Abstract

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is caused by a full mutation on the FMR1 gene and a subsequent lack of FMRP, the protein product of FMR1. FMRP plays a key role in regulating the translation of many proteins involved in maintaining neuronal synaptic connections; its deficiency may result in a range of intellectual disabilities, social deficits, psychiatric problems, and dysmorphic physical features. A range of clinical involvement is also associated with the FMR1 premutation, including fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome, fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency, psychiatric problems, hypertension, migraines, and autoimmune problems. Over the past few years, there have been a number of advances in our knowledge of FXS and fragile X-associated disorders, and each of these advances offers significant clinical implications. Among these developments are a better understanding of the clinical impact of the phenomenon known as mosaicism, the revelation that various types of mutations can cause FXS, and improvements in treatment for FXS.

Keywords: whole exome sequencing, point mutations, copy number variants, FMR1 gene

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability (ID) and the most common single-gene cause of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). FXS arises from a full mutation repeat expansion (>200 CGG repeats in the 5′ untranslated region) in the FMR1 gene on the X chromosome; this results in the methylation and subsequent silencing of the gene. Although FXS is the most well-known disorder caused by an FMR1 mutation, there is also a spectrum of disorders associated with the FMR1 premutation (55–200 CGG repeats) 1. Those with the full mutation have symptoms related to the absence or deficiency of FMRP, the protein encoded by the FMR1 gene. These individuals are susceptible to global developmental delay, learning disabilities, and social and behavioral deficits. In contrast, those with the premutation allele have symptoms related to the elevated production of FMR1 mRNA, leading to mRNA toxicity 2. Individuals with the premutation, especially males, are at risk for developing fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), whereas females with the premutation have an increased likelihood of developing fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI) before age 40 3. Although global estimates for the frequency of both the full mutation and premutation exist, recent research has indicated that founder effects, as well as racial and ethnic differences, can significantly affect the risk of individuals in certain regions of the world. Thus, prevalence estimates may be more useful on a smaller, more regional scale 4– 6.

A robust clinical picture of full mutation FXS, as well as the variety of manifestations associated with the premutation, has existed for years; however, the improved understanding of mosaicism has begun to blur this picture. Mosaicism can refer to a condition in individuals who express both full mutation cells and premutation cells (size mosaicism) or individuals who have the full mutation but in whom only a portion of the full mutation alleles are methylated (methylation mosaicism). This may lead to unique cases, such as individuals with features of both FXS and FXTAS 7. Another discovery that has challenged previous understandings of FXS is that mutations other than full mutation repeat expansions have the ability to cause the disorder. The advent of more frequent whole exome sequencing (WES), whole genome sequencing (WGS) and microarray testing has led to the identification of different mutations such as point mutations, deletions, and duplications as causes of FXS. Moreover, these other mutations not only can cause FXS but also can result in partial FMRP functionality and lead to many subtly different phenotypes 8. There have also been rapid advances in the development of targeted treatments for patients with FXS over the past few years, as many animal studies as well as clinical trials have provided researchers with encouraging results. Certain treatments have been shown to reverse aspects of the neurobiological dysfunction in FXS; if used early in development, these treatments are likely to significantly improve the outcome of patients 9, 10.

Clinical presentation of fragile X syndrome

Individuals with FXS present with varying degrees of cognitive impairment depending on sex and the level of FMRP produced 11. Patients producing higher levels of FMRP are typically less cognitively affected. Females with FXS, therefore, may present with a very wide range of clinical involvement due to differences in the activation ratio (AR). The AR refers to the proportion of normal FMR1 alleles on the active X chromosome, which significantly impacts the amount of FMRP a female will produce 12. FMRP production also depends on CGG repeat number as well as the proportion of methylated full mutation alleles; therefore, individuals presenting with mosaicism are also likely to produce more FMRP. In turn, these individuals are typically less cognitively affected than non-mosaic patients with FXS 13.

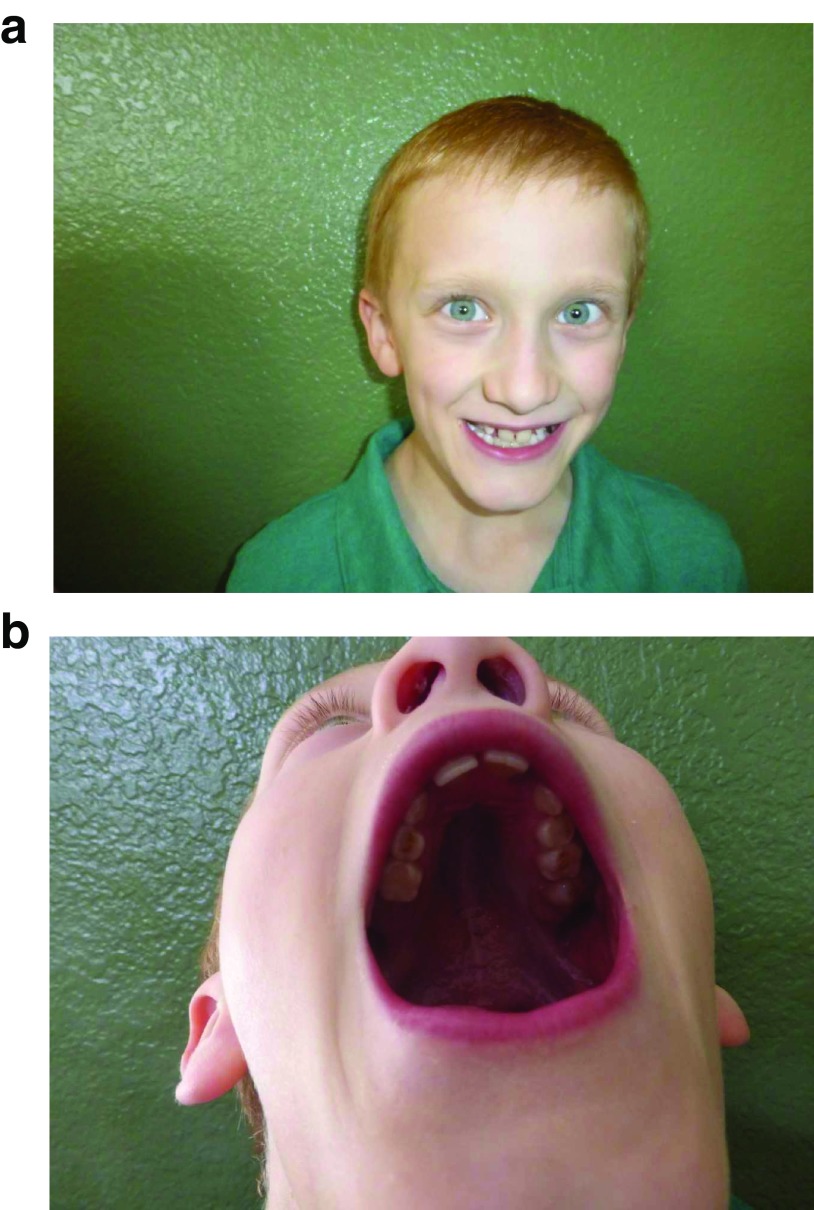

When FMRP levels are not significantly diminished, affected individuals may experience only modest socioemotional and learning deficits with relatively normal IQ levels. However, if FMRP production is severely decreased or fully silenced, moderate to severe cognitive dysfunction is likely to occur 14. In addition to ID, there are several physical features associated with FXS, such as a long face, broad forehead, high-arched palate, prominent ears, macrocephaly, and macroorchidism ( Figure 1 and Table 1) 11. Although not all individuals with FXS will have obviously dysmorphic features, roughly 80% of patients with FXS will present with at least one of these common characteristics 14.

Figure 1.

This 7-year-old boy with fragile X syndrome demonstrates a broad forehead ( a) and a high arched palate ( b) . However, he does not have a long face or prominent ears. He is a high-functioning individual with mosaicism, and DNA testing displays a band at 300 CGG repeats that is methylated as well as bands between 100 and 790 repeats that are unmethylated; overall, 30% of his alleles are unmethylated. He presents with a sequential IQ of 71 and a simultaneous IQ of 83. He has done well with treatment; sertraline has improved his anxiety symptoms, and a long-acting methylphenidate preparation has improved his attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms.

Table 1. Clinical features of fragile X syndrome.

| Clinical characteristics | Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Long face

Macrocephaly Prominent ears Prominent jaw Flat feet Joint hypermobility Macroorchidism |

83%; occurs more commonly in adults

50–81% 75% 80%; occurs in adults only 29–69% 50–70%; occurs less commonly in adults 95%; occurs in adolescents and adults |

| Psychological | Attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder Anxiety Autism spectrum disorder |

80% of boys and 40% of girls

58–86% 30–60% |

| Developmental | Intellectual disability

Language deficits |

85% of boys and 25–30% of girls

~100% of boys and 60–75% of girls |

| Other | Strabismus

Recurrent otitis Gastrointestinal complaints Obesity Seizures |

8–30%

47–75%; occurs in the first 5 years of life 31% 30–61% 15–20% |

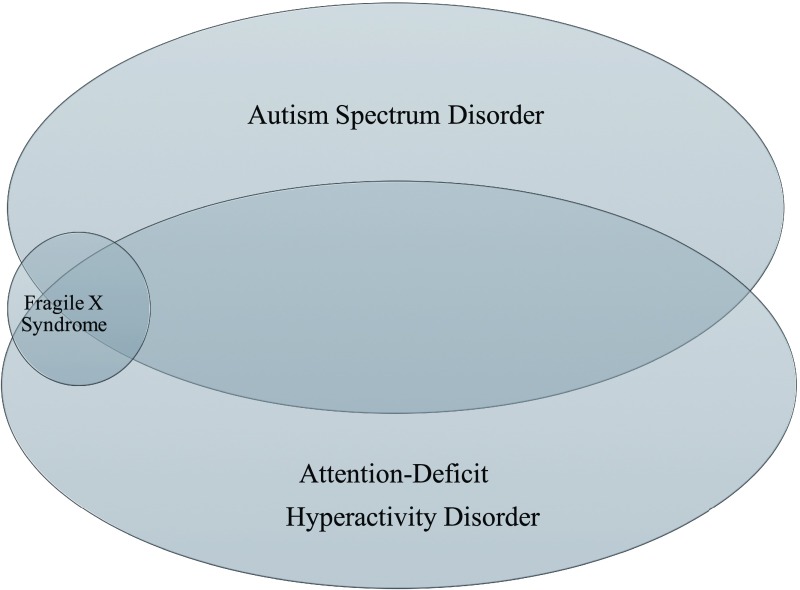

A significant overlap exists between FXS and ASD. Monogenic disorders account for nearly one fifth of all diagnosed cases of ASD, and the most common of these monogenic causes is FXS 16. Many of the behavioral characteristics seen in individuals with FXS, such as impaired social communication, social anxiety, social gaze avoidance, and stereotypic behaviors, are the same traits seen in other causes of ASD. Moreover, a large portion of both individuals with FXS and individuals with ASD meet criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder ( Figure 2). Just as ASD is seen more often in males than females, males with FXS meet ASD criteria more frequently (60%) than do females (20%) 17. The overlap between FXS and ASD also has a molecular basis, as FMRP controls the translation of approximately 30% of the genes associated with ASD 18. These observations demonstrate that the underlying molecular etiologies of these disorders are intertwined, and targeted treatments of FXS may be helpful for other types of ASD.

Figure 2. There is significant overlap between fragile X syndrome (FXS), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Approximately 60% of all patients with FXS also meet criteria for ASD, although FXS accounts for only 2% to 6% of all cases of ASD. Furthermore, nearly 80% of children with FXS and 50% of children with ASD have co-occurring ADHD 21, 22.

Clinical presentation of premutation disorders

Premutation expansions are associated with a variety of clinical manifestations, including psychiatric, developmental, and neurological problems. The premutation causes psychiatric problems, such as depression and anxiety, in approximately 50% of carriers. It also causes premature ovarian failure (menopause occurring before the age of 40) in a significant number of female carriers. This condition, known as FXPOI, occurs in 16% to 20% of female carriers; moreover, an additional 20% of carriers will experience menopause before the age of 45. Some clinical manifestations seen in those with the premutation are relatively common, even in individuals with normal FMR1 alleles; however, their prevalence in premutation carriers is typically higher than their prevalence in the general population ( Table 2). The greatest clinical involvement associated with the premutation expansion results from the neurodegenerative phenotype known as FXTAS, which occurs in 40% of aging males and 16% of aging females with the premutation 19. FXTAS is a late-onset condition characterized by intention tremor, cerebellar ataxia leading to frequent falling, neuropathy, parkinsonian features, autonomic dysfunction, and cognitive decline 20. It is the most severe phenotype of premutation-associated disorders. FXTAS is also characterized by generalized brain atrophy and white matter disease in the middle cerebellar peduncle and the splenium of the corpus callosum. In addition, FXTAS is accompanied by the presence of intranuclear inclusions in both neurons and astrocytes in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as neurons in the peripheral nervous system 19, 20.

Table 2. Clinical involvement associated with the premutation.

| Phenotype | Prevalence (premutation carriers versus general population) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male carriers | Female

carriers |

Male

non-carriers |

Female

non-carriers |

|

| FXTAS | 40% | 16% | N/A | N/A |

| Fragile X-associated

primary ovarian insufficiency |

N/A | 16–20% | N/A | ~1% (primary

ovarian insufficiency) |

| Hypertension | 57% | 22% | ~30% | ~30% |

| Migraine | 27% | 54% | ~12% | ~20% |

| Neuropathy | 62% | 17% | <5% | <5% |

| Sleep apnea | 32% with FXTAS | 32% with FXTAS | ~15% | ~5% |

| Psychiatric problems | ~50% | ~50% | ~ 3.6%

(>45 years old) |

~10.3%

(>45 years old) |

Premutation disorders in extended family members are often identified when a proband is diagnosed with FXS, after which the proband’s mother is typically found to have the premutation. Moreover, if the grandfather of the proband also has the premutation, this means that all of the mother’s sisters will be obligate carriers as well. The FMR1 premutation is known to be the most common genetic cause of primary ovarian insufficiency 2; thus, premutation disorders are now also being identified through OB-GYN offices, when fragile X DNA testing is ordered after seeing ovarian dysfunction. If a female is diagnosed with the premutation, her offspring have a 50% chance of inheriting a fragile X mutation; whether offspring inherit a premutation or a full mutation depends on the number of CGG repeats in the mother as well as on the number of AGG “anchors” present 29. AGG triplets, which typically interrupt CGG triplets after every nine or ten repeats, have been shown to decrease the likelihood of expansion to the full mutation when passed on to the next generation. Therefore, higher numbers of these AGG anchors in the maternal FMR1 gene lower the risk of the full mutation in the offspring 29. If a male has the premutation, all of his daughters will also carry the premutation and are at risk of having children affected with FXS 20.

Mosaicism

Two types of mosaicism exist: size mosaicism and methylation mosaicism. Size mosaicism refers to a condition in individuals carrying both cells with the premutation and cells with the full mutation in their blood. Furthermore, the ratio of premutation cells versus full mutation cells in the blood may differ when compared with other tissues, such as fibroblasts and brain tissue 13, 30. Methylation mosaicism refers to a condition in individuals who have the full mutation but only a portion of the cells containing full mutation alleles are methylated; methylation status may vary from tissue to tissue as well 30. The presence of either type (or both types) of mosaicism can blur the boundaries between the phenotypes of the premutation and the full mutation (FXS).

Individuals with methylation mosaicism produce more FMRP than individuals with fully methylated full mutation alleles 31. Additionally, CGG repeat numbers in the premutation range and FMRP expression are inversely related 32; therefore, individuals with size mosaicism who carry premutation alleles in addition to full mutation alleles will likely also produce more FMRP than non-mosaic individuals. Increased FMRP levels in FXS are associated with fewer clinical symptoms and correlate directly with IQ 30; thus, individuals with mosaicism tend to be higher-functioning. For example, one postmortem case study looked at multiple tissues of a high-functioning patient displaying both size mosaicism and methylation mosaicism. Only one region of the brain, the parietal lobe, had a methylated full mutation and silenced FMRP expression. However, FMRP was expressed in other parts of the brain, including the superior temporal cortex, frontal cortex, and hippocampus, which likely explains why this patient had only mild cognitive and behavioral deficits 33. Although mosaic individuals with FXS may be less cognitively impaired than non-mosaic individuals with FXS, they are more likely to develop FXTAS if their mRNA levels are elevated 1, 20. This can lead to an intriguing scenario known as the “double hit” phenomenon, in which an individual is affected by both lowered FMRP levels and elevated FMR1 mRNA levels 34.

In 2013, Schneider and colleagues 34 documented two brothers in their 40s who both displayed this double hit of elevated FMR1 mRNA levels and moderately decreased FMRP expression. The first brother, an individual with methylation mosaicism, presented with multiple physical features characteristic of FXS, such as macroorchidism, flat feet, and a prominent jaw. He was cognitively high-functioning but also displayed psychotic symptoms, including a history of bipolar 1 disorder. The second brother carried the premutation (118 CGG repeats); he experienced typical development but presented with a few physical features of FXS. Additionally, he presented with psychotic features associated with major depressive disorder. Another case report documented a 58-year-old male with size and methylation mosaicism and CGG repeats ranging from 20 to 800 30. He presented with a slightly below average IQ and physical features of FXS. At age 50, he experienced neurodegenerative symptoms characteristic of FXTAS, including a worsening tremor and severe ataxia; he eventually experienced the cognitive decline typical of males with FXTAS. However, he was also an alcoholic, which may have increased CNS toxicity and exacerbated his FXTAS progression. Interestingly, he also met criteria for bipolar I disorder; taken together, these reports indicate that individuals with a double hit may be at an increased psychopathological risk. Additionally, these case studies challenge the traditionally clear distinction between FXS and premutation disorders and support the notion of a spectrum-based nature of disorders associated with FMR1 mutations.

Epidemiology

The reported rates of prevalence of FXS in the general population have been estimated to be approximately 1:5,000 males and 1:4,000 to 1:8,000 females 35– 37. However, the estimated prevalence of the mutation has varied because of the differing testing methodologies that have been used over time. Since FMR1 testing began, the primary means of diagnosis has moved from cytogenetic testing for the presence of a folate-sensitive fragile site, to Southern blot analyses, to polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques. Additionally, wide variations in prevalence that are seen in different populations make global prevalence estimates difficult 38, 39.

To attempt to address these issues, Hunter and colleagues carried out a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of expanded FMR1 alleles by using a random effects statistical model to analyze 54 epidemiological studies 39. After accounting for characteristics of the populations (that is, subjects with or without ID) and including only studies that used PCR and Southern blot techniques, obtaining screening data on over 90,000 females and 50,000 males; the determined rates of prevalence of the full mutation were 1:7,143 males and 1:11,111 females 39. Additionally, meta-analyses investigating the prevalence of premutation alleles among the general population have determined estimated frequencies of 1:150–300 females and 1:400–850 males 35, 39, 40. Although we are gaining a better understanding of the prevalence of repeat expansions, this is not the only type of mutation that can cause the disorder; a growing number of deletions and point mutations on FMR1 have been identified in patients with FXS 41, 42. However, because repeat expansions are tested far more frequently than these other mutations, it is likely that the number of patients with FXS with non-repeat mutations has been underestimated. Ideally, this epidemiological shortcoming will be ameliorated through the increased use of WES and microarray testing going forward.

The frequency of expanded FMR1 alleles varies globally because of both founder effects and racial differences in haplotypes that may predispose individuals in certain regions of the world to CGG expansions 43. Recently, the highest prevalence of expanded alleles has been reported in Ricuarte, a small town in Colombia 4. In Ricuarte, the rates of prevalence of the full mutation are 1:21 males and 1:49 females, whereas the frequencies of the premutation are 1:71 males and 1:28 females. This genetic cluster is likely a consequence of a strong founder effect from founding families that migrated from Spain. In sharp contrast to Ricuarte is Ireland, which has extremely low rates of prevalence of the full mutation: 1:10,619 males and 1:43,540 females. Researchers in Ireland speculate that a lineage-specific haplotype is responsible for this low incidence 43. China also has a relatively low reported incidence of FXS; however, owing to a gap between China and Western countries regarding FXS awareness, it is likely that a significant number of potential patients with FXS in China have been misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed 6. Other genetic clusters of fragile X mutations can be found in various parts of the world, including Indonesia, Finland, and the Spanish island of Mallorca 5, 44, 45. These observations suggest that the prevalence of FXS should be estimated separately in different countries or continental regions, as certain shared predispositions or strong instances of founder effects can lead to significantly different prevalence rates.

Non-traditional ways of developing fragile X syndrome

FXS is almost always diagnosed through molecular testing for a CGG repeat expansion in the triplet repeat sequence of FMR1, as this is by far the most frequent cause of FXS 8. However, recent studies have implicated other mutations, such as point mutations and deletions, in those with FXS 41, 42, 46. There is nothing inherent about repeat expansions in the full mutation that cause the disorder; rather, it is the reduced FMRP production that leads to FXS 8. Thus, it is likely that any FMR1 mutation that adversely affects the production of functional FMRP will lead to FXS. Indeed, a review of non-expansion FMR1 mutations documented various deletions causing FXS; over 20 case reports documented FXS in patients who had normal CGG repeat numbers but had deletions of varying sizes in the triplet repeat sequence or flanking regions 42.

Though less common, numerous point mutations in FMR1 have also been discovered in individuals with FXS and other developmental delays. In 2014, researchers documented FXS in a patient with a loss-of-function missense mutation (p.(Gly266Glu)) and a CGG repeat number of only 23 8. A separate case study attributed a patient’s FXS to a loss-of-function nonsense mutation (p.(Ser27X); this patient’s CGG repeat number was just 29 46. These case studies corroborate the notion that any mutation that interferes with the function of FMRP, not just full repeat expansions, can lead to FXS. Furthermore, two related studies sequenced the FMR1 gene of hundreds of developmentally delayed males who did not meet diagnostic criteria for FXS; these mass sequencings revealed a total of three novel FMR1 missense mutations 41, 47. Usually, developmentally delayed individuals with point mutations on FMR1 have some of the features of FXS, although their phenotype may vary in some ways from that of the typical patient with FXS 8, 48.

Targeted treatments

Significant advances have been made in the development of treatments for FXS. Animal models, including the FMR1 knockout (KO) mouse and the Drosophila fly model, have provided researchers with several promising leads regarding effective pharmacological interventions for patients with FXS. In addition, many clinical trials have been carried out in the past few years and have been summarized in multiple comprehensive reviews 49, 50. Moreover, a number of these trials have led to medications that are now available for use by treating physicians. Minocycline, for example, is a semisynthetic tetracycline derivative that was first proven to be effective in improving anxiety and cognition in KO mice 51. A 3-month, double-blind controlled trial of minocycline in children and adolescents with FXS resulted in an improvement in global functioning as well as significant improvements in anxiety and mood-related behaviors 52. Lovastatin, a specific inhibitor of the cholesterol biosynthesis enzyme 3HMG-CoA reductase, has also shown promising results in KO mice; in these mice, lovastatin decreased excessive protein production and blocked epileptiform activity in the mice hippocampi 9. A controlled trial combining lovastatin treatment with parent-implemented language intervention (PILI) is currently being carried out at the UC Davis MIND Institute, investigating whether this combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions will improve spoken language and behavior in children with FXS.

Another targeted treatment for FXS informed by animal studies is metformin, a drug that is currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for both obesity and type 2 diabetes. Drosophila fly models of FXS, as well as KO mice, have displayed metformin’s ability to improve defects in circadian rhythm, memory deficits, and social novelty 53– 55. Clinically, a recent open-label study saw anecdotal reports of improved behavior and language in children and adults with FXS 56, 57. Although initially metformin was hypothesized to be helpful in only those with the Prader-Willi phenotype (PWP) of FXS, associated with hyperphagia and severe obesity 56, this study suggests that patients without PWP or obesity may also benefit. This study demonstrates the need for a large controlled trial of metformin to see whether improvements in behavior, cognition, and language can be seen in children and adults with FXS.

The neurobiological overlap between ASD and FXS has led to the trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), specifically sertraline, to help alleviate the low serotonin levels seen in the CNS of those with ASD 10, 58. Metabolomic studies in various cases of ASD have demonstrated depressed levels of enzymes with the ability to metabolize tryptophan into serotonin, indicating that an SSRI may be helpful 59. An initial retrospective study of young children with FXS demonstrated a significantly improved receptive and expressive language trajectory in those on sertraline compared with those not on sertraline 60. A subsequent double-blind controlled trial of low-dose sertraline in young children with FXS found significant improvements in fine motor skills, visual reception, and the composite T score on the Mullen Scales of Early Development (MSEL). In a post-hoc assessment, the children with FXS together with ASD (60% of the study population) demonstrated significant improvement in expressive language on the MSEL when on sertraline 61.

Mavoglurant, an mGluR5 antagonist, has also been helpful in animal models, but efficacy has not been demonstrated in adolescents and adults with FXS 62. Similarly, arbaclofen, a GABAB agonist, has not shown efficacy in adults; however, outcome data for a limited number of measures in children look more promising 63. There may be a number of reasons for the failure of some trials to demonstrate efficacy. The outcome measures in many previous studies included only behavioral checklists, which are subject to parental bias 62, 63. Additionally, studies of arbaclofen and sertraline suggest that young children may respond better to targeted treatments than adults with FXS 21, 61. Addressing some of these concerns, a current trial of mavoglurant combined with PILI in young children with FXS is using novel outcome measures such as event-related potentials (ERPs), eye tracking methodology, and language sampling to better detect cognitive benefits and improvement in CNS function. Overall, a multitude of targeted treatments for FXS have provided researchers with encouraging results; however, much more research is needed before we can establish which interventions, or combinations of interventions, are the most effective for this population.

Whereas a significant amount of research has been dedicated toward treatments for FXS, research into targeted treatments for FXTAS and other premutation disorders is just beginning. A controlled trial of memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist commonly used to treat Alzheimer’s disease, did not demonstrate improvements in tremor, ataxia, or executive function deficits in individuals with FXTAS 64. However, ERP studies demonstrated improvements in brain processing and attention in individuals with FXTAS when treatment was memantine versus placebo 65, 66. A more recent open-label study demonstrated that a weekly dose of intravenous allopregnanolone, a GABAA agonist, over the course of 12 weeks in patients with FXTAS resulted in improvements in both neuropsychological testing and neuropathy symptoms 67. As mentioned earlier, researchers are still in the early stages of finding effective targeted treatments for FXTAS and other premutation disorders, and there are many more clinical trials expected to come.

Conclusions

Our understanding of FXS and other fragile X-associated disorders has grown significantly in recent years. It has become clear that disorders related to FMR1 mutations are associated with a wide range of clinical presentations; there is a continuum of clinical involvement from premutation disorders into full mutation disorders due to both low FMRP and high FMR1 mRNA. Some studies, such as reports indicating that high-functioning individuals with mosaicism are at risk for FXTAS, illustrate the ability of mosaicism to cloud the clinical picture of FXS and premutation-related phenotypes. Additionally, the number of detected deletions and point mutations in FMR1 will continue to increase with the more widespread use of WES, WGS and the identification of these non-repeat mutations is further widening the spectrum of clinical involvement in FXS. Lastly, there is a promising outlook for effective targeted treatments; several medications have shown encouraging results in both animal models and clinical settings, and there are likely many more effective interventions to be found.

Ethics

Written informed consent for the publication of the image found in Figure 1 was obtained from the child's parent.

Editorial Note on the Review Process

F1000 Faculty Reviews are commissioned from members of the prestigious F1000 Faculty and are edited as a service to readers. In order to make these reviews as comprehensive and accessible as possible, the referees provide input before publication and only the final, revised version is published. The referees who approved the final version are listed with their names and affiliations but without their reports on earlier versions (any comments will already have been addressed in the published version).

The referees who approved this article are:

Karen Usdin, Section on Gene Structure and Disease, Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

R Frank Kooy, Department of Medical Genetics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

Funding Statement

This work was supported through the following grants: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant (NICHD) HD036071; the MIND Institute Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (NICHD U54 HD079125), HRSA R40MC26641, and HHS-ADD 90DD05969 for the Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities support and the International Training Program for Neurodevelopmental Disorders at the MIND UC Davis Medical Center.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Lozano R, Rosero CA, Hagerman RJ: Fragile X spectrum disorders. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3(4):134–46. 10.5582/irdr.2014.01022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hagerman R, Hagerman P: Advances in clinical and molecular understanding of the FMR1 premutation and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):786–98. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70125-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sullivan AK, Marcus M, Epstein MP, et al. : Association of FMR1 repeat size with ovarian dysfunction. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(2):402–12. 10.1093/humrep/deh635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saldarriaga W, et al. : Genetic Cluster of Fragile X Syndrome In A Colombian District. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2017, (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oudet C, von Koskull H, Nordström AM, et al. : Striking founder effect for the fragile X syndrome in Finland. Eur J Hum Genet. 1993;1(3):181–9. 10.1159/000472412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jin X, Chen L: Fragile X syndrome as a rare disease in China - Therapeutic challenges and opportunities. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2015;4(1):39–48. 10.5582/irdr.2014.01037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 7. Basuta K, Schneider A, Gane L, et al. : High functioning male with fragile X syndrome and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(9):2154–61. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myrick LK, Nakamoto-Kinoshita M, Lindor NM, et al. : Fragile X syndrome due to a missense mutation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(10):1185–9. 10.1038/ejhg.2013.311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Osterweil EK, Chuang S, Chubykin AA, et al. : Lovastatin corrects excess protein synthesis and prevents epileptogenesis in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2013;77(2):243–50. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanson AC, Hagerman RJ: Serotonin dysregulation in Fragile X Syndrome: implications for treatment. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2014;3(4):110–7. 10.5582/irdr.2014.01027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ciaccio C, Fontana L, Milani D, et al. : Fragile X syndrome: a review of clinical and molecular diagnoses. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43(1):39. 10.1186/s13052-017-0355-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 12. Sobesky WE, Taylor AK, Pennington BF, et al. : Molecular/clinical correlations in females with fragile X. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64(2):340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pretto DI, Mendoza-Morales G, Lo J, et al. : CGG allele size somatic mosaicism and methylation in FMR1 premutation alleles. J Med Genet. 2014;51(5):309–18. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saldarriaga W, Tassone F, González-Teshima LY, et al. : Fragile X syndrome. Colomb Med. 2014;45(4):190–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ: Fragile X Syndrome. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.2002. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Dafoulis V, et al. : Autism spectrum disorders: the quest for genetic syndromes. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B(4):327–66. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee M, Martin GE, Berry-Kravis E, et al. : A developmental, longitudinal investigation of autism phenotypic profiles in fragile X syndrome. J Neurodev Disord. 2016;8:47. 10.1186/s11689-016-9179-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 18. Iossifov I, O'Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, et al. : The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515(7526):216–21. 10.1038/nature13908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polussa J, Schneider A, Hagerman R: Molecular Advances Leading to Treatment Implications for Fragile X Premutation Carriers. Brain Disord Ther. 2014;3: pii: 1000119. 10.4172/2168-975X.1000119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hagerman RJ, Hagerman P: Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome - features, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(7):403–12. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raspa M, Wheeler AC, Riley C: Public Health Literature Review of Fragile X Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;139(Suppl 3):S153–S171. 10.1542/peds.2016-1159C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 22. Kaufmann WE, Kidd SA, Andrews HF, et al. : Autism Spectrum Disorder in Fragile X Syndrome: Cooccurring Conditions and Current Treatment. Pediatrics. 2017;139(Suppl 3):S194–S206. 10.1542/peds.2016-1159F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 23. Coffey SM, Cook K, Tartaglia N, et al. : Expanded clinical phenotype of women with the FMR1 premutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(8):1009–16. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sherman SL: Premature ovarian failure in the fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97(3):189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McDonald M, Hertz RP, Unger AN, et al. : Prevalence, awareness, and management of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes among United States adults aged 65 and older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):256–63. 10.1093/gerona/gln016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bolay H, Ozge A, Saginc P, et al. : Gender influences headache characteristics with increasing age in migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(9):792–800. 10.1177/0333102414559735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berry-Kravis E, Goetz CG, Leehey MA, et al. : Neuropathic features in fragile X premutation carriers. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(1):19–26. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. : Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: An Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. U.S Preventie Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, Evidence Synthesis No.146(AHRQ Publication 14-05216-EF-1).2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yrigollen CM, Durbin-Johnson B, Gane L, et al. : AGG interruptions within the maternal FMR1 gene reduce the risk of offspring with fragile X syndrome. Genet Med. 2012;14(8):729–36. 10.1038/gim.2012.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pretto D, Yrigollen CM, Tang HT, et al. : Clinical and molecular implications of mosaicism in FMR1 full mutations. Front Genet. 2014;5:318. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Loesch DZ, Huggins RM, Hagerman RJ: Phenotypic variation and FMRP levels in fragile X. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10(1):31–41. 10.1002/mrdd.20006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ludwig AL, Espinal GM, Pretto DI, et al. : CNS expression of murine fragile X protein (FMRP) as a function of CGG-repeat size. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(23):3228–38. 10.1093/hmg/ddu032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor AK, Tassone F, Dyer PN, et al. : Tissue heterogeneity of the FMR1 mutation in a high-functioning male with fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84(3):233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schneider A, Seritan A, Tassone F, et al. : Psychiatric features in high-functioning adult brothers with fragile x spectrum disorders. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(2): pii: PCC.12l01492. 10.4088/PCC.12l01492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tassone F, Iong KP, Tong TH, et al. : FMR1 CGG allele size and prevalence ascertained through newborn screening in the United States. Genome Med. 2012;4(12):100. 10.1186/gm401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coffee B, Keith K, Albizua I, et al. : Incidence of fragile X syndrome by newborn screening for methylated FMR1 DNA. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(4):503–14. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tassone F: Advanced technologies for the molecular diagnosis of fragile X syndrome. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(11):1465–73. 10.1586/14737159.2015.1101348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hagerman PJ: The fragile X prevalence paradox. J Med Genet. 2008;45(8):498–9. 10.1136/jmg.2008.059055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, et al. : Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(7):1648–58. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hall D, Mailick M: The epidemiology of FXTAS. In FXTAS, FXPOI, and Other Premutation Disorders, F. Tassone, Editor. Springer: Switzerland.2016;25–38. 10.1007/978-3-319-33898-9_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Handt M, Epplen A, Hoffjan S, et al. : Point mutation frequency in the FMR1 gene as revealed by fragile X syndrome screening. Mol Cell Probes. 2014;28(5–6):279–83. 10.1016/j.mcp.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wells RD: Mutation spectra in fragile X syndrome induced by deletions of CGG*CCG repeats. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):7407–11. 10.1074/jbc.R800024200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. O'Byrne JJ, Sweeney M, Donnelly DE, et al. : Incidence of Fragile X syndrome in Ireland. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(3):678–83. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 44. Mundhofir FEP, Winarni TI, Nillesen W, et al. : Prevalence of fragile X syndrome in males and females in Indonesia. WJMG. 2012;2(3):15–22. 10.5496/wjmg.v2.i3.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alfaro Arenas R, Rosell Andreo J, Heine Suñer D: Fragile X syndrome screening in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy shows a remarkably high FMR1 premutation prevalence in the Balearic Islands. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171(8):1023–31. 10.1002/ajmg.b.32470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 46. Grønskov K, Brøndum-Nielsen K, Dedic A, et al. : A nonsense mutation in FMR1 causing fragile X syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(4):489–91. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Collins SC, Bray SM, Suhl JA, et al. : Identification of novel FMR1 variants by massively parallel sequencing in developmentally delayed males. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(10):2512–20. 10.1002/ajmg.a.33626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quartier A, Poquet H, Gilbert-Dussardier B, et al. : Intragenic FMR1 disease-causing variants: a significant mutational mechanism leading to Fragile-X syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(4):423–31. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 49. Berry-Kravis E: Mechanism-based treatments in neurodevelopmental disorders: fragile X syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50(4):297–302. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ligsay A, Hagerman RJ: Review of targeted treatments in fragile X syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016;5(3):158–67. 10.5582/irdr.2016.01045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bilousova TV, Dansie L, Ngo M, et al. : Minocycline promotes dendritic spine maturation and improves behavioural performance in the fragile X mouse model. J Med Genet. 2009;46(2):94–102. 10.1136/jmg.2008.061796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leigh MJ, Nguyen DV, Mu Y, et al. : A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of minocycline in children and adolescents with fragile x syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34(3):147–55. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318287cd17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Monyak RE, Emerson D, Schoenfeld BP, et al. : Insulin signaling misregulation underlies circadian and cognitive deficits in a Drosophila fragile X model. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(8):1140–8. 10.1038/mp.2016.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 54. Weisz ED, Monyak RE, Jongens TA: Deciphering discord: How Drosophila research has enhanced our understanding of the importance of FMRP in different spatial and temporal contexts. Exp Neurol. 2015;274(Pt A):14–24. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 55. Gantois I, Khoutorsky A, Popic J, et al. : Metformin ameliorates core deficits in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat Med. 2017;23(6):674–7. 10.1038/nm.4335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 56. Muzar Z, Lozano R, Kolevzon A, et al. : The neurobiology of the Prader-Willi phenotype of fragile X syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016;5(4):255–61. 10.5582/irdr.2016.01082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dy ABC, Tassone F, Eldeeb M, et al. : Metformin as targeted treatment in fragile X syndrome. Clin Genet. 2017. 10.1111/cge.13039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chandana SR, Behen ME, Juhász C, et al. : Significance of abnormalities in developmental trajectory and asymmetry of cortical serotonin synthesis in autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(2–3):171–82. 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boccuto L, Chen CF, Pittman AR, et al. : Decreased tryptophan metabolism in patients with autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):16. 10.1186/2040-2392-4-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Indah Winarni T, Chonchaiya W, Adams E, et al. : Sertraline may improve language developmental trajectory in young children with fragile x syndrome: a retrospective chart review. Autism Res Treat. 2012;2012: 104317. 10.1155/2012/104317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Greiss Hess L, Fitzpatrick SE, Nguyen DV, et al. : A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Low-Dose Sertraline in Young Children With Fragile X Syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37(8):619–28. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Berry-Kravis E, Des Portes V, Hagerman R, et al. : Mavoglurant in fragile X syndrome: Results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(321):321ra5. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab4109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Recommendation

- 63. Berry-Kravis E, Hagerman R, Visootsak J, et al. : Arbaclofen in fragile X syndrome: results of phase 3 trials. J Neurodev Disord. 2017;9:3. 10.1186/s11689-016-9181-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Seritan AL, Nguyen DV, Mu Y, et al. : Memantine for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(3):264–71. 10.4088/JCP.13m08546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yang JC, Niu YQ, Simon C, et al. : Memantine effects on verbal memory in fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS): a double-blind brain potential study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(12):2760–8. 10.1038/npp.2014.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yang JC, Rodriguez A, Royston A, et al. : Memantine Improves Attentional Processes in Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome: Electrophysiological Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21719. 10.1038/srep21719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang JY, Trivedi AM, Carrillo NR, et al. : Open-Label Allopregnanolone Treatment of Men with Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;1–11. 10.1007/s13311-017-0555-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]