Abstract

Introduction. Endocarditis caused by yeasts is currently an emerging cause of infective endocarditis and, when accompanied byfever of unknown origin, is more severe since interferes with proper diagnosis and endocarditis treatment.

Case presentation. The Rio de Janeiro Infective Endocarditis Study Group reports a case of infectious endocarditis (IE) with negative blood cultures in a 45-year-old white female resident in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, previously submitted to kidney transplantation. After diagnosis and intervention, the valve culture revealed Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. The clinical aspects and overview of endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula spp. demonstrated that R. muscilaginosa have been isolated from the last IE cases from kidney transplanted patients.

Conclusion. Though most of the patients (in literature) recovered well from endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula spp., physicians must be aware for diagnosis of fungemia and fungal treatment in kidney transplanted patients suffering of fever of unknown origin in the modern immunosuppressive treatment.

Keywords: Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, infective endocarditis, immunocompromised, kidney transplantation

Abbreviations

CAIE, Community-Acquired infectious endocarditis; CAPES, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, from the Ministry of Culture/Brazil; CNPq, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, from the Ministry of Technology/Brazil; FAPERJ, Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro; FE, fungal endocarditis; FUO, fever of unknown origin; HAIE, Healthcare-Associated infectious endocarditis; HUPE, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital of State University of Rio de Janeiro; IE, infectious endocarditis; ITS, nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region; LILACS, Latin America Scientific Literature; MALDI-TOF, matrix assisted laser desorption-time of flight; MEDLINE, U.S. Library of Medicine; PubMed, WEB version of MEDLINE; SciELO, Scientific Electronic Library Online; UERJ, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro/State University of Rio de Janeiro.

Introduction

Fungal endocarditis (FE) is currently an emerging cause of infective endocarditis (IE). Although the most frequently fungal pathogens isolated from FE are Candida spp., there are other fungal agents including Aspergillus spp., and Histoplasma capsulatum [1–3]. Rhodotorula spp. is a basidiomycetous yeast, considered a member of the Cryptococcaceae family, and was previously described as a rare etiological agent in culture negative infective endocarditis [4, 5].

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection located in the endocardial valve(s), and according to the acquisition of organisms involved, is classified as Community-Acquired (CAIE) or Healthcare-Associated (HAIE). The estimated annual incidence of IE ranges from 3 to 9 per 100 000 in developed countries [6–8].

Even though the access to a microbiology laboratory and epidemiological data of IE in developing countries is scarce in medical literature, our group has shown that in Brazil, HAIE is more prevalent than CAIE in our cohort of cases in Rio de Janeiro. Our group has reported that Staphylococcus aureus was the most frequent (30 %) followed by Enterococcus faecalis (26.7 %) microorganisms isolated from positive blood cultures [9].

We hereby report a case of infective endocarditis due to Rhodotorula mucilaginosa in a kidney transplanted patient, who was admitted to our teaching hospital with fever of unknown origin (FUO). Thereafter an overview of cases of IE due to Rhodotorula spp. in English, Spanish and Portuguese literature since 1960 was done, and we have reported the 10th case.

Case report

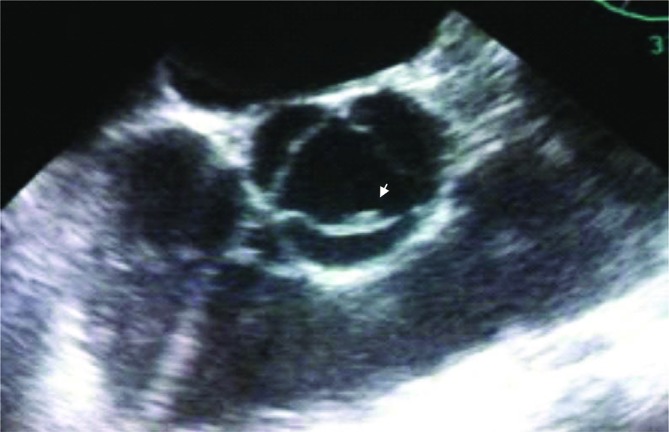

A 45-year old woman, with a history of deceased-donor kidney transplant in 2004, was admitted at HUPE in April 2012, for investigation of FUO. Three days after the admission, she developed daily peaks of fever varying from 38.0 to 39.3 °C, with intermittent fever pattern. Her complaints were fever and abdominal pain for 3 weeks prior to admission. She was under a combined imunossupressive therapy of Azathioprine, Sirolimus and Prednisone. Six peripheral blood culture sets were drawn on admission and incubated in BacT/Alert standard aerobic, after a 2 week investigation for the cause of FUO, all the blood culture sets were negative. In the beginning, the transthoracic echocardiography and radiologic studies were all inconclusive. After insisting on searching IE, a transesophageal echocardiography showed a heterogeneous mobile lesion adherent to the ventricular side of the aortic valve with 0.30 cm thickening and mild ventricular regurgitation (Fig. 1). Empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated with vancomycin and ciprofloxacin but failed to reduce the fever, which persisted for the following 2 weeks. The patient was then submitted to cardiac surgery, in which the aortic valve was found to be deformed by the vegetation. A fragment of the valve was sent to the microbiology laboratory for microbiological culture and DNA extraction for further search of micro-organisms involved in blood culture-negative organisms. After maceration of the valve in sterilised phosphate buffered saline, aliquots (10 µl) of the suspension were seeded into Thioglycollate Broth and in anaerobic supplemented blood agar base, and incubated in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37 °C. The Gram-stain of the suspension demonstrated yeast cells, and a 10 µl aliquot was also seeded in Sabouraud medium containing 10 mg ml−1 chloramphenicol, incubated at room (±23 °C) and 37 °C temperatures. The yeast grew in pure culture only after 72 h of incubation at room temperature. Sabouraud tubes also incubated at 37 °C demonstrated no growth. The yeast was plated in Blood Agar Base and incubated at room temperature for 72 h, and revealed dark-red colonies, with microscopic view of budding yeast cells, and positive reaction on Gram-staining (Gram-positive). The yeast was phenotypically characterised as Rhodotorulla spp. MALDI-TOF analysis identified the yeast as Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. PCR targeting the ITS region was performed and a fragment around 739 pb was observed. Sequences generated after automated sequencing presented 99 % homology with Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. The sequence was deposited at NCBI (KY113079). E-test (bioMérieux) showed susceptibility to amphotericin B (Amp B, 0.25 mg ml−1), voriconazole (0.50 mg ml−1) and flucytosine (5-FC, 0.19 mg ml−1). Two resistance profiles were observed for fluconazole (>256 mg ml−1) and for itraconazole (>32 mg ml−1). The patient was discharged after a 40 day therapy treatment with liposomal amphotericin B.

Fig. 1.

Infective endocarditis (IE) due to Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. A transesophageal echocardiogram showed a 0.3 cm thickening in the ventricular side of aortic valve (arrow).

Discussion

The prevalence of IE depends on the underlying heart disease, including structural congenital heart disease, rheumatic fever, degenerative heart disease, intravenous drug addiction, reconstructive cardiac surgery, pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillator, the prolonged use of intravenous catheters, immunocompromised and diabetic patients. The institutions have patients undergoing hemodialysis therapy and immunocompromised patients receiving cytostatic cancer chemotherapy have a higher prevalence of HAIE [6–10].

Rhodotorula spp. has been isolated from different sites including skin, nails, conjunctiva, as well as from respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [11, 12]. Although Rhodotorula spp. has a low prevalence in fungal endocarditis (FE), compared to Candida spp., Aspergillus spp. and Histoplasma capsulatum, the infective endocarditis team or internal medical physician should consider this fungus. Rhodotorula ssp. is a high risk for IE in a host with central venous catheter or immunosuppression [5, 11]. A search of MEDLINE, PubMed, Scielo and LILACS for endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula using the terms: ‘fungal endocarditis’, ‘fungus endocarditis’, ‘Endocarditis due to Rhodotorula’, ‘Infective Endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula’, in our overview, this case report is the 10th (Table 1) case of IE due to Rhodotorula since 1960 [1, 4, 13–19]. Amongst the genus, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa seems to be the most pathogenic species, and was responsible for 54.5 % cases of endocarditis, including in the last two described cases, occurring in kidney transplanted patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the case reports of infective endocarditis (IE) due to Rhodotorula spp. found in the literature (n=9).

| Year | Country/Reference | Age/Sex | Risk factors | Valve/type* | Species | Blood culture | Valve culture | Antifungal treatment† |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | USA/1 | 47/F | Mitral and aortic stenosis from rheumatic fever, dental procedure, indwelling catheter. | Ao/Native | ns | + | + | None | Deceased |

| 1962 | USA/13 | 56/M | Diabetes, rheumatic fever, prolonged urinary catheter, decubitus ulcer | ns | ns | + | np | Amp B | Recovered |

| 1969 | USA/14 | 39/M | Dental procedure, prolonged urinary catheter, decubitus ulcer | Mi/native | ns | + | np | Amp B | Recovered |

| 1975 | Israel/15 | 7/M | Recurrent tonsillitis, tonsillectomy | Mi/Ao/native | R. pilimanae | + | np | Flucy | Recovered |

| 2003 | Switzerland/16 | 53/M | Prosthetic valve, antibiotic use, endocarditis | Ao/Prosth. | R. mucilaginosa | – | + | Amp B+Itrac | Recovered |

| 2005 | Switzerland/17 | 56/M | Cardiac transplant recipient | Left Atrium appendice | R. glutinis | + | + | Lipos Amp B | Recovered |

| 2005 | Brazil/18 | 10/F | Central venous catheter | Right Atrium appendice | R. mucilaginosa | – | n.p. | Amp B+Flucy+Rifampicin | Recovered |

| 2011 | Brazil/19 | 58/M | Coronary stent | Ao/Native | R. mucilaginosa | np* | np | Amp B | Recovered |

| 2014 | USA/4 | 54/F | Diabetes, kidney transplant | Ao/Bioprosth. | R. mucilaginosa | + | + | Lipos AmpB | Recovered |

| 2017 | Brazil‡ | 45/F | Kidney transplant | Ao/Prosth. | R. mucilaginosa | – | + | Lipos AmpB | Recovered |

*Valve/Type: Mi, Mitral; Ao, Aortic; Prosth, Prosthetic; Bioprosth, Bioprosthetic; ns, Not specified; np, Not performed.

†Antifungal therapy: AmpB, Amphotericin B; Flucy, Flucytosine; Amp B+Itrac, Amphotericin B+Itracoconazole; Lipos AmpB, Liposomal Amphotericin B.

‡Case presented in this report.

Rhodotorula spp. has been reported in cases of fungemia, sepsis, meningitis, ventriculitis, peritonitis, keratitis, endophtalmitis, dacryocystitis, pneumonia, IE and more recently has been considered as an emerging pathogen [11, 12, 16–18]. The immunocompromised populations are at greatest risk of fungus infection. There are some reports of Rhodotorula infections in cancer patients with solid tumors, lymphoproliferative disease, HIV, diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure [5, 11]. In Rio de Janeiro, IE due to R. mucilaginosa was reported in a 45-year old kidney transplanted female patient where we found a vegetation of aortic valve even though blood cultures were negative. The frequency of Rhodotorula infections is reported in both genders since the first description in 1960, and with a mean of 41 years (Table 1).

In our overview, the left valve of the heart was more frequently implicated with Rhodotorula IE than the right valve. Among the nine patients previously reported in literature five of them involved aortic valve and only 30 % was related in solid organ transplant (Table 1). Rhodotorula infective endocarditis was reported associated with the widespread use of broad spectrum antibiotics and steroids in many chronic diseases [14]. Notwithstanding, it is possible that Rhodotorula spp. may be implicated with native valve, right sided heart infections and infective endocarditis in children and imumunocompetent patients [15, 19].

The yeast identification is ideal for the management of fungal endocarditis (FE) [3, 4]. The widespread prophylaxis and the empirical treatment of fungemia with triazole antifungal agents may also allow the emergence of specifically resistant fungi, including Rhodotorula species, due to its natural resistance to fluconazole and echinocandins [2, 5]. In the first report case of Rhodotorula IE, the patient died due to the absence of administration of anti-fungal treatment [1]. In our case, the patient was discharged after 40 days of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B and valve surgery.

One aspect that calls attention is the emergent isolation of R. mucilaginosa from patients accompanied after kidney transplantation, and in one patient after heart transplantation, R. glutinis was isolated (Table 1). When positivity of blood cultures is taken into consideration, four (36.7 %) case reports had negative blood cultures for infective endocarditis. Three cases according our overview occurred in Brazil and one in Switzerland (Table 1). Thus, Rhodotorula spp. can be involved in negative blood culture endocarditis, and the culture of the valve can provide the isolation of the microorganism, as recently stated [20]. Also, attention to incubation of culture media (at room temperature, ~25 °C) is also necessary for a proper growth and identification of R. mucilaginosa.

Rhodotorula spp. is an emerging opportunistic pathogen, particularly in immunocompromised patients. We need to improve medical microbiologic laboratory testing for fungemia diagnosis in renal transplantation population in the modern immunosuppressive treatment era.

Funding information

The authors received no specific grants from any funding agency.

Acknowledgements

This investigation was supported by Brazilian agencies: CAPES, FAPERJ, CNPq, and from the State University of Rio de Janeiro: SR-2/UERJ.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Ethical statement

The patient was informed and agreed with the report. Written informed consent was obtained, as required by the institutional committee: CAAE: 01247512.3.0000.5259.

References

- 1.Louria DB, Greenberg SM, Molander DW. Fungemia caused by certain nonpathogenic strains of the family Cryptococcaceae. Report of two cases due to Rhodotorula and Torulopsis glabrata. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:1281–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196012222632504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wirth F, Goldani LZ. Epidemiology of Rhodotorula: an emerging pathogen. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/465717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori S, Ferraris L, Orlando G, Tocalli L, Ricaboni D, et al. Fungal endocarditis observed over an 8-year period and a review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2014;178:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon MS, Somersan S, Singh HK, Hartman B, Wickes BL, et al. Endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:374–378. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01950-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuon FF, Costa SF. Rhodotorula infection. A systematic review of 128 cases from literature. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2008;25:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(08)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoen B, Duval X. Infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1425–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1206782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG, Tleyjeh IM, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland TL, Baddour LM, Bayer AS, Hoen B, Miro JM, et al. Infective endocarditis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16059. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.59. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damasco PV, Ramos JN, Correal JC, Potsch MV, Vieira VV, et al. Infective endocarditis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: a 5-year experience at two teaching hospitals. Infection. 2014;42:835–842. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomas JM, Martínez-Marcos FJ, Plata A, Ivanova R, Gálvez J, et al. Healthcare-associated infective endocarditis: an undesirable effect of healthcare universalization. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1683–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrocheilou-Paschou V, Prifti H, Kostis E, Papadimitriou C, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Rhodotorula septicemia: case report and minireview. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:100–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiliopoulou A, Anastassiou ED, Christofidou M. Rhodotorula fungemia of an intensive care unit patient and review of published cases. Mycopathologia. 2012;174:301–309. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shelburne PF, Carey RJ. Rhodotorula fungemia complicating staphylococcal endocarditis. JAMA. 1962;180:38–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050140040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leeber DA, Scher I. Rhodotorula fungemia presenting as "endotoxic" shock. Arch Intern Med. 1969;123:78–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1969.00300110080016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naveh Y, Friedman A, Merzbach D, Hashman N. Endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula successfully treated with 5-fluorocytosine. Br Heart J. 1975;37:101–104. doi: 10.1136/hrt.37.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeder M, Vogt PR, Schaer G, von Graevenitz A, Günthard HF. Aortic homograft endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. Infection. 2003;31:181–183. doi: 10.1007/s15010-002-3155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamma R, Carrel T, Schmidli J, Zimmerli S, Tanner H, et al. Transplantation of yeast-infected cardiac allografts: a report of 2 cases. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1159–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasqualotto GC, Copetti FA, Meneses CF, Machado AR, Brunetto AL. Infection by Rhodotorula sp. in children receiving treatment for malignant diseases. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:232–233. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000158970.27196.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loss SH, Antonio AC, Roehrig C, Castro PS, Maccari JG. Meningitis and infective endocarditis caused by Rhodotorula mucilaginosa in an immunocompetent patient. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2011;23:507–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandão TJ, Januario-da-Silva CA, Correia MG, Zappa M, Abrantes JA, et al. Histopathology of valves in infective endocarditis, diagnostic criteria and treatment considerations. Infection. 2017;45:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]