Abstract

Background

Primary care physicians (PCPs) play a critical role in the care cascade for patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

Aim

To assess PCP knowledge and perspectives on CHC screening, diagnosis, referral, and treatment.

Methods

An anonymous survey was distributed to PCPs who participated in routine outpatient care at our hospital.

Results

Eighty (36 %) eligible PCPs completed the survey. More than half were females (60 %) aged 36–50 (55 %) from family (44 %) or internal (49 %) medicine. Overall, PCPs correctly identified high-risk populations for screening, though 19 % failed to identify baby boomers and 45 % failed to identify hemodialysis patients as populations to screen. Approximately half reported they were able to screen at risk patients<50 % of the time secondary to time constraints and difficulty assessing if patients had already been screened. 71 % of PCPs reported they refer all newly diagnosed patients to specialty care. 70 % of PCPs did not feel up to date with current treatment. The majority grossly underestimated efficacy, tolerability and ease of administration, and overestimated treatment duration. Only 9 % felt comfortable treating CHC, even those without cirrhosis. Practice patterns were influenced by specialty and Veterans Affairs Hospital affiliation.

Conclusions

Although the majority of PCPs are up to date with CHC screening recommendations, few are able to routinely screen in practice. Most PCPs are not up to date with treatment and do not feel comfortable treating CHC. Interventions to overcome screening barriers and expand treatment into primary care settings are needed to maximize access to and use of curative therapies.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, General practice, Screening, Guidelines

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a significant public health problem affecting up to 2.7 million people in the USA, although this estimate does not include incarcerated or homeless populations who have higher prevalence of CHC than the general population [1]. CHC remains the leading cause of liver transplantation and is estimated to be the cause of approximately 15,000 deaths a year [2, 3]. These adverse outcomes are anticipated to increase over the next 10–20 years given the high prevalence of CHC in the aging baby boomer population, and in the setting of increasing rates of obesity and concomitant fatty liver disease [4]. Improving screening and diagnosis of CHC has been highlighted as one of the critical interventions to improve outcomes, with both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) providing updated recommendations for one time universal hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening of baby boomers (persons born between 1945 and 1965) in 2012 and 2013, respectively [5, 6].

Despite these evidence-based recommendations and public health initiatives, implementation remains variable with some investigators reporting screening rates from 6 to <20 % among baby boomers [7, 8]. In addition to low screening rates, there are multiple other steps within the “HCV care cascade” where deficiencies preclude our ability to improve outcomes for patients with CHC. These include failure to confirm diagnosis, limited access to care, and low rates of initiation of curative treatment [9]. Whereas the low rates of referral to care and initiation of HCV therapy previously had less of an impact on overall outcomes given the poor tolerance and low rates of success among patients who underwent therapy with interferon-based regimens, this care gap has taken on exponential significance in the face of new treatment options. Currently available combinations of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) can result in sustained virologic response (SVR) in >90 % of patients with 8–24 weeks of oral therapy, and they are much less complex for providers to administer and patients to tolerate [10–13].

Given that primary care physicians (PCPs) play a critical role in the care cascade for patients with CHC, the aim of this study was to assess PCP knowledge and perspectives on HCV screening, diagnosis, referral, and treatment in the era of highly effective DAAs. We hypothesize that physician characteristics, knowledge, and prior experience influence practice patterns and that there are identifiable barriers to improving care that are amenable to interventions. Furthermore, we aim to determine whether PCPs feel comfortable treating CHC independently given that treatment has been greatly simplified and one proposed intervention to improve access to care has been the administration of HCV treatment by PCPs [14].

Methods

Survey Design

An anonymous survey was developed to assess PCPs’ perspectives on: (1) HCV screening, (2) HCV diagnosis, (3) Referral of patients to subspecialty care, and (4) HCV treatment in the current era of highly effective oral antiviral therapy. In addition, we gathered information on physician characteristics to evaluate the impact of these factors on their response. The survey was modeled based on several previously published studies evaluating PCP perspectives on HCV management [15, 16]. Domains of interest and topic questions were then edited or newly constructed based on the relevant current nuances of HCV treatment.

The survey contained 11 questions on physician characteristics, nine questions on screening and diagnosis, and 11 questions on referral and treatment. Physician characteristics of interest included demographics (age and gender), medical specialty (internal medicine, medicine/pediatrics, or family medicine), years in practice, average time allocated for new patient and return patient visits, insurance type for the majority of their patients, and number of new diagnoses of HCV they have made in the past year. The domain of questions on HCV screening and diagnosis evaluated which risk factors would prompt physicians to screen for HCV, and which diagnostic tests are used for HCV screening and confirmation of diagnosis. In addition, physicians were asked what percentage of clinic visits they felt they were able to screen for HCV based on current guidelines, potential barriers to screening, and potential interventions that may facilitate screening. The domain on HCV referral and treatment assessed how often PCPs refer a patient with CHC to subspecialty care, any delays in accessing specialty care, as well as reasons to refer or not refer. In order to characterize physicians’ self-assessment of their knowledge regarding the current treatments for HCV, respondents were asked to self-report if they felt up to date (by responding yes or no) with current HCV treatment. This was then compared to discrete knowledge assessment questions regarding current treatment regimens (including SVR rates, mode of administration, duration of therapy and tolerability). Lastly physicians were asked about their comfort level in treating CHC in their clinics. The survey was pilot tested on five internal medicine physicians. Based on their feedback, the survey was revised. The survey was designed to be completed in 5–10 min. A copy of the final survey can be obtained from the authors (M.T.). Approval to conduct this survey study was provided by our institutional review board.

Survey Administration and Recruitment

This study was conducted at the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) and the associated Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital (AAVA). UMHS is a tertiary academic medical center. For the purpose of this study, residents in training and mid-level providers (n = 15 total in primary care) were excluded. The provider list was compiled from a list of faculty who work at internal medicine (n = 118, including geriatrics), family medicine (n = 94) and medicine–pediatrics (n = 13) clinics within the two health systems. Faculty members who participated in routine outpatient care of adult patients but not those who only functioned in an administrative, research, or educational capacity were eligible for the study.

The survey was built using our institutional version of Qualtrics, an online survey design and administration tool. A recruitment email was sent to our list of PCPs explaining the aim of the study, the anonymous nature of participation, and a link to our survey. As an incentive for participation, providers were eligible to enter a raffle for a $100 VISA gift card upon completion of the survey. The first recruitment email was sent in May 2015 by the senior author. Providers received two additional follow-up recruitment email reminders from the primary author 1 and 2 weeks later. In addition, paper versions of the survey were also distributed in PCP clinic mailboxes. Respondents were asked to complete only email or paper survey but not both. Physicians were able to complete the survey over a 3-month period, starting May 2015.

Statistical Analysis

Reponses were analyzed using descriptive statistics generated by the Qualtrics software. Means and standard deviations or medians and ranges were calculated for continuous data and frequencies and percent for categorical data. Bivariate analysis to assess the impact of physician characteristics on responses was performed using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact testing using STATA. Multivariate analysis was not performed given the small sample size. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Physician Respondent Characteristics

A total of 225 physicians were eligible to participate in the study. Of these, 80 (36 %) completed the survey. Seventy providers filled out the survey online, while ten completed the paper version. Eleven additional physicians completed <90 % of the survey, and their responses were not included in the analysis. The physician and practice characteristics of all respondents, physicians who self-identified as being up to date with current HCV treatment and physicians who are primarily based at the VA are summarized in Table 1. Response rates were 33 % for internal medicine physicians, 37 % for family medicine physicians, and 46 % for medicine–pediatrics physicians.

Table 1.

Physician and practice characteristics

| All respondents (n = 80) | Self-identified up-to-date subgroup (n = 24) | VA subgroup (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 48 (60 %) | 15 (63 %) | 5 (38 %) |

| Male | 32 (40 %) | 9 (38 %) | 8 (62 %) |

| Age | |||

| 25–35 | 12 (15 %) | 2 (8 %) | 3 (23 %) |

| 36–50 | 44 (55 %) | 18 (75 %) | 7 (54 %) |

| 51–65 | 22 (28 %) | 4 (17 %) | 3 (23 %) |

| >65 | 2 (3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Specialty | |||

| Internal medicine | 39 (49 %) | 16 (67 %) | 12 (92 %) |

| Family medicine | 35 (44 %) | 6 (25 %) | 1 (8 %) |

| Medicine/pediatrics | 6 (8 %) | 2 (8 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Years in practice | |||

| <5 years | 16 (20 %) | 3 (13 %) | 3 (23 %) |

| 5–10 years | 13 (16 %) | 4 (17 %) | 4 (31 %) |

| 11–15 years | 14 (18 %) | 6 (25 %) | 1 (8 %) |

| 16–20 years | 18 (23 %) | 7 (29 %) | 2 (15 %) |

| >20 years | 19 (24 %) | 4 (17 %) | 3 (23 %) |

| Practice characteristics | |||

| Primary VA affiliation | |||

| No | 66 (84 %) | 17 (74 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Yes | 13 (16 %) | 6 (26 %) | 13 (100 %) |

| New patient appointment duration | |||

| 15–30 min | 32 (40 %) | 8 (33 %) | 1 (8 %) |

| 31–45 min | 20 (38 %) | 10 (42 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| 46–60 min | 18 (23 %) | 6 (25 %) | 12 (92 %) |

| Return visit appointment duration | |||

| <15 min | 2 (3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| 15–30 min | 75 (94 %) | 23 (96 %) | 12 (92 %) |

| 31–45 min | 3 (4 %) | 1 (4 %) | 1 (8 %) |

| Insurance of majority of patients | |||

| Mixed | 40 (50 %) | 8 (33 %) | 2 (15 %) |

| Private | 20 (25 %) | 9 (38 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Veterans Affairs | 11 (14 %) | 6 (25 %) | 11 (85 %) |

| Medicare | 5 (6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Medicaid | 4 (5 %) | 1 (4 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| No. of new HCV diagnoses in past year | |||

| Zero | 38 (48 %) | 10 (42 %) | 3 (23 %) |

| 1–5 | 39 (49 %) | 13 (54 %) | 9 (69 %) |

| 6–10 | 3 (4 %) | 1 (4 %) | 1 (8 %) |

Roughly half of the respondents were females (60 %) aged 36–50 (55 %) with an equal split from internal (49 %) or family (44 %) medicine departments. Thirteen were primarily based at the AAVA Hospital. The respondents had an equal distribution across different lengths of years in practice.

HCV Screening and Diagnosis

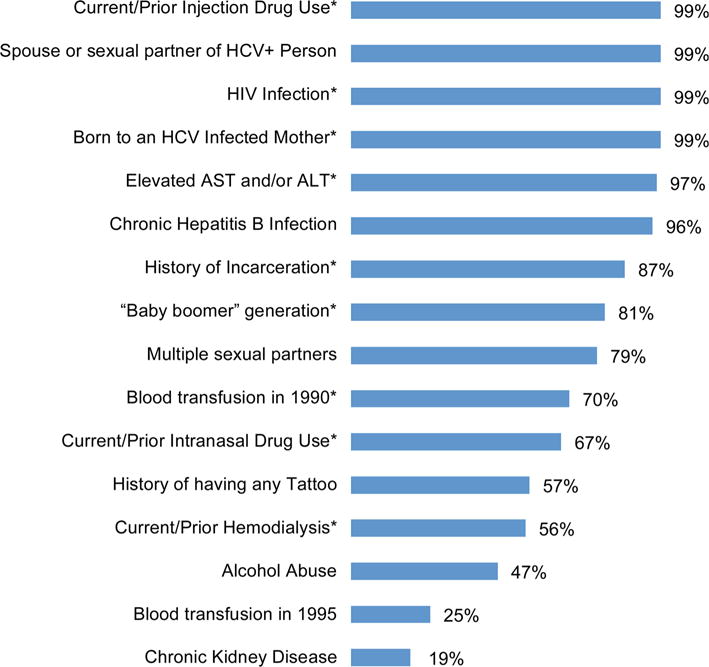

Respondents were given a list of patient characteristics and asked if they would screen for HCV based on each risk factor (Fig. 1). Overall, PCPs correctly identified high-risk populations for screening, though 19 % failed to identify baby boomers and 45 % failed to identify hemodialysis patients as higher risk populations to screen. Surprisingly, 31 % would not screen patients with a blood transfusion in 1990. Regarding knowledge of appropriate serologic testing to screen for HCV, 96 % of PCPs correctly identified the HCV antibody test. The vast majority of physicians (91 %) also identified the need for confirmatory testing with PCR assay for HCV RNA.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of primary care physicians who would screen for HCV based on patient characteristics. Characteristics with an asterisk represent USPSTF and/or CDC HCV screening recommendations

The characteristics of the PCP HCV screening practice patterns are shown in Table 2. About half of the PCPs reported that they were able to screen at risk patients <50 % of the time, and only 9 % reported they were always able to screen when indicated. One-third of physicians reported that there were clear barriers in their practice that made screening difficult, the primary reasons were time constraints (96 %) and difficulty assessing if patients had already been screened (71 %). Of note, the vast majority of respondents felt that there were discrete interventions that could be implemented to improve screening rates. All but three reported that an electronic medical record (EMR) prompt would improve screening. A third of physicians reported that there were specific instances where they elected not to screen a patient despite risk factors, mainly due to lack of time (56 %) and assuming that the patient was not a candidate for treatment (37 %).

Table 2.

Primary care physician HCV screening and referral patterns

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| HCV screening (n = 80) | |

| % clinic visits PCP able to screen at risk patients | |

| Never | 1 (1 %) |

| <25 % | 30 (38 %) |

| 25–50 % | 12 (15 %) |

| 51–75 % | 15 (19 %) |

| >75 % | 15 (19 %) |

| Always | 7 (9 %) |

| Report barriers to screening | 28 (35 %) |

| Barriers identified (n = 28) | |

| Time constraints | 27 (96 %) |

| Difficulty assessing if screened prior | 20 (71 %) |

| Lack of resources/logistical support | 16 (57 %) |

| Remaining current with guidelines | 10 (36 %) |

| Concern about insurance coverage | 9 (32 %) |

| Interventions that may improve screening (n = 80) | |

| EMR-based prompt | 77 (96 %) |

| Support staff order screening test at check in | 59 (74 %) |

| Additional patient education | 57 (71 %) |

| Opt out screening in EMR | 41 (52 %) |

| Report instances elect not to screen | 27 (34 %) |

| Reasons not to screen (n = 27) | |

| Lack of time | 15 (56 %) |

| Do not think patient will be treatment candidate | 10 (37 %) |

| Reasons for referral (n = 80) | |

| Advanced disease (i.e., cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease) | 80 (100 %) |

| Patient request | 79 (99 %) |

| Determine if therapy indicated | 79 (99 %) |

| Transplant consideration | 72 (90 %) |

| Reasons would not refer (n = 80) | |

| Medical comorbidities | 18 (24 %) |

| Psycho-social comorbidities/compliance | 16 (20 %) |

| Lack of insurance | 15 (19 %) |

HCV Referral and Treatment

The majority (71 %) of PCPs reported they refer all newly diagnosed CHC patients to subspecialty care. The main indications for referral included patients with advanced disease (100 %) and determining candidacy for treatment (99 %). The primary reason for not referring patients was medical comorbidities (24 %) (Table 2).

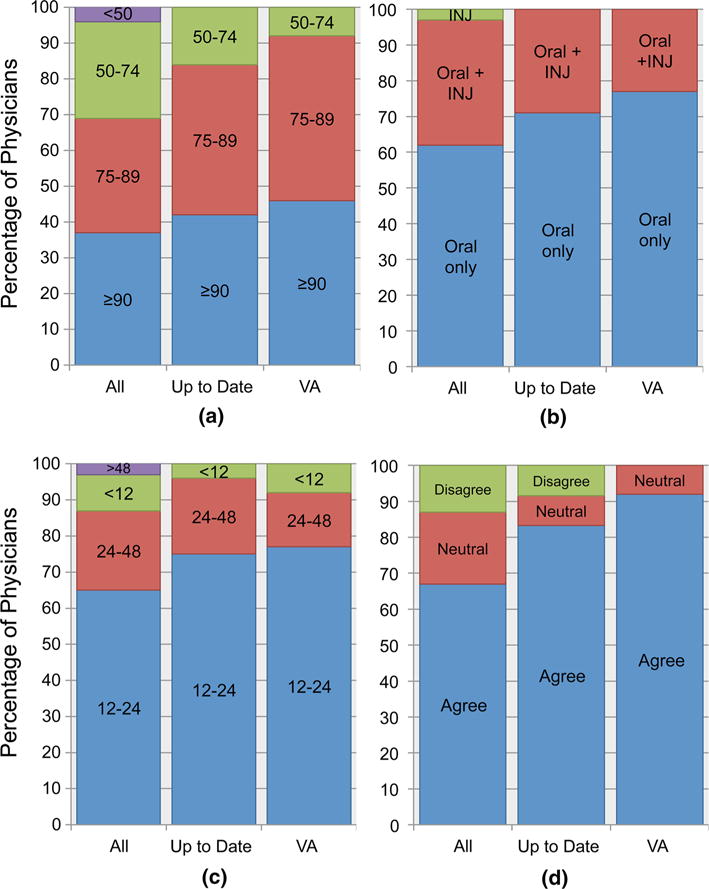

In terms of PCP knowledge about treatment for CHC, 70 % self-reported that they did not feel up to date with current HCV treatment. This personal assessment was substantiated by their responses regarding current HCV treatment (Fig. 2). The majority of physicians grossly underestimated efficacy of the latest treatment regimens with only 36 % indicating SVR rates as being ≥90 % and a third reporting SVR rates <75 %. Similarly, a large proportion of physicians underestimated the ease of administration of current therapies with 38 % failing to identify that therapy is all oral, and a fourth of physicians estimating that >24 weeks of therapy were required for the majority of patients. While 68 % of physicians agreed that current treatments are well tolerated with minimal side effects, 14 % disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement.

Fig. 2.

Primary care physician perspectives on current HCV treatment: comparison of all physicians, up-to-date physicians, and VA physicians. INJ injection. a SVR rate (%), b mode of administration, c treatment duration (weeks), d minimal side effects

When specifically analyzing physicians who self-identified as being up to date with current HCV treatment (n = 24), less than half (42 %) correctly reported SVR rates ≥90 %. A quarter were also incorrect in terms of mode of administration (29 %) and duration of therapy (25 %) (Fig. 2). Notably, PCPs that were primarily based at the VA Hospital were the most accurate when it came to HCV treatment knowledge.

When asked about treating CHC patients with the new therapies, only 9 % of PCPs reported that they were comfortable treating patients without cirrhosis and an even lower percent (5 %) feel comfortable treating patients with cirrhosis in their own clinics. Notably, of the providers that self-identified as being up to date with current HCV treatment, only 13 % stated they feel comfortable treating patients without cirrhosis in their clinic and 8 % feel comfortable treating patients with cirrhosis.

Subgroups Analysis of VA Physicians

The physicians who worked primarily at the VA Hospital (n = 13) were more often male (62 vs. 36 %), trained in internal medicine (92 vs. 41 %), and in practice for a shorter duration (54 vs. 32 % had been in practice for ≤10 years) compared to other physicians (Table 1). VA physicians were more likely to have made a new diagnosis of HCV the past year (77 vs. 48 %) than non-VA physicians. For all risk groups, the likelihood of VA physicians screening for HCV was similar or higher than non-VA physicians. A higher percent of VA physicians felt they were up to date about current HCV treatment (46 vs. 26 %); nonetheless, only 15 % of VA physicians stated they feel comfortable treating CHC patients without cirrhosis in their clinic and only 8 % feel comfortable treating CHC patients with cirrhosis.

Associations of Physician Characteristics with Responses

Potential associations between physician characteristics, practice patterns, and treatment knowledge were examined using bivariate analysis (Table 3). Compared to physicians from internal medicine, medicine–pediatrics and family medicine physicians were significantly more likely to refer all patients newly diagnosed with CHC to subspecialty care. VA physicians reported they were able to screen for HCV the majority of the time, and they referred patients to subspecialty care less frequently than non-VA physicians.

Table 3.

Bivariate associations of physician characteristics and responsea

| Physician characteristic | Screen baby boomers | Able to screen in >75 % clinic visits | Refer all HCV patients | SVR with current treatment ≥90 % | Comfortable treating patients without cirrhosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | |||||

| Internal medicine | 72 | 33 | 67 | 46 | 15 |

| Med/peds | 83 | 50 | 100 | 17 | 0 |

| Family medicine | 91 | 17 | 94 P = 0.01 |

29 | 3 |

| Years in practice | |||||

| <10 | 86 | 38 | 92 | 34 | 7 |

| 11–20 | 84 | 22 | 80 | 31 | 13 |

| >20 | 68 | 21 | 67 | 47 | 5 |

| VA Affiliation | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 62 | 42 | 46 | 15 |

| No | 82 | 21 P = 0.006 |

89 P = 0.001 |

35 | 8 |

| Cases of HCV diagnosed in last year | |||||

| 0 | 76 | 29 | 86 | 42 | 8 |

| 6–10 | 86 | 26 | 78 | 31 | 10 |

Values in table are percentages

Discussion

Chronic hepatitis C remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality [2, 4]. Fortunately, there have been dramatic advances in CHC treatment with cure now attainable for >90 % patients using simple regimens with minimal side effects and of short duration [10–13]. However, only a small percent of patients benefit from these treatment advances. Many steps need to be accomplished to decrease the burden of CHC at an individual and public health level [17]. PCPs play a critical role in the initial steps in the care cascade for patients with CHC, specifically as it relates to their role in screening, diagnosis, and referral to care. In this era of highly effective and simple treatment regimens for CHC, PCPs also have the potential to broaden access to treatment should they feel comfortable treating in the primary care setting. Given this significant potential impact PCPs can have on improving outcomes for patients with CHC, we conducted this survey to assess PCP knowledge and perspectives on HCV screening, diagnosis, referral, and treatment.

Our survey results demonstrated that PCPs were generally up to date with screening recommendations for CHC, though there remains room for improvement. Specifically, 19 % of PCPs failed to identify baby boomers as a higher risk population despite CDC and USPSTF recommendations [5, 6]. Additionally, 45 % of PCPs failed to identify hemodialysis patients as populations to screen. Compounding these gaps in identifying at risk populations is the reported low rates of PCPs being able to routinely screen patients in clinical practice due to time constraints and difficulty assessing if patients had been previously screened. Our survey revealed interventions that PCPs considered helpful to increase screening including implementing an EMR-based prompt and having clinic staff initiate screening using an order set. These steps have been implemented at our hospital, and preliminary results are encouraging. Other groups have tried a similar approach and found that it increased screening significantly [8].

There did not appear to be notable deficiencies in terms of diagnosis and confirmation. In terms of referral patterns, the majority of PCPs (71 %) reported they refer all newly diagnosed CHC patients to specialty care. Our findings with regard to treatment were most notable with 70 % of PCPs self-reporting they did not feel up to date with current treatment. This sentiment correlated with the answers regarding treatment characteristics with the majority grossly underestimated efficacy, tolerability and ease of administration, and overestimated treatment duration. Even among those PCPs who did report feeling up to date, the accuracy of their responses was poor. Relatedly, only 9 % feel comfortable treating CHC patients without cirrhosis in their own clinics. Given the high prevalence of CHC and greatly simplified treatment regimens, many have advocated for PCPs to treat non-cirrhotic patients [14]. Our results showed that PCPs, even in tertiary care settings, do not feel comfortable initiating therapy. This is not a complete surprise, as this transition would require an extension of care outside their general scope of practice, and even up-to-date physicians had difficulties keeping up with the basic tenets of the rapidly evolving treatment options. One proposal that is likely more tenable is the identification and training of “PCP HCV Champions” who will incorporate CHC treatment into their practice. Identifying and training these physicians has been shown to produce similar rates of success even with more complicated interferon-based treatment [18].

Some responses were impacted by physician characteristics. Physicians with medicine–pediatrics and family medicine training were more likely to refer all newly diagnosed CHC patients to specialty care as compared to their internal medicine colleagues. This is not unexpected given the broad scope of practice of these providers as compared to providers focused on adult medicine alone. VA physicians reported they are able to screen for HCV more often, refer newly diagnosed CHC patients less, and had more accurate responses to questions pertaining to treatment. These differences may reflect fundamental differences in patient populations seen in VA hospitals as well as established infrastructure within the VA to diagnose and care for CHC. The major strength of our study is the sampling of physicians from all fields of primary care. This study also represents updated views of PCPs in an era of rapidly evolving treatment of CHC. There are several limitations to our study. It was conducted at a single academic medical center and may not reflect primary care practices in community settings. Our response rate was low but in line with rates for other surveys using a similar methodology or on the same topic [16, 19]. Lastly, our study was brief, and we may have missed important information that is relevant to this topic, and responses to our survey may not fully match with actual practice.

In summary, PCPs are generally up to date with HCV screening recommendations and appropriate diagnostic testing, but there remain areas for improvement, specifically as it relates to screening of baby boomers. In addition, PCPs are referring most CHC patients to subspecialty care and presently do not feel comfortable treating these patients in their practice. Several distinct interventions were identified that could decrease care gaps for patients with CHC, namely the incorporation of a prompt in the EMRs for HCV screening as well as the identification and training of “PCP HCV Champions” who could extend treatment into the primary care setting. Application of these interventions into our current care model will allow more patients to benefit from curative treatments and accelerate the decline in HCV disease burden.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the Tuktawa Foundation (Lok).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest: A.S.F.L. has received research grants from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Idenix, and Merck; and has served as unpaid advisor for Gilead, and paid advisor for Merck. All the other authors have no relevant person interests to declare.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standard of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Our institutional review board determined that our study did not require informed consent from the anonymous survey participants.

References

- 1.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300. doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, et al. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;165:271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman RB, Steffick DE, Guidinger MK, et al. Liver and intestine transplantation in the United States, 1997–2006. Am J Transpl. 2008;8:958–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McHutchison JG, Bacon BR. Chronic hepatitis C: an age wave of disease burden. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S286–S295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyer VA. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:349–357. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;16:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adebajo CO, Aronsohn A, Te HS, et al. Abstract no. 1066, Digestive Disease Week. Washington, DC: May 16–19, 2015. Birth cohort HCV screening is lower in the Emergency Department than the outpatient setting [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litwin AH, Smith BD, Drainoni M, et al. Primary care-based interventions are associated with increases in hepatitis C virus testing for patients at risk. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:497–503. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmberg SD, Spradling PR, Moorman AC, Denniston MM. Hepatitis C in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859–1861. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1302973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Afdhal N, Zuesem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J, et al. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1983–1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1594–1603. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghany MGND, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433–1444. doi: 10.1002/hep.24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asrani SK, Davis GL. Impact of birth cohort screening for hepatitis C. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;16:381–387. doi: 10.1007/s11894-014-0381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark EC, Yawn BP, Galliher JM, Temte JL, Hickner J. Hepatitis C identification and management by family physicians. Fam Med. 2005;37:644–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shehab TM, Sonnad SS, Lok ASF. Management of hepatitis C patients by primary care physicians in the USA: results of a national survey. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:377–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umsccheid CA, Lo Re V. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2199–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;9:32. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]