Abstract

Untreated substance use disorders remain a pervasive public health problem in the United States, especially among medically-underserved and low-income populations, with opioid and alcohol use disorders (OAUD) being of particular concern. Primary care is an underutilized resource for delivering treatment for OAUD, but little is known about the organizational capacity of community-based primary care clinics to integrate treatment for OAUD. The objective of this study was to use an organizational capacity framework to examine perceived barriers to implementing the continuum of care for OAUD in a community-based primary care organization over three time points: pre-implementation (preparation), early implementation (practice), and full implementation. Clinic administrators and medical and mental health providers from two clinics participated in interviews and focus groups. Barriers were organized by type and size, and are presented over the three time points. Although some barriers persisted, most barriers decreased over time, and respondents reported feeling more efficacious in their ability to successfully deliver OAUD treatment. Findings contribute to the needed literature on building capacity to implement OAUD treatment in primary care and suggest that while barriers may be sizable and inevitable, successful implementation is still possible.

Keywords: Substance use Treatment, Integrated Care, Primary care, Barriers, Implementation, Capacity

1. Introduction

Untreated substance use disorders remain a pervasive public health problem in the United States, especially among medically-underserved and low-income populations (Ghitza & Tai, 2014). In 2013, 90% of the 23 million Americans who needed substance use treatment reported that they did not receive it during the prior year (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Opioid and alcohol use disorders (OAUD) are of particular concern, with an estimated 15.1 million individuals in the U.S. suffering from an alcohol use disorder (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015a) and an estimated 4.8 million abusing opioids (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015b). Alcohol is implicated in nearly one-third of emergency department admissions (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011), and the majority of overdoses resulting in death are from opioid misuse, which is now a leading cause of unintentional death in the United States (Kirschner, Ginsburg, & Sulmasy, 2014). Patients with substance use disorders utilize heath care services more often than patients without (Blose & Holder, 1991; Goodman, Holder, & Nishiura, 1991; Goodman, Holder, Nishiura, & Hankin, 1992; Holder & Blose, 1986, 1991, 1992; Holder & Hallan, 1986; Lennox, Scott-Lennox, & Holder, 1992; Parthasarathy, Mertens, Moore, & Weisner, 2003; Parthasarathy, Weisner, Hu, & Moore, 2001; Reiff, Griffiths, Forsythe, & Sherman, 1981) and have a higher prevalence of medical and mental health conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic liver disease, various cancers, depression, anxiety disorders, and major psychosis (Chou, Grant, & Dawson, 1996; Ghitza, Wu, & Tai, 2013; Mertens, Lu, Parthasarathy, Moore, & Weisner, 2003; Sikkink & Fleming, 1992; Stein, 1999). However, despite the high comorbidity of substance use disorders and medical disorders, substance use treatment is rarely integrated within the context of medical care (Parthasarathy et al., 2003; Sacks et al., 2016; Teruya & Urada, 2014; Urada, Teruya, Gelberg, & Rawson, 2014).

Although substance use treatment delivered in specialty care programs plays an important role for patients with severe disorders, limited availability, long waitlists, and stigma mean that a disproportionate number of patients fail to receive treatment. Primary care might be able to help fill the gap by offering an important and underutilized resource for delivering substance use treatment for patients across the spectrum of mild to severe disorders. Effective treatments such as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and evidenced-based psychotherapeutic approaches such as motivational interviewing-based interventions (Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Miller & Rose, 2009) are available and appropriate for delivery in primary care settings, yet only a small proportion of individuals with OAUDs receive these treatments (Blanco et al., 2015; Blanco et al., 2013; Compton, Thomas, Stinson, & Grant, 2007; Grella, Karno, Warda, Moore, & Niv, 2009; Hasin, Stinson, Ogburn, & Grant, 2007; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). Effective integration of OAUD treatment into primary care settings could increase access to treatment for many individuals with OAUDs. However, in order for OAUD treatment to be adopted and integrated within existing practices, organizations must have the capacity to deliver the treatment (Meyer, Davis, & Mays, 2012; Ober et al., 2015; Watkins et al., 2017).

Organizational capacity is considered critical in determining how well an organization or system performs and is able to adopt new practices (Brown, LaFond, & Macintyre, 2001; Hall et al., 2003; LaFond, Brown, & Macintyre, 2002; Meyer et al., 2012; Mizrahi, 2004). According to Meyer et al. (2012), there are eight dimensions of organizational capacity: fiscal and economic resources, workforce and human resources, physical infrastructure, inter-organizational relationships, data and informational resources, system boundaries and size, governance and decision-making structure, and organizational culture. Although a number of studies have examined capacity barriers to integrating substance use treatment into primary care (Amaral-Sabadini, Saitz, & Souza-Formigoni, 2010; Barry et al., 2009; DeFlavio, Rolin, Nordstrom, & Kazal, 2015; Quest, Merrill, Roll, Saxon, & Rosenblatt, 2012; Urada et al., 2014; Walley et al., 2008), these studies examined barriers at a specific point in time and did not examine how barriers might change over the course of implementation. In addition, these studies did not systematically examine barriers using an organizational capacity framework. Using such a framework is important to identify the range of resources necessary to support change. Because barriers are likely to be dynamic and related to the phase of implementation (e.g., physical infrastructure barriers may become more salient when the new practice is implemented, rather than when the new practice is being prepared for), it is important to look at how perceptions of capacity requirements and barriers change over time. Further, implementation theories suggest that factors that support implementation vary across the different phases of implementation (Aarons, Hurlburt, & Horwitz, 2011; Kilbourne, Neumann, Pincus, Bauer, & Stall, 2007; Simpson & Flynn, 2007); it stands to reason that barriers to implementation also differ by phase.

To address these gaps in the empirical literature, the current study used Meyer’s organizational capacity framework to 1) identify and categorize perceived capacity barriers to integrating OAUD care in two primary care clinics within a federally qualified health center (FQHC); 2) rate the size of barriers in terms of the frequency with which they were mentioned; and 3) assess the degree to which perceptions of these barriers changed during three distinct phases of implementation. The three phases were preparation, practice, and full implementation, phases that are conceptually consistent with implementation phases described in the literature (Aarons et al., 2011; Kilbourne et al., 2007; Simpson & Flynn, 2007). The preparation phase refers to the period spent preparing for implementation and includes increased awareness and recognition of the improved approach to address an organizational challenge; the practice phase refers to the period when an organization identifies and pilots new practices to implement in their setting; and the full implementation phase refers to the period when an organization fully implements the new practices.

2. Methods

2.1 Study Setting and Context

This study was conducted at two community-based primary health care clinics that were part of a FQHC. The two clinics provided primary care services to over 22,000 low-income residents of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Patients were racially and ethnically diverse, with 58% identifying as Latino/a, 26% identifying as White/Caucasian, 11% identifying as Black/African American, and 4% identifying as Asian.

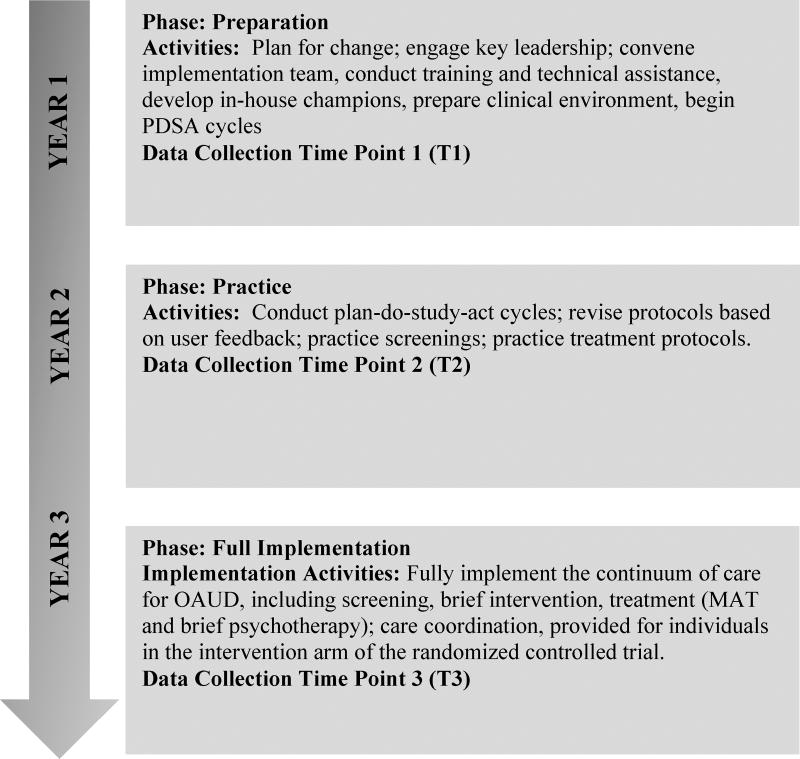

The examination of capacity and barriers occurred as part of a larger study of the effectiveness of collaborative care for OAUD in primary care. Collaborative care for OAUD was a system-level clinical intervention that used care coordinators and a patient registry to support the delivery of medication-assisted treatment and/or a six-session motivational interviewing- and cognitive therapy- based brief treatment (Ober et al., 2015; Rollnick & Miller, 1991; Watkins et al., In press; Watkins et al., 2017). In the current study, implementation refers to the process of integrating the continuum of care for OAUD using collaborative care into the two primary care clinics, including screening, brief intervention, MAT, and brief therapy. In the preparation phase (9/2012-9/2013; T1 data collection 9/2012-1/2013), researchers and clinic staff collaborated to set goals, identify barriers and facilitators, and develop clinical procedures related to screening and treatment delivery. During the practice phase (9/2013-6/2014; T2 data collection 12/2013-3/2014), the clinic tried out the various clinical procedures, conducting plan-do-study-act cycles with key staff to select among the options. Finally, during the full implementation phase (6/2015-1/2016; T3 data collection 10/2015-1/2016), the clinic fully activated the continuum of care for OAUD, and the researchers conducted a randomized controlled trial in which patients were randomly assigned to receive collaborative care-based OAUD treatment or services as usual. Study phases and activities are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Implementation Timeline

2.2 Participants and Procedures

Clinic administrators participated in one-on-one in-person interviews while medical and mental health providers participated in focus groups to discuss anticipated barriers and/or experienced capacity barriers to integrating comprehensive OAUD treatment. All participants were recruited through email and announcements at staff meetings. Administrators also received a follow-up telephone call for scheduling purposes. Focus groups were held during regular staff meeting times. Participation was voluntary. Data collection took place over a 3–4 month period at each time point.

For both the focus groups and the interviews, we developed a semi-structured protocol guide that asked “grand tour” questions related to the continuum of care for OAUD, including screening; MAT; psychotherapy and collaborative care. Specific probes were used to solicit more detailed responses about barriers to implementation. For each aspect of the continuum of care, we developed questions designed to elicit responses about the perceived appropriateness, acceptability, and feasibility of the practice, and intentions to adopt the practices. These are implementation outcomes recommended by Proctor et al., (2011) that, based on organizational change theories, are thought to be critical precursors of the adoption of new practices (Bandura, 1977). For example, within the perceived ‘acceptability’ category, we asked, “How would you describe the attitudes of the staff at VFC towards providing substance use disorder treatment to patients with substance use disorders? By substance use treatment I mean any kind of treatment, including counseling with a therapist or other counselor, a brief intervention by a physician, or medication that is prescribed by a physician.” Within the ‘adoption’ category, we asked during the preparation phase questions such as, “What are the potential barriers to VFC adopting MAT for people with an opiate or alcohol disorder?” Probes included: “Billing/insurance barriers? Documentation barriers, such as restrictions on sharing substance use information across providers? Certification of providers? Training providers? Patient willingness? Provider willingness? Specific policies? During the practice and implementation phases we asked, “Have there been any barriers so far to VFC adopting MAT for patients with an opiate or alcohol disorder? What are these barriers? Probes were the same across time points. To better understand barriers to adoption of collaborative care, we asked questions such as, “Do you think that having Care Coordinators to help coordinate patient care with therapists and medical providers is effective? Probes included: How could care coordination be improved?” Interviews and focus groups were repeated across the three different implementation phases. We asked the same questions across time points, with slight variations to adjust for greater knowledge in the practice and implementation phases than in the preparation phase. All staff types received questions about MAT, psychotherapy and collaborative care. All interviews and focus groups were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy of terminology and for completeness. Protocols were reviewed by the project Steering Committee, which included the research team and research partners from VFC. The study protocol and all study procedures were approved by the principal investigator’s institutional review board. While the majority of respondents participated in all three phases, staff turnover meant that the three groups of respondents were not identical. All interview and focus group data were included in the analyses, regardless of phase, to generate the maximum amount of data. Focus groups were conducted by RAND survey research group professional qualitative interviewers. The research team reviewed the protocols with interviewers. All interviews and focus groups were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for completeness.

2.3 Analytic Framework

The analysis utilized Meyer’s (2012) organizational capacity framework to categorize barriers to implementation. The framework consists of eight constructs, which are presented with examples in Table 1.

Table 1.

Meyer’s Organizational Capacity Framework

| Construct | Examples |

|---|---|

| Fiscal and economic resources | Budgeting, sources of revenue, and cost of running the program |

| Workforce and human resources | Number of employees, staff knowledge/skills/expertise, and training |

| Physical infrastructure | Office space and equipment |

| Inter-organizational relationships | The density and strength of relationships, collaboration, competition, and communication |

| Data and informational resources | Databases, registries, and IT support |

| System boundaries and size | Community attributes, population density, and demographics (ethnicity, poverty, and insured/uninsured) |

| Governance and decision making | Legal authorities, governance structure, and policies, procedures, and guidelines |

| Organizational culture | The mission, values, and leadership of the organization |

2.4 Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using directed content analysis (Potter & Levine-Donnerstein, 1999) nested within a framework approach (Smith & Firth, 2011). Transcribed interviews and focus groups were reviewed to identify primary themes, which were then categorized into one of the eight capacity constructs in accordance with the Meyer (2012) framework using the qualitative analysis software program Dedoose version 7.0.23 (Dedoose, 2016). Within each primary theme, specific capacity barriers were identified from the data guided, in-part, by Meyers (2012) framework. For example, within the construct “Fiscal and Economic Resources,” a theme that emerged was “Billing and Cost of Service” and a barrier within that theme was “reimbursement.” Three study investigators (EDS, AJO, SBH) reviewed the transcripts and created a formal codebook that was organized by the eight constructs, and themes for each construct as well as specific capacity barriers were then identified from reviewing the data.

The coding team refined the codebook until all agreed that all identified primary themes and barriers were included. Transcripts were then coded separately by two trained research assistants, and 3 transcripts (10%) were randomly selected and independently double-coded. A study investigator assessed both coded versions of these transcripts, and inter-rater discrepancies were identified, discussed, recoded, and inter-rater reliability was recalculated until adequate inter-rater agreement (k = 73.7) was achieved between coders based on consistency. Once all barrier themes were identified and agreed upon by the investigative team, the content within each theme was coded once again based on the specific barriers mentioned that constituted that theme. We obtained frequencies for each barrier by tallying the total number of transcripts in which each barrier was mentioned at least once. These frequencies were a proxy for barrier size and only those instances were counted in which the valence of the quotation was perceived to be negative. Instances in which barriers were mentioned in the context of being resolved or no longer perceived as a barrier were not counted in frequency tallies (Buetow, 2010). Focus group transcripts were counted as the equivalent of a single interview transcript, as we were unable to identify and quantify disparate respondents within each focus group transcript. Once frequencies for each barrier were obtained we divided barriers into: 0% = the barrier wasn’t mentioned; 1–25% = small barrier (i.e., the barrier was mentioned in 1–25% of the transcripts); 26–50%, “small-to-medium” barrier; 51–75% = “medium-to-large” barrier; and 76–100% = large barrier.

Consistent with community participatory research best practices (Israel et al., 2008), we presented the themes and frequencies identified by the coding process to a sub-sample (n = 6) of the original interview and focus group participants who had participated in all three phases of data collection (i.e., 3 administrators, 2 medical providers, and 1 mental health provider) for validation of findings approximately one year after the end of data collection. Participants were shown a visual representation of the size of each barrier at each of the three phases and asked if they agreed with the barrier size and direction of change across time. If participants disagreed with a barrier’s size at any phase, they were asked to provide reasons. This approach to directed content analysis is consistent with the method of saliency analysis (Buetow, 2010) where barrier size was determined based on both the proportion of transcripts in which the barrier was mentioned combined with the perceived ‘importance’ of the barrier based on participant ratings of barrier size at each time point.

3. Results

3.1 Characteristics of Participants

Characteristics of study participants are presented in Table 2. The average age of participants was 44, and participants were mostly female (84%) and Hispanic (70%). More than half (52%) had been in their current position at the clinic for more than 10 years. Administrators at each time point included the chief medical officer (a different person at each time point), and chief executive officer, chief operating officer, director of mental health, the head nurse at each clinic, the supervisor of clinic coordinators, and the front desk and security supervisors, all of whom were the same people at each time point. The medical provider focus groups included 9 medical providers at T1 and T2, and 10 at T3; the mental health focus groups included 8 mental health providers at each time point. “

Table 2.

Participants by Position

| Respondent Type | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Provider Focus Group | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Mental Health Provider Focus Group | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Administrators | |||

| Chief Executive Officer | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chief Medical Officer | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Director of Mental Health | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Front Desk Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Care Coordinator Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Security Supervisor | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Head of Nursing Staff | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Associate Chief Medical Officer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Chief Operating Officer | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Note: T1 = preparation phase; T2 = practice phase, T3 = full implementation phase; total medical provider focus group participants: T1 = 9, T2 = 9, T3 = 10, total mental health provider focus group participants: T1 = 8, T2 = 8, T3 = 8. The number of focus groups varied by time point due to randomization of medical providers and focus groups into two study conditions after T1. Medical providers did not remain randomized after the practice phase due to patient concerns about switching providers, so they returned to a single focus group in T3. Mental health providers remained randomized and had an additional focus group to accommodate providers’ schedules.

3.2 Overview of Qualitative Results

Qualitative content analyses revealed 17 themes and 34 specific barriers within Meyer’s (2012) eight-construct organizational capacity framework. Barriers and subthemes, and the frequency with which they were mentioned at each phase, are presented in Table 3. Those that were expressed to be of at least “small-to-medium” size at one or more phases during the study are described with an illustrative quote. During the validation meeting, participants agreed with the size of 95.4% of the barriers based on our frequency tallies for each phase. Where there was disagreement, the frequency ratings reported in the Table were retained but the size ratings (i.e., the color codes) were adjusted according to the validation meeting feedback. Adjustments are indicated by an asterisk in Table 3.

Table 3.

Changes in organizational capacity barriers to implementing the continuum of care for opioid and alcohol use disorders across implementation phases

| Construct | Theme | Barrier | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |||

| Fiscal and Economic Resources | Billing/Cost of Service | Reimbursement for Services | 45 | 14 | 14 |

| Medication Reimbursement | 78 | 57 | 71 | ||

| Funding Additional Staff | 44 | 29 | 50 | ||

| Insurance Barriers | 44 | 29 | 57* | ||

| Funding Stability | 33 | 43 | 50 | ||

|

| |||||

| Time | Time to Commit to Treating OAUD Patients | 89 | 86 | 86 | |

| Time for Paperwork | 11 | 21 | 7 | ||

| Wait for Appointment Times | 0 | 43 | 57 | ||

|

| |||||

| Workforce and Human Resources | Motivation | Providers Lacking Motivation | 56* | 57 | 29 |

|

| |||||

| Self-Efficacy | Providers Not Feeling Knowledgeable | 67 | 50 | 43 | |

|

| |||||

| Training | Worry that Training will not be enough | 78 | 82 | 86* | |

|

| |||||

| Staff Configuration | Specialty Clinic | 33 | 21 | 14 | |

| Dedicated Provider | 89 | 29 | 50 | ||

|

| |||||

| Quantity of Staff | Lack of Staff | 89 | 57 | 43 | |

| Staff Turnover/Training | 78 | 29 | 14 | ||

|

| |||||

| Physical Infrastructure | Physical Space | Need for More Clinic Space | 33 | 37 | 14* |

| Distance Between Providers | 22 | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Equipment/Supplies | Not Having Enough Medication | 56 | 14 | 14 | |

| Equipment Problems | 0 | 7 | 14 | ||

|

| |||||

| Intra/Inter-organizational Relationships | Administration-Clinic Staff Collaboration | Need for Better Communication within Clinic | 44 | 42 | 39 |

|

| |||||

| Need for Referral Network | Availability of Specialty OAUD Clinics and Providers | 56 | 29 | 21 | |

|

| |||||

| Data and Informational Resources | Electronic Health Record | Problems with Appointment Reminders | 11 | 14 | 36 |

| Difficulty with Registry Integration | 0 | 43 | 57 | ||

|

| |||||

| System Boundaries and Size | Clinic Location and Attributes | Clinic Hours | 0 | 21 | 14 |

| Clinic Not Appropriate Setting for OAUD Patients | 33 | 43 | 21 | ||

|

| |||||

| Population Demographics | Large Homeless Population | 55 | 43 | 43 | |

| Many Patients with Comorbidities | 67 | 43 | 43 | ||

| Fear of Attracting Too Many OAUD Patients | 67 | 29 | 29 | ||

| Fear of Not Treating Enough OAUD Patients | 22 | 50 | 29 | ||

|

| |||||

| Governance and Decision-Making Structure | Policies and Procedures | State/County Policies | 11 | 12 | 14 |

| Clinic Policies | 78 | 57 | 57 | ||

| Lack of Policy Regarding OAUD Treatment | 33 | 14 | 14 | ||

|

| |||||

| Organizational Culture | Fit with Mission Values | Alternative Treatment Model Would be Better Fit | 11 | 14 | 0 |

|

| |||||

| Leadership | Fear Leadership will not ensure OAUD Treatment | 33 | 14 | 14 | |

No Barrier=0

No Barrier=0

Small Barrier=1–25%

Small Barrier=1–25%

Small-to-Medium Barrier=26–50%

Small-to-Medium Barrier=26–50%

Medium-to-Large Barrier=51–75%

Medium-to-Large Barrier=51–75%

Large Barrier=76–100%

Large Barrier=76–100%

Barrier color adjusted based on feedback from providers; percentage reflects original size. Note: T1 = preparation time point; T2 = practice time point, T3 = full implementation time point.

3.3 Constructs, Themes, and Barriers

Construct 1: Fiscal and Economic Resources

We identified eight barriers within this construct, which clustered around two themes: billing/cost of service and time.

Theme: Billing/Cost of Services

We identified five barriers related to this theme: reimbursement for services, funding for medications, funding additional staff, insurance authorization, and funding stability. Only one of these, funding for medications, was identified as a “large” barrier at T1. The other four were perceived to be “small-to-medium” at T1.

While concern about medication reimbursement was reduced over time, this remained a “medium-to-large” barrier at both T2 and T3, even though the medication for alcohol dependence, extended-release injectable naltrexone (XR-NTX), was provided for free to study patients with an alcohol use disorder. Both initially and over time, participants raised concerns about what would happen when the study ended and the medication was no longer available:

“We can’t afford to buy this medicine [XR-NTX]. We have pretty longstanding policies if we’re going to put someone on a medicine that’s viewed as a chronic disease medicine that they’re going to be taking it a long time, we need to have a steady supply for free for them so that we just don’t have to say, “Well, you can’t be on the medicine anymore because we don’t have it.” (medical provider, T1)

Once providers had experience with delivering the medication, concerns about funding lessened somewhat:

“Well these medications are costly, you know, of course we have to be mindful of that, but it works and so we are going to keep it.” (medical provider, T2)

Three billing/cost of service barriers—funding additional staff, insurance authorization, and funding stability—were “small-to-medium” at all three phases of the study. Staff funding concerns focused on whether sufficient funding would be available after the study to provide care coordination (as funding for care coordinators was provided as part of the study). Insurance authorization concerns pertained to the need to get prior authorization from insurance companies for medications and the difficulties with same-day approval of medical and mental health visits from public health care insurance plans.

Mental health providers expressed “small-to-medium” concern at T1 about reimbursement for psychotherapy services because their funding structure limited mental health services to patients with a primary mental health diagnosis. Over time, program staff was able to develop other funding streams, and the size of this barrier decreased to small by T3. This barrier was not mentioned by medical providers or administrators as only mental health providers encountered this barrier.

Theme: Time

Three time-related barriers were noted. The first of these, focusing on the amount of extra time required to treat OAUD patients, was perceived as a “large” barrier across all study phases:

“Time is such a critical factor in every encounter that anything that increases the time is going to be more difficult to get compliance with.” (medical provider, T1)

Concerns about long wait-times for appointments (both medical and mental health) was not of concern at T1 but grew to a “small-medium” concern by T2 and a medium-large concern by the end of the study:

“I think that it would be to the point where, either people are going to have to wait long times to see their [medical] provider and by then maybe we’ve done some kind of motivational intervention with them and by the time they get an appointment, they’re no longer interested. So it has to be kind of you know, one follows the other, because if there’s too much gap in between, you may lose that.” (mental health provider, T2) “Sometimes it takes 2 to 3 weeks to get that first mental health appointment and the patient is interested and wants to sign up but it takes too long and they lose interest.” (administrator, T3)

Finally, the time required for additional paperwork was mentioned as a small barrier that persisted across all three time points.

Construct 2: Workforce and Human Resources

We identified seven barriers within this construct, which were clustered within five themes: motivation, self-efficacy, training, staff configuration, and quantity of staff. Five of the seven barriers in this construct were perceived as large at T1, though all of these concerns decreased over time.

Theme: Motivation

A large concern (originally coded as “medium-to-large” but adjusted after the validation meeting to reflect consensus that this was a “large” barrier) during the preparation phase was whether providers were motivated to offer MAT.

“Some doctors aren’t even interested in certifying [obtaining the Drug Enforcement Agency waiver needed to prescribe BUP/NX]… I think you might need more buy-in from them. And find out what’s the deal there?” (administrator, T1)

By T3, these concerns were “small-to-medium”:

“[There is] always initial resistance to learning something new that’s uncomfortable. My resistance was that it [motivational interviewing] just wasn’t the way I talk or think. It’s very different so we really had a lot to learn. But now I use it all the time with all my patients.” (mental health provider, T3)

Theme: Self-Efficacy

Lack of knowledge about how to deliver the OAUD treatments (both medication and psychotherapy) initially was a “medium-to-large” barrier but decreased to “small to medium” over time:

“I think it’s because we weren’t trained to prescribe these medications. We don’t have the experience. There may be the fear of maybe doing more harm.” (medical provider, T1) “We need to have a lot of training to prescribe and treat. I feel more confident but I can see that maybe some people would not feel comfortable, even with training.” (medical provider, T3)

Theme: Training

Participants also initially expressed concern about not having the technical skill or training to offer OAUD treatment, particularly with regard to MAT. This was perceived to be a large barrier at T1 and T2, and, although somewhat smaller by T3 (after being adjusted to reflect consensus from the final provider focus group), remained a “medium-to-large” barrier in the full implementation phase:

“This is a chronic condition and you don’t know what to expect, how to adjust the medication, what kinds of complications you’ll have down the road, the relapsing, it’s just so complex. That’s why I think, this would require more of a mini-fellowship or a fellowship model in order to truly give a provider comfort that they’re going to be able to do it right and know what to expect.” (medical provider, T1)

“I think [the key] is ongoing training, and even if it’s just 10, 15 minute little training snippets at provider meetings, I think, the more we hear it, or the more therapists hear it, see it, touch it, feel it, see it in practice, I think it kind of, becomes integrated.” (mental health provider, T3)

Theme: Staff Configuration

A large barrier related to this theme in the preparation phase was the perceived need for a dedicated OAUD provider. This barrier became smaller over the course of the study and was “small-to-medium” at T3:

“It would be better to have a dedicated provider then you could just refer [OAUD patients] to, so that providers can move on with all the other regular stuff that they have to do.” (medical provider, T1)

Another staffing configuration barrier, the need for a specialty OAUD clinic, was a “small-to-medium” barrier at T1; several providers suggested that, instead of training all providers, OAUD treatment should be offered in a specialty OAUD clinic housed within the organization. By T3, this option was not mentioned.

Theme: Quantity of Staff

Two staffing barriers—concerns about a general lack of sufficient staff as well as staff turnover and the need for ongoing training of new staff—were initially considered to be large barriers of size:

“We recently lost 5 physicians and I think we have only hired one provider, so we’re still short 4, so that would have to be our biggest barrier at this point because we are unable to meet the demand of clients that we have. To add a new program just means we cannot treat people who have colds or hypertension because we are now going to treat substance abuse.” (administrator, T1)

“There is a whole set of patients here that have no regular primary care doctor at all. They see whatever resident is available. The residents are always changing rotation so [the residents] need ongoing training to deliver OAUD treatment.” (administrator, T1)

The size of both staffing barriers decreased over time, with turnover and training concerns in particular becoming a small barrier by T3.

Construct 3. Physical Infrastructure

We identified four barriers falling into two themes for this category: physical space and equipment/supplies.

Theme: Physical Space

Concern over the need for more physical space was perceived to be a “small-to-medium” barrier across all phases of the study, after adjusting barrier size for feedback we received during data validation. That is, providers in the final focus groups thought that size had remained a small-to-medium barrier at T3. However, providing distance between providers for confidential OAUD screening was considered a small barrier at T1 and was not mentioned again as providers were able to use confidential exam rooms for screening when more privacy was desired.

Theme: Equipment/Supplies

Concern about not having enough medication on site was perceived as “medium-to-large” during the preparation phase but then decreased to a small barrier over time. One administrator commented at T3:

“Well, here at this site we didn’t have a pharmacist and a couple of—just a couple of times we had to send somebody over to a different site to get the medication because we ran out.”

Equipment problems was mentioned as a small barrier to implementation across the T2 and T3 study phases.

Construct 4. Intra-organizational and Inter-organizational Relationships

We identified two barriers in this construct, which corresponded to two themes: administration and clinic staff collaboration and need for a referral network.

Theme: Administration and Clinic Staff Collaboration

The need for better communication between front-line staff, providers and program leadership was mentioned as a “small-to-medium” barrier across all study phases.

Theme: Need for Referral Network

Concerns around the availability of more intensive rehabilitation services was a “medium-to-large” barrier but decreased in size over the study phases:

“I’m thinking if somebody needed inpatient care, are we going to need to find a place or have the resources to send them to an inpatient care facility for detox before they start on our program.” (administrator, T1)

Construct 5. Data and Informational Resources

We found two types of barriers associated with the electronic health record.

Theme: Electronic Health Record

Difficulty with registry integration was a small barrier during the preparation phase but increased to “medium-to-large” during the full implementation phase:

“I wish the registry was added to NextGen (the practice management system), that way whenever the coordinators are scheduling the follow-up appointment for the patient we can also schedule injection [of XR-NTX].” [Reflecting the desire for all information about OAUD program participants to be located in one place.] (administrator, T3).

Problems with OAUD patient appointment reminders was perceived as a small barrier at the preparation and practice phases and increased to “small-to-medium” size during the full implementation phase.

Construct 6. System Boundaries and Size

We identified six barriers in this construct, which were related to two themes: clinic location/attributes and population demographics.

Theme: Clinic Location and Attributes

There were two barriers related to this theme. Clinic hours or the ability to see substance use disorder patients outside of standard clinic hours was viewed as a “small” barrier by participants during all three study phases as the perception was that clinic hours, while less than ideal, were fine for most patients. The perception that the clinic was not an appropriate setting for OAUD patients due to being a “family clinic” in which pediatric patients are also seen was perceived as “small to medium” at the first and second phases of the study and decreased in size over time.

Theme: Population Demographics

The first three barriers related to this theme were: treating a significant homeless population, treating many patients with mental health comorbidities, fear of attracting too many OAUD patients. These were “medium-to-large” during the preparation phase and decreased to “small-to-medium” by the full implementation phase:

“The challenge there is they’re a homeless population so a lot of times, they don’t have phone numbers. So how do you follow up? And yeah, it’s very difficult.” (mental health provider, T1)

“If we start giving these meds (referring to BUP/NX) here we’ll see all these people from across town hear about it and start coming to the clinic.” (medical provider, T1)

“I think for both the medications also just so many of our patients have really severe mental health issues that we wouldn’t feel comfortable or disqualifies them [from OAUD treatment].” (medical provider, T2)

The barrier fear of not treating enough OAUD patients to keep skills up was small at T1, increased to a “small-to-medium” concern by T2, and then decreased at T3:

“If we had more volume we’d have more experience with it, but if we do like one every couple months or something like that, then we feel like we won’t keep our skills up.” (medical provider, T2)

Conversely, the fourth barrier in this theme was: fear of not treating enough OAUD patients to keep skills up. This barrier was perceived to be small at T1 but increased in size to small-to-medium in T2 and T3.

Construct 7. Governance and Decision Making Structure

We identified three barriers related to the theme of policies and procedures.

Theme: Policies and Procedures

One of these barriers—related to clinic policies— was large during the preparation phase. Clinic policies specifically forbade the storage of narcotics (including BUP/NX) at the onsite pharmacy, and patient documentation requirements were reported as large barriers during the preparation phase and continued to be “medium-to-large” over the course of the study:

“The clinic requirement is that the patient brings proof of income and address, and if they don’t bring their proof of income and address, they normally wouldn’t get their medication. For many years we have had a no narcotic policy that shelters us from folks coming in demanding various substances. [I’m] not sure how this program will work with these policies.” (administrator, T2)

The other two policy barriers were of smaller concern. County, state, and federal policies were perceived to impact participants’ ability to deliver substance use disorder treatment at the clinic. For example, at the time of the study there were limitations on nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants ability to prescribe BUP/NX. However, these barriers were considered to be small across all phases. The lack of policy regarding how to deliver OAUD treatment was a “small-to-medium” barrier at T1, and decreased to a “small” barrier by T2, as the clinic developed written policies and treatment protocols.

Construct 8. Organizational Culture

We identified two barriers related to this construct, one related to the theme of the fit with mission values, and the other related to the theme of leadership.

Theme: Fit with Mission Values

A minority of interviews and focus groups at T1 stated that offering MAT, in particular, may not be a good fit for the clinic and that offering a more behaviorally focused intervention like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous may be fit better with the mission and goals of the clinic. However this barrier remained small across all phases.

Theme: Leadership

Concern that leadership may not fully support the provision of OAUD treatment or enforce accountability of treatment practices was reported as a “small-to-medium” barrier during the preparation phase and decreased over time.

4. Discussion

This study examined perceived barriers to implementing the continuum of care for OAUD in two community-based primary care clinics and assessed whether these barriers persisted or changed over three distinct implementation phases. We used Meyer et al.’s (2012) organizational capacity framework to categorize the themes and barriers that emerged from interviews and focus groups with clinic administrators and providers throughout the different phases of the study. We identified the size of the barriers by examining the frequency with which the barrier was mentioned, and examined how size changed with the phase of implementation. Overall, we found that, despite having identified many barriers in the preparation phase, the largest barriers decreased in size by the full implementation phase. Nevertheless, some of the largest barriers persisted through all three phases and a couple that were modest (i.e., small or “small-to-medium”) in the preparation phase increased in size by the implementation phase. The remainder of the barriers began as modest and either remained unchanged or decreased in size. In our discussion below, we first focus on barriers that remained highly salient (i.e., “medium-to-large” or large) or became highly salient by the implementation phase, as these persistent barriers might be of greatest concern to those wishing to implement OAUD treatment in primary care. We next discuss barriers that decreased in size, and last discuss barriers that remained “small-to-medium” throughout all three phases.

The largest and most persistent barriers were four barriers related to fiscal and economic resources, workforce and human resources, and governance and decision-making structure: not having enough time to treat OAUD patients, medication reimbursement, concerns about ongoing training, and clinic policies with regard to SUD treatment. The only barrier that remained large through all three phases was the additional time required for medical providers to treat OAUD patients. Indeed, during the data validation, this was discussed as both the most salient and most persistent barrier to implementation and reflects the fact that providers in community-based primary care clinics often face large workloads and an imbalance between time and increasing job demands (Linzer et al., 2001; Shanafelt, Dyrbye, West, & Sinsky, 2016; Shaw et al., 2013). Concerns about medication reimbursement began as large in the preparation phase and, although it decreased in size over time, it remained salient at the “medium-to-large” level. Concerns about accessibility of patient reimbursement for BUP/NX in particular may have become less of a concern because during the study period the treatment authorization request requirement for reimbursement through Medi-Cal was lifted for BUP/NX. However, concerns about reimbursement for XR-NTX may have been driving the persistence in size of this barrier because, with the exception of patients involved with the criminal justice system, FQHCs’ cannot currently receive fee-for-service reimbursement from California’s Medicaid program (Medi-Cal) for this medication. When we presented these data to providers for validation they agreed with the change in barrier size but underscored the fact that reimbursement for XR-NTX through Medi-Cal remains a strong concern.

Concerns about the sufficiency of training remained salient through all phases, and were “medium-to-large” during the full implementation phase, although during the validation meeting key administrative and clinical staff reported that this concern had decreased over time. Finally, barriers in the construct of governance and decision-making – specifically about the potential conflict between current clinic policies and the practice of OAUD treatment, also remained salient through the full implementation phase. These concerns pertained to the clinic pharmacy’s policy prohibiting storing narcotics and about whether the documentation required to treat patients with MAT fit with clinic policies. Although BUP/NX was fairly easily obtained through local pharmacies, it is possible that prescribing narcotics, at lease for some providers, still seemed at odds with clinic policies.

Two barriers that were not perceived to exist during the preparation phase – the long wait for appointment times and difficulty integrating the OAUD patient registry into the clinic electronic health record emerged as a small-to-medium barrier during the practice phase and increased in size to be perceived as “medium-to-large” barriers in the full implementation phase. The increase in size speaks to the practicalities of real-world implementation, some of which can’t be known prior to practice or implementation and perhaps to the challenges inherent in the use of electronic health information systems.

Barriers that began as “medium-to-large” or large, that attenuated to a “small-to-medium” barrier fell into two constructs—workforce and human resources and system boundaries and size. Within the workforce and human resources construct, concerns around staffing (having adequate staffing, staff turnover, and the need to have a dedicated provider for MAT), as well as those about providers’ self-efficacy and motivation to treat patients with OAUD, began as highly salient but attenuated by the full implementation phase. For both of these constructs, starting to provide SUD services to patients, experiencing the actual work flow, and practicing may have led to the realization that additional staff were not needed and to increased self-efficacy and motivation. In the system boundaries and size constructs, concerns that lessened over time pertained to worries about the clinic being unable to meet the psychosocial needs of OAUD patients and concern that the clinic would experience an influx of those in need of OAUD treatment that would exceed its capacity. The fact that most of the largest barriers attenuated over time is important. Clinics or practices considering integrating the continuum of care for OAUD might be hesitant due to the number of barriers they perceive during the preparation phase. Recognizing that many perceived barriers will lessen over time might provide reassurance about the possibility of change. Indeed, implementation research suggests that providers’ ability to visualize how new practices fit with the current workflow can improve willingness and motivation and, ultimately, implementation (Weiner, Lewis, & Linnan, 2009). Observing provider champions, having specific protocols and treating their own patients may have helped increase motivation and reduced the size of some barriers.

Although most barriers did decrease in size, it is important to note that some “small-to-medium” barriers in the preparation phase persisted through the full implementation phase. Three of these barriers pertained to billing and cost of services, one was about the need for more space in the clinic, one referred to the need for better communication between care coordinators, therapists and medical providers about OAUD patients, and the last was the concern that providers might not see enough OAUD patients in their practice to maintain their skills and efficacy. Although these barriers never were perceived as large, their persistence suggests that practicing and implementing OAUD treatment may not be enough to address these problems, and that focused quality improvement endeavors and policy changes may be needed to address them.

4.1 Limitations

The current study has several limitations. We could not interview every provider individually and instead interviewed key administrative staff individually and the medical and behavioral health providers in group settings. The responses from the providers may have been influenced by the group setting. We do not have a strict count of the number of people who reported/agreed with particular responses/themes. This study assessed barrier size based on the number of times each was mentioned. While interviews and focus groups were facilitated according to a structured protocol, salience could vary by type of provider, and, in some cases, the number of interviews or focus groups by provider type varied by time point. Further, quotations from focus groups were not linked to individual participants and therefore it is not possible to link specific statements from these transcripts to individual participants or provider types or to tally the number of unique participants who mentioned a barrier. Indeed, prior literature suggests that agency role can be a factor in differing views in organizational functioning (Bowles, Louw, & Myers, 2011; Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002). The analysis of change in barrier size was based on a sample of two primary care clinics nested within FQHC in West Los Angeles limiting the generalizability of these findings. Further, due to staff turnover across time, it was not possible to interview all of the same participants at all three time points. Data validation occurred retrospectively, after all time points, rather than after each individual time point which may limit study validity. Finally, although change in barrier size was documented by quantifying qualitative data, the statistical significance of these changes cannot be ascertained.

5. Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that several barriers will be present to varying degrees throughout the phases of implementation as health care organizations work towards integrating the continuum of care for OAUD into primary care. Implementers can anticipate that staff may perceive substantial barriers at the start of implementation but should note that many barriers can be addressed and that they likely will attenuate over the course of program rollout. However, there may be exceptions, where some barriers remain large or become larger during implementation, particularly those pertaining to medication reimbursement, organizational policies, or workflow constraints. Although the persistence of some barriers could reflect a failure of the parent study to adequately address them, they also could serve to highlight capacity challenges that are particularly difficult to address when implementing OAUD treatment and that may require additional effort and planning. Persistent barriers notwithstanding, the clinic successfully implemented the continuum of care for OAUD and continued to implement the program after the active phases of the study ended. This suggests that while barriers may be sizable and inevitable with some persisting over time, implementation is still possible. These findings contribute to literature on building capacity to implement OAUD treatment in primary care, which ultimately could increase access to treatment for millions of people who need it.

Highlights.

An organizational capacity framework was used to examine barriers to implementing substance use treatment in primary care.

Clinic administrators, medical, and mental health providers participated in interviews and focus groups.

Some barriers persisted, most barriers decreased, and providers reported feeling more efficacious in their ability to deliver treatment.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all providers and staff at the Venice Family Clinic for their contributions to and participation in the study. We thank the SUMMIT team, including the RAND Survey Research Group, Keith Heinzerling, Karen Osilla, David DeVries, Scot Hickey, Brett Ewing, Colleen McCullough, and Tiffany Hruby for their contributions to carrying out the study. We also acknowledge the SUMMIT Scientific Advisory Board for their input on the study design and protocols: Frank de Gruy, Adam J. Gordon, Miriam Komaromy, Tom McLellan, Walter Ling, Harold Pincus, Rick Rawson, Richard Saitz, and Jürgen Unützer.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA034266) awarded to Dr. Katherine E. Watkins. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This paper contains original material, not submitted, in press, under consideration, or published elsewhere in any form. Each author has contributed significantly to the work and agrees to the submission. No conflicts of interest exist. All study protocols and procedures involving human subjects were ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board of the RAND Corporation.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral-Sabadini, Michaela Bitarello do, Saitz R, Souza-Formigoni MLO. Do attitudes about unhealthy alcohol and other drug (AOD) use impact primary care professionals’ readiness to implement AOD-related preventive care? Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29(6):655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DT, Irwin KS, Jones ES, Becker WC, Tetrault JM, Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into office-based practice: a qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(2):218–225. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0881-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Iza M, Rodríguez-Fernández JM, Baca-García E, Wang S, Olfson M. Probability and predictors of treatment-seeking for substance use disorders in the US. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;149:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Iza M, Schwartz RP, Rafful C, Wang S, Olfson M. Probability and predictors of treatment-seeking for prescription opioid use disorders: A national study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;131(1):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blose JO, Holder HD. The utilization of medical care by treated alcoholics: longitudinal patterns by age, gender, and type of care. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1991;3(1):13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S, Louw J, Myers B. Perceptions of organizational functioning in substance abuse treatment facilities in South Africa. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2011;9(3):308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, LaFond A, Macintyre KE. Measuring capacity building. Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Buetow S. Thematic analysis and its reconceptualization as ‘saliency analysis’. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2010;15(2):123–125. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou SP, Grant BF, Dawson DA. Medical consequences of alcohol consumption—United States, 1992. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20(8):1423–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. Dedoose version 7.0.23, web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2016. www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- DeFlavio JR, Rolin SA, Nordstrom BR, Kazal LA., Jr Analysis of barriers to adoption of buprenorphine maintenance therapy by family physicians. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15:3019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Tai B. Challenges and opportunities for integrating preventive substance-use-care services in primary care through the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2014;25(10):36. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Wu L-T, Tai B. Integrating substance abuse care with community diabetes care: Implications for research and clinical practice. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 2013;4:3. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S39982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AC, Holder HD, Nishiura E. Alcoholism treatment offset effects: A cost model. Inquiry. 1991:168–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman AC, Holder HD, Nishiura E, Hankin JR. An analysis of short-term alcoholism treatment cost functions. Medical Care. 1992:795–810. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Karno MP, Warda US, Moore AA, Niv N. Perceptions of need and help received for substance dependence in a national probability survey. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(8):1068–1074. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.8.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MH, Andrukow A, Barr C, Brock K, de Wit M, Embuldeniya D, Malinsky E. The capacity to serve: A qualitative study of the challenges facing Canada’s nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Toronto: Canadian Centre for Philanthropy; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Blose JO. Alcoholism treatment and total health care utilization and costs: A four-year longitudinal analysis of federal employees. JAMA. 1986;256(11):1456–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Blose JO. Typical patterns and cost of alcoholism treatment across a variety of populations and providers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15(2):190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Blose JO. The reduction of health care costs associated with alcoholism treatment: A 14-year longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(4):293–302. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Hallan JB. Impact of alcoholism treatment on total health care costs: A six-year study. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse. 1986;6(1):1–15. doi: 10.1300/J251v06n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schultz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, Guzman R. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles; pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: Application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implementation science : IS. 2007;2:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner N, Ginsburg J, Sulmasy LS. Prescription drug abuse: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(3):198–200. doi: 10.7326/M13-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFond AK, Brown L, Macintyre K. Mapping capacity in the health sector: A conceptual framework. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2002;17(1):3–22. doi: 10.1002/hpm.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(4):197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox RD, Scott-Lennox JA, Holder HD. Substance abuse and family illness: Evidence from health care utilization and cost-offset research. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 1992;19(1):83–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02521310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linzer M, Visser MR, Oort FJ, Smets EM, McMurray JE, de Haes HC. Predicting and preventing physician burnout: Results from the United States and the Netherlands. American Journal of Medicine. 2001;111(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Lu YW, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Weisner CM. Medical and psychiatric conditions of alcohol and drug treatment patients in an HMO: Comparison with matched controls. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163(20):2511–2517. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A-M, Davis M, Mays GP. Defining organizational capacity for public health services and systems research. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2012;18(6):535–544. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31825ce928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York, NY: Guilford press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi Y. Capacity enhancement indicators: Review of the literature. Vol. 2017. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ober AJ, Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Lamp K, Lind M, Setodji CM. An organizational readiness intervention and randomized controlled trial to test strategies for implementing substance use disorder treatment into primary care: SUMMIT study protocol. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0256-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S, Mertens J, Moore C, Weisner C. Utilization and cost impact of integrating substance abuse treatment and primary care. Medical Care. 2003;41(3):357–367. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053018.20700.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S, Weisner C, Hu T-W, Moore C. Association of outpatient alcohol and drug treatment with health care utilization and cost: Revisiting the offset hypothesis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(1):89–97. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter WJ, Levine-Donnerstein D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1999;27(3):258–284. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011;38(2):65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quest TL, Merrill JO, Roll J, Saxon AJ, Rosenblatt RA. Buprenorphine therapy for opioid addiction in rural Washington: The experience of the early adopters. Journal of Opioid Management. 2012;8(1):29–38. doi: 10.5055/jom.2012.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff S, Griffiths B, Forsythe AB, Sherman RM. Utilization of medical services by alcoholics participating in a health maintenance organization outpatient treatment program: Three- year follow- up. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1981;5(4):559–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1981.tb05361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller W. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behaviour. New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks S, Gotham HJ, Johnson K, Padwa H, Murphy DM, Krom L. Integrating substance use disorder and health care services in an era of health reform: models, interventions, and implementation strategies. American Journal of Medical Research. 2016;3(1):75–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA. Potential impact of burnout on the U.S. physician workforce. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2016;91(11):1667–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Kaufman MA, Bosworth HB, Weiner BJ, Zullig LL, Lee SY, Jackson GL. Organizational factors associated with readiness to implement and translate a primary care based telemedicine behavioral program to improve blood pressure control: the HTN-IMPROVE study. Implement Sci. 2013;8:106. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkink J, Fleming M. Adverse health effects and medical complications of alcohol, nicotine, and drug use. Addictive disorders. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book. 1992:145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving innovations into treatment: A stage-based approach to program change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;33(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Firth J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurse researcher. 2011;18(2):52–62. doi: 10.7748/nr2011.01.18.2.52.c8284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD. Medical consequences of substance abuse. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22(2):351–370. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Emergency Department Data. 2011 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/emergency-department-data-dawn Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National survey on drug use and health (NSDUH). Table 2.41B--Alcohol use in lifetime, past year, and past month among persons aged 12 or older, by demographic characteristics: Percentages, 2014 and 2015. 2015a Retrieved June 5, 2017, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm#tab2-41b.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National survey on drug use and health (NSDUH). Table 5.6A--Substance use disorder in past year among persons aged 18 or older, by demographic characteristics: Percentages, 2014 and 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2017. 2015b from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm#tab5-6a.

- Teruya C, Urada D. Integration of substance use disorder treatment with primary care in preparation for health care reform. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;140:e223. [Google Scholar]

- Urada D, Teruya C, Gelberg L, Rawson R. Integration of substance use disorder services with primary care: Health center surveys and qualitative interviews. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2014;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14–4863. Rockville MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Alperen JK, Cheng DM, Botticelli M, Castro-Donlan C, Samet JH, Alford DP. Office-based management of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: Clinical practices and barriers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(9):1393–1398. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0686-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, Lind M, Diamant A, Osilla KC, Pincus HA. Implementing the chronic care model for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2017.0047. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, Lind M, Setodji CM, Osilla KC, Pincus HA. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: The SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;8(4) doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Linnan LA. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Education Research. 2009;24(2):292–305. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]