Key Points

Intragenic PAX5 amplification defines a novel, relapse-prone subtype of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a poor outcome.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy, characterized by a wide spectrum of genetic abnormalities, which are used in risk stratification for treatment.1 PAX5 encodes a transcription factor, which plays a key role in B-cell commitment and maintenance2 and is frequently (20% to 35%) deleted or mutated in BCP-ALL.3-5 Germline PAX5 mutations also occur in familial ALL.6,7 Furthermore, chromosomal rearrangements involving PAX5 result in the expression of potentially oncogenic PAX5 fusion genes.8-12 Here we present a subset of patients with BCP-ALL lacking the major cytogenetic abnormalities (ETV6-RUNX1, BCR-ABL1, and TCF3-PBX1 fusions, high hyperdiploidy, near-haploidy, low hypodiploidy, MLL rearrangements, or intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21)1 with intragenic amplifications of PAX5 (PAX5AMP).

Methods

Patients in this study originated from 15 international study groups. All participating centers obtained local ethical committee approval and written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Diagnosis of BCP-ALL was confirmed by immunophenotyping, according to standard criteria. Demographic and clinical details are summarized in supplemental Table 1.

The copy numbers of individual PAX5 exons were determined using the SALSA multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) kit P335 IKZF1 (MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), as previously described (supplemental Methods).13-15 Thirteen PAX5AMP samples were processed on SNP6.0 or CytoScan HD arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA; supplemental Methods). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), using PAX5 locus-specific probes, was carried out on 26 cases (supplemental Figures 1 and 2).

Survival analysis considered event-free survival, defined as time to relapse, and overall survival, defined as time to death, both censored at last contact. Very early relapse was defined as within 18 months of diagnosis, early relapse as >18 months and ≤6 months after the end of treatment, with late relapse defined as occurring >6 months posttreatment. Survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using univariate Cox regression models. All analyses were performed using Intercooled Stata 14.0 (Stata, College Station, TX).

Results and discussion

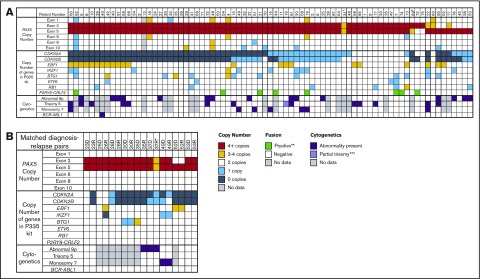

PAX5AMP was identified in 79 patients with BCP-ALL, at diagnosis in 77 cases; only relapse material was available from 2 patients (Figures 1 and 2A). The amplified region encompassed exons 2 and 5 (n = 68), exon 5 only (n = 9), or exon 2 only (n = 2), encoding the DNA-binding and octapeptide domains (Figure 1). The extent of PAX5AMP identified by MLPA was confirmed by single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays (n = 13; Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 3; GEO database accession number GSE99813). Amplification of the exons identified by MLPA was validated by quantitative genomic polymerase chain reaction (n = 18; data not shown), as previously described.15 Because this MLPA approach did not target PAX5 exons 3 and 4, the extent of the amplified region in cases with exon 2 or 5 amplification remains unknown. Several patients with PAX5AMP also presented with deletions (n = 8) and gains (3-4 copies; n = 9) of other PAX5 exons (Figure 2). The same amplification was present in 9 matched diagnosis and relapse samples (Figure 2B). FISH analysis excluded the presence of PAX5 rearrangements and confirmed that the amplification was located within the PAX5 locus (supplemental Figure 2). Whether PAX5AMP results in expression of structurally mutant PAX5 proteins or loss of function remains to be determined.

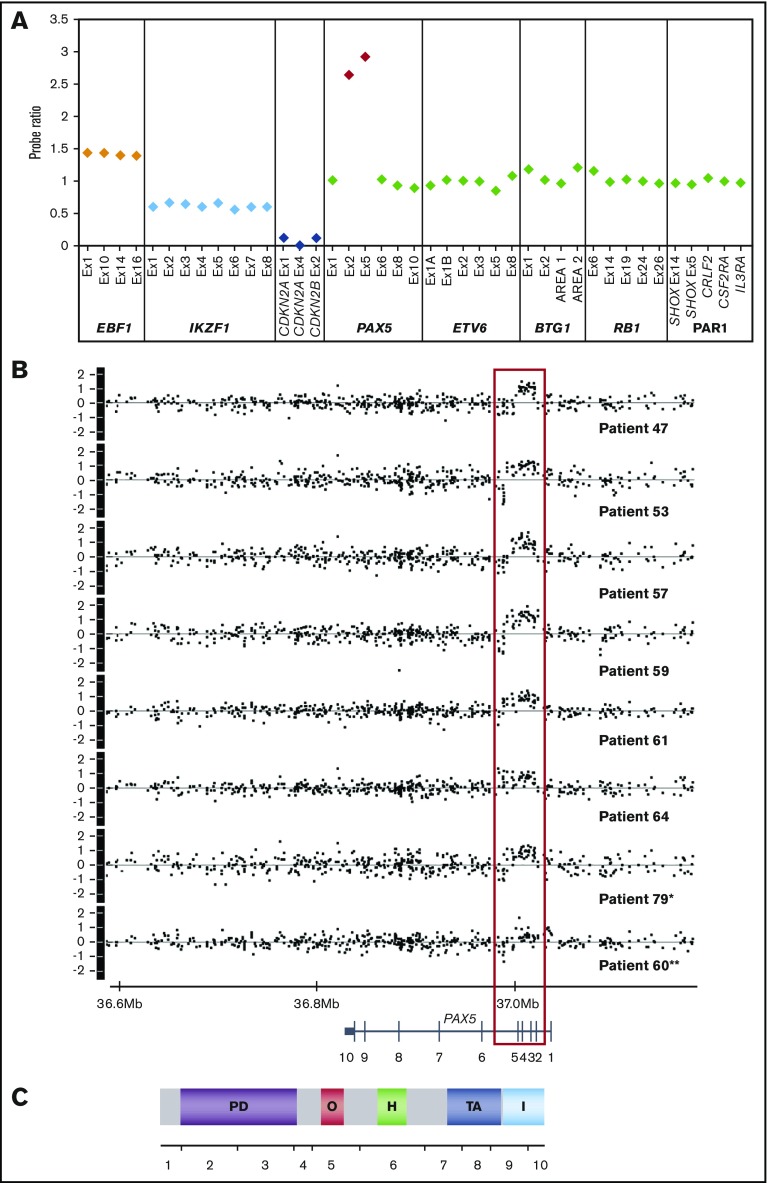

Figure 1.

MLPA and SNP6.0 profiles of patients with PAX5AMP. (A) Example of MLPA results using the P335 IKZF1 MLPA kit. The plot shows the probe ratio for each target contained in the kit (EBF1, 4 probes; IKZF1, 8 probes; CDKN2A/B, 3 probes; PAX5, 6 probes; ETV6, 6 probes; BTG1, 4 probes; RB1, 5 probes; and the PAR1 region, CRLF2, CSF2RA, and IL3RA, 1 probe each). Probe ratio values between 0.75 and 1.3 were considered to be within the normal range, equivalent to the normal copy number of 2. Values <0.75 or >1.3 indicated loss or gain, respectively, and a value <0.25 indicated biallelic loss. These values correspond to copy numbers of 1, 3 and 4, and 0, respectively. A value ≥2.0 corresponds to a copy number of ≥4 and was interpreted as amplification. Approximate copy numbers of amplified exons ranged from 4 to 22 (median, 5.86). Ratio values of 1 representative patient (patient 64) showing amplification of PAX5 encompassing exons 2 and 5, gain of EBF1 consistent with trisomy 5 in this patient, monoallelic loss of IKZF1, and biallelic loss of CDKN2A/B. (B) Copy number profiles (log2ratio) of the PAX5 locus of 8 patients with PAX5AMP processed on the SNP6.0 array. *In patient 79, PAX5 amplification was identified at relapse with no material available from diagnosis. **Patient 60 shows amplification of exon 5 only and gain of exons 1 to 4. (C) Exon and protein structure of PAX5; the amplified region encodes the DNA-binding paired domain and the octapeptid motif. PD, paired DNA-binding domain (amino acids 16-142); O, octapeptide (aa 179-186); H, homeodomain (aa 228-254); TA, transactivation domain (aa 304-391); I, inhibitory domain (aa 359-391).

Figure 2.

Genetic features of patients with PAX5AMP. (A) Data for the 77 patients with intragenic amplification of PAX5 identified at diagnosis. The copy numbers for each PAX5 exon and the other genes targeted by the P335 IKZF1 MLPA kit are shown. Cytogenetic results were available for 57 patients, with abnormalities involving the short arm of chromosome 9, trisomy 5, and monosomy 7 being the most common recurrent chromosomal abnormalities. †In patient 31, the probe ratio values for exons 2 and 5 were just below the cutoff of 2 for ≥4 copies; because the percentage of blast cells was low at 83.5%, this result was interpreted as amplification. ‡In patient 69, MLPA showed that exon 2 had a ratio of 2.42 and exon 5 of 1.69; however on the single-nucleotide polymorphism array, exons 2 to 5 were amplified. (B) Data from 9 matched diagnosis-relapse pairs. *In patient 37, the difference in copy number of the amplified exons between diagnosis and relapse was due to reduced percentage of blasts at relapse. **P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion assessed by MLPA, FISH, and/or reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. ***Patient 16 presented with partial trisomy of chromosome 5 as a result of an unbalanced translocation involving chromosomes 1 and 5: 47,XY,der(1)(1qter-1p21::5q?34-5qter),+der(5)(5pter-5q15::1p21-1pter).

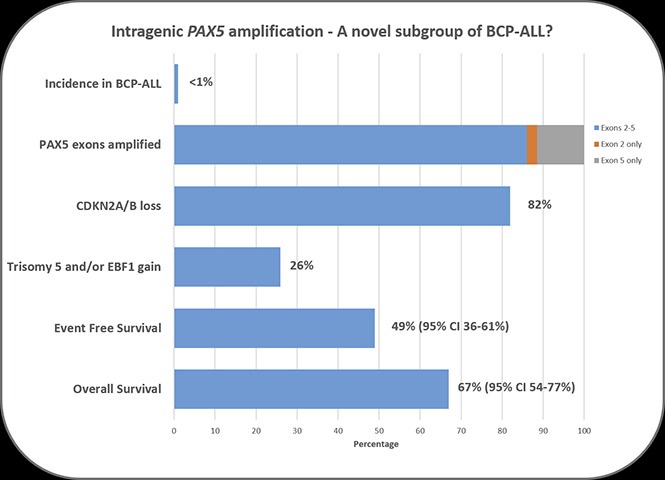

Although sporadic cases with PAX5AMP have been previously reported,3,4,16,17 here we show PAX5AMP to be a recurrent abnormality, occurring in 52 of 5535 patients from population-based cohorts (∼1% of BCP-ALL and 3% of the B-other subgroups [33 of 1271] supplemental Table 2). The remaining 27 patients were recruited individually to this study. Apart from 1 patient case with BCR-ABL1 fusion, PAX5AMP was mutually exclusive of other major risk-stratifying cytogenetic markers,1 including IGH, PDGFRB/CSF1R, ABL1, ABL2, JAK2, and ZNF384 rearrangements, among 24 patient cases tested by FISH (data not shown).

Among the other genes assessed by MLPA, CDKN2A/B loss was the most common abnormality associated with PAX5AMP (82%), higher than in other BCP-ALL subgroups.3,18 Gain of EBF1 (26%), deletion of IKZF1 (13%), and deletion of the PAR1 region resulting in P2RY8-CRLF2 fusion (10%) were other common alterations, suggesting a collaborative role in PAX5AMP leukemia development.

Consistent with the MLPA data, chromosomal abnormalities involving chromosome arm 9p (26%), trisomy 5 (23%), and monosomy 7 (12%) were observed among patients with successful karyotypes (n = 57; supplemental Table 3). Notably, trisomy 5 is a rare finding in BCP-ALL in the absence of high hyperdiploidy. Our previous study of trisomy 5 as the sole cytogenetic abnormality suggested an association with poor prognosis.19

The main demographic and clinical features of the 77 patients with PAX5AMP identified at diagnosis were male predominance (66%), age >10 years (25%), white blood cell count (WBC) ≥50 × 109 (39%), and National Cancer Institute high-risk status (55%). Minimal residual disease (MRD) data were available for 45 patients. Among ALL2003 patients with evaluable MRD (n = 8), 50% were positive at day 28 (>0.01%). Among patients treated in ALL-BFM 2000 with MRD data (n = 14), 12 were classified as MRD intermediate risk and 1 each as high and low risk, whereas all European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer patients (n = 10) were intermediate risk, apart from 1 classified as high risk. From these limited data, we cannot assign an association between PAX5AMP and MRD.

Among 74 patients with complete remission data available, 73 achieved complete remission by end of induction; 1 patient died before therapy. Relapse occurred in 40% (29 of 73) of these patients. The site of relapse, known for 22 patients, was isolated bone marrow (n = 16), extramedullary (n = 3), or combined relapse (n = 3). The time to relapse (median, 2.1 years) was known for 25 patients, with a ratio of very early to early to late relapse of 9:10:6, classifying 15 (55%) as high risk according to current criteria.20 Among patients experiencing relapse with sufficiently long follow-up, 17 (59%) died (relapse, n = 9; infection in remission, n = 3; unknown, n = 5), and 10 remained alive >3 years postrelapse.

The 5-year EFS and OS rates, evaluable for 74 patients, were 49% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36%-61%) and 67% (95% CI, 54%-77%), respectively. To identify risk factors, we examined the effects of age, WBC, National Cancer Institute status, year of diagnosis, and presence of additional genetic abnormalities, but only WBC was significant. Patients with a WBC >50 × 109/L had a significantly increased risk of death (hazard ratio, 3.48; 95% CI, 1.46-8.32; P = .005). In context, these low survival rates were generated from patients diagnosed over a 22-year period (1993-2015), treated according to a wide range of trial protocols, highlighting the need for prospective studies.

The clinical, genetic, and outcome profiles of patients with PAX5AMP were distinct from those harboring PAX5 deletions, which occur at different incidences between BCP-ALL subgroups.3 Although present at an increased frequency in high-risk ALL, PAX5 deletions are not associated with an inferior outcome.21,22 Because the number of patients with BCP-ALL with distinct PAX5 fusions is limited, their prognostic relevance remains to be determined.

In conclusion, we have identified a rare subset of patients with BCP-ALL with PAX5AMP, who share a distinct spectrum of genetic abnormalities, including high frequencies of CDKN2A/B loss and trisomy 5. A majority of these patients lack established cytogenetic abnormalities, suggesting that PAX5AMP may define a distinct subtype of BCP-ALL. Although several patients presented with P2RY8-CRLF2 and 1 with BCR-ABL1, both have been reported as secondary changes occurring alongside primary genetic abnormalities.3,23,24 Where matched diagnosis and relapse samples were available, the same amplification was present at both time points, indicating that PAX5AMP may be an important driver of leukemogenesis. Because patients with PAX5AMP showed a high incidence of relapse, we recommend testing for PAX5AMP in future ALL trials to determine its true prognostic impact.

Supplementary Material

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Bloodwise (formerly Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research) and the Anniversary Fund of the Austrian National Bank (OeNB grant 14133) (K.N.). M.Z., E.F., and J. Trka are supported by NV15-30626A and 00064203 (FN Motol). E.W. is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (KUN2012-5366). R.S. is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Australia (APP1057746). M.L.d.B. and J.M.B. are supported by the KiKa Foundation (Kinderen Kankervrij) and the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under the project European Network for Cancer Research in Children and Adolescents (ENCCA; grant agreement HEALTH-F2-2011-261474). A.P. was supported by the National Center of Research and Development (LIDER grant 031/635/l-5/13/NCBR/2014). H.C. and C.L. were supported by the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) ERA-NET on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN) project TRANSCALL. R.K.-S. is supported by the German Childhood Cancer Foundation (grant DKS 2011.14). G.C. and G.F. are supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC).

Authorship

Contribution: C.S., K.N., S.S., and C.J.H. designed the study; C.S., L.C., K.N., S.S., C.J.H., and A.V.M. analyzed and interpreted data; the remaining authors provided genetic and clinical data; and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for E.W. and R.P.K. is Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

A list of the members of the International Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (I-BFM) Study Group appears on the I-BFM website (https://bfminternational.wordpress.com/).

Correspondence: Sabine Strehl, Children’s Cancer Research Institute, St Anna Kinderkrebsforschung, Zimmermannplatz 10, 1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: sabine.strehl@ccri.at; and Christine J. Harrison, Leukaemia Research Cytogenetics Group, Wolfson Childhood Cancer Research Centre, Northern Institute for Cancer Research, Newcastle University, Level 6, Herschel Building, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE1 7RU, United Kingdom; e-mail: christine.harrison@newcastle.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Moorman AV. The clinical relevance of chromosomal and genomic abnormalities in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Blood Rev. 2012;26(3):123-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medvedovic J, Ebert A, Tagoh H, Busslinger M. Pax5: a master regulator of B cell development and leukemogenesis. Adv Immunol. 2011;111:179-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwab CJ, Chilton L, Morrison H, et al. Genes commonly deleted in childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: association with cytogenetics and clinical features. Haematologica. 2013;98(7):1081-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446(7137):758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):125-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah S, Schrader KA, Waanders E, et al. A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1226-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auer F, Rüschendorf F, Gombert M, et al. Inherited susceptibility to pre B-ALL caused by germline transmission of PAX5 c.547G>A. Leukemia. 2014;28(5):1136-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyaud E, Struski S, Prade N, et al. Wide diversity of PAX5 alterations in B-ALL: a Groupe Francophone de Cytogenetique Hematologique study. Blood. 2010;115(15):3089-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nebral K, Denk D, Attarbaschi A, et al. Incidence and diversity of PAX5 fusion genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(1):134-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurahashi S, Hayakawa F, Miyata Y, et al. PAX5-PML acts as a dual dominant-negative form of both PAX5 and PML. Oncogene. 2011;30(15):1822-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortschegger K, Anderl S, Denk D, Strehl S. Functional heterogeneity of PAX5 chimeras reveals insight for leukemia development. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(4):595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fazio G, Cazzaniga V, Palmi C, et al. PAX5/ETV6 alters the gene expression profile of precursor B cells with opposite dominant effect on endogenous PAX5. Leukemia. 2013;27(4):992-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krentz S, Hof J, Mendioroz A, et al. Prognostic value of genetic alterations in children with first bone marrow relapse of childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(2):295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Veer A, Waanders E, Pieters R, et al. Independent prognostic value of BCR-ABL1-like signature and IKZF1 deletion, but not high CRLF2 expression, in children with B-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122(15):2622-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwab CJ, Jones LR, Morrison H, et al. Evaluation of multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification as a method for the detection of copy number abnormalities in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49(12):1104-1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Familiades J, Bousquet M, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, et al. PAX5 mutations occur frequently in adult B-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and PAX5 haploinsufficiency is associated with BCR-ABL1 and TCF3-PBX1 fusion genes: a GRAALL study. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):1989-1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ofverholm I, Tran AN, Heyman M, et al. Impact of IKZF1 deletions and PAX5 amplifications in pediatric B-cell precursor ALL treated according to NOPHO protocols. Leukemia. 2013;27(9):1936-1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sulong S, Moorman AV, Irving JA, et al. A comprehensive analysis of the CDKN2A gene in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia reveals genomic deletion, copy number neutral loss of heterozygosity, and association with specific cytogenetic subgroups. Blood. 2009;113(1):100-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris RL, Harrison CJ, Martineau M, Taylor KE, Moorman AV. Is trisomy 5 a distinct cytogenetic subgroup in acute lymphoblastic leukemia? Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148(2):159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhojwani D, Pui CH. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):e205-e217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorman AV, Enshaei A, Schwab C, et al. A novel integrated cytogenetic and genomic classification refines risk stratification in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(9):1434-1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. ; Children’s Oncology Group. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):470-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dun KA, Vanhaeften R, Batt TJ, Riley LA, Diano G, Williamson J. BCR-ABL1 gene rearrangement as a subclonal change in ETV6-RUNX1–positive B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2016;1(2):132-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morak M, Attarbaschi A, Fischer S, et al. Small sizes and indolent evolutionary dynamics challenge the potential role of P2RY8-CRLF2-harboring clones as main relapse-driving force in childhood ALL. Blood. 2012;120(26):5134-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.