Abstract

Problem

Women with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) are at risk for pregnancy complications despite treatment with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or aspirin (ASA). aPL recognizing beta2 glycoprotein I can target the uterine endothelium, however, little is known about its response to aPL. This study characterized the effect of aPL on human endometrial endothelial cells (HEECs), and the influence of LMWH and ASA.

Method of Study

HEECs were exposed to aPL or control IgG, with or without low dose LMWH and ASA, alone or in combination. Chemokine and angiogenic factor secretion was measured by ELISA. A tube formation assay was used to measure angiogenesis.

Results

aPL increased HEEC secretion of pro-angiogenic VEGF and PlGF; increased anti-angiogenic sFlt-1; inhibited basal secretion of the chemokines MCP-1, G-CSF and GRO-α; and impaired angiogenesis. LMWH and ASA, alone and in combination, exacerbated the aPL-induced changes in the HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine profile. There was no reversal of the aPL-inhibition of HEEC angiogenesis by either single or combination therapy.

Conclusions

By aPL inhibiting HEEC chemokine secretion and promoting sFlt-1 release, the uterine endothelium may contribute to impaired placentation and vascular transformation. LMWH and ASA may further contribute to endothelium dysfunction in women with obstetric APS.

Keywords: Endothelium, Pregnancy, Antiphospholipid Antibody, Angiogenic, Chemokine

Introduction

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an acquired autoimmune thrombophilia characterized by the presence of at least one of three types of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL): anti-cardiolipin; anti-beta2 glycoprotein I (β2GPI); and lupus anticoagulant. Systemic manifestations of this disease are a hyper-coaguable state which leads to increased risk of recurrent venous or arterial thrombosis. In women, recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is a hallmark of obstetric APS. During pregnancy, women with APS are at further increased risk of uteroplacental insufficiency, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and preeclampsia1, 2. Furthermore, women with anti-β2GPI antibodies are at highest risk of fetal and late-term complications because the placental trophoblast synthesizes and expresses β2GPI, making this organ a specific target for aPL3–6.

Pregnant women with APS are routinely treated with low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), either alone or in combination with acetyl-salicylic acid (aspirin, ASA), with practice varying amongst physicians7. Studies regarding each medication’s effectiveness for preventing RPL in the setting of aPL are controversial8–12, especially in light of histological studies which confirm inflammation rather than intraplacental thrombosis at the maternal-fetal interface6. Moreover, despite treatment, pregnant patients with APS continue to have high rates of preeclampsia and preterm birth13–16. Experimental studies have further confirmed the lack of thrombosis, and instead demonstrated inflammation and placental insufficiency as the underlying pathogenesis for obstetric APS17–20. Thus, any beneficial effects of LMWH may be through mechanisms distinct of its anticoagulant properties18, 21–23. The majority of human in vitro studies have focused on how aPL impact the placental trophoblast. Anti-β2GPI aPL induce a pro-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, and anti-migratory profile in trophoblast cells, leading to their diminished ability to interact with and replace the endothelial cells found within the uterine spiral arteries18–20. Furthermore, a role for the innate immune Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in initiating aPL-induced trophoblast inflammation has been demonstrated22.

The serum glycoprotein, β2GPI, localizes not only to the placental trophoblast but also to the uterine endothelium4. As result, aPL recognizing β2GPI can also affect the maternal side of the utero-placental interface by binding directly to the endometrial endothelial cells24–26; the same cells that the trophoblast interacts with and replaces during normal spiral artery transformation27. However, much about the action of aPL on these human endometrial endothelial cells (HEECs) is still unclear. Most aPL-endothelial interactions have been studied using fetus-derived human endothelial cells from umbilical veins (HUVECs) as a model for systemic vascular events in APS. Similar to findings in the trophoblast22, aPL recognizing β2GPI are able to bind HUVEC TLR4, activate the TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway28–30, and induce an inflammatory cytokine/chemokine response29, 31. The objective of this study was to elucidate the influence that anti-β2GPI aPL have on the maternal uterine vasculature using human endometrial endothelial cells (HEECs), and to investigate the role of TLR4. This study also sought to evaluate the current therapeutic strategy of LMWH and ASA in counteracting any influences aPL had on HEEC function.

Materials & Methods

Reagents

Sterile low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (enoxaparin sodium injection; 100mg/ml), was purchased from Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Bridgewater, NJ). Acetyl-salicylic acid (ASA) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), reconstituted in ethanol, and filter-sterilized prior to use. Ethanol alone was included as a vehicle control for ASA. The TLR4 antagonist, LPS-RS (Lipopolysaccharide isolated from Rhodobacter sphaeroides), was purchased from Invivogen (San Diego, CA).

Human endothelial cells

The human endometrial endothelial cells (HEECs) used in this study were originally isolated from the microvasculature of cycling endometrium of multiple women, and all stages of cycles were pooled. The primary cells were characterized to express a range of adhesion molecules and endothelial markers, and to form endothelial tubes when seeded in Matrigel. Subsequently these cells were telomerase immortalized and have been characterized to express the same markers and function as the primary cells32–36. Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Yale University’s tissue culture core laboratory37. Cell culture was performed as previously described32, 35 and both cell types were cultured in Endothelial Basal Medium-2 (EBM-2) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Lonza; Allendale, NJ).

Antiphospholipid antibodies

This study used the aPL, IIC5, which is a mouse IgG1 anti-human β2GP1 monoclonal antibody. This aPL has been previously characterized. Like patient-derived polyclonal aPL, IIC5 binds β2GPI when it is immobilized on a negatively charged surface such as phospholipids, cardiolipin, phosphatidyl serine or irradiated polystyrene38. IIC5 also has pronounced lupus anticoagulant activity and thus represents a triple positive aPL39. IIC5 reacts specifically with an epitope within domain V of β2GPI, which may be more important than domain I binding aPL for pregnancy morbidity in APS patients40. Moreover, IIC5 binds to human first trimester extravillous trophoblast cells3, 22, 41, and alters their function in a similar fashion to patient-derived polyclonal aPL-IgG42, and polyclonal IgG aPL recognizing β2GPI22, 43. Mouse IgG1 clone 107.3 (BD Biosciences) was used as an isotype control.

Angiogenic factor and chemokine studies

HEECs (5×105) or HUVECs (5×105) were plated in 60mm tissue culture plates pre-coated with 2% gelatin in EBM-2 media supplemented with 2% FBS. The next day the media was replaced and the cells treated. HEECs or HUVECs were treated for 72hrs with either no treatment (NT), aPL (60 μg/ml) or control IgG (60μg/ml) to establish the baseline effect of aPL. The aPL dose was determined by preliminary dose response experiments (data not shown) and are similar to other studies26. To study the role of TLR4, HEECs were treated for 72hrs with NT or aPL in the presence of either media or LPS-RS (10μg/mL). To study the effect of current therapeutics on HEEC responses to aPL, cells were treated for 72hrs with NT, LMWH (10μg/ml), ASA (10μg/ml) or both LMWH and ASA (each at 10μg/ml) in the presence of either media or aPL (60μg/ml). The concentrations of ASA and LMWH used in this study were based on a previous study, and equivalent to low dose medications used in the clinical setting23. After treatment, cell-free supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C. Supernatants were then measured by ELISA and/or multiplex analysis. The pro-angiogenic factors: vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF); and the anti-angiogenic factors: soluble FMS-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and soluble endoglin (sEndoglin) were measured by ELISA (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN). The chemokines, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1/CCL2) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF/CSF3) were also measured by ELISA (R&D Systems). Multiplex analysis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was performed for the following analytes as previously described44: interleukin (IL)-1β; IL-6; IL-8 (CXCL8); IL-10; IL-12 (p70); IL-17; growth-regulated oncogene-alpha (GRO-α/CXCL1); granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF/CSF2); interferon gamma (IFN γ); IFNγ -inducible protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10); macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha (MIP-1α/CCL3); MIP-1β (CCL4); Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted (RANTES/CCL5) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα). ELISA was used for subsequent measurements of IL-8 (Assay Designs/Enzo Life Sciences; Farmingdale, NY, USA) and GRO-α (R&D Systems). All factors were detected within the range of the assays.

Angiogenesis assay

An endothelial tube formation assay was used to measure angiogenesis as previously described24, 25. HEECs (5×104) were seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates over undiluted reduced growth factor Matrigel (BD-Biosciences; San Jose, CA) with or without aPL (60μg/ml) or control IgG (60μg/ml). In separate experiments, HEECs were plated with NT, LMWH (10μg/ml), ASA (10μg/ml) or both LMWH and ASA (each at 10μg/ml) in the presence of either media or aPL (60μg/ml). Following an 8hr incubation, the formation of vessel tube-like structures was monitored by light microscopy (Carl-Zeiss Observer Z1). Four fields per well were recorded using OpenLab software (Perkin Elmer). The number of tubes per field were counted manually by two individuals, independently, and the two sets of data for each field were averaged.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times. All analyses were performed at least in duplicate. All data are reported as either mean ± SEM of pooled experiments for bar charts, or median and quartiles ± SD for box plots of pooled experiments. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and determined using Prism Software (Graphpad, Inc; La Jolla, CA). For normally distributed data, significance was determined using either one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple comparisons or a t-test. For data not normally distributed, significance was determined using a non-parametric multiple comparison test for multiple comparisons or the wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Results

aPL alter HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion

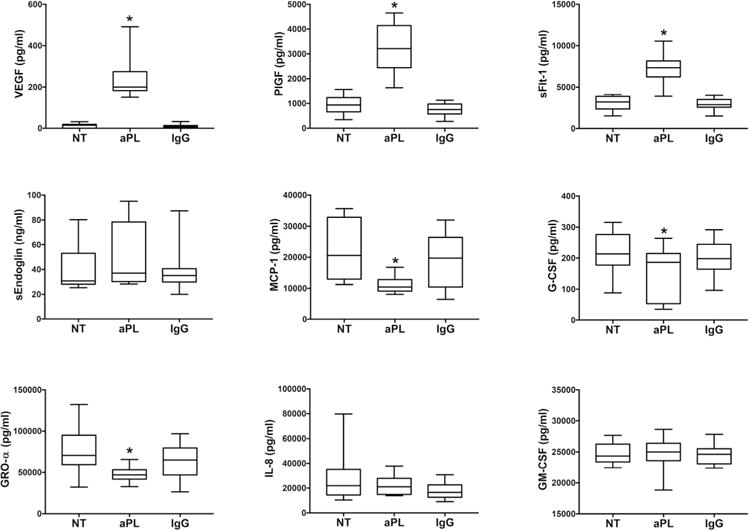

The first objective of this study was to measure the effects of aPL on the HEEC angiogenic and cytokine/chemokine factor profile. Compared to the no treatment (NT) control, aPL significantly increased HEEC secretion of: pro-angiogenic VEGF by 20.5±8.7-fold; pro-angiogenic PlGF by 3.7±0.8-fold; and anti-angiogenic sFlt-1 by 2.4±0.4-fold (Figure 1). The IgG control had no significant effect on HEEC secretion of VEGF, PlGF, or sFlt-1 (Figure 1). Neither aPL, nor the IgG control had any significant effect on HEEC production of sEndoglin compared to the NT control (Figure 1). Treatment of HEECs with aPL significantly reduced basal MCP-1 secretion by 44.8±7.3%; G-CSF by 31.0±12.8%; and GRO-α by 37.5±4.6% when compared to the NT control. The IgG control had no significant effect on HEEC secretion of MCP-1, G-CSF, or GRO-α (Figure 1). Neither aPL, nor the IgG control, had any significant effect on HEEC production of IL-8 or GM-CSF compared to the NT control (Figure 1), and all other factors tested by multiplex were below the assay’s detection limit (data not shown).

Figure 1. Effect of aPL on HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion.

HEECs were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG. Data are pooled from 9 independent experiments. Box plots show secreted levels of VEGF; PlGF; sFlt-1; sEndoglin; MCP-1; G-CSF; GRO-α; IL-8; and GM-CSF as determined by ELISA and multiplex analysis. *p<0.05 relative to the NT control.

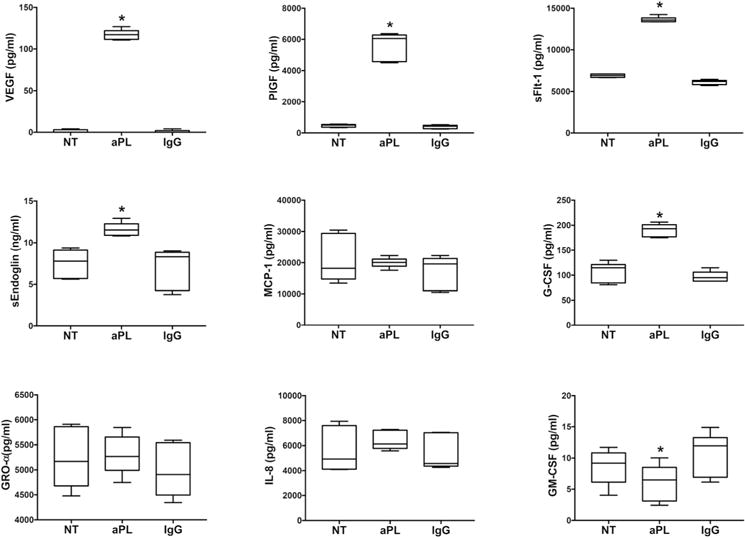

aPL induce a distinct angiogenic factor and chemokine profile in HUVECs

Since HUVECs are commonly used as a model for the study of the endothelium in APS28–31, we sought to determine if their response to aPL recognizing β2GPI was similar to the HEECs. Similar to the HEECs, aPL significantly increased HUVEC secretion of pro-angiogenic VEGF by 80.4±11.6-fold; pro-angiogenic PlGF by 12.1±0.3-fold; and anti-angiogenic sFlt-1 by 2.0±0.0-fold when compared to the NT control (Figure 2). The IgG control had no significant effect on HUVEC secretion of VEGF, PlGF or sFlt-1 (Figure 2). In contrast to the HEECs, aPL significantly increased HUVEC secretion of the anti-angiogenic sEndoglin by 1.6±0.2-fold compared to the NT control, while the IgG control had no effect (Figure 2). The aPL-modulated chemokine profile was also distinct. Compared to the NT control, aPL significantly increased HUVEC secretion of G-CSF by 1.8±0.2-fold and significantly reduced GM-CSF secretion by 28.0 ±20.4%, while the IgG control had no significant effect (Figure 2). Neither aPL, nor the IgG control, had any significant effect on HUVEC production of MCP-1, GRO-α or IL-8 compared to the NT control (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of aPL on HUVEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion.

HEECs were treated with no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. Box plots show secreted levels of VEGF; PlGF; sFlt-1; sEndoglin; MCP-1; G-CSF; GRO-α; IL-8; and GM-CSF as determined by ELISA. *p<0.05 relative to the NT control.

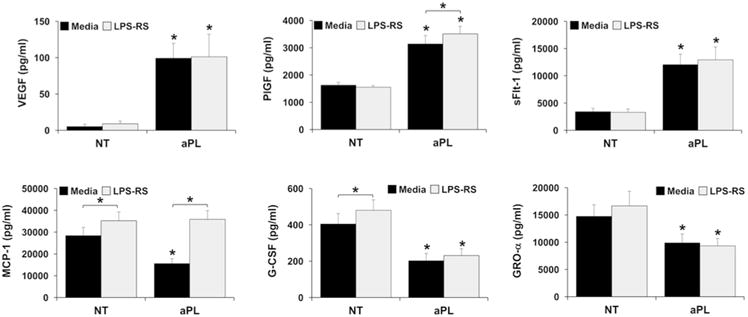

aPL inhibition of HEEC MCP-1 secretion is mediated by TLR4

Having established the HEEC angiogenic and chemokine profile induced by aPL, the next objective was to investigate the mechanism involved by blocking TLR4 function using the antagonist, LPS-RS. aPL-induced secretion of VEGF, PlGF and sFlt-1 was not reversed by the presence of LPS-RS, although aPL-induced PlGF was slightly yet significantly increased by 1.1±0.1-fold (Figure 3). While LPS-RS significantly increased basal MCP-1 levels by 1.3±0.0-fold, in the presence of aPL, MCP-1 levels were significantly increased by 2.4±0.1-fold, bringing levels back to baseline. Thus, the presence of LPS-RS, completely reversed the inhibition of HEEC MCP-1 secretion induced by aPL (Figure 3). Although LPS-RS slightly, yet significantly, increased basal G-CSF levels by 1.2±0.0-fold, there was no significant effect of LPS-RS on the aPL-mediated inhibition of G-CSF or GRO-α secretion by HEECs Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effect of TLR4 inhibition on aPL-induced HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion.

HEECs were treated with no treatment (NT) or aPL in the presence of media or LPS-RS. Supernatants were measured by ELISA for: VEGF; PlGF; sFlt-1; MCP-1; G-CSF; and GRO-α. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 relative to the matching NT control for each condition (media or LPS-RS) unless otherwise indicated.

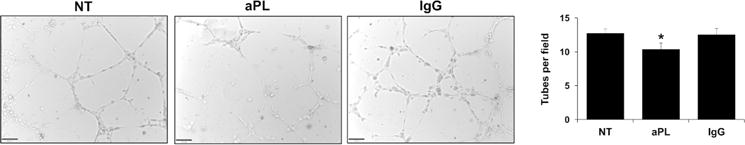

aPL inhibit HEEC angiogenesis

The next objective was to determine whether aPL affected vascular development. For this, an angiogenesis assay was utilized in which the formation of HEEC vessel tube-like structures in Matrigel was measured. When compared to the NT control, aPL significantly reduced the number of HEEC tubes formed by 19.1±9.9%, while the IgG control had no significant effect (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of aPL on HEEC tube formation.

HEECs were seeded on Matrigel-coated plates and treated with no treatment (NT), aPL, or control IgG. After 8hrs, tube-like vessels were imaged and quantitative analysis performed. Images are from one representative field of one representative experiment (magnification 10X). Barchart shows the number of tubes counted per field and pooled from 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 relative to the NT control.

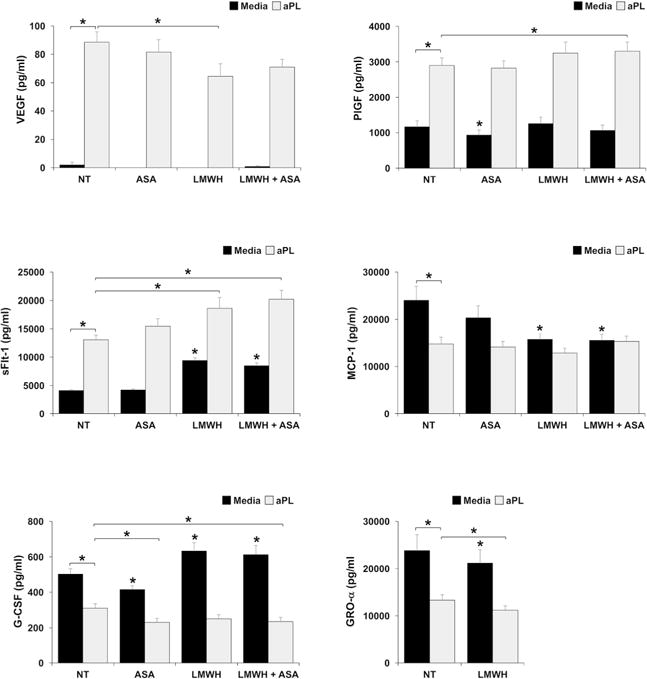

Effect of LMWH and ASA on HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion in the presence and absence of aPL

Since our understanding of the actions of LMWH and ASA in obstetric APS are incomplete, the effects of these therapies, alone and in combination, on HEEC function in the presence and absence of aPL were investigated. The findings are summarized in Table 1. As already determined, treatment of HEECs with aPL significantly increased VEGF, PlGF, and sFlt-1; and significantly inhibited MCP-1, G-CSF and GRO-α secretion compared to the NT/media control (Figure 5).

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of ASA and LMWH on HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion in the presence and absence of aPL.

| Baseline effect on HEECs | ASA | LMWH | LMWH + ASA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | sFlt-1, G-CSF | sFlt-1, G-CSF | |

| Decreased | PlGF, G-CSF | MCP-1, GRO-α | MCP-1 |

| No effect | VEGF, sFlt-1, MCP-1 | VEGF, PlGF | VEGF, PlGF |

| Effect on HEECS in presence of aPL | ASA | LMWH | LMWH + ASA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Further increased | sFlt-1 | sFlt-1, G-CSF | |

| Further decreased | G-CSF | VEGF, GRO-α | MCP-1 |

| No effect | VEGF, PlGF, sFlt-1, MCP-1 | PlGF, MCP-1, G-CSF | VEGF, MCP-1 |

Figure 5. Effect of ASA and LMWH on HEEC aPL-induced HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine secretion.

HEECs were treated no treatment (NT), ASA, LMWH or both (LMWH + ASA) in the presence of media or aPL. Supernatants were measured by ELISA for: VEGF; PlGF; sFlt-1; MCP-1; G-CSF; and GRO-α. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05 relative to the NT/media control unless otherwise indicated.

LMWH and ASA, either alone or in combination, had no effect on basal VEGF secretion. When compared to the NT/media control ASA alone significantly reduced basal PlGF by 19.8±3.8% and G-CSF by 16.4±4.3%. Compared to the NT/media control, LMWH alone, or in combination with ASA, significantly increased basal levels of HEEC sFlt-1 by 2.3±0.1-fold and 2.1±0.1-fold, respectively; increased basal levels of G-CSF by 1.3±0.1-fold and 1.2±0.1-fold, respectively; and decreased basal levels of MCP-1 by 31.3±5.0% and 31.3±6.5%, respectively. Compared to the NT/media control, LMWH alone significantly decreased basal levels of HEEC GRO-α secretion by 9.7±3.1% (Figure 5 & Table 1). Ethanol alone was run as a control for ASA and had no effect on any of the factors tested (data not shown), with the exception of GRO-α which was significantly inhibited by 25.9±8.1%. Thus, ASA, either alone or in combination with LMWH, was excluded from the GRO-α analysis.

LMWH alone significantly reduced the aPL-induced upregulation of HEEC VEGF secretion by 24.6±13.5%. However ASA, either alone or in combination, had no effect on VEGF production in the presence of aPL. LMWH in combination with ASA significantly augmented the aPL-induced upregulation of HEEC PlGF by 1.1±0.0-fold. However LMWH alone or ASA alone had no effect on PlGF production in the presence of aPL. LMWH either alone, or in combination with ASA, significantly augmented the aPL-induced upregulation of HEEC sFlt-1 by 1.4±0.1-fold and 1.6±0.1-fold, respectively, while ASA alone had no effect. LMWH and ASA, either alone or in combination, had no effect on the ability of aPL to reduce HEEC MCP-1 secretion. ASA either alone, or in combination with LMWH significantly and further reduced the aPL-mediated inhibition of HEEC G-CSF by 25.6±4.8% and 17.4±8.9%, respectively, while LMWH alone had no effect. LMWH alone further reduced the aPL-mediated inhibition of HEEC GRO-α secretion by 14.4±5.0% (Figure 5 & Table 1).

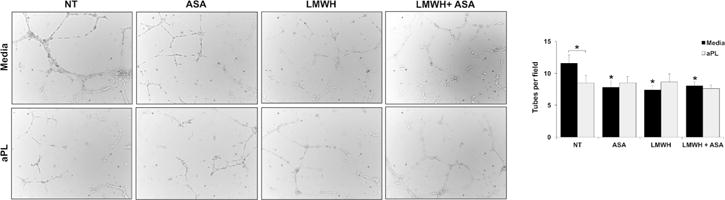

Effect of LMWH and ASA on HEEC angiogenesis in the presence and absence of aPL

When compared to the NT/media control, HEEC tube formation was significantly reduced by 27.9±15.1% in the presence of ASA alone, by 30.2±14.2% in the presence of LMWH alone, and by 24.1±14.5% in the presence of combination LMWH and ASA (Figure 6). The ethanol control had no effect on the basal HEEC tube formation (Data not shown). As already determined, treatment of HEECs with aPL significantly inhibited HEEC tube formation by 26.3±9.1% compared to the NT/media control. LMWH and ASA, either alone or in combination, had no additional effect on the numbers of HEEC tubes formed in the presence of aPL (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effect of ASA and LMWH on HEEC tube formation in the presence and absence of aPL.

HEECs were seeded on Matrigel-coated plates and treated with no treatment (NT), ASA, LMWH or both (LMWH + ASA) in the presence of media or aPL. After 8hrs, tube-like vessels were imaged and quantified. Images are from one representative field of one representative experiment (magnification 10X). Barchart shows the number of tubes counted per field and pooled from 4 independent experiments. *p<0.05 relative to the NT/media control unless otherwise indicated.

Discussion

Obstetric APS, once thought of as a thrombotic disease, is now known to be inflammatory in origin and associated with placental insufficiency and reduced vascular development and remodeling6. One major way in which aPL negatively impact pregnancy is by targeting the placenta; altering trophoblast function18–20. During pregnancy, aPL recognizing β2GPI can also affect the maternal side of the interface by binding directly to the uterine endothelium4, 24–26, which provides the scaffolding upon which trophoblast cells transform the maternal spiral arteries27. However, little is known about how aPL influence the function of these human endometrial endothelial cells (HEECs). Furthermore, little is known about the impact the current therapeutics for obstetric APS have on HEEC function. Herein, we report that aPL modulates HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine production, in part through TLR4 activation, and disrupts angiogenesis. Furthermore, LMWH and ASA, in general, exacerbates rather than protects against these aPL-mediated changes in HEEC function.

Previous studies found that aPL inhibit HEEC VEGF secretion; STAT3 phosphorylation; NFκB activity; and their ability to form vessel tube-like structures in vitro24–26. However, little else is known about their responses to aPL or the mechanisms involved. What these studies did highlight was a role for domain V of β2GPI since the peptide TIFI, that shares homology with the aPL-binding site of domain V, blocked these responses26. In our current study, using an aPL that binds to domain V of β2GPI40, we found that HEEC pro-angiogenic (VEGF, PlGF) and anti-angiogenic factor production (sFlt-1) was augmented, while basal chemokine secretion (MCP-1, G-CSF, GRO-α) was inhibited. In addition, HEEC angiogenesis was inhibited.

While anti-angiogenic sFlt-1 is associated with promoting hypertension and proteinuria in preeclampsia45, there is also evidence that sFlt-1 contributes to poor placentation by impairing endothelial function, impacting uterine vessel remodeling46, 47, and blocking the action of VEGF and PlGF, which promote trophoblast differentiation and invasion48, and angiogenesis49–51. Thus, although HEEC production of pro-angiogenic VEGF and PIGF were also increased, the elevated sFlt-1 response may contribute to the impaired HEEC angiogenesis that we, and others24–26, have observed. Moreover, the aPL-induced upregulation of HEEC VEGF production may drive the sFlt-1 response51. The differences in our studies demonstrating elevated HEEC VEGF secretion in response to aPL, while Di Simone’s group showed a reduction in this pro-angiogenic factor, may be explained by differences in culture conditions or in the use of our monoclonal domain V aPL compared to their use of polyclonal aPL24, 25.

In this study we also found that aPL suppressed HEEC secretion of chemokines that promote trophoblast invasion (G-CSF)52, and recruit macrophages and natural killer cells (MCP-1, GRO-α) that are necessary for normal spiral artery remodeling53–56. This data suggests that aPL may contribute to the shallow trophoblast invasion and disrupted spiral artery transformation seen in obstetric APS6 by directly impacting the uterine endothelium, in addition to targeting the placental trophoblast57, 58. Furthermore, we observed that under basal conditions, in general, HEECs produced higher levels of chemokines compared to the angiogenic factors. This may reflect the normal function of uterine endothelial cells in playing an important role in immune cell recruitment at the maternal-fetal interface for successful vascular remodeling59. Our studies also highlight that being of fetal origin, and generating a distinct angiogenic and chemokine profile in response to aPL, HUVECs may not be the best model for studying the endothelium in either systemic or obstetric APS.

A role for TLR4 has been demonstrated in aPL-mediated thrombosis60, 61, and in aPL-mediated trophoblast inflammation22. In studies using HUVECs, β2GPI interacts directly with TLR4 and mediates aPL-induced endothelial cell activation28–30, 62. HEECs express functional TLRs, including TLR436. In this current study, TLR4 was found to mediate the aPL-induced suppression of HEEC MCP-1 secretion, but was not involved in any of the other responses tested, suggesting a role for additional cell surface receptors that aPL may recruit. These could include TLR263 or ApoER264

LMWH is commonly used as anti-coagulant treatment in systemic APS, and early initiation of aspirin (prior to 16 weeks of gestation) is thought to be beneficial for fetal development65. Both therapies are given empirically to women with recurrent miscarriage, whether it is due to APS or not13, 66, 67. In women with aPL, while LMWH, either alone or in combination with aspirin has been shown to decrease rates of fetal loss, results are conflicting8–12. Furthermore, despite treatment, women with APS continue to have high rates of late gestational complications13–16. Given these controversies, we sought to elucidate the action of LMWH and ASA either alone or in combination on HEEC function in the absence and presence of aPL.

In the absence of aPL, LMWH and ASA, alone and in combination, induced potentially detrimental angiogenic and chemokine effects on HEECs, somewhat akin to aPL treatment. Similar to what has been found in the trophoblast18, 23, 43, 68, LMWH induced the release of sFlt-1, confirming this observation in endothelial cells from other sources69. LMWH also reduced HEEC angiogenesis, potentially as a consequence of the overwhelming sFlt-1 release46, 47, which again has been observed in other endothelial cell types69. Interestingly, ASA had a similar effect by inhibiting HEEC tube formation, an observation also seen in HUVECs49, 50. As a result, combination LMWH and ASA increased HEEC sFlt-1 release and limited angiogenesis. Both single and combination therapies also reduced basal HEEC chemokine production. This may be because LMWH can act through non-thrombotic pathways, by inhibiting inflammation21–23; and ASA is an anti-inflammatory agent70, 71.

In the context of aPL, LMWH alone further augmented aPL-induced HEEC sFlt-1 release; further reduced GRO-α secretion; and reduced aPL-induced VEGF; while ASA alone further reduced HEEC G-CSF secretion. In combination, LMWH and ASA further augmented aPL-induced HEEC sFlt-1 and PlGF release; and further reduced G-CSF secretion. Thus, the net effect of LMWH and ASA was the exacerbation of aPL-induced changes in the HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine profile. Additionally, there was no reversal of the aPL-inhibition of HEEC angiogenesis by either single or combination therapy.

In summary, HEECs produce a number of chemokines and pro-angiogenic factors that may promote trophoblast invasion, immune cell recruitment, and spiral artery remodeling, in order to establish the adequate placentation and vascular development needed for a healthy pregnancy. aPL dysregulate this HEEC angiogenic factor and chemokine profile, and limit angiogenesis. Thus, the uterine endothelium may contribute to impaired placentation and vascular transformation seen in women with obstetric APS. LMWH and ASA, either alone or in combination, may further contribute to endothelial dysfunction in the setting of aPL, which may explain the inability of current therapies to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with APS.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the American Heart Association (#15GRNT24480140; to VMA). ZCQ was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR000141. EB was supported by a Senior Research Fellowship from Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

References

- 1.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, Derksen RH, PG DEG, Koike T, Meroni PL, Reber G, Shoenfeld Y, Tincani A, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Krilis SA. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreoli L, Chighizola CB, Banzato A, Pons-Estel GJ, Ramire de Jesus G, Erkan D. Estimated frequency of antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with pregnancy morbidity, stroke, myocardial infarction, and deep vein thrombosis: a critical review of the literature. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:1869–1873. doi: 10.1002/acr.22066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamley LW, Allen JL, Johnson PM. Synthesis of beta2 glycoprotein 1 by the human placenta. Placenta. 1997;18:403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agostinis C, Biffi S, Garrovo C, Durigutto P, Lorenzon A, Bek A, Bulla R, Grossi C, Borghi MO, Meroni P, Tedesco F. In vivo distribution of beta2 glycoprotein I under various pathophysiologic conditions. Blood. 2011;118:4231–4238. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meroni PL, Raschi E, Grossi C, Pregnolato F, Trespidi L, Acaia B, Borghi MO. Obstetric and vascular APS: same autoantibodies but different diseases? Lupus. 2012;21:708–710. doi: 10.1177/0961203312438116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viall CA, Chamley LW. Histopathology in the placentae of women with antiphospholipid antibodies: A systematic review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:446–471. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laskin CA, Spitzer KA, Clark CA, Crowther MR, Ginsberg JS, Hawker GA, Kingdom JC, Barrett J, Gent M. Low molecular weight heparin and aspirin for recurrent pregnancy loss: results from the randomized, controlled HepASA Trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:279–287. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080763). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohn DM, Goddijn M, Middeldorp S, Korevaar JC, Dawood F, Farquharson RG. Recurrent miscarriage and antiphospholipid antibodies: prognosis of subsequent pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2208–2213. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson MD, Ballem PJ, Tsang P, Purkiss S, Ensworth S, Houlihan E, Ensom MH. Treatment of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) in pregnancy: a randomized pilot trial comparing low molecular weight heparin to unfractionated heparin. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:729–734. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30644-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farquharson RG, Quenby S, Greaves M. Antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy: a randomized, controlled trial of treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:408–413. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Empson M, Lassere M, Craig JC, Scott JR. Recurrent pregnancy loss with antiphospholipid antibody: a systematic review of therapeutic trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattison NS, Chamley LW, Birdsall M, Zanderigo AM, Liddell HS, McDougall J. Does aspirin have a role in improving pregnancy outcome for women with the antiphospholipid syndrome? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1008–1012. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Backos M, Rai R, Baxter N, Chilcott IT, Cohen H, Regan L. Pregnancy complications in women with recurrent miscarriage associated with antiphospholipid antibodies treated with low dose aspirin and heparin. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branch DW, Khamashta MA. Antiphospholipid syndrome: obstetric diagnosis, management, and controversies. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1333–1344. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jesus GR, Rodrigues G, de Jesus NR, Levy RA. Pregnancy morbidity in antiphospholipid syndrome: what is the impact of treatment? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:403. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abheiden CN, Blomjous BS, Kroese SJ, Bultink IE, Fritsch-Stork RD, Lely AT, de Boer MA, de Vries JI. Low-molecular-weight heparin and aspirin use in relation to pregnancy outcome in women with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome: A cohort study. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2017;36:8–15. doi: 10.1080/10641955.2016.1217337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon JE, Girardi G. Antiphospholipid antibodies and pregnancy loss: a disorder of inflammation. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;77:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong M, Viall CA, Chamley LW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the placenta: a systematic review of their in vitro effects and modulation by treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:97–118. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pantham P, Abrahams VM, Chamley LW. The role of anti-phospholipid antibodies in autoimmune reproductive failure. Reproduction. 2016;151:R79–90. doi: 10.1530/REP-15-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahams VM, Chamley LW, Salmon JE. Antiphospholipid Syndrome and Pregnancy: Pathogenesis to Translation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 doi: 10.1002/art.40136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girardi G, Redecha P, Salmon JE. Heparin prevents antiphospholipid antibody-induced fetal loss by inhibiting complement activation. Nat Med. 2004;10:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nm1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Giles I, Pericleous C, Rahman A, Joyce SK, Panda B, Paidas MJ, Abrahams VM. Antiphospholipid antibodies induce a pro-inflammatory response in first trimester trophoblast via the TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;62:96–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han CS, Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Paidas MJ, Lockwood CJ, Abrahams VM. Aspirin and heparin effect on basal and antiphospholipid antibody modulation of trophoblast function. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1021–1028. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823234ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Ippolito S, Marana R, Di Nicuolo F, Castellani R, Veglia M, Stinson J, Scambia G, Di Simone N. Effect of Low Molecular Weight Heparins (LMWHs) on antiphospholipid Antibodies (aPL)-mediated inhibition of endometrial angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Simone N, Di Nicuolo F, D’Ippolito S, Castellani R, Tersigni C, Caruso A, Meroni P, Marana R. Antiphospholipid antibodies affect human endometrial angiogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:212–219. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.083410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Simone N, D’Ippolito S, Marana R, Di Nicuolo F, Castellani R, Pierangeli SS, Chen P, Tersigni C, Scambia G, Meroni PL. Antiphospholipid antibodies affect human endometrial angiogenesis: protective effect of a synthetic peptide (TIFI) mimicking the phospholipid binding site of beta(2) glycoprotein I. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:299–308. doi: 10.1111/aji.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris LK. Review: Trophoblast-vascular cell interactions in early pregnancy: how to remodel a vessel. Placenta. 2010;31(Suppl):S93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raschi E, Chighizola CB, Grossi C, Ronda N, Gatti R, Meroni PL, Borghi MO. beta2-glycoprotein I, lipopolysaccharide and endothelial TLR4: three players in the two hit theory for anti-phospholipid-mediated thrombosis. J Autoimmun. 2014;55:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raschi E, Testoni C, Bosisio D, Borghi MO, Koike T, Mantovani A, Meroni PL. Role of the MyD88 transduction signaling pathway in endothelial activation by antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood. 2003;101:3495–3500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen KL, Fonseca FV, Betapudi V, Willard B, Zhang J, McCrae KR. A novel pathway for human endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid/anti-beta2 glycoprotein I antibodies. Blood. 2012;119:884–893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meroni PL, Raschi E, Testoni C, Parisio A, Borghi MO. Innate immunity in the antiphospholipid syndrome: role of toll-like receptors in endothelial cell activation by antiphospholipid antibodies. Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schatz F, Soderland C, Hendricks-Munoz KD, Gerrets RP, Lockwood CJ. Human endometrial endothelial cells: isolation, characterization, and inflammatory-mediated expression of tissue factor and type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:691–697. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.3.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krikun G, Mor G, Huang J, Schatz F, Lockwood CJ. Metalloproteinase expression by control and telomerase immortalized human endometrial endothelial cells. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:719–724. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aldo PB, Krikun G, Visintin I, Lockwood C, Romero R, Mor G. A novel three-dimensional in vitro system to study trophoblast-endothelium cell interactions. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:98–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krikun G, Potter JA, Abrahams VM. Human Endometrial Endothelial Cells Generate Distinct Inflammatory and Antiviral Responses to the TLR3 agonist, Poly(I:C) and the TLR8 agonist, viral ssRNA. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;70:190–198. doi: 10.1111/aji.12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krikun G, Trezza J, Shaw J, Rahman M, Guller S, Abrahams VM, Lockwood CJ. Lipopolysaccharide appears to activate human endometrial endothelial cells through TLR-4-dependent and TLR-4-independent mechanisms. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2012;68:233–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2012.01164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw J, Tang Z, Schneider H, Salje K, Hansson SR, Guller S. Inflammatory processes are specifically enhanced in endothelial cells by placental-derived TNF-alpha: Implications in preeclampsia (PE) Placenta. 2016;43:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chamley LW, Konarkowska B, Duncalf AM, Mitchell MD, Johnson PM. Is interleukin-3 important in antiphospholipid antibody-mediated pregnancy failure? Fertil Steril. 2001;76:700–706. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viall CA, Chen Q, Stone PR, Chamley LW. Human extravillous trophoblasts bind but do not internalize antiphospholipid antibodies. Placenta. 2016;42:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albert CR, Schlesinger WJ, Viall CA, Mulla MJ, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Abrahams VM. Effect of hydroxychloroquine on antiphospholipid antibody-induced changes in first trimester trophoblast function. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71:154–164. doi: 10.1111/aji.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quenby S, Mountfield S, Cartwright JE, Whitley GS, Chamley L, Vince G. Antiphospholipid antibodies prevent extravillous trophoblast differentiation. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.07.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulla MJ, Salmon JE, Chamley LW, Brosens JJ, Boeras CM, Kavathas PB, Abrahams VM. A Role for Uric Acid and the Nalp3 Inflammasome in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Induced IL-1beta Production by Human First Trimester Trophoblast. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll TY, Mulla MJ, Han CS, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Giles I, Pericleous C, Rahman A, Sfakianaki AK, Paidas MJ, Abrahams VM. Modulation of trophoblast angiogenic factor secretion by antiphospholipid antibodies is not reversed by heparin. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;66:286–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2011.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mhatre MV, Potter JA, Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Abrahams VM. Thrombin Augments LPS-Induced Human Endometrial Endothelial Cell Inflammation via PAR1 Activation. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;76:29–37. doi: 10.1111/aji.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karumanchi SA, Stillman IE. In vivo rat model of preeclampsia. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:393–399. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmad S, Ahmed A. Elevated placental soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 inhibits angiogenesis in preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2004;95:884–891. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147365.86159.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer KR, Kaitu’u-Lino TJ, Hastie R, Hannan NJ, Ye L, Binder N, Cannon P, Tuohey L, Johns TG, Shub A, Tong S. Placental-Specific sFLT-1 e15a Protein Is Increased in Preeclampsia, Antagonizes Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling, and Has Antiangiogenic Activity. Hypertension. 2015;66:1251–1259. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Red-Horse K, Zhou Y, Genbacev O, Prakobphol A, Foulk R, McMaster M, Fisher SJ. Trophoblast differentiation during embryo implantation and formation of the maternal-fetal interface. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:744–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI22991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shtivelband MI, Juneja HS, Lee S, Wu KK. Aspirin and salicylate inhibit colon cancer medium- and VEGF-induced endothelial tube formation: correlation with suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:2225–2233. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khaidakov M, Mitra S, Mehta JL. Adherence junction proteins in angiogenesis: modulation by aspirin and salicylic acid. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2012;13:187–193. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32834eecdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad S, Hewett PW, Al-Ani B, Sissaoui S, Fujisawa T, Cudmore MJ, Ahmed A. Autocrine activity of soluble Flt-1 controls endothelial cell function and angiogenesis. Vasc Cell. 2011;3:15. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furmento VA, Marino J, Blank VC, Cayrol MF, Cremaschi GA, Aguilar RC, Roguin LP. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) upregulates beta1 integrin and increases migration of human trophoblast Swan 71 cells via PI3K and MAPK activation. Exp Cell Res. 2016;342:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Aldo PB, Barash A, Or Y, Schechtman E, Mor G, Dekel N. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2030–2036. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ning F, Liu H, Lash GE. The Role of Decidual Macrophages During Normal and Pathological Pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;75:298–309. doi: 10.1111/aji.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ratsep MT, Felker AM, Kay VR, Tolusso L, Hofmann AP, Croy BA. Uterine natural killer cells: supervisors of vasculature construction in early decidua basalis. Reproduction. 2015;149:R91–102. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faas MM, de Vos P. Uterine NK cells and macrophages in pregnancy. Placenta. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulla MJ, Myrtolli K, Brosens JJ, Chamley LW, Kwak-Kim JY, Paidas MJ, Abrahams VM. Antiphospholipid antibodies limit trophoblast migration by reducing IL-6 production and STAT3 activity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvarez AM, Mulla MJ, Chamley LW, Cadavid AP, Abrahams VM. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin prevents antiphospholipid antibody effects on human trophoblast migration and endothelial cell interactions. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:488–497. doi: 10.1002/art.38934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choudhury RH, Dunk CE, Lye SJ, Aplin JD, Harris LK, Jones RL. Extravillous Trophoblast and Endothelial Cell Crosstalk Mediates Leukocyte Infiltration to the Early Remodeling Decidual Spiral Arteriole Wall. J Immunol. 2017;198:4115–4128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierangeli SS, Vega-Ostertag ME, Raschi E, Liu X, Romay-Penabad Z, De Micheli V, Galli M, Moia M, Tincani A, Borghi MO, Nguyen-Oghalai T, Meroni PL. Toll like Receptor 4 is involved in antiphospholipid-mediated thrombosis: In vivo studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laplante P, Fuentes R, Salem D, Subang R, Gillis MA, Hachem A, Farhat N, Qureshi ST, Fletcher CA, Roubey RA, Merhi Y, Thorin E, Levine JS, Mackman N, Rauch J. Antiphospholipid antibody-mediated effects in an arterial model of thrombosis are dependent on Toll-like receptor 4. Lupus. 2016;25:162–176. doi: 10.1177/0961203315603146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colasanti T, Alessandri C, Capozzi A, Sorice M, Delunardo F, Longo A, Pierdominici M, Conti F, Truglia S, Siracusano A, Valesini G, Ortona E, Margutti P. Autoantibodies specific to a peptide of beta2-glycoprotein I cross-react with TLR4, inducing a proinflammatory phenotype in endothelial cells and monocytes. Blood. 2012;120:3360–3370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-378851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Satta N, Kruithof EK, Fickentscher C, Dunoyer-Geindre S, Boehlen F, Reber G, Burger D, de Moerloose P. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates the activation of human monocytes and endothelial cells by antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood. 2011;117:5523–5531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramesh S, Morrell CN, Tarango C, Thomas GD, Yuhanna IS, Girardi G, Herz J, Urbanus RT, de Groot PG, Thorpe PE, Salmon JE, Shaul PW, Mineo C. Antiphospholipid antibodies promote leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion and thrombosis in mice by antagonizing eNOS via beta2GPI and apoER2. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:120–131. doi: 10.1172/JCI39828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffman MK, Goudar SS, Kodkany BS, Goco N, Koso-Thomas M, Miodovnik M, McClure EM, Wallace DD, Hemingway-Foday JJ, Tshefu A, Lokangaka A, Bose CL, Chomba E, Mwenechanya M, Carlo WA, Garces A, Krebs NF, Hambidge KM, Saleem S, Goldenberg RL, Patel A, Hibberd PL, Esamai F, Liechty EA, Silver R, Derman RJ. A description of the methods of the aspirin supplementation for pregnancy indicated risk reduction in nulliparas (ASPIRIN) study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:135. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mutlu I, Mutlu MF, Biri A, Bulut B, Erdem M, Erdem A. Effects of anticoagulant therapy on pregnancy outcomes in patients with thrombophilia and previous poor obstetric history. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26:267–273. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roberge S, Demers S, Nicolaides KH, Bureau M, Cote S, Bujold E. Prevention of pre-eclampsia by low-molecular-weight heparin in addition to aspirin: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:548–553. doi: 10.1002/uog.15789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sela S, Natanson-Yaron S, Zcharia E, Vlodavsky I, Yagel S, Keshet E. Local retention versus systemic release of soluble VEGF receptor-1 are mediated by heparin-binding and regulated by heparanase. Circ Res. 2011;108:1063–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.239665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Searle J, Mockel M, Gwosc S, Datwyler SA, Qadri F, Albert GI, Holert F, Isbruch A, Klug L, Muller DN, Dechend R, Muller R, Vollert JO, Slagman A, Mueller C, Herse F. Heparin strongly induces soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 release in vivo and in vitro–brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2972–2974. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moncada S, Vane JR. Unstable metabolites of arachidonic acid and their role in haemostasis and thrombosis. Br Med Bull. 1978;34:129–135. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romano M. Lipoxin and aspirin-triggered lipoxins. ScientificWorldJournal. 2010;10:1048–1064. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]