Abstract

To inform recommendations for the exercise component of a healthy lifestyle intervention for adults with obesity and treated obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), we investigated the total energy expenditure (EE) and cardiorespiratory response to weight-supported (cycling) and unsupported (walking) exercise. Individuals with treated OSA and a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 performed an incremental cardiopulmonary exercise test on a cycle ergometer and a treadmill to determine the peak oxygen uptake . Participants subsequently completed two endurance tests on each modality, matched at 80% and 60% of the highest determined by the incremental tests, to intolerance. The cardiorespiratory response was measured and total EE was estimated from the . Sixteen participants completed all six tests: mean [SD] age 57 [13] years and median [IQ range] BMI 33.3 [30.8–35.3] kg/m2. Total EE during treadmill walking was greater than cycling at both high (158 [101] vs. 29 [15] kcal; p < 0.001) and moderate (178 [100] vs. 85 [59] kcal; p = 0.002) intensities, respectively, with similar cardiorespiratory responses and pattern of EE during rest, exercise and recovery. Contrary to current guidelines, walking might be the preferred training modality to achieve the combination of weight loss and increased cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with obesity and treated OSA.

Keywords: Energy expenditure, obstructive sleep apnoea, obesity, exercise, weight supported, weight unsupported

Introduction

Obesity is increasing in prevalence across the socio-economic spectrum, with currently over one-third of adults being overweight and over one-tenth being obese worldwide.1 Although obese individuals who maintain their fitness have a lower cardiovascular mortality than their unfit counterparts,2 the majority of obese individuals are less physically active than those of normal weight and do not achieve the recommended levels of physical activity to maintain health.3,4 The inactivity associated with obesity may be compounded in the presence of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), itself known to be associated with fatigue and inactivity, which persists even when the OSA has been effectively treated with continuous positive airway pressure therapy (CPAP).5 The presence of OSA among obese individuals is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease6,7 such that those with OSA and obesity have a higher morbidity and mortality than those with obesity alone.8,9 Therefore, there is interest in developing lifestyle interventions that target both weight loss and cardiorespiratory fitness, for adults with obesity-related OSA, with the aim of reducing long-term cardiovascular risk.10–12

Health organizations have merged recommendations on diet, physical activity and obesity13 acknowledging that a healthy lifestyle is better realized by a combination of diet and exercise than by diet alone.14–16 However, although many studies have compared different diets and their impact on weight loss17 few have investigated which exercise training modality is the most effective for individuals with obesity to achieve healthy weight loss whilst improving cardiovascular fitness.10

Weight loss attributable to exercise will be directly proportionate to the energy expenditure (EE) that is, work, whilst cardiorespiratory fitness, as measured by peak oxygen uptake , responds to exercise training in a dose-like fashion18 and a minimum intensity is required for an effective fitness program. Adults with obesity can exercise safely at moderate (60%) and vigorous (80%) intensities.19 However, increasing exercise intensity decreases the tolerable duration of exercise exponentially and can compromise the goal of negative energy balance for weight loss.20

Although the ideal modality for adults with obesity requires significant EE whilst stimulating improved fitness, the relationship between intensity, modality, exercise tolerance and total EE in this population remains unknown. In healthy individuals, it is established that achieved on an incremental cycle test to intolerance is slightly lower, 90–100%,21 to that achieved on a corresponding treadmill test. In adults with obesity, however, walking may increase the weight bearing energy demands so much it causes early fatigue and termination of the exercise. If so, the tolerability of continuous weight bearing exercise, that is, a typical training session, may be too short to induce the benefits of training. Therefore, cycling has been recommended in the initial stages of a fitness training program until weight bearing activities, such as walking, can be more easily achieved.22,23 Lafortuna et al., however, proposed that walking might be the best way to increase total EE but their data did not investigate tolerability or sustainability of exercise.24

In order to better inform recommendations for exercise, this study evaluated whether weight-supported exercise (cycling) was associated with a greater total EE at a matched aerobic intensity to intolerance compared with unsupported exercise (walking) in adults with obesity and treated OSA. We hypothesized that individuals with obesity would sustain cycling for longer than walking, resulting in their achieving greater work, due to the weight being supported with cycling.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01930513) approved by the local ethics board (JREB2010-10). After providing written informed consent, each participant completed six tests by attending four assessment visits each separated by at least 48 hours. The first two visits comprised, in random order, an incremental treadmill (ITM) and cycle (ICE) test. The third and fourth visits comprised, in random order, two constant speed tests on a treadmill and two constant power tests on a cycle ergometer. Age, gender, height and weight were documented and spirometry completed.25

Participants

Individuals with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 were recruited from a sleep clinic. All patients had OSA treated with CPAP for at least 3 months. As part of their referral for sleep apnoea patients underwent a medical evaluation. Individuals with chronic lung or heart disease diagnosed by history, examination or pulmonary function tests or other conditions that might interfere with exercise, were excluded.

Incremental exercise

The purpose of the incremental test was to determine , observe the systemic response and sensations to the tolerable range of power, as well as to establish the relationship between and power for the individual. Predicted peak power was estimated using age, height, weight and gender.26 Both protocols were designed to achieve a linear response in and achieve at 10 minutes.21 The treadmill protocol27 uses a linear increase in walking speed and a curvilinear increase in grade to produce a linear profile of power and previously demonstrated in individuals with obesity.28 Walking was performed on a treadmill (Trackmaster TMX425, Full Vision Inc., Newton, Kansas, USA). Cycling was performed on a semi-recumbent ergometer (Angio LD917904, Lode.nl, the Netherlands) to accommodate the body habitus and to prevent premature cessation of exercise due to saddle discomfort. Expired gas analysis was measured breath by breath (Oxycon Pro 808302; Erich Jaeger GmbH, Wurzburg, Germany) to determine, and . Heart rate (HR) via electrocardiography, oxygen saturation (forehead sensor, Nellcor Max Fast, Pleasanton, California, USA), blood pressure (BP) and the modified CR-10 Borg scale29 for breathlessness (BS) and leg effort (LE) were assessed before and during the test. The anaerobic threshold (AT) was estimated using the modified v-slope method supported by gas exchange and ventilatory criteria.30

Constant power exercise

The purpose of the constant power tests was to observe the tolerability of exercise and measure the EE achieved at two recommended training intensities (simulating exercise training sessions) with the different modalities. Two constant speed treadmill tests and two constant power cycle tests were performed, in separate sessions, at a matched intensity of 80 and 60% defined as the highest observed during the incremental tests. The relationship between and power was used to set the appropriate mode specific power to achieve the same cardiorespiratory intensity on the cycle and treadmill constant power tests (Figure 1). The vigorous intensity test was always first with at least a 20 minutes rest before the moderate intensity test. Participants were asked to perform the tests until exhaustion or to a limit of 40 minutes. Measurements were the same as the incremental tests including expired gas analysis, HR, oxygen saturation, BP and, BS and LE.

Figure 1.

An example of how the power was calculated for the constant power tests from the incremental treadmill (triangles) tests and cycle (circles) tests. The (solid reference line) was highest on the treadmill test; 80% and 60% were 2168 and 1626 mL minute−1, respectively. Therefore, the power for the cycle endurance tests at 80% and 60% were 134 W (circled 1) and 87 W (circled 2), respectively. The power for the endurance treadmill tests at 80% and 60% was 102 W (circled 3) and 54 W (circled 4), respectively. The respective grade and speed for treadmill exercise was derived from the original protocol. In this case it was 9% grade at 4.2 km hour−1 and 8% grade at 2.9 km hour−1. : peak oxygen uptake; : oxygen uptake.

EE for exercise and recovery phases was estimated from the measured assuming an energy equivalent for oxygen of 5 kcal (21 kJ) per 1 L of oxygen uptake.31 The total for the duration of the phase was calculated by integrating , minus the average resting , over time (the area under the curve above rest). The recovery phase was identified objectively; recovery started at the end of exercise and ended when the returned to steady-state resting level confirmed by a zero slope in the over time after the end of the recovery phase.32 The total EE was defined as the sum of the exercise and recovery EE.

Statistical analysis

The baseline demographics are presented as mean (SD) for normally distributed variables and median (interquartile [IQ] range) for variables not normally distributed. The peak parameters for the ITM and ICE were compared by paired t-tests for parametric data and Wilcoxon rank test for non-parametric data.

The EE of the constant power tests was analysed using a repeated measures analysis of variance (2 × 2) with factors of intensity (moderate and vigorous) and modality (treadmill and cycle). In the event of significant effects, post hoc comparisons were made using paired t-tests for parametric data and Wilcoxon rank test for non-parametric data.

A qualitative visual comparison of the average cardiorespiratory response was produced by smoothing individual tests into epochs of 10% increments of the test duration (i.e. deciles) using a negative exponential data transformation and then calculating the group mean at each decile.

Sample size was determined to ensure adequate statistical power to test the hypothesis of a significant effect of modality on exercise tolerance resulting in greater work. The estimated standard deviation of the difference in exercise time in repeated constant power exercise is 2.8 minutes.33 A difference of 3.4 minutes would be considered a large effect.34 We used a more conservative approach, medium effect (2.1 minutes), to ensure an adequate sample size. To reject the null hypothesis of no difference between modality using a two-tailed paired t-test (power = 0.80 and significance level = 0.05) of dependent means, we estimated that 16 participants needed to complete this study.

Results

Participants

Eighteen patients agreed to participate. One was excluded due to undiagnosed COPD and another sustained an injury at home. Sixteen participants completed all six exercise tests (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| N (Male: Female) | 8:8 |

| Age (years) | 57.0 [12.9] |

| BMI (kg m−2)a | 33.3 [30.8–35.3] |

| Waist/Hip Ratio | M 0.9 [0.05]; F 1.00 [0.04] |

| FEV1 (L) | 3.0 [0.9] |

| FEV1% predicted | 99 [13] |

| FVC (L) | 4.0 [1.2] |

| FVC % predicted | 101 [16] |

| FEV1/FVC | 77 [10] |

| Duration of CPAP (y)a | 1.0 [0.5–7.5] |

| CPAP pressure (cm H2o)a | 8.5 [7.0–11.8] |

| AHI index on CPAPa | 4.0 [0.6–6.0] |

| AHI index before treatmenta | 42.5 [30.3–66.0] |

BMI: body mass index, FEV1: forced expired volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; AHI: apnoea-hypopnoea index. aMean [SD] unless which represents Median [interquartile range].

Incremental exercise

achieved on the cycle ergometer was 78.3[10.1] % (p < 0.001) of that achieved on the treadmill (the treadmill was higher than the cycle ergometer for all participants).Comparisons of parameters at peak exercise are shown in Table 2. was lower throughout cycling compared to treadmill (Figure 2), and HR were higher, whereas the respiratory exchange ratio was not different. BS and LE were higher for cycling than for treadmill walking throughout (Figure 3) and there was a greater level of LE at the end of cycling compared with treadmill. Overall, there was no significant difference in the self-reported limiting symptom (LS) at the end of exercise between ICE and ITM (p = 0.29). LE was the LS in 13/16 participants for ICE compared to 6/16 for ITM. BS (7/16) was the commonest LS for the ITM test.

Table 2.

A comparison of the results at peak exercise between the ITM and ICE tests.a

| ITM | ICE | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration (seconds) | 621 (97) | 576 (150) | 0.30 |

| (mL minute−1) | 2301 (535) | 1814 (389) | <0.001 |

| (mL minute−1 kg1) | 23.5 (5.6) | 18.4 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| (% predicted) | 85 [19] | 68 [16] | NA |

| (mL minute−1) | 2662 (755) | 2135 (551) | <0.001 |

| RER | 1.18 (0.08) | 1.17 (0.12) | 0.69 |

| (L minute−1) | 83.3 (24.7) | 66.9 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| @ AT (mL minute−1) | 1463 (238) | 1208 (165) | <0.001 |

| AT (% predicted) | 58 (12) | 47 (13) | 0.003 |

| HR (bpm) | 144 (29) | 130 (21) | 0.01 |

| HR % predicted | 89 (14) | 80 (13) | <0.001 |

| SpO2 (%) | 98 (1) | 98 (1) | 0.18 |

| BP systolic (mmHg) | 165 (31) | 166 (33) | 0.90 |

| BP diastolic (mmHg) | 82 (13) | 75 (17) | 0.04 |

| BS | 6.6 (1.7) | 7.1 (2.2) | 0.45 |

| LE | 5.8 (2.1) | 7.5 (1.6) | 0.01 |

ITM: oncremental treadmill test; ICE: incremental cycle ergometer; HR: heart rate; SpO2: oxygen saturation; BP: blood pressure; : peak oxygen uptake; : peak carbon dioxide elimination; RER: respiratory exchange ratio; : ventilation; BS: Borg Score Breathless Scale; LE: Borg Score Leg Effort; AT: anaerobic threshold.

aMean (SD) HR predicted = 220 – age (years), NA: not applicable.

Figure 2.

A comparison of the exercise cardiorespiratory responses between incremental treadmill (triangles) and cycle (circles) ergometer tests in adults with obesity. : oxygen uptake; : ventilation, RER: respiratory exchange ratio.

Figure 3.

A comparison of the symptom responses between incremental treadmill (triangles) and cycle (circles) ergometer tests in adults with obesity.

Constant power exercise–simulated training sessions

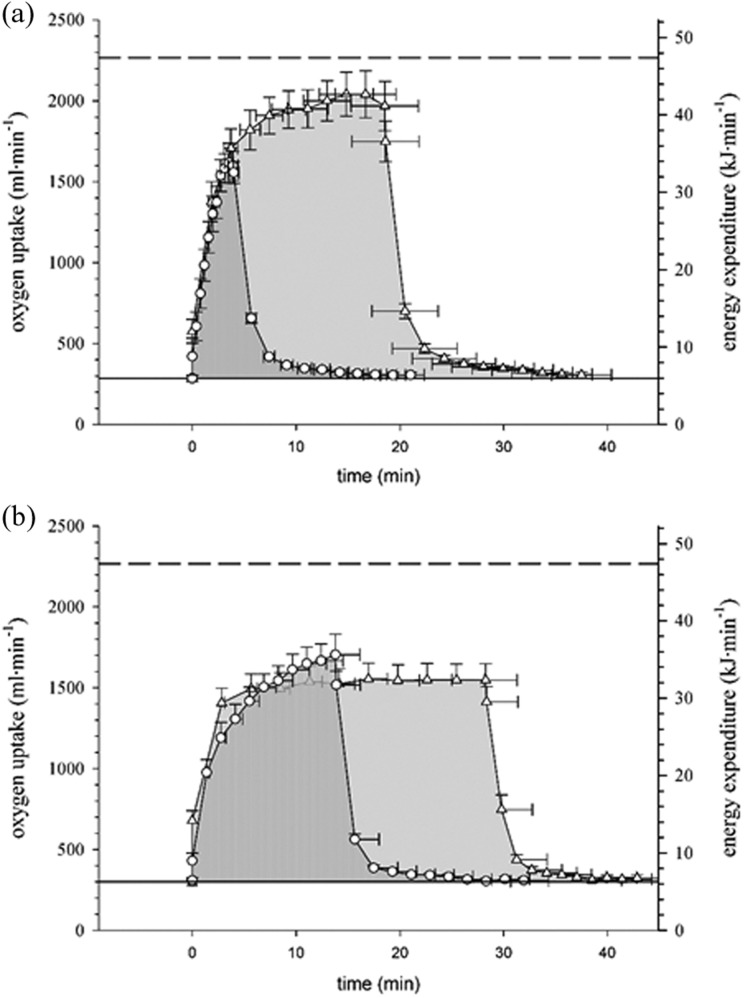

The protocol resulted in a linear increase in during ITM and ICE which enabled calculation of the power setting to achieve 80% and 60% for both cycling and walking (Figure 1). Participants endured treadmill walking at 80% and 60% for four and nearly three times as long, respectively, compared to cycling (Table 3) with similar cardiovascular responses. The pattern of EE during rest, exercise and recovery at matched intensities (Figure 4) was similar between modalities. A comparison of exercise, recovery and total EE between treadmill walking and cycling is summarized in Table 3. The total EE was four and almost three times greater for treadmill walking than cycling at matched metabolic intensity.

Table 3.

A comparison of the constant power endurance exercise parameters between treadmill walking and cycling at two matched intensities.

| High intensity 80% | Moderate intensity 60% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treadmill | Cycle | p value | Treadmill | Cycle | p value | |

| Duration (minute: second)a | 13:34 [08:07–28:05] | 03:23 [02:47–05:24] | 0.001 | 40:00 [20:34–40:00] | 13:23 [05:18–19:57] | 0.001 |

| End exercise: | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 136 [31] | 126 [21] | 0.14 | 124 [28] | 124 [28] | 0.99 |

| SpO2 (%) | 97 [2] | 98 [2] | 0.04 | 98 [1] | 98 [2] | 0.75 |

| BPsys (mmHg) | 151 [25] | 163 [23] | 0.08 | 139 [22] | 157 [23] | 0.01 |

| BPdia (mmHg) | 78 [11] | 82 [13] | 0.26 | 80 [11] | 77 [9] | 0.73 |

| BSa | 6.0 [4.0–9.0] | 7.0 [4.5–9.0] | 0.19 | 3.3 [1.9–6.5] | 4.5 [3.5–7.0] | 0.002 |

| LEa | 7.3 [4.0–9.0] | 7.0 [6.0–9.0] | 0.47 | 4.5 [3.5–7.0] | 7.3 [5.1–9.0] | 0.007 |

| Energy Expenditure: | ||||||

| Exercise (kJ) | 605 [428] | 79 [58] | <0.001 | 711 [413] | 323 [244] | 0.002 |

| Recovery (kJ) | 56 [34] | 41 [13] | 0.013 | 32 [14] | 34 [19] | 0.64 |

| Total (kJ) | 661 [421] | 120 [64] | <0.001 | 743 [418] | 357 [248] | 0.002 |

| Total (kcal) | 158 [101] | 29 [15] | <0.001 | 178 [100] | 85 [59] | 0.002 |

: peak oxygen uptake, EE: energy expenditure, HR: heart rate, SpO2: oxygen saturation, BP: blood pressure, BS: Borg Score Breathless Scale, LE: Borg Score Leg Effort. aMean [SD] unless which represents Median [interquartile range].

Figure 4.

A comparison of the energy expenditure between weight-unsupported (treadmill) and -supported (cycling) exercise in adults with obesity. Treadmill (triangles) and cycling (circles) at high (a) and moderate (b) intensity exercise. The shaded area under the curve represents total energy expenditure, that is, work, above rest including recovery. Dashed line --- represents VO2pk. : peak oxygen uptake.

Discussion

The optimal exercise prescription (the interactive effect of modality and intensity), to improve fitness and promote healthy weight loss, is unknown for adults with obesity. We measured EE and cardiovascular responses during two simulated exercise training sessions and noted that at a matched intensity the attainable total EE was greater during walking than cycling, for both vigorous (80% ) and moderate (60% ) intensities, as participants could sustain walking for considerably longer. As many individuals with obesity also have OSA, an independent cardiovascular risk factor, we chose to enrol participants in whom the potentially confounding effect of concomitant untreated OSA on exercise tolerance had been removed.

Our observations project that a thrice weekly treadmill exercise regimen would result in a greater EE of 388 and 277 kcal/week, at 80% and 60% , respectively, compared with cycling. The central cardiovascular stimuli were significantly higher for vigorous treadmill walking than cycling and similar between the two modalities for moderate intensity exercise. The total cost of walking, projected to about 500 kcal/week for both moderate and vigorous exercise, is a meaningful contribution to the recommended negative energy of approximately1000 kcal/week for healthy weight loss.35 These projections are an estimate for a long-term training programme and do not take into account any changes in the rate of EE over time relating to weight loss or exercise economy. The role of exercise should be placed within the context of the broader lifestyle intervention of calorie restriction and increased utilization to achieve weight loss but also improve cardiorespiratory fitness in this population.13 Despite similar reductions in body weight and fat, those who participate in caloric restriction plus regular exercise also improve insulin sensitivity, low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol and diastolic BP compared with those managed by caloric restriction alone.13 The mechanisms causing obesity are multifactorial and complex, and must be managed with more than a simplistic energy in minus energy out equals net energy balance, approach. However, there is still merit in ‘burning calories’ as effectively as possible for the reasons outlined and a negative energy balance is a factor which is easily understood and modifiable at an individual level.

To measure EE at comparable absolute cardiorespiratory intensities we matched the test intensity by oxygen uptake rather than by mode specific intensity of mechanical power or a physiological surrogate, for example, HR, for oxygen uptake. The former will be influenced by differences in movement economy between modalities. Whereas HR-based estimates of have been used to select speed and grade36,37 for the exercise prescription, this approach is not without error as HR can be increased during cycle compared to treadmill testing.24 We used a treadmill protocol21 which produced a linear increase in , similar to cycling, facilitating (Figure 2) the matched intensity which resulted in a similar pattern of response between modalities (Figure 3), such that total EE was determined by exercise tolerance. Although we had expected that the extra body weight, accelerating heavier arms and legs plus the effect of weight redistribution on gait, would limit walking tolerance,23,24 we observed that cycle exercise was less well tolerated and LE was significantly higher at the end of the shorter cycling sessions compared to walking in both tests. Whether this might be associated with local muscle fatigue compromising exercise tolerance remains to be explored.

Although the absolute aerobic capacity of this group was high, it was low relative to their body weight, with a of only 68% and 85% predicted in the ICE and ITM tests, respectively. Cardiovascular impairment (slope of the HR vs. and vs.) was not identified in any participants (Figure 2) but the HRpk was lower than predicted, suggesting peripheral deconditioning. This supports previous data which showed similar responses to maximal exercise testing between adults with obesity compared to obesity-related OSA.38 In the current study, the ICE was significantly less (<80%) than the ITM, a difference greater than reported (90–100%) among healthy groups21 but similar to the difference Porszasz reported (ICE 81% of ITM) using the same treadmill protocol among a group of healthy non-obese but sedentary participants.27 Importantly, we have uniquely identified the unappreciated substantial practical implication of this modality effect on endurance time at equivalent metabolic intensity.

is an indirect measure of EE and is more accurate when steady state is achieved which rarely occurs during vigorous exercise. In our participants, the increased until symptom limitation during vigorous intensity tests as well as during moderate intensity on the cycle (Figure 4). We assessed in recovery to account for the oxygen debt (the difference between the total in excess of the resting during the recovery period) in order to correct for EE not captured by exercise in the non-steady state. However, the kinetics were similar between modalities at matched intensities (Figure 4) and the relatively small inaccuracy in the estimation of EE would not account for the large differences in total EE reported.

As OSA is common in the population with obesity and often undiagnosed, we circumvented this potential confounder by recruiting patients with OSA successfully treated with CPAP. Our study did not include non-obese control participants as it was designed to inform the exercise prescription by comparing modalities at matched intensities, among participants with obesity. Nor did it include individuals with obesity but without OSA or those with untreated OSA. Although in the absence of specific cardiopulmonary limitations it is unlikely that individuals with obesity but without OSA would respond differently from our population, the generalization of our observations to other populations should be independently confirmed. In individuals with obesity and confirmed OSA, the latter is promptly managed but the concomitant lifestyle modifications designed to reduce cardiovascular risk are much less frequently addressed.39 As our study population was limited to participants with a BMI of mainly 30 to 40 kg m−2our observations may not directly extrapolate to Class III obese (BMI > 40 kg m2) individuals. We do note that the three participants with a BMI >40 kg m−2 had similar responses to the main group. Our observations may also not extrapolate to individuals with obesity and concomitant chronic respiratory disease, frequently referred for exercise training, in whom the ventilatory limitations to incremental exercise testing may be unaffected by the testing modality.40 We have focused on the desirable outcomes of EE and cardiovascular response from endurance exercise bouts, but other factors such as individual preference, comfort and risk of injury may impact on exercise adherence and therefore outcome of longer term training.

We acknowledge, that, by design, the vigorous test was always completed first as it was predictably the shorter test. The factor of interest, however, was ‘modality’ and its order was randomized. The two endurance tests were completed on the same day due to participant preference during the protocol development. Figure 4 shows that the EE had returned to baseline before the subsequent test. Although there was potential for these two factors to bias the results, the magnitude of the differences between the moderate and vigorous tests would suggest that the impact was minimal. We used a semi-recumbent position for the cycle ergometer to ensure that discomfort from an upright cycle was not the limiting factor. There are some reports that show that there may be a slightly lower compared to an upright cycle,41 but the differences are very small and could not account for the very large differences we have shown between the cycle and walking tolerability. We specifically chose to evaluate a matched metabolic intensity rather than a modality specific intensity to allow direct comparisons of the primary fitness stimulus. This led to the cycle tests being conducted at a very high intensity but demonstrated the modality/intensity relationship we wanted to investigate. Although typically exercise programs choose between 60% and 80% of the modality specific intensity as a surrogate for oxygen uptake, we can extrapolate that the cardiorespiratory stimulus would be lower during cycling compared to walking at an equivalent mode-specific intensity.

In summary, individuals with obesity and treated OSA tolerated treadmill walking at moderate to high intensities better than cycling resulting in greater EE, with increased or similar cardiorespiratory responses. This observation may inform their exercise prescription to contribute to a negative energy balance whilst stimulating cardiorespiratory fitness. Although current guidelines for obesity suggest the equivalence of modalities,19 the above observations would support walking as the preferred training modality for achieving the combination of weight loss and increased cardiorespiratory fitness.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: RAE contributed to the study conception and design, led the data collection, analysis and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. TED contributed to the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. PR contributed to data collection, interpretation of data and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. DB contributed to the study design, interpretation of data and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. RSG contributed to the study design, interpretation of data and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. Dr Goldstein is the guarantor of the article.

Author note: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article/paper/report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

References

- 1. World Health Organisation. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html# (accessed 30 October 2013).

- 2. Barlow CE, Kohl HW, III, Gibbons LW, et al. Physical fitness, mortality and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995; 19(Suppl 4): S41–S44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007; 116(9): 1081–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis JN, Hodges VA, Gillham MB. Physical activity compliance: differences between overweight/obese and normal-weight adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14(12): 2259–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. West SD, Kohler M, Nicoll DJ, et al. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on physical activity in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial. Sleep Med 2009; 10(9): 1056–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 2005; 365(9464): 1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet 2009; 373(9657): 82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Padwal RS, Pajewski NM, Allison DB, et al. Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ 2011; 183(14): E1059–E1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuk JL, Ardern CI, Church TS, et al. Edmonton Obesity Staging System: association with weight history and mortality risk. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2011; 36(4): 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iftikhar IH, Kline CE, Youngstedt SD. Effects of exercise training on sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Lung 2014; 192(1): 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188(8): e13–e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dobrosielski DA, Patil S, Schwartz AR, et al. Effects of exercise and weight loss in older adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015; 47(1): 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006; 114(1): 82–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larson-Meyer DE, Redman L, Heilbronn LK, et al. Caloric restriction with or without exercise: the fitness versus fatness debate. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010; 42(1): 152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller CT, Fraser SF, Levinger I, et al. The effects of exercise training in addition to energy restriction on functional capacities and body composition in obese adults during weight loss: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013; 8(11): e81692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shaw K, Gennat H, O’Rourke P, et al. Exercise for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4): CD003817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Papandreou C, Schiza SE, Bouloukaki I, et al. Effect of Mediterranean diet versus prudent diet combined with physical activity on OSAS: a randomised trial. Eur Respir J 2012; 39(6): 1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duncan GE, Anton SD, Sydeman SJ, et al. Prescribing exercise at varied levels of intensity and frequency: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165(20): 2362–2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009; 41(2): 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morton RH, Hodgson DJ. The relationship between power output and endurance: a brief review. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1996; 73(6): 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167(2): 211–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mattsson E, Larsson UE, Rossner S. Is walking for exercise too exhausting for obese women? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997; 21(5): 380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lafortuna CL, Agosti F, Galli R, et al. The energetic and cardiovascular response to treadmill walking and cycle ergometer exercise in obese women. Eur J Appl Physiol 2008; 103(6): 707–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(2): 319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones NL. Clinical exercise testing. 4th ed Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Services, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Porszasz J, Casaburi R, Somfay A, et al. A treadmill ramp protocol using simultaneous changes in speed and grade. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35(9): 1596–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evans RA, Dolmage TE, Robles PG, et al. Do field walking tests produce similar cardiopulmonary demands to an incremental treadmill test in obese individuals with treated obstructive sleep apnea? Chest 2014; 146: 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982; 14(5): 377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sue DY, Wasserman K, Moricca RB, et al. Metabolic acidosis during exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Use of the V-slope method for anaerobic threshold determination. Chest 1988; 94(5): 931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaesser GA, Brooks GA. Muscular efficiency during steady-rate exercise: effects of speed and work rate. J Appl Physiol 1975; 38(6): 1132–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gaesser GA, Brooks GA. Metabolic bases of excess post-exercise oxygen consumption: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1984; 16(1): 29–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O’Donnell DE, Travers J, Webb KA, et al. Reliability of ventilatory parameters during cycle ergometry in multicentre trials in COPD. Eur Respir J 2009; 34(4): 866–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Physical activity and health: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health andHuman Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NationalCenter for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1996. Available at: http://www.cdcgov/nccdphp/sgr/pdf/sgrfullpdf1996 (accessed 23 November 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freyschuss U, Melcher A. Exercise energy expenditure in extreme obesity: influence of ergometry type and weight loss. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1978; 38(8): 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lim JY, Tchai E, Jang SN. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise for obese patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. PM R 2010; 2(8): 723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rizzi CF, Cintra F, Mello-Fujita L, et al. Does obstructive sleep apnea impair the cardiopulmonary response to exercise? Sleep 2013; 36(4): 547–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Valero-Sanchez I, Wimpress S, Brough C, et al. Developing healthy lifestyle interventions for overweight patients with obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA): a survey of patient attitudes and current practice. Thorax 69: A67–A68. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ciavaglia CE, Guenette JA, Ora J, et al. Does exercise test modality influence dyspnoea perception in obese patients with COPD? Eur Respir J 2014; 43(6): 1621–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Quinn TJ, Smith SW, Vroman NB, et al. Physiologic responses of cardiac patients to supine, recumbent, and upright cycle ergometry. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995; 76(3): 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]