al. Managing co-occurring substance use and pain disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:393–409. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George JA, Park PS, Hunsberger J, et al. An Analysis of 34,218 Pediatric Outpatient Controlled Substance Prescriptions. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:807–813. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers CT, Finley GA, McGrath PJ, et al. The parents’ postoperative pain measure: replication and extension to 2–6-year-old children. Pain. 2003;105:437–443. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–830. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Annals of Statistics. 2013;31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newson RB. Frequentist q-values for multiple-test procedures. The Stata Journal. 2010;10:568–584. www.stata-journal.com/sjpdf.html?articlenum=st0209. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hintze J. PASS 12. NCSS, LLC; Kaysville, UT: www.ncss.com. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell JN. The fifth vital sign revisited. Pain. 2016;157:3–4. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhly WT, Maxwell LG, Cravero JP. Pain management following the Nuss procedure: a survey of practice and review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:1134–1139. doi: 10.1111/aas.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pestieau SR, Finkel JC, Junqueira MM, et al. Prolonged perioperative infusion of low-dose ketamine does not alter opioid use after pediatric scoliosis surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24:582–590. doi: 10.1111/pan.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, et al. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. 2011;185:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abou-Karam M, Dube S, Kvann HS, et al. Parental Report of Morphine Use at Home after Pediatric Surgery. J Pediatr. 2015;167:599–604. e591–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kharasch ED, Brunt LM. Perioperative Opioids and Public Health. Anesthesiology. 2016 doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wunsch H, Wijeysundera DN, Passarella MA, et al. Opioids Prescribed After Low-Risk Surgical Procedures in the United States, 2004–2012. Jama. 2016 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.House Committee on Ways and Means TCoM; Massachusetts TtGCotCo, editor. Bill H.3944 189th (Current): An Act relative to substance use, treatment, education and prevention. 2016. p. H3944. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeng DD, Snyder RC, Medico CJ, et al. Unused medications and disposal patterns at home: Findings from a Medicare patient survey and claims data. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2016;56:41–46. e46. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glassmeyer ST, Hinchey EK, Boehme SE, et al. Disposal practices for unwanted residential medications in the United States. Environ Int. 2009;35:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman RA. The changing face of teenage drug abuse--the trend toward prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1448–1450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fortier MA, MacLaren JE, Martin SR, et al. Pediatric pain after ambulatory surgery: where’s the medication? Pediatrics. 2009;124:e588–e595. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadhasivam S, Chidambaran V, Olbrecht VA, et al. Opioid-related adverse effects in children undergoing surgery: unequal burden on younger girls with higher doses of opioids. Pain Med. 2015;16:985–997. doi: 10.1111/pme.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kozlowski LJ, Kost-Byerly S, Colantuoni E, et al. Pain prevalence, intensity, assessment and management in a hospitalized pediatric population. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng B, Dimsdale JE, Shragg GP, et al. Ethnic differences in analgesic consumption for postoperative pain. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:125–129. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimenez N, Galinkin JL. Personalizing pediatric pain medicine: using population-specific pharmacogenetics, genomics, and other -omics approaches to predict response. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:183–187. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mossey JM. Defining racial and ethnic disparities in pain management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1859–1870. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jimenez N, Seidel K, Martin LD, et al. Perioperative analgesic treatment in Latino and non-Latino pediatric patients. JHealth Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:229–236. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.