Abstract

Purpose

To describe a case of a patient with BRAF mutation-positive cutaneous melanoma who developed acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy (AEPVM) during vemurafenib and pembrolizumab treatment for metastatic melanoma.

Methods

Retrospective case report documented with wide-field fundus imaging, spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and fundus autofluorescence imaging.

Results

A 55-year-old woman bilateral ductal breast carcinoma and BRAF mutation positive metastatic cutaneous melanoma complained of bilateral blurred vision within five days of starting vemurafenib (BRAF inhibitor). She had been on pembrolizumab (program death receptor antibody) and intermittently on dabrafenib (BRAF inhibitor) and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) and had a normal ophthalmologic exam. On presentation three weeks after the introduction of vemurafenib her visual acuity (VA) had declined to 20/40, both eyes. Her exam showed diffuse elevation of the fovea with multifocal yellow-white, crescent-shaped subretinal deposits within the macula of both eyes and bilateral neurosensory retinal detachments by SD-OCT. Discontinuation of vemurafenib and introduction of difluprednate and dorzolamide led to a gradual resolution (over four months) of the neurosensory detachments with recovery of vision.

Conclusion

This case report suggests AEPVM may be directly associated with the use of BRAF inhibitors as treatment for metastatic cutaneous melanoma, or indirectly by triggering autoimmune-paraneoplastic processes. Future identification of similar associations is required to unequivocally link vemurafenib and/or pembrolizumab to AEPVM in metastatic melanoma.

Keywords: acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy, MEK inhibitor, BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib, pembrolizumab, central serous retinopathy, paraneoplastic retinopathy, metastatic melanoma

Introduction

Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy (AEPVM) describes an infrequent retinal disorder characterized by multifocal round or crescent-shaped yellow subretinal deposits with a vitelliform appearance that correspond to multifocal serous retinal detachment on optical coherence tomography (OCT).1 Associated symptoms include blurred vision, metamorphopsia, nyctalopia, and photopsia. AEPVM has been described as a feature of a paraneoplastic syndrome in association with cutaneous or choroidal melanoma, carcinoma, and immunogammopathies, as well as in association with trauma, infectious disease such as viral illnesses (e.g., hepatitis C, Coxsackie B, HIV), syphilis and Lyme disease, or as an idiopathic process.2,3 Although the mechanism of disease is not fully understood, there is increasing evidence in support of an autoimmune process involving retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptor proteins.2,3

Personalized cancer therapy that targets pathways disrupted by specific gene mutations is one of the recent triumphs of medicine and has significantly extended the survival of patients with metastatic cutaneous melanoma.4 One such target is B-raf, a serine-threonine protein kinase involved in signal transduction encoded by the BRAF oncogene. B-raf is immediately upstream of and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK). MEK inhibition targets MEK in the MAPK/ERK pathway resulting in apoptosis, while MEK activation encourages cell proliferation. In recent years, MEK inhibitors have been implicated in myriad ophthalmic sequelae such as neurosensory retinal detachment, vascular injury, anterior uveitis, visual field defects, and others.5,6,7 The increasing incidence of cutaneous melanoma combined with extended survival rates due to the advent of these newly targeted treatments could potentially lead to increased recognition of paraneoplastic and treatment-associated retinopathies. We report a case of AEPVM that developed during a complex treatment regimen for metastatic cutaneous melanoma that included the use of BRAF and MEK inhibition as well as immunotherapy.

Case Presentation

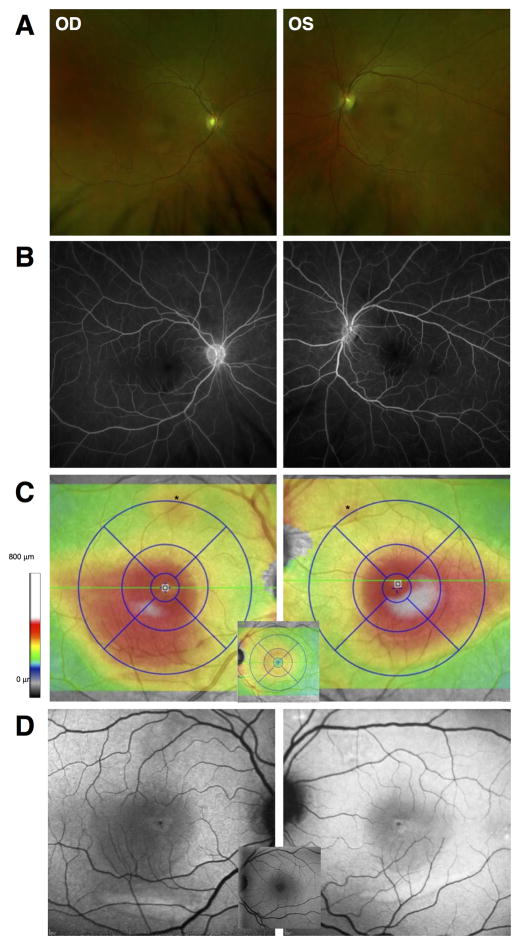

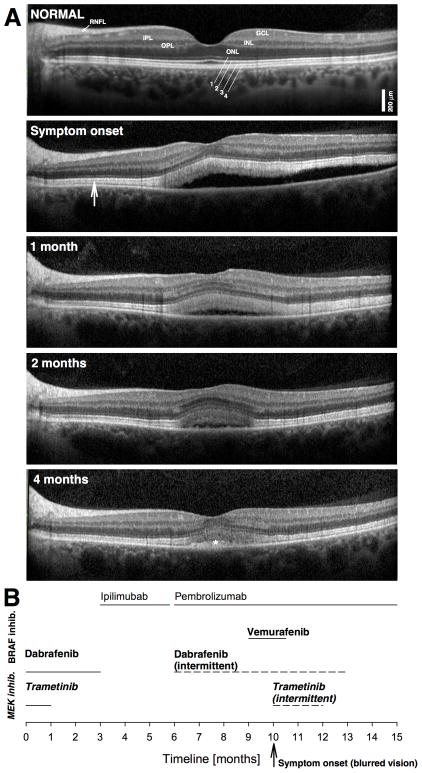

A 55-year-old woman with history of bilateral ductal breast carcinoma in situ post mastectomy (2002) as well as cutaneous melanoma with BRAF mutation positive (BRAFV600E) and metastatic disease to heart, lungs, liver, and brain, developed bilateral central blurring of vision. She had a complicated course of pharmacotherapy for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Ten months prior to ocular symptoms, she was started on dabrafenib (150 mg twice a day by mouth; a BRAF inhibitor) and trametinib (2mg/day by mouth; a MEK inhibitor). She developed fever and was started on oral prednisone (5–20 mg/day) while trametinib was discontinued. Three months later, dabrafenib was also discontinued and infusions of ipilimumab (3mg/Kg, an anti-cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte-associated protein 4 monoclonal antibody) were started. After three months, the patient was switched to pembrolizumab (2mg/Kg, a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody to programmed cell death 1 receptor) due to progressive disease and she was re-started on dabrafenib, which she took intermittently due to side effects. Three months later vemurafenib (another BRAF inhibitor) was added. Within five days she reported bilateral subjective change in vision but had an unremarkable ophthalmologic exam with 20/20 visual acuity (VA) in both eyes. However, on follow up three weeks later her VA had declined to 20/40 in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were normal, anterior segment examination was unremarkable, and there was no evidence of intraocular inflammation. There was a shallow, diffuse elevation of the fovea with multifocal yellow-white, crescent-shaped subretinal deposits within the macula of both eyes (Figure 1A). Fluorescein angiography did not show staining or leakage (Figure 1B). Spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) demonstrated overall retinal thickening involving the inferotemporal macula in both eyes (Figure 1C). Short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (FAF) showed an overall increased FAF most prominent as a crescent-shaped area in the inferior macula in both eyes, corresponding to the deposits (Figure 1D). SD-OCT cross-sections at initial evaluation showed bilateral neurosensory retinal detachment with a thick, highly reflective band sclerad to the ellipsoid zone band extending to adjacent regions without neurosensory detachment (Figure 2A).

Figure 1.

A. Wide angle fundus photography showed a shallow, diffuse elevation of the macula and multifocal yellow-white depigmented lesions in both eyes. B. Mid-phase fluorescein angiography images did not show staining, pooling, or leakage in either eye. C. SD-OCT total retinal thickness topography maps showed increased overall retinal thickening extending from the foveal center to inferotemporal central retina in both eyes. D. Short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (FAF) showed a diffuse increase in FAF that lightened the normally dark central region caused by macular pigment. Normal appearance is shown for reference as central insets in C and D.

Figure 2.

A. SD-OCT horizontal cross-sections of the left eye of the patient at presentation compared with appearance on follow up visits. Hyporeflective (dark) nuclear layers labeled on the normal subject (ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer) are delimited by highly reflective synaptic layers (IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer) and the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). Outer photoreceptor/RPE laminae are labeled (1, external limiting membrane; 2, ellipsoid zone; 3 interdigitation between photoreceptor outer segment tips and RPE; cells; 4, RPE), following conventional terminology. A widened hyperreflective band sclerad to the ellipsoid zone layer is more prominent centrally but extends to regions without obvious neurosensory detachment (vertical arrow). A normal SD-OCT cross-section is shown for comparison. B. Time line of treatments; MEK inhibitors in bold and italics letters; BRAF inhibitors in bold.

A BRAF-associated or MEK-associated retinopathy versus paraneoplastic vitelliform maculopathy was considered. Vemurafenib was discontinued but the patient was continued on pembrolizumab and dabrafenib alternating with trametinib only a few days per week due to side effects. Difluprednate four times a day and dorzolamide twice a day were initiated in both eyes. Over the next four months, there was slow resolution of bilateral foveal neurosensory detachments with improvement of VA to 20/20 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye despite continuation of BRAF- and MEK-inhibition therapy (Figure 2). At the last SD-OCT evaluation, there was normalization of the central retinal architecture with only a small foveal elevation above residual hyperreflective material (Figure 2A, asterisk) associated with general improvement of the patient’s well being. ERGs and retinal autoimmune antibody testing was considered but was not pursued given the pre-terminal status and symptomatic improvement of the patient. She died one month later (five months after presentation with ocular symptoms) from complications of melanoma-related brain metastases.

Discussion

Bilateral serous retinal detachment occurring shortly after initiation of MEK inhibition have been increasingly recognized as a drug class side effect, whereas retinal abnormalities following BRAF inhibition alone classically include features of uveitis but not typically serous retinal detachment.5,6,7 In the largest study to date, 90% of patients (46/51) treated with binimetinib (MEK inhibitor) showed subretinal fluid (SRF), which usually involved the foveal region.6 Also reported are multifocal, elevated, yellow subretinal deposits, usually near the vascular arcades, as seen in our patient, which are similar to AEPVM, a syndrome long suspected to have an inflammatory and/or immune-mediated.2,3 In the setting of a high-stakes, complex treatment regimen such as that exemplified by our patient, the question is whether the retinal changes constitute the result of drug adverse effect in the MAPK pathway through MEK and/or BRAF inhibition, an immune-related adverse event in response to the immunotherapy with pembrolizumab, or simply a paraneoplastic manifestation of cutaneous melanoma. Addressing these possibilities is beyond a mere academic exercise since adjustments of medications could be life threatening. As survival from cutaneous melanoma and other types of cancer will hopefully continue to improve with the introduction of newer and often immune-related treatments, the patient’s overall care, including VA and adverse events, may take on a more complex role with influence on treatment algorithms. Vitelliform subretinal deposits, especially in a patient with known metastatic cancer, should also trigger a concern for possible ocular metastasis.

The introduction of vemurafenib in our patient coincided with the perceived change in VA and clinically apparent central serous detachment. However, this patient had been on a similar medication, dabrafenib and trametinib (BRAF and MEK inhibition) for months without visual complaints, arguing against a pathogenic role of these medications. Studies regarding ocular side effects of vemurafenib and similar medications have identified uveitis, conjunctivitis, and dry as the major findings, mostly occurring at >90 days after treatment initiation.5 The presence of subretinal fluid has not been reported.5 Serous retinal detachment has been observed in a high proportion of patients on MEK-inhibition associated with mild subjective visual symptoms and showing prompt resolution upon MEK inhibitor cessation or can be transient with sustained use.5,6,7 It has been suggested that the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors may ameliorate the dermatological side effects of BRAF inhibition alone, although there is concern for possible added retinal side effects known to occur with MEK inhibition.4 Her vitelliform lesions did not change after discontinuation of BRAF inhibition with vemurafenib or improve when trametinib (MEK inhibitor) was stopped for two weeks and then re-instituted in the original BRAF/MEK (dabrafenib/trametinib) combination, as might have been expected if these medications were causing the retinopathy (Figure 2).

Paraneoplastic AEPVM is a variant of melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR), a paraneoplastic syndrome classically characterized by acute vision changes, an unremarkable retinal examination, electrophysiologic evidence of inner retinal dysfunction, and positive autoantibodies to retinal bipolar cells.2,3 Vitelliform retinal lesions in association with depigmented skin lesions have been documented in MAR.8 Interestingly, checkpoint inhibitors can cause or exacerbate autoimmune diseases including MAR and vitiligo.8 Favorable response to systemic immunosuppression in rare cases of ipilimumab-associated retinopathy is consistent with that possibility.9 We thus considered the possibility that pembrolizumab could have potentiated an immune-related adverse event in our patient.10 Topical corticosteroids eyedrops, as used in this case (our patient was already on systemic corticosteroids), as well as periocular or intraocular corticosteroid injections, are options to consider when vision and/or the structural integrity of the retina is threatened. Local immunosuppression avoids interference with the anti-cancer treatments aimed to boost anti-tumor immune response. Resolution of the serous detachment with recovery of vision in our patient with topical corticosteroid use occurred gradually over the course of months, unlike the rapid resolution of MEK-associated retinopathy following discontinuation of MEK inhibition, additionally supporting the belief that this patient was manifesting a paraneoplastic vitelliform retinopathy.

We speculate that these minimally symptomatic retinal changes may become in vivo histological biomarkers of treatment efficacy and potentially useful to oncologists. Future identification of similar associations is required to unequivocally link vemurafenib and/or pembrolizumab to AEPVM in metastatic melanoma.

Summary statement.

A 55-year-old woman presented with decreased vision one week after vemurafenib was added to pembrolizumab as treatment for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. She was diagnosed with presumed-paraneoplastic acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Vision and neurosensory retinal detachment improved gradually after discontinuation of vemurafenib and initiation of topical difluprednate.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gass JD, Chuang EL, Granek H. Acute exudative polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1988;86:354–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Dahmash SA, Shields CL, Bianciotto CG, et al. Acute exudative paraneoplastic polymorphous vitelliform maculopathy in five cases. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2012;43:366–73. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20120712-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronow ME, Adamus G, Abu-Asab M, et al. Paraneoplastic vitelliform retinopathy: clinicopathologic correlation and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Eng J Med. 2012;367:107–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choe CH, McArthur GA, Caro I, et al. Ocular toxicity in BRAF mutant cutaneous melanoma patients treated with vemurafenib. Am J Oph. 2014;158:831–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber ML, Liang MC, Flaherty KT, Heier JS. Subretinal fluid associated with MEK inhibitor use in the treatment of systemic cancer. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:855–862. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dijk EH, van Herpen CM, Marinkovic M, et al. Serous retinopathy associated with mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition (Binimetinib) for metastatic cutaneous and uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1907–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audemard A, de Raucourt S, Miocque S, et al. Melanoma-associated retinopathy treated with ipilimumab therapy. Dermatology. 2013;227:146–149. doi: 10.1159/000353408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong RK, Leek JK, Huang JJ. Bilateral drug(ipilimumab)-induced vitritis, choroiditis, and serous retinal detachments suggestive of Vogt-koyanagi-harada syndrome. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2012;6:423–6. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e31824f7130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts P, Fishman GA, Joshi K, Jampol LM. Chorioretinal lesions in a case of melanoma-associated retinopathy treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134:1184–1188. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]